Chapter 1

Section 1.0

Section 1.1

Section 1.2

Section 1.3

I have taken it on myself to make note whenever a certain photograph appears in the tuberculosis corpus. I noticed it first when flipping through one of many pamphlets and books published by Sigard Adolfus Knopf—a prominent doctor and eugenicist, who published many books on tuberculosis and other ailments at the beginning of the twentieth century. Knopf’s work over this period involves a lot of reuse of the same materials—the same equipment to prevent the spread of tuberculosis (fig 1), and the same illustrations showing exercises to help against the disease (fig. 2). This image extends beyond Knopf’s ouvre and is instead something that appears scattered among a number of sources: it is a photograph of one of the lodges at the Adirondack Cottage Sanatorium (fig. 3 & <$n:figure2:!!!FINDONE)).

Figure 1. [!!!Add this]

Figure 2. [!!!Add this]

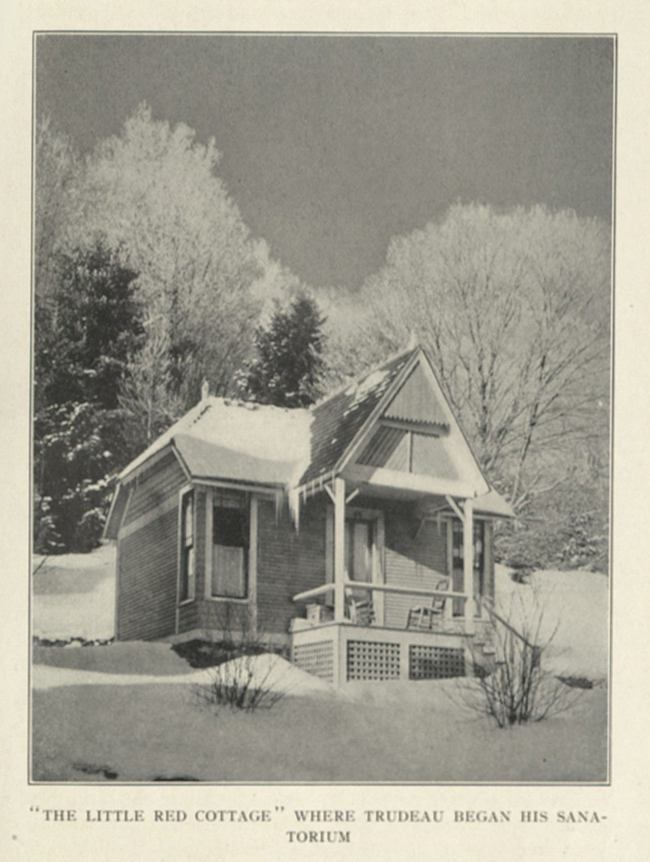

Figure 3 From Knopf_1922_0001.“The Little Red Cottage” which is reproduced in S. A. Knopf’s book might be the most commonly reproduced image in the tuberculosis corpus. Image courtesy of the New York Academy of Medicine.

Find some more.

“The Little Red Cottage” was both an advertisement for a sanatorium and a landmark of historical importance: it signals the historic rise of the sanatorium movement in the United States as well as presents an example of its facilities. Images like it also took up an unexpectedly large number of the total images in the tuberculosis corpus. [!!!ADD DATA!!!] Images like this one populated directories for the tuberculous to find care, they showed up in public journals, and they were included in scientific publications as well. The sanatorium loomed large in the cultural understanding of the disease at the turn of the twentieth century, and the visual representation of this phenomenon requires some discussion.

Trudeau had modelled the Adirondack Cottage Sanatorium on the work of previous medical men, most commonly citing Hermann Brehmer’s Heilanstalt as inspiration. Translated from the german, heilanstal** means ‘healing place’, a linguistic link which Trudeau maintained in the English language development of the concept. Sanitarium draws from the Latin *sanare—to heal—and sanitas—healthy.1 The sanitarium drew also on a longer history of the health spa, and even prior to Brehmer’s institution, other medical practitioners like [!!!that one british doctor] opened similar institutions in the early nineteenth century. [!!!add in a few sentences on the health spa]

Where Trudeau’s sanatorium is a central player in the discourses of this dissertation, it was not the only institution operating in the United States. Trudeau’s model of the sanatorium—as a center for healing and research‚ was not adopted by the majority of the health care institutions which emerged in its wake. Instead, in the literature, scholars from Saranac Lake (the Adirondack Cottage Sanatorium), New York (where multiple associations like the National Tuberculosis Association were formed and run), Asheville, North Carolina (Winyah Sanitarium ran by the von Ruck brothers), Chicago (the Chicago Municipal Sanatorium), Philadelphia (The Henry Phipps Institute), Colorado (the National Jewish Hospital for Consumptives, and also sanataria run out of Colorado Springs), California (The Pottenger Sanatorium), and Baltimore (Johns Hopkins University), wrote a large amount of the published research. There were more than 100 sanataria [!!!find a source to get a specific number] operating in the United States, but a relative few were publishing scientific research on the disease, meaning that scientific output was a secondary concern to those operating these institutions. Even those institutions which were publishing regularly, many research scientists like H. J. Corper, who worked out of the Chicago Municipal Sanatorium and, later, the National Jewish Hospital for consumptives, published bacteriological studies that relied on animal subjects.

In the American west, many of these institutions were part of an explicit or implicit move to bring people into the area. Los Angeles’ history with the tuberculous sick began with an interest in the 1880s to court and lure patients into the city. It was argued in advertisements that the sick might benefit from the city’s naturally temperate climate. In the decades, following, however, the city and its inhabitants began to see the chronically ill as a detriment, and practiced multiple campaigns to both drive the sick from the county, as well as actively deny the right for tuberculous people to move there.2 In many cases, the promise of a climactic cure meant that patients who could not afford treatment would still make their way to drier regions. In Colorado Springs, for example, the tuberculous sick caused a similar anxiety for locals as it had in Los Angeles.3

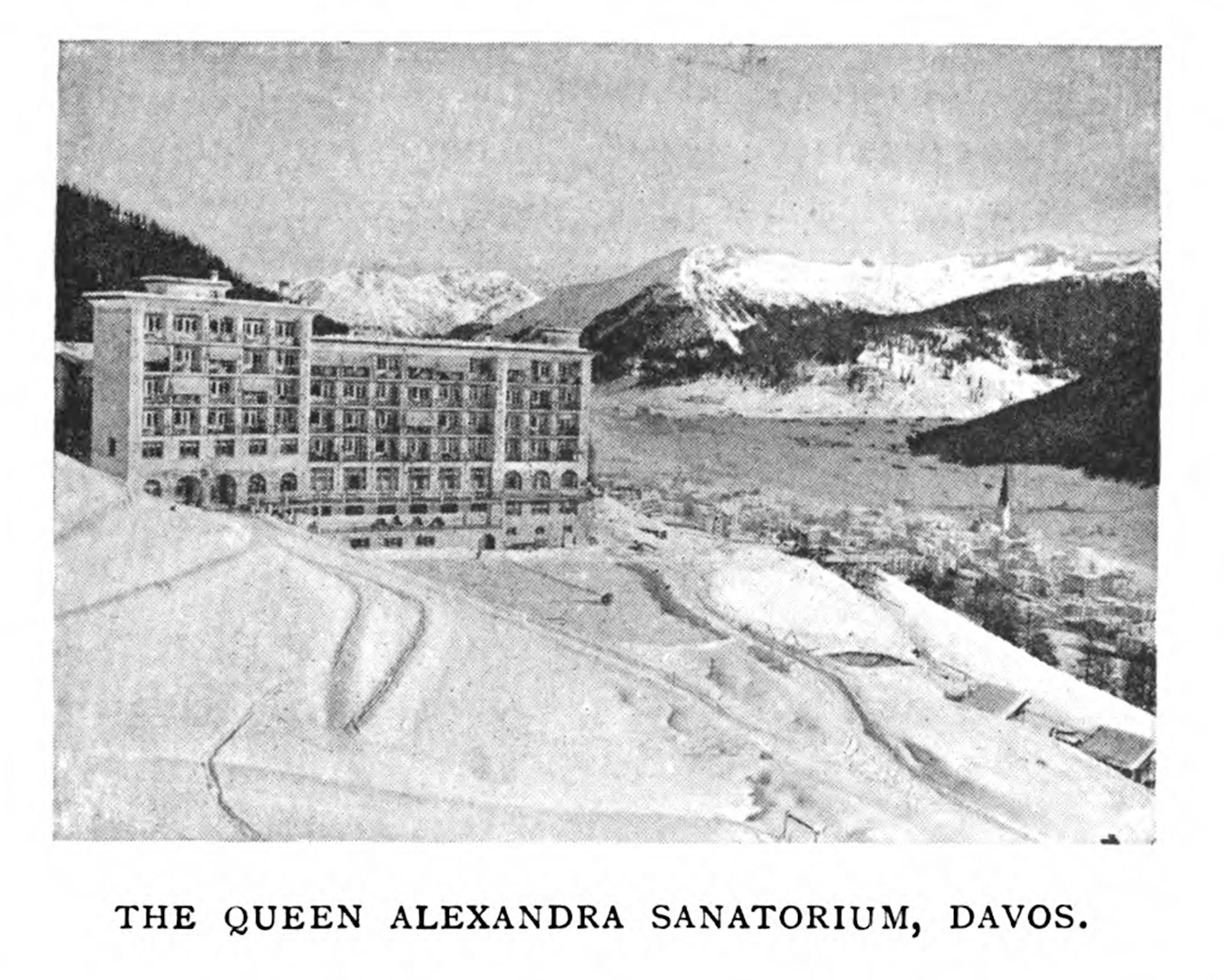

The sanatorium was a prominent, but not singular, actor in health interventions against tuberculosis. The hospital and dispensary also played pivotal roles at this period, in both treating, but also educating tuberculous patients (1.3.2). It did however symbolize the broader anti-tuberculosis movement, driven in part by the influence of Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain, which depicted sanatarium treatment at Davos, Switzerland (fig. 4 & 5).4

Figure 4. The Queen Alexandra Sanatorium in Davos, Switzerland was a prominent institution in the European approaches to tuberculosis. Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain is modelled on this kind of idyllic health resort. From, The British Journal of Tuberculosis. (London: Ballière, Tindall & Cox, 1911), 46.

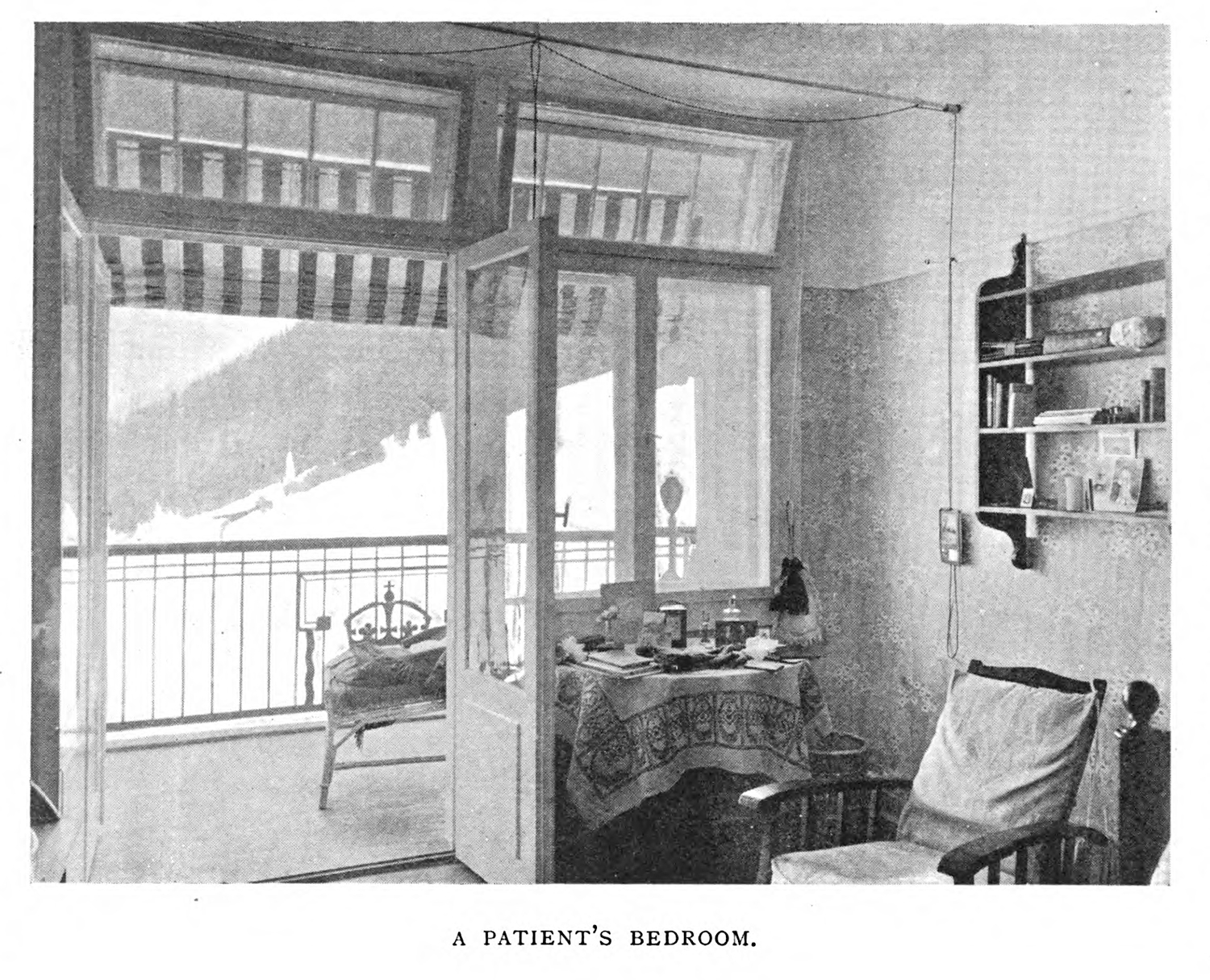

Figure 5. A glimpse into the private room of a patient at the Queen Alexandra Sanatorium in Davos, Switzerland. From: The British Journal of Tuberculosis. (London: Ballière, Tindall & Cox, 1911), 48.

What should be remembered, however, is that while the spectre of the sanatarium as it is imagined by authors, doctors, patients, and the general public looms large, it is not a monolith. My interest for this section is to parse how the sanatorium is imagined through its visual artifacts. What will start to become aparent, is that these visual materials are closely linked to the kinds of audiences to which sanatorium operators were speaking, and the contexts in which they were speaking.

Importantly, for this section, is that I am focusing on how the sanatorium is projected out in the literature. The institution itself was both a place where patients could be healed, but also was designed in such a way as to facilitate healing. I will go into more detail as to how the sanatarium was imagined to actively cure later in this chapter (1.4.1). It was not imagined as a ‘non-place’, to borrow Marc Augé’s popular description of transitory spaces like hospitals, hotels, and train stations.5 Of course, how it was imagined and how care was actually practiced is very different,6 and the tensions between the projected and constructed sanatorium image and the other scientific, epistemic, and political cultures which these visual representations maintained and reproduced, can help examine the dichotomy between an institution of care and an institution of anonymity (3.x.x [!!!asection about death culture critiques of medicine]).

-

Daniel, T. M. “Hermann Brehmer and the Origins of Tuberculosis Sanatoria.” International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease 15, no. 2 (2011): 161–62. ↩

-

See: the book on LA TB. ↩

-

Golden Pill Book. ↩

-

There is much written about this novel, as it is a significant text in modern German literature. This topic, however, is beyond the scope of the current project. ↩

-

Augé mentions the hospital directly in his definition of non-place: “A world where people are born in the clinic and die in the hospital. . . a world thus surrendered to solitary individuality, to the fleeting, the temporary and ephemera, offers the anthropologist (and others) a new object, whose unprecedented dimensions might usefully be measured before we start wondering to what sort of gaze it may be amenable” (78).

Augé, Marc. Non-Places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity. Translated by John Howe. London & New York: Verso, 1995. ↩

-

Bryder, Linda. Below the Magic Mountain: A Social History of Tuberculosis in Twentieth-Century Britain. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1988.

[!!!Add Toronto Sanatarium text too!] ↩