Chapter 1

Section 1.0

Section 1.1

Section 1.2

Section 1.3

Please use the buttons above to toggle the opacity of images and text.

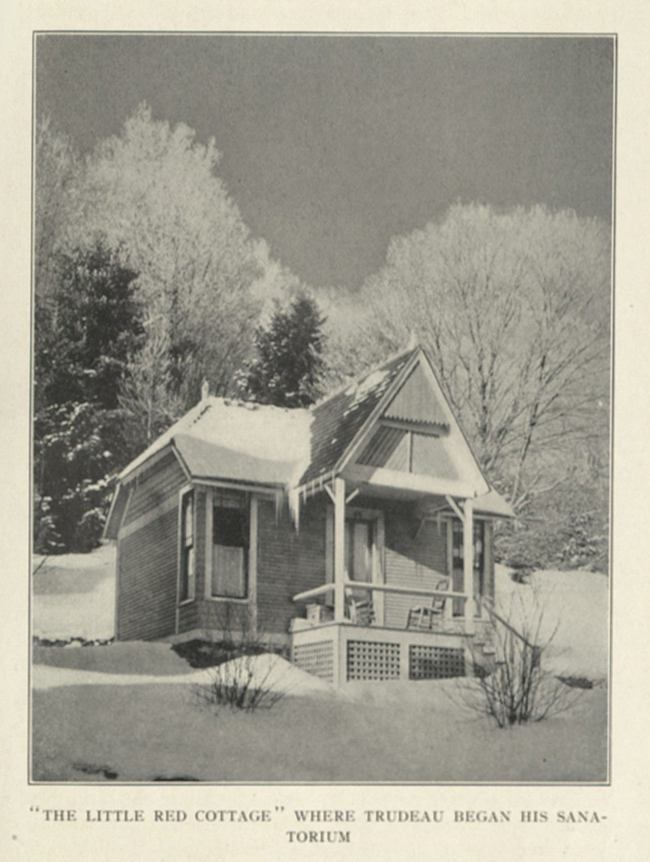

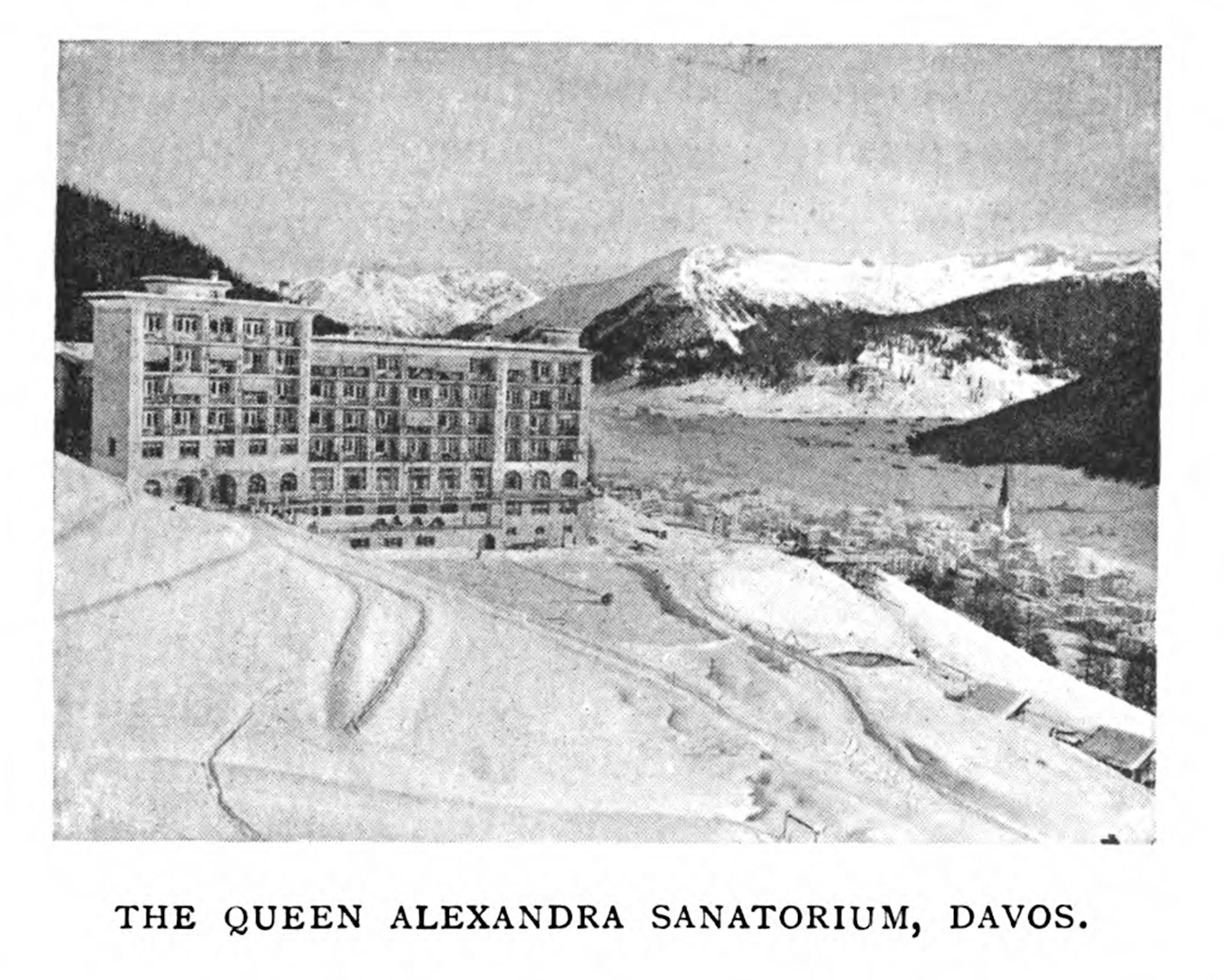

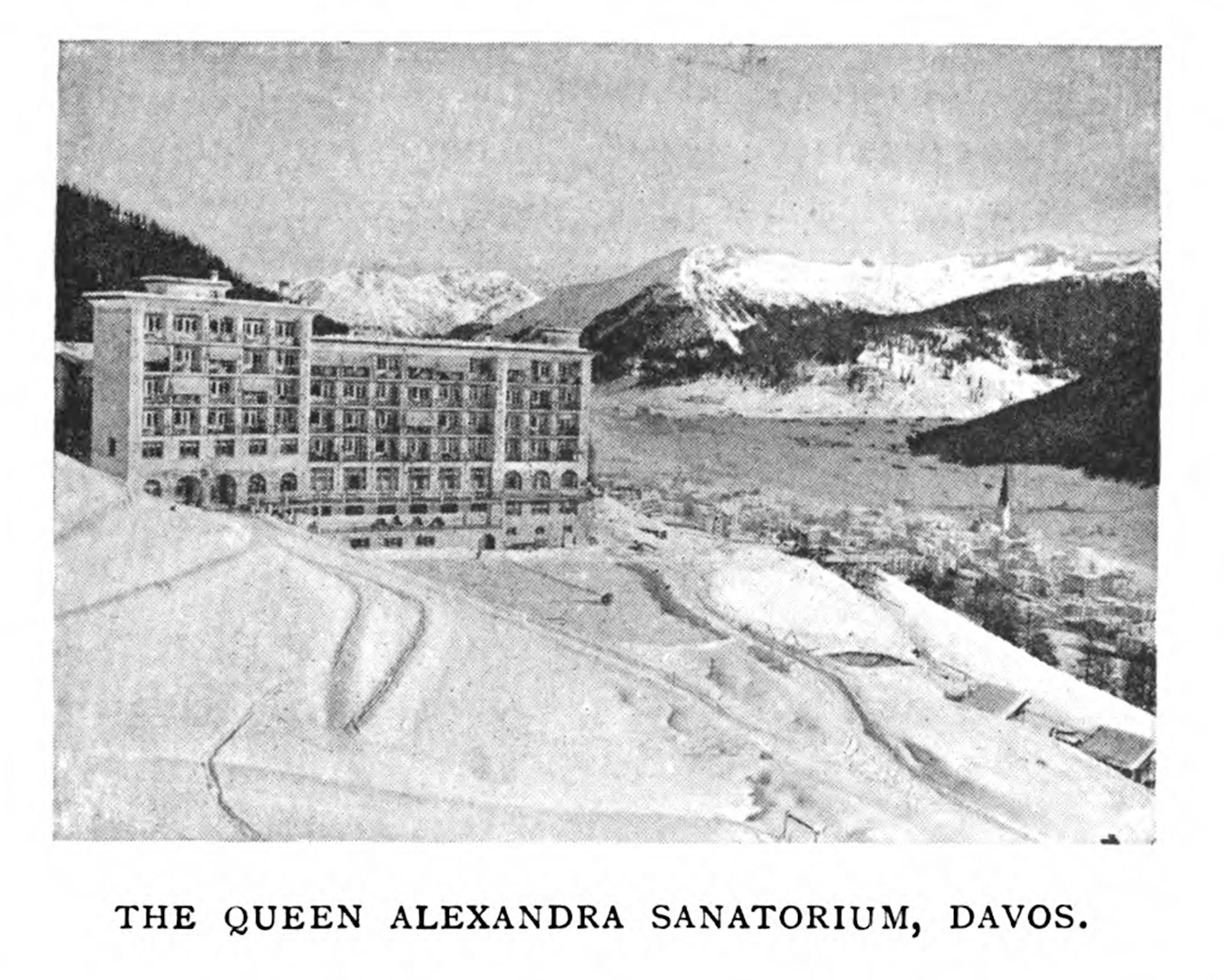

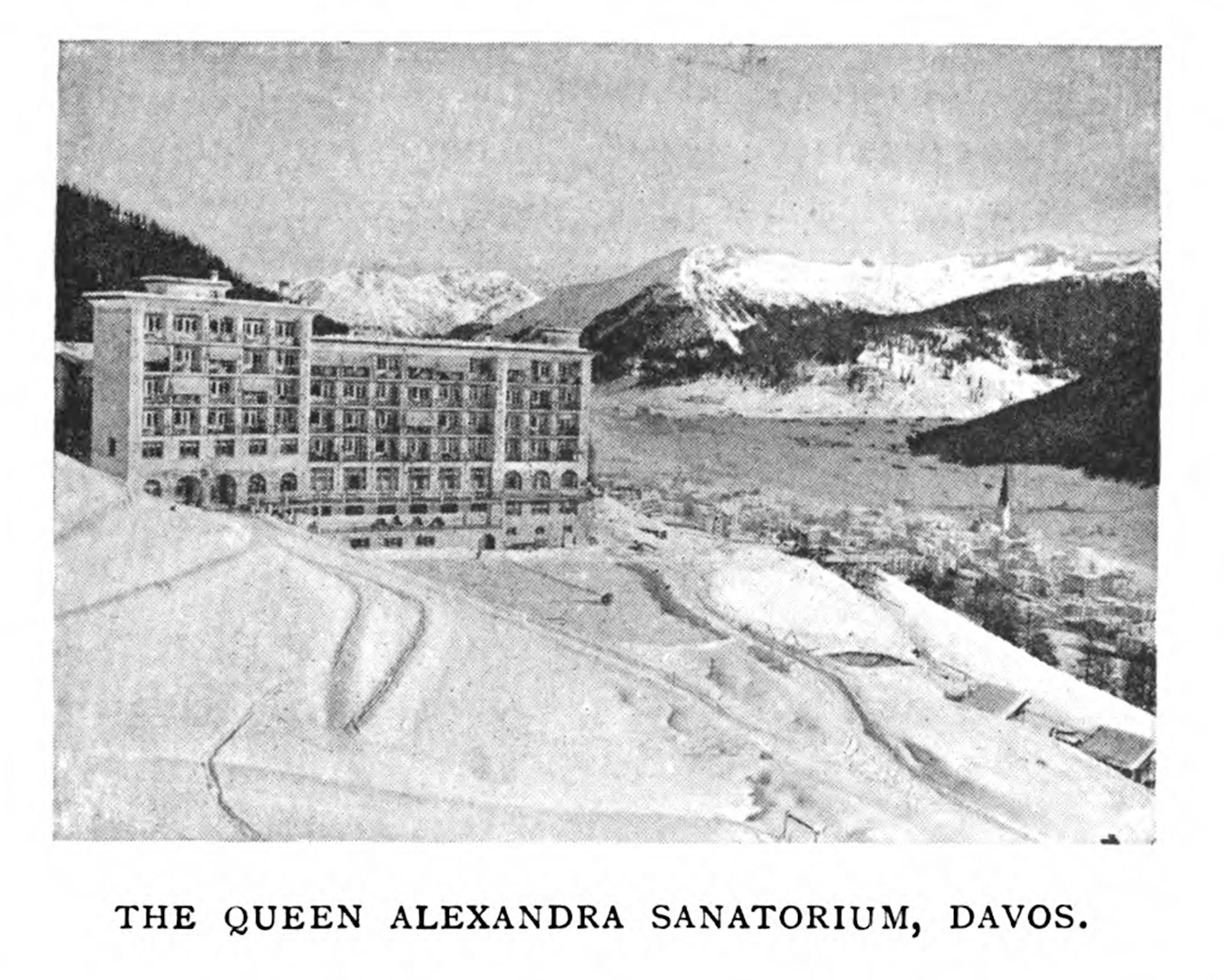

1.1.1 Tuberculous Cultures

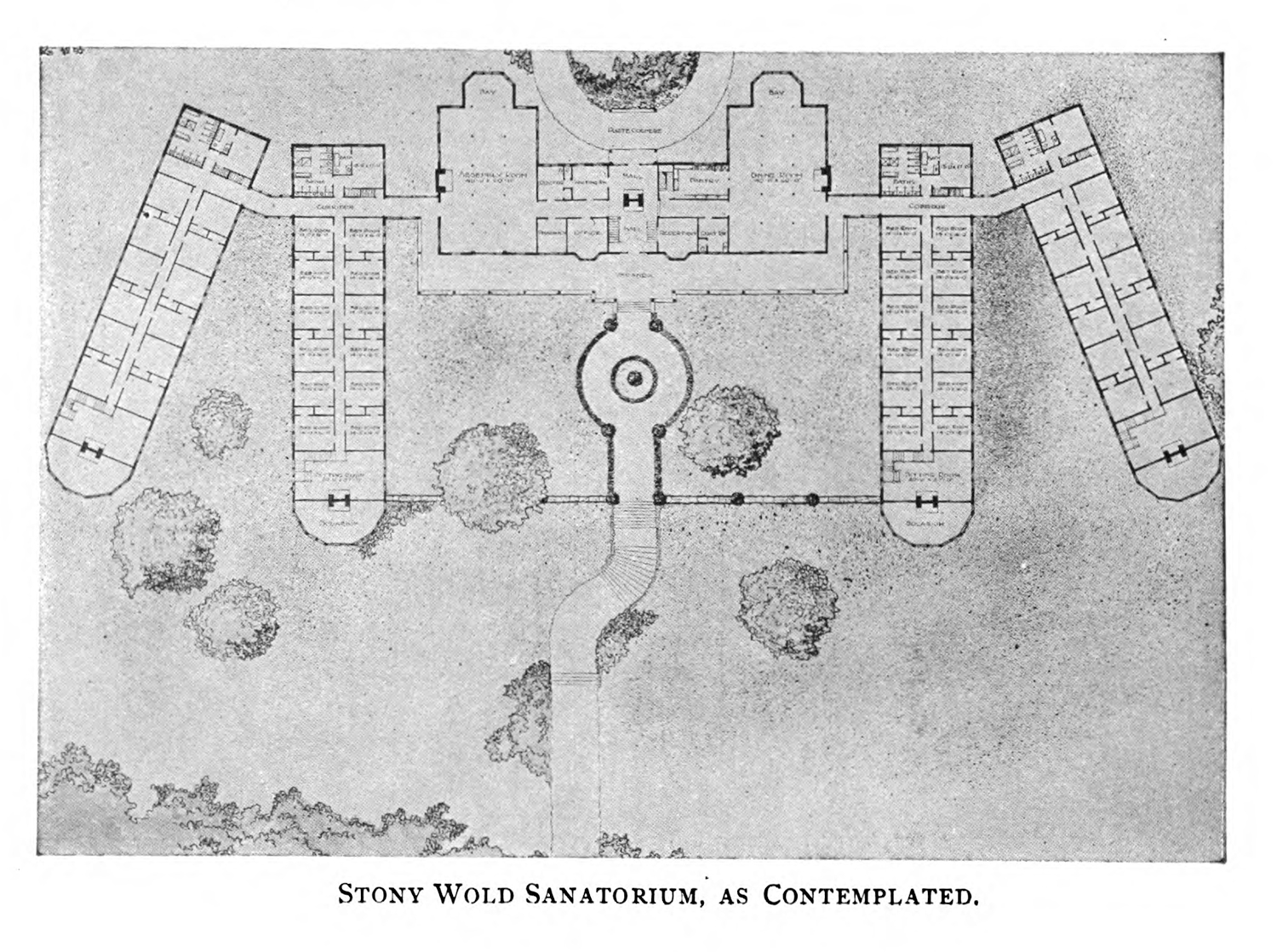

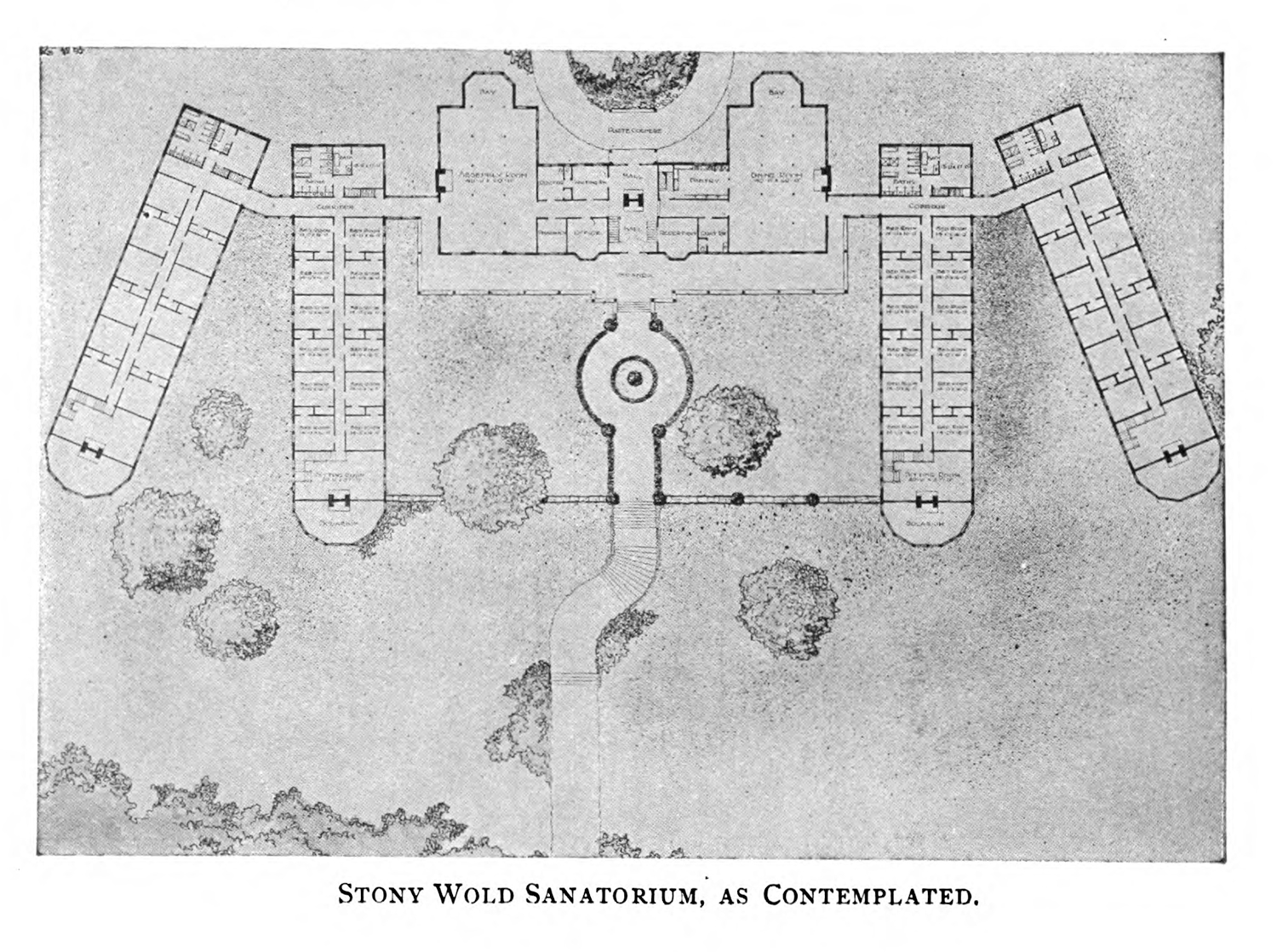

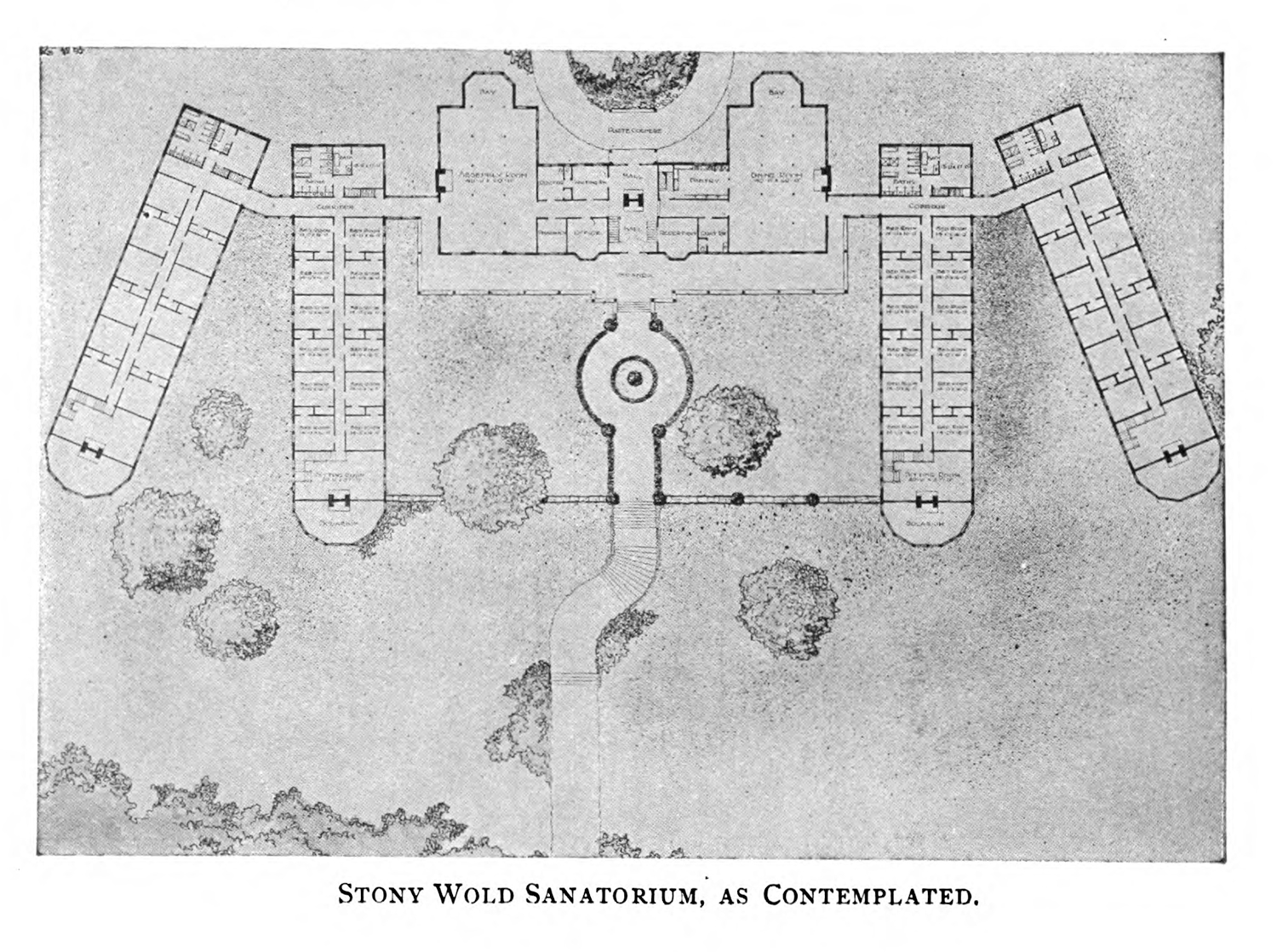

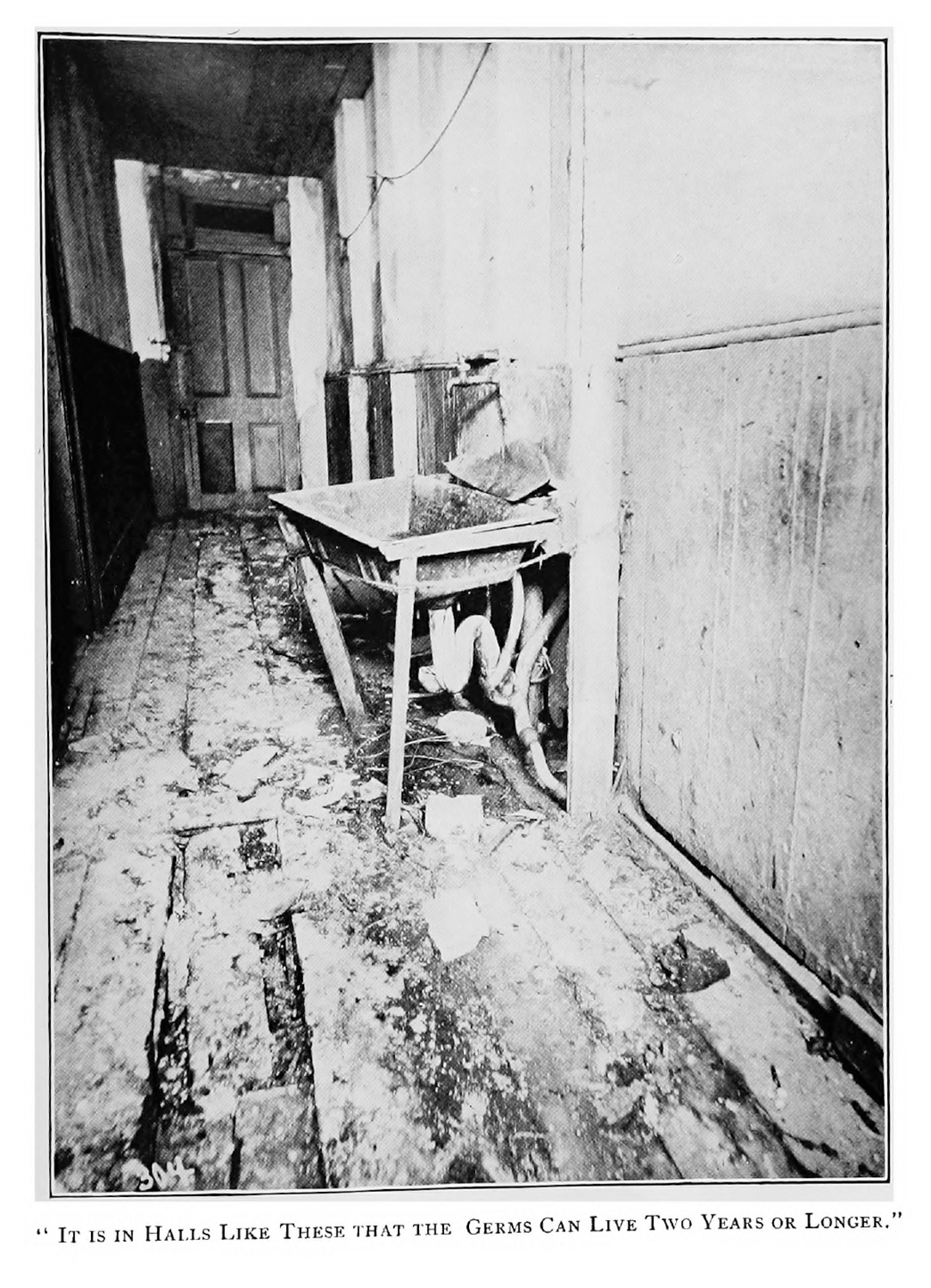

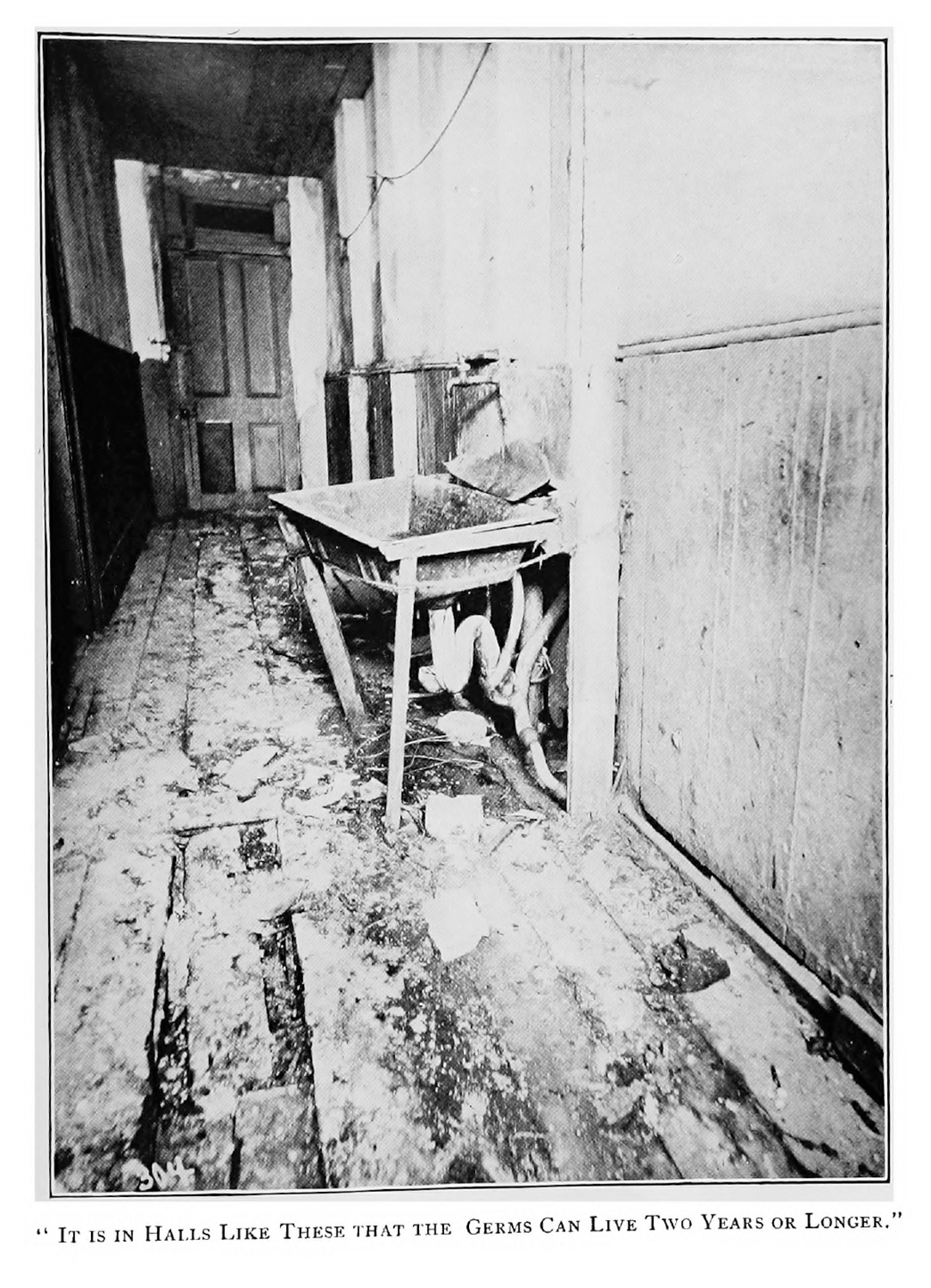

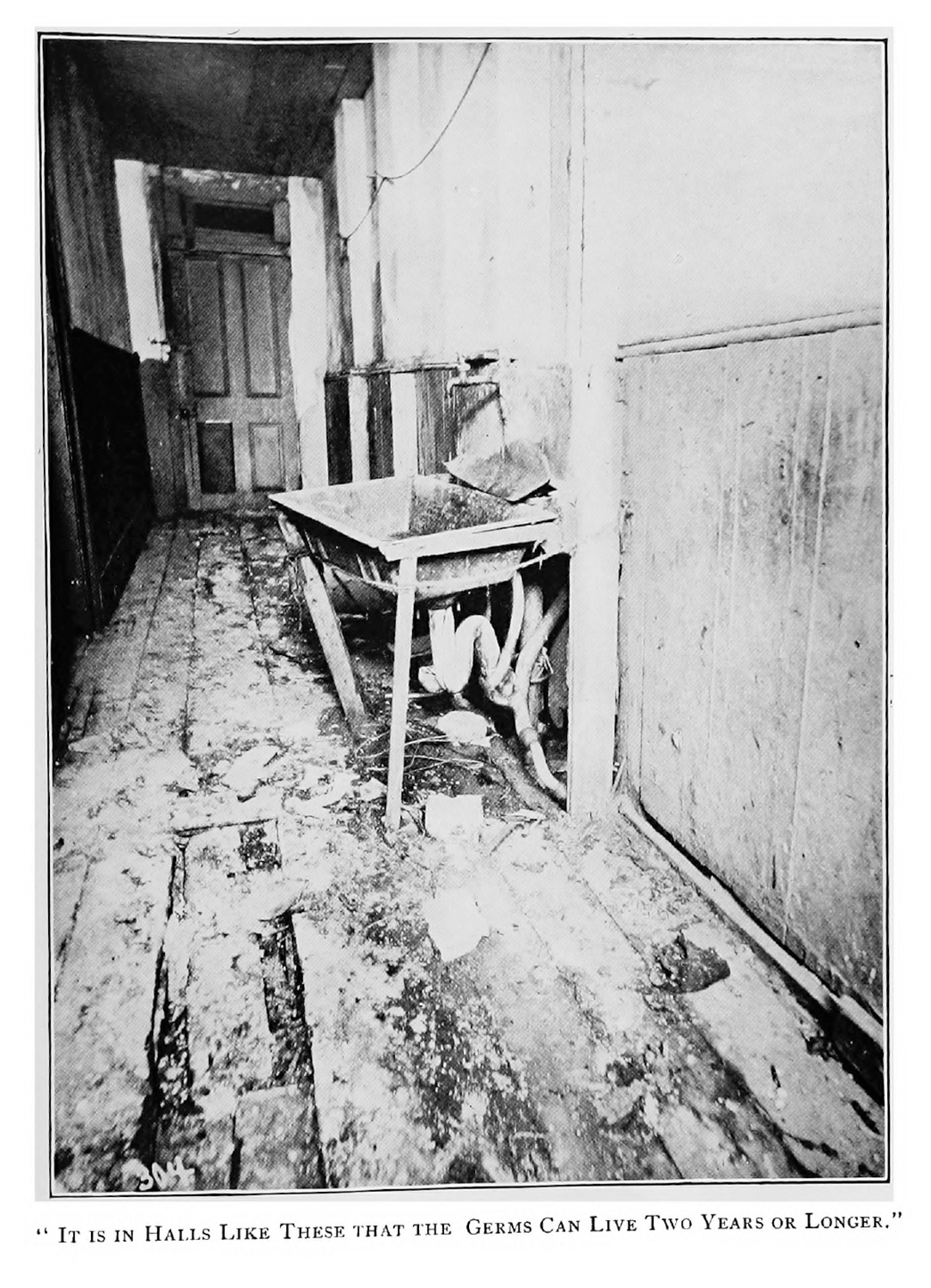

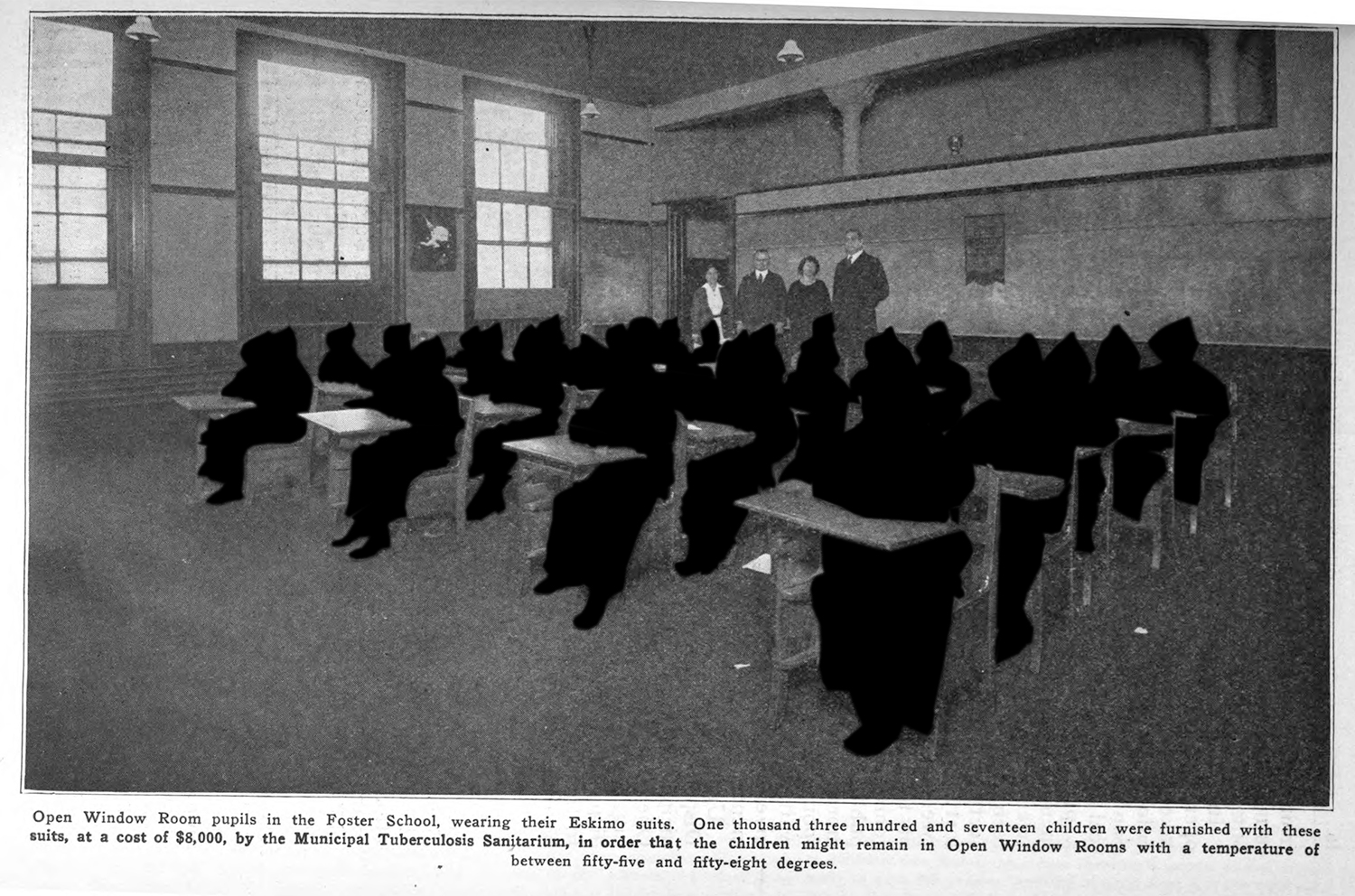

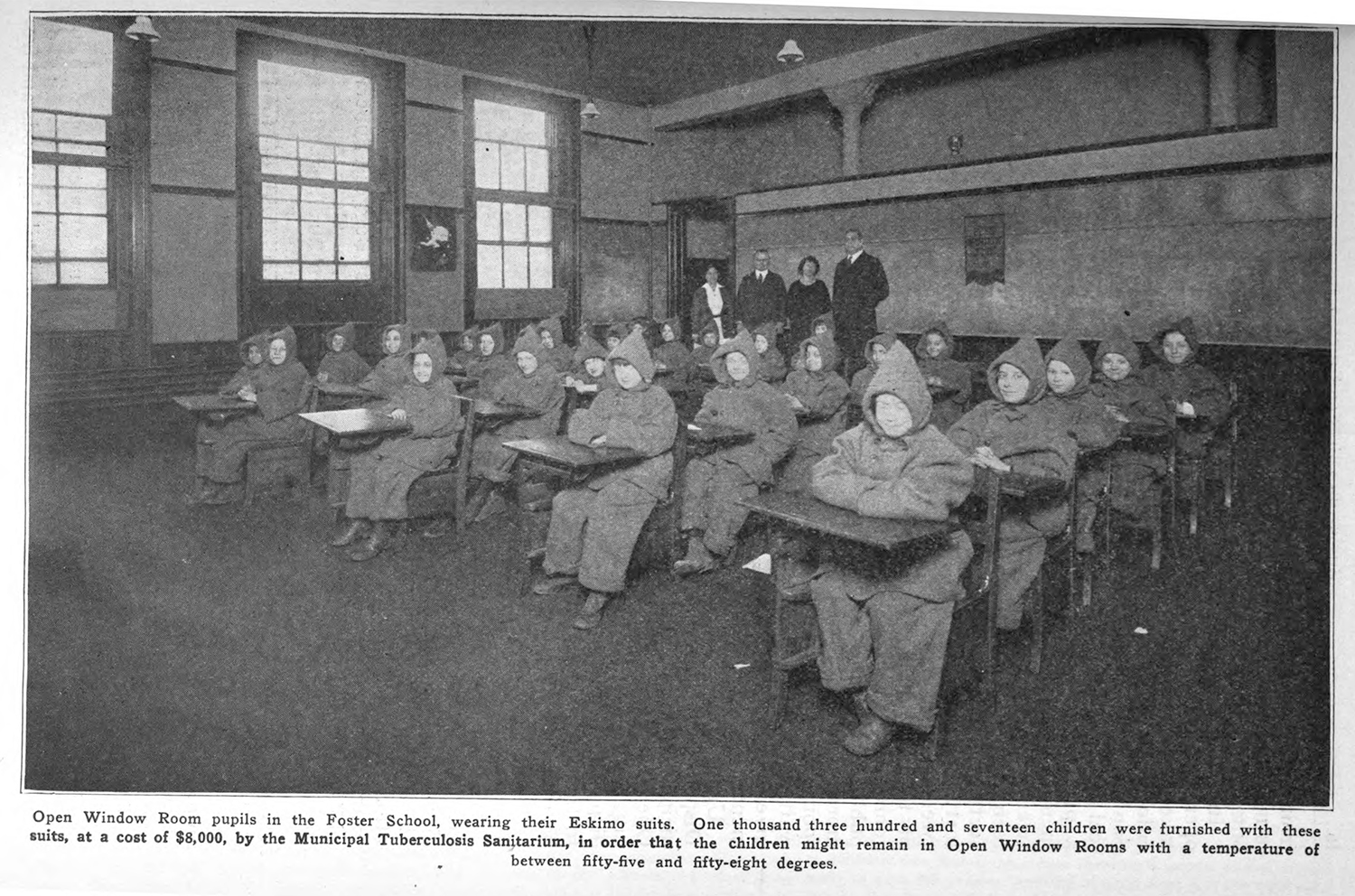

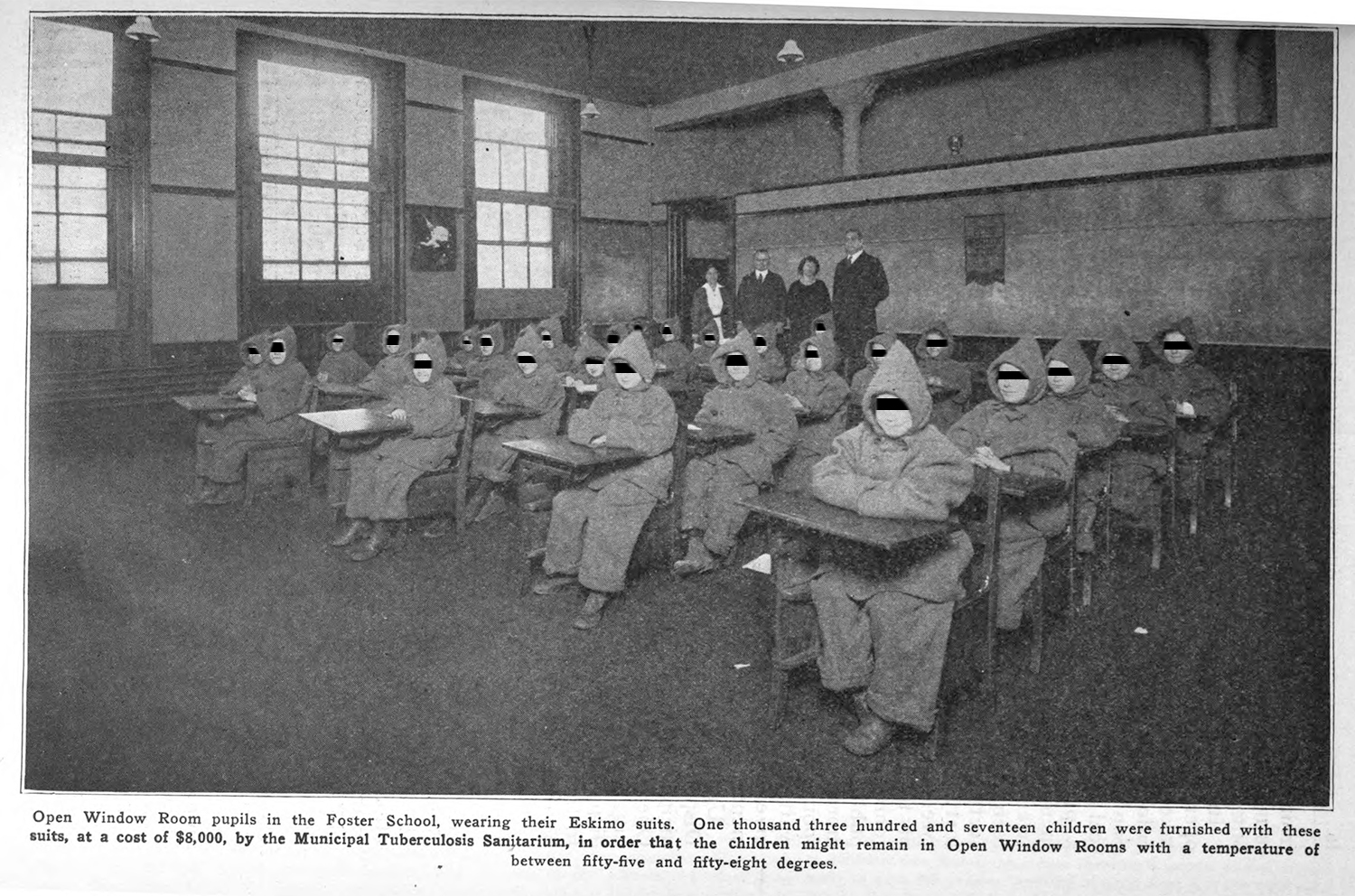

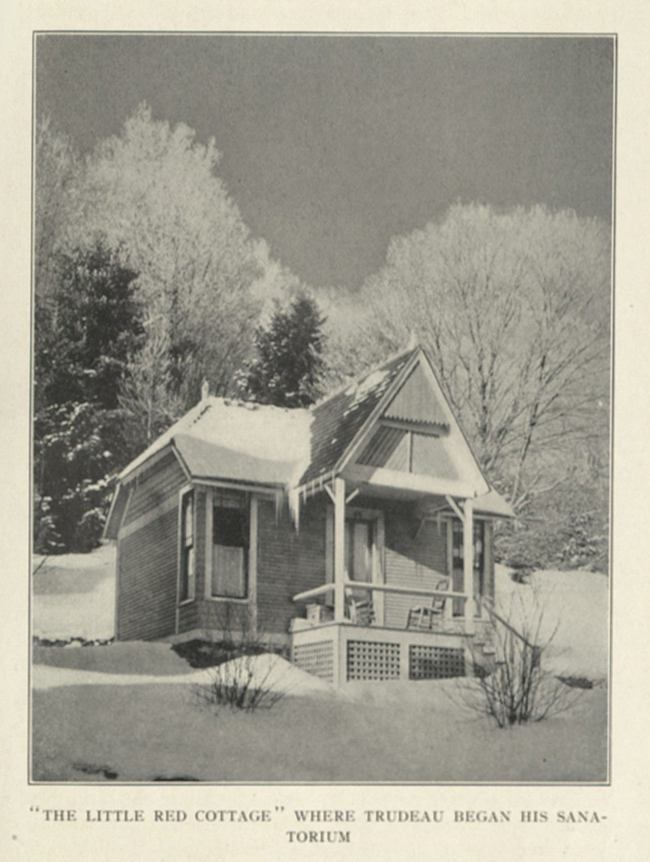

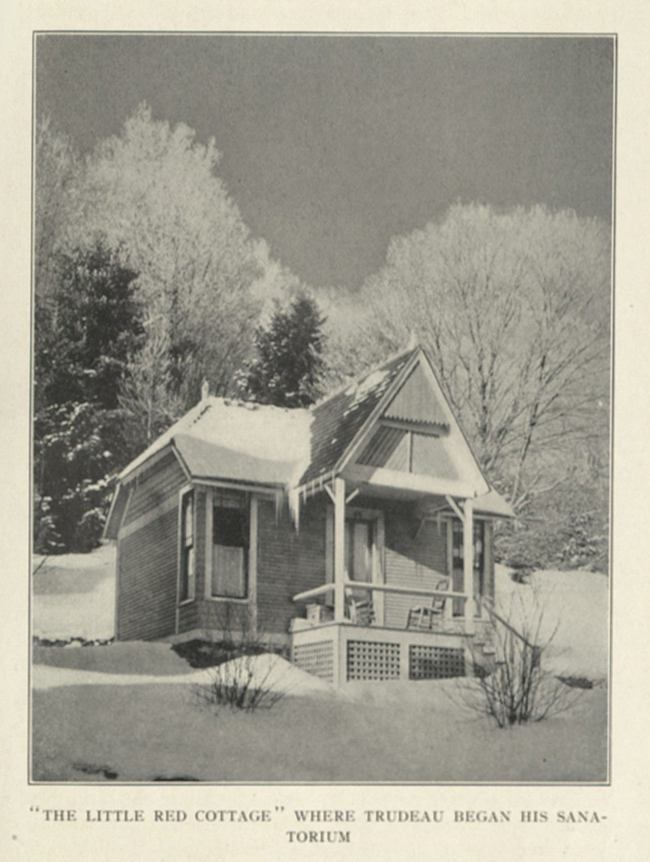

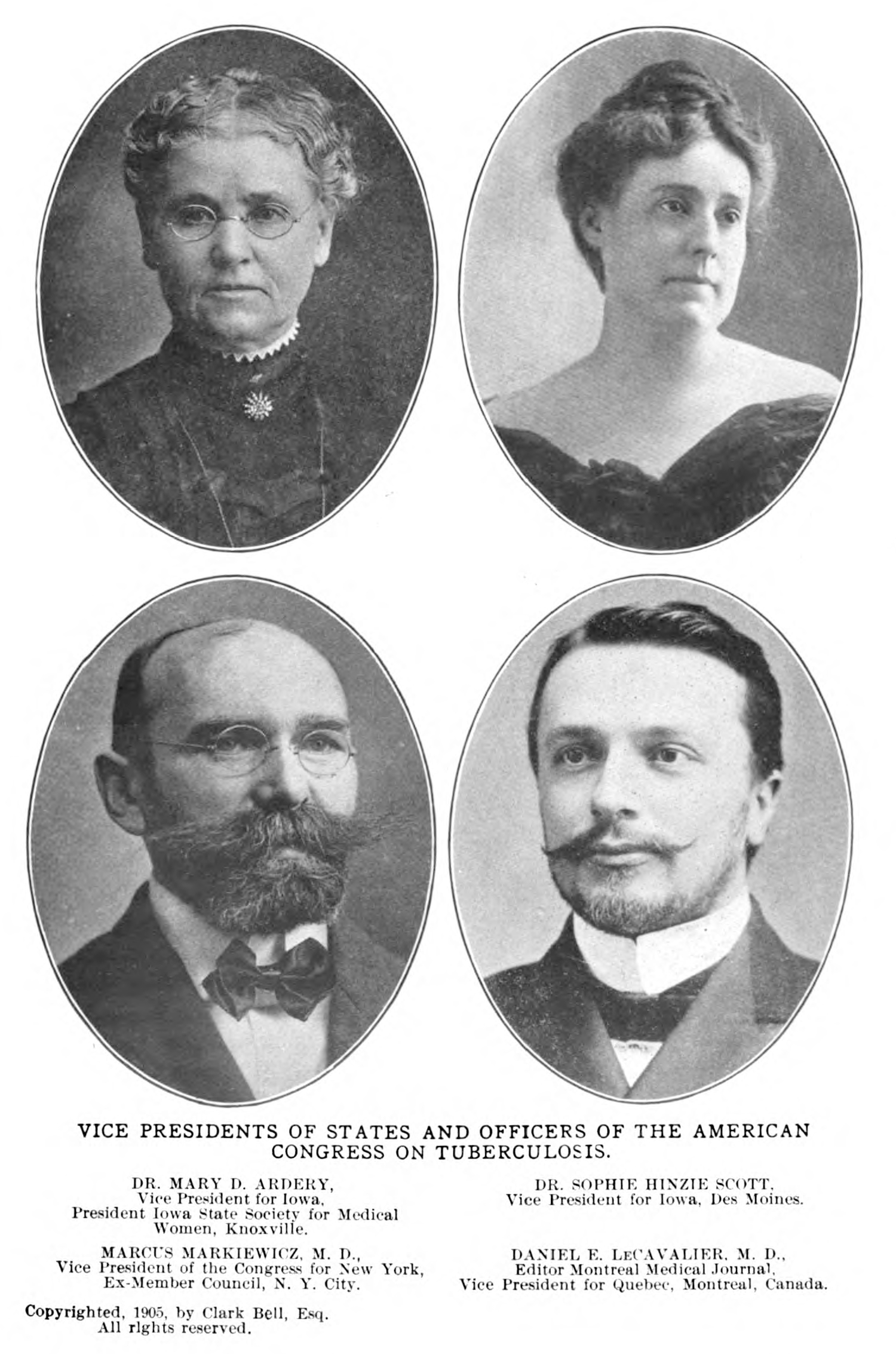

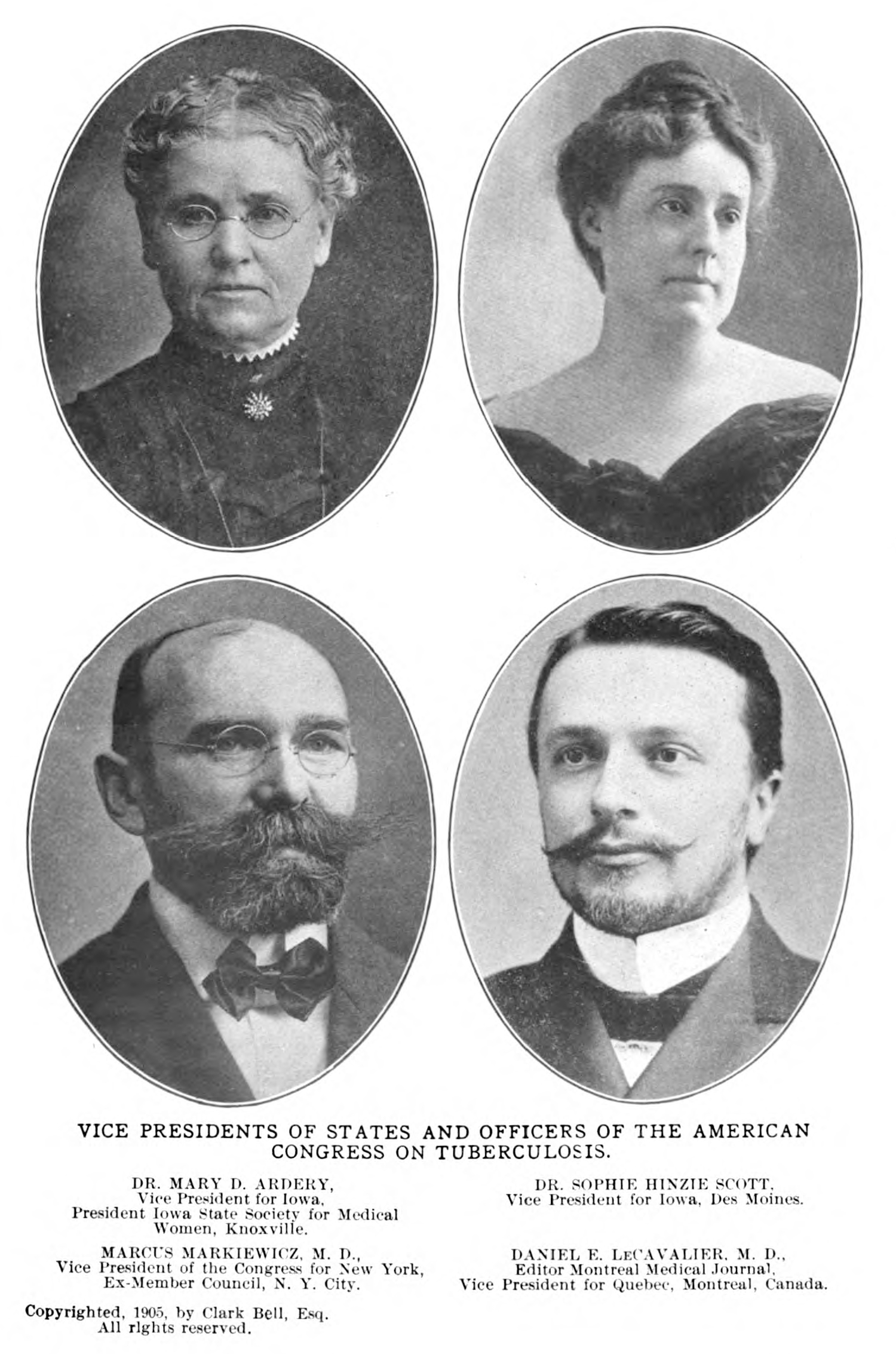

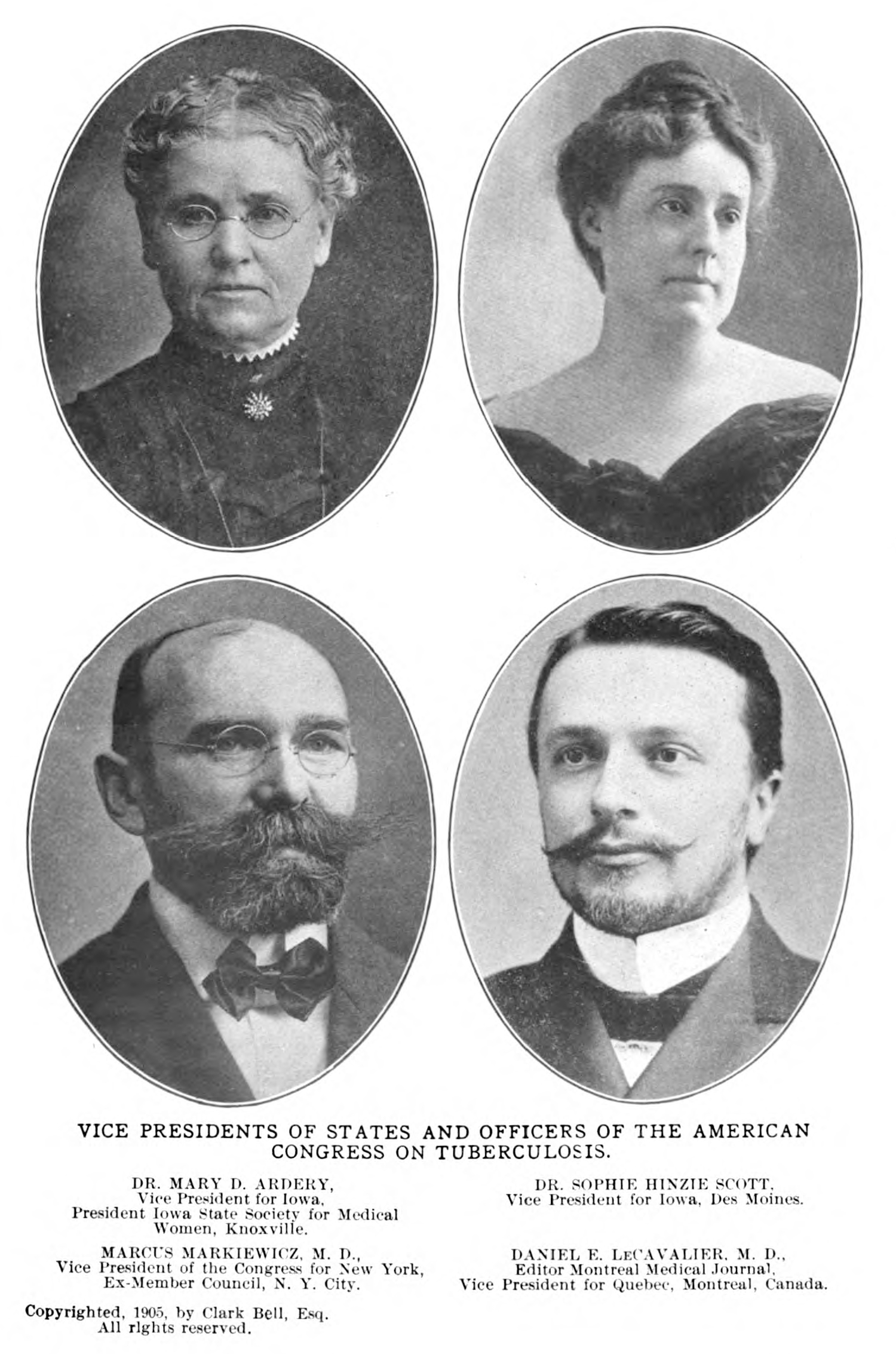

In developing the corpus and image dataset for this dissertation (0.x.x; x.1.x), I ran across a bulk of images that surprised me. Out of the thousands of images which my coders and I processed a huge percentage of them [around 50% at present count] had little to do with the kinds of examination which rely on an extractivist construction of the specimen (0.x.x). What does a child selling postage seals (fig. 1), an architectural floor-plan for a sanatorium (fig. 2), an image of a filthy room (fig. 3), images of children studying in heavy coats (fig. 4), and a photograph of a cottage (fig. 5) have to do with the scientific understandings of the disease? What about a photograph of idyllic mountain resort (fig. 6), a portrait of a doctor taken for a conference (fig. 7), or a graphic of a flapper dancing with death (fig. 8) have to do with the ways doctors saw and treated their patients?

Figure 1. A photo of a girl selling Christmas seals. These stamps were used to fundraise for the National Association for the Study and Prevention of Tuberculosis, and are still sold as part of the American Lung Association’s yearly fundraising efforts. Knopf, S. Adolphus. Some Additional Notes on the Prevention of Relapses in Cases of Arrested Tuberculosis. 1921. Image courtesy of the New York Academy of Medicine.

Figure 2. An example of an architectural drawing as they appear in the tuberculosis corpus (X.1.0). Brandt, Lilian. A Directory of Institutions and Societies Dealing with Tuberculosis in the United States and Canada. New York, 1904.

Figure 3. An example of the way dirty spaces are shown in hygienic discourses around tuberculosis. The Charity Organization Society of the City of New York. A Handbook on the Prevention of Tuberculosis. New York: The Charity Organization Society of New York City, 1903.

Figure 4. City of Chicago Municipal Tuberculosis Sanatorium Monthly Bulletin. 1917-1924.

Figure. 5. “The Little Red Cottage”, the first building that Edward Livingston Trudeau treated patients within at the Adirondack Cottage Sanitorium. Knopf, S. Adolphus. Some Additional Notes on the Prevention of Relapses in Cases of Arrested Tuberculosis. 1921. Image courtesy of the New York Academy of Medicine.

Figure 6.

Figure 7.

Figure 8. Image courtesy of the New York Academy of Medicine.

Early on in my research, I had assumed that scientific medicine was defined by the clinical gaze—a singular way of seeing the sick patient in a way that emphasizes contrasts between a healthy ‘normal’ anatomy and unhealthy ‘abnormal’ pathology, resulting in an objectification of the sick subject (2.x;x). Visual culture scholars like Katherine Waldby, Jose van Djick, Erin O’Connor, and Lisa Cartwright have convincingly articulated the ways clinical visuality has been embraced in practice and in the technologies of medical research and diagnosis, and my assumption was that most of the images in the corpus would correspond with the alienating, dehumanizing clinical gaze and its technological mediation in the clinical photograph.Waldby, Catherine. The Visible Human Project: Informatic Bodies and Posthuman Medicine. London & New York: Routledge, 2000; Dijck, José van. The Transparent Body: A Cultural Analysis of Medical Imaging. Seattle & London: University of Washington Press, 2005; O’Connor, Erin. “Camera Medica.” History of Photography 23, no. 3 (1999): 232–44; Cartwright, Lisa. Screening the Body: Tracing Medicine’s Visual Culture. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1995. These images, being non-specimen images,Specifically images not tagged with the specifically epistemic tags like “Anatomical” “Pathological” or references to extraction like “Organ”. were outside the remit of my initial research, but muscled their way in as a prominent practice which deserved attention.

This chapter addresses this surprising observation with a series of questions: what are some of the broader assumptions which encircle the treatment of tuberculosis? How are these reproduced in visual media? How do they display differing visual practices in the history of medicine? And in what ways do these images reinforce the classist, racist, and ableist ideologies in the health sciences?

I ask these questions first because of the implicit connections between tuberculosis research and the other cultural actors producing images. Some of the visual material is closely related to scientific research, as with the cases of material in public-facing magazines published by sanataria with research capabilities (The Sanatorium and the first few volumes of The Journal of Outdoor Life). Other materials were linked to public health and volunteer organizations like the Anti-Tuberculosis Health League or the Charity Organization Society of the City of New York, and others are public-facing books that are meant to help tuberculous patients find sanataria, understand how to treat their loved ones, or provide help about hygiene. Beyond this, even more images come from self published or regionally published materials that may or may not have any association with the broader scientific discourses around the disease. This broad range of publications speaks also to a wide array of writers and readers, and where a visual practice like the clinical gaze may be trained in doctors, many of the publishers and audiences may bring their own world views, ideologies, and preconceptions into the discourse.

My interest for this chapter is to try to wrangle the sometimes disparate threads which knot around tuberculosis in this period. This chapter makes two arguments: first, in response to the excellent scholarship by my peers who analyze medicine and its cultures, I stress a need to look at medical visual culture in the plural. Medicine has not, and never has had, a singular visual culture defined by the clinical gaze. By opening this discourse to competing, overlapping, contested visual practices, I encourage future scholars to explore the idiosyncratic practices by medical doctors, patients, and others working in health. Moreover, where I am talking about tuberculosis—with its Romantic metaphors,Sontag, Susan. Illness as Metaphor and AIDS and Its Metaphors. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1990. its use to forward xenophobic policies of exclusion (1.3.5),Abel, Emily K. Tuberculosis & the Politics of Exclusion: A History of Public Health & Migration to Los Angeles. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2007. and its embrace of idyllic health resorts (1.2.0)—the cultural landscape around other diseases like the AIDS epidemic, cancer research, the 1918 influenza epidemic, or Covid-19 is quite different than the one I describe in this chapter. Future scholarship will help nuance, rebuke, and clarify the claims I make this chapter.A good example of the broad discourses around health can be seen in the double issue of Camera Obscura on medicine and film edited by Paula A. Treichler and Lisa Cartwright. See: Camera Obscura 10(1-2). 1992.

Second, by engaging with the broader cultures around tuberculosis, I hope to onboard readers to some main themes which will become more prominent in the next two chapters. I am going to follow three three mini-case studies—on hygiene, the sanatorium, and the medical practitioner at work—to define some ideological through-lines which will reappear in the next two chapters (2.0.0; 3.0.0). In doing this, my hope is to articulate in clear detail the eugenicist and capitalistic ideas which were reified in the process of fighting the disease. Concepts of class, ability, cleanliness, and health appear in relation to the cultural conception of tuberculosis, as well as the popular and scientific understandings regarding treatment. As Linda Bryder has argued, tuberculosis doctors in the early twentieth century “showed themselves to be very much a product of the middle-class society from which they came, with its fixed assumptions about the poor”,Bryder, Linda. Below the Magic Mountain: A Social History of Tuberculosis in Twentieth-Century Britain. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1988. and this chapter extends this claim to think about how discourses around the disease (made possible by medical professionals, patients, and the lay public) reinforced these structures.