Chapter 1

Section 1.0

Section 1.1

Section 1.2

Section 1.3

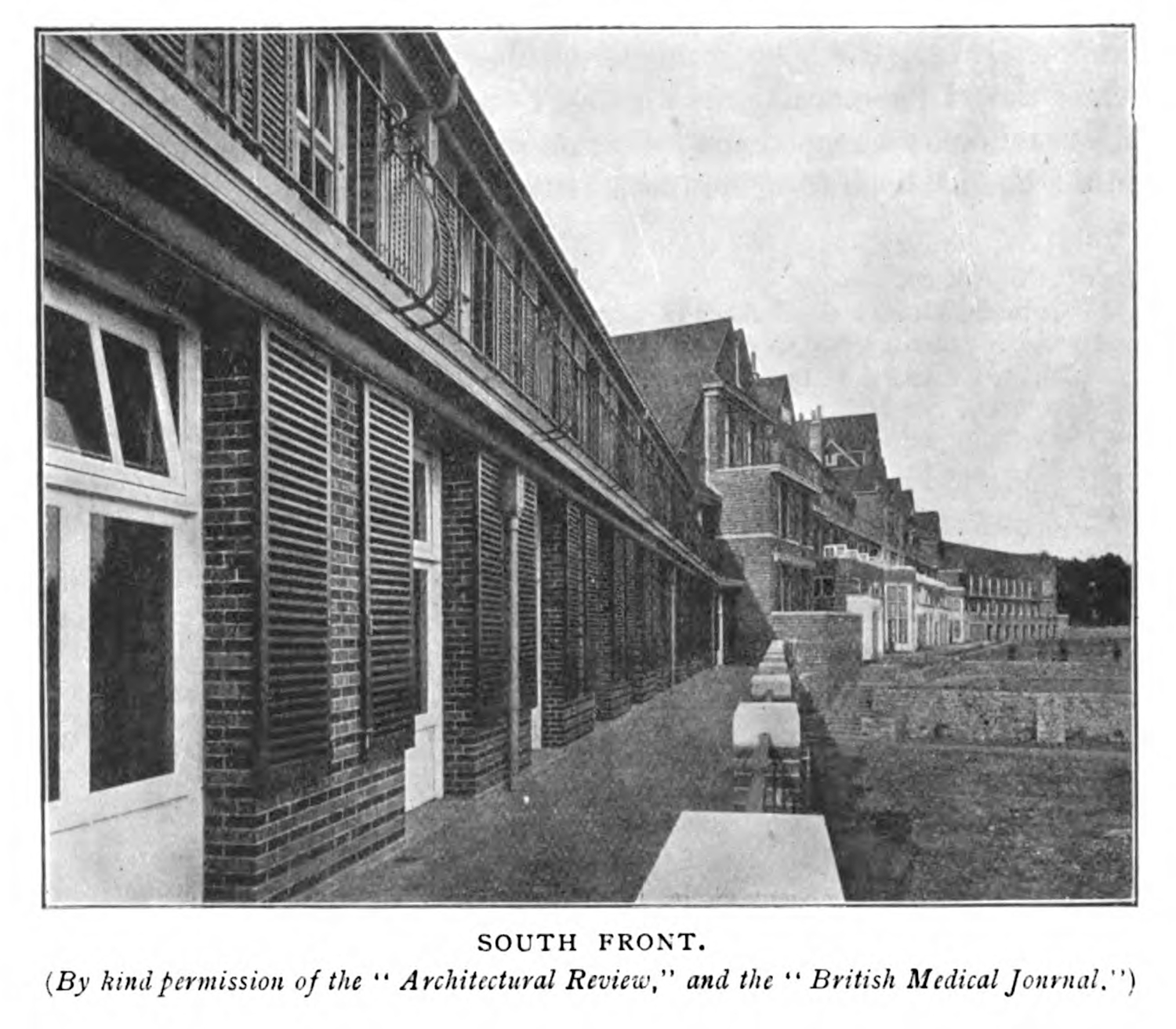

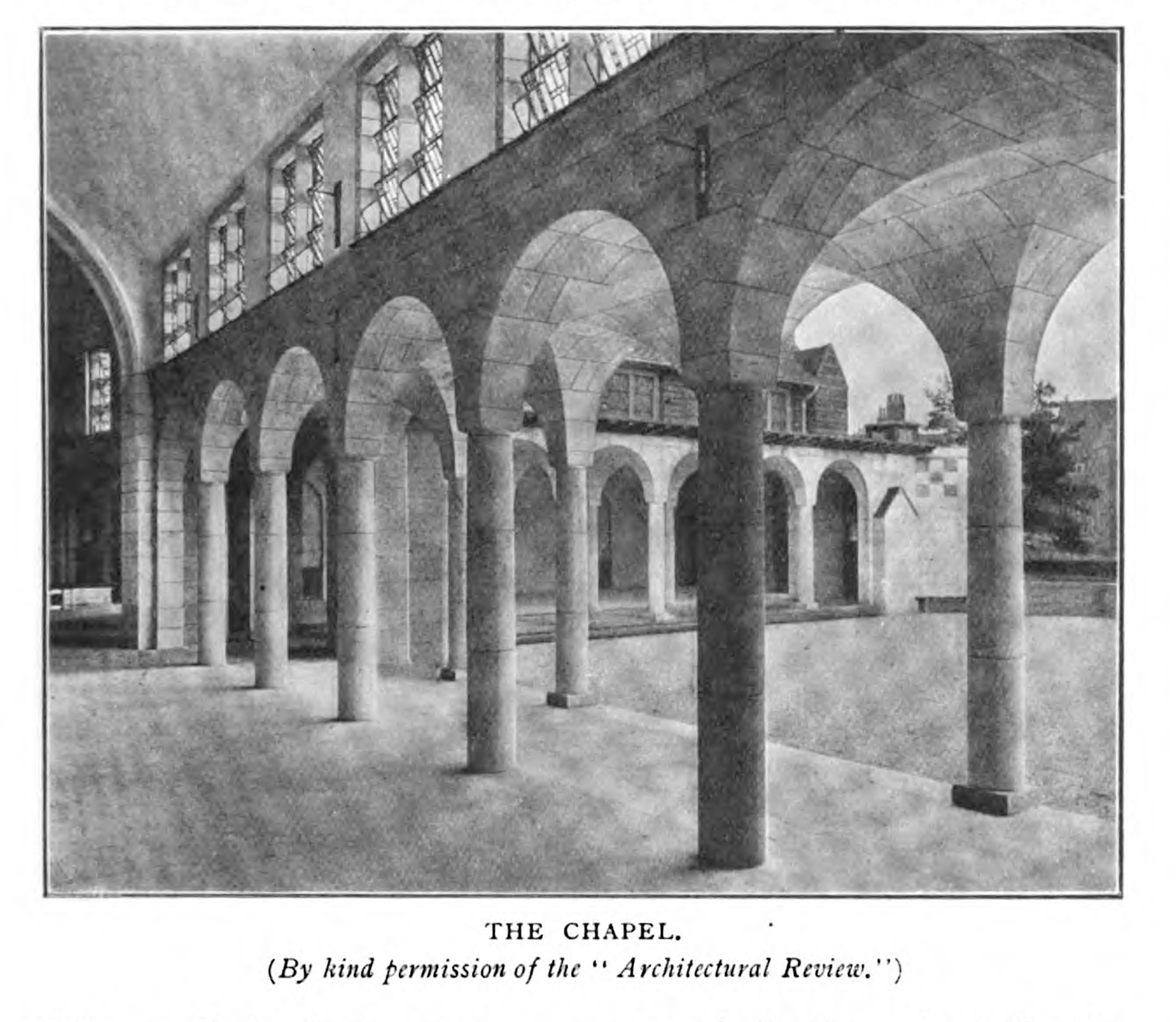

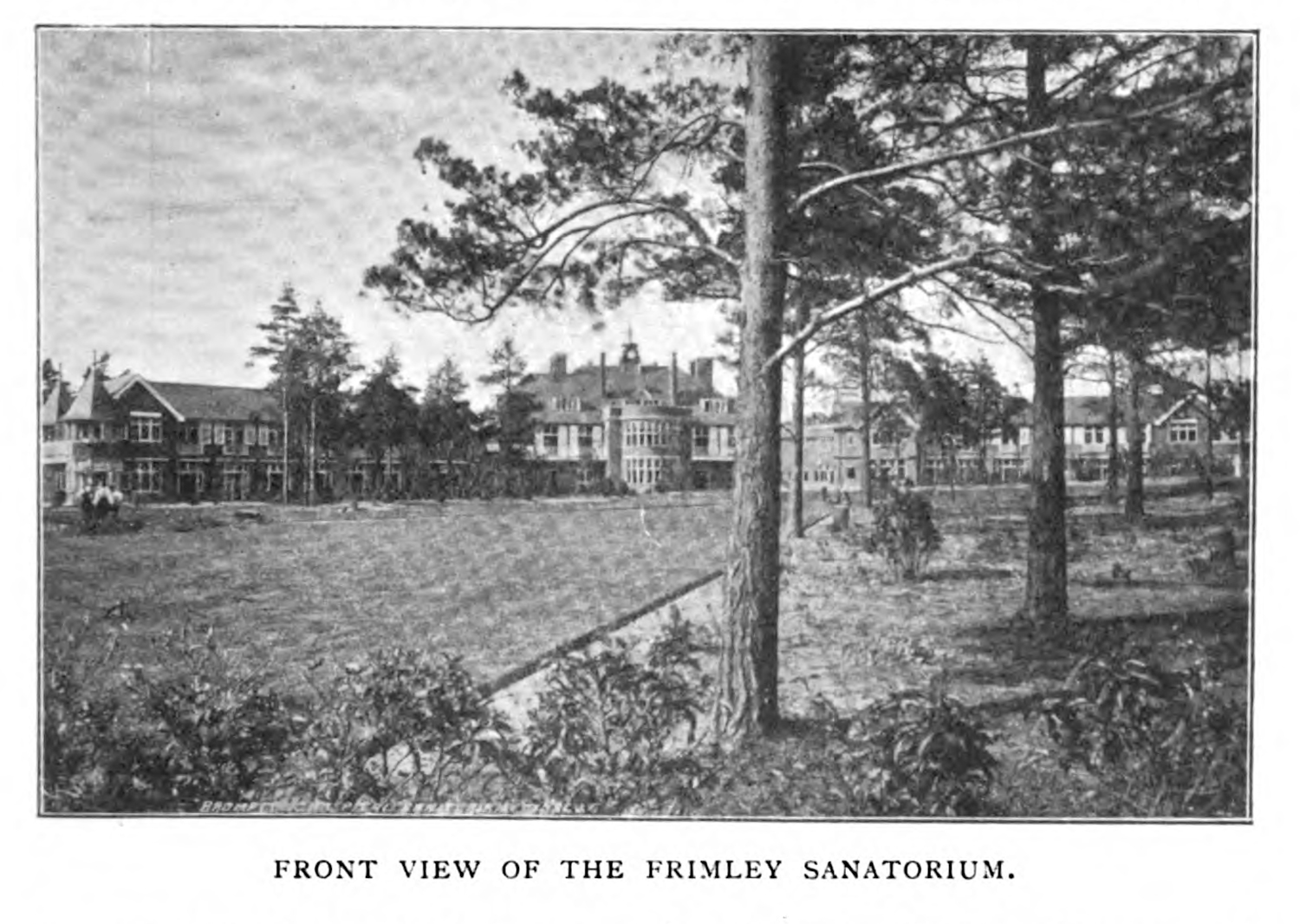

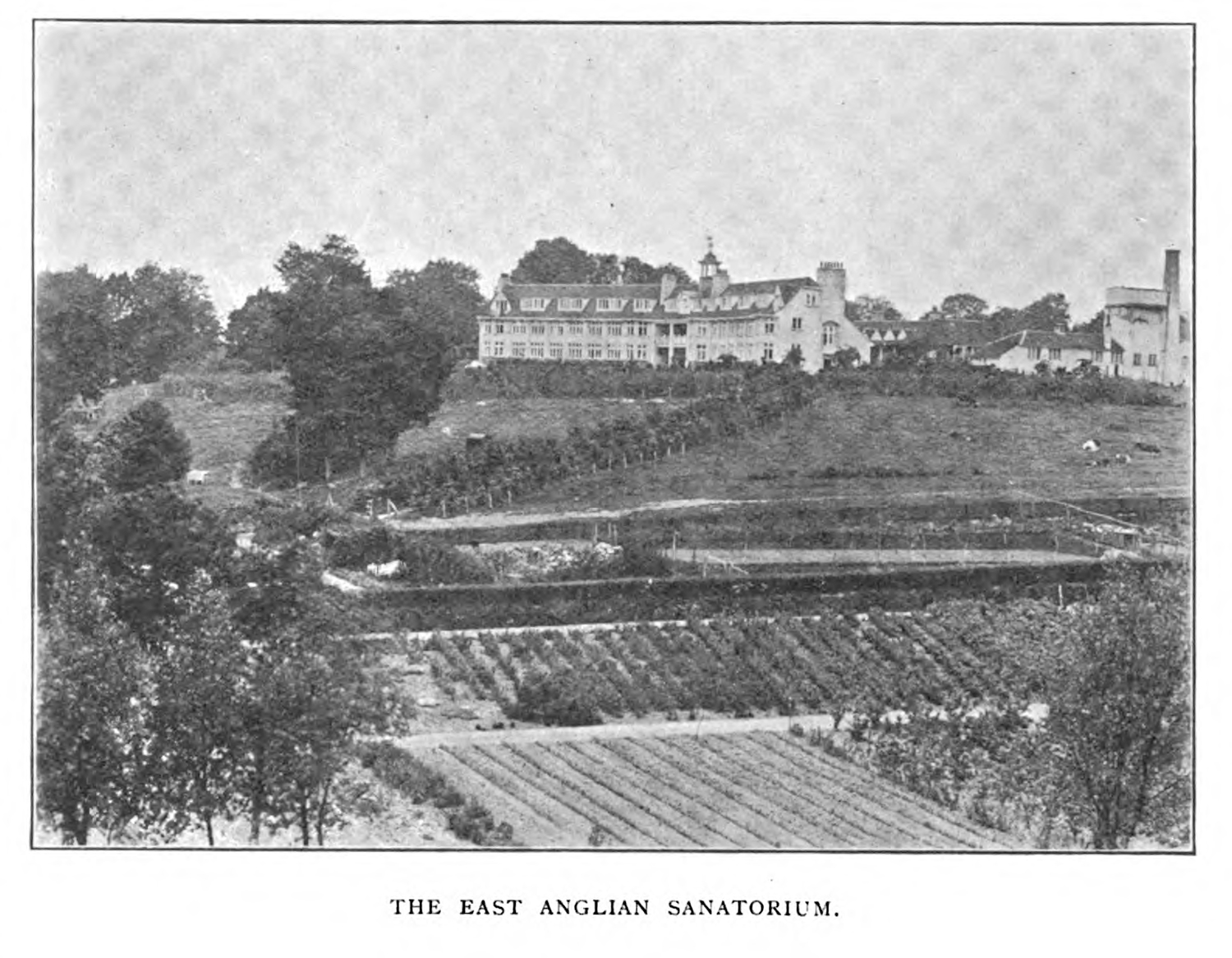

The British Journal of Tuberculosis had a pair of long running series which promoted health institutions in the United Kingdom and Europe. “Institutions for the Tuberculous” spotlighted various health resorts and facilities, providing information about more local hospitals. The first issue of the first volume described the facilities of the King Edward VII Sanatorium in Midhurst (figs. 1 & 2), the Brompton Hospital Sanatorium and Convalescent Home in Frimley (fig. 3), and the East Anglian Sanatorium in Suffolk (fig. <4).

Figure 1. The exterior of the King Edward VII Sanatorium The British Journal of Tuberculosis. (London: Ballière, Tindall & Cox, 1907), 60.

Figure 2. The chapel of the King Edward VII Sanatorium. The British Journal of Tuberculosis. (London: Ballière, Tindall & Cox, 1907) 61.

Figure 3. An exterior view of the Frimley Sanatorium. The British Journal of Tuberculosis. (London: Ballière, Tindall & Cox, 1907), 63.

Figure 4. An exterior view of the East Anglian Sanatorium. The British Journal of Tuberculosis. (London: Ballière, Tindall & Cox, 1907), 64.

For the facilities described “Institutions for the Tuberculous”, time is spent describing the amenities. The King Edward VII Sanatorium is described as having

[block quote]2 hydropathic-rooms, 2 writing-rooms, 100 patients’ bedrooms (50 men and 50 women), with 6 nurses’ kitches, linen-rooms, etc. The patients’ bedrooms measure 13 feet 6 inches by 11 feet 6 inches, and are 11 feet high. The large windows open out on a balcony 8 feet in width.1

These more rote descriptions are matched with descriptions of the dining facilities—“The dining hall is a handsome room, lined with Doulton Carrera ware, the floor being of stone, which can be heated from beneath”2—and description of the institution’s research facilities—“The pathological block consists of a post-mortem-room and thee well-appointed rooms for pathological and research work. Researches which have a direct bearing upon the treatment of consumption will form an important feature of this department.”3 In a journal that aims toward a (mostly) academic, scientific audience, there is a certain strangeness to the way the facility is described. It reads more like an advertisement.

The King Edward VII Sanatorium presented itself in such a way because it was unlike other institutions, because as Vincent Y. Bowditch states in a puff piece on British sanatoria for The Journal of Outdoor Life, “the sanatorium is not a charitable institution in the strict sense of the word, it being the wish of King Edward that wealthy patients should be accommodated as well as other less well-to-do people.”4 With rooms running as much as five guineas (or around $26) a week5 and costing as little as two pounds two shillings (or around $10.50) for a week of care,6 the sanatorium was hoping to care for middle to upper class patients.7 As treatment was costly, the luxurious framing helped sell the sanatorium to the journal’s audience (doctors and medical practitioners) how the environment might benefit the tuberculous patients those doctors would encounter and treat. The entries for “Institutions for the Tuberculous” read as ways for the professional practitioners to learn about potential facilities to be sent, with brief descriptions of the amenties which could be used to persuade a sick patient to go there.

It was also likely that patients who were sick with the disease, or families of those who were sick, would look to the quasi-advertisements of sanatoria published in medical journals, or in collected books of sanatoria like the Hand Book of Help for Persons Suffering from Pulmonary Tuberculosis (Consumption) Directory of Tuberculosis Hospitals Sanatoria and Clinics published in 1915 by New York City’s Department of Health or Lilian Brandt’s 1904 book A Directory of Institutions and Societies Dealing with Tuberculosis in the United States and Canada. Brandt, writing in the introduction to the latter monograph, says that the book was “designed, first, to serve as a guide to the physicians and friends of consumptives, whether poor or well-to-do, by furnishing accurate information in regard to existing institutions”.8 Many of the images in the corpus [!!!taggedphotographarchitectural] come from these kinds of publications, which are not scientific but speak to an audience to whom practiticing doctors were a main constituent.

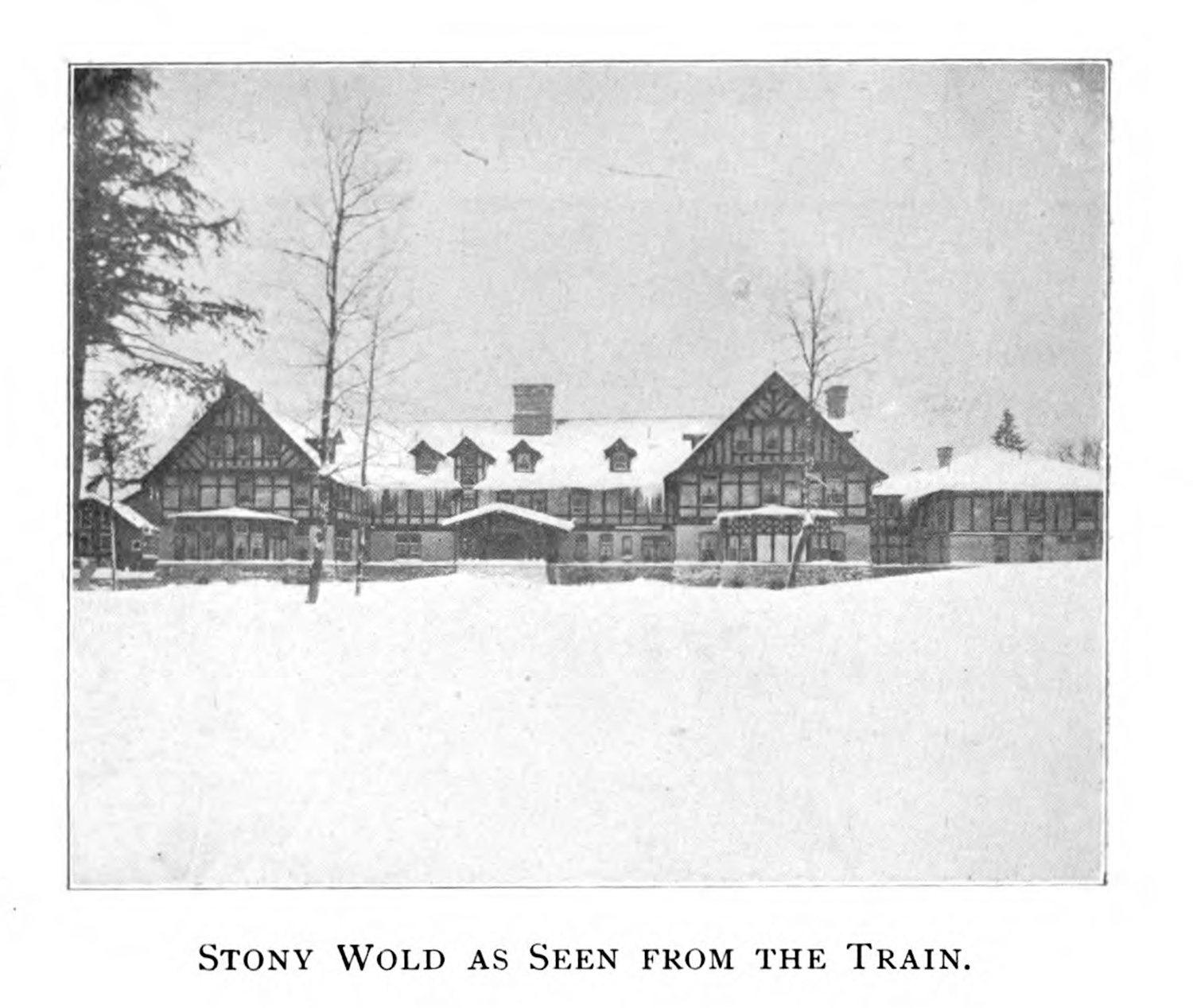

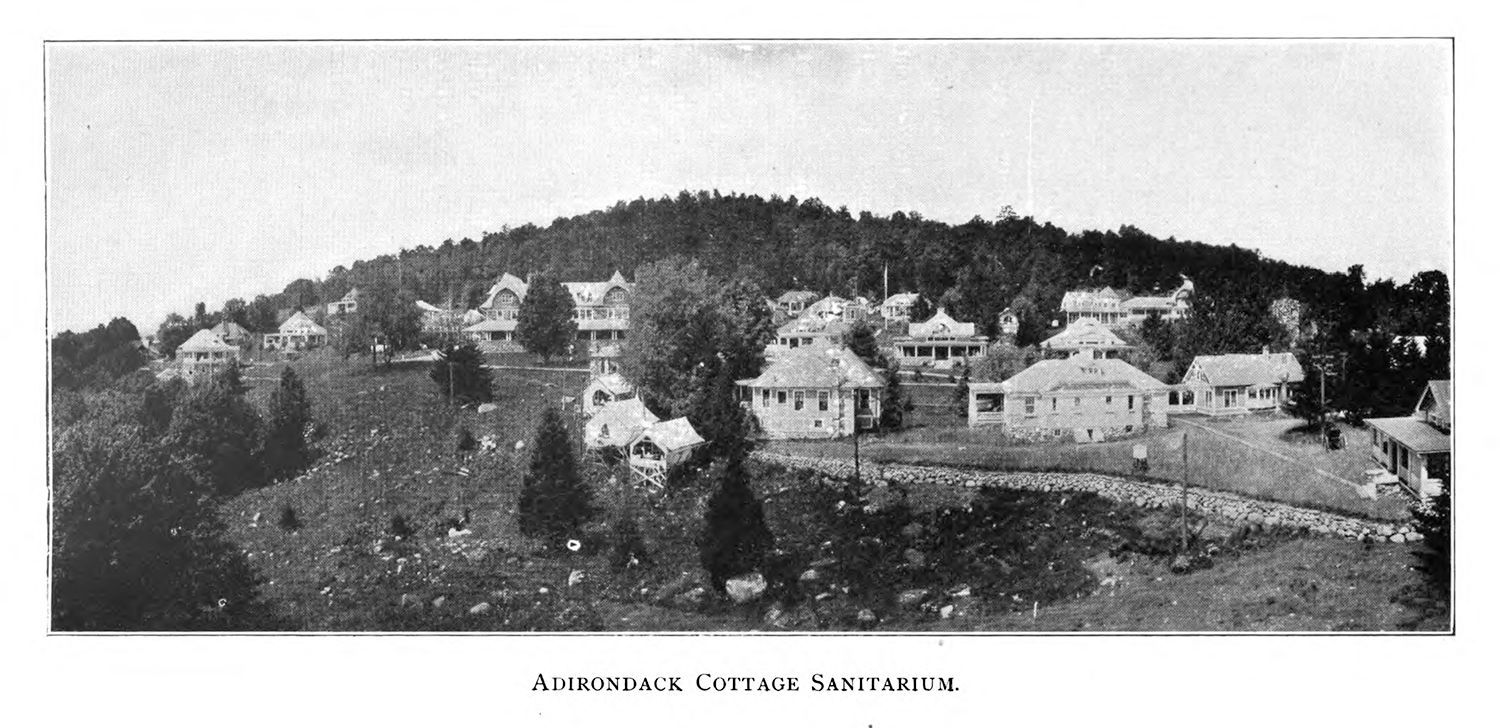

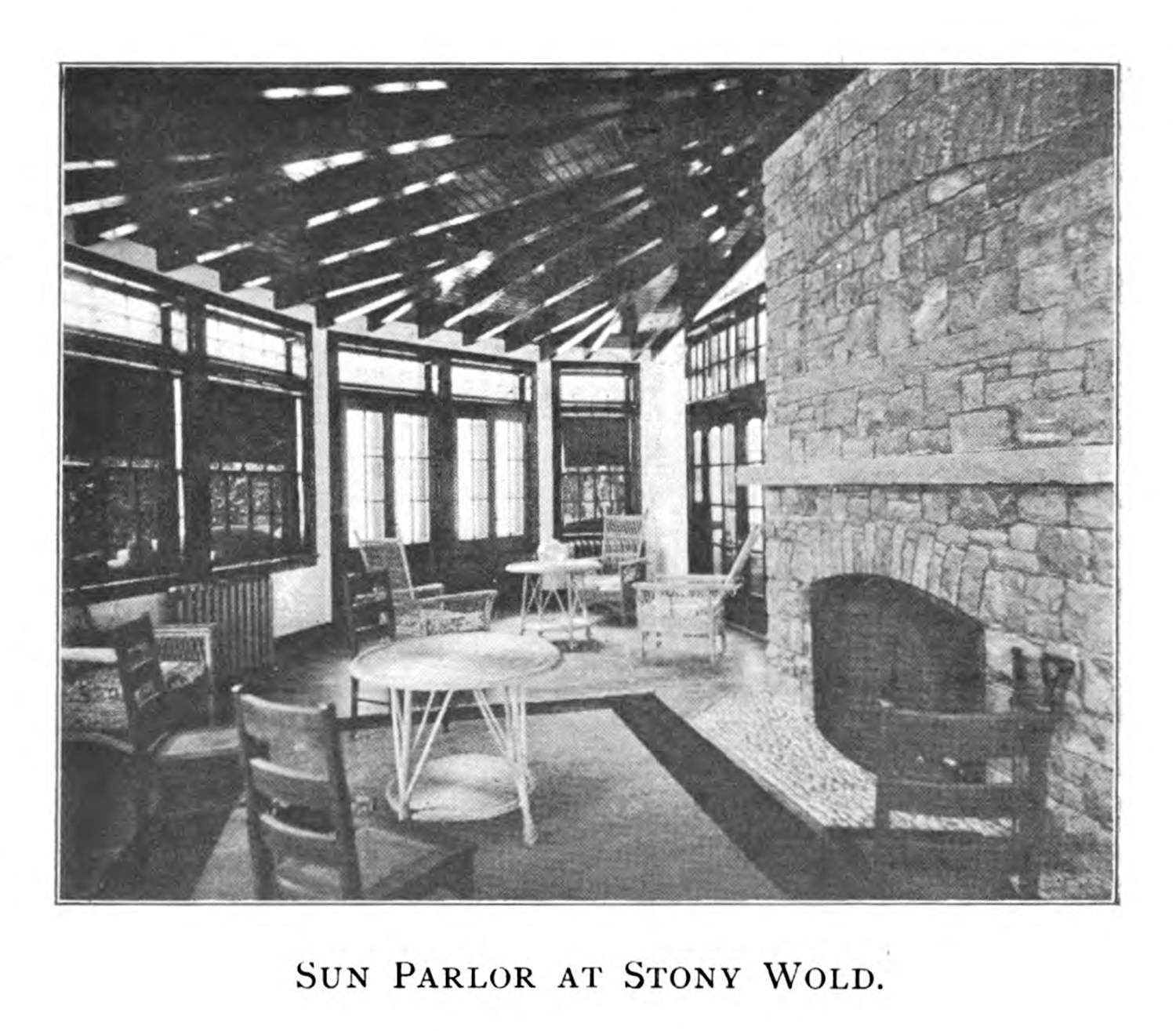

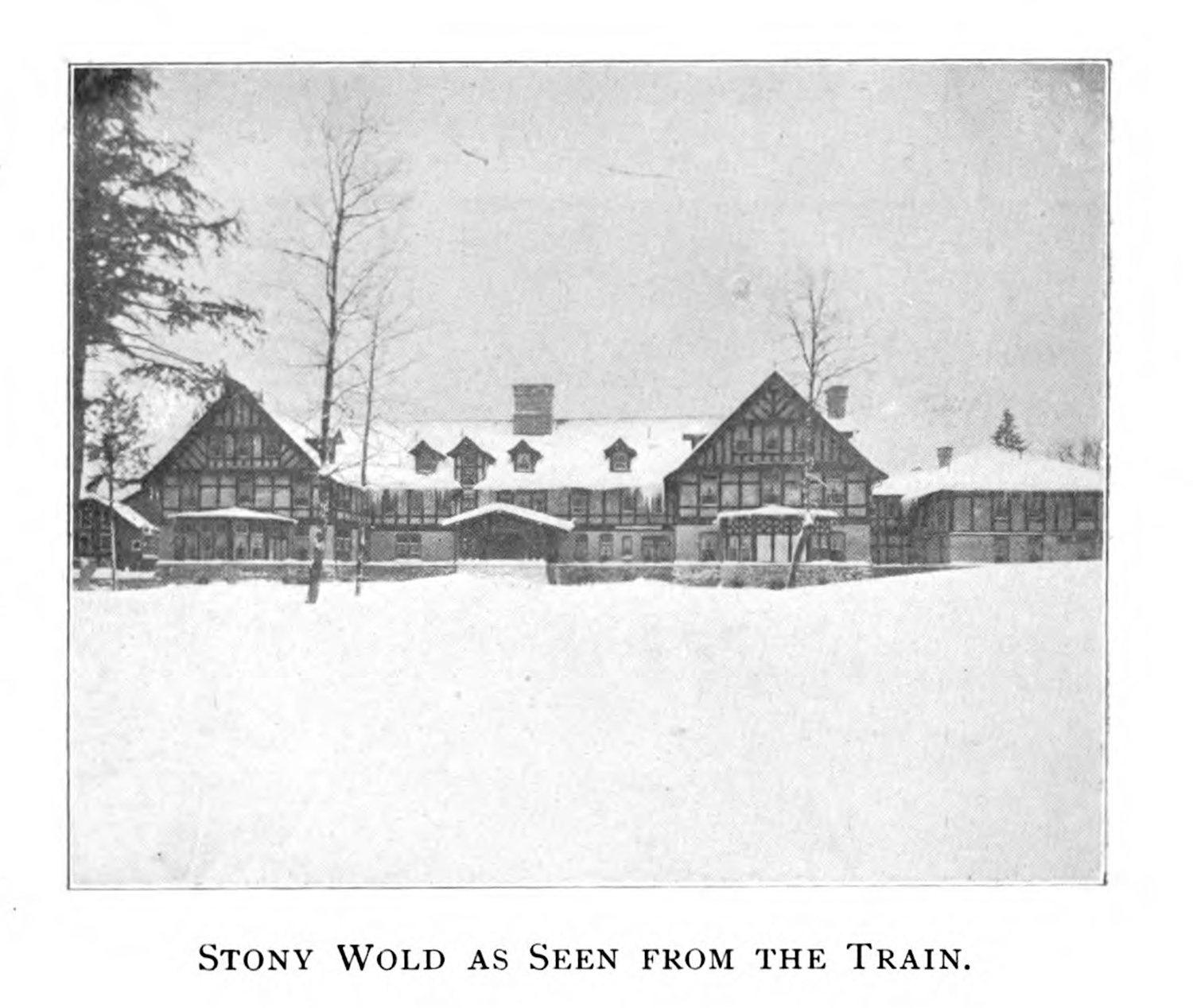

Brandt’s directory, like The British Journal of Tuberculosis, uses photographs to make an argument. There are images of buildings, nestled comfortably in the landscape (figs. 5 & 6), empty and sterile rooms for rest and socialization (figs. 7 & 9), and relatively few images that actually show patients (fig. 8). Curiously, sometimes it looks like patients who are in the frame are left as an afterthought in relation to displaying the luxurious space of the sanatorium (figs. 10 & 11).

Figure 5. An exterior view of a sanatorium, Stony Wood.

Figure 6. An exterior view of the Adirondack Cottage Sanatorium.

Figure 7.

Figure 8. <span class=”opaque-lines>A group of patients as well as a pair of health care workers pose for a picture on the porch of the Muskoka Free Hospital</span>.

Figure 9. On first glance, the veranda at the sanatorium imaged looks empty. On closer inspection, there are a few patients in the background and what looks to be a doctor looking on them from afar.

Figure 11. An empty room save for the presence of a patient’s legs in the foreground.

I use the British Journal of Tuberculosis and Brandt’s directory as examples of a common practice. These images of tuberculosis facilities do not show care they show space. Usually this is inflected with a kind of luxury, adventure, or Romanticism. They sell an image of sickness and of care which responds to what is usually a property investment. Take, for instance, two examples from the American West: the development of the Cragmor Sanatorium and the National Jewish Hospital for Consumptives (NJHC). Both were built from a desire to address a local and national need for tuberculous patient care, but both went about creating their facilities in very different ways.

Built on a bluff overlooking Colorado Springs, the Cragmor Sanatorium was originally meant to be much larger. Brainchild of a well to do doctor [!!!check golden pill book for name], hoping to address the city’s growing sick population, the original sanatorium was meant to be an extravagant health resort for wealthy consumptives, whereby their draw to the city, and their payment for treatment would help fund more charity oriented care. This nineteenth century trickle-down fever dream never realized, and when the Cragmor Sanatorium did open its doors in [!!!year], its facilities and clientele were much less upscale than originally imagined. [!!!Cragmor information from Golden Pill Book]

NJHC was instead developed from a ground-up set of investments from a variety of participants. Prior to the building of their longstanding facilities, the early patients who came to the NJHC were cared for in a series of tents [!!!FindImages?]. After opening its doors in 1899, the hospital continued to expand. They built wards for tuberculous children, expanded their care for adults, and also built facilities for scientific (and specifically bacteriological) research. This was all funded by small donations by the nation’s Jewish population (fig. 12).

TheSanatorium6-10_1916_670

Figure 12. Spivak, Charles, ed. The Sanatorium. 7(1). Denver: 1912, 1.

NJHC and the Cragmor Sanitarium present a capitalistic logic underneath the will to care. I do not mean in the monopolistic or industrial mechanisms of either the gilded age in which they were born, nor the current late-capitalist, privatized medical hellscape; instead, I mean it in the very basic principle of capital, where resources can be leveraged for increased output and gain. I stress this notion of investment, because in many ways these photographs display health as a secondary interest to aesthetics. The photographs that were reproduced for the King Edward VII Sanatorium (figs. 1 & 2) were originally printed in two different contexts: an architectural review and a medical journal. The sanatorium, like a hospital, invested the funds into an infrastructure that could be further leveraged, either toward the care of patients or for the continued profit of the actors who owned it.9 In the case of NJHC, it appears the investments were made in earnest. The capital projects expanded the capacity to treat more patients, and the additional byproducts were leveraged by successive generations, various shifts in leadership, and changes in the nation’s healthcare system.

-

The British Journal of Tuberculosis. (London: Ballière, Tindall & Cox, 1907), 60-61. ↩

-

Ibid., 61. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Vincent Y. Bowditch. “Three Leading Institutions as Seen Through American Eyes — The Newly Completed King’s Sanatorium, in Sussex”, The Journal of Outdoor Life 3(12). 462. ↩

-

Using the bureau of labor statistics inflation calculator (which goes back to 1913), this would equate to around $826/week for care. The number that Bowditch cites as the first proposed cost was eight guineas or, with inflation around $1,319/week for care. ↩

-

For inflation it would be roughly $329. ↩

-

Vincent Y. Bowditch. “Three Leading Institutions as Seen Through American Eyes — The Newly Completed King’s Sanatorium, in Sussex”, The Journal of Outdoor Life 3(12). 461-643. ↩

-

Brandt, Lilian. A Directory of Institutions and Societies Dealing with Tuberculosis in the United States and Canada. (New York, 1904), vii. ↩

-

NJHC still exists, as National Jewish, and the facilities are linked to a robust lung care center in the heart of Denver. While the organization is completely different than that imagined by the National Jewish Consumptive Relief Society, its investments remain. Cragmor, similarly, leveraged both professional and material capital through successive transformations from sanatorium, to nursing program, to an auxillary campus of the University of Colorado system. ↩