Chapter 1

Section 1.0

Section 1.1

Section 1.2

Section 1.3

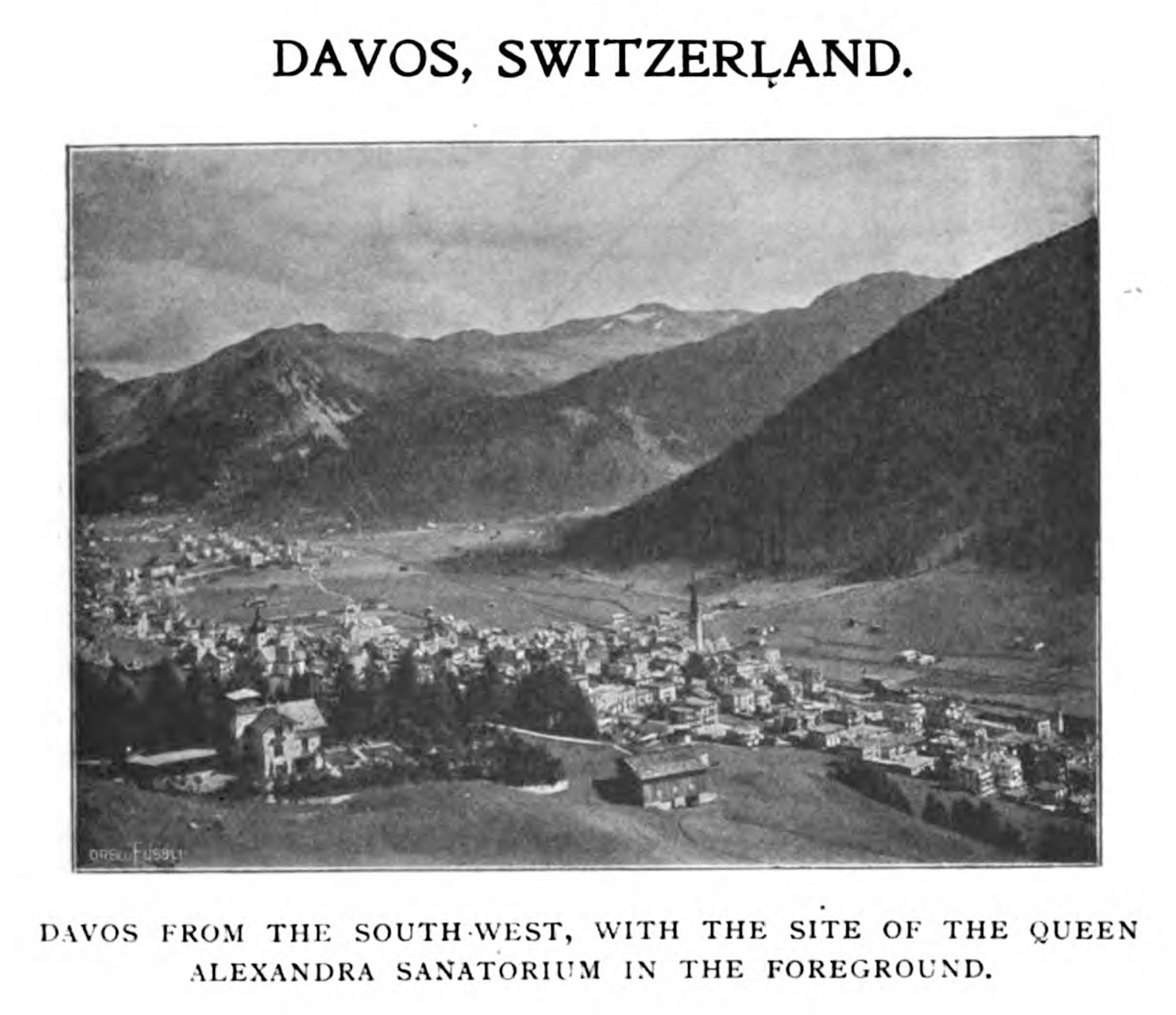

In addition to regular spotlights of local sanataria, the British Journal of Tuberculosis reserved space for a section titled “Health Stations”. Looking further than the national scale of the other feature, “Health Stations” promoted the destination spas on the continent (figs. 1 & 2). The way the author describes Davos, in the first issue of the journal, contrasts to the way the King Edward VII Sanatorium, in how amenties are disregarded for climatic qualities:

The following factors are concerned:

-

The Rarity of the air—mean barometric pressure 632 milimetres.

-

The low temperature, 37° F. being the annual mean, about that of St. Petersberg or Iceland. The ground is covered with snow generally from mid-November to mid-April. Summer nights are cool, rarely above 55° F.

-

The intensity and duration of the solar radiation. The summer sun loses less than half its heat in mid-winter. January has 55 per cent of the possible sunshine.

-

The Dryness of the air, which is hense so bad a conductor of heat as to make even intense cold but little felt. The mean total rain and snowfall is equivalent to 35 1/2 inches of water.

-

The purity of the atmosphere from suspended particles, amounting in winter to a complete absence of dust.

-

The absence of cloud and mist : in an average winter there are 102 fine days, 22 medium, and 58 bad.

-

The absence of wind : from December to March there is generally an absolute calm on fine days. Eighty-five per cent. of the wind obersvations give N.E.—i.e., the south balconies are in sun, but out of the wind.

-

The high content in the air of radio-active substance and of electric potential.

Figure 1. A photograph showing the town of Davos, Switzerland. The British Journal of Tuberculosis. (London: Ballière, Tindall & Cox, 1907), 65.

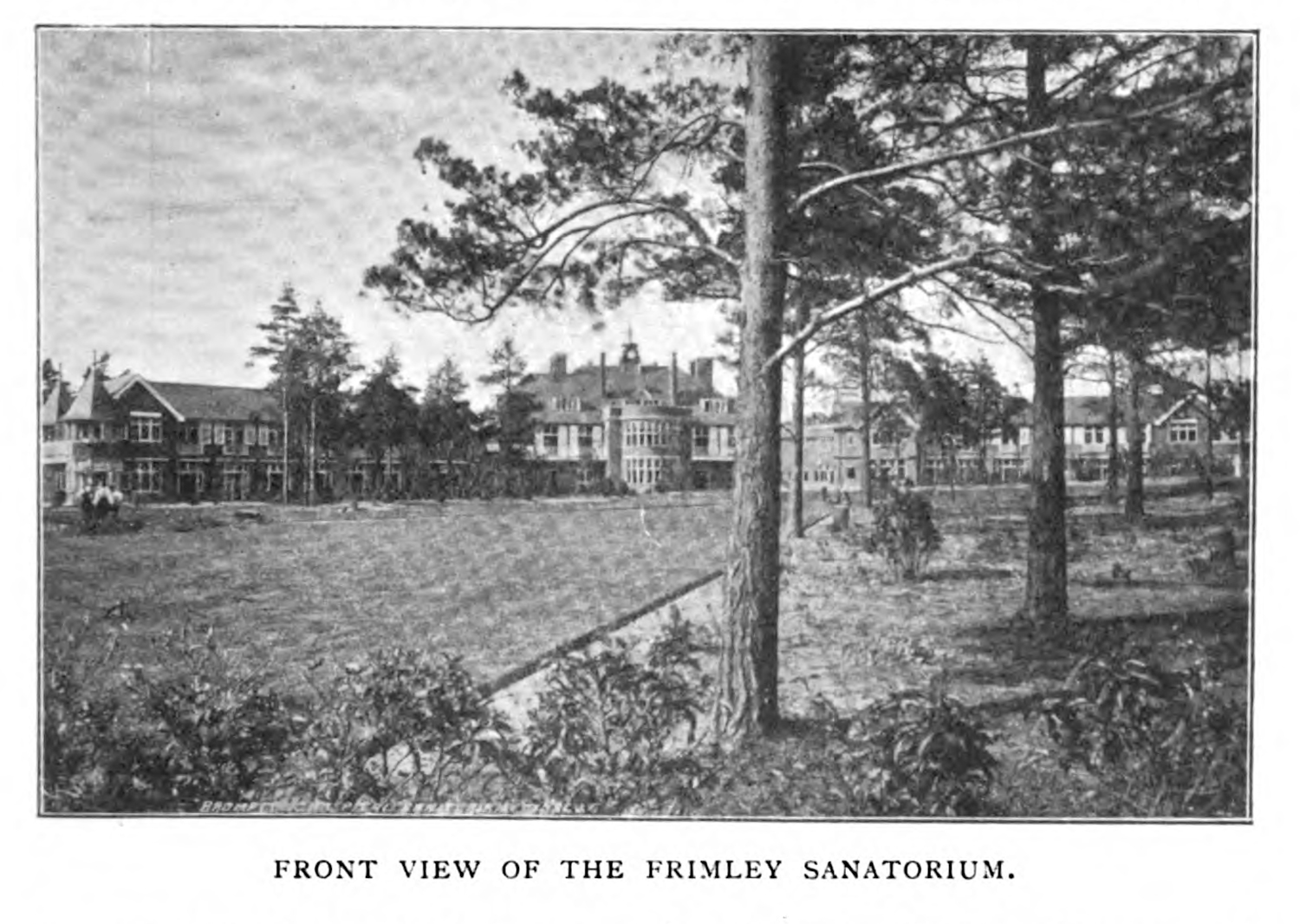

Figure 3. An exterior view of the Frimley Sanatorium. The British Journal of Tuberculosis. (London: Ballière, Tindall & Cox, 1907), 66.

The way Davos is described in this lengthy passage points to some of the scientific discourses surrounding the treatment of tuberculosis. At the turn of the twentieth century, scientific arguments concerning the benefits of moving to a climate that was inhospitable to the disease,were giving way to a more general notion of getting patients out of poorly ventilated spaces, out of dirty cities, and out of crowds. James Alex Lindsay’s 1887 monograph describes this as much:

[Block quote]The old notion that the air in certain regions exercised a sort of local healing influence upon the damaged lung tissue is without foundation. There is, in fact, no ideal climate for consumption ; no happy Hygeia to which the consumptive can repair and draw in healing influences with every breath.1

For Lindsay, the climatic treatment functions on a binaristic view of localities: he imagines the places where tuberculous patients live as crowded, dank, unhealthy places. Patients undergoing climatic treatment move from “comparatively sunless and depressing climates”, from “crowded populations and vitiated air”, from “the injurious influence of damp soil and of imperfect sanitation”, to give “the patient the great boon of change—change of air, change of diet, change of scenery, change of daily routine, change involving the abandonment of many an injurious habit which has long been the secret minister of disease.”2

Twenty years later, in a summary of climatic approaches to care prepared by F. C. Smith for the United States Surgeon-General, argued the same:

[Block quote]Very much is said concerning the choice of locality in the different stages of pulmonary tuberculosis, but when the disease is limited to an apex, in a man of fairly good personal and family history, the chances are that he may fight a winning battle if he lives out of doors in any climate, whether high, dry, and cold or low, moist and warm.3

[!!!Add some description of this section]

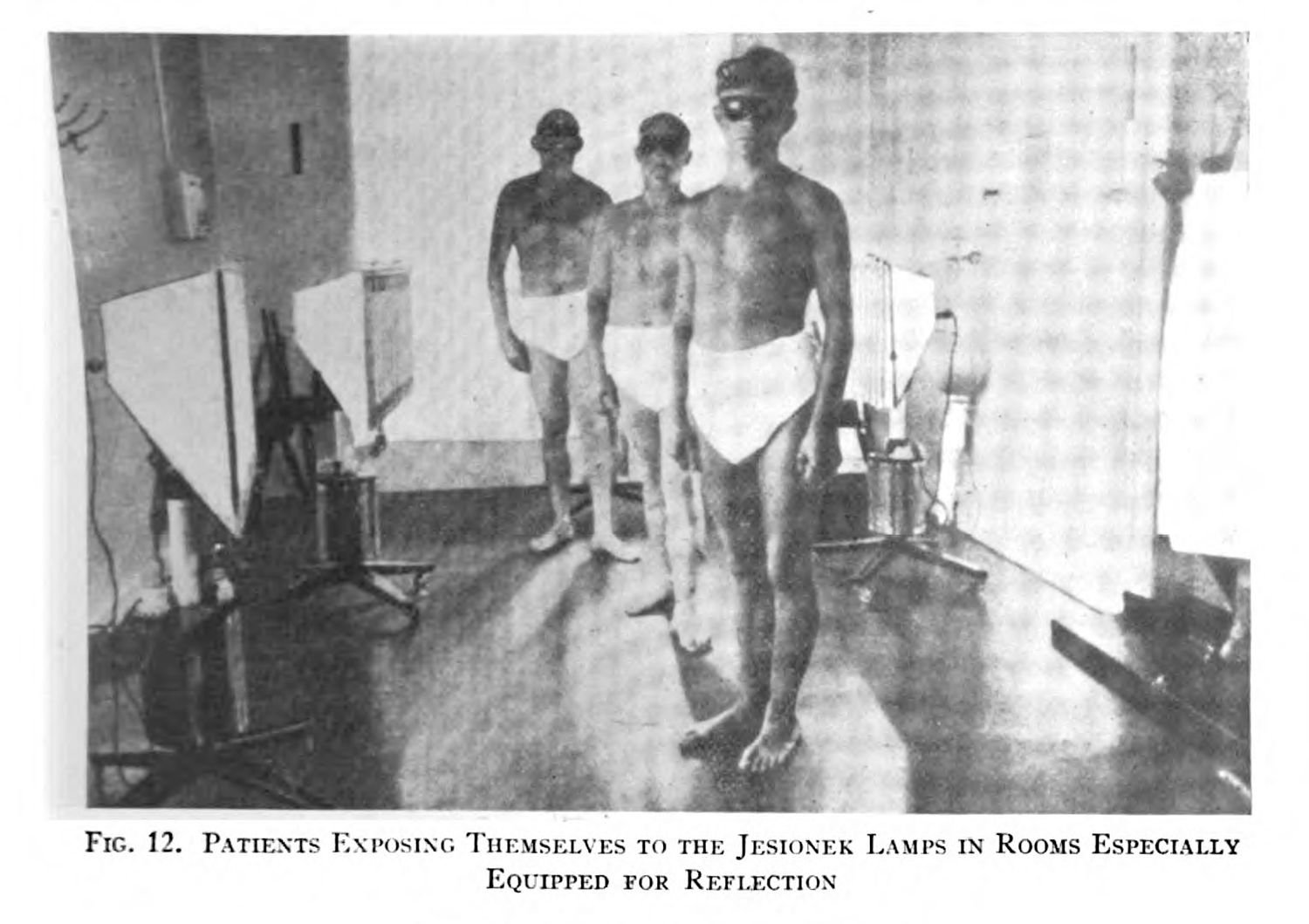

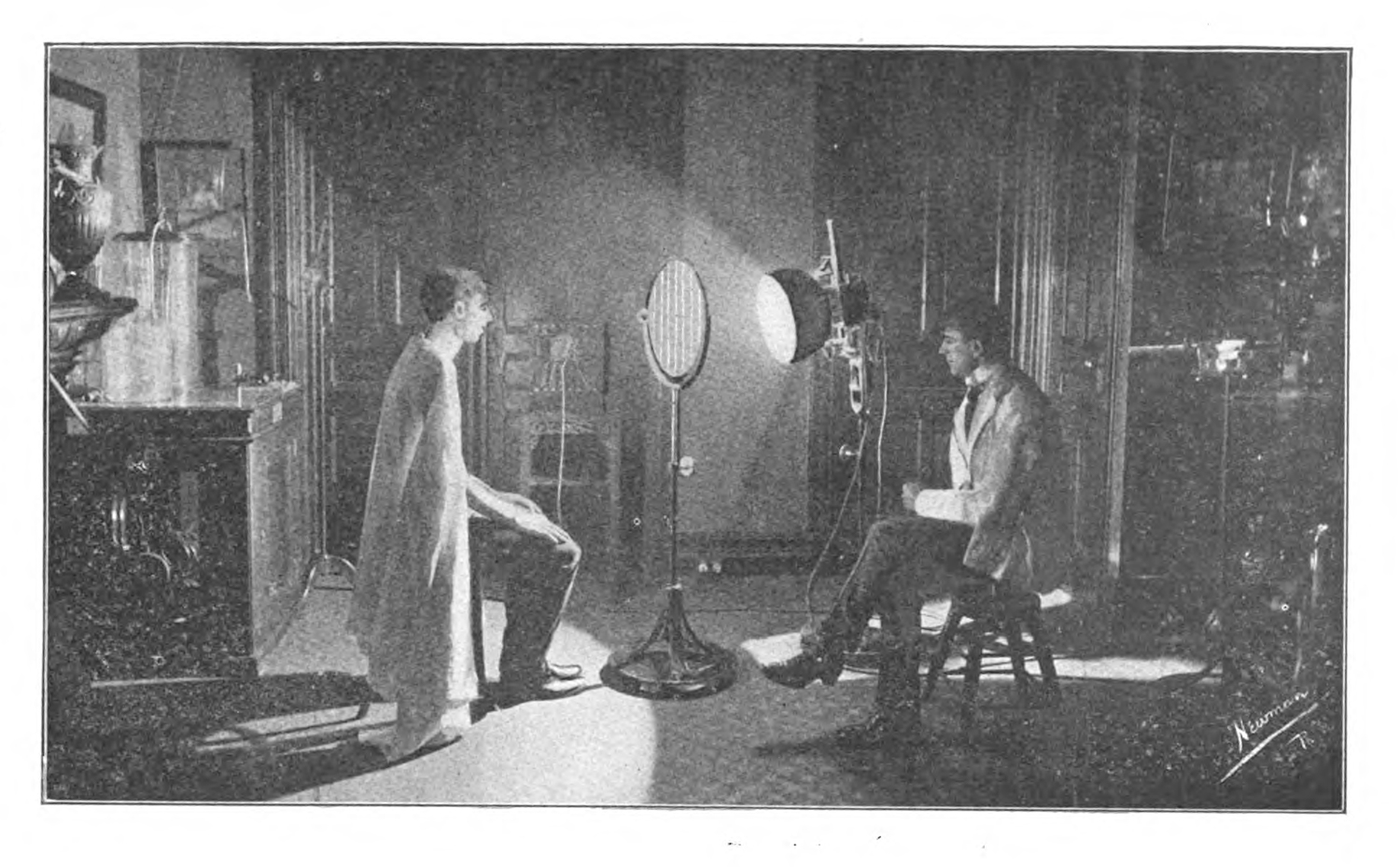

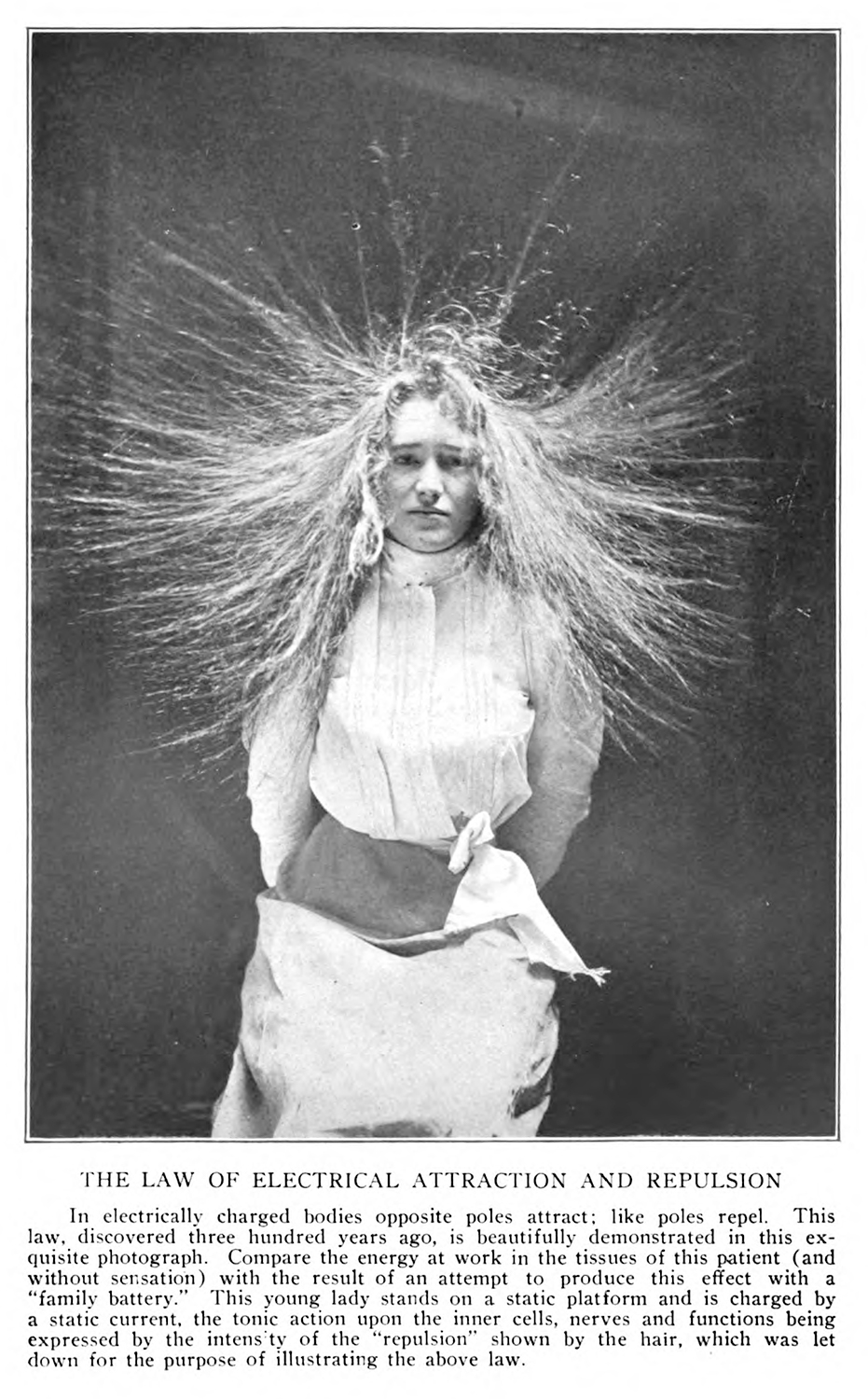

The description of Davos in The British Journal of Tuberculosis articulates a dream climate: one which plays for the lay public on popular imaginations of cure and the quantifiable qualities that prove it a better environment than the industrialized city. At the same time, it evokes the popular, but poorly documented, phototherapy (figs. 4 & 5) and electrotherapy (fig. 6), as well as the use of radium as a curative agent.4

Figure 4. An example of phototherapy. Mayer, Edgar. “Sunlight and Artificial Light Therapy in Tuberculosis: A Critical Review.” Edited by Edward R. Baldwin, Lawrason Brown, M. J. Rosenau, H. R. M. Landis, Paul A. Lewis, and Borden S. Veeder. The American Review of Tuberculosis 5 (1922-1921), 111

Figure 5. An example of phototherapy. A shrouded patient stands in front of a powerful light while a doctor looks on. Bleyer, J. Mount. “Light—Its Therapeutic Importance in Tuberculosis as Founded upon Scientific Researches.” The Journal of Tuberculosis, October 1902, 77.

Figure 6. An example of electrotherapy. A woman sits with her arms crossed and her hair standing up from the electric current. [!!!AddCitation]

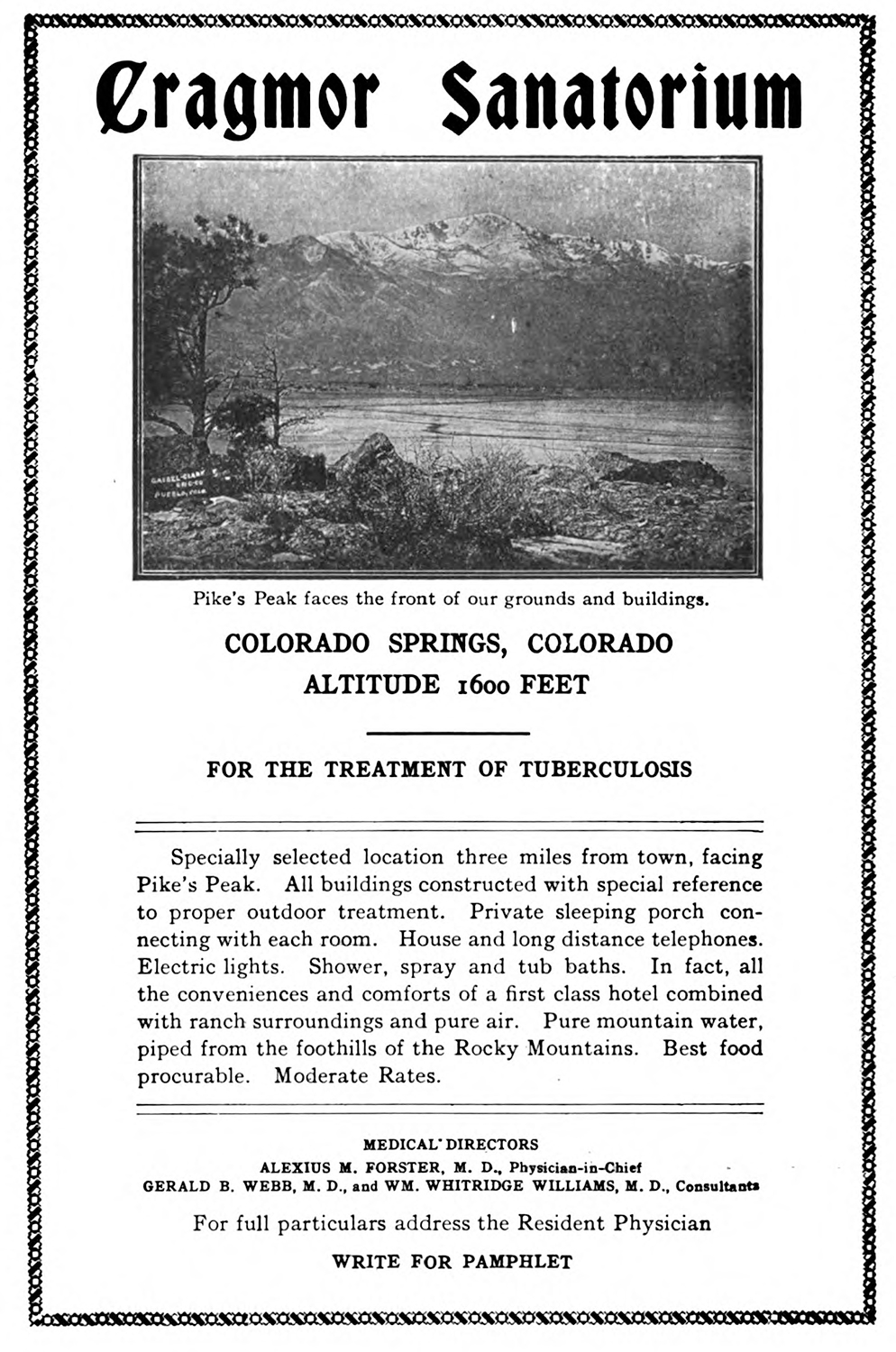

So there is a contradictory practice: a reaching by both the health resort and the published discoures around it to prove a specific place as unique, special, exemplary. Climate remained this key selling point. This could be implicit, as with the evocation of the Sierra Madres by Francis Marion Pottenger’s sanatorium (fig. 7), It could also be explicit, as the Cragmor was advertised, where the image of any facilities are eschewed for a landscape with Pikes Peak in the distance (fig. 8.

Figure 7. An add for Francis Pottenger’s Monrovia sanatorium. [!!!Add Citation]

Figure 8. An add the Cragmor Sanatorium. [!!!Add citation].

These last ads provide a glimpse into some other aspects of the broader tuberculous culture of the period. They maintain a kind of extravagance, reserved for the upper class with “all the conveniences and comforts of a first class hotel” (1.2.5). They provide exceptional care because of a laboratory on site (2.2.0). They provide privacy, and also community (1.2.4). They imagine a kind of relationship between the subject and their social and material environment that is antithetical to the world that the climate cure describes as the root of the disease.

-

Lindsay, James Alex. The Climatic Treatment of Consumption: A Contribution to Medical Climatology. London: MacMillan and Co., 1887, 20. ↩

-

Lindsay, James Alex. The Climatic Treatment of Consumption: A Contribution to Medical Climatology. London: MacMillan and Co., 1887, 21. ↩

-

Smith, F. C. The Relation of Climate to the Treatment of Pulmonary Tuberculosis. Public Health Bulletin 35. Washington: Government Printing Press, 1910, 5. ↩

-

For each of these treatments see: On phototherapy: Weinzirl, John. The Action of Sunlight Upon Bacteria with Special Reference to B. Tuberculosis. Chicago: The Journal of Infectious Diseases, 1907; Mayer, Edgar. Clinical Application of Sunlight and Artificial Radiation: Including Their Physiological and Experimental Aspects with Special Reference to Tuberculosis. Baltimore: The Williams & Wilkins Company, 1925.

On electrotherapy: Monell, S. H. Electricity in Health and Disease. New York: McGraw Publishing Company, 1907; Mayer, Edgar. “Sunlight and Artificial Light Therapy in Tuberculosis: A Critical Review.” Edited by Edward R. Baldwin, Lawrason Brown, M. J. Rosenau, H. R. M. Landis, Paul A. Lewis, and Borden S. Veeder. The American Review of Tuberculosis 5 (1922-1921), 75-157; Bleyer, J. Mount. “Light—Its Therapeutic Importance in Tuberculosis as Founded upon Scientific Researches.” The Journal of Tuberculosis, October 1902, 1–80.

On radium treatment: Wickham, Louis, and Paul Degrais. Radium as Employed in the Treatment of Cancer, Angiomata, Keloids, Local Tuberculosis and Other Affections. London: Adlard and Son, Bartholomew Press, 1913.

A mix of these methods can also be seen in Gibson, Jefferson Demetrius. Handbook of Pulmonary Tuberculosis: Its Diagnosis, Prognosis, Prevention and Treatment. Denver: The Denver Scientific Publishing Co., 1920. ↩