Chapter 4

Section 4.0

Section 4.1

Section 4.2

Section 4.3

Reflecting on the Terminal Imaginaries installation, I can concede multiple errors of scope. The production of this installation was driven by an interest to 1) learn more about medicine’s visual culture, 2) build on an interest in dermatology, 3) learn how to make a spatial video installation, and 4) to build in a public facing component. Some of these asks were framed by certain funding expectations,1 while others were personal desires.

I wanted to learn video art, in a desire to move away from my more traditional training in film and television production. I wanted to use an art project to get a better sense of a prospective dissertation project, which I knew had something to do with medicine, but which lacked definition. As with many emerging scholars at the phase between their qualifying exams and the prospectus, I was still trying to define a specific research object.

These scoping problems are common, especially for large-scale projects in and adjacent to the digital humanities.2 Terminal Imaginaries, while overtly broad, helped me narrow the project from addressing the entire field of medicine circa 1900 to a few specific interests. These were articulated in dissonance and harmony to one other through the installations overlapping projectors (fig. 1): one looked at anatomy, another looked at dermatology, and the other looked at doctor’s portraits. Each projector spoke to an interest (either explicitly stated on the project’s website, or found through reflection). Projector B, for example, reflected on the visual repercussions of the extractive epistemics so common to the biomedical sciences.3

Figure 2. The setup for the install as it was presented in spring 2021.

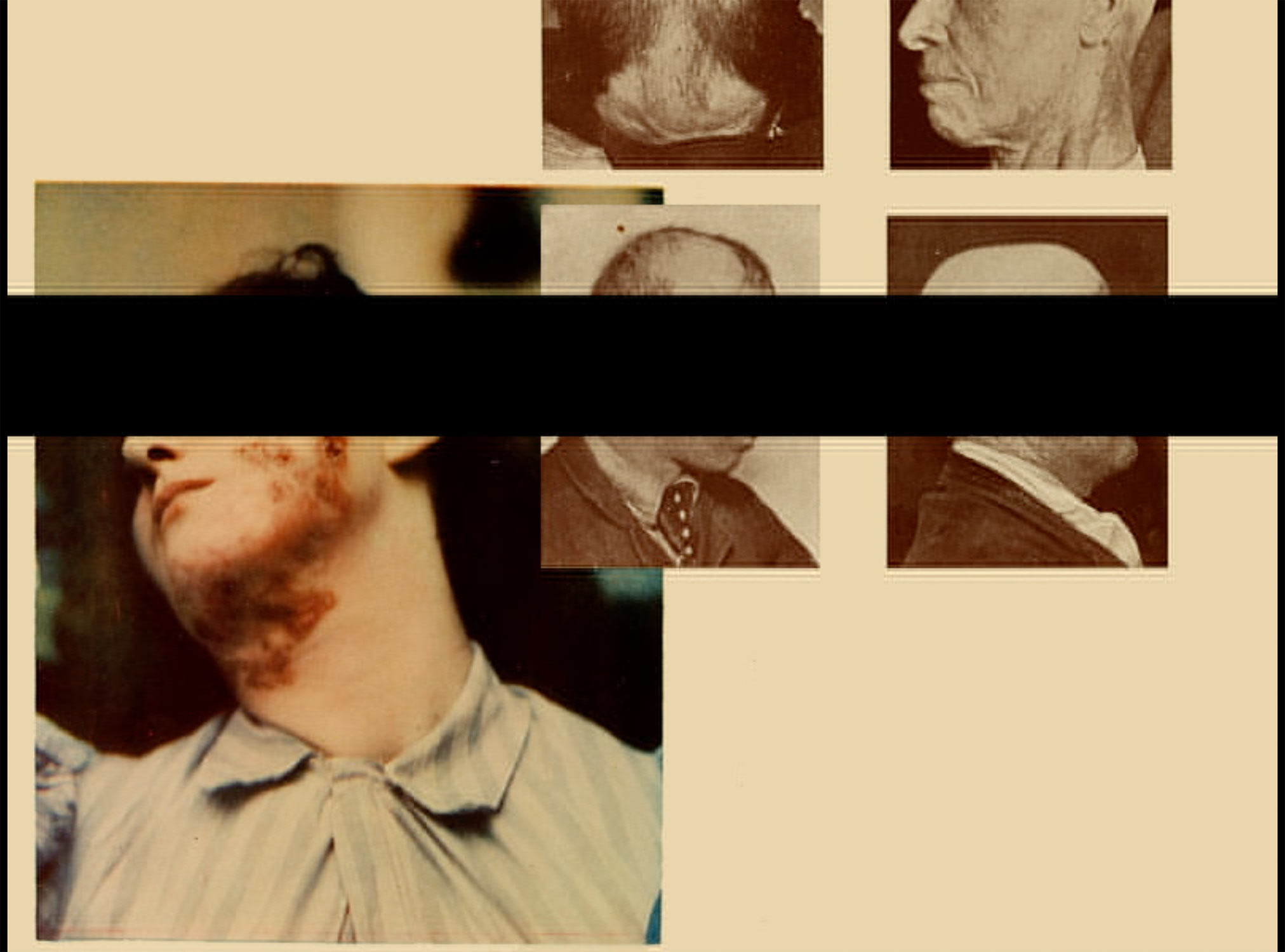

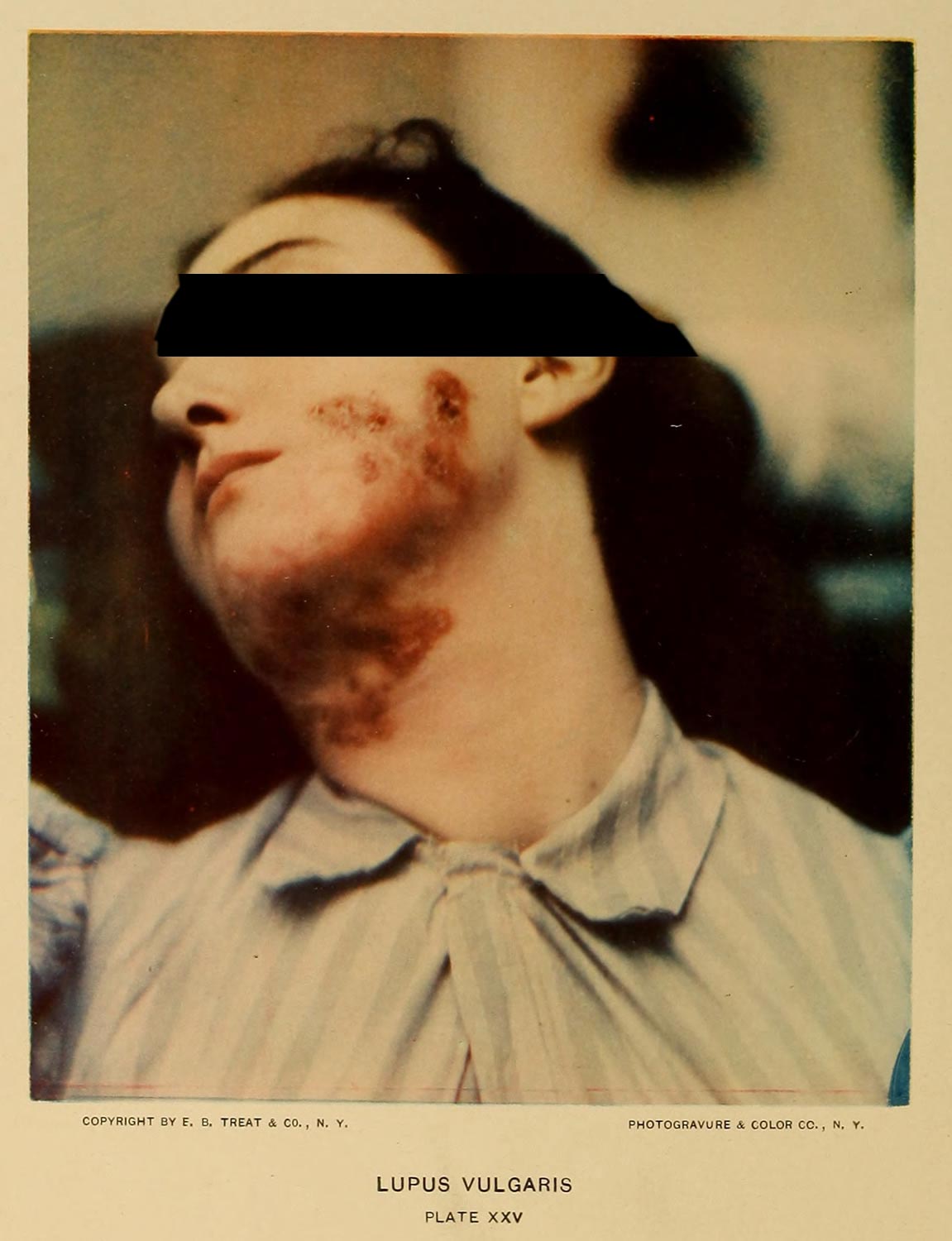

The overlap between projectors A and B (fig. 1) created an opportunity to think about the juxtaposition of the two image types. The kinds of dermatological images shown through projector A has a series of nested relationships with the anatomical, illustrative image of projector B. I had wanted to include some physical barriers between the projector and the screen, wanting a kind of physicality of the screen that seems so much a immaterial thing.4 What I realized, save for the mirror which cuts and recasts projector C, is that the physical implement did less to cut the light so much as order the space. Adding the black bar across the eyes of dermatological portraits (fig. 3 & 4) in the editing platform produced the desired effect without the finicky, too light, and poorly constructed (by me) flags.

Figure 3. A still from the video feed of Projector A. The images are arranged, cropped, and cut in particular ways to mimic a kind of false anonymity.

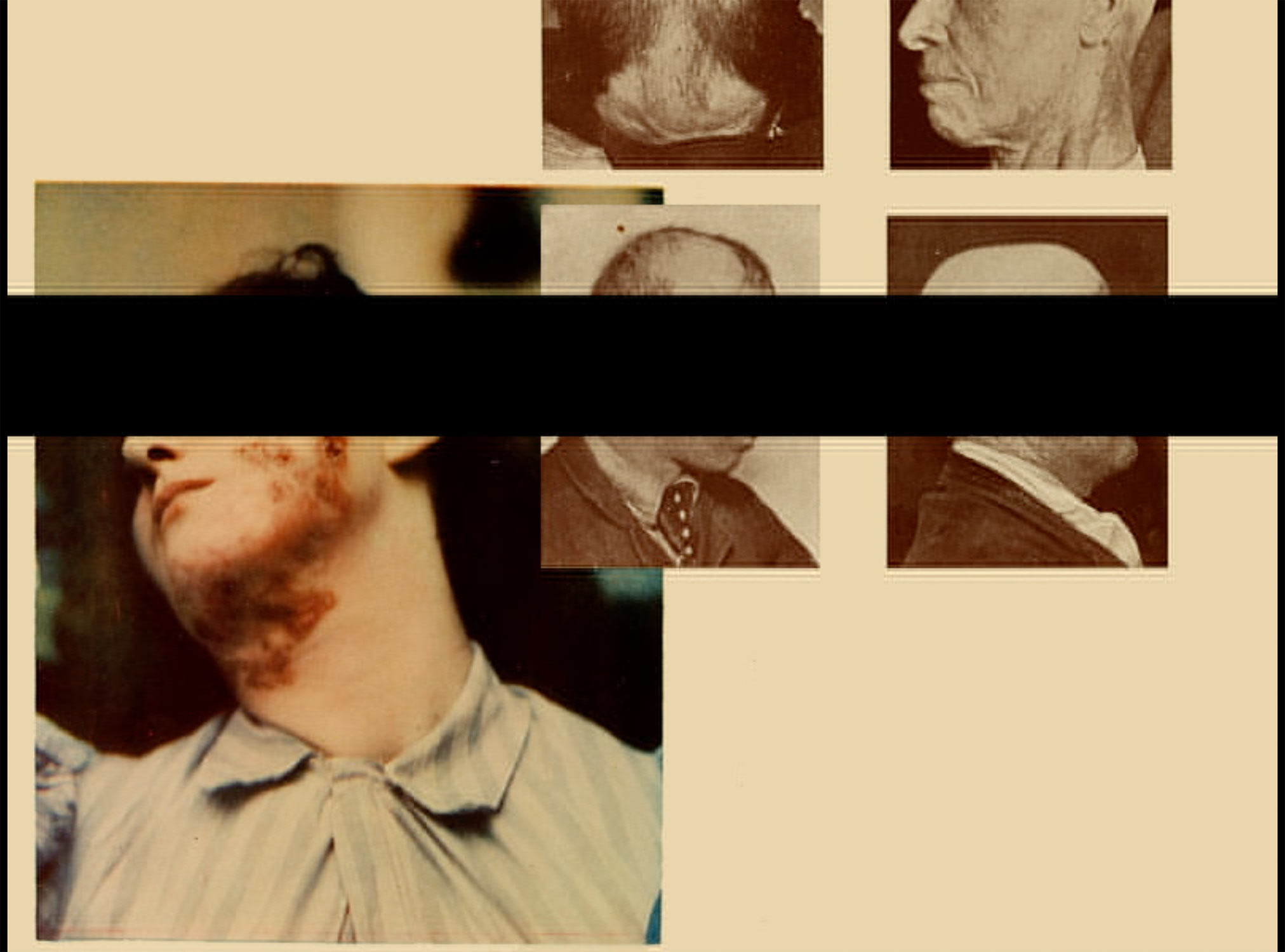

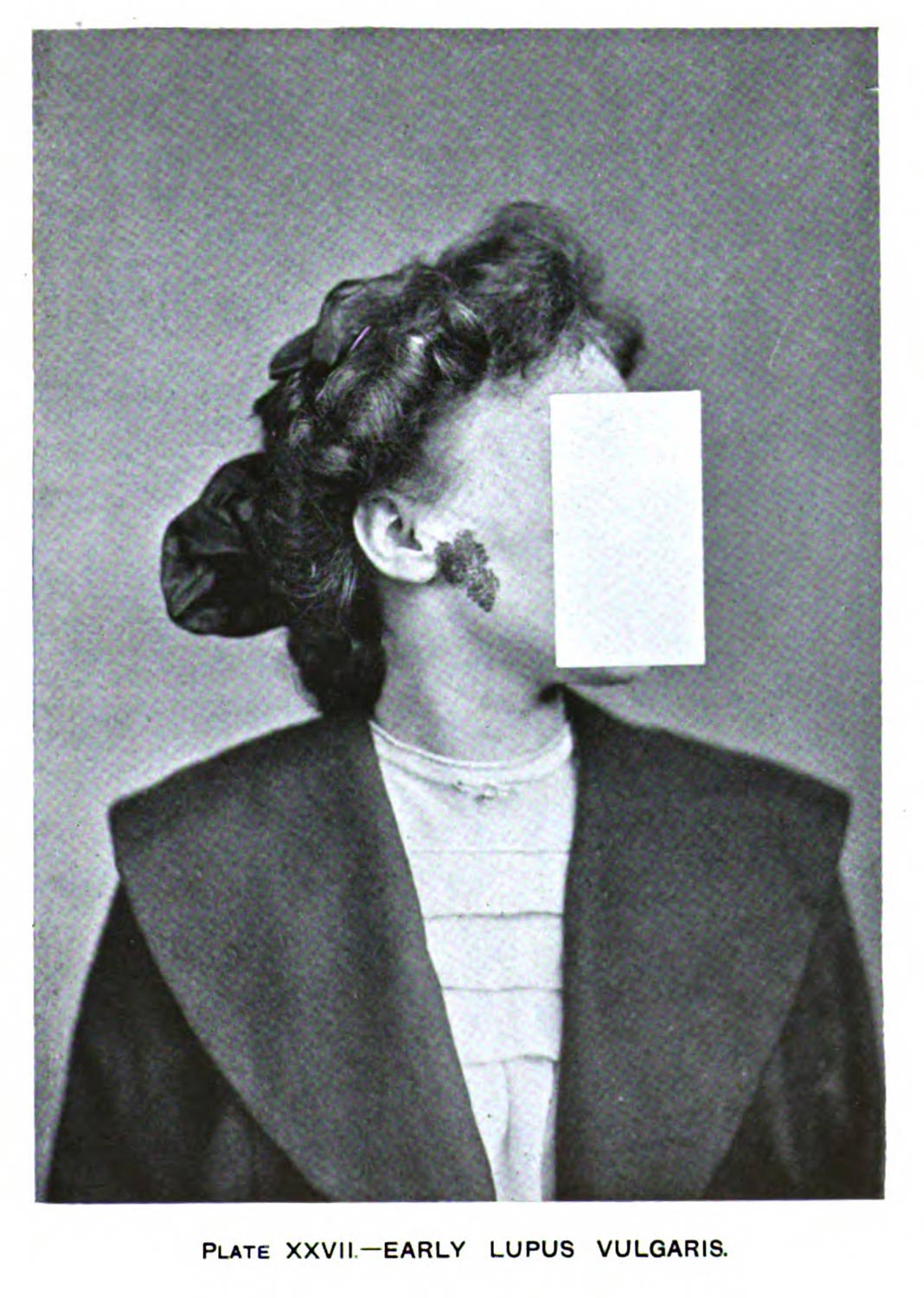

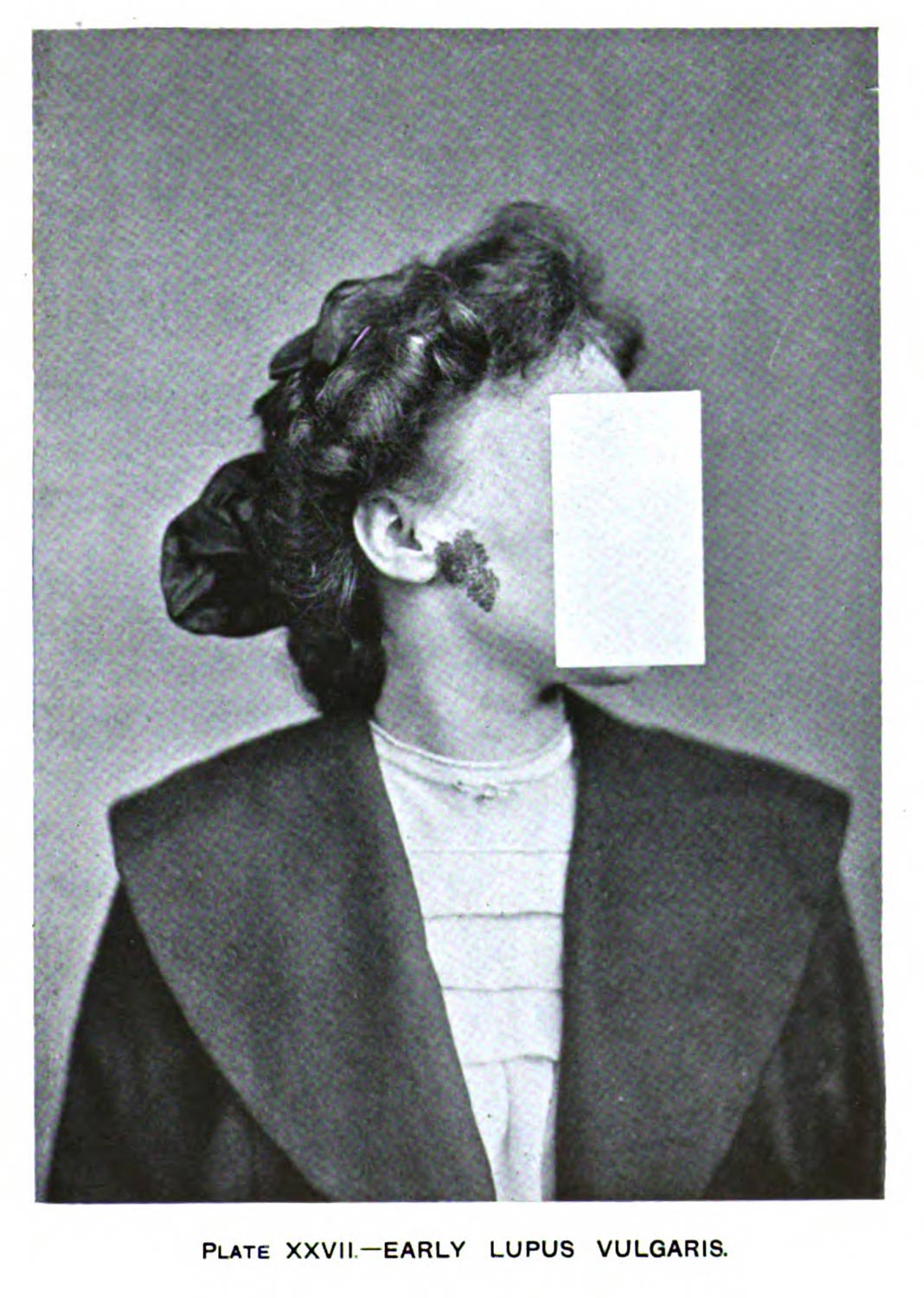

I had begun to think about this cut at the eye in the way the unnamed narrator in Chris Marker’s Sans Soleil talked about censorship. In the English translation of the quasi-documentary-travelogue, the narrator argues, over images of Japanese television that edit out nudity, that, “[c]ensorship is not the mutilation of the show, it is the show. The code is the message. It points to the absolute by hiding it.”5 In the context of the film, the narrator, speaking through and about a semi-fictional filmmaker modelled after Marker, is thinking about the televisual image, and the ways it has its own kind of language. For my own work, I think this censorship as a critical praxis, a means to subvert the image and use my own intervention to draw to the very thing that made me so uncomfortable: as a twenty-first century viewer, the doctors never seemed to care as to the personhood of their subjects. When they did offer some anonymity, as with the woman with lupus vulgaris who haunts the pages of this project (figs. 5), it some how made my ethical concerns more concrete. Why give one subject the privilege of anonymity, when another seems so obviously disempowered by the clinician (figs. 6 & 7)?

Figure 5. A dermatological photograph of lupus vulgaris. The patient that this pathological condition is manifested on has been given a kind of anonymity through the removal of her face from the frame. [!!!ADDCITATION]

Figure 6. [!!!Addtext].

Figure 7. An example from Gottheil’s [!!!ADDCITATION] where the subject is not afforded anonymity. [!!!ADDCITATION]

In the three years since I completed Terminal Imaginaries, I have read work that complicates the assumptions I made. In some cases, patients may have had some agency about whether their bodies were put to film.6 As I will negotiate in the next section (4.2.3), the broad critique in this project brings with it a set of problems which weakens the piece and the scholarship associated with it. What is important, for the through line I am trying to articulate, is a concerted effort in the removal of data as a means to point to and make explicit the systemic, aesthetic violence that permeates the object. In a moment of increasingly open data, in the egregious flush of access, conscious erasure (what I will begin to articulate more clearly as opacity) is a critical praxis. It creates friction against dominant epistemic ideologies,7 and produces ways of understanding the past which an open analysis would have more difficulty articulating.

-

Terminal Imaginaries was made possible through funding by Indiana University’s Institute for Digital Arts and Humanities and College Arts and Humanities Institute. As part of these grant applications, I was expected to produce something that interlinked arts practices and digital humanities practices. While I suspect that I did not have to do all of what I proposed, I felt obligated to try to fulfil these asks to the best of my ability. ↩

-

One of my student academic appointments during the research for this dissertation was with the Institute for Digital Arts and Humanities. One of my main duties was to assist in consults with scholars interested in pursuing a project in the digital humanities. One of the main themes we saw with many of our consultees, was a misunderstanding of scope for digital projects, but also a need for further refinement of research questions. ↩

-

Radin, Joanna. Life on Ice: A History of New Uses for Cold Blood. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2017;

[!!!ADDKimTallBear?] ↩

-

This claim is, perhaps, wrong. Scholars like Guiliana Bruno has interrogated the histories of media art and video art in ways that maintain and reinforce the materiality of the light—the film of the projected image.

Guiliana Bruno. [!!! Cite this] ↩

-

Chris Marker. Sans Soleil, 1984. ↩

-

Rawling piece. ↩

-

Christen, Kimberly. “Does Information Really Want to Be Free?: Indigenous Knowledge Systems and the Question of Openness.” International Journal of Communication 6 (2012): 2870–93; Christen, Kimberly. “Gone Digital: Aboriginal Remix and the Cultural Commons.” International Journal of Cultural Property 12 (2005): 315–45. ↩