Chapter 1

Section 1.0

Section 1.1

Section 1.2

Section 1.3

The sanatorium in this period was stratified along class and race. In all of the images supplied earlier in this chapter, I have not included any images of patiends who may be read as Black. The health system in America in this period was marked by racial and national boundaries: New York’s Jewish and German hospitals [!!!Checkforthename] catered to a particular racialized patient demographic. It is also a limitation, as a scholar from the early twenty-first century, as to my ability to read (as would be trained in an explicitly racially segregated and deeply eugenicist nation such as the United States at the turn of the twentieth century1) how a subject may be offhandedly raced as Irish, Italian, or otherwise non-white. The ambivalence of doctors in the corpus to Black subjects in particular may be a gap in regards to the mateirals available in online archives, or a methodological issue regarding the selections of texts, as at the governmental level care to race becomes more pronounced (1.3.x).2 This gap may also be the result of a concerted effort by Black patients to avoid the same institutions that subjected them to horrific experimentation in the Antebellum period,3 and who regularly looted their graveyards for anatomical material (3.x.x).4

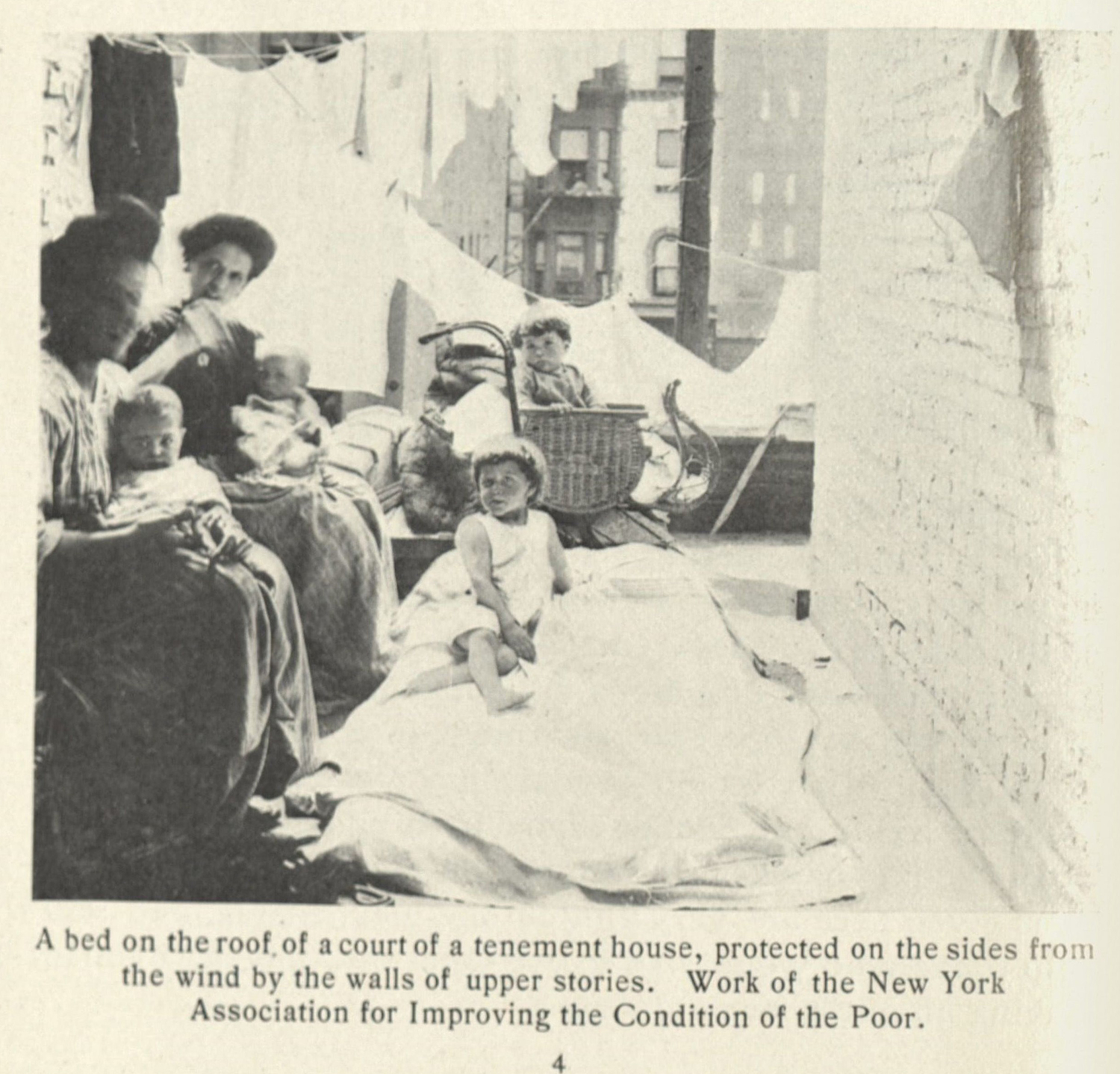

Beyond the racial gap in this research project, there is also a class difference: lower class patients would be treated but always under the judgemental framework of hygiene, which saw patients as being at fault for their unhealthy housing (fig. 1) and disrespectable living habits, and which saw tuberculosis as a preventable disease and, thus, that those who got sick may be partially at fault for their condition. As Linda Bryder reminds us, those researching the disease “showed themselves to be very much a product of the middle-class society from which they came, with its fixed assumptions about the poor.”5

Figure 2. An example of the squalor hygiene activists fought against.

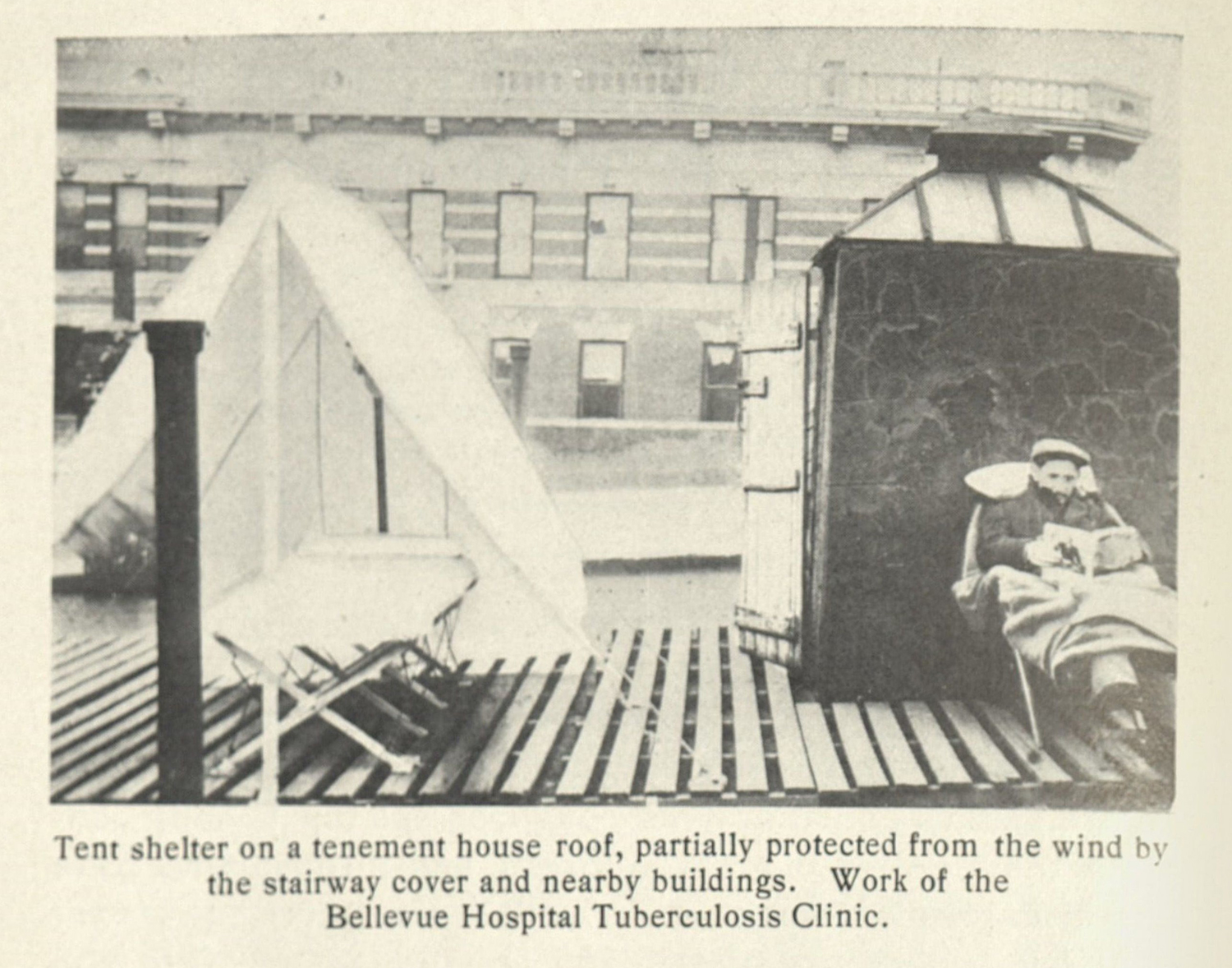

This section will go into some detail as to the separate, but intertwined practices that constituted the hygienic interventions into the disease. Interwoven in the same discourses in the previous section (1.2.0), this section will discuss the various ways the climatic, outdoor life was engaged by urban patients who were too sick to travel or could not afford sanatoria treatment (figs. 3 & 4).

The anxieties about urban spaces were redoubled: the crowded, dusty, squalor of urban living was vilianized, and blamed on those who could afford no better. Institutions like the public sanatorium and the dispensary provided patients with care, while also lecturing the same patients on hygienic principles (such as collecting their sputum and sterilizing it). Some of these institutions, like the Henry Phipps Institute discussed in chapter 3 (3.0.0), were using their position as a public health institution to collect biometric data from living patients and autopsy dead ones (3.0.x). Interlaced with hygiene, the classed and raced qualities of the scientific discourses around tuberculosis gain extra definition.

Figure 3. An example of how urban patients would achieve the open air treatment.

Figure 4. A solution to find open air in crowded New York.

-

I write this as if the United States in 2023 an 2024 is not a deeply segregated, eugenicist country. It is, however, different in forms and structures. ↩

-

Race was especially discussed in the context of more governmental facing documentation. An excellent example of this can be found in Virginia’s 1915 report by the state’s Tuberculosis Commission.

The report involves handwringing as to the health of Black subjects. [!!!PatronizingQuote]. The patronizing tone adopted by the writers of the report is matched by a more self-interested discussion of race. They write, “[s]ince the greatest number of deaths and the greatest number of living cases occur among the negro race, since the relations between the two races are so intimate that a communicable disease affecting the negro must in a grave measure affect the white, since there is not a bed maintained by the State at present for a negro consumptive except in the State Asylum and Penitentiary, we would respectfully urge, for both humanitarian and economic reasons, that a sum of not less than $40,000 be appropriated for the immediate construction of a State sanatorium for the negro consumptive.” The concerns expressed in this document reveal a concern for Black subjects that is entirely bound in a desire to keep the ruling-white class healthy.

State of Virginia. Report of the Tuberculosis Commission of the State of Virginia, 1915. ↩

-

Willoughby, Christopher D. E. Masters of Health: Racial Science and Slavery in U.S. Medical Schools. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2022. ↩

-

Blakely, Robert L., and Judith M. Harrington, eds. Bones in the Basement: Postmortem Racism in Nineteenth-Century Medical Training. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1997; Warner, John Harley. “The Aesthetic Grounding Of Modern Medicine.” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 88, no. 1 (Spring 2014): 1–47;

Sappol, Michael. A Traffic of Dead Bodies: Anatomy and Embodied Social Identity in Nineteenth-Century America. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2002. ↩

-

Bryder, Linda. Below the Magic Mountain: A Social History of Tuberculosis in Twentieth-Century Britain. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1988. 19. ↩