Chapter 1

Section 1.0

Section 1.1

Section 1.2

Section 1.3

This chapter and the next are interested in the socially constructed ways by which cultures see. The discourses around sight have been discussed in the interdisciplinary field known as visual culture, and the visual turn has been successfully leveraged in film studies and art history to tie disparate ideologies into representative objects. Visual culture sees the processes of looking, the “visual event”, as an act which is the result of a co-constituative process of ideology, history, place, and temporality. As Nicholas Mirzoeff defines this process, it is “an interaction of the visual sign, the technology that enables and sustains that sign, and the viewer.”1 So the meaning which is generated from a visual form is not an A to B transmission of idea from object to subject, but instead the result of an array of contestations, from the ideological training of a student to see in an art seminar, to the technologies which afford and demand particular modes of viewing. As Miertzoeff argues, “seeing is not believing but interpreting.”2

Ways of seeing have been tied to ways of knowing, and they help make sense of the various ideologies which are taken for granted in a given culture. The modern viewing subject was constructed by and through scientific experimentation. As Jonathan Crary argues, “[v]ision and its effects are always inseparable from the possibilities of an observing subject who is both the historical product and the site of certain practices, techniques, institutions, and procedures of subjectification.”3 My interest in this chapter, and my call for future scholars of medicine , is to think of a plurality of vision: there are many kinds of different visualities which are leveraged by medical researchers, medical professionals, and anti-tuberculosis volunteers which overlap into differing practices and meanings. This is because there were multiple audiences, multiple contexts, multiple histories, and multiple kinds of science,4 which were interacting in a disparately connected and contested discourse.

This epistemic and practical disparity is the result of some historical problems regarding research into tuberculosis and the culture around it: First, the inability to develop a cure as effective as the antibiotic and chemotherapeutic interventions of the mid-century, led to some disagreement in how to treat the disease.5 Second, in America it would take a number of decades before Koch’s bacteriological etiology would be completely believed. The insistence of heredity, on biological or personal failings which makes a subject more susceptible, and the perniciously classed and raced ideologies which those ideas supported, meant doctors spent decades squabbling over what might be the actual cause.6 Finally, while there were university doctors researching tuberculosis, as well as the beginnings of charity organizations (some funded by communities and other funded by monopolists of the gilded age) interested in researching the disease, the funds for research into the disease were sparse. This is best evidenced by the lack of grant funding by the nation’s largest anti-tuberculosis organization, The National Association for the Study and Prevention of Tuberculosis (NASPT). This shifted in 1920, when NASPT (through a fund jointly created with James Alexander Miller, H. Kennon Dunham, and Henry B. Platt) awarded its first $500 research grant to William Snow Miller, a respiratory specialist who published regularly in The American Review of Tuberculosis,7 and whom in the decades following, write a book on the human respiratory system titled The Lung. Before this first grant, the organization had primarily been interested in awareness and not research, and had possibly been sidetracked by the United States’ involvement in the First World War.8

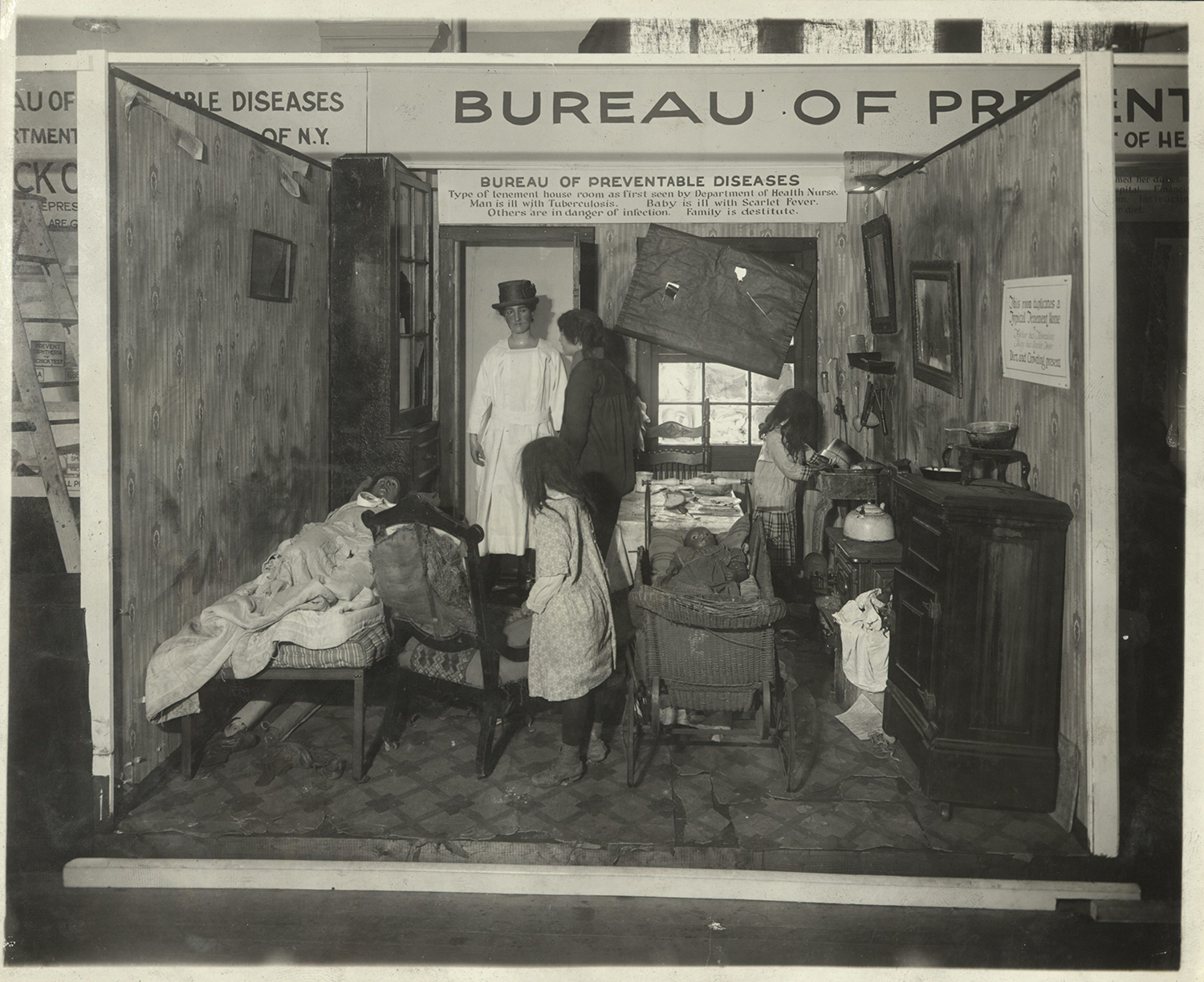

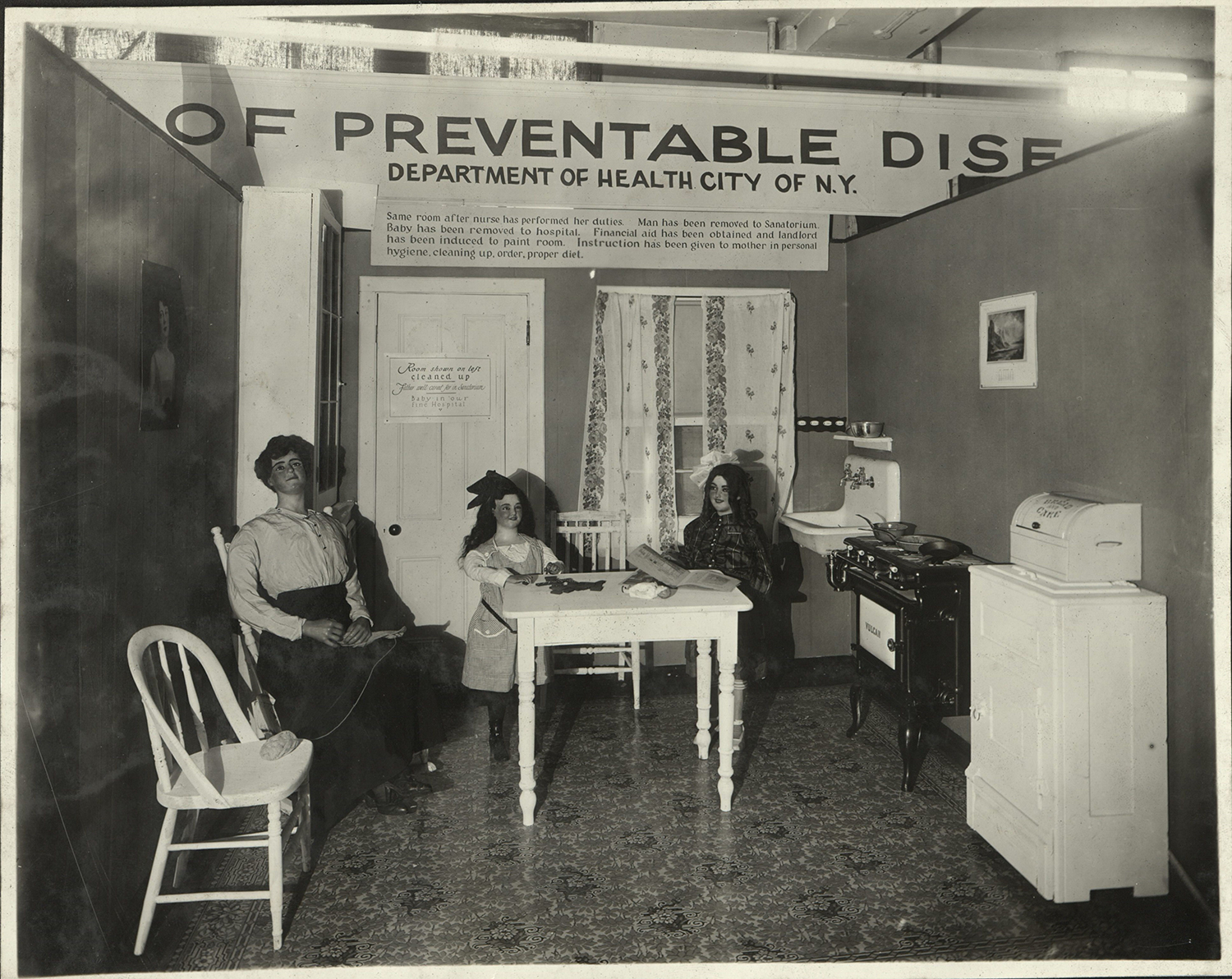

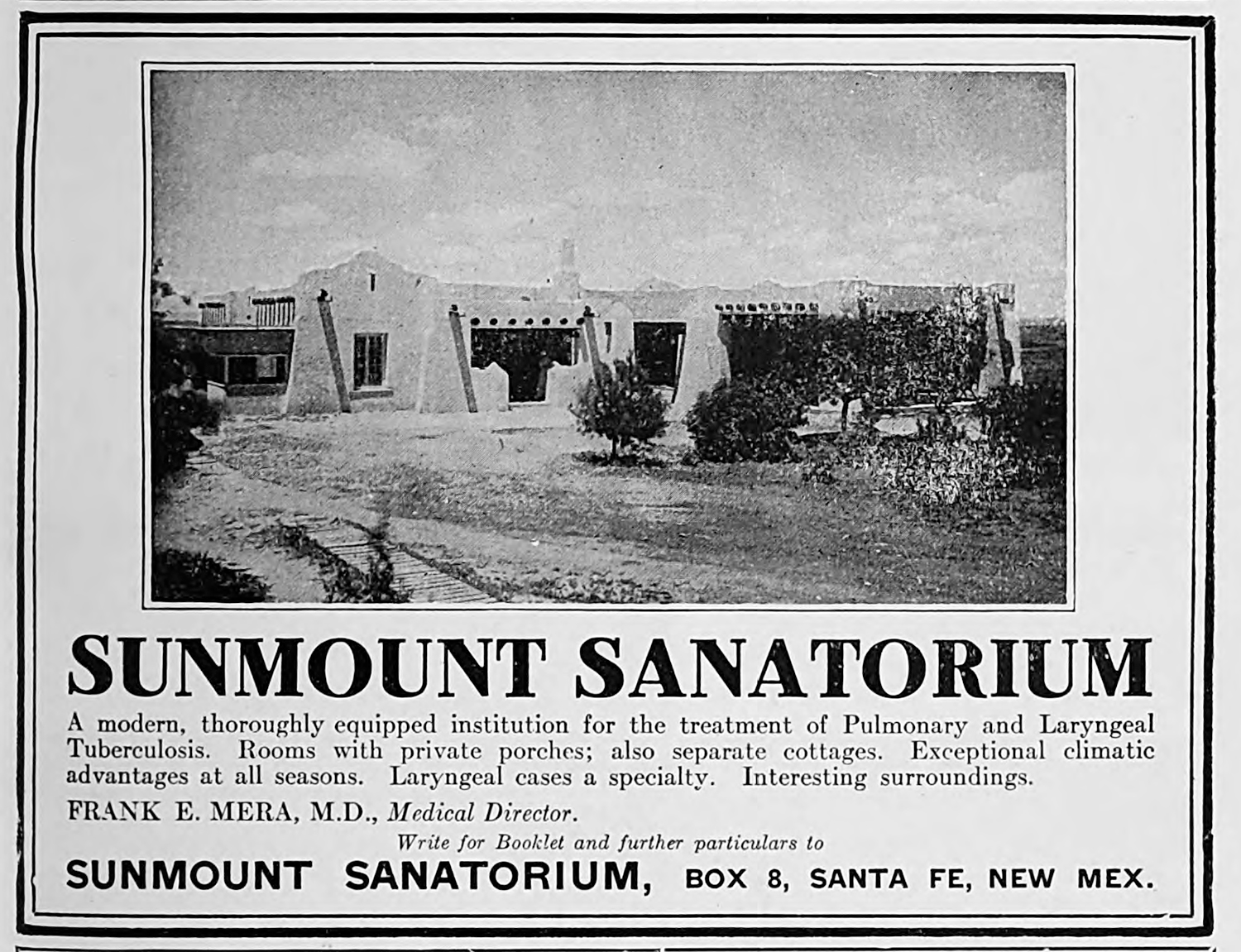

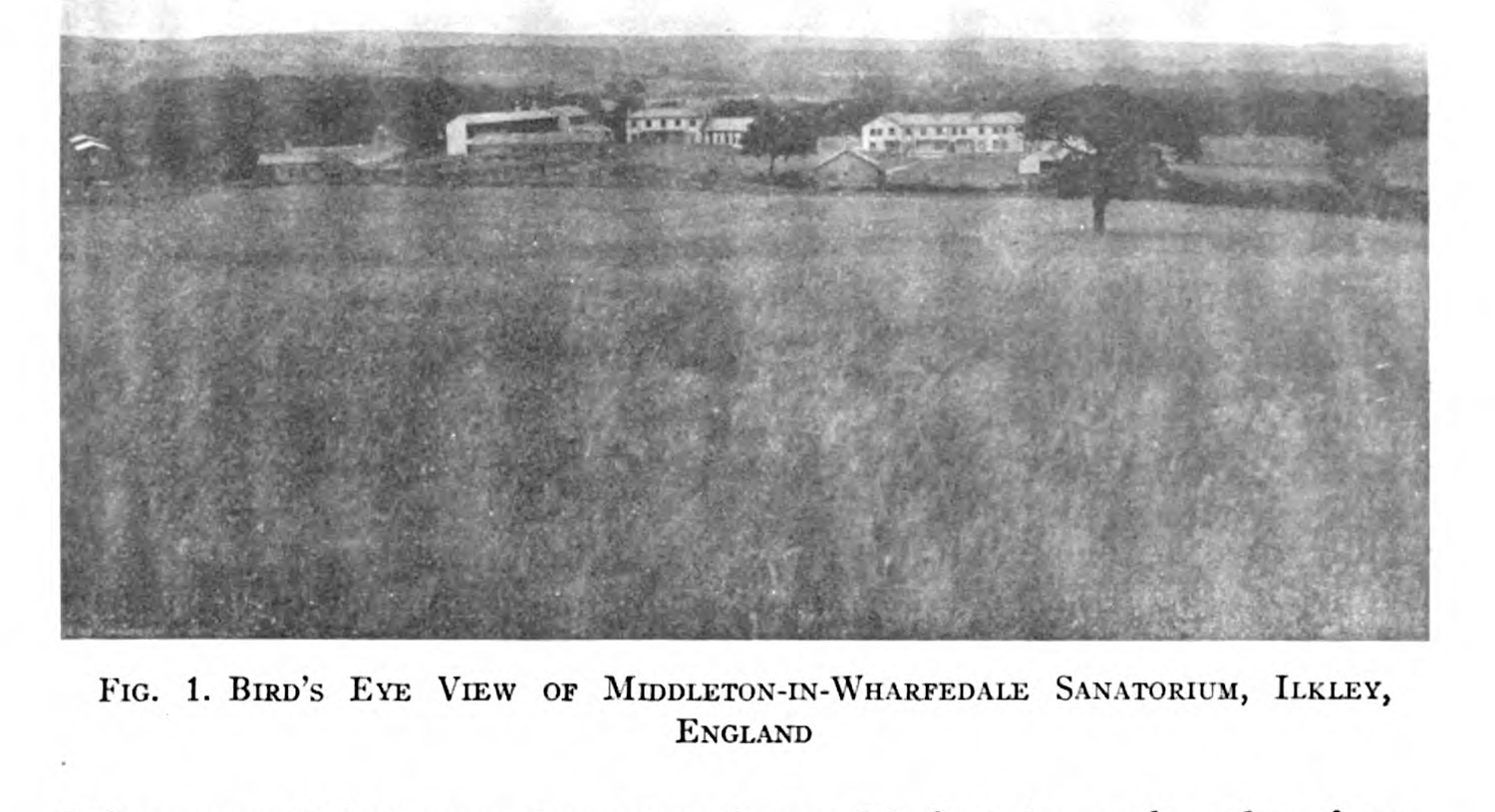

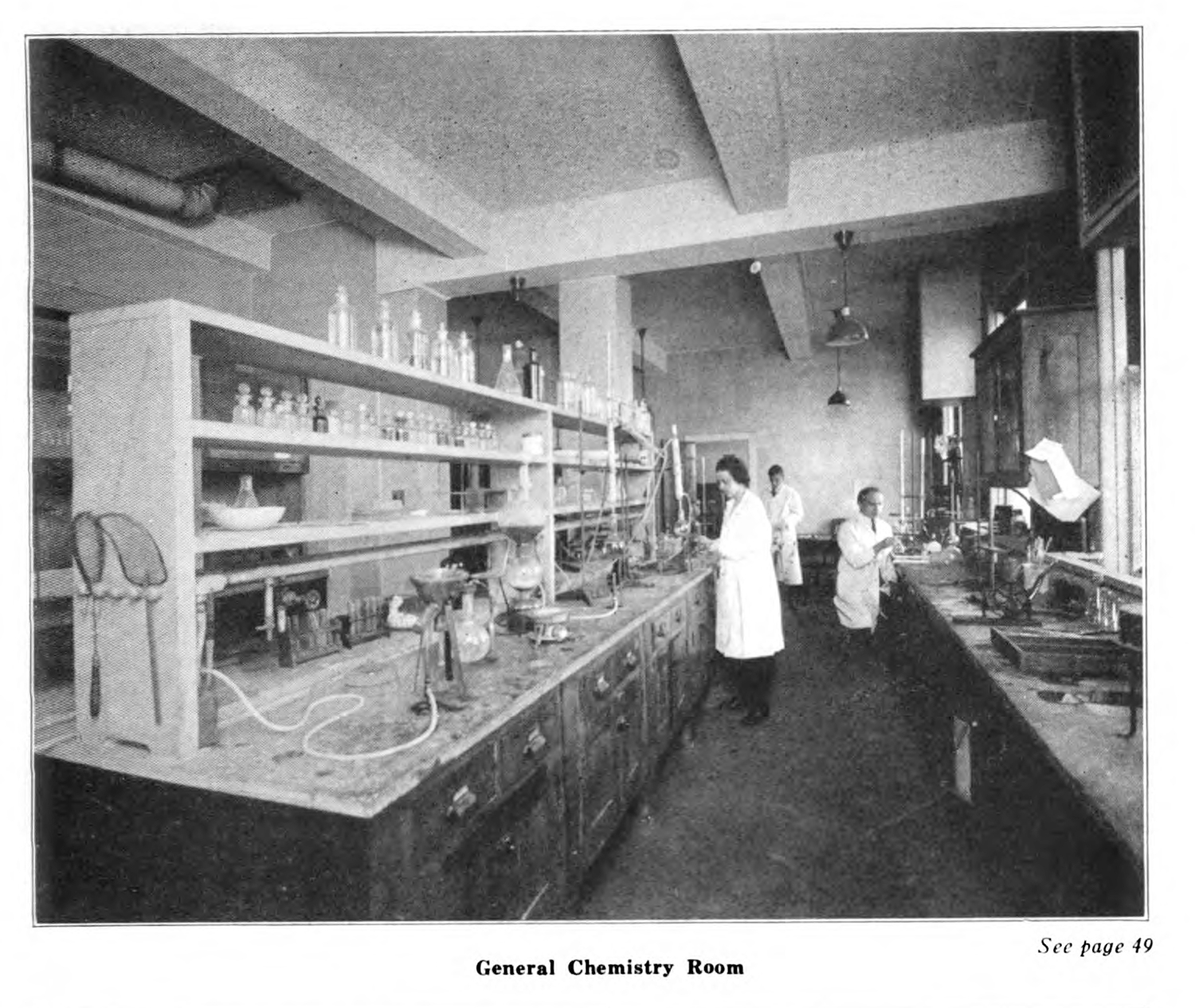

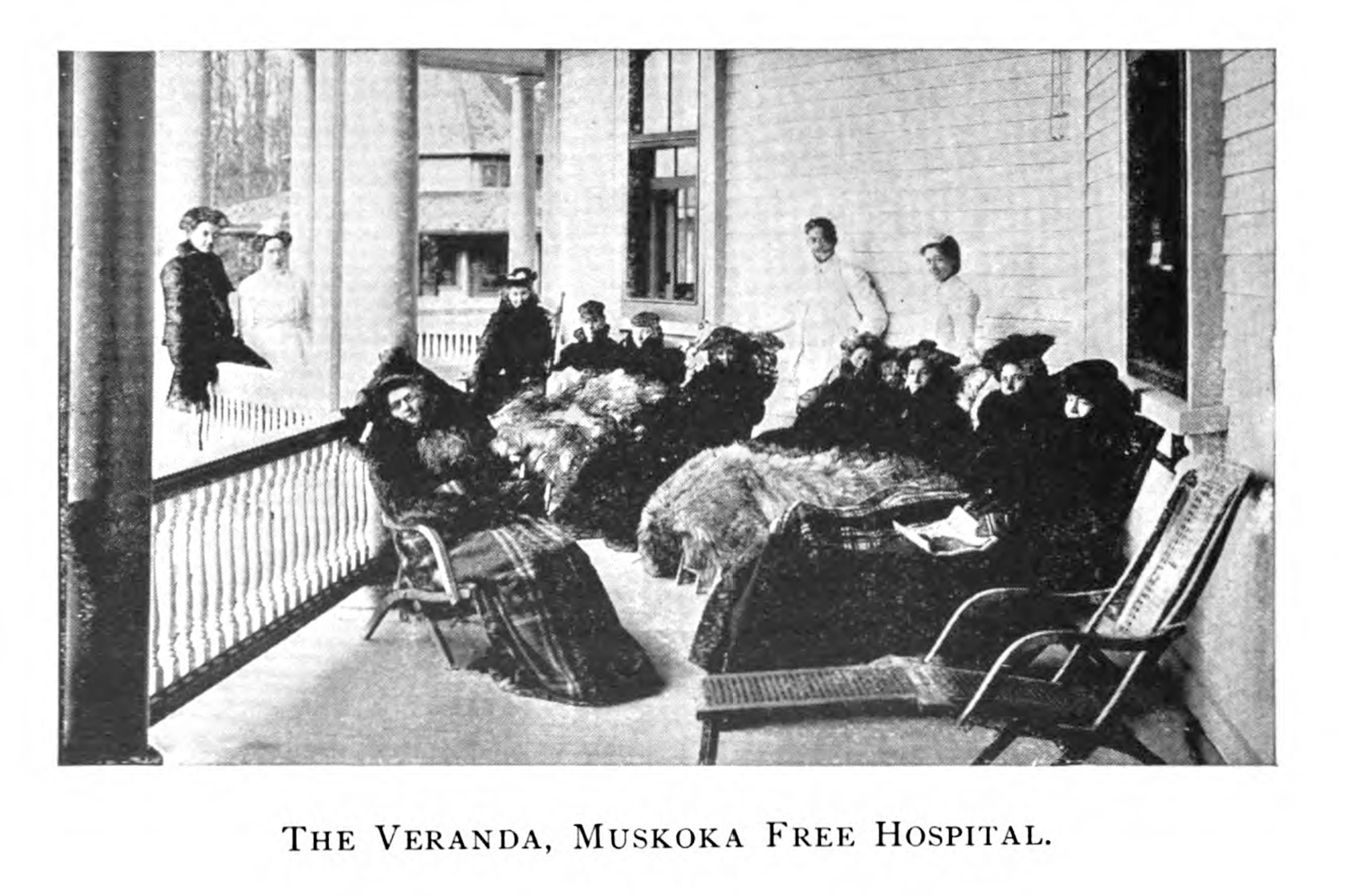

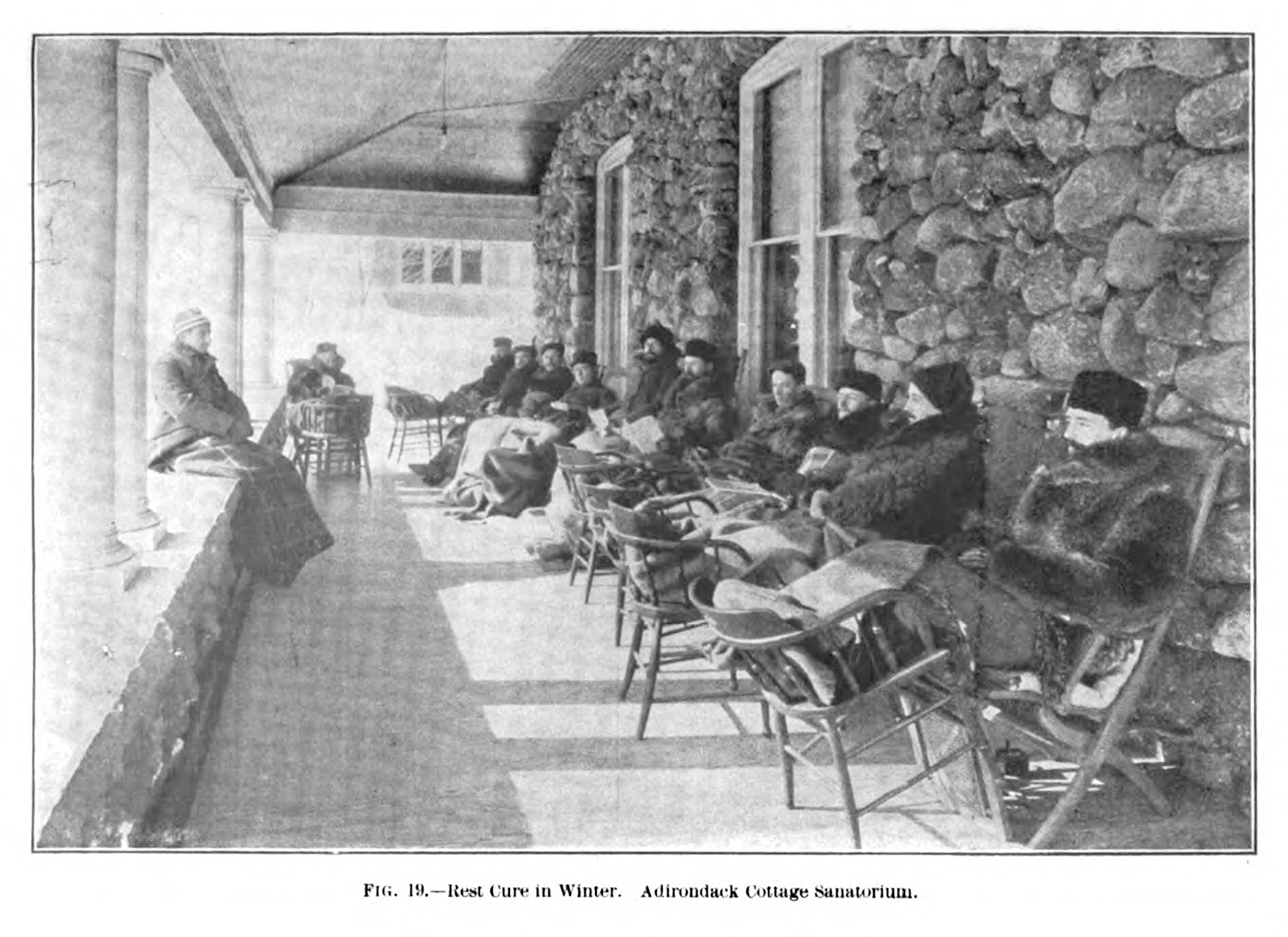

As the corpus is quite broad (X.2.1), many different kinds of actors were included in the materials: the public health campaigns, raising money through Christmas seal campaigns (fig. 1) or displaying health information through exhibits (figs. 2 & 3); the sanatoria which both promoted themselves (fig. 4) and attempted to show their therapeutic bonafides through scientific publications (fig. 5); the doctors who also had to construct their own authority and value, through various kinds of portraiture (figs. 6 - 7); and the patients who are there posed or candid (figs. 8 & 9. These images were produced by a range of different actors (sanatoria, charity organizations, public health offices, individual authors, scientific journals) to a relatively broad audience (other medical professionals, those sick with tuberculosis, those with family who were sick, the public at large).

Figure 1. An example of a Christmas seal. These popular pieces of postage were sold every winter to help fundraise for tuberculosis research. In [!!!Year] they were adopted instead for lung research. The Journal of the Outdoor Life: The Anti-Tuberculosis Magazine 6. (New York: Trudeau Sanatorium, 1909). [!!!Pagenumber]

Figure 2. An exhibit showing the unhealthy living condition of the poor in New York City. The banner above the exhibit reads “Type of tenement house room as first seen by Department of Health Nurse. Man is ill with tuberculosis. Baby is ill with Scarlet Fever. Others are in danger of infection. Family is destitute.” Image courtesy of the New York Academy of Medicine.

Figure 3. An exhibit next to the one pictured above. Hygienic living has improved the lives of the family hear. The banner above the exhibit reads: “Same room after nurse has performed her duties. Man has been removed to Sanatorium. Baby has been removed to hospital. Financial aid has been obtained and landlord has been induced to paint room. Instruction has been given to mother in personal hygiene, cleaning up, order, proper diet.” Image courtesy of The New York Academy of Medicine.

Figure 4. A example of an advertisement for a sanatorium in Santa Fe, New Mexico. The Journal of the Outdoor Life: The Anti-Tuberculosis Magazine 7. (1910). [!!!PageNumber]

Figure 5. This image was used in an article reviewing the public health efforts in the United Kingdom. McDougall. “Notes on the Antituberculosis Campaign in the West Riding of Yorkshire, England,” The American Review of Tuberculosis 5. (1921-1922), 793.

Figure 6. Robert Koch’s portrait is commonplace in many publications, as his influence on the public and professional campaigns against tuberculosis was great. There was [!!!One publication]. Birnbaum, Max. Prof. Koch’s Method to Cure Tuberculosis Popularly Treated. (Milwaukee: H. E. Haferkorn, 1891). [!!!Page Number]

Figure 10. The portraits of four doctors presented in the program of the American International Congress on Tuberculosis. The American International Congress on Tuberculosis. (New York: Medico_Legal Journal, 1904). [!!!Page Number]

Figure 7. An image of the chemistry room in the City of Chicago Municipal Tuberculosis Sanatarium. [!!!Doublecheck this] City of Chicago Municipal Tuberculosis Sanatarium Bulletin. (1925-26). [!!!Page Number]

Figure 8. A photograph of patients and caregivers on the porch of the Muskoka Free Hospital. Brandt, Lilian. A Directory of Institutions and Societies Dealing with Tuberculosis in the United States and Canada. (New York: , 1904).

Figure 9. A photograph of patients at Trudeau’s Adirondack Cottage Sanatorium taking the rest cure. Pamphlets Homeopathic. (1899-1909). [!!!PageNumber]

The varying visual subjects, then leads to many kinds of seeing, which deserve their own inspections and interrogations. This would be an entirely different dissertation, so I am only able to gesture toward these phenomena. Instead, this chapter attempts to do two things. First, it will give a sense of the historical context in America around tuberculosis at the turn of the twentieth century through an examination of the various kinds of images printed in the corpus. This can give a glimpse into broad trends in the visual culture, and examine how visuality was constructed outside of the context of medical research. What will become apparent is a slippage between categories, partly due to a fuzziness in intended audience, and partly between what these medical institutions, authors, and publishers thought they should show. Second, developing from this, this chapter will leverage this collection of images to describe a much wider field than usually imagined by media studies scholars. Just as film studies can be broadened by an interest in the non-theatrical uses of cinematic technologies9, and has seen scholars of these kinds of films interested in health and science,10 media studies can benefit from a shift in focus and material. This chapter provides a bird’s eye view of the kinds of different visual cultures which intersect and contest meanings around health and wellness. It is too simple to limit health to a discursive top-down, doctor-centric view, and too simple to see patients, caretakers, and institutions in such a narrow view.

-

Mirzoeff, Nicholas. An Introduction to Visual Culture. London & New York: Routledge, 2000. 13. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Crary, Jonathan. Techniques of the Observer: On Vision and Modernity in the Nineteenth Century. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1992. 5. ↩

-

Shapin, Steven. Never Pure: Historical Studies of Science as If It Was Produced by People with Bodies, Situated in Time, Space, Culture, and Society, and Struggling for Credibility and Authority. Baltimore, Md: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010.

[!!!Check which chapter] ↩

-

A good example would be the reliance on rest in the American context and the reliance on work in the UK. See: Bryder, Linda. Below the Magic Mountain: A Social History of Tuberculosis in Twentieth-Century Britain. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1988. ↩

-

Feldberg, Georgina D. Disease and Class: Tuberculosis and the Shaping of Modern North American Society. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1995. ↩

-

Miller’s work was bolstered by a commitment to visual rhetoric, and regularly featured detailed illustrations, photographs, as well as images developed to be seen through a stereoscope. ↩

-

Cameron & Long. TB Medical Research. 7. [!!!Add Zotero] ↩

-

Quote some stuff from Greg’s class ↩

-

Some books. Include the Oliver Gaychen book and Visual culture ↩