Making the Patient Opaque: Loss as Critical Methodology in the History of Medicine1

I want to start with three images from the history of tuberculosis; these three pictures are ones I regularly return to when writing, and are ones that help me articulate the kind of useful, ethical loss which I argue for today. They come from three different publications in a larger corpus of around 700 textbooks, journals, and government reports made between 1882 and 1926.

The first is an image of two doctors working in the Chicago Municipal Sanatorium’s pathology lab (fig. 1). Reproduced in the mid-1920’s in a public facing, monthly periodical, this picture displays the pathology lab, its contents, and the potentially candid action of two doctors at work.

Figure 1. Picture of the pathology lab of the Municipal Tuberculosis Sanatorium. In the foreground are wet tissue specimens presumably taken at autopsy from human patients. Found in Pinner, Max. “The Epidemiology of Tuberculosis” City of Chicago Municipal Tuberculosis Sanatarium Bulletin, 6(5). (1926). 9. Link to HathiTrust version.

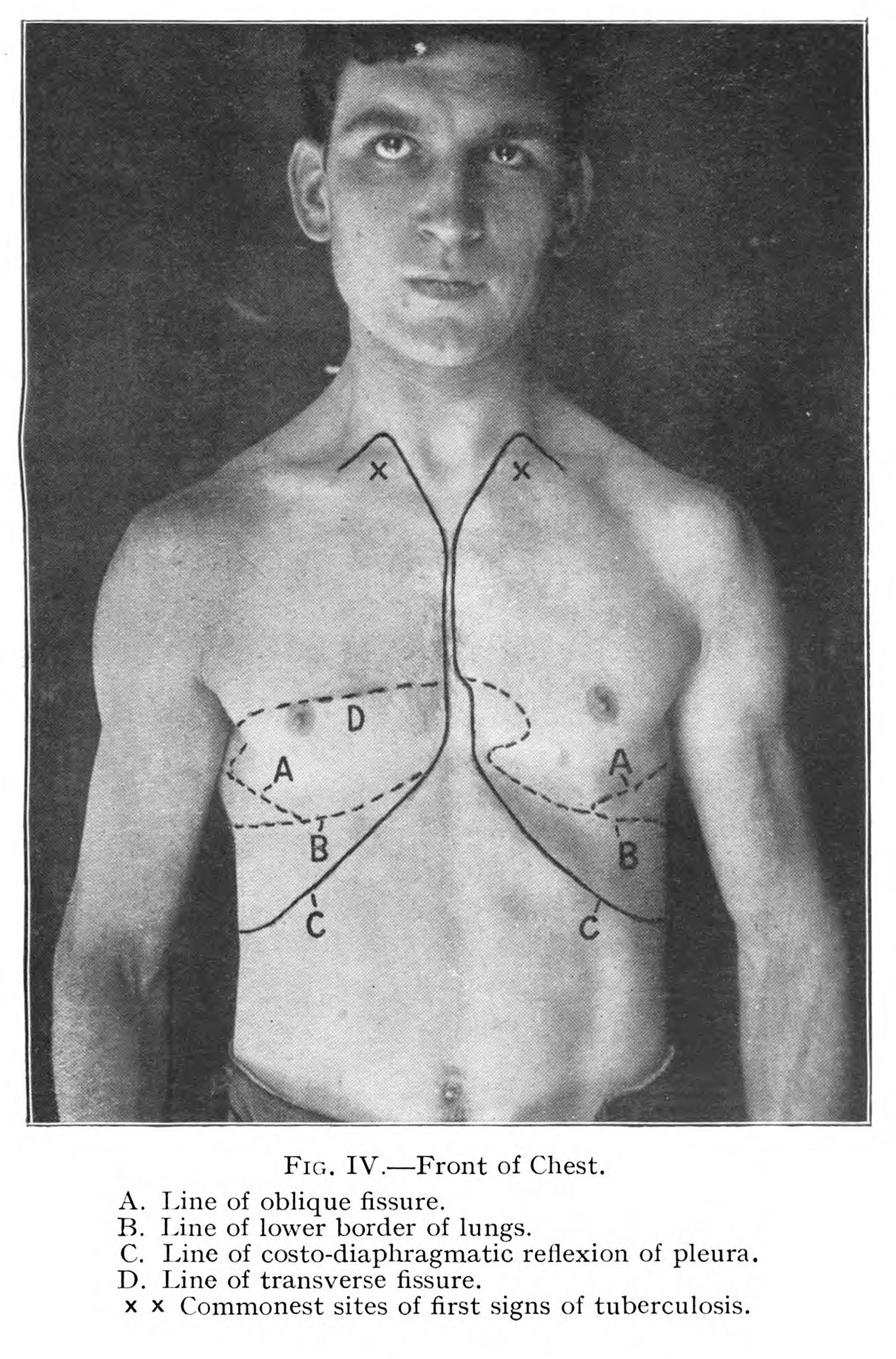

The second image is of a patient, photographed for use in W. M. Crofton’s Pulmonary Tuberculosis: Its Diagnosis, Prevention and Treatment (fig.2). Found in this short book for the aid of doctors, this image displays externally viewable symptoms of tuberculosis as it appears on the body of a male patient. The diagrams were added after the initial exposure.

Figure 2. A photograph of a man with tuberculosis with drawn material added to the image to aid in the diagnosis of the disease. Found in Crofton, W. M.. Pulmonary Tuberculosis: Its Diagnosis, Prevention and Treatment. (Philadelphia: P. Blakiston’s Son & Co., 1917), 16. Link to HathiTrust version.

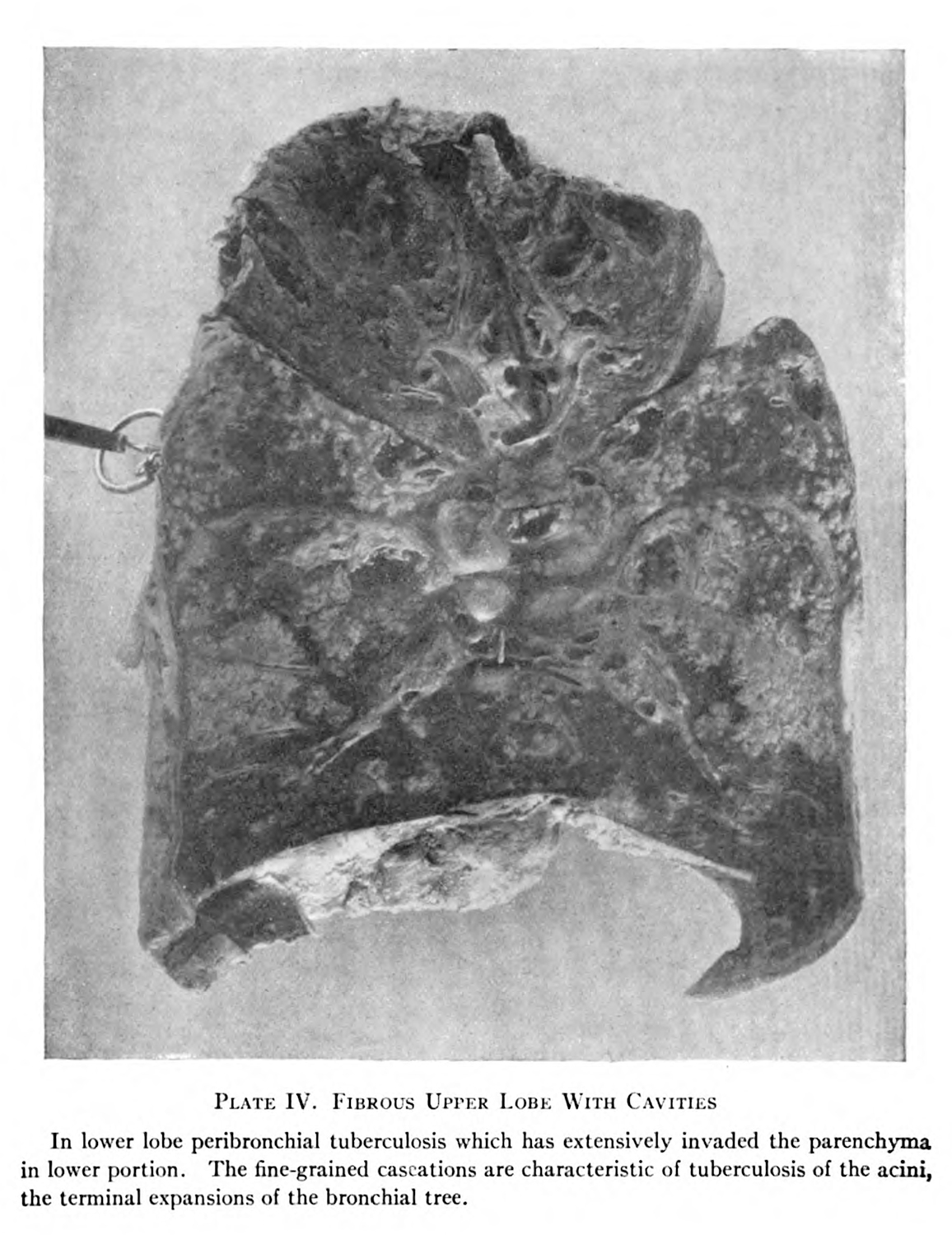

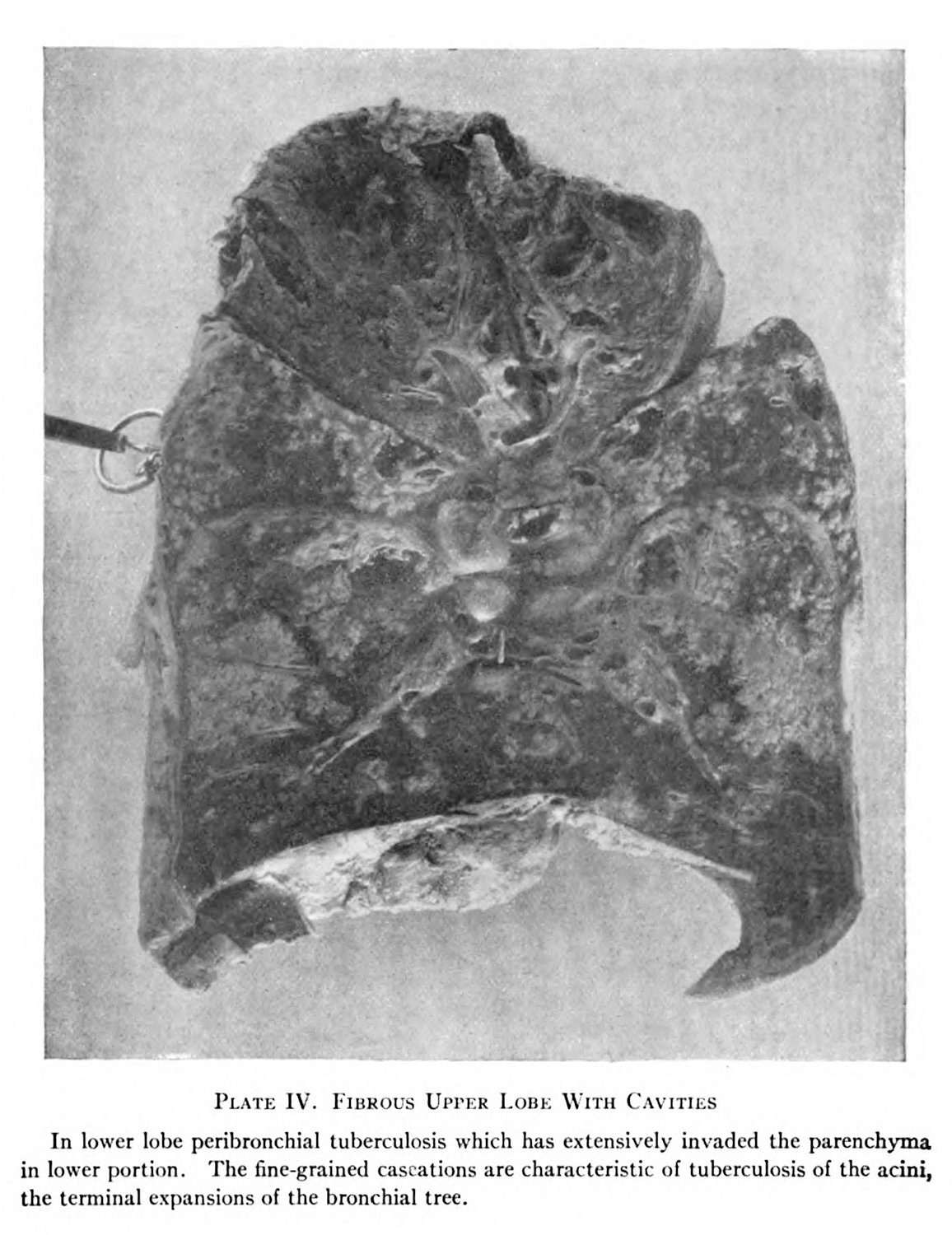

The final image is from a journal article by George E. Bushnell published in 1919 by the American Review of Tuberculosis (fig. 3). This photograph shows a wet specimen: the upper lobe of a patient who died of tuberculosis, and whose body was mined for useful material at autopsy. The intended audience, doctors trained in clinical vision, were supposed to be able to see the pathological difference between this organ and an idea natural or normal organ.2

Figure 3. A photograph of the upper lobe of a lung, extracted through the autopsy of an individual who died of tuberculosis. Found in Bushnell, George. “Manifest Pulmonary Tuberculosis” in The American Review of Tuberculosis 2(3). (1918), 170. Link to HathiTrust version.

These images have a few things in common: they are all photographs, they all relate to the scientific discourses around tuberculosis in the early twentieth century, and they all depend on an extractive relationship with the tuberculous patient.3 This hunk of viscera, expertly dissected and reproduced through photography was originally sourced from the body of a US army soldier who died under the care of the author—who was a doctor affiliated with the military at the time of publishing. The man photographed by Crofton is framed in such a way that his body is the focus, but his gaze seems to signal a disapproval or lack complete willingness to be framed.4 And finally, the two doctors who are working studiously in the lab are secondary to the jars of human viscera which have been prominently framed in the foreground. Each of these images, unique as they are, share a unifying thread: they rely on varying levels of extraction from and exploitation of human subjects, made made possible by the fuzzy, tenuously ethical standards of medicine in the period prior to the codification of informed consent.5

These images, and the thousands like them which populate my dissertation, The Tuberculosis Speicmen: The Dying Body and its Use in the War Against the “Great White Plague”, help me articulate and respond to an ethical crisis in the history of medicine: what is to be done with the troves of nonconseual, epistemically valuable material which represents an open wound for many communities.

Megan Rosenbloom, in her excellent book on anthropodermic bibliopegy, provides a helpful example to describe what I mean. In her history of books bound in human skin, she reflects on a book challenge directed toward Édouard Pernkoft’s Topographische Anatomie des Menschen (also known as Pernkopf’s Atlas). The challenge was centered around an issue of establishing consent: Pernkoft made the atlas as a doctor in Nazi Germany, and the subjects whose bodies were used for the illustrations may have been victims of the Nazi regime, and may have been anatomized without consent. Rosenbloom and her colleagues decided to keep the book, adding a detailed description to the book’s digital catalog entry. In her discussion of this decision Rosenbloom highlights a broader ethical crisis in medical libraries. She writes, “[t]hrough the challenge process, it became clear to me that if books have to be removed from a medical library because the bodies depicted in them were obtained through unethical and nonconsensual means, there might not be an anatomical text left on the shelf.”6

Rosenbloom’s comment gestures toward medical science’s history of malfeasance, from the racist anatomical exploitation of Saartjie Baartman,7 the pilfering of Indigenous remains in the American West by American anthropologists and racial scientists,8 the outsized use of black bodies in American anatomy labs,9 the classed violence expressed by national anatomy laws,10 as well as recent exposés by the Washington Post on the hundreds of human brains kept in the Smithsonian,11 handwringing at Philadlephia’s Mütter Museum regarding the display of remains with no record of consent,12 and the high profile arrest of Harvard morgue managers over the illegal sale of human remains.13 Issues of systemic racism, colonialist epistemics, and patient consent remain a huge problem for anyone interested in the history of medicine.

I myself am regularly dazzled by the astonishing spectacle of some of these images, and I usually choose the images which I suspect will get the most response from my audience. But there is a matryoshka-like problem here: as a scholar of medicine’s visual culture, I use images that were made from exploited subjects to make my arguments. Nested in this is a need to pick the most compelling, interesting images to make my point, and then doubly nested within both of these needs is the reality that as an academic I am trading on the reproduction of these images for my own professional benefit. Any argument aside, as much as I claim to be ethical, working toward a more just presentation of the past, I still depend on these awful materials for presenting on and publishing my work.

So what am I to do with these humans, who were photographed, who might have been dissected, and who are so nonchalantly depicted as objects in these photographs?

Leaving these issues for a moment, I want to explain how contemporary research norms circumvent these problems. I recently reached out to Indiana University’s (IU) institutional review board (IRB), detailing my work and double checking to see if I needed to apply for IRB approval. After a few quick emails, it was said to me that I did not need approval. While I do not have any writing from IU’s IRB itself, I can make an educated guess why this work does not qualify:

- the subjects that I study are most likely dead,

- the subjects I study are probably impossible to identify and thus any repercussions from me reproducing these images would be minimal for family members of the deceased, and

- the materials I use were produced in a period that is not covered by HIPPA.

My understanding may be wrong (I do not know exactly what the IRB’s qualifications for approval are), but the research protections codified by my home institution have little interest in the care of the long dead.

The problem is a two-fold one: first, these ethical questions minimize the felt repercussions against the already dead. The violations of anonymity, bodily autonomy, and personal beliefs are, at least under western cultural standards, not felt by the subject (they are dead after all). This way of thinking surmises that the dead cannot be harmed more, so it is not an ethical issue. My concern is that this disregards the diverse and meaningful postmortem practices and beliefs held by many communities, and it deflates the very real harm experienced by Indigenous groups regarding the care of their ancestors.14

The second problem goes hand in hand with the critiques of medical and anthropological collections by Indigenous scholars and activists: in many cases the act of creating specimens from human remains involved an anonymizing and objectifying process that decultured, dehistoricized, and dehumanized the subject from which they were drawn. Take the lung photographed for Bushnell (fig. 3): the upper lobe of the lung is foregrounded in such a way as to present an objectively neutral presentation of the object, and in the process the identifying information about the patient is lost.

This process is not necessarily the creation of a naturalistic, objective specimen, but is layered into covert practices that subvert accountability. Anonymity is not a concrete universal ethical standard: at the turn of the twentieth century anonymity was a method to deflect accountability, to hide illegally stolen remains in plain sight.15 Continued anonymization has dehistoriziced materials stolen from Indigenous bodies, and used in colonialist knowledge projects related to blood and DNA, and scholars like Kim TallBear and Joana Radin have worked to try to reconnect these remains to their original subject. TallBear argues that “[t]here are histories of politics that inhere in the [DNA] samples. Added to that are the politics imposed onto the samples by researchers who enforce subsequent requirements for the data”.16 TallBear stresses the historically entrenched research practices of genetic scientists to point to the social constructions which are made around scienfitic argument. “Native America DNA is material-semiotic” she writes. “It is supported by and threads back into the socio-historical fabric to (re)constitute the categories and narratives by which we order life.”17 Building on these Indigenous critiques, my own work stresses the material continuity between the dehistoricized, anonymized specimen and the human being from which it was extracted.18

I mention these issues because they point to why so much material has been retained: they are specimens not people, this logic argues; and even if these specimens were people, it would still be okay because our institutional ethics does not see any prolonged harm. From this, I want to ask a question: for museum professionals, historians of science, and others who work with stolen biomatter, what might your work look like if you stopped relying on the spectacular material stolen from human subjects?

To respond to this question, I want to meditate, briefly on loss. This conference is, after all, about losers and the power of loss, and what I want to stress is a multifaceted understanding of this loss. In the images shown today, there are a series of losses suffered by ailing subjects: loss of health, of life, loss of bodily autonomy (in life and after death), loss of organs; and we have the spectre of potential loss shared by the epistemic communities interested in health and its history. But what is lost if we extend some semblance of dignity back to the patients in the material?

My dissertation attempts to do this through the engagement with and literal application of Édouard Glissant’s notion of “opacity”. Glissant, an afro-Caribbean poet and philosopher, describes opacity in relation to Western knowledge practices that rely on complete understanding and control. The obsession with the root of a phenomenon, the desire to “grasp” (and thus enclose) a subject, brings with it a totalitarian relationship between the researcher and subject. Within these understandings, there is no essence that cannot be examined or understood, so long as it may be seen. Opacity, for which Glissant clamors, is an ethics of personal refusal: a way for the individual to resist the totality of Western knowledge systems by disallowing access and quantification.19

My work builds on Glissant’s to consider what happens if we extend opacity to research subjects of the past, and if we produce workflows that are sensitive toward the exploitation of subjects common to medicine prior to the establishment of informed consent? I have developed a dissertation platform that shows what an opaque history of medicine might look like. While it is nominally about tuberculosis, this digital intervention asks what is lost when parts of medical history are purposefully obfuscated so as to respect the patients from which knowledge was articulated?

The dissertation platform makes opacity literal in two ways and at three levels. The two functions are opacity filters for images and text: images will become more and more difficult to discern based on the filtering level, and there will be portions of text which are redacted in the argument as users increase the filtering. The three levels of opacity are marked as “non-opaque” “partial” and “opaque” and are defined as follows:

-

Non-opaque adds no filtering whatsoever to the images or text. It is just as I have written them.

-

Partial opaque applies opacity in such a way as to protect the privacy of the patient, but keeps the scientific information gleaned from the subject intact. This corresponds with contemporary norms regarding privacy.20

-

Finally, full opacity takes into consideration that the subject probably didn’t consent in the first place, and erases all index of the body (direct or indirect) from the material described, cited, or evoked in the argument.

Returning to the three photographs I started this paper with, what happens when I apply these levels of opacity to the image? What happens when I continue to flatten them, damage them, or erase potentially valuable data points? (For online viewers, this functionality is on this site!)

What I see is not so much loss in regards of their epistemic utility. What is lost in fact is a kind of enriching praxis. The process of making these images opaque, and the bespoke moments of erasure which comes with the use of Adobe Photoshop’s polygonal lasso tool, gives me time to meditate on the images themselves, to think of them singularly, and to reflect on the subject who was made to represent something about the disease. As the unnamed narrator of Chris Marker’s San Soleil argues, “[c]ensorship is not the mutilation of the show, it is the show. The code is the message. It points to the absolute by hiding it.”21 The final products, too, give me a way to frame out the object of the discourse and through this erasure see the implicit arguments in stark relief.

This argument, however, points to another useful problem, one which a contemporary critique of past research ethics helps point to: even with all of my handwringing, my careful intervention, I still rely on the bodies of others in my arguments. In challenging the necessity of these materials, my end goal is to think of processes where communities of knowledge workers can process the bulk of material in ways that prioritizes and respects the lives of the humans rather than seeing subjects as objects—as containing knowledge that just needs to be tapped, reaped, plundered, or extracted.

I am not asking for an entire erasure of the medical library, the medical museum, or the medical archive, but I am calling for a considered approach to divesting unethically sourced material precisely because these materials reproduce and reify the same epistemic practices that enabled the first abuse. Where, in the case of photographs, this approach may be moot, but in the cases of human remains my hope is to imagine ways of articulating these materials that call into question their very utility, that undermines the ways they produce popular spectacle and scientific argument. Rather than enshrine the very practices and people that turned those humans into objects, my hope is for a medical archive and museum that begins with the care for and attention to humans who lived and died.

Thank You.

-

I want to express some thanks to a few people who have assisted in the development of this project: specifically, I want to thank Kalani Craig, Michelle Dalmau, and Vanessa Elias at Indiana University’s Institute for Digital Arts and Humanities for their support on this project, and to IDAH more generally because the platform was developed in their summer incubator. Second, I want to thank both Xavier Danlies and Sagar Prabhu for their work on coding and data entry during the incubator. Most importantly, the code that I am sharing was developed by Sagar Prabhu, who deserves credit for making the functionality of this site possible. ↩

-

Foucault, Michel. The Birth of the Clinic: An Archeology of Medical Perception. Translated by A. M. Sheridan Smith. New York: Vintage Books, 1994; Curtis, Scott. “Photography and Medical Observation.” In The Educated Eye, edited by Nancy Anderson and Michael R. Dietrich, 68–93. Hanover: Dartmoth College Press, 2016; Gooday, Grame. “‘Nature’ in the Laboratory: Domestication and Discipline with the Microscope in Victorian Life Science.” The British Journal for the History of Science 24, no. 3 (1991): 307–41. ↩

-

See: Liboiron, Max. Pollution Is Colonialism. Durham & London: Duke University Press, 2021; Latour, Bruno, and Steve Woolgar. Laboratory Life: The Construction of Scientific Facts. 2nd ed. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1986. ↩

-

One of the major gaps in this work, which cannot be addressed in detail because of a limitation of the method, is an examination as to whether consent was given, and whether the patients had agency over their image being used. Rawling’s excellent work on photography in psychiatric wards notes a more contested field than the one I am describing here. Moreover, Susan Leder’s work on pre-Nuremberg Code medical ethics shows a much more messy patchwork of ethical practices than my broader critiques neatly afford.

Rawling, Katherine D. B. “‘She Sits All Day in the Attitude Depicted in the Photo’: Photography and the Psychiatric Patient in the Late Nineteenth Century.” Medical Humanities 43, no. 2 (2017): 99–110.

Lederer, Susan. Subjected to Science: Human Experimentation in America before the Second World War. Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995. ↩

-

Lederer, Susan. Subjected to Science. ↩

-

Rosenbloom, Megan. Dark Archives: A Librarian’s Investigation into the Science and History of Books Bound in Human Skin. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2020, 170. ↩

-

Mitchell, Robin. Vénus Noire: Black Women and Colonial Fantasies in Nineteenth-Century France. Athens: The University of Georgia Press, 2020. ↩

-

Redman, Samuel J. Bone Rooms: From Scientific Racism to Human Prehistory in Museums. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2016. ↩

-

Sappol, Michael. A Traffic of Dead Bodies: Anatomy and Embodied Social Identity in Nineteenth-Century America. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2002; Blakely, Robert L., and Judith M. Harrington, eds. Bones in the Basement: Postmortem Racism in Nineteenth-Century Medical Training. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1997; Warner, John Harley. “The Aesthetic Grounding Of Modern Medicine.” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 88, no. 1 (Spring 2014): 1–47. ↩

-

Richardson, Ruth. Death, Dissection and the Destitute. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1987. ↩

-

Dungca, Nicole, and Claire Healy. “Revealing the Smithsonian’s ‘Racial Brain Collection.’” The Washington Post, August 14, 2023. https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/interactive/2023/smithsonian-brains-collection-racial-history-repatriation/. ↩

-

Judkis, Maura. “A Museum’s Historic Remains Are Now the Center of an Ethics Clash: At the Mütter Museum in Philadelphia, 19-Century Body Parts Are Reexamined under the Modern Lens of Medical Consent.” The Washington Post, July 27, 2023. https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/2023/07/26/mutter-museum-controversy-philadelphia/. ↩

-

Lawrence, Janelle. “Harvard Medical Morgue Chief Charged with Selling Body Parts.” Time, June 15, 2023. https://time.com/6287536/harvard-medical-morgue-chief-charged-selling-body-parts/. ↩

-

In the more than thirty years since the passing of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act there is still reticence in returning remains. See: Jaffe, Logan, Mary Hudetz, Ash Ngu, Pro Publica, Graham Lee Brewer, and NBC News. “America’s Biggest Museums Fail to Return Native American Human Remains.” Pro Publica, January 11, 2023. https://www.propublica.org/article/repatriation-nagpra-museums-human-remains. ↩

-

See: Bones in the Basement; Sappol. ↩

-

TallBear, Kim. Native American DNA: Tribal Belonging and the False Promise of Genetic Science. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013, 7. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

I mention “material continuity” to point toward a way that new materialism (often a method to deflect from indentity-based critiques) may be leveraged to examine sublimated processes in colonial practices. See: Nooney, Laine. “A Pedestal, A Table, A Love Letter: Archaeologies of Gender in Videogame History.” Game Studies 13, no. 2 (2013); Adema, Janneke, and Gary Hall. “Posthumanities: The Dark Side of ‘the Dark Side of the Digital.’” Journal of Electronic Publishing 19, no. 2 (2016). https://doi.org/10.3998/3336451.0019.20; Islam, Md. Monirul. “Posthumanism: Through the Postcolonial Lens.” edited by Debashish Banerji and Makarand R. Paranjape, 115–29. Springer India, 2016.

I also have begun thinking about this way in connecting material histories to colonial death cultures. See: Purcell, Sean. “Rendering in Analog Games: Dissected Puzzles and Georgian Death Culture.” Game Studies 23, no. 1 (2023). ↩

-

Glissant, Édouard. Poetics of Relation. Translated by Betsy Wing. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1997. ↩

-

See: Johns, Martin K. “Informed Consent for Clinical Photography.” Journal of Audiovisual Media in Medicine 25, no. 2 (2002): 59–63; Berle, Ian. “The Ethical Context of Clinical Photography.” Journal of Audiovisual Media in Medicine 25, no. 3 (2002): 106–9. ↩

-

Chris Marker. Sans Soleil, 1984. ↩