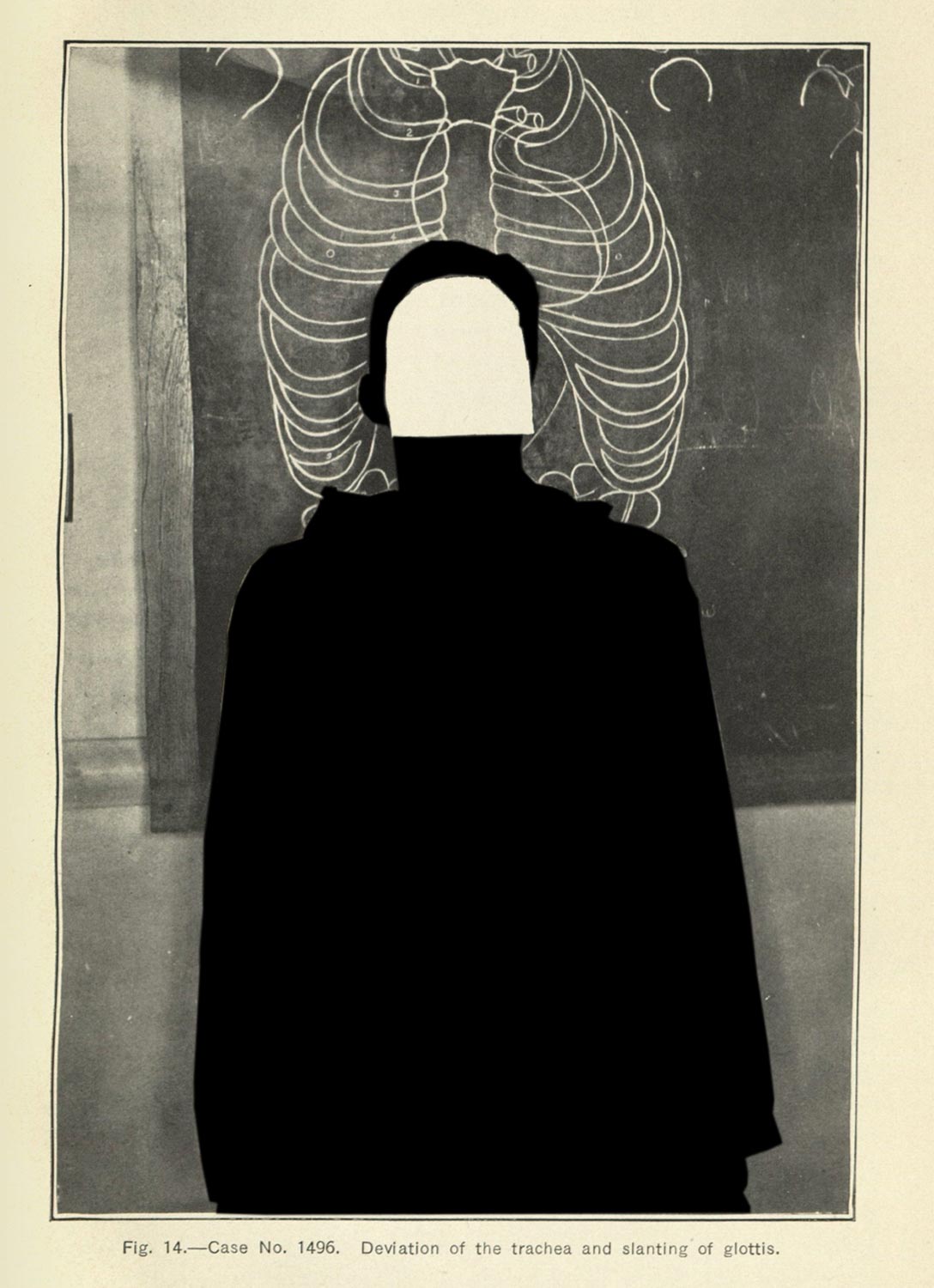

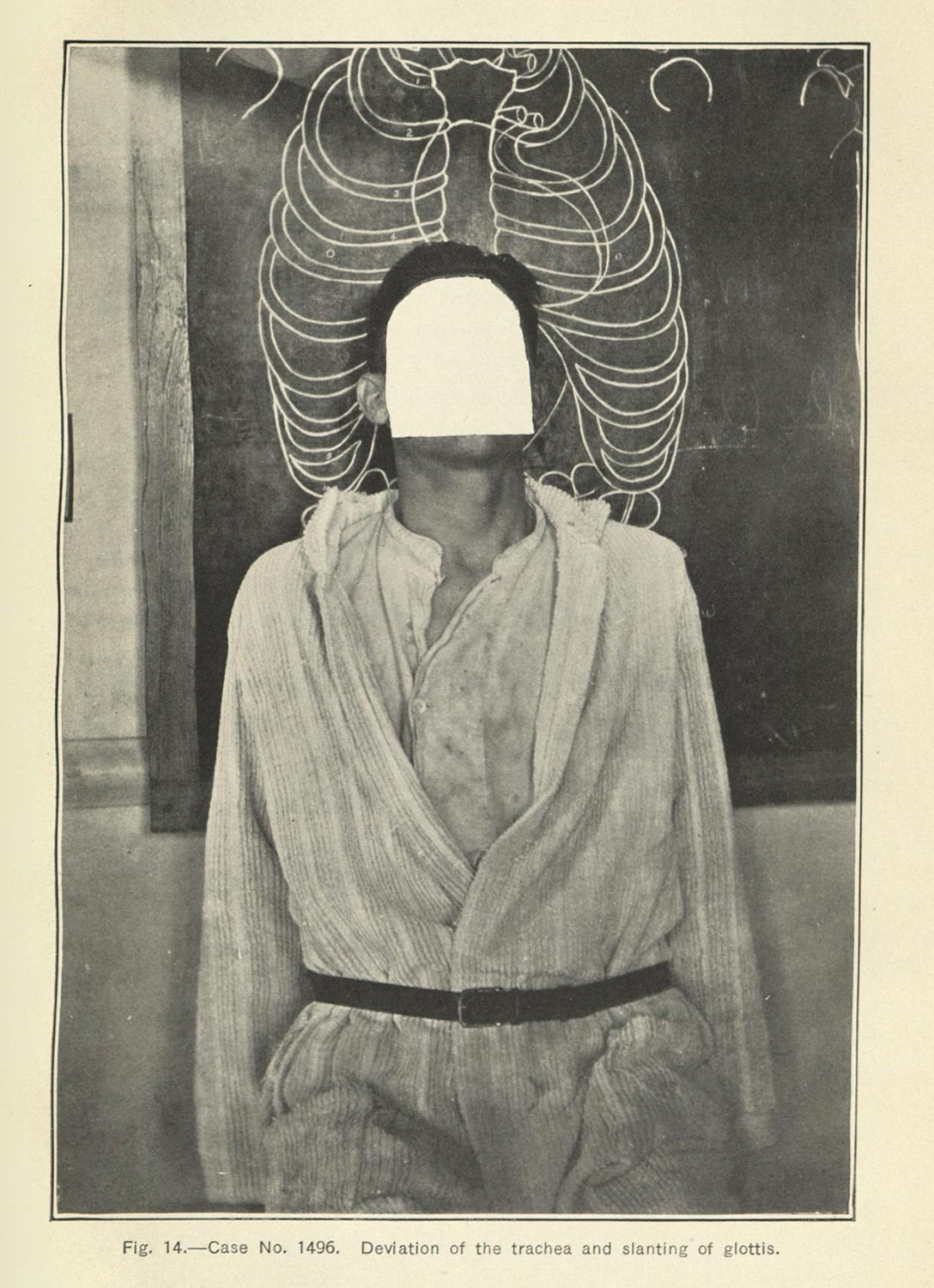

From Nathan Barlow and James C. Thompson. Small Pneumothorax in Tuberculosis. (Washington: Government Printing Press, 1922).

Introduction

Today, I want to share some of the work that I have been doing at the New York Academy of Medicine’s library. Specifically I want to share some notes on the visual culture surrounding tuberculosis at the turn of the twentieth century. My goals for this talk are relatively simple: I want to use tuberculosis to think about how medical researchers saw their patients and saw the disease, and I want to use this framework to address a methodological issue which is central to my work.

I am going to break this discussion into three parts: first (recognizing that the audience today comes from a range of disciplines) I want to outline visual culture, and talk about how it is discussed in the history of medicine. From this framework I want to look at a subgenre of images—what I’m defining as pathological portraiture—to help nuance some understandings about the ways doctors represented their patients in scientific research. Finally, I want to reflect on these images, and describe how these materials have changed my own design and arts practices, offering some provocations for future scholarship in the history of medicine.

Visual Culture

Before I go too far into the history around tuberculosis, I want to briefly touch on the concept of visual culture. While indebted to the work of Michel Foucault and his critiques of modern medicine, visual culture has been most prominently adopted by scholars working in film studies and art history starting in the eighties and nineties.Mirzoeff, Nicholas. An Introduction to Visual Culture. London & New York: Routledge, 2000. During this period visual culture scholars became interested in the ways human subjects were taught to see, how this vision produced understandings of the world, and how these visual practices were undergirded by ideological power structures. Jonathan Crary succinctly articulates this framework, writing: “[v]ision and its effects are always inseparable from the possibilities of an observing subject who is both the historical product and the site of certain practices, techniques, institutions, and procedures of subjectification.” Crary, Jonathan. Techniques of the Observer: On Vision and Modernity in the Nineteenth Century. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1992. 5.

Interdisciplinary by design, visual culture scholars were interested in pulling from multiple discourses to make their claims, often looking beyond prescribed hierarchies of high and low taste to instead describe a broader view of how visual artifacts were made and interpreted. There are plenty of discussions of medicine’s visual culture, and I will be drawing from Catherine Waldby’s The Virtual Human Project, Jose van Djick’s The Transparent Body, and Lisa Cartwright’s Screening the Body at different points in this essay. And these books are exceptional works of scholarship in their own right, but they share a two minor methodological problems: first, they tend to take culture to represent a certain scale of human interactions built as it is by ideology, law, and discourse, meaning that the interconnected conversations, interventions, and contestations get blurred into an overarching conception of the culture; and two, they tend to rely on more specific case studies to represent larger trends in that deeply contextual and fraught cultural space. This is not necessarily a bad thing (I am going to do the same in this talk today), but it means that some conceptions that we scholars may believe to be true to a larger field (like, say, western medicine) may be more tacky than smooth.

This problem is especially prominent in the ways the notion of the clinical gaze is articulated in visual culture analyses of medicine. The clinical gaze, according to Michel Foucault, is a visual practice where the doctors are trained to see disease as it is represented on the patient’s body. Formed through a contrast between what is seen on the surface of the patient’s body and an idealized ‘normal’ conception of human anatomy, the clinical gaze looks past any individual subject and sees only the physiognomy of disease.1 This framework has helped many scholars articulate how alienating and dehumanizing western health systems are for so many patients, and have noted how the obsession with a supposedly ‘normal’ anatomy presupposes the centrality of an able-bodied, white, heterosexual, cis-male body. Erin O’Connor has productively tied this ocular practice to the use of photography in medicine, arguing that the technology’s reproductive affordances enabled doctors to become familiar with all sorts of rare pathologies, further enshrining the same focus on the aberrant symptoms in diagnosis.2

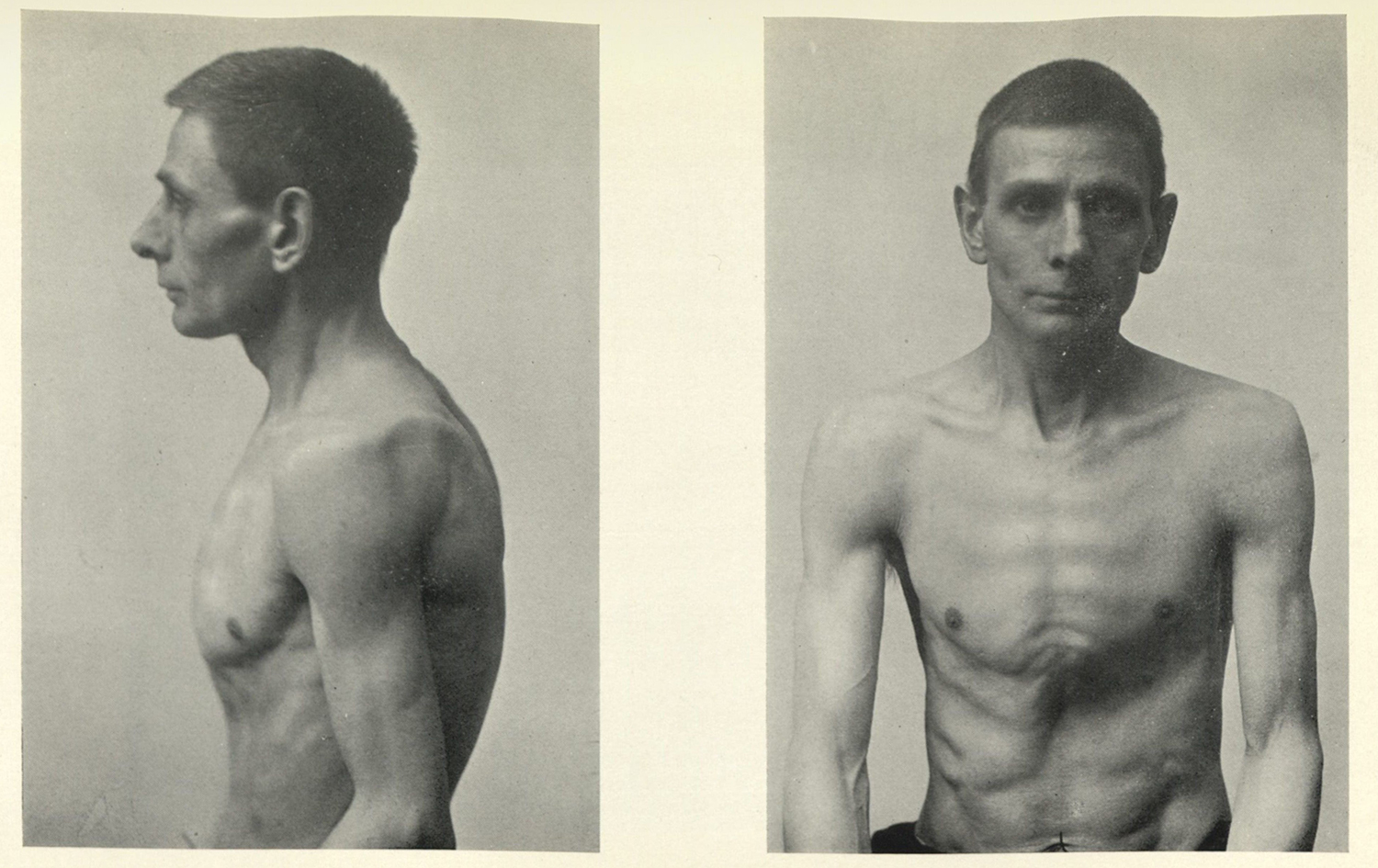

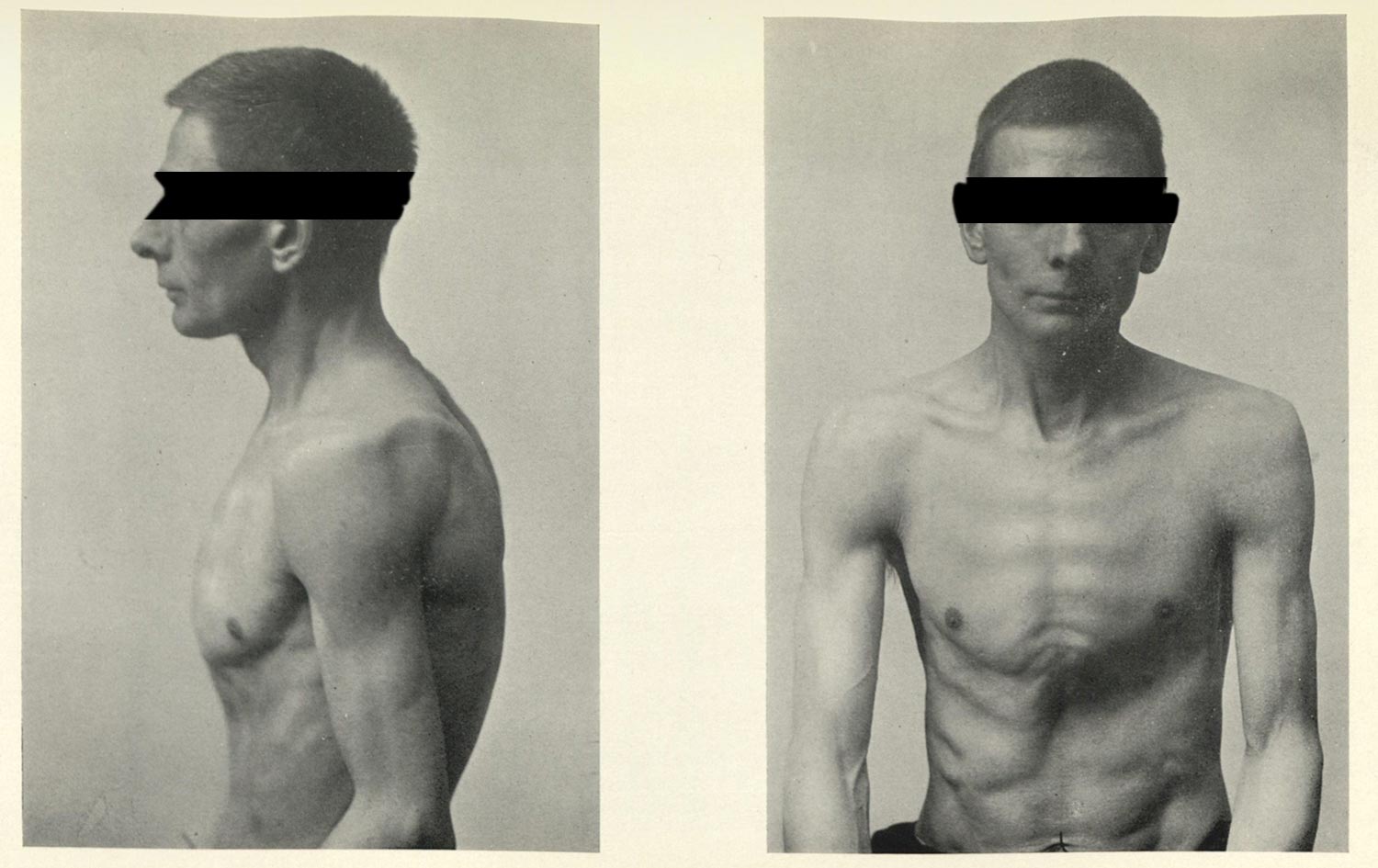

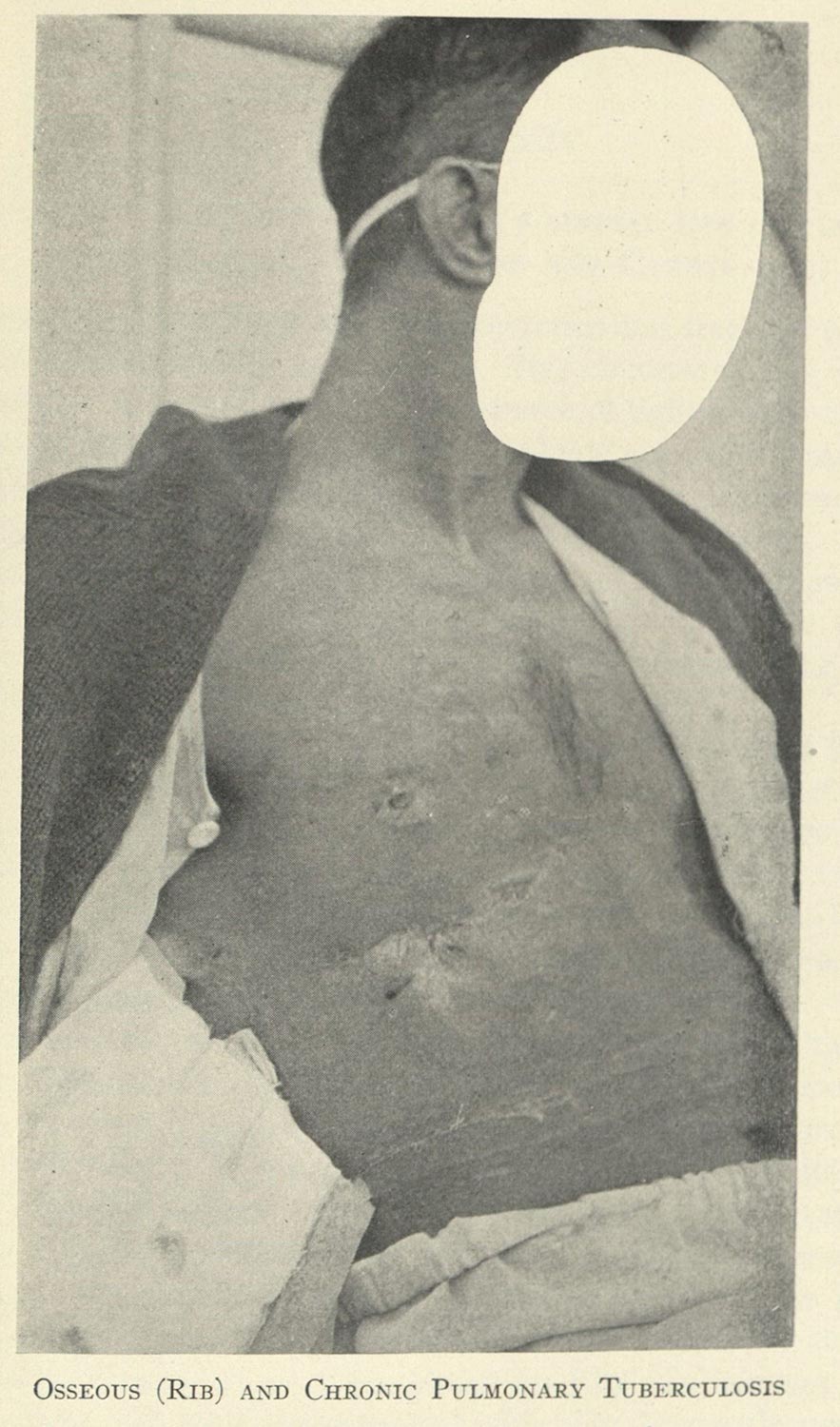

To more concretely explain how this practice works, I want to turn to an image found in a book by John Guy (fig. 1). As someone who is not professionally trained in clinical vision, I may consider this photograph’s main focus or subject to be the man. I may be drawn to reflect on his expression, to consider his class, and so on; however, if I look at this image within the framework of the clinical gaze, I am instead supposed to look beyond the individual and look directly at the symptom: the man’s asymmetrical chest. Any of the other material is unimportant because this image conveys an argument about the relationship between a symptom and the effects of tuberculous infection.

Figure 1. John Guy. Pulmonary Tuberculosis: Its Diagnosis and Treatment: A Handbook for Students and General Practitioners. 1923.

Foucault’s broad critique of medical vision is in many cases spot on, and it helps me as a scholar better understand how a discipline with a philosophy to “do no harm” can have such a storied history of malfeasance. The problem is less Foucault’s conclusions, so much as an issue in method: thinking about medicine in general flattens and distorts the specific.

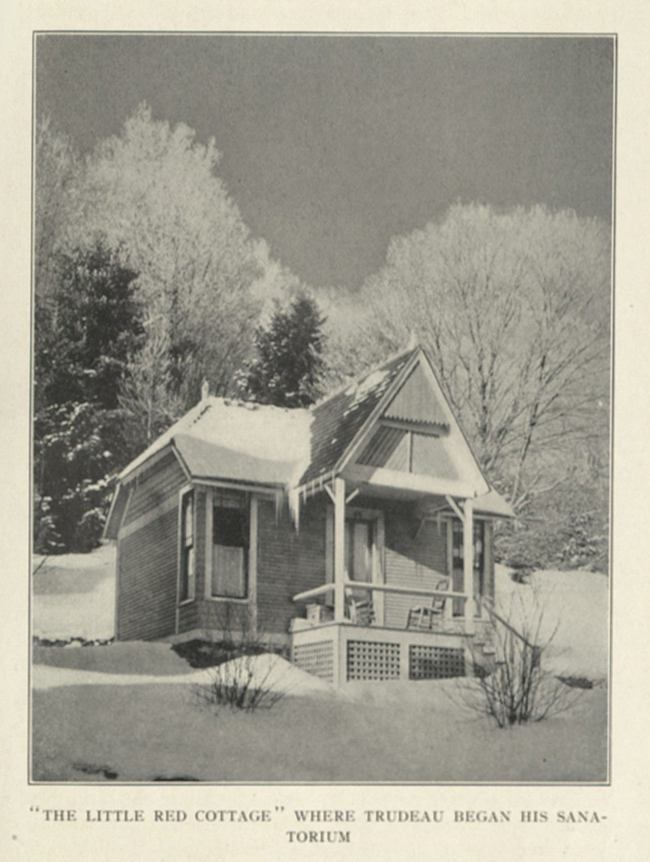

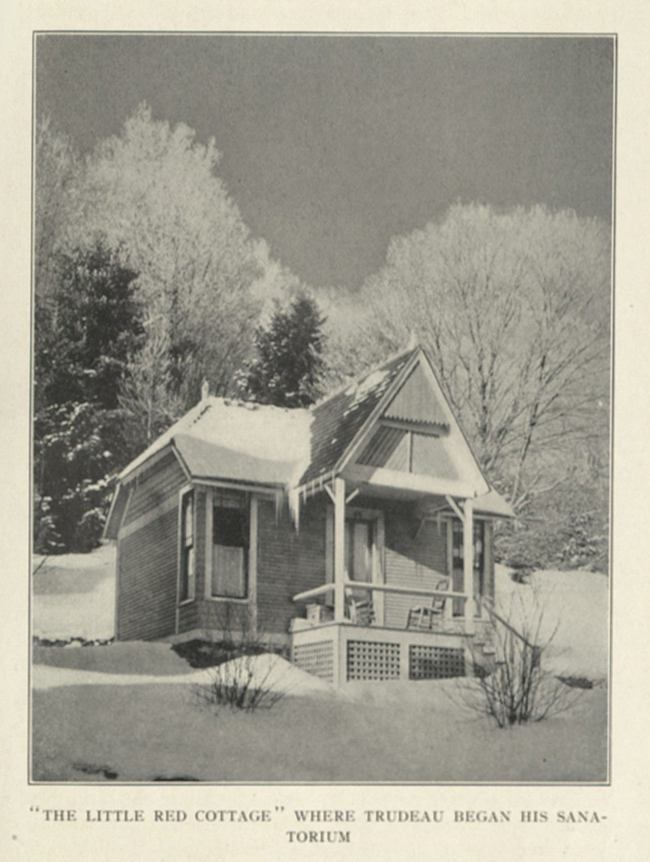

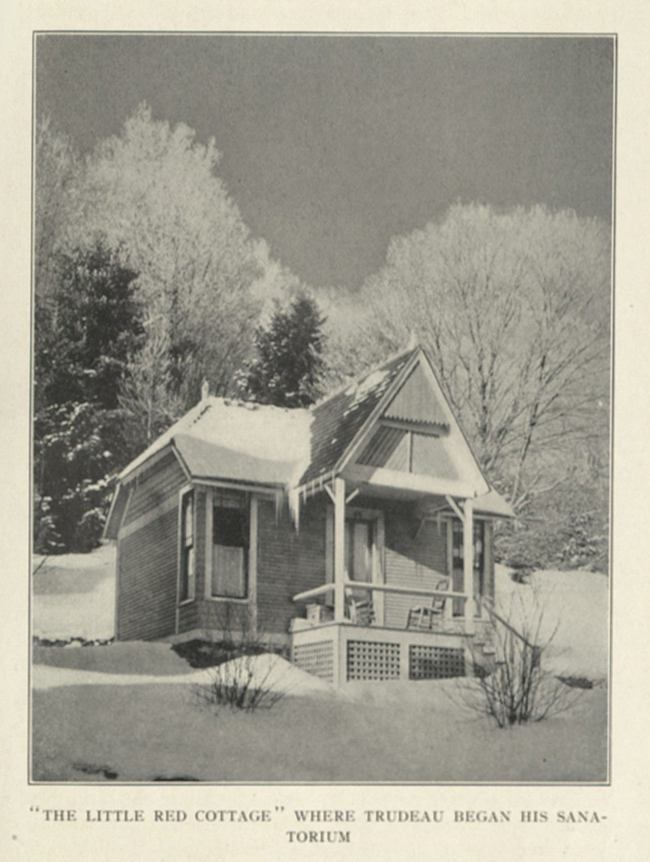

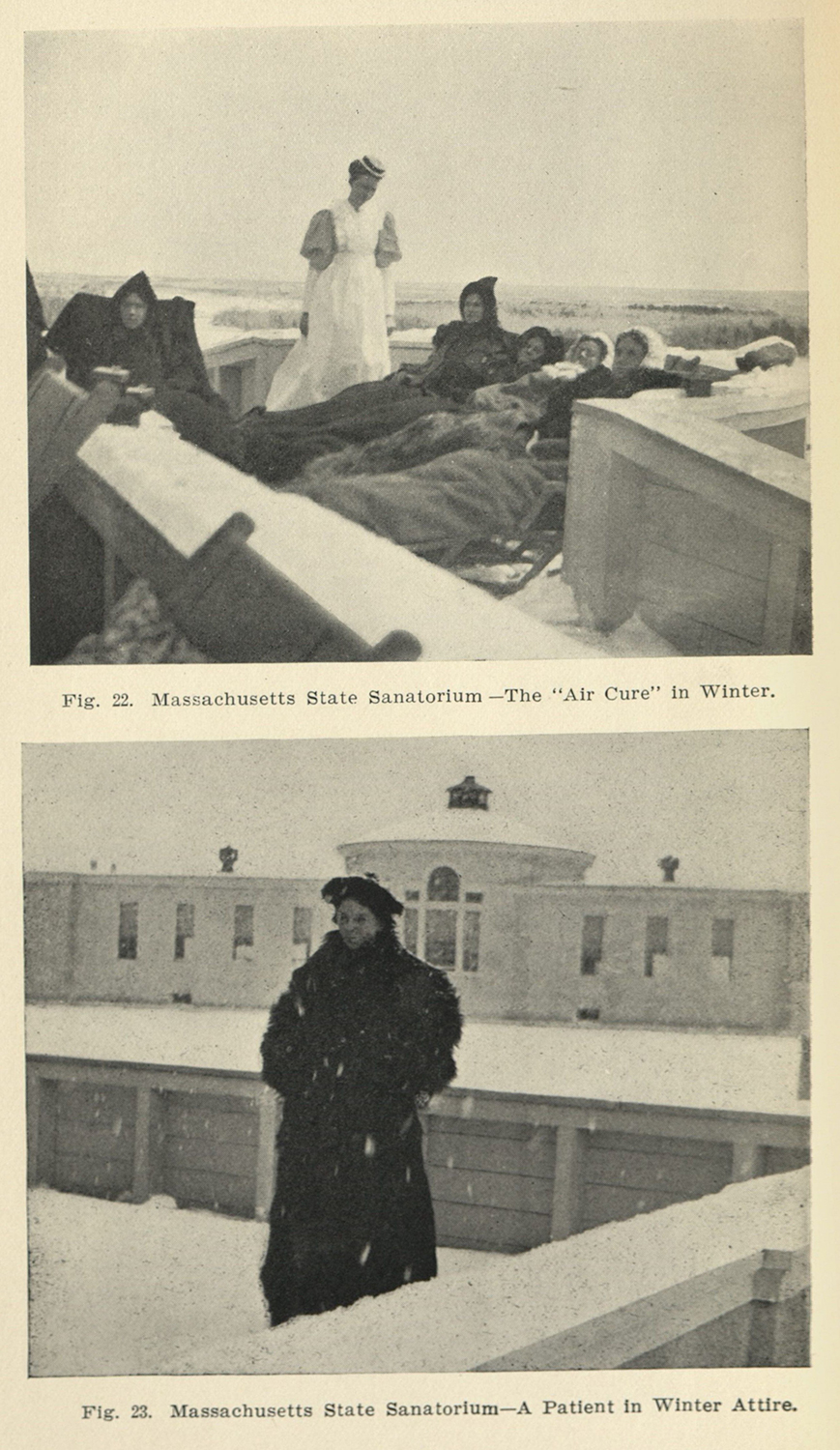

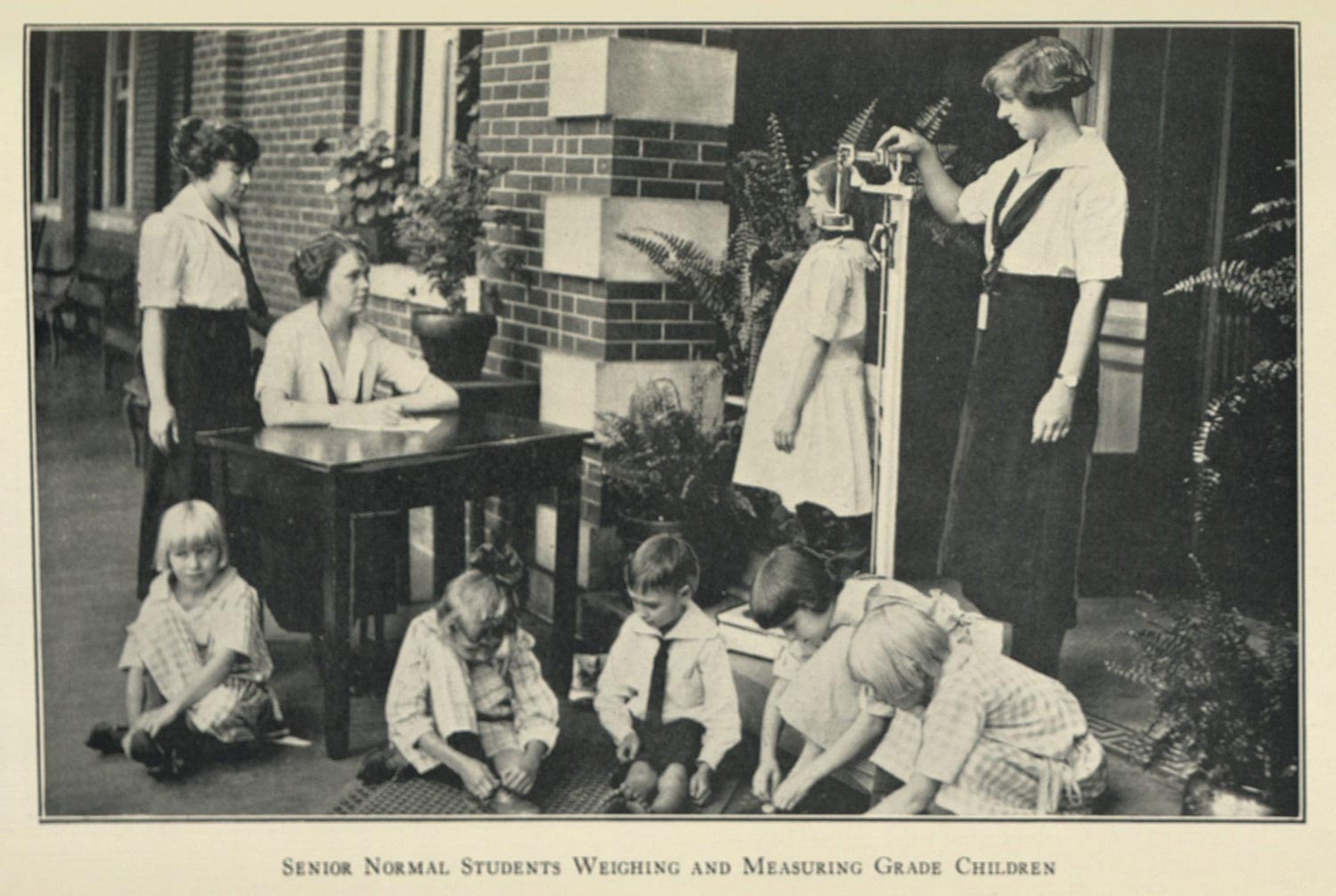

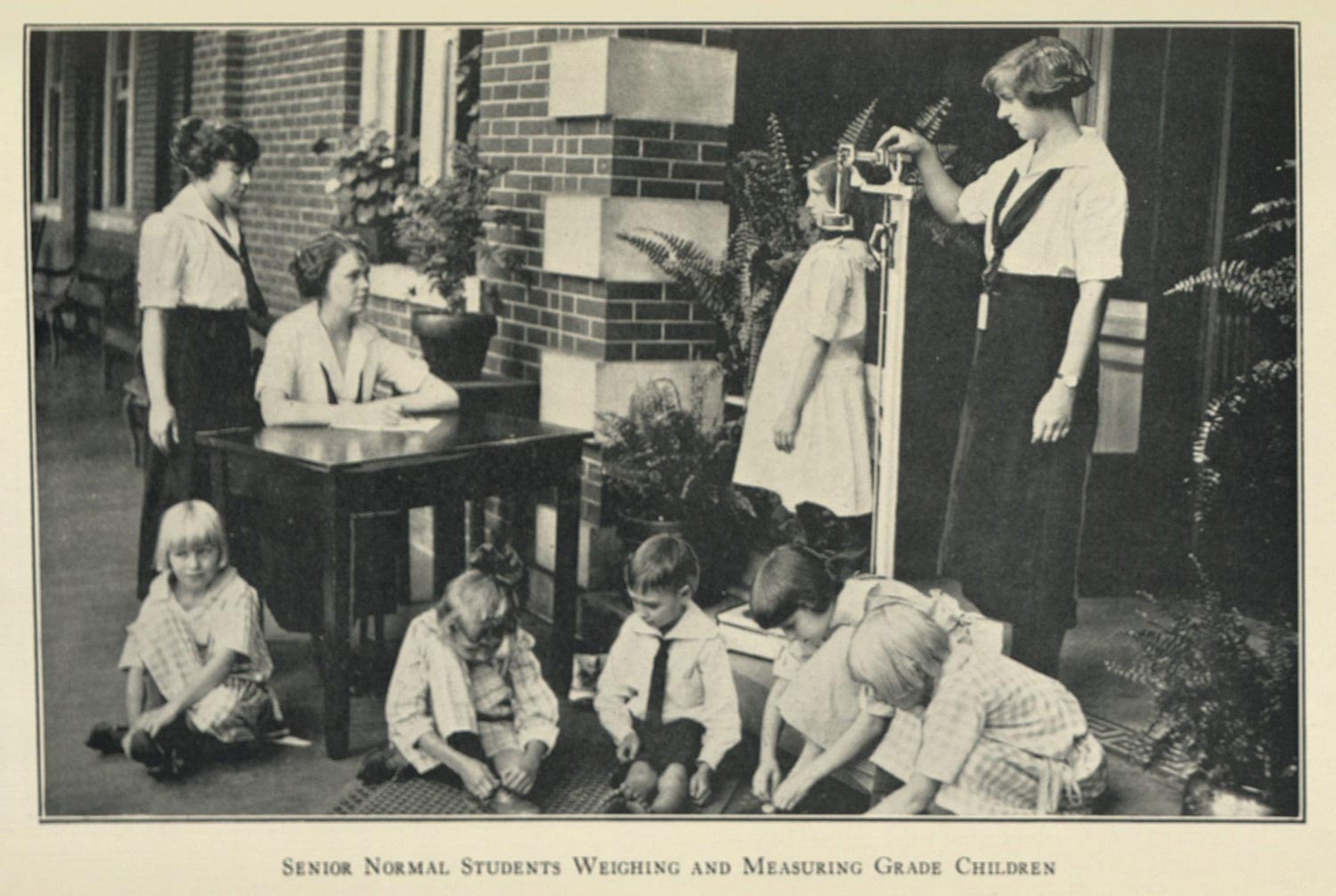

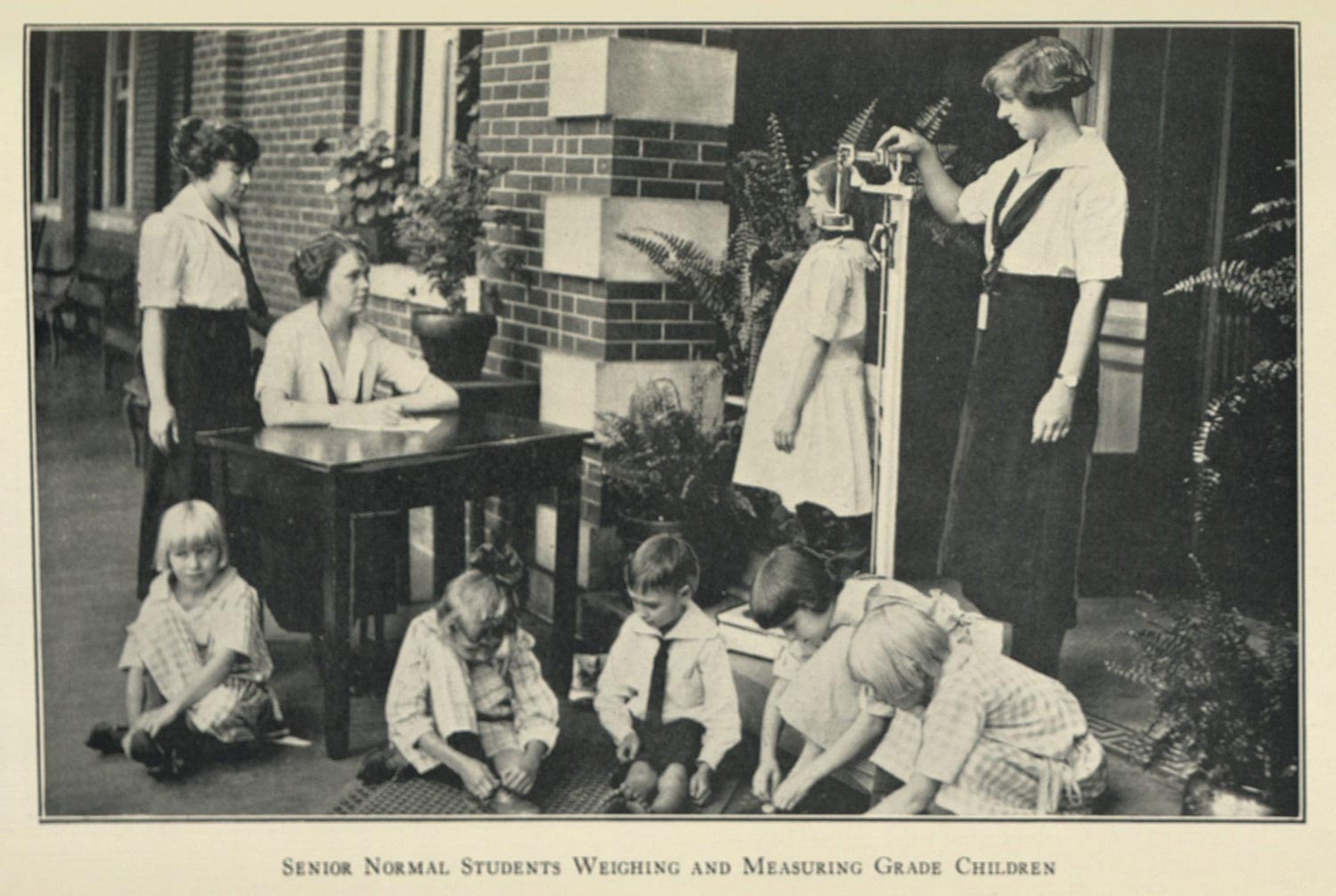

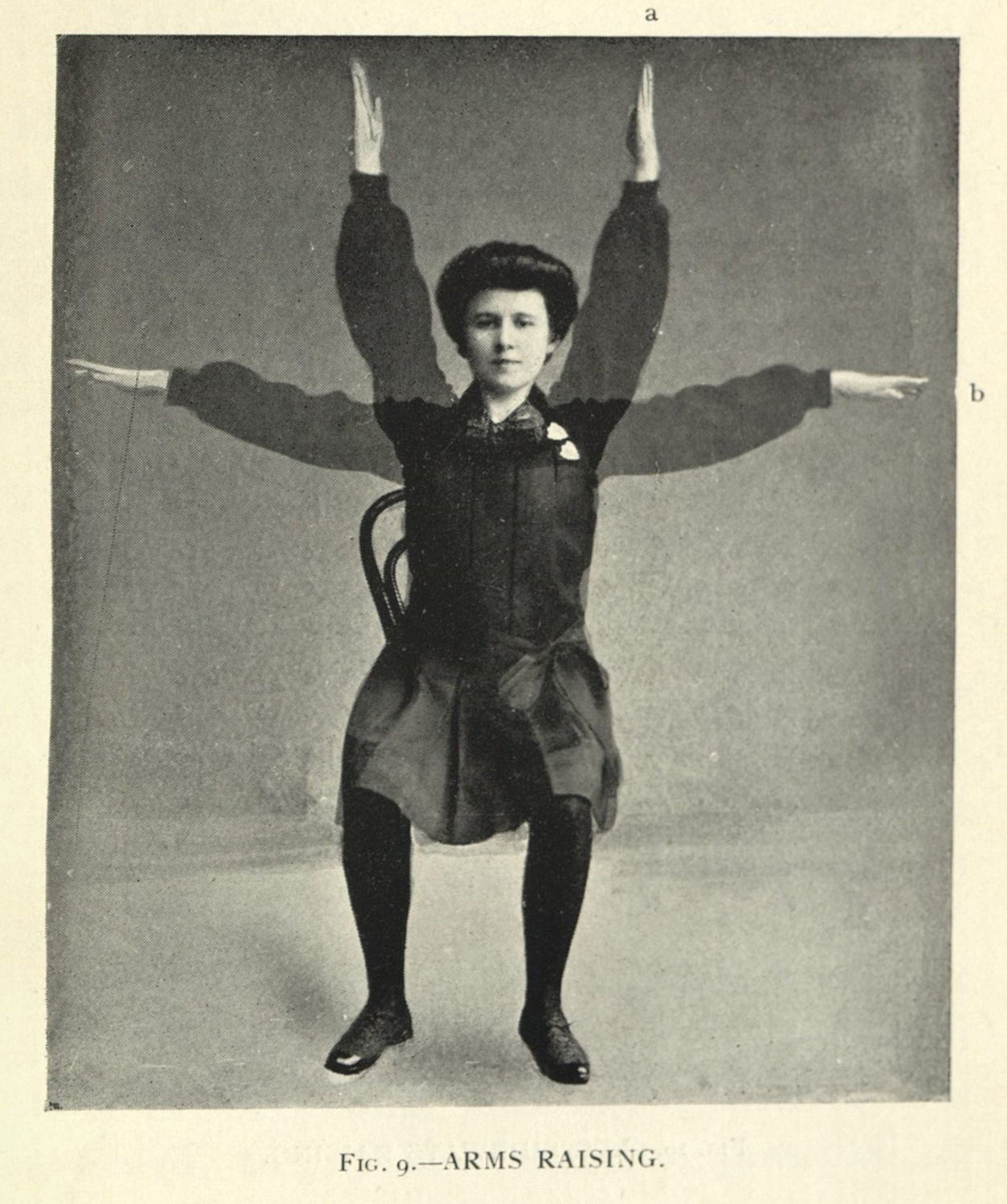

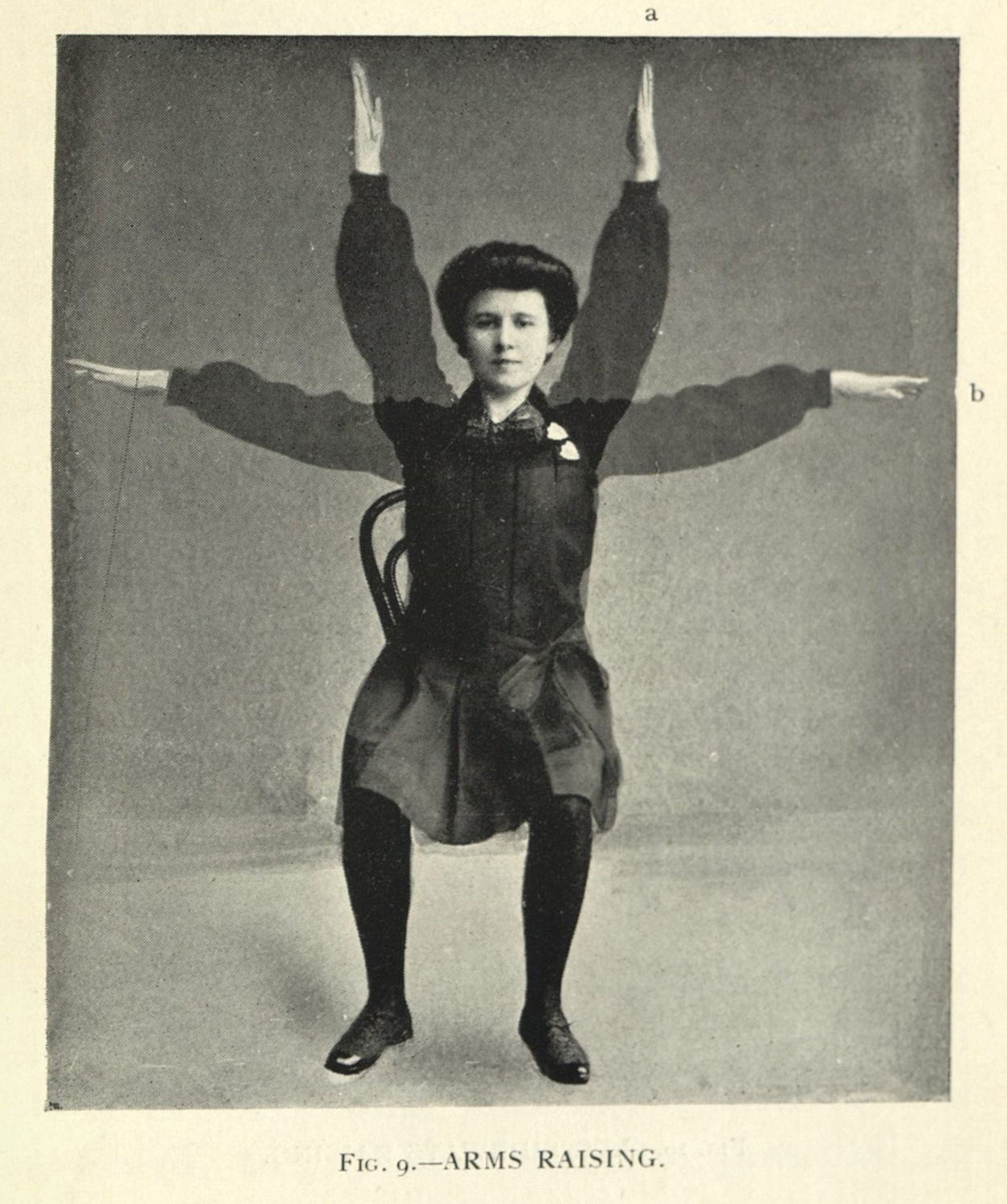

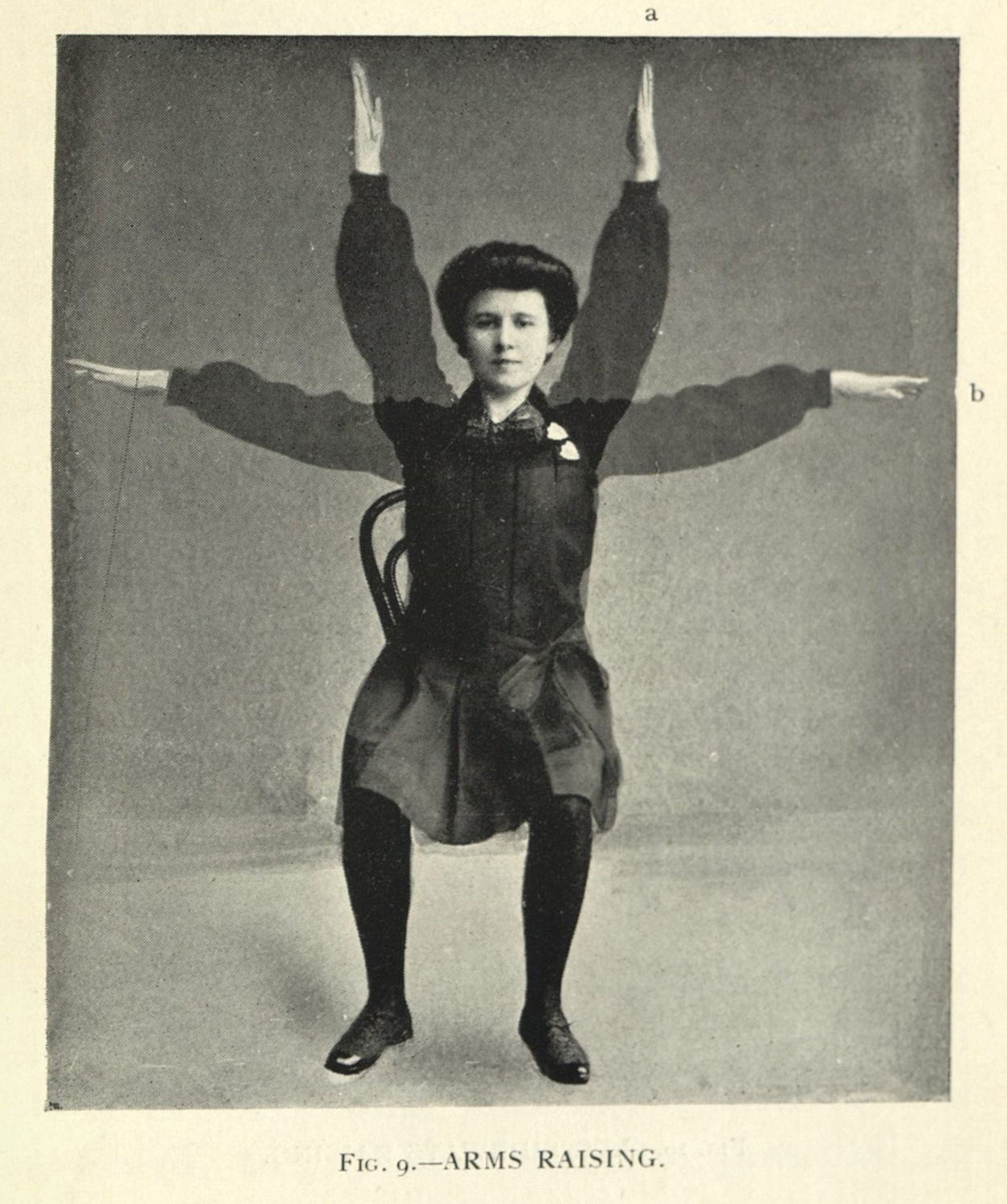

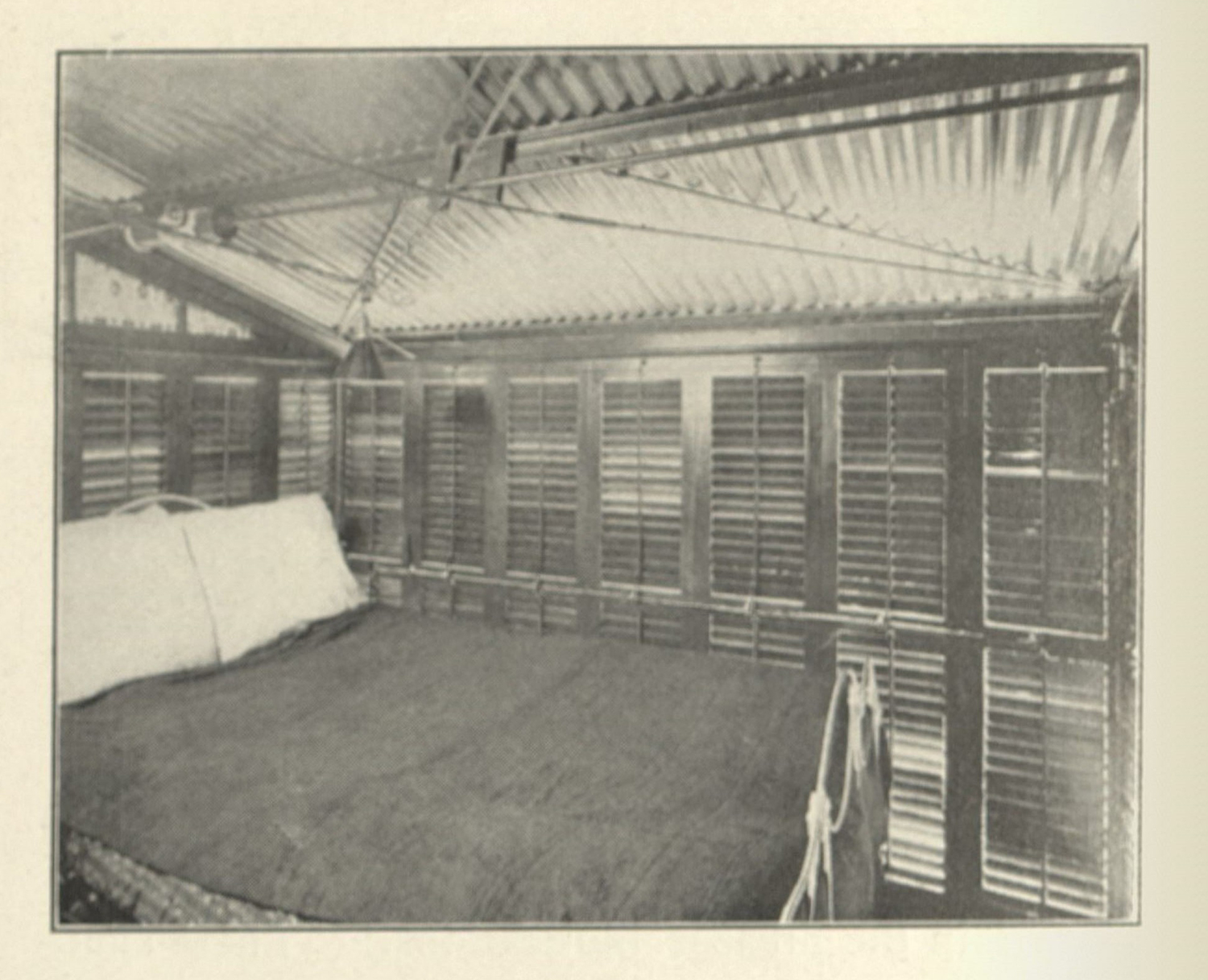

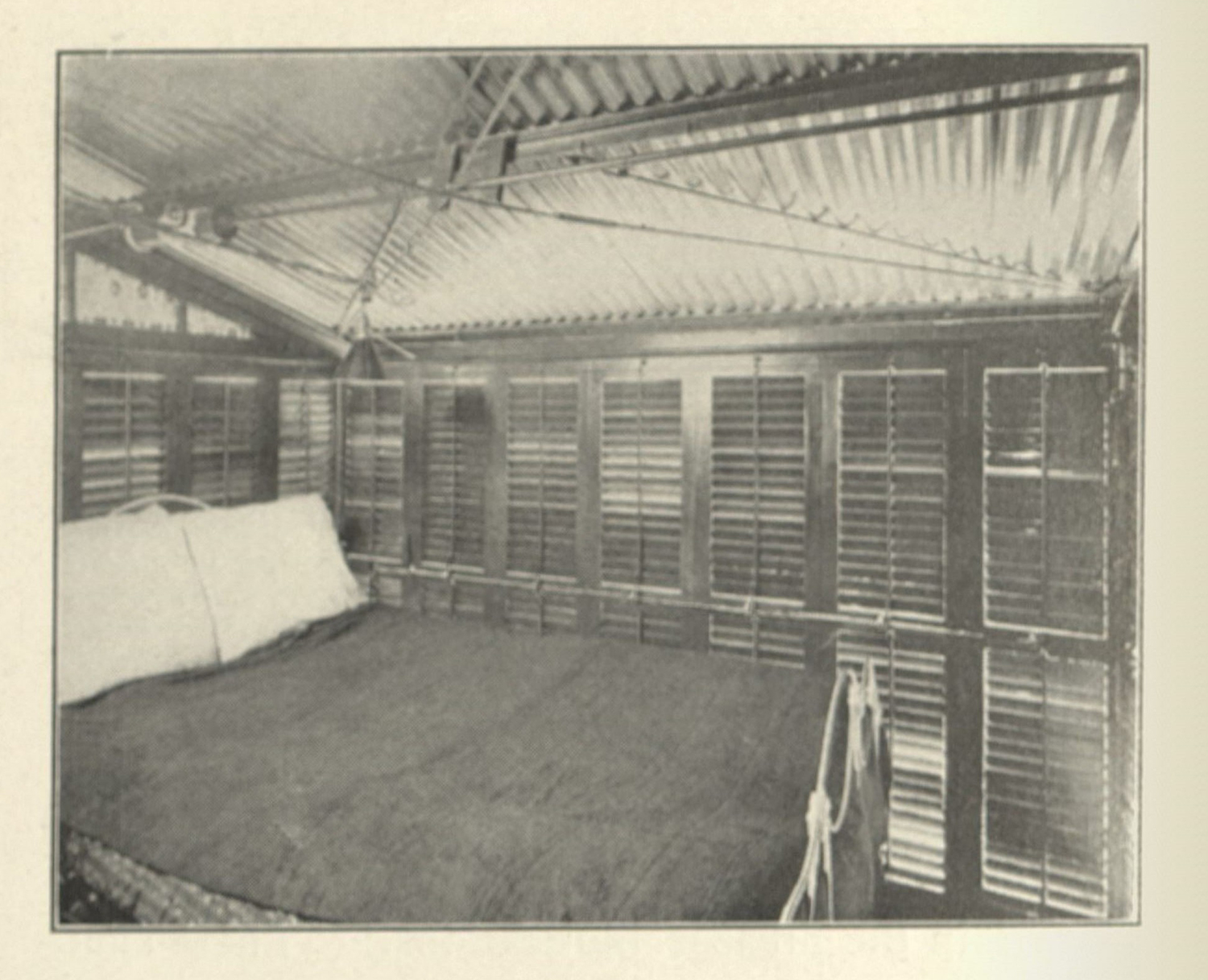

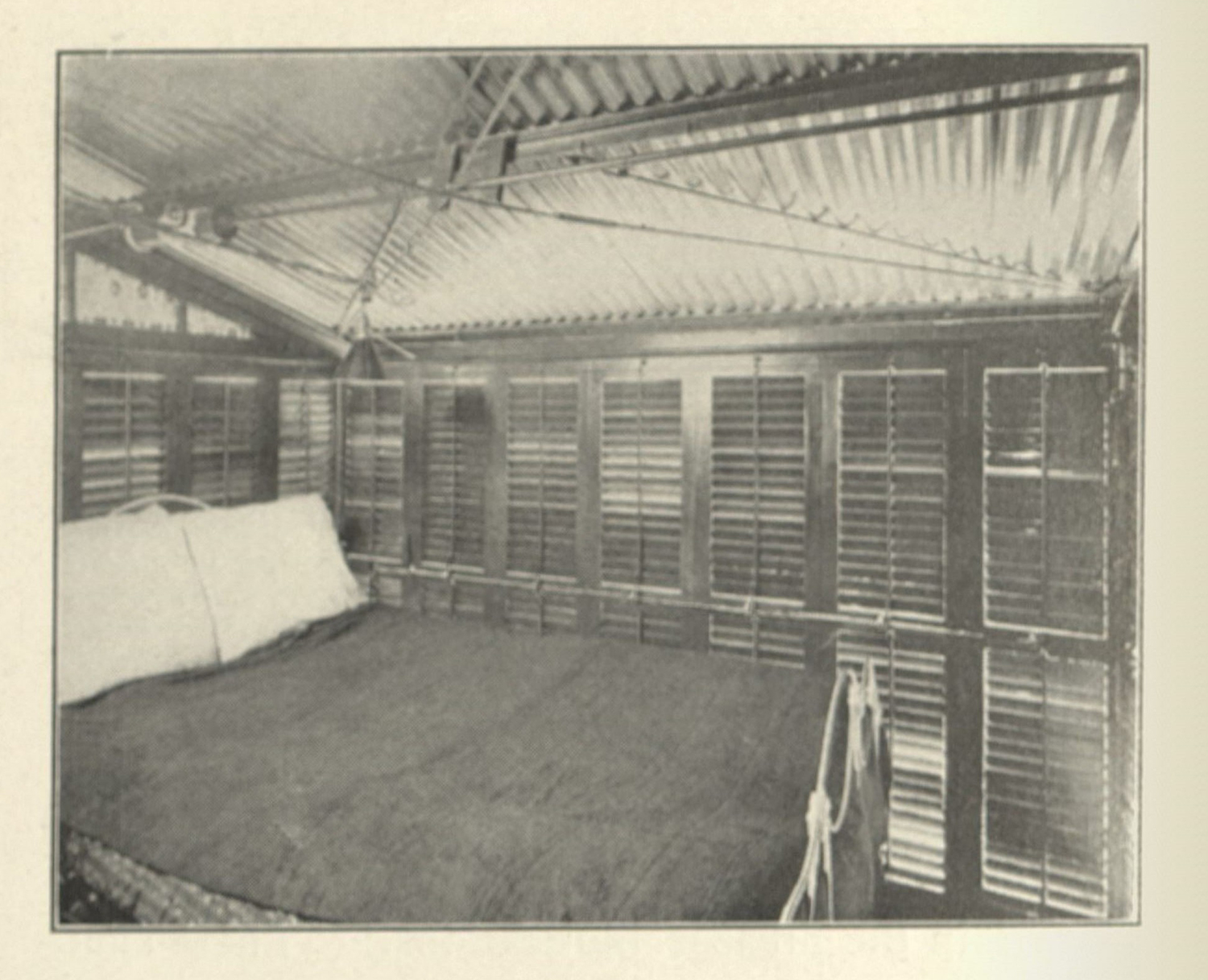

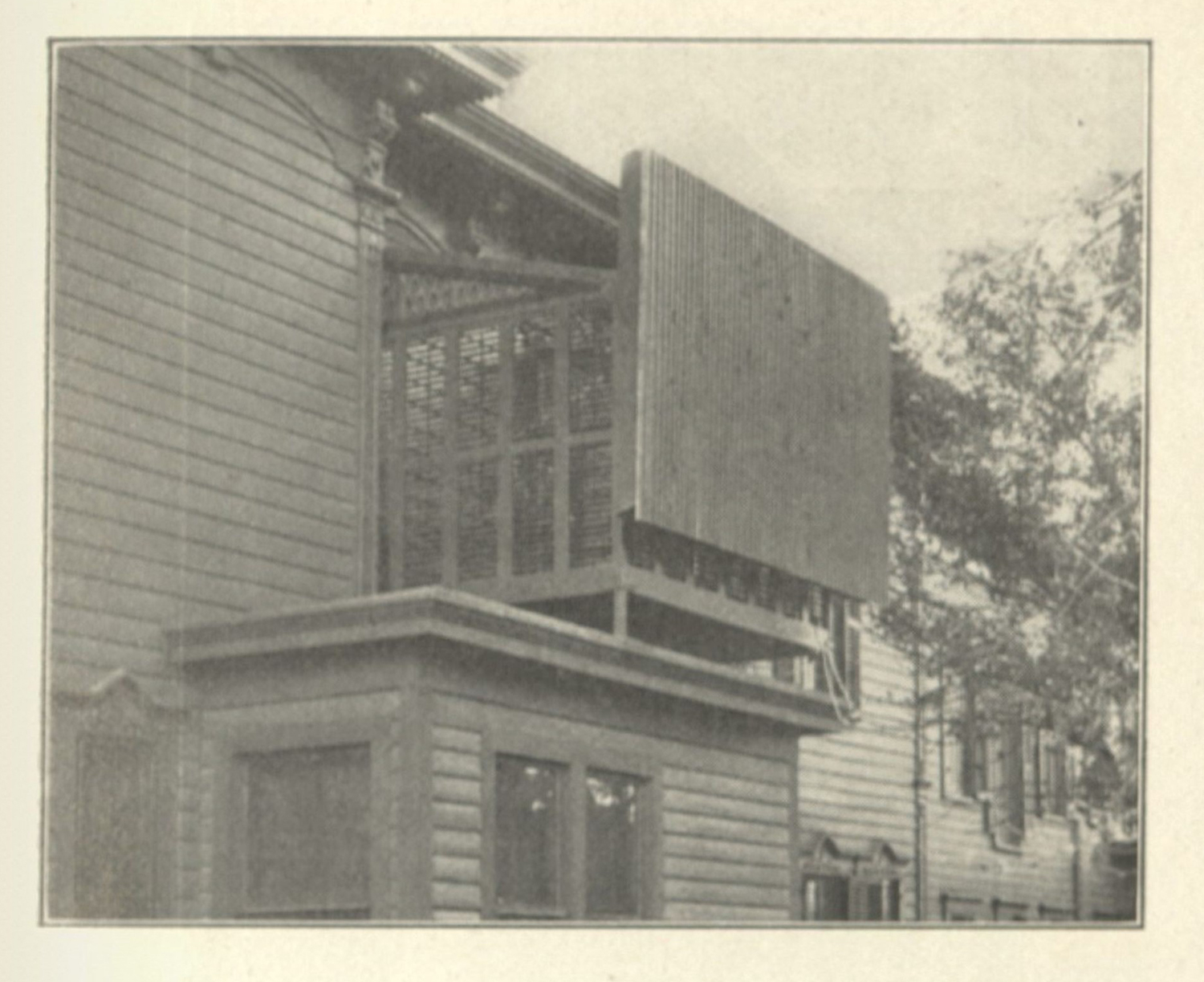

In my research, I have found that while these clinical viewing practices are especially helpful in these regards, they do little to describe broader discourses around health practiced by doctors, public health workers, and the lay public. While there are plenty of images that foreground symptoms, there are just as many photographs of sanatoria facilities (fig. 2), photographs of resting patients (fig. 3), photographs of open-air schools (fig. 4), images of exercise regimens (fig. 5), examples of architectural addons for the rest cure (figs. 6 & 7), and informational graphics (fig. 8).

Figure 2.

Figure 3.

Figure 4.

Figure 5.

Figure 6.

Figure 7.

Figure 8.

A pair of chapters in my dissertation engage with the visual culture around tuberculosis, drawing on both the wealth of images provided by the New York Academy of Medicine, and the images found in a 700 text corpus that I developed through online sources. For this latter collection, I have taken time to create a dataset with metadata for each image found in the corpus, and while myself and my coders are still working through these materials I can provide some preliminary data to support my claims. Out of the roughly 2,700 images me and my colleagues have coded, 741 are tagged as being pathological and 184 are tagged as anatomical (with some overlap in how images are given descriptions, because images can be tagged with multiple keywords). There are almost as many images of sanataria and their floor plans as there are these medical research focused one.

| Anatomical | 184 |

| Pathological | 741 |

| Organ | 126 |

| Diagnostic | 176 |

| Microscopic | 111 |

| Treatment | 163 |

| Architectural | 779 |

| Group | 300 |

| Child | 234 |

| Advertisement | 2 |

| Equipment | 211 |

| Portrait | 483 |

| Hygiene | 101 |

| Exhibition | 63 |

| Sensitive | 63 |

| Map | 4 |

| Animal Specimen | 77 |

| Professional | 29 |

| At Work | 32 |

| Other | 127 |

| 4006 |

I make this case to speak to the kind of work that is still necessary in visual culture analyses of the history of medicine: the ways doctors, patients, public health officials, and the broader public all saw health is much messier than the clinical gaze affords. Echoing a plural turn made by a number of other cultural scholars, I want to think in the frame of “visual cultures” rather than a monolithic visual culture defined solely by the clinical gaze.

I wanted to stress the concept of visual culture in this essay partially because this is an interdisciplinary group and I don’t want to alienate anyone here, and partly because I want to use this visual culture framework to voice a problem that I have been having in my research. Clinical vision is very helpful in describing all kinds of images, but it starts to strain when we consider multiple viewing subjects, when we consider the ways patients might have had agency in the ways they were photographed,3 when we consider the non-human contexts of medical research, and when we are forced to conceive medical imaging practices as bespoke rather than monolithic.

With this in mind, I want to deflate clinical visuality, to think of its representations in the historical sources as a genre of image emblematic of a dominant kind of looking, which competes with other visualities. To do this, I am going to work through some images from the New York Academy of Medicine’s historical collections, with the interest in developing an understanding of what I want to call a “pathological portrait”. Specifically, I am using the term portrait to describe the ways these images tend to isolate and emphasize a single object in their frame, usually single-mindedly ignoring the other visual material which just so happens to be necessary in the framing of the shot. My interest here is to eschew the more technologically determined term “clinical photograph” which forecloses non-photographic representations of clinical symptoms, to stress a need to include non-human and microscopic subjects in the discussion, and make space for further discussions of more slippery conceptions of medical vision.

Tuberculous Portraits

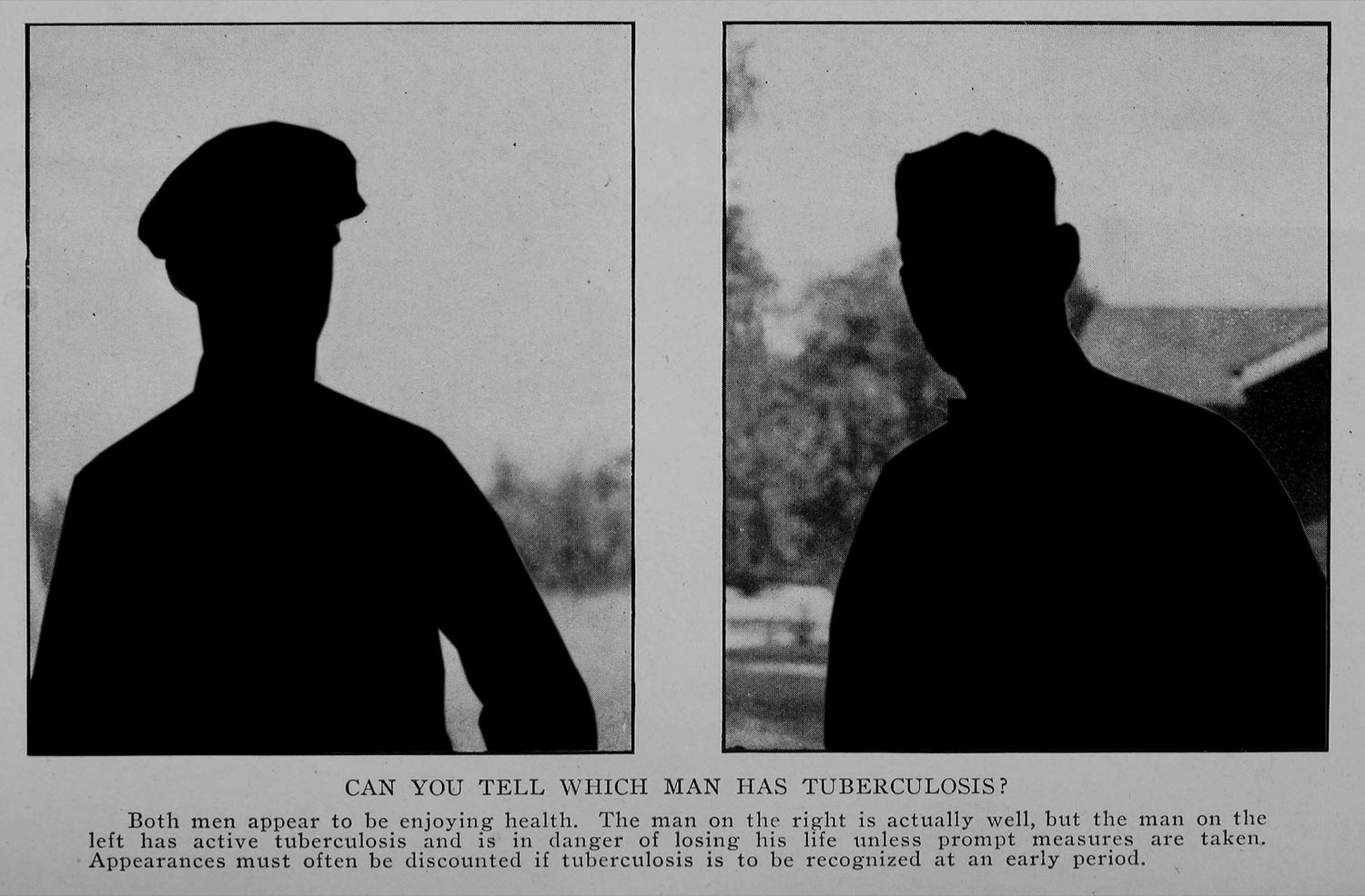

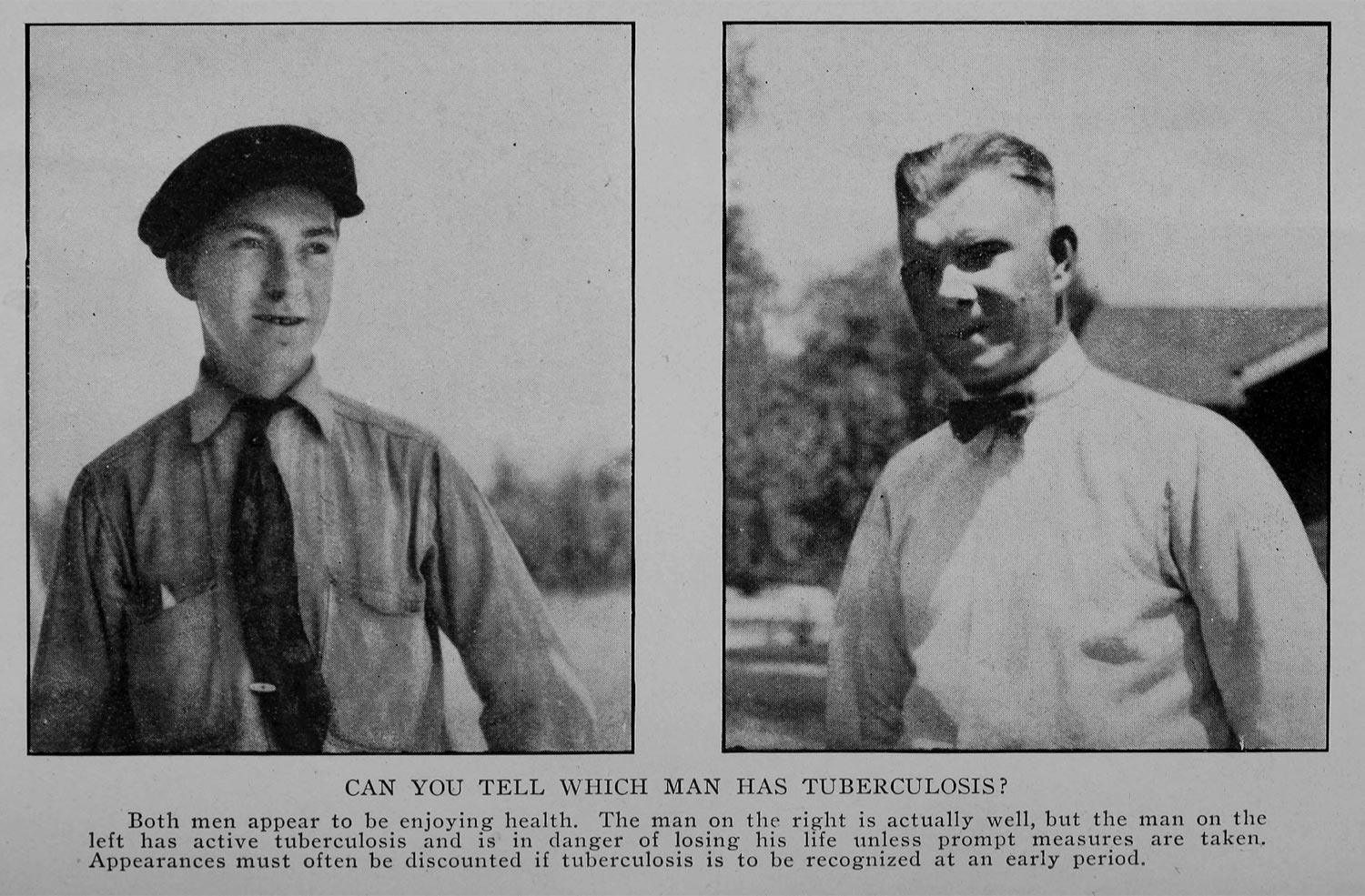

Let’s start with two images found sitting next to one another in a book by Charles E. Atkinson (fig. 9). Published in 1922 Lessons on Tuberculosis and Consumption for the Household was meant to inform the public about the disease and approaches to addressing the chronic infection. I start with these images because they stress a kind of conceptual and epistemic rupture with traditional clinical visuality; specifically, doctors were not always able to see the disease on the bodies of their patients, and the caption to this image makes this apparent. The caption argues “appearances must often be discounted if tuberculosis is to be recognized at an early period.”4

Figure. 9. Charles E. Atkinson. Lessons on Tuberculosis and Consumption for the Household. (New York & London: Funk & Wagnalls Company, 1922).

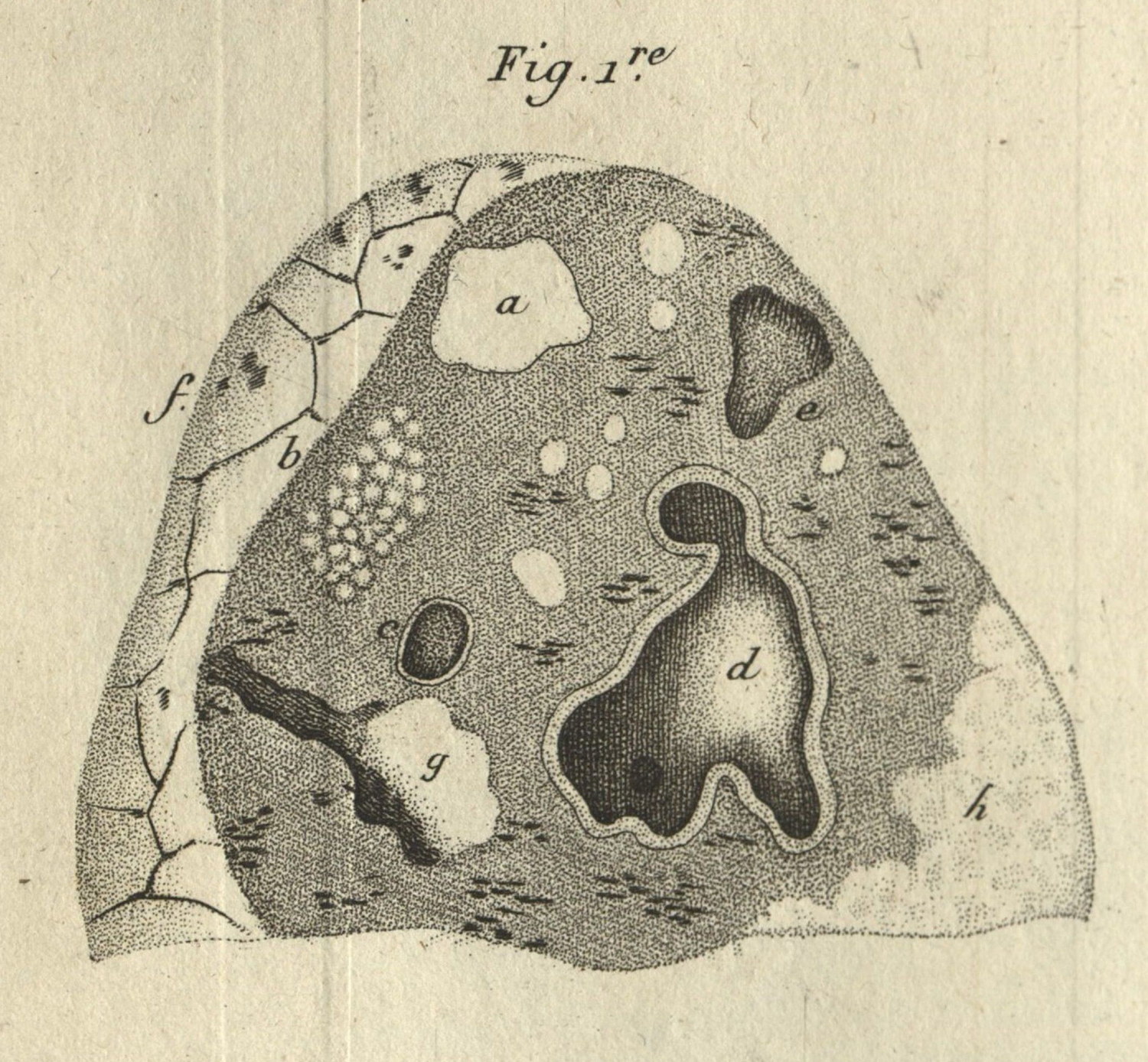

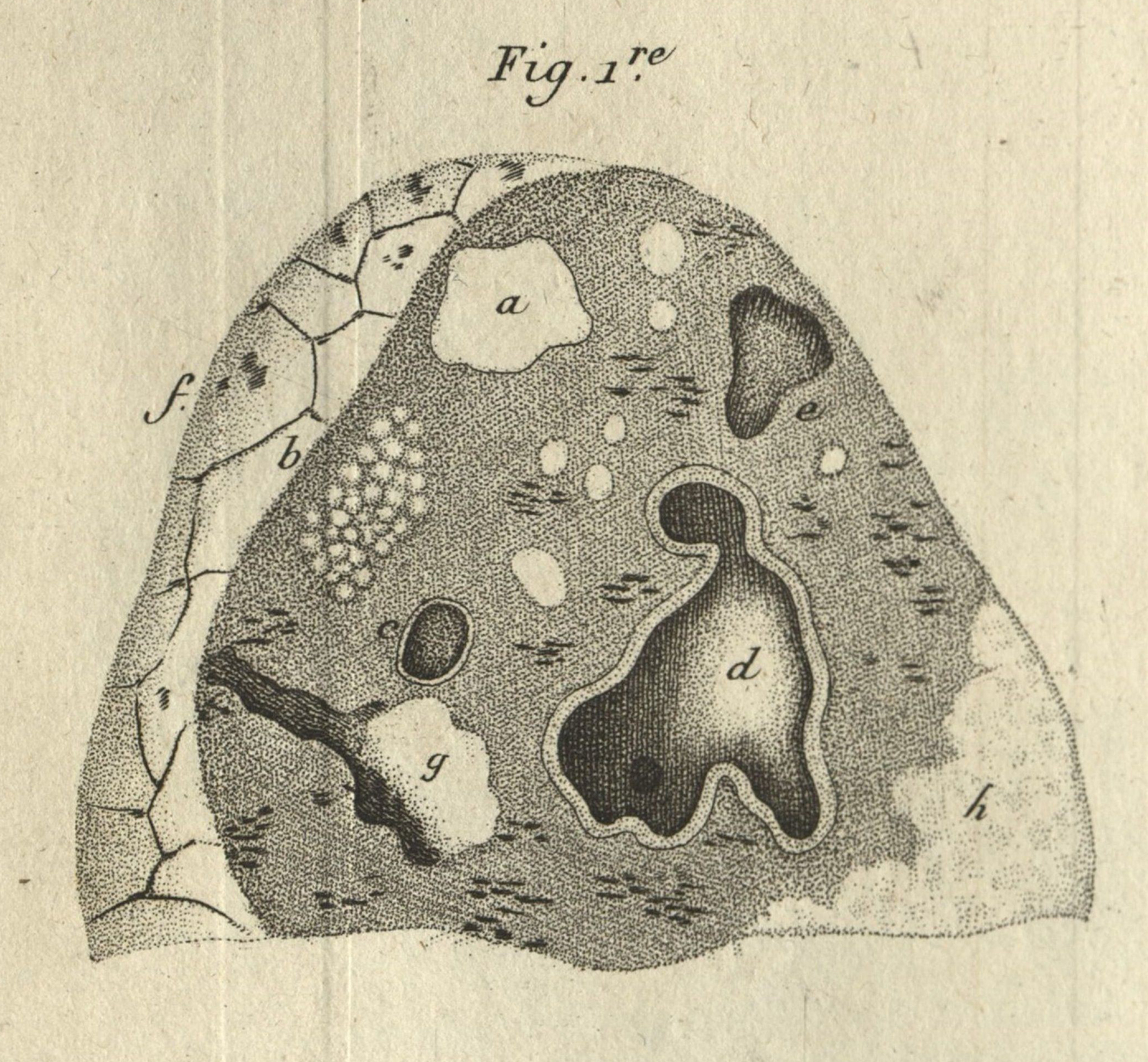

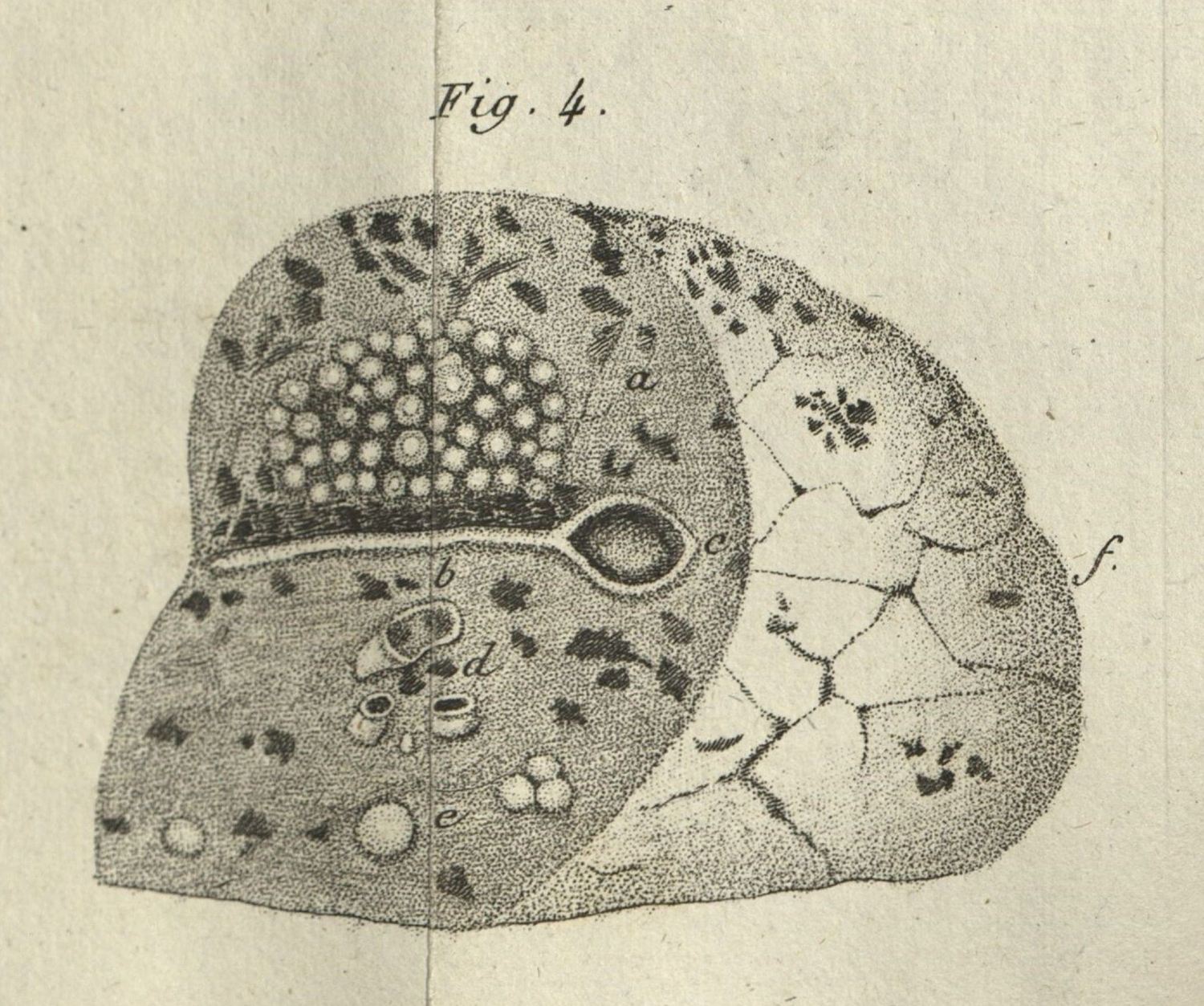

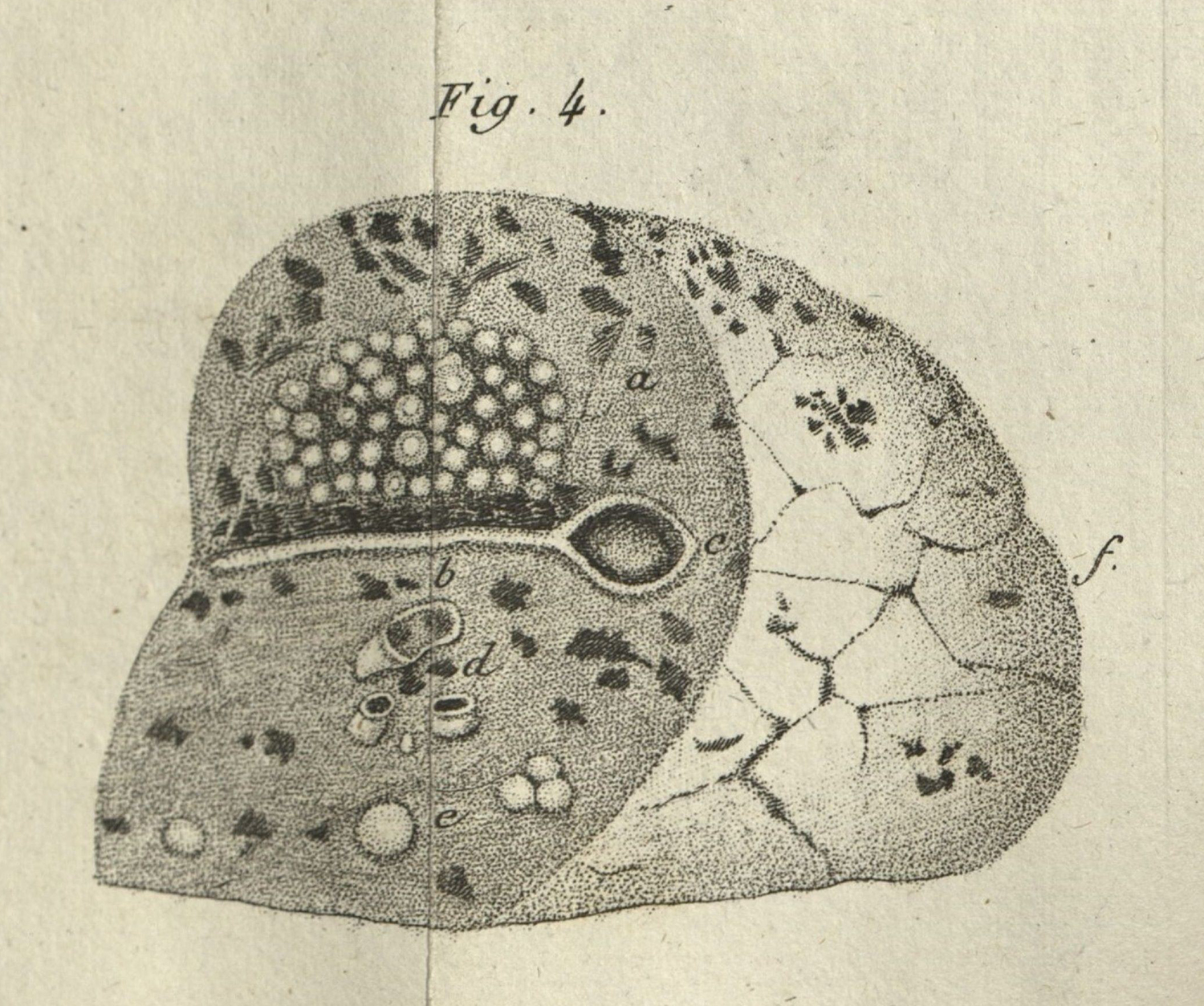

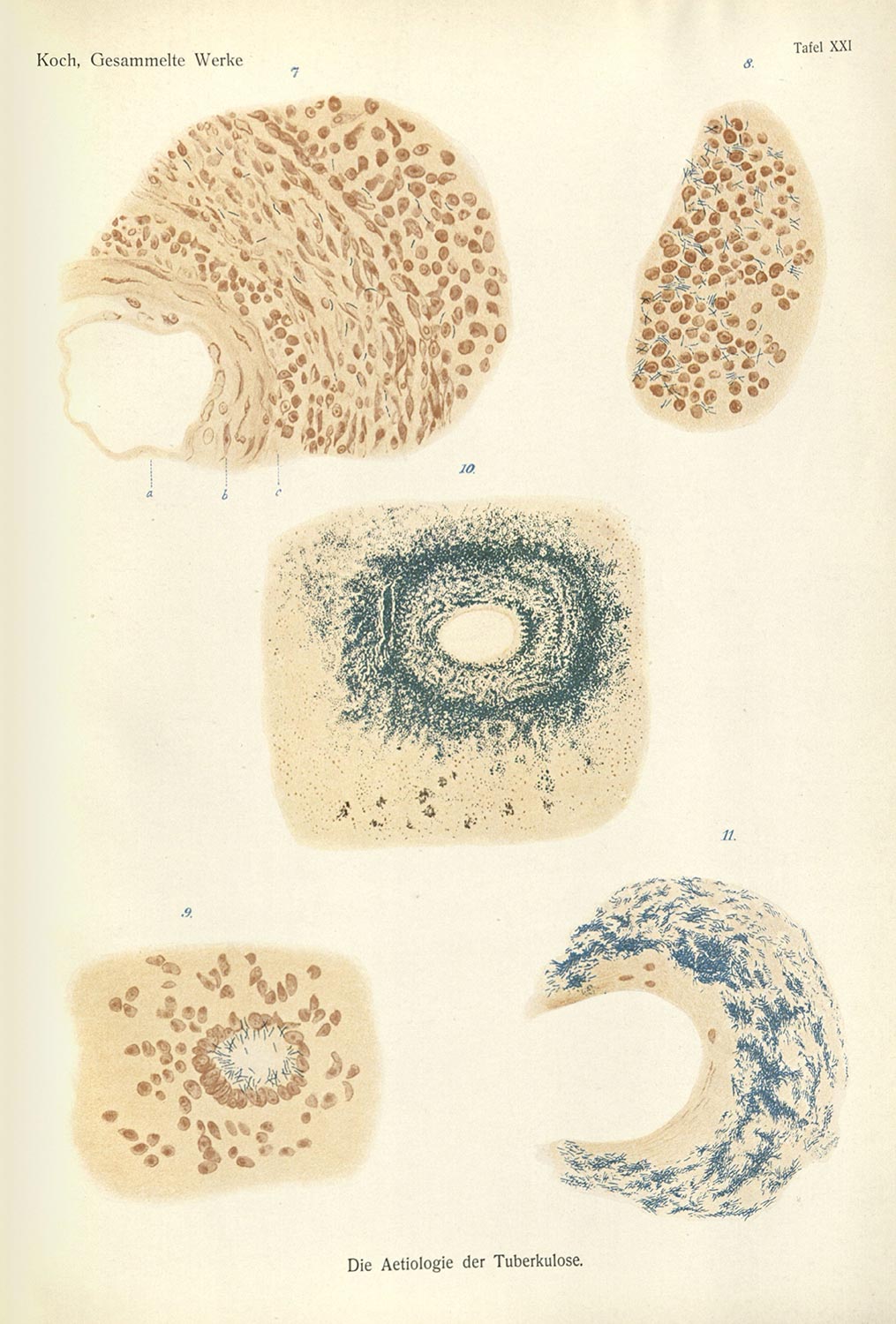

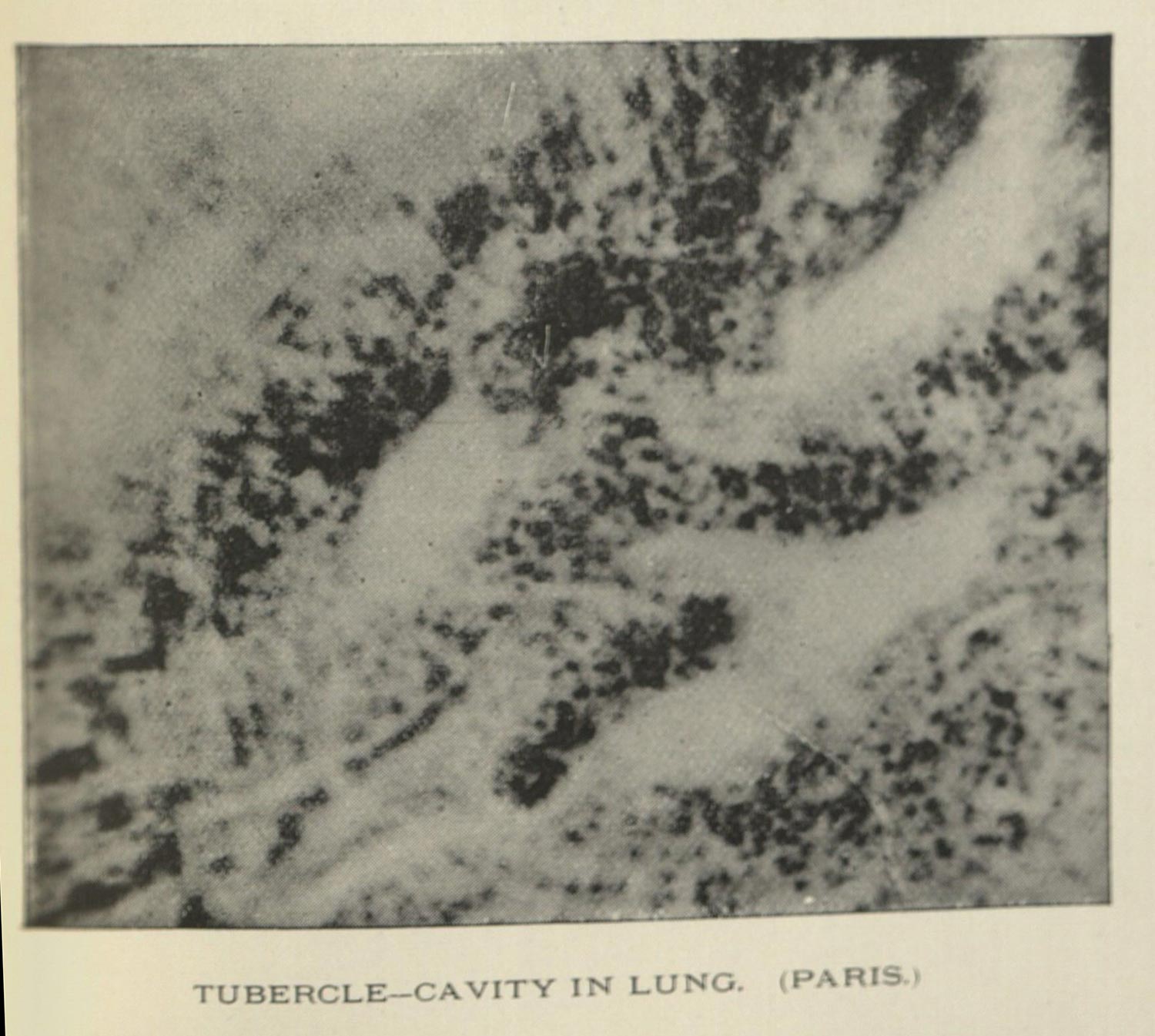

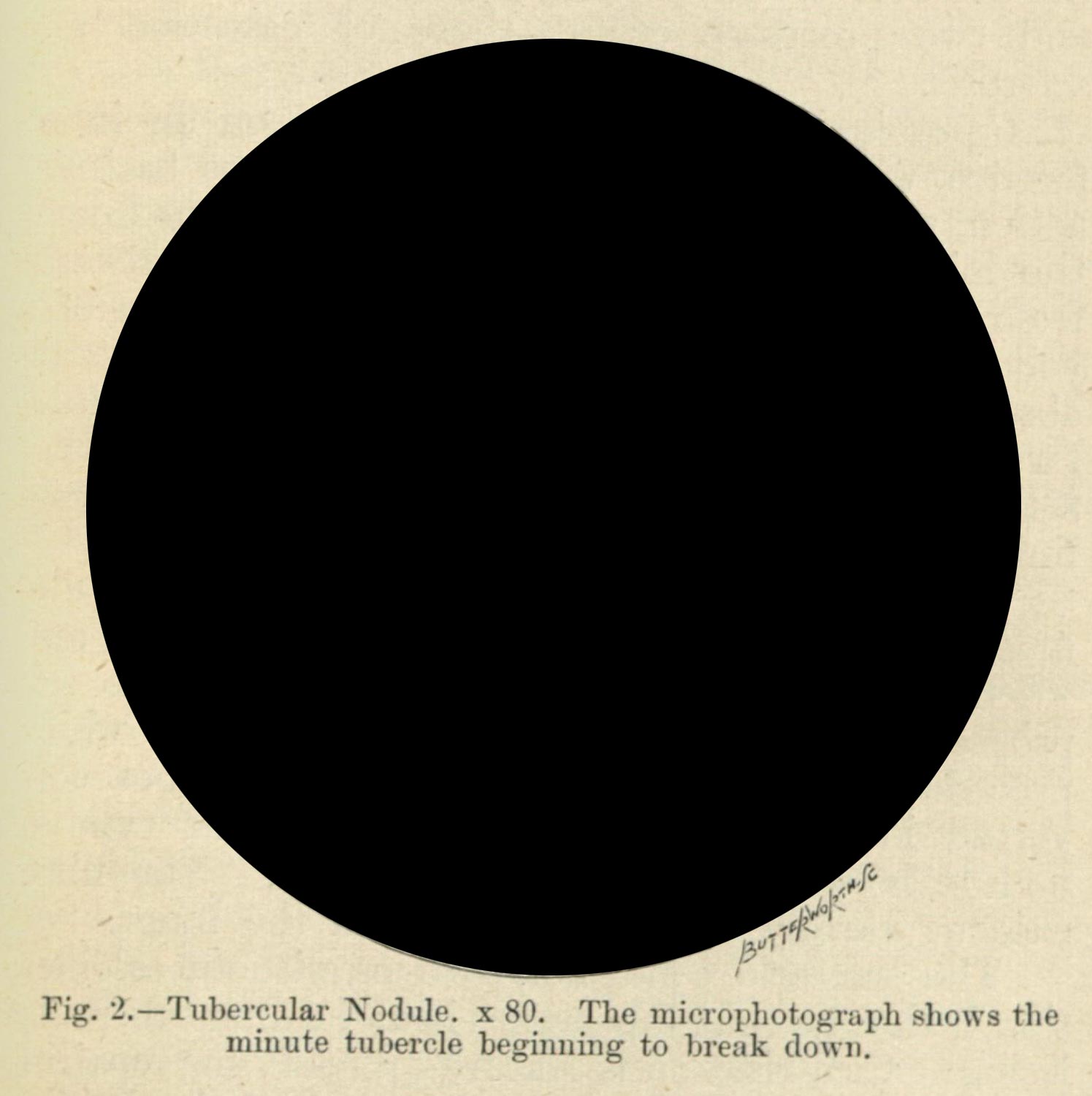

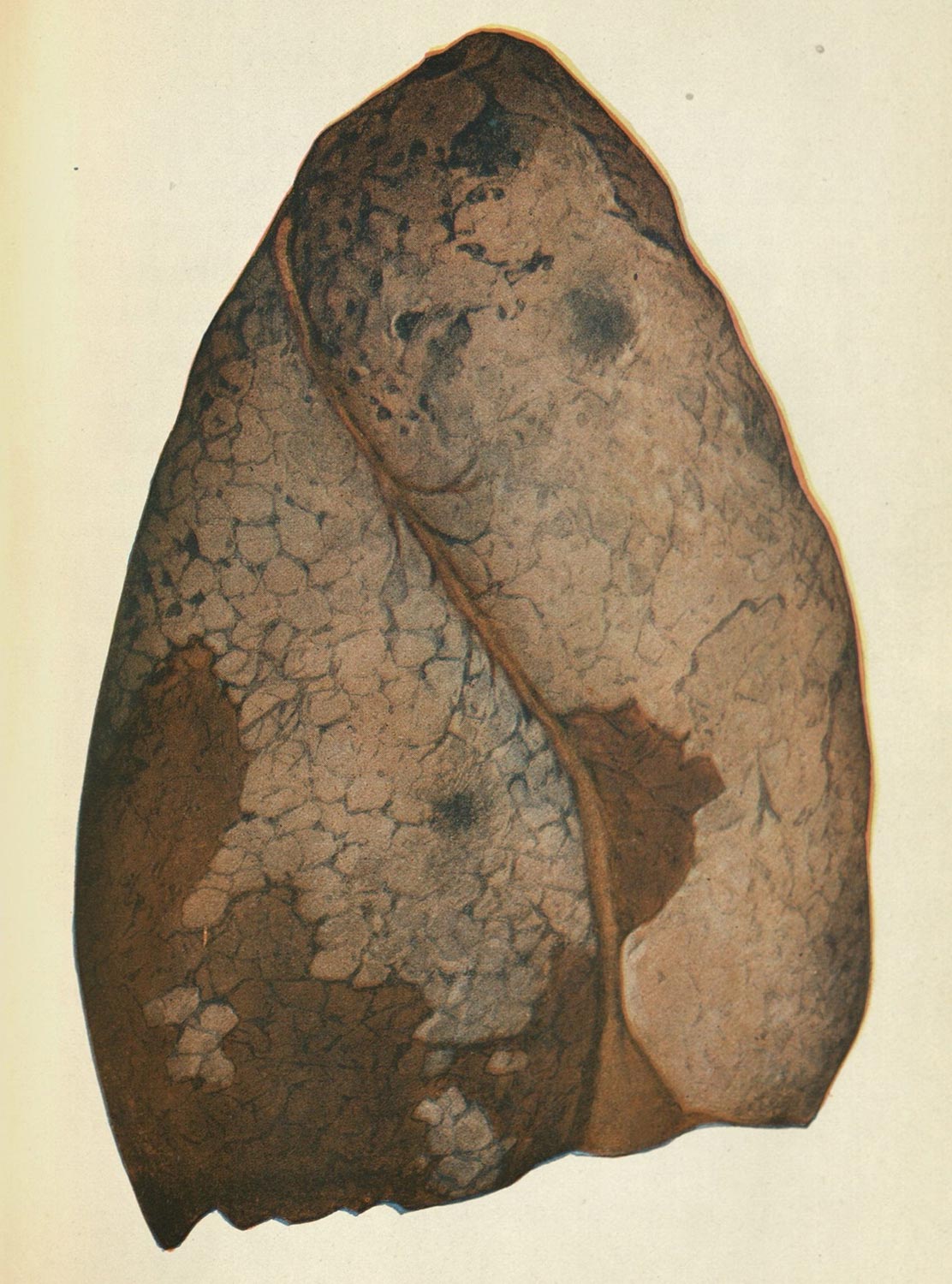

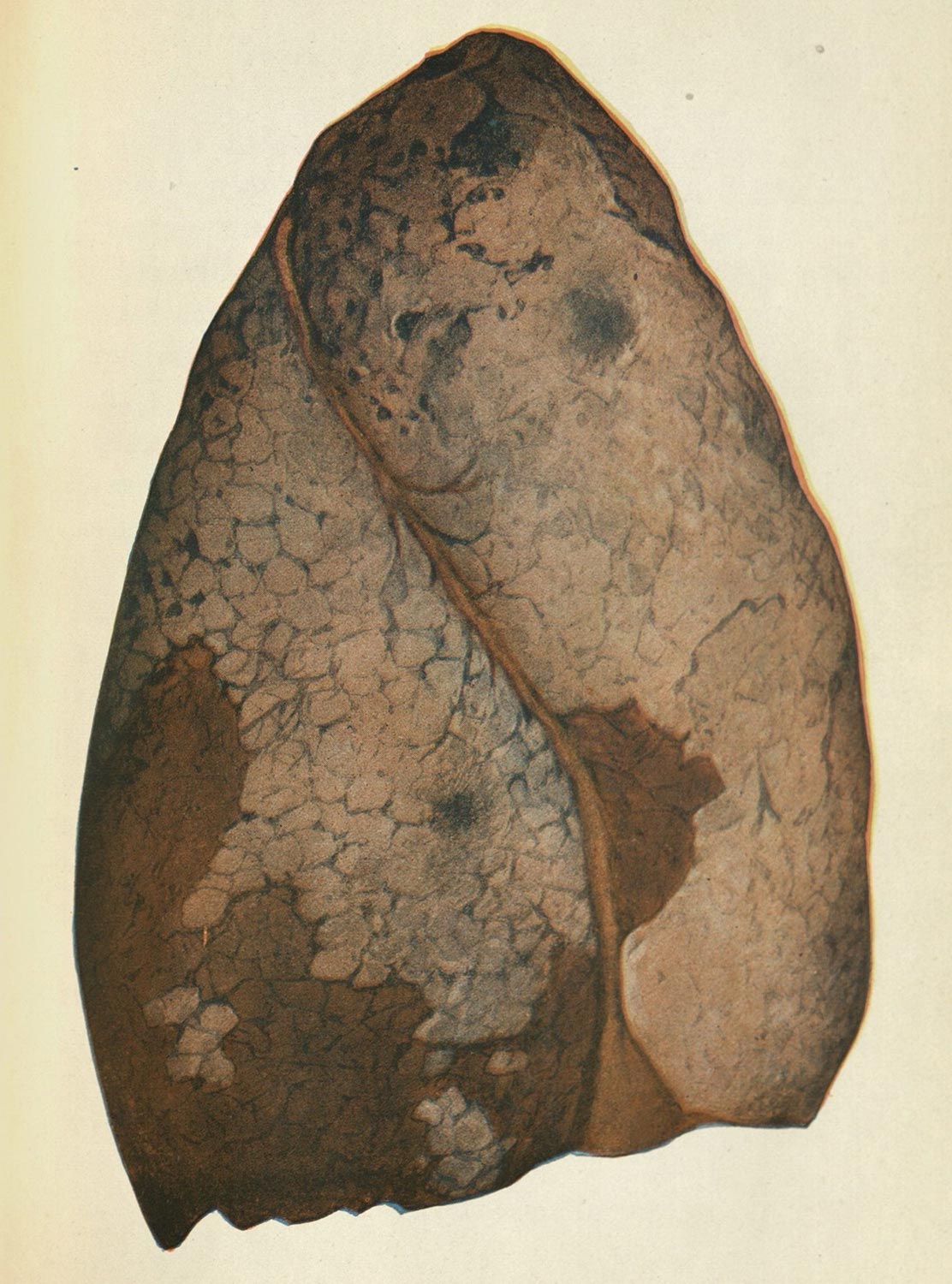

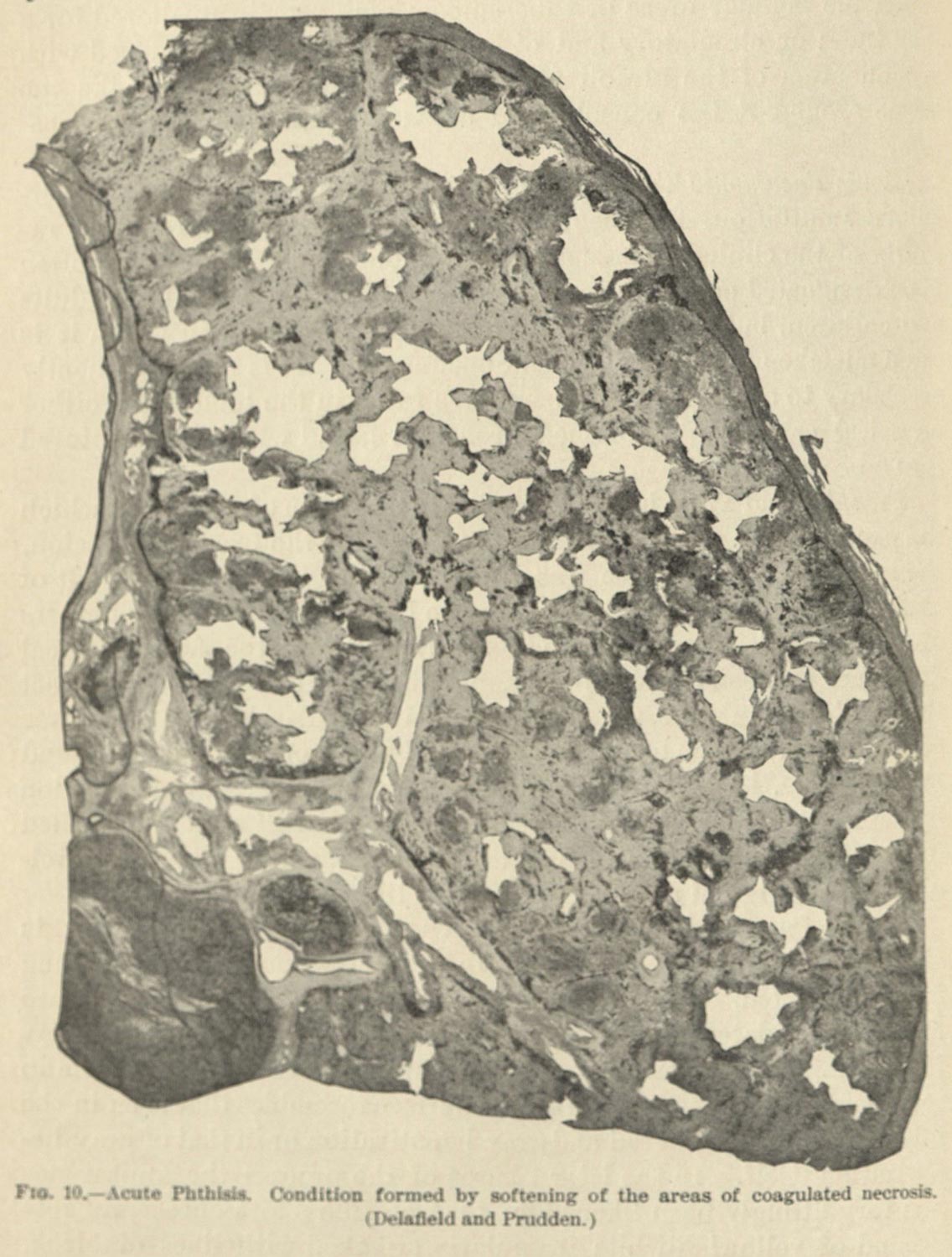

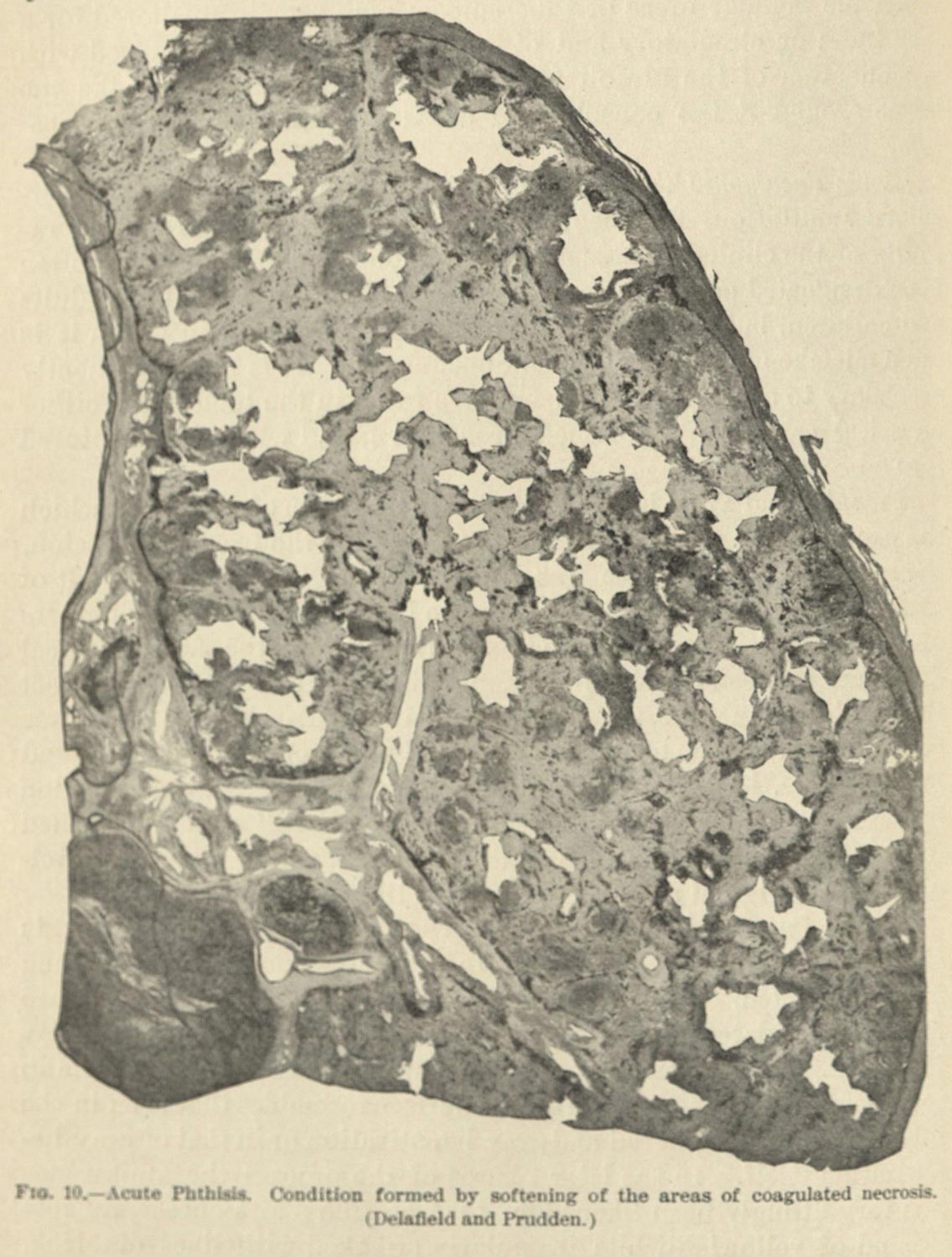

Tuberculosis generally affects patients in the form of a chronic infection. A slowly reproducing microbe, it takes hold in the body in small, hardened massess, known as tubercles. French physician René Laennec is credited for first documenting these masses in the lungs of autopsied patients, and it is from Laennec’s arguments that the tuberculosis got its modern name (figs. 10 & 11). The mallady was understood for centuries as a wasting disease—“consumption” or “phthisis” as it was known in the period was argued to be the result of a hereditary, constitutional failure, as sick patients would slowly waste away over a series of months or years. It gained a kind of notoriety during this period as an artist’s or poet’s disease, having famously affected Romantic poet John Keats.5 In 1882, Robert Koch argued for a microbial cause of the condition, tying the mallady to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. This germ theory driven understanding helped link some other conditions (not thought to be related to “consumption”) to the same microbial cause. Moreover, the shift to germ theory brought with it a larger issue for clinical visuality: how are we to understand visuality in relation to something that is not readily visible to the naked eye? What are we to do with a clinical gaze that demands a microscope?6

Figure 10.

Figure 11.

For tuberculosis researchers in the first decades of the twentieth century, there were competing approaches: some tying visible symptoms to diagnosis, and others stressing the need for a positive sputum test. Sometimes doctors would assume tuberculosis even with a negative test, and sometimes these negative tests would be used to claim that the patient was fully cured, only for the patient to return some years later with another case of advanced disease. Clinical vision, which assumes the ability to see disease, becomes increasingly mediated: to see someone as sick is only through the aid of other technologies and practices: specifically the sputum test. (A side note here: in the decades following my historical range, doctors would standardize the use of x-rays for diagnosis.)

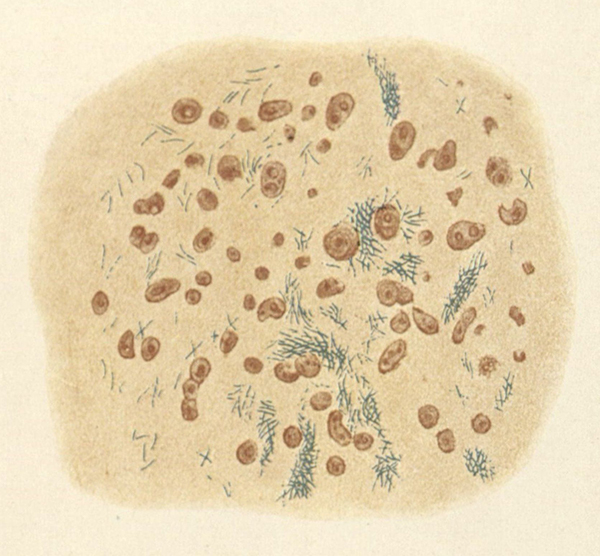

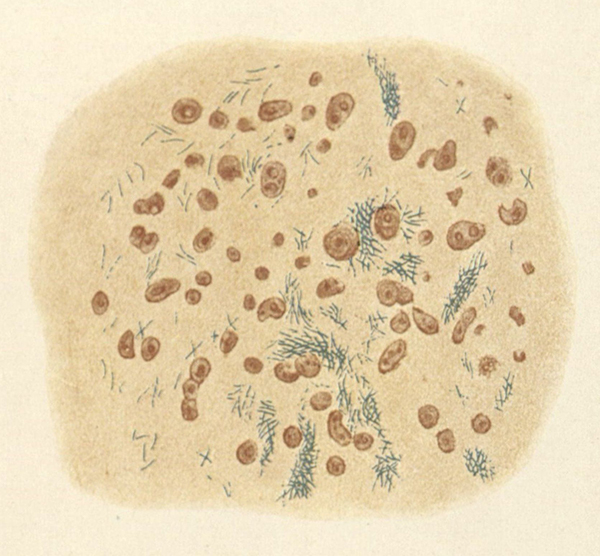

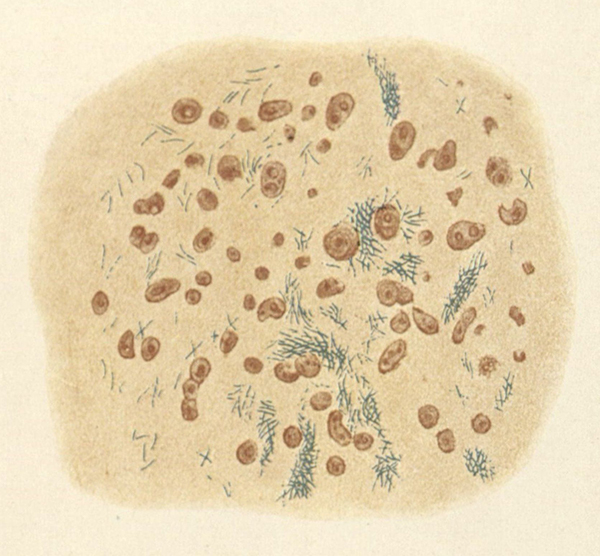

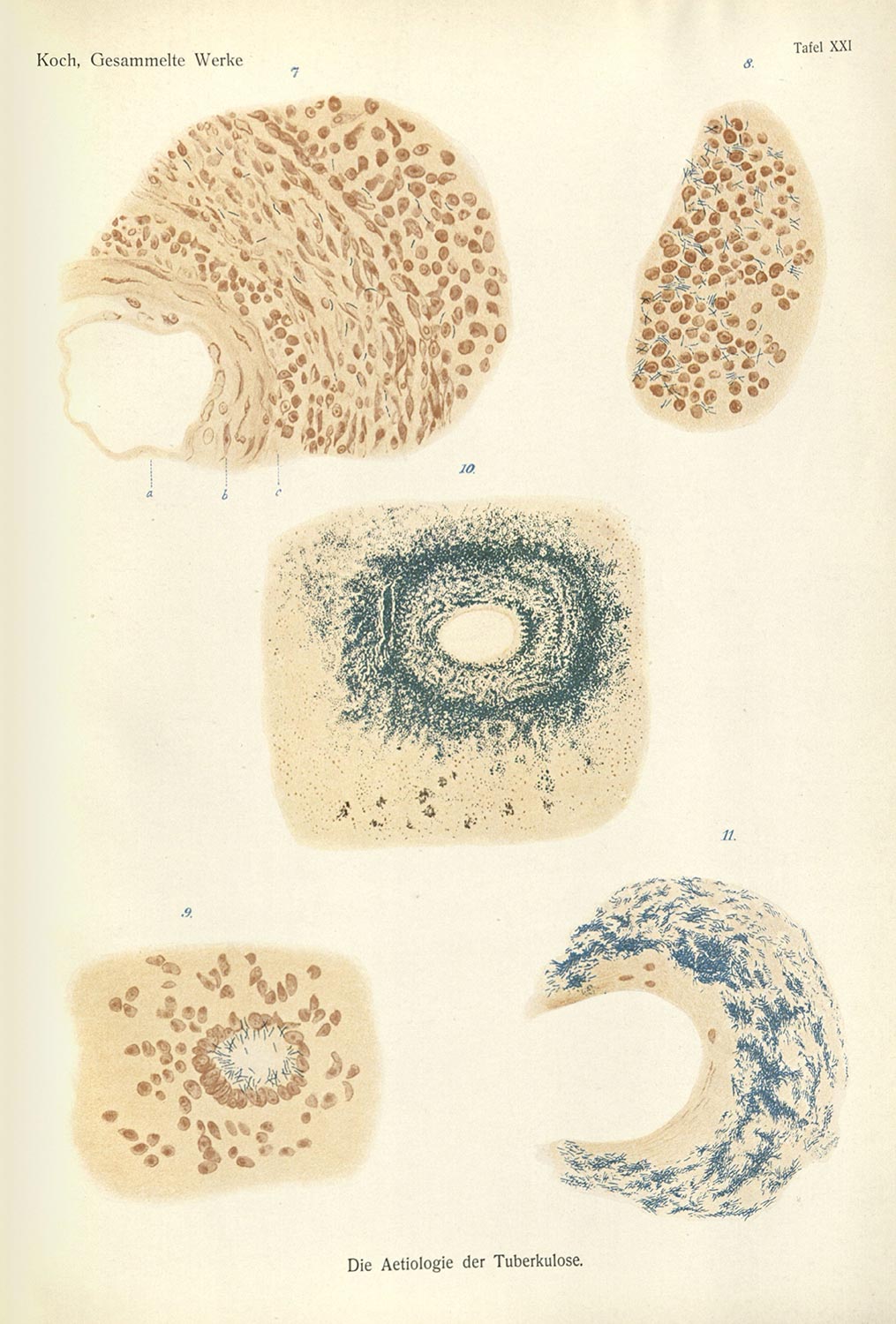

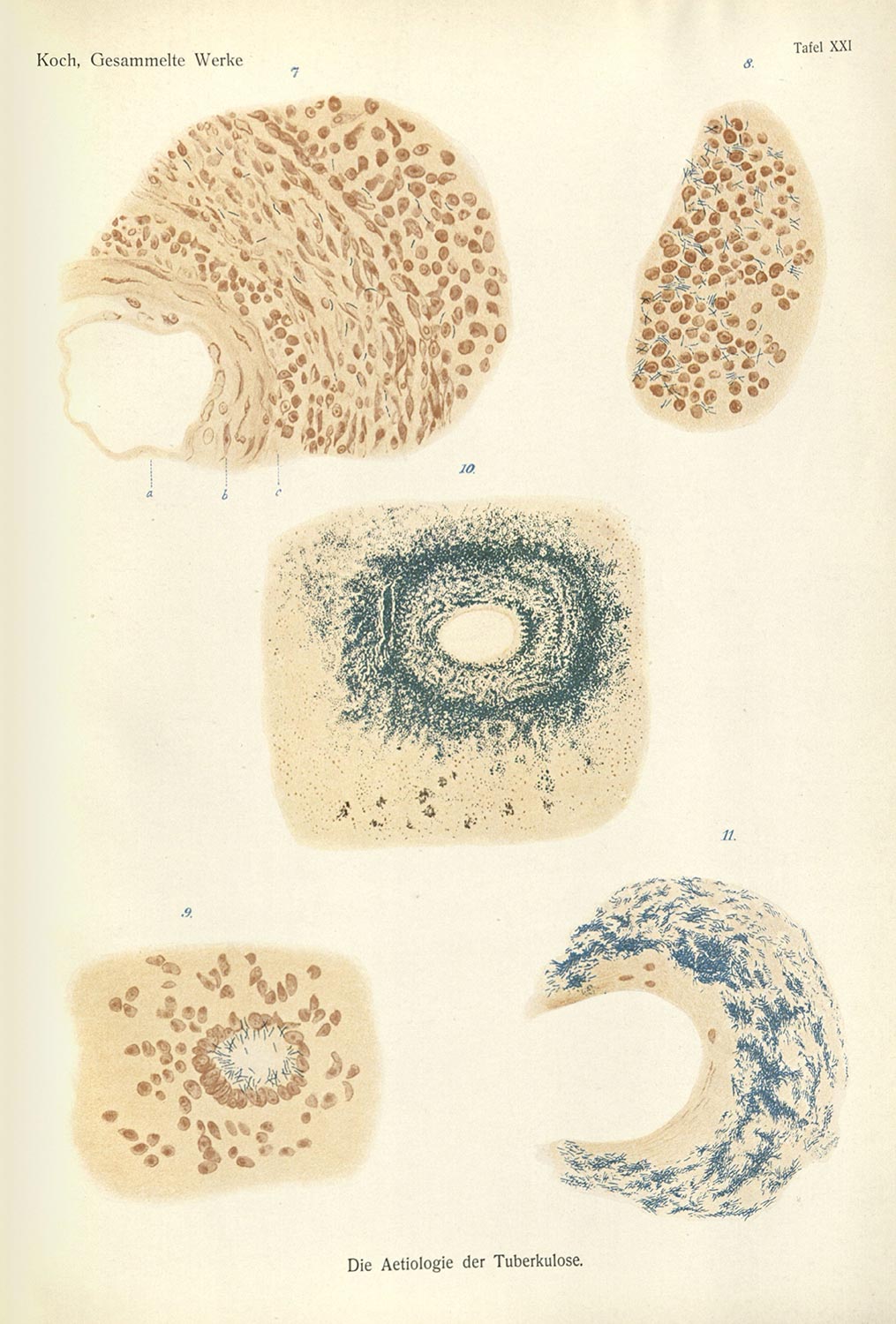

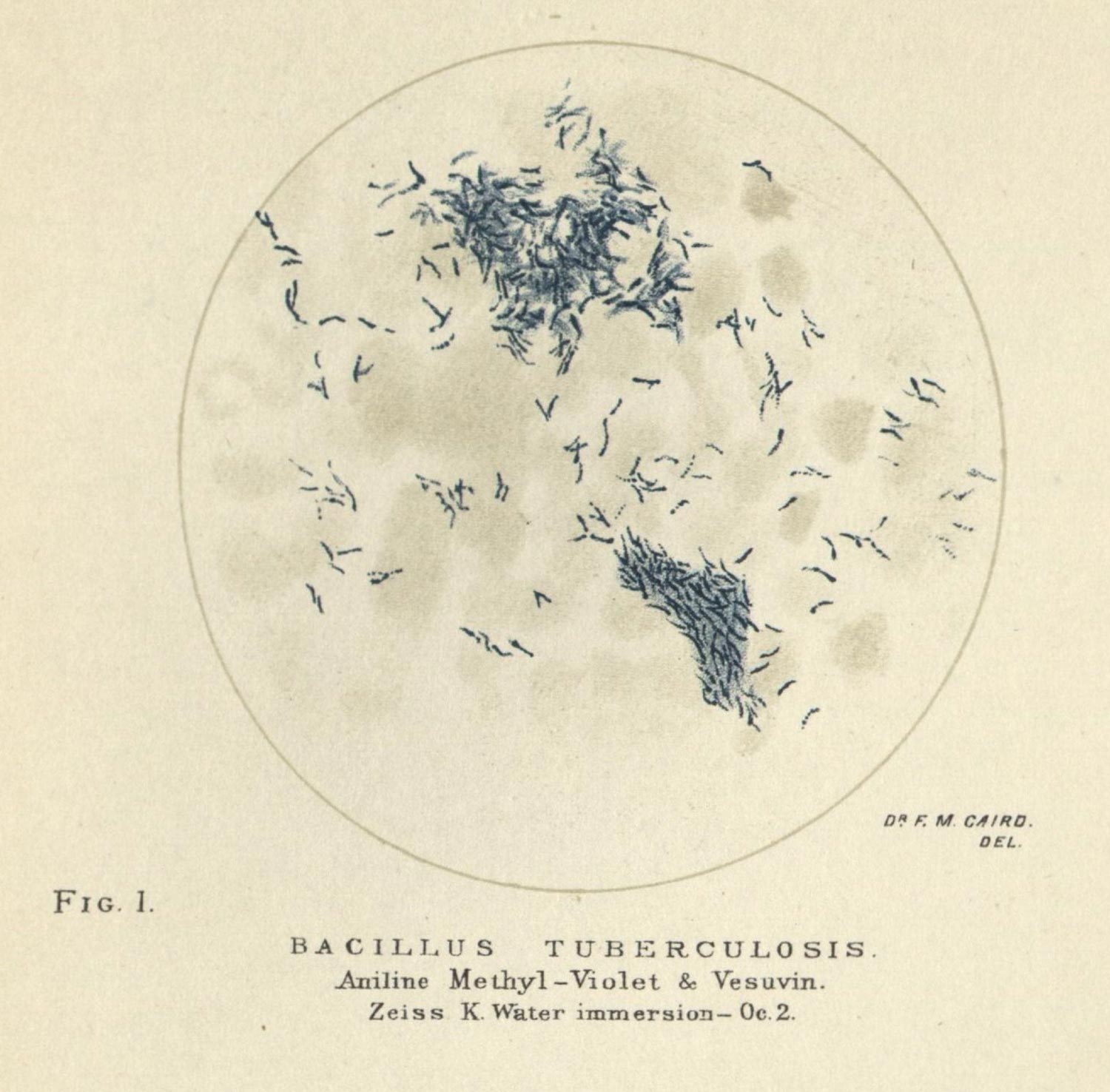

To describe what I mean when I say that tuberculosis’ visual culture became increasingly mediated, I want to move back to 1882, and Robert Koch’s influential research into the microbial cause of the disease. I have a set of images that accompanied the publication of Robert Koch’s Etiology of Tuberculosis (fig. 12 & 13). This is a landmark essay in the study of germ theory, most famous for the concretization of Koch’s postulates—or the conceptual framework that still undergirds germ theory. For today, though, I am less interested in Koch’s conceptual work, so much as the ways vision helped convince his colleagues (many of whom vehemently opposed germ theory) of his microbial claims.

Figure 12.

Figure 13.

To produce these images, Koch developed a process of isolating and incubating Mycobacterium tuberculosis in the bodies of guinea pigs. Tracing the disease in uninfected animals, and the ones in which he injected with the bacteria, Koch autopsied the remains of these guinea pigs. Taking the tubercles, crushing them onto a plate, and then processing them with a series of acid baths, Koch was able to make the tuberculous bacteria visible: making representations where the blue bacteria brightly contrasted against the other cellular material nearby.

The images were made possible by Koch’s conceptual and practical labor, but also by a set of larger shifts in the practices of medical science. The first was the gradual adoption of microscopy as a research practice. While microscopes had been around for centuries prior, technological developments, like those made by J. J. Lister dealt with some of the optical noise of early microscopic devices.7 These technological changes occurred in parallel with a change in how the microscope was used. No longer a novelty device, microscopy (and its aesthetics) were being taught in European universities and adopted more readily by medical scientists and natural historians.8 The second shift was the development of practices of histochemistry—or the study of how chemicals react with the anatomical parts of microorganisms. Koch specifically quotes the work of Paul Ehrlich and his processes of dying microscopic objects, and developed his own methods in discussion with this emergent practice.

All of these technological, cultural, and epistemic changes assisted in the production of Koch’s 1882 study, mostly because of what they allowed Koch to do: they let him see and count the stilled microbes, and they let him show these objects to his colleagues.

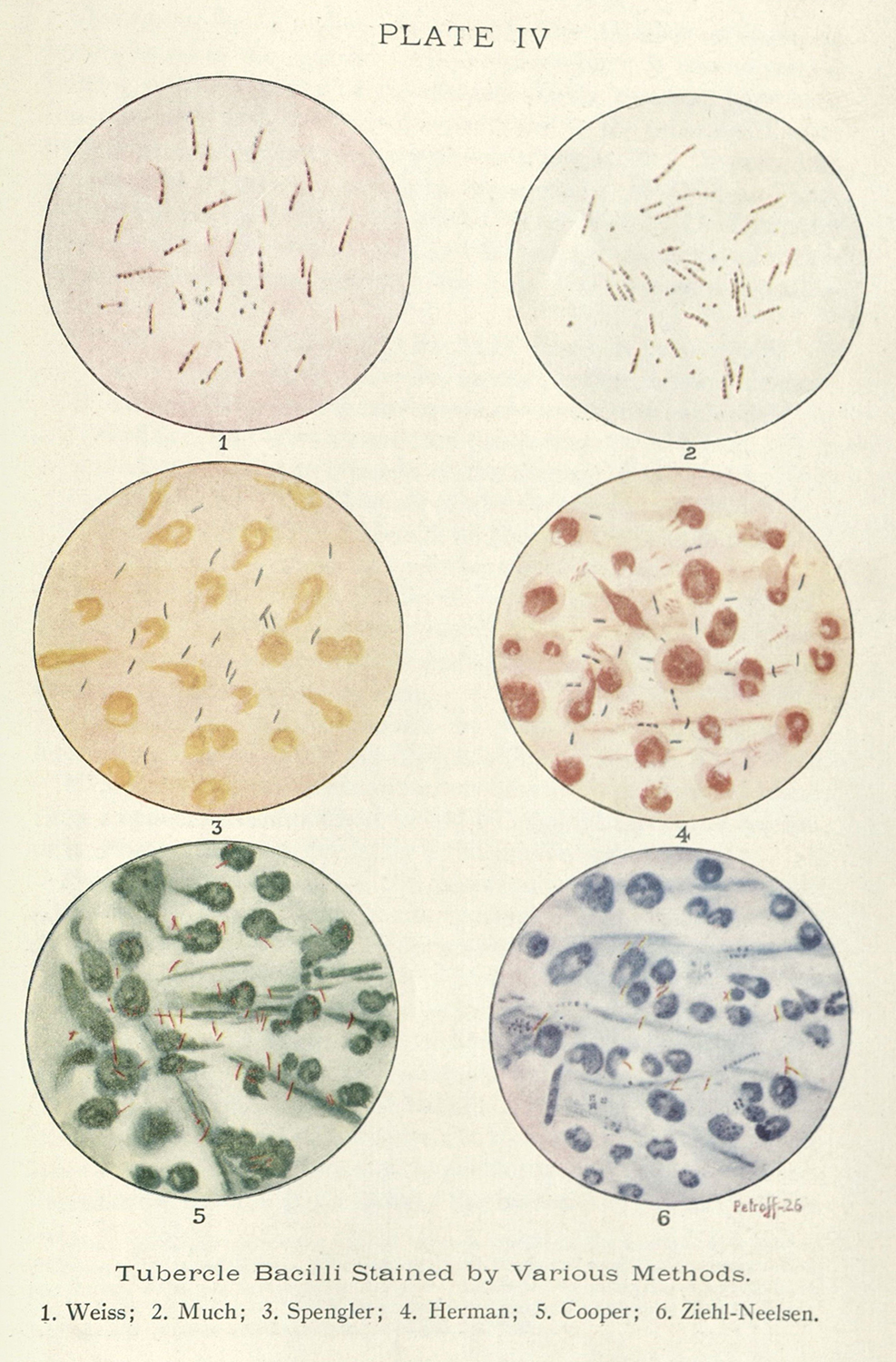

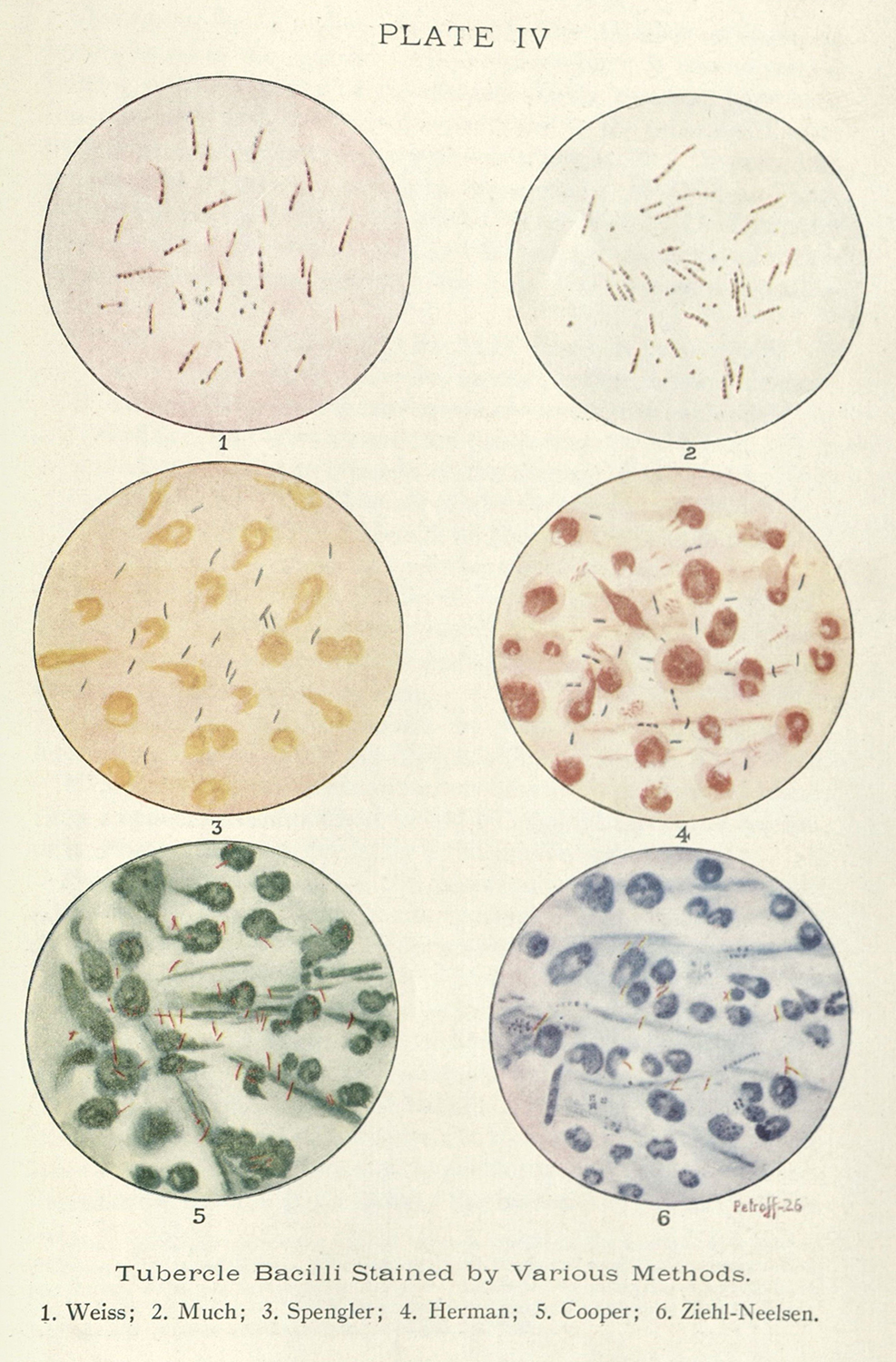

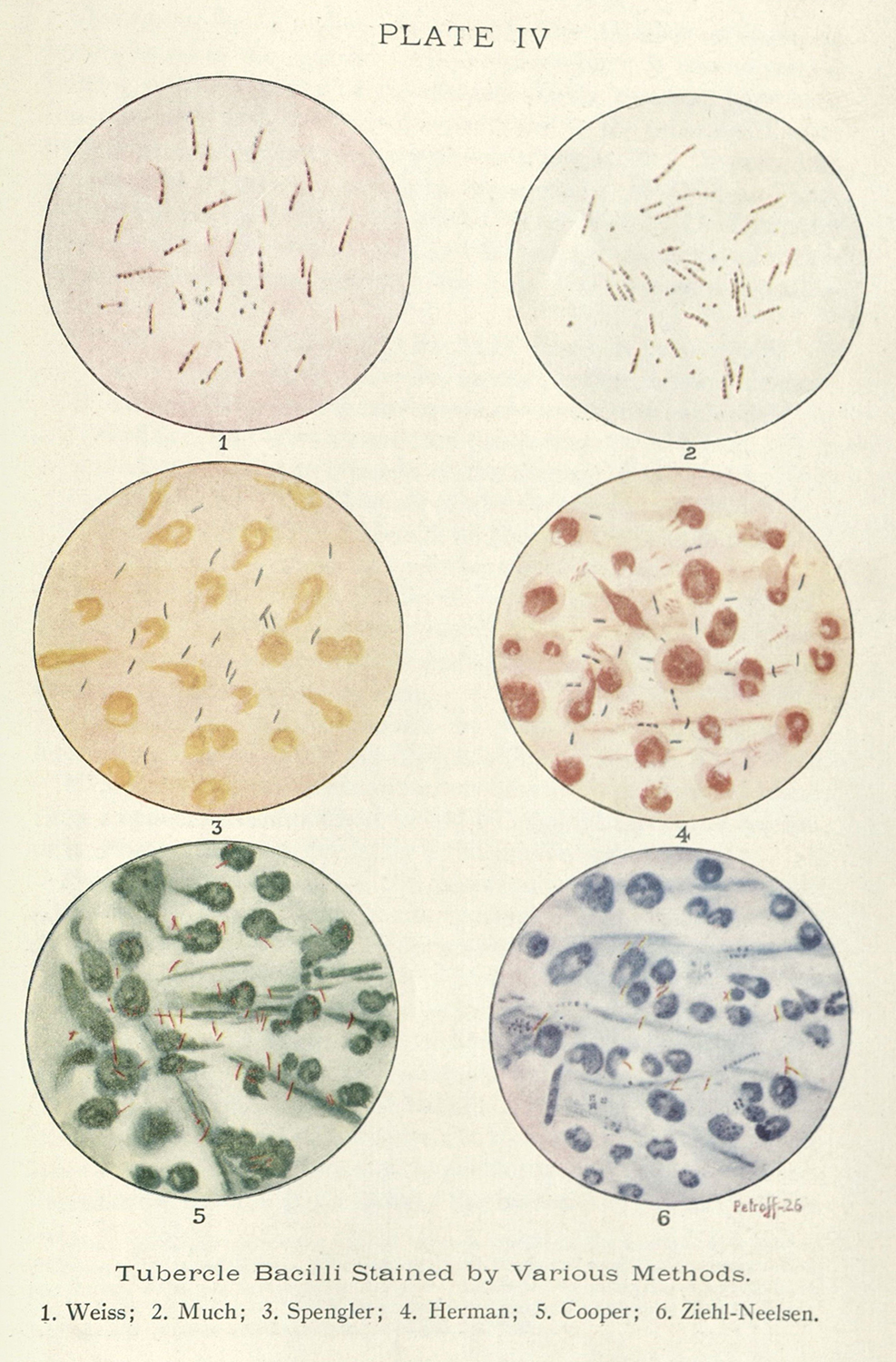

In the years following Koch’s research, a number of processes to dye tuberculosis bacteria would be developed, but there is a bit of fuzziness in my understanding of different methods to detect the germ in sputum (figs 14 & 15). Most of the case studies I have encountered discuss a positive or negative sputum test, which must be a microbial examination of the sputum, but I have not found a specific methodology in the books. (Part of the issue is a methodological one on my part: because I have been working with so many sources, it means that I have not had as much time to devote to investigating the books and journals one by one. My hope once the dissertation is complete to spend more time with those sources.)

Figure 14. : Edward R. Baldwin. Tuberculosis: Bacteriology, Pathology and Laboratory Diagnosis, with Sections on Immunology, Epidemiology, Prophylaxis and Experimental Therapy. (Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger, 1927).

Figure 15. Francis Troup. Sputum: Its Microscopy and Diagnostic and Prognostic Significations. (Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd,1886).

What I want to note here, before I move on, is that testing for Mycobacterium tuberculosis is a further abstraction of disease from the human subject. Jose van Djick and Katherine Waldby have each discussed an increasing fetishization around transparency in medical research and diagnostics, citing the x-ray and MRI, but I think this practice is a bit different: it is about focus, and specifically a shallow focus.

I use focus as a double meaning: first, I mean by the intensity of attention toward a single object, but I also mean it by the way we talk about depth of field in lens-based practices. The relationship of the lens angle, the size of the aperture, and the distance from an image object determines what is in focus and what is not, and what can be in focus for a given setup. If the depth of field is quite shallow, you can, while adjusting the focus, see each layer of a set of objects singularly without directly noticing its presence in the frame when not in focus. It is why a filmmaker could shoot a scene through a window screen, a chainlink fence, or use a pair of pantyhose over the lens to cut the light in a pinch. It is especially present when trying to focus with a microscope, as it too uses narrow angle lenses, allowing the viewer to slip between layers of visibility quite quickly depending on how thick an object might be.

What I want to stress here is that all of these actors—technological devices, chemicals, human scientists, and non-human organisms—are working together to produce a very specific result: the visualization of a microbe, and with it, the proof of a malady. I make this argument with a non-human organism, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, precisely because it helps me nuance clinical vision in a couple important ways. First, the technological, epistemic, and social shifts that follow the anatomical-clinical method nuance and change the ways disease is understood and diagnosed: clinical vision (at least in the historical examples provided by Foucault) had less space for a kind of outside, non-human entity. It relies on the relationship between subject, their supposedly aberrant symptom, and an idealized version of human anatomy. To look at a microbe is to look at something else, and while the practices are importantly similar,9 the technological, epistemic, and ideological apparatus that leads to these constructions of the human body and human health are distinct enough to deserve continued examination. Second, and what interests me most of all, is the shallow focus of this practice helpfully obscures particular relationships between subject and object.

This all brings me back to the term I am trying to articulate here: the pathological portrait. The notion of portraiture speaks to a singular object. For human portraiture, it can be a single subject, drawn in such a way as to describe and reproduce their presences (fig. 16). In the pathological portrait, the same care and attention is given to the embodied symptoms or biological occurrence which is foregrounded and reproduced (fig. 17 & 18). The only thing that is important for this genre of images is the mallady on display. This interest in singular object leads to a shallow focus in regards to how and what is depicted, usually to the point where the object is excised from its embodied, historical source.

Figure 16. Lawrason Brown. The Story of Clinical Pulmonary Tuberculosis.(Baltimore: The Williams & Wilkins Company, 1923.)

Figure 17.

Figure 18

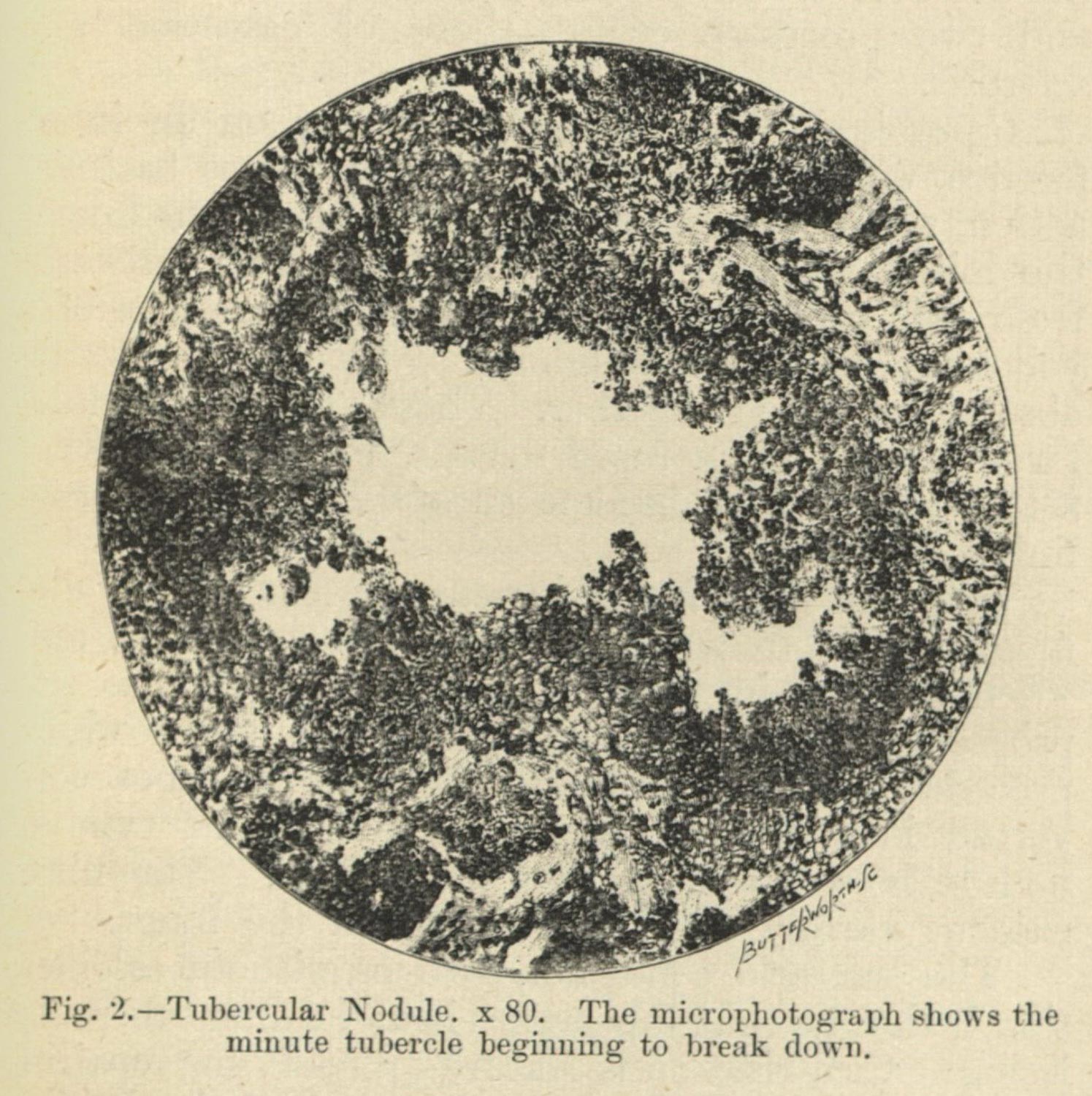

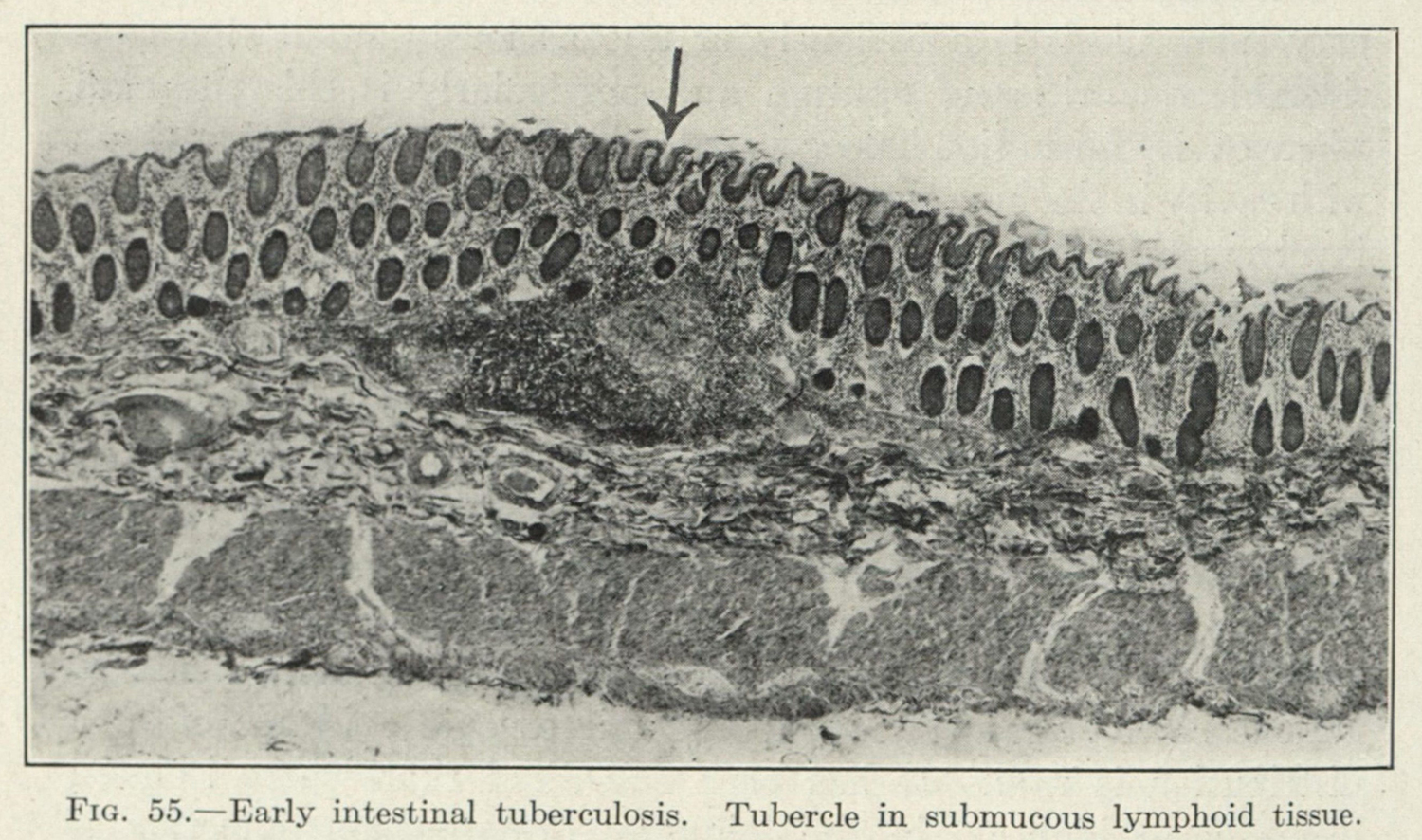

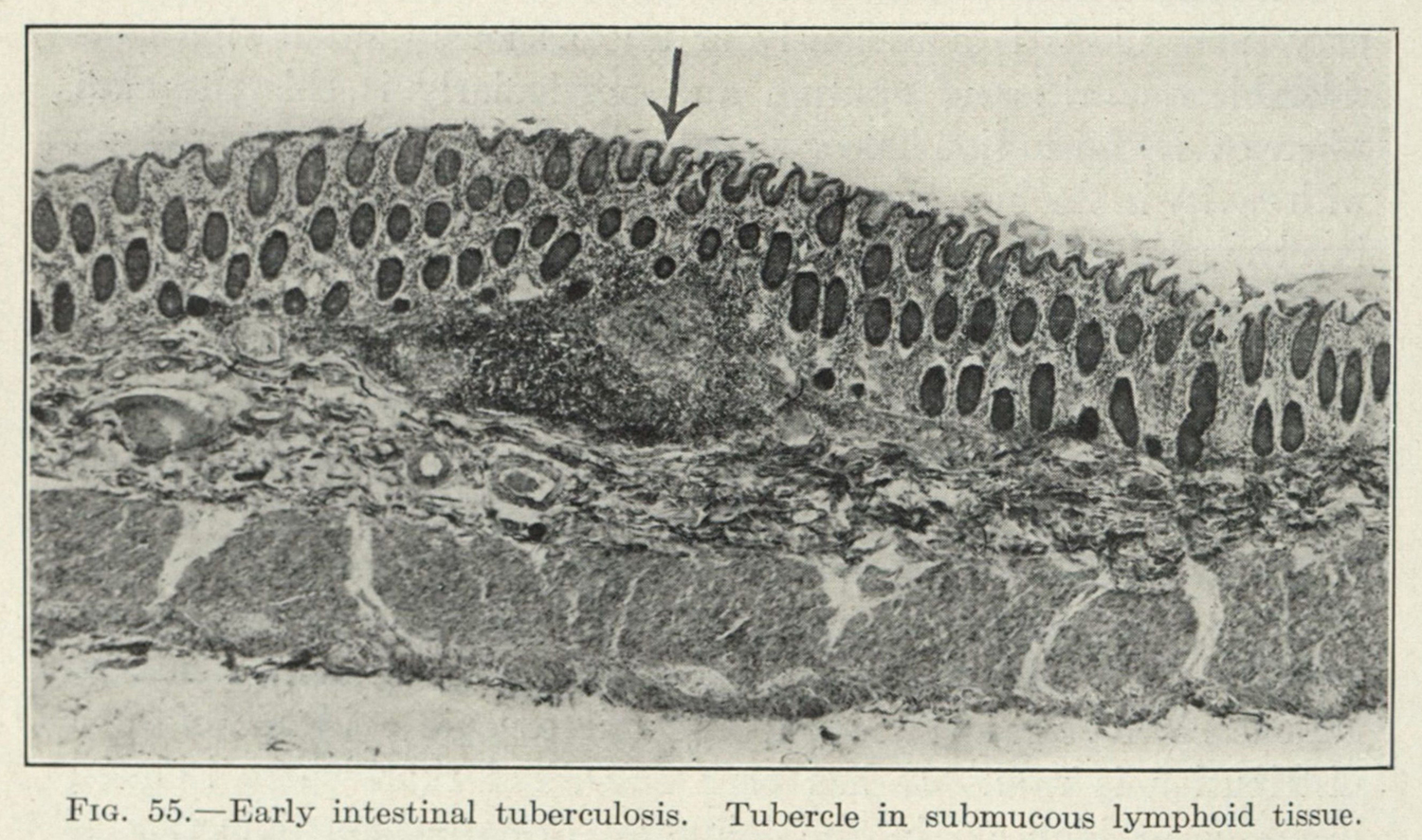

I am going to move a bit more quickly through a few images (which represent broader trends in the scientific literature around tuberculosis), to describe what I mean. First, I want to look at some representations made possible by microscopic vision (fig. 19).

Figure 19. From Edward R. Baldwin. Tuberculosis: Bacteriology, Pathology and Laboratory Diagnosis, with Sections on Immunology, Epidemiology, Prophylaxis and Experimental Therapy. (Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger, 1927).

Where Koch’s work and the other bacterial stains provided a shallow focus on the microbes themselves, these images fit closer into the clinical frame I’ve discussed at length. There is something quite obdurate and abstract about these representations, at least to someone who is not trained in microscopic vision or cellular anatomy, but there is something also very singular about them. The material which has been sectioned, framed, focused, and reproduced has been done so in a singular manner: to show some minute, cellular-scale effect of the microbe on the body. The singularity of vision forecloses the other relational aspects: what is next to the frame? what is one or two layers deeper or shallower? what about the rest of the organ, or the rest of the subject? Partially, this is a problem of scale—as we move deeper some objects will become more clear and others will become too complex to quantify in a single image or set of images—but it is also operates on an assumption that the object can be conceptually grokked into place in relation to all sorts of objects which are out of frame.

Moving outward, then, there is an entire genere of images which pertains to wet specimens reproduced to depict pathologies in those organs (figs. 20 & 21). Again, as a lay viewer, I am unsure where the healthy organ ends and where the pathology begins. Moreover, the organ, severed as it is from its anatomical context, brings a higher barrier to entry. It is striking to me, in relation to the anatomical texts of early modern and modern anatomists, that these images ignore the contextual and choose a singular approach to the object. The pathological portrait, as I am trying to articulate it, operates explicitly on this sequestering of the symptom; of alienating the organ from the body it originated from, and assuming that the information (tightly disciplined as it is)10 is more valuable because of its isolation. To savvy listeners, the kind of implicit isolation is the very practice which Bruno Latour describes in his monograph We have Never Been Modern: that by focusing on the non-political (that is non-human affected) ‘natural’ objects, it becomes impossible to see how deeply entwined those objects are to our cultures.11

Figure 20. Freeman Hall. Tuberculosis and Allied Diseases. (Kalamazoo: The Yonkerman Company, 1913).

Figure 21. August Jerome Larigau. Tuberculosis (Bacteriology, Pathology, and Etiology. (1900).

I am omitting a rather important aspect, which is to say that this way of looking is contextualized by written material, usually in the form of a case study. I do not have the time to address it in full today, and I have not been able to examine this relationship in detail (it will be addressed in a future dissertation chapter). My suspicion is that these case studies would be as varied as the approaches to imaging, but in my limited knowledge (framed by an interest in the reports by Lawrence F. Flick at the Henry Phipps Institute), there is a similar elision: to speak to symptoms and disease progression while omitting superflous elements.

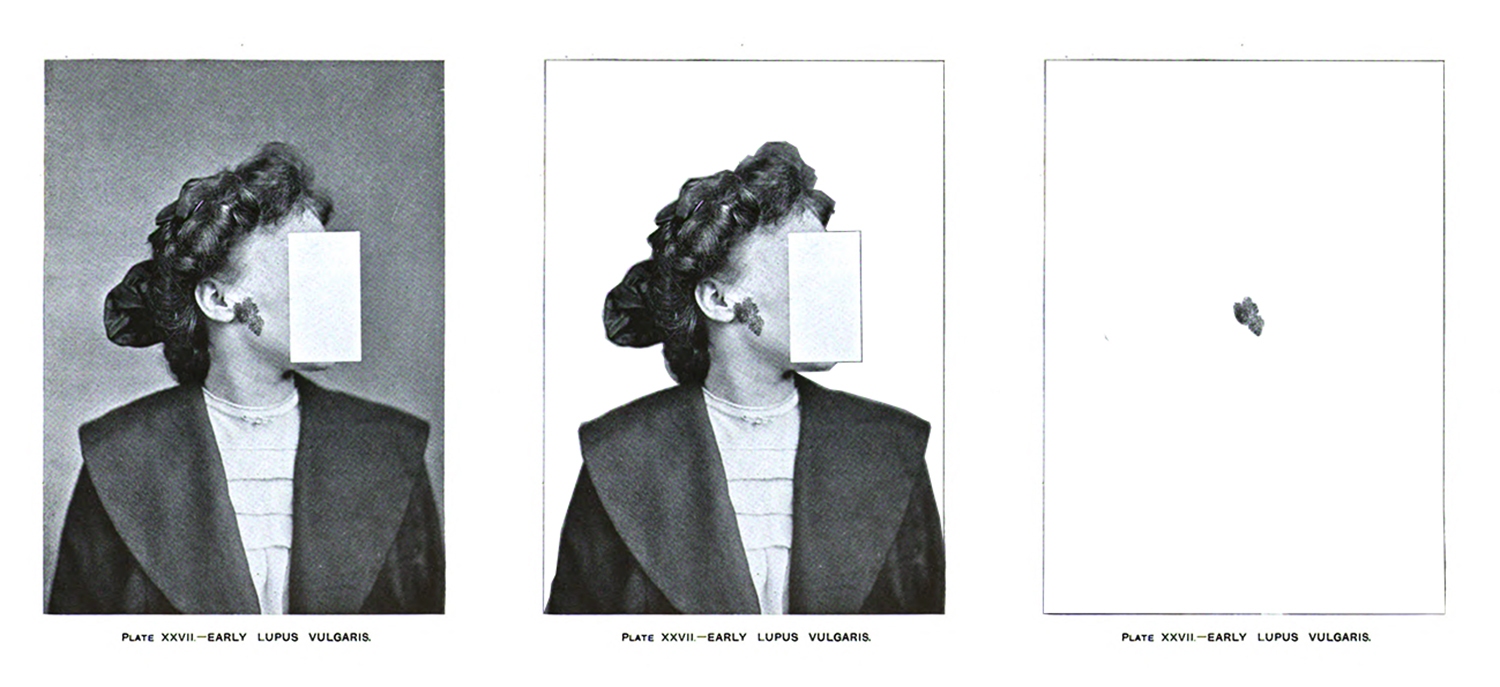

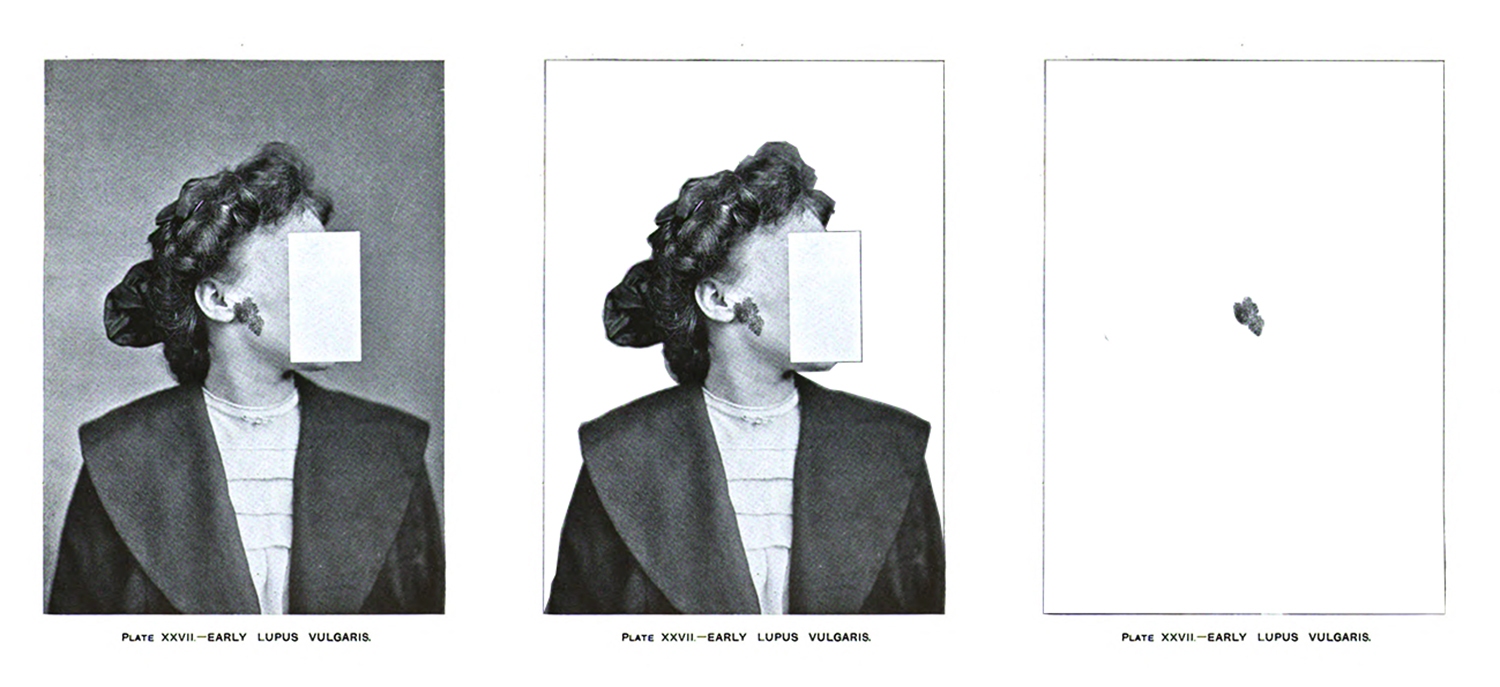

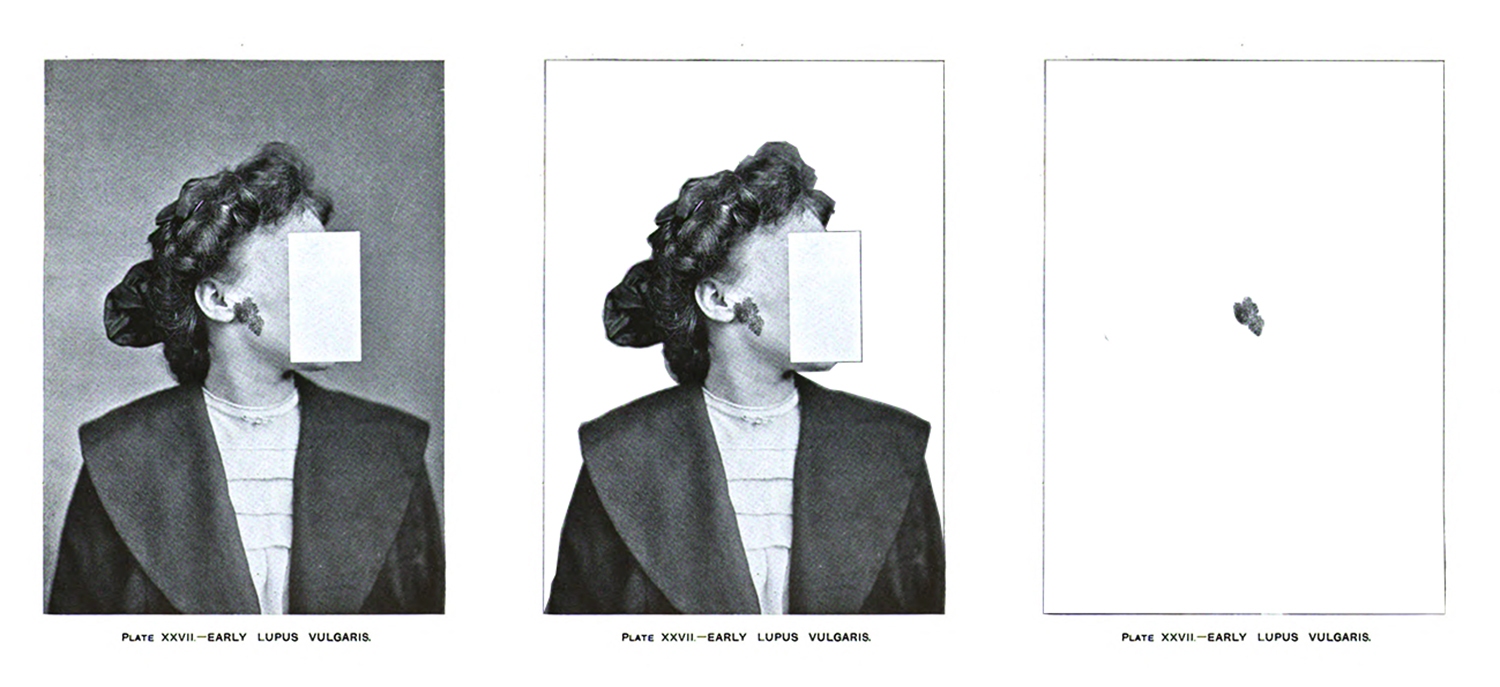

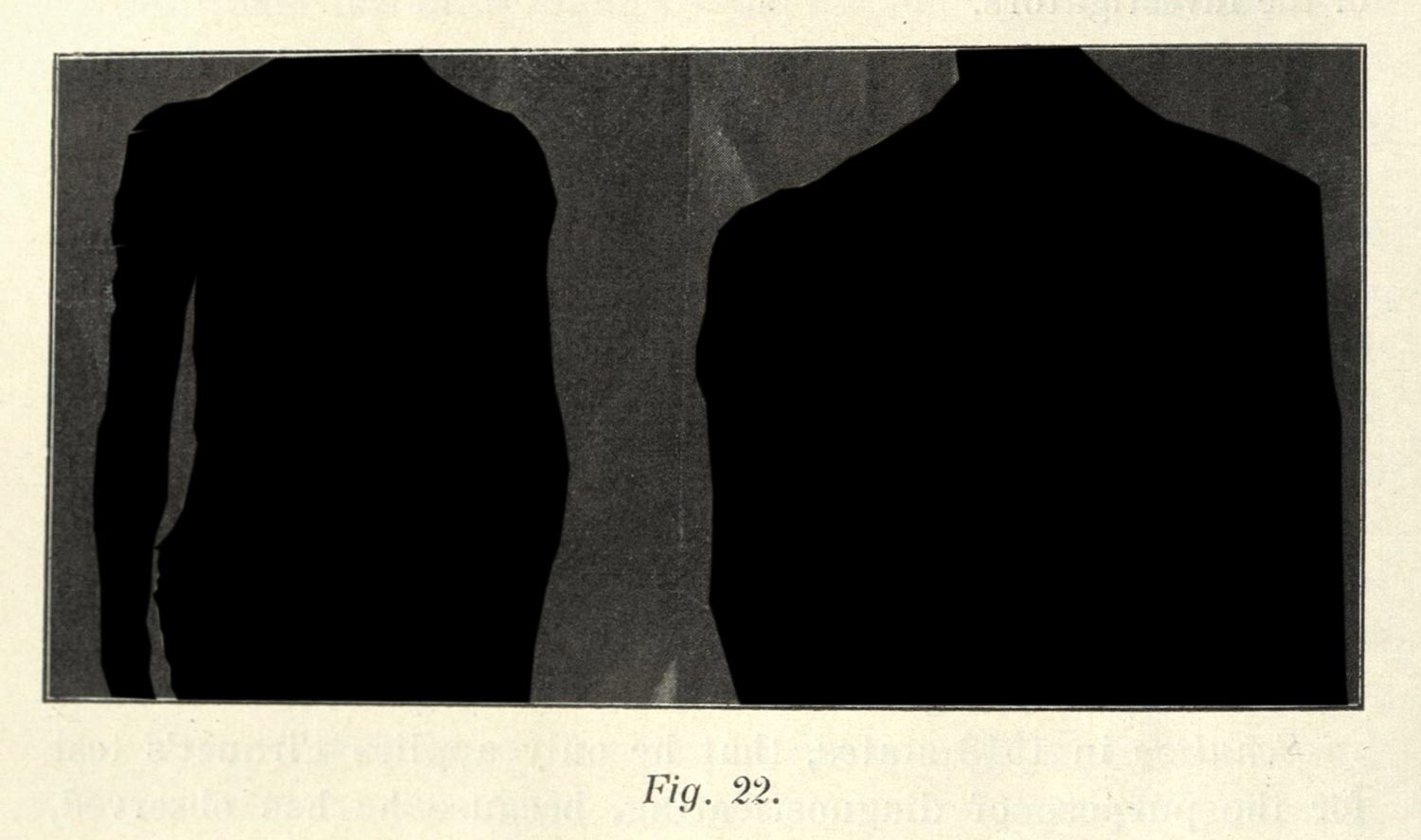

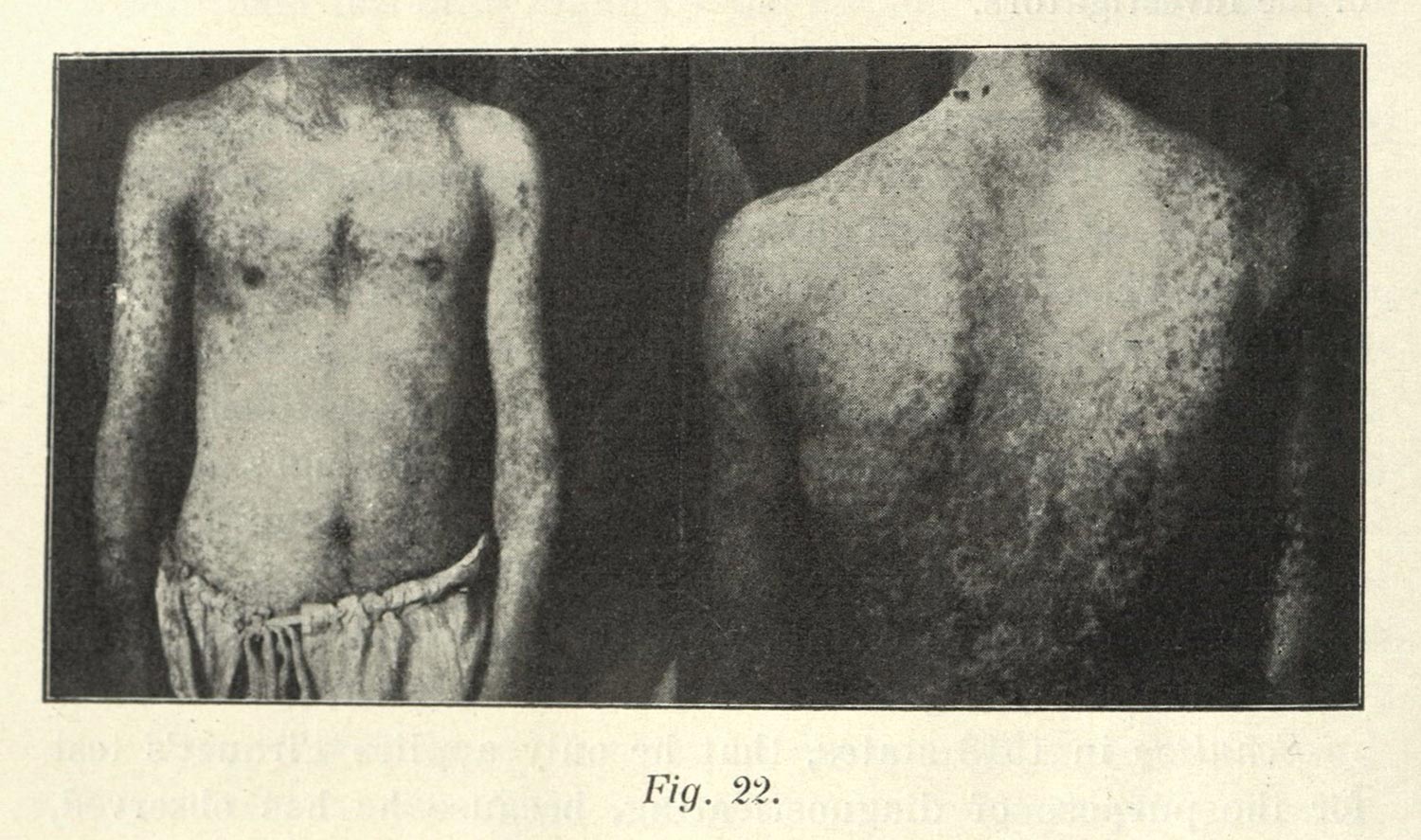

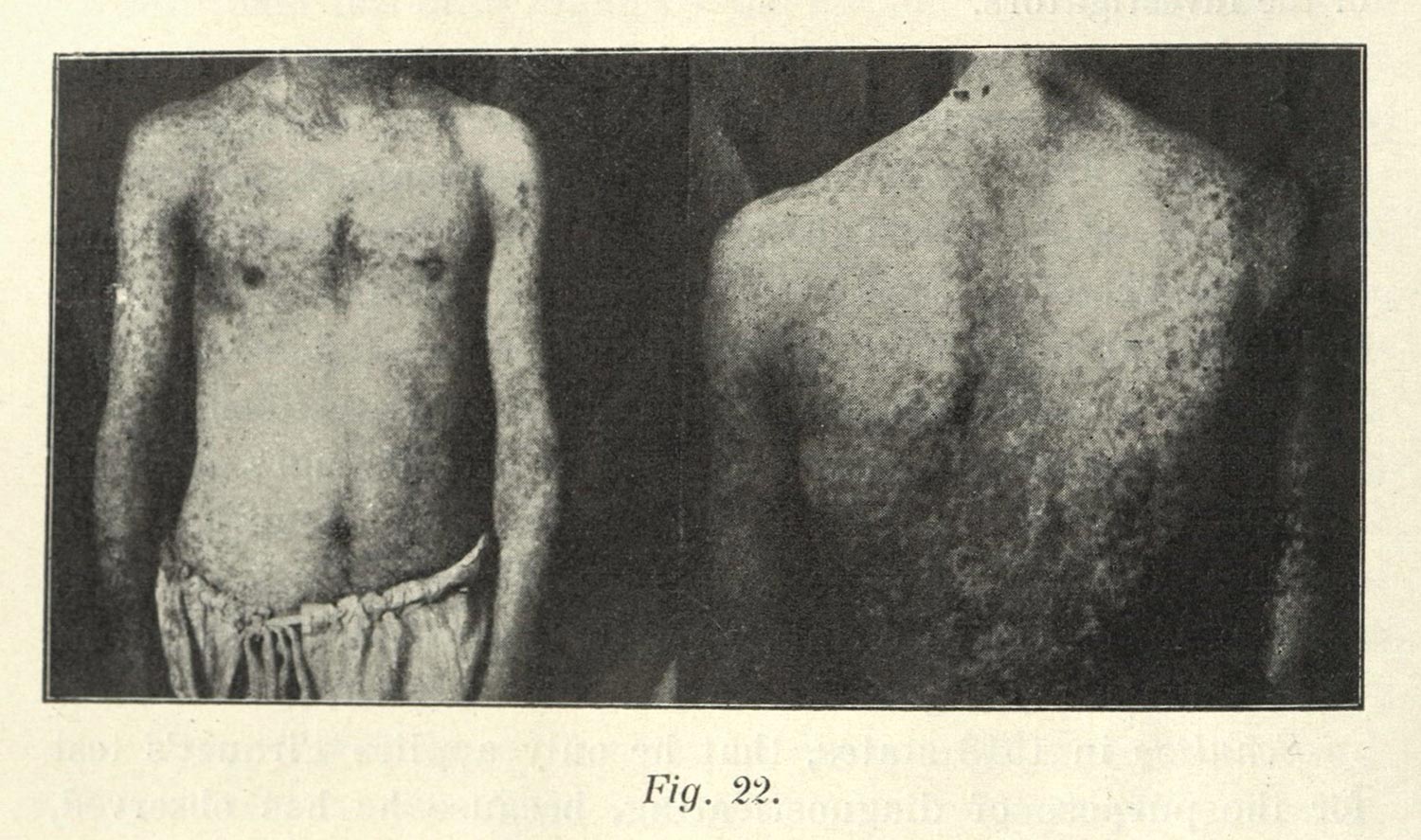

This brings me to a final thought in regards to these kinds of images, a kind of parallel approach to portraiture as it is depicted in dermatological atlases. I’ve written about dermatology before, and it was a series of images depicting lupus vulgaris (a skin condition caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis) that led me to my present study. And I want to use my previous work to briefly touch on an epistemic knot which I am continually trying to untie. The images of lupus vulgaris (which admittedly come from dermatologists and not germ theorists, lung researchers, or tuberculosis specialists) rely on a contextually in the image (fig. 22). Quoting my previous work, “Central to these discourses, of course, is not just the object in isolation, but [the object] in the context of the body and culture. In some cases, these images are utterly devoid of meaning without the body to inscribe onto or describe through, and in others, this is only made possible through a disciplining of the subject’s body to hold still long enough for proper exposure.”12

Figure 22. Malcom Morris. Diseases of the Skin: An Outline of the Principles and Practice of Dermatology. (New York: William Wood and Company, 1909) p. 482.

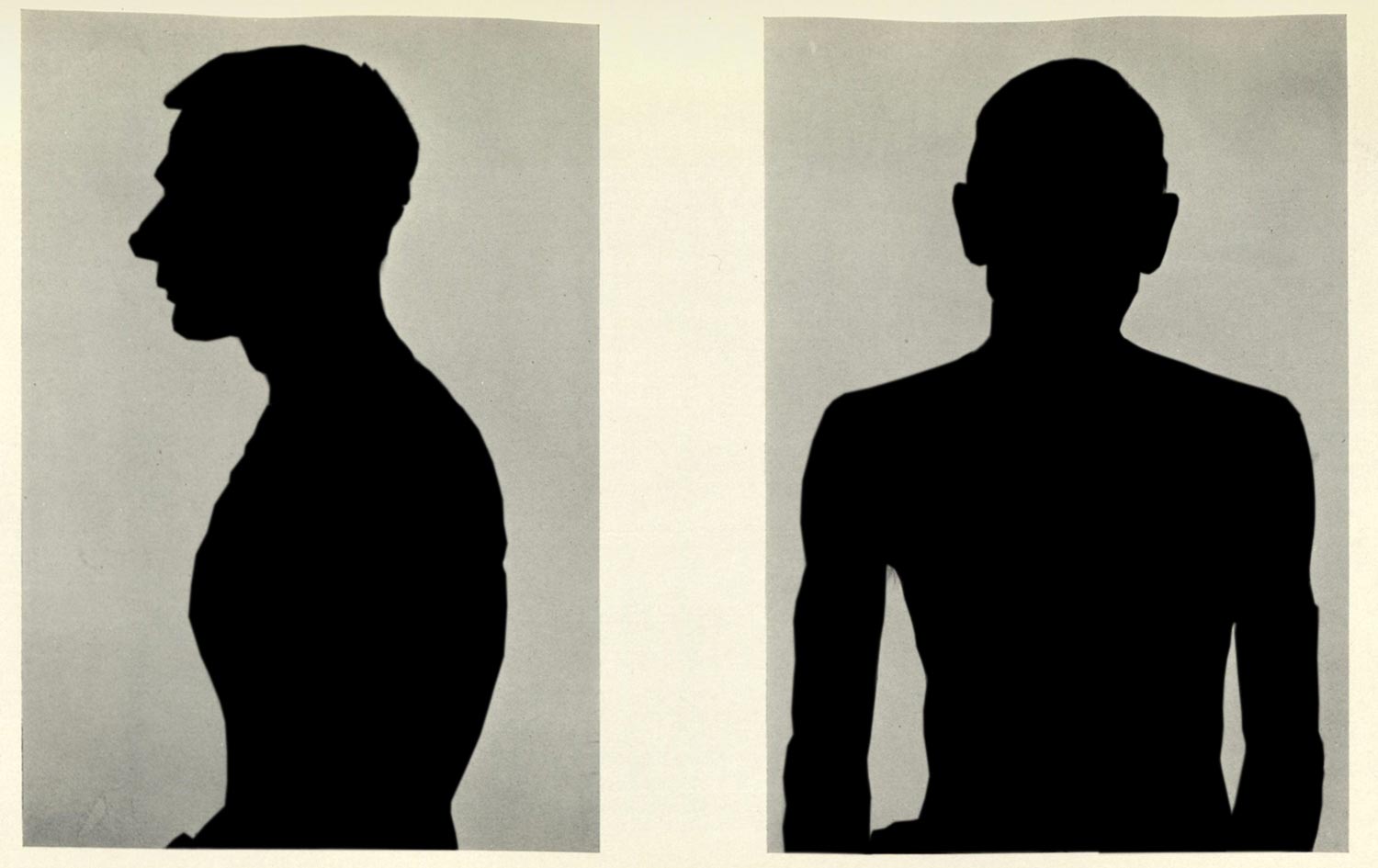

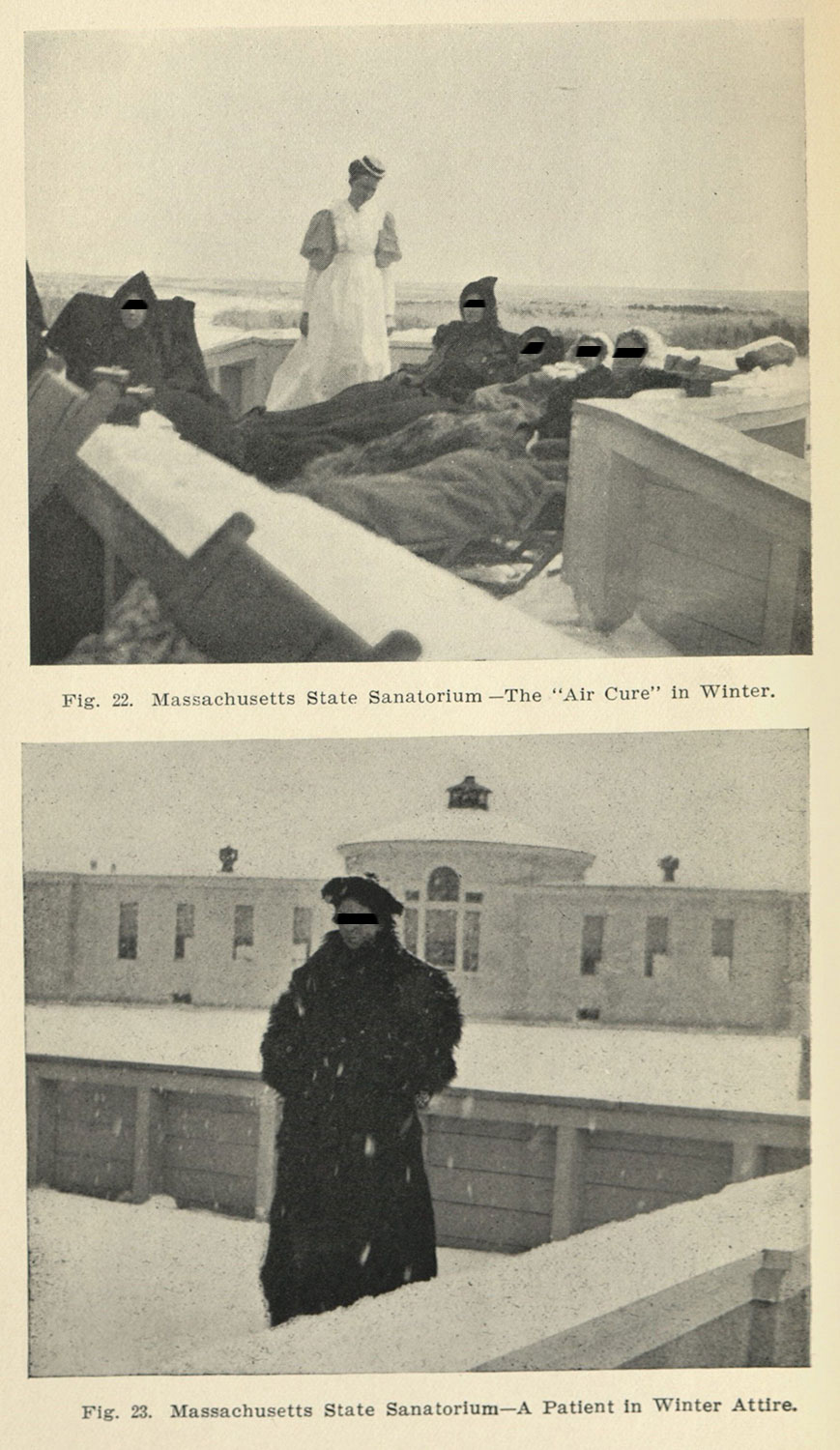

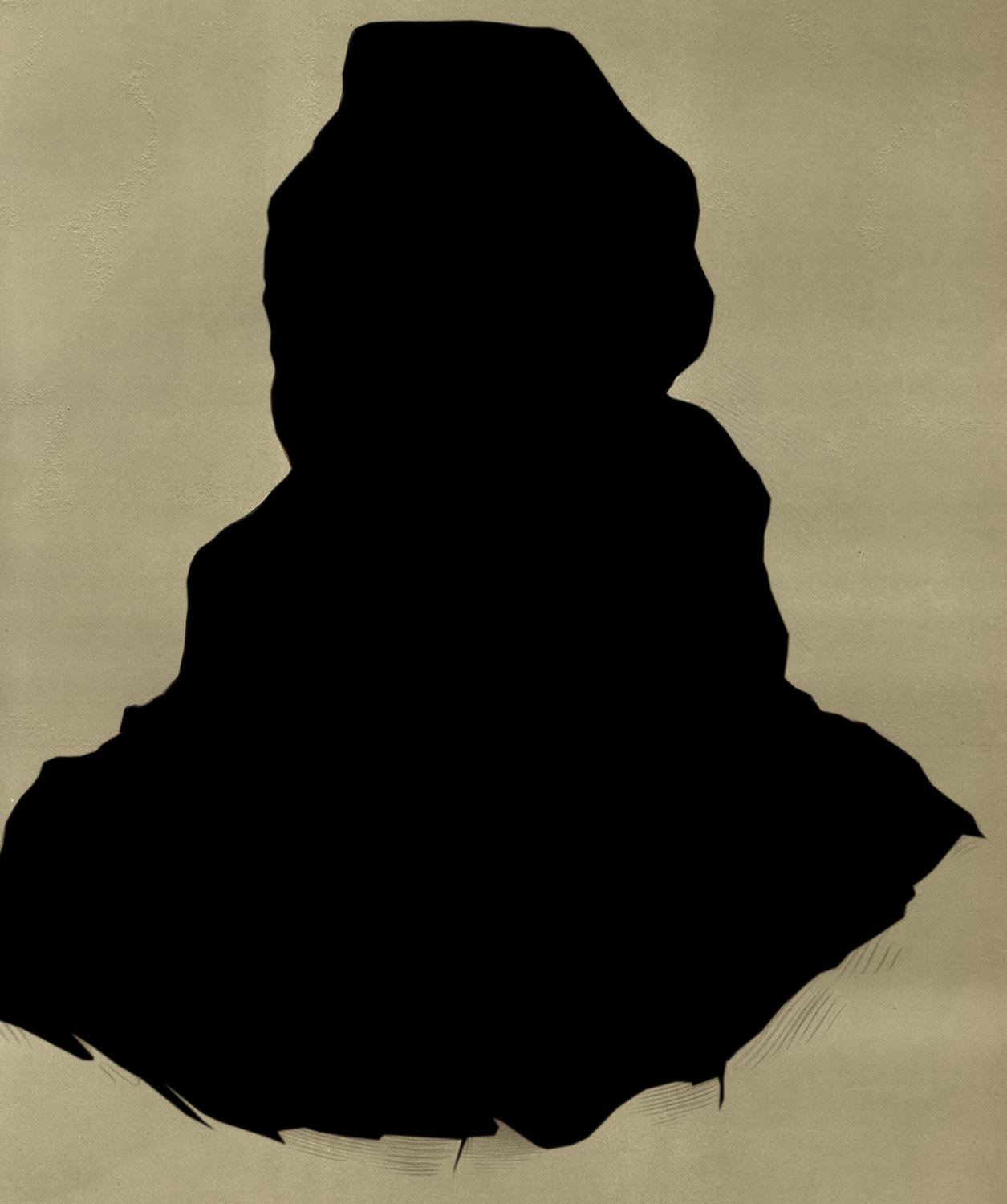

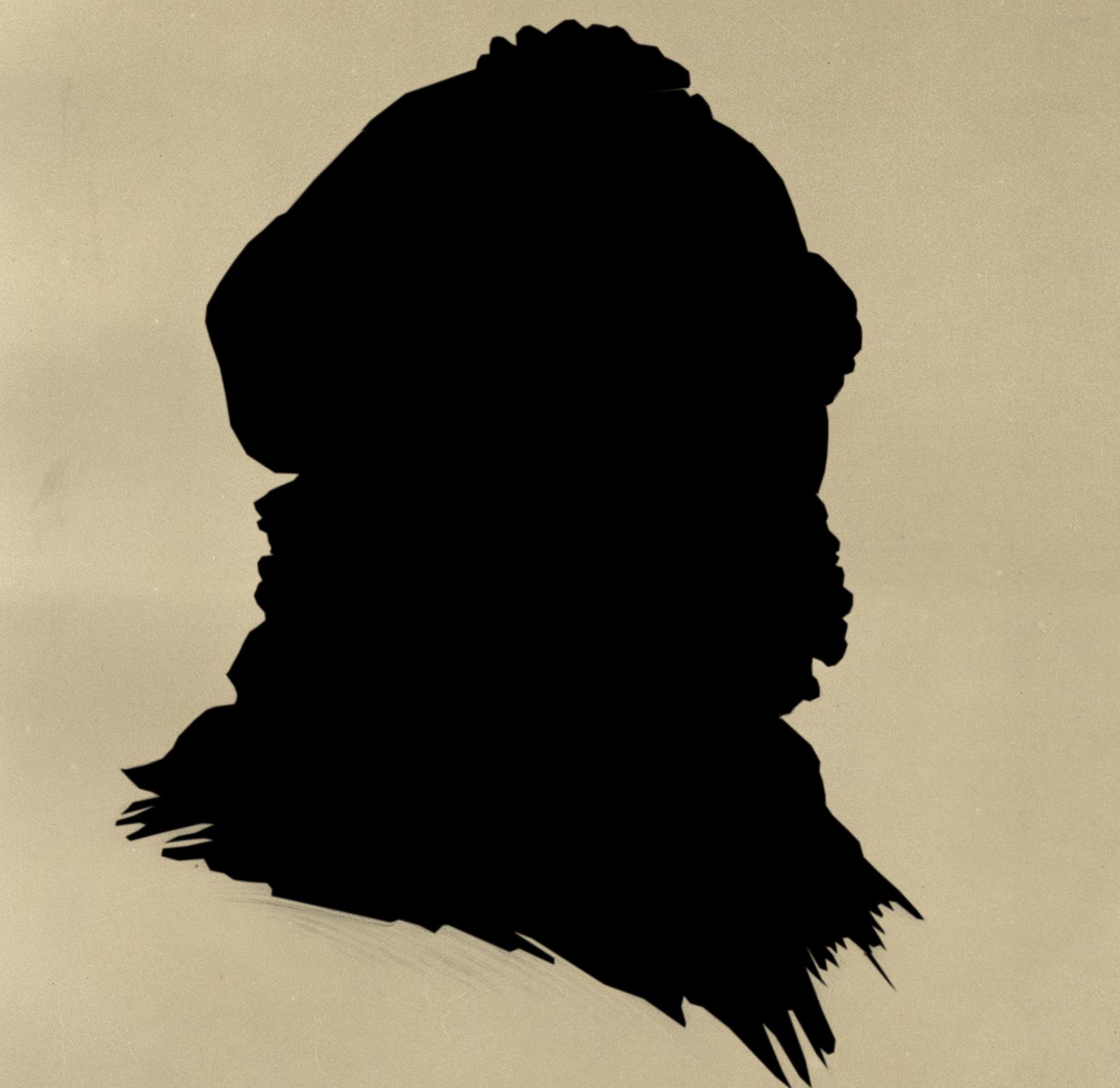

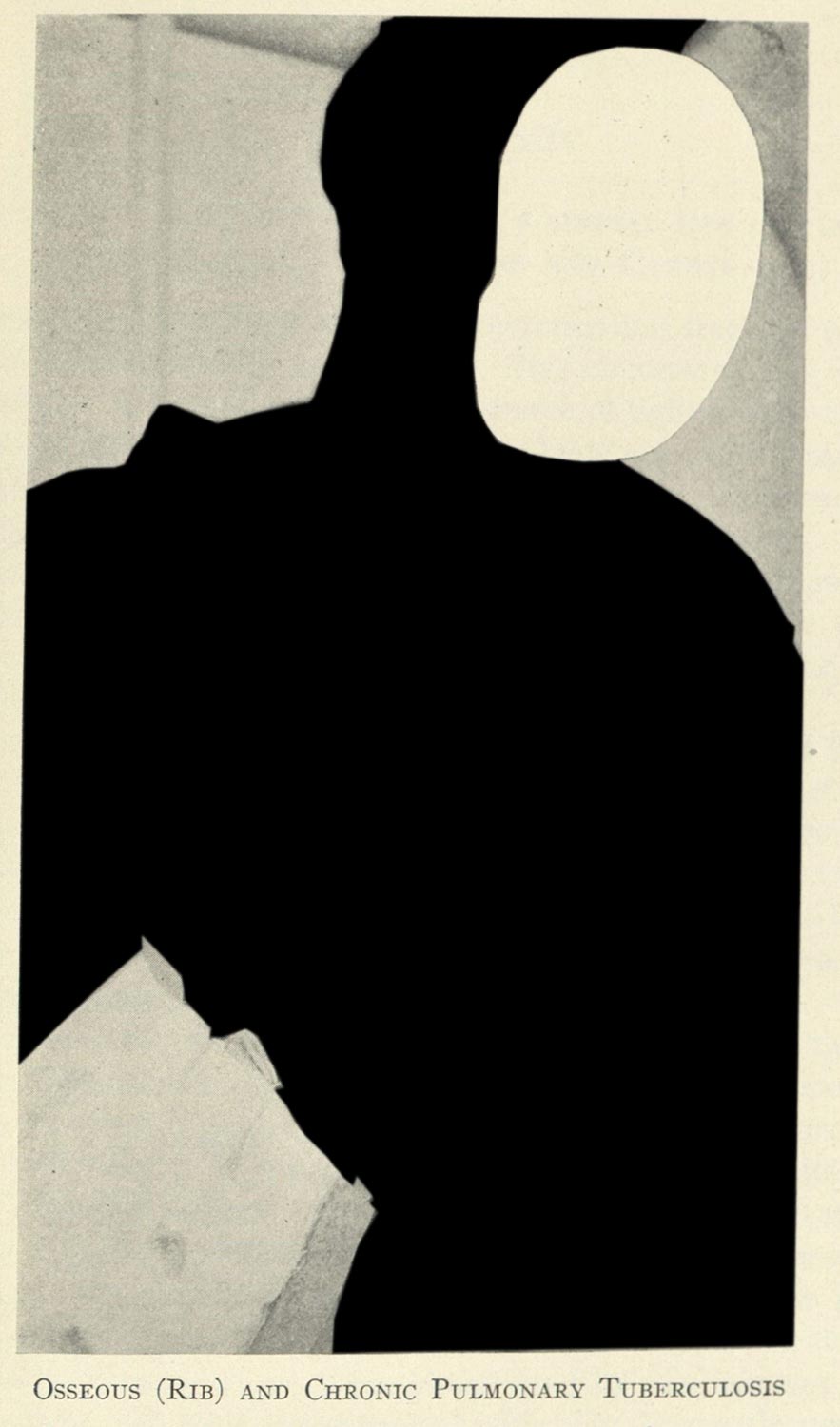

These images, which show enough of a body for context, strike me much more differently than the others I have shown. In the case of this older image by Ferdinand Ritter von Hebra, there is an implicit respect given to the sitting subject, even if the visual practices I have described might lead doctors to ignore the unique, singular human being from which the illustration was made (figs. 23 & 24). The curious thing, too, is that context drives these kinds of images, but at the same time some doctors frame and pose and cut their images in ways that respect (at least partially) the anonymity of the subject (figs. 25 & 26)

Figure 23.

Figure 24.

Figure 25. Edgar, Mayer. Clinical Application of Sunlight and Artificial Radiation: Including their Physiological and Experimental Aspects with Special Reference to Tuberculosis. (New York:The Williams & Wilkins Company, 1925).

Figure 26. Knud Secher. Treatment of Tuberculosis with Sanocrysin and Serum (Møllgaard). (Copenhagen: Levin & Munksgaard Publishers, 1924).

Opaque Methodologies

I end with these full body images to stress why understanding the shallow focus of the other images is so important, and also to point to an additional goal of my research. When I applied for the Helfand fellowship in Fall 2022, I had done so under the assumption that I would produce a museum-like exhibition; unfortunately, do to some institutional sluggishness at Indiana University, I had to put that project on hold. What I have begun to develop during this year, however, has been a similarly interested minimal computing project developing a platform and workflows for the ethical representation of human subjects in online exhibits, blogs, and dissertations. This platform is only possible with the research funds provided through the Helfand fellowship, as well as support provided by the Center for Research on Race Ethnicity and Society and the Institute for Digital Arts and Humanities at Indiana University (or IDAH). The website I am going to show you was developed as part of the Summer Incubator run by IDAH, and the hard work of a number of people, including Kalani Craig, Xavier Daniels, and Sagar Prabhu.

Central to this practice-based research13 is an emphasis on the continuity between the human subject and the biomedical specimen—that is any object extracted from a patient or human subject for biomedical research. One of the problems that the shallow focus on the organ, cell, or microbe affords is that it sequesters and compartmentalizes the phenomenon: it dehumanizes, and dehistoricizes it. Returning to the magnified cells I discussed earlier, there is a necessary link between the subject and this representation which cannot be reestablished. Whose cells are these? Did they consent to being imaged in this way? Did they know that they’d be dissected, their organs excised, photographed, displayed, reproduced, digitized, and then shown in the presentation today?

The patchwork of ethical standards prior to informed consent,14 the robust scholarship by historians of scientific racism,15 and the images themselves make me think that in many cases the subjects who are imaged would not have liked to be displayed as they were in the textbooks and journals of the period, let alone by some media studies student a century or more after their biomatter was collected. Shallow focus is a way for me to make sense of how a person can be pieced apart in the processes of scientific research, and it helps me retain and reclaim a continuity. The specimen always needs a subject; it always has a history; it depends on the extraction, exclusion, and isolation of its original index to stand in for a broader claim.

I often quote a line from Megan Rosenbloom’s Dark Archives, when I think about this problem. Writing about the history of Nazi medicine, and a book challenge to an anatomical atlas penned by a Nazi scientist in the interwar period, Rosenbloom discusses a necessary evil in the maintenance of the history of medicine. She writes, “if books have to be removed from a medical library because the bodies depicted in them were obtained through unethical and nonconsensual means, there might not be an anatomical text left on the shelf.”16 I think it is well known the malfeasance that undergirds the history of medicine, and it is something that unsettles me. It makes me uncomfortable, especially because my research, my professional career, also takes advantage of materials acquired from human subjects with dubious or nonexistent records of consent.

I want to finish with a moment of opacity. Opacity is a framework that comes from postcolonial scholarship: it is an ethic and practice that objects to the totalizing, essentializing acquisition of the colonized subject within western epistemics. Developed by Édouard Glissant, opacity is a mode of refusal, rejecting the ways western cultures produce value from the bodies, lives, and histories of othered subjects.17 My art practice engages with and expresses this refusal, and I have attempted to make opaque the history of medicine in my installations and photo essays. And I am attempting to the same thing with my dissertation, which is being developed for the web with opacity in mind.

I want to end with a link to this presentation, written in a prototype page for the dissertation. I hope that it can display what I mean, and the practice which I am forwarding. The digital platform will provide workflows, guidance, and code which Kalani Craig and I are developing specifically for opaque digital exhibits, dissertations, blogs, and collections.

Part of these workflows is to develop a platform that is informed by the work of Indigenous archivist and digital humanist Kimberly Christen and her platform Mukurtu,18 with a minimal computing philosophy. Part of it is also make quite literal the connection between human subject and medical image: to stress how much these objects depend on the subjects from which they are drawn. And finally it is to practice and explore what the history of medicine might look like if we were to extend to the historical subjects whose lives and afterlives are caught in the primary sources of the history medicine the same kinds of respect we afford contemporary research subjects.

Thank you.

-

Foucault, Michel. The Birth of the Clinic: An Archeology of Medical Perception. Translated by A. M. Sheridan Smith. New York: Vintage Books, 1994. ↩

-

O’Connor, Erin. “Camera Medica.” History of Photography 23, no. 3 (1999): 232–44. ↩

-

Rawling, Katherine D. B. “‘She Sits All Day in the Attitude Depicted in the Photo’: Photography and the Psychiatric Patient in the Late Nineteenth Century.” Medical Humanities 43, no. 2 (2017): 99–110. ↩

-

Charles E. Atkinson. Lessons on Tuberculosis and Consumption for the Household. (New York & London: Funk & Wagnalls Company, 1922). ↩

-

See: Sontag, Susan. Illness as Metaphor and AIDS and Its Metaphors. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1990. ↩

-

Some of this has been addressed by Scott Curtis.

Curtis, Scott. “Photography and Medical Observation.” In The Educated Eye, edited by Nancy Anderson and Michael R. Dietrich, 68–93. Hanover: Dartmoth College Press, 2016. ↩

-

Bracegirdle, Brian. “J. J. Lister and the Establishment of Histology.” Medical History 21 (1977): 187–91. ↩

-

Bennett, J. A. “The Social History of the Microscope.” Journal of Microscopy 155, no. 3 (1989): 267–80; Bracegirdle, Brian. “The History of Histology: A Brief Survey of Sources.” History of Science 15 (1977): 77–101; Gooday, Grame. “‘Nature’ in the Laboratory: Domestication and Discipline with the Microscope in Victorian Life Science.” The British Journal for the History of Science 24, no. 3 (1991): 307–41. ↩

-

in media studies we could consider these in an archaeological sense as being interlinked and dependent, but not determined. Add some media studies stuff. ↩

-

Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. New York: Vintage Books, 1995. ↩

-

Latour, Bruno. We Have Never Been Modern. Translated by Catherine Porter. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1993. ↩

-

Purcell, Sean. “Dermographic Opacities.” Epoiesen, 2022. http://dx.doi.org/10.22215/epoiesen/2022.1. ↩

-

Willis, Holly. Fast Forward: The Future(s) of the Cinematic Arts. London & New York: Wallflower Press, 2016; Burdick, Anne, Johanna Drucker, Peter Luenfeld, and Todd Presner. Digital_Humanities. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2012. ↩

-

Lederer, Susan. Subjected to Science: Human Experimentation in America before the Second World War. Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995. ↩

-

Washington, Harriet A. Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present. New York: Harlem Moon & Broadway Books, 2006; Willoughby, Christopher D. E. Masters of Health: Racial Science and Slavery in U.S. Medical Schools. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2022. ↩

-

Rosenbloom, Megan. Dark Archives: A Librarian’s Investigation into the Science and History of Books Bound in Human Skin. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2020. ↩

-

Glissant, Édouard. Poetics of Relation. Translated by Betsy Wing. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1997. ↩

-

Christen, Kimberly. “Does Information Really Want to Be Free?: Indigenous Knowledge Systems and the Question of Openness.” International Journal of Communication 6 (2012): 2870–93; Christen, Kimberly. “Gone Digital: Aboriginal Remix and the Cultural Commons.” International Journal of Cultural Property 12 (2005): 315–45. ↩