Chapter 1

Section 1.0

Section 1.1

Section 1.2

Section 1.3

While I am trying to note trends that I am seeing as I have processed the corpus, and trends that bear out based on the relatively simple calculations I have performed, it should be noted that the representations of the sanatarium in the tuberculous corpus (A.2.0) are relatively diffuse. For public facing publications, the presence [!!!at present] of the architectural figure of the sanatorium alone is not hugely different than its presence in more scientific facing sources (table 1). What is important, for the images in the publicly written material is an interest in multiple subjects imaged at once (with the tag “Group” having 88 correlated entries between it the tag and the “Public Consumption” tag) and an interest in imaging children (with the tag “Child” having 93 correlated entries between it and the “Public Consumption” tag) (table 2).

| Images Based on Correlation Between Tagged Information | |

|---|---|

| Total | |

| Scientific | 1798 |

| Public Consumption | 481 |

| Scientific & Architectural | 817 |

| Scientific & Pathological | 460 |

| Public & Pathological | 71 |

| Public & Architectural | 111 |

| Percentage of Total | |

| Scientific & Pathological | 45% |

| Scientific & Architectural | 26% |

| Public & Pathological | 15% |

| Public & Architectural | 23% |

Table 1. This table shows the total images that are tagged as being from “Scientific” or “Public Consumption” sources, and then shows the number of those images which include the “Architectural” and “Pathological” tags in both. What can be seen is that a similar amount of space is used to show the architectural buildings for publications targeting specific audiences, but that the scientific makes up much more of its total in “Pathological” tagged images. [!!!Revisewhencomplete]

| Public Consumption Total | 481 |

|---|---|

| Public & Group | 88 |

| Public & Group | 18% |

| Public & Child | 93 |

| Public & Child | 19% |

| Public & Child & Sensitive | 11 |

| Public & Child & Sensitive [TOTAL] | 2% |

| Public & Child & Sensitive [Out of the two tags] | 12% |

| Public & Child & Group | 70 |

| Public & Child & Group [TOTAL] | 15% |

| Public & Child & Group (Out of the Two Tags) | 75% |

Table 2. An interesting note here is the outsized presence of children in groups. This is likely due to the group home environments, the discussions of children at open air schools, and so on. [!!!Reviewwhencomplete]

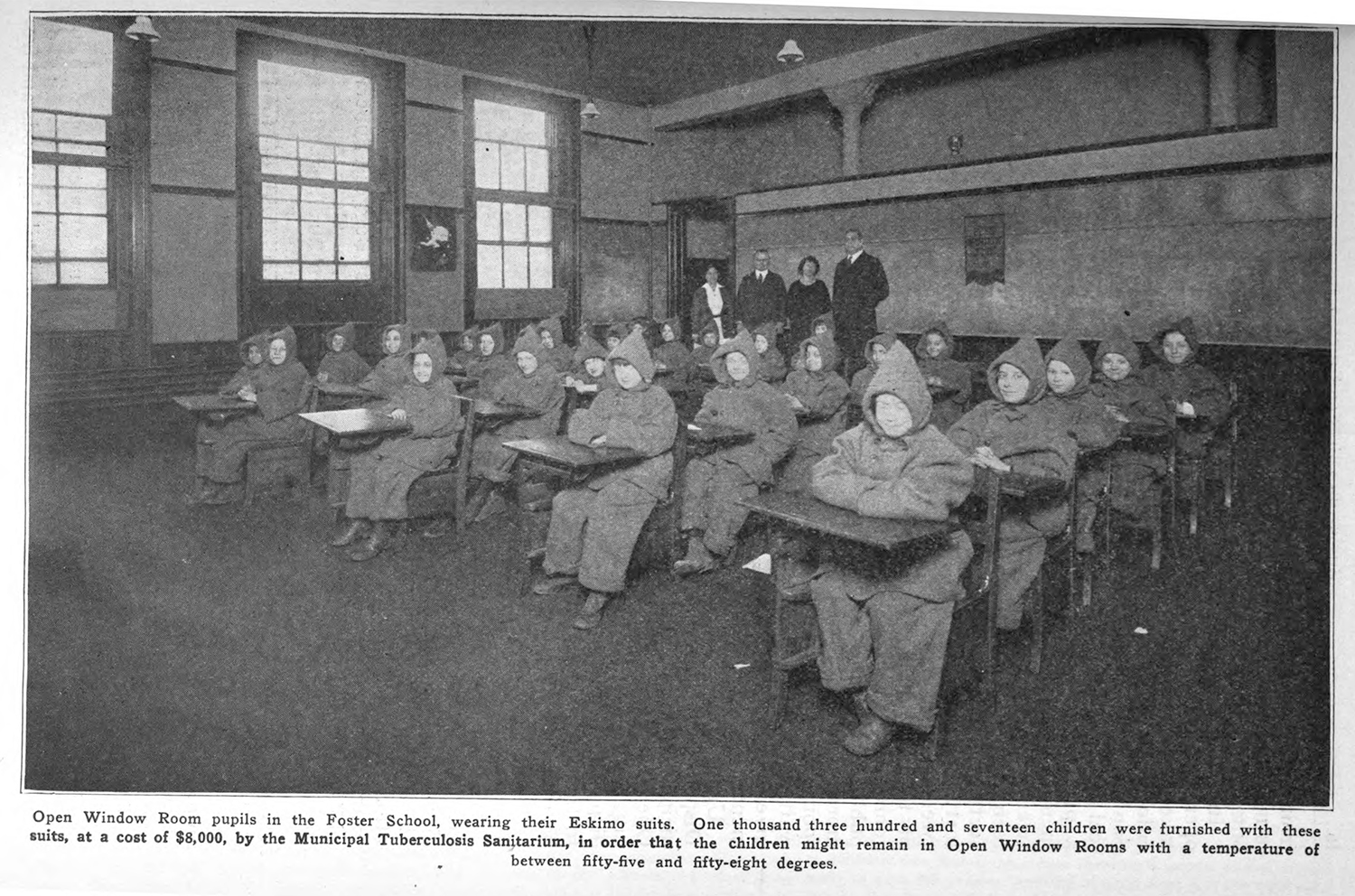

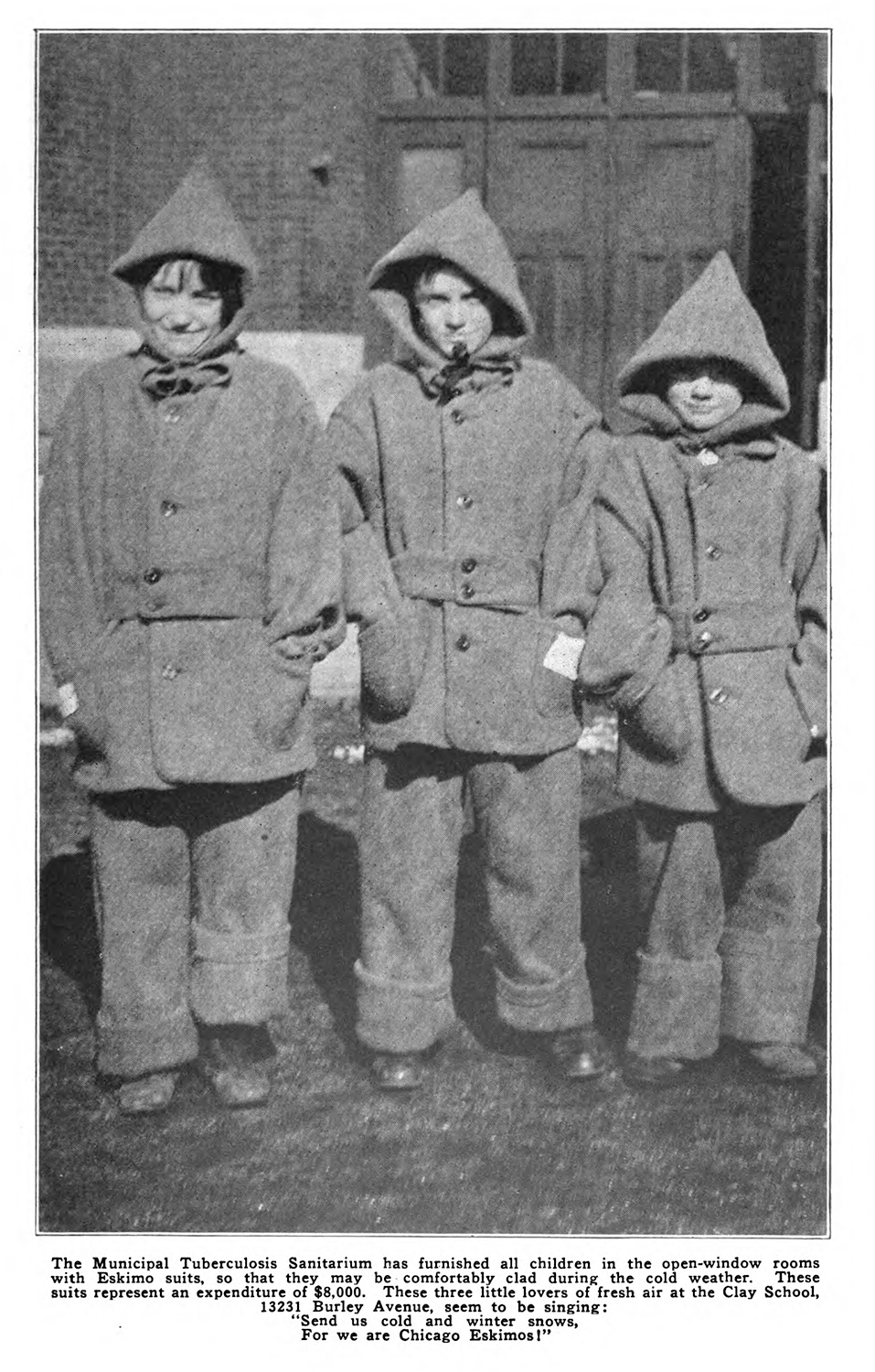

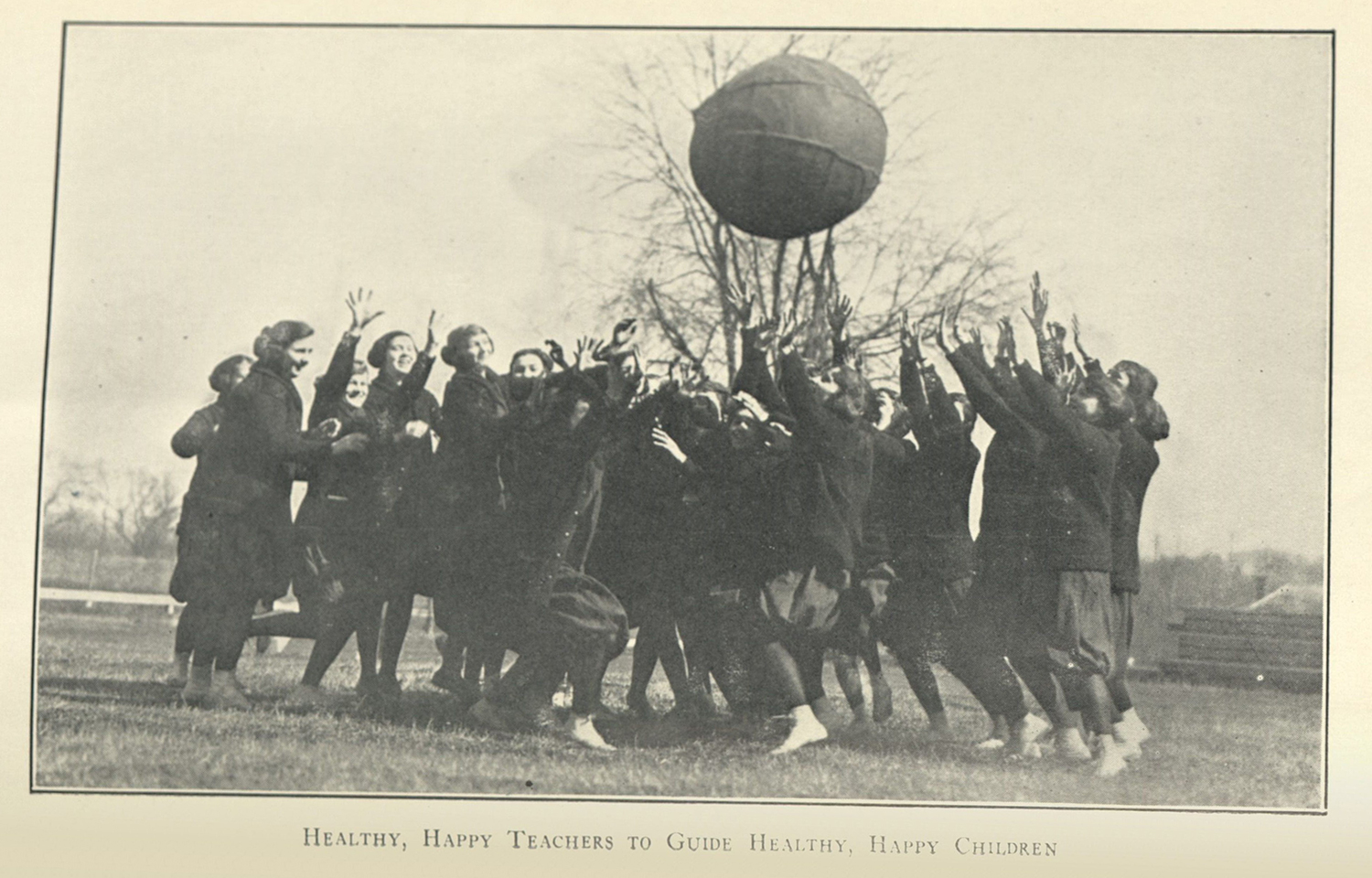

What is left out of the broader sanatoria discussion is an interest in the preventative programs employed by institutions—specifically the open air school (figs. 1 - 2), the day camp for adults as well as children (fig. 3), and the social character of tuberculosis treatment.

Figure 1. Students pose in an open air classroom wearing coats provided to help with the cold.

Figure 2.

Figure 3. A group of teenaged students playing in an outdoor lesson. Courtesy of the New York Academy of Medicine.

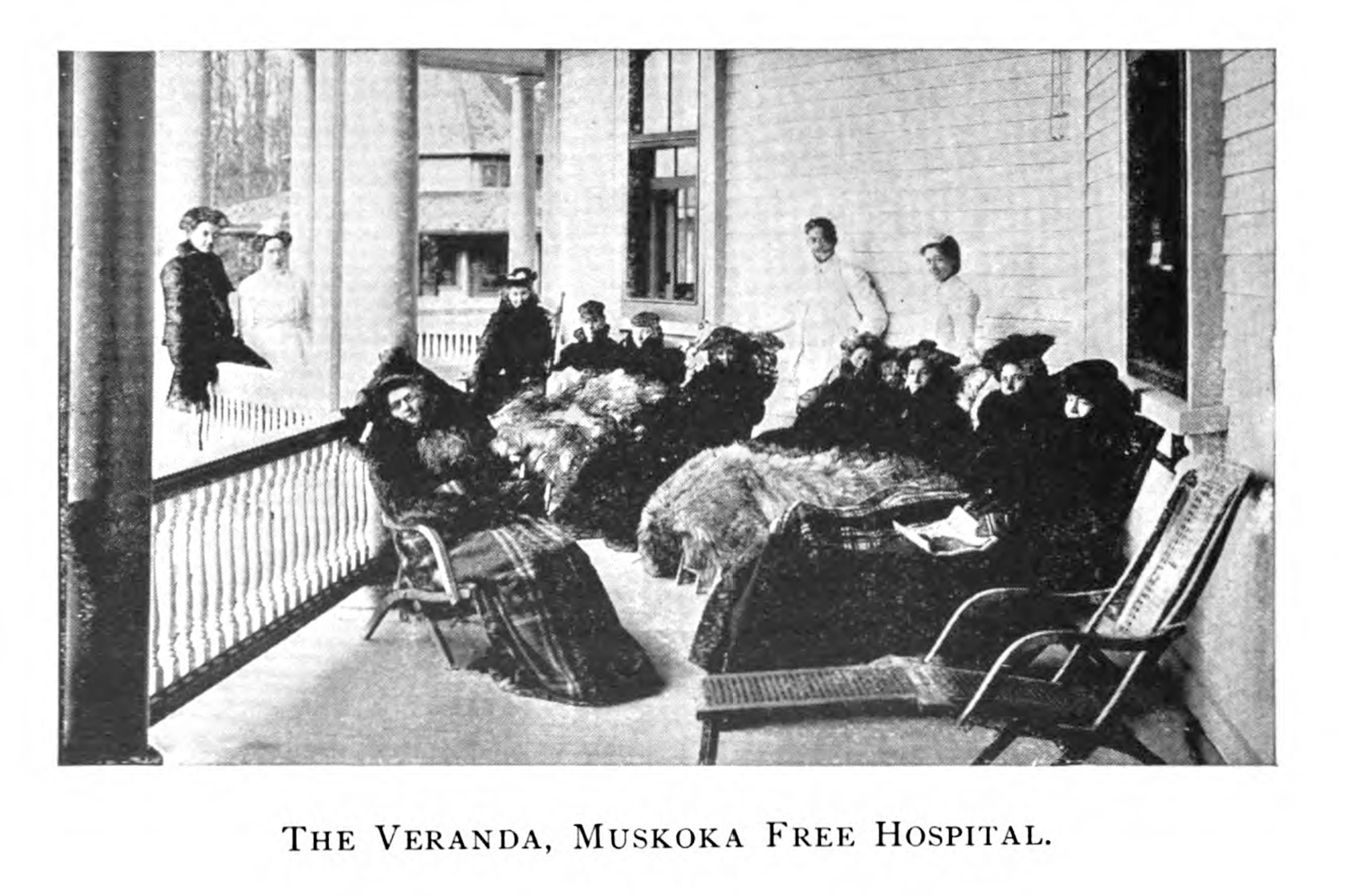

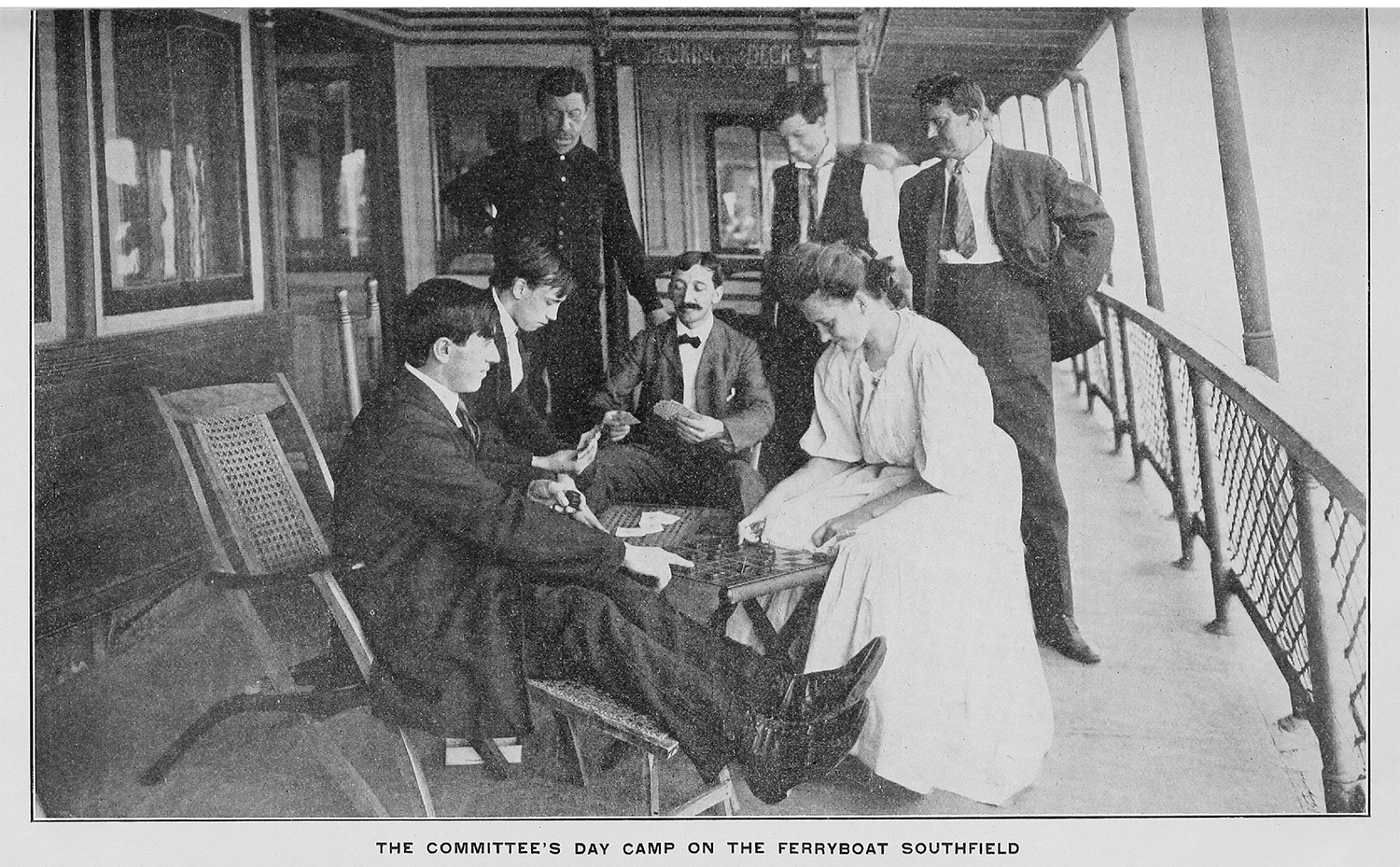

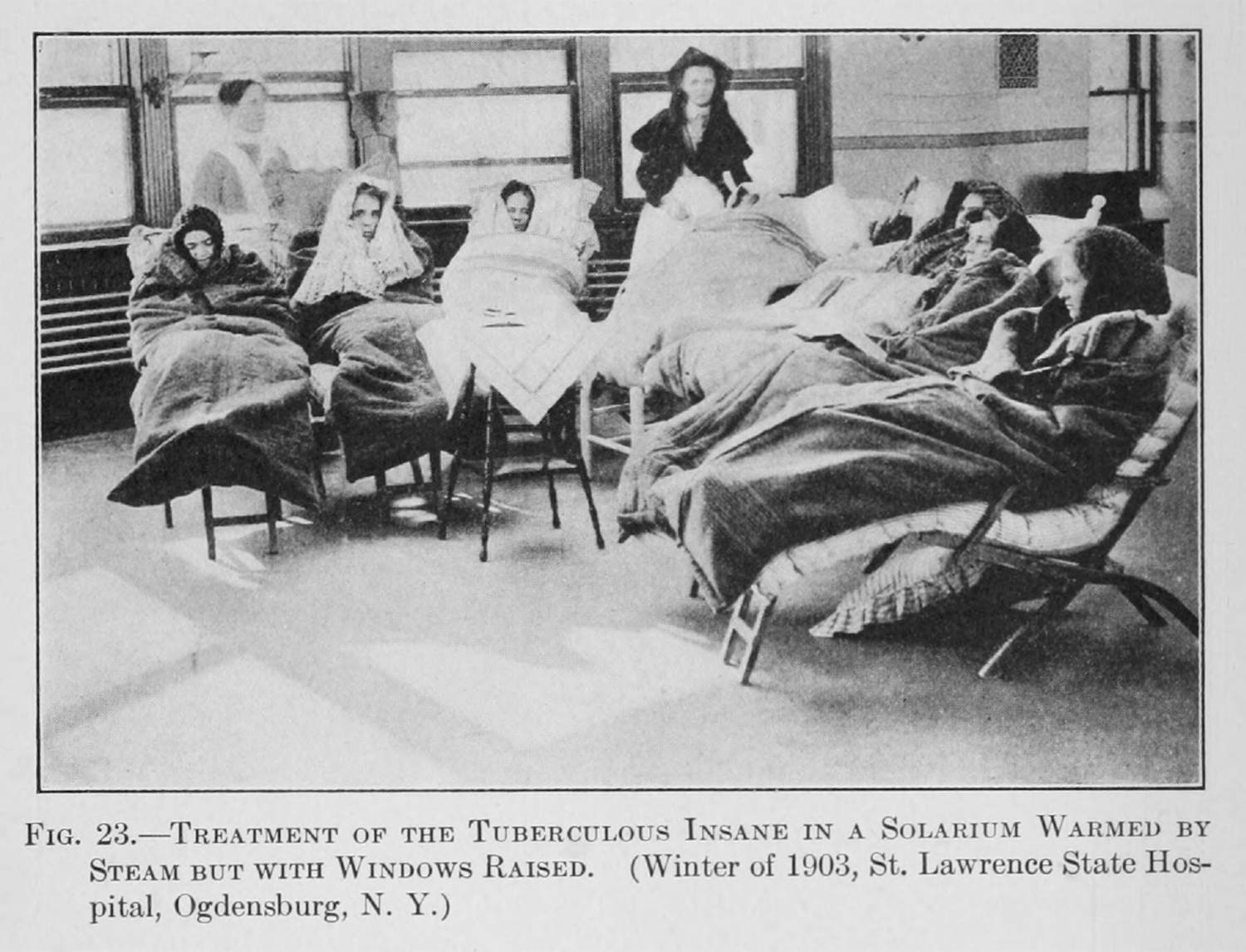

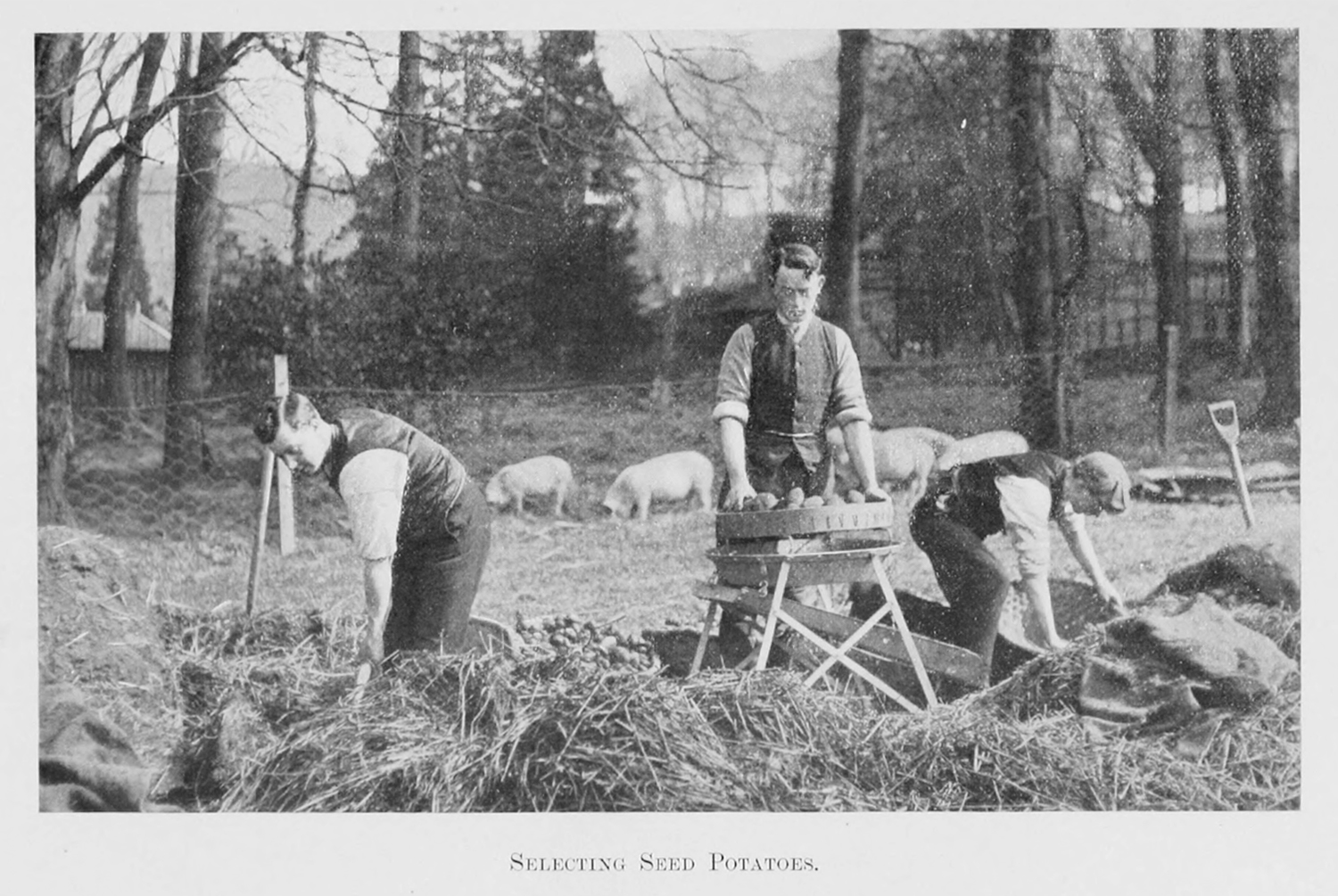

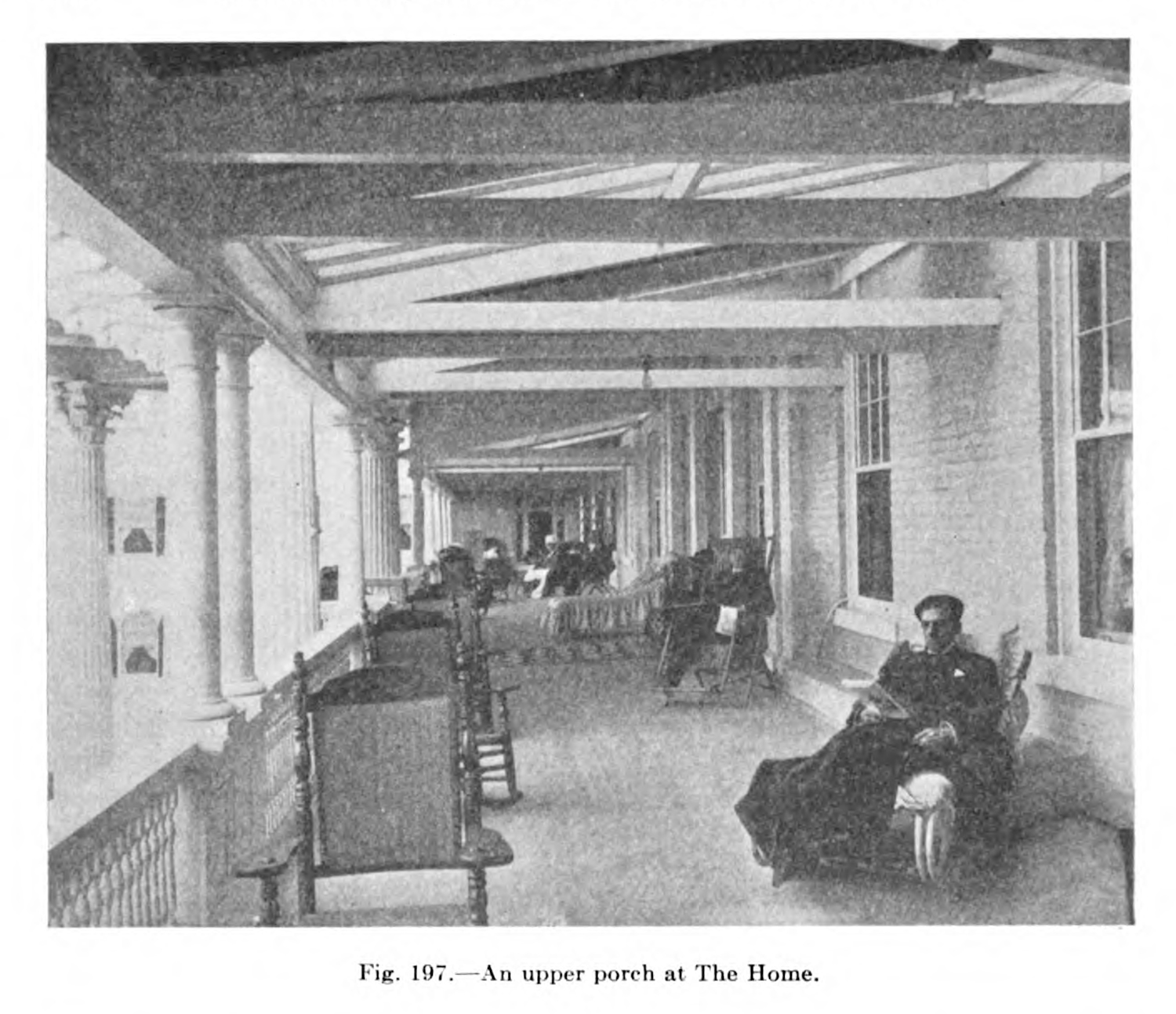

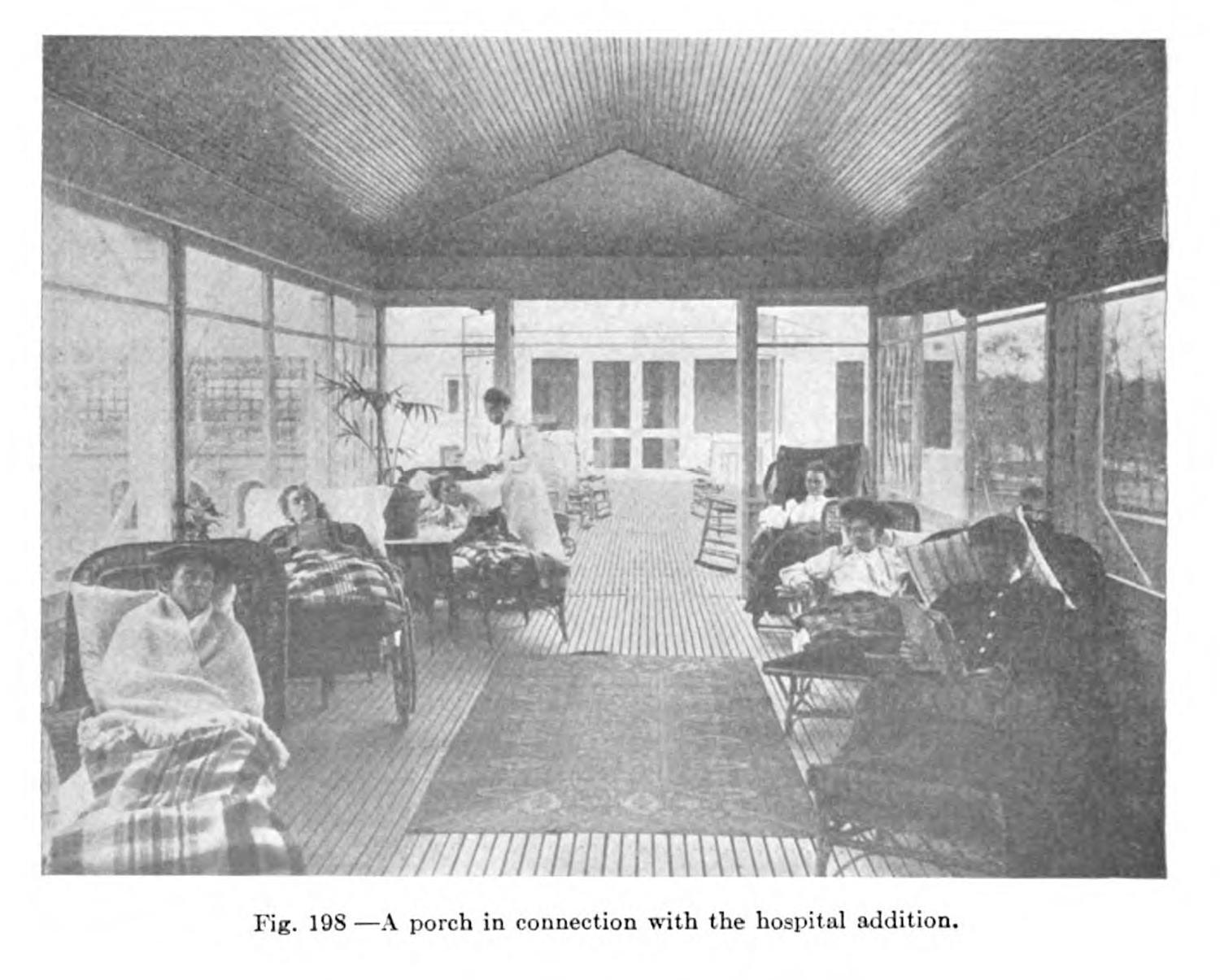

While less common than the architectural image of the sanatorium, there are images which give glimpses (whether intended or otherwise) into a communal life. These images, like those shown in an earlier section (1.2.2) (figs. 6 & 7), represent what life might be like for potential residents. Visions of community, of playing games (fig. 8), of being in a group while taking in air or sunlight (fig. 9), of working together (fig. ), of celebrating together (fig. [!!!FINDAPARTYPIC]), articulate a very different kind of institution from the modern medical no-place (1.2.1). Especially in light of contemporary standards of care, with doctors bustling between patients with little to no time to see them, with egregiously expensive hospital stays, and facilities that have been bled to the fewest staff possible, the transitory space of the current hospital looks unlike the vision imagined for the health-resort-like sanatorium.1 Of course, to make a generalization here, would be an oversight. For example, the Queen Alexandra Sanatorium in Davos sold itself with its private verandas (1.2.3). Moreover (and more perniciously) this construction is at least partly imagined: this is how the institutions who published about themselves imagined themselves.

Figure 6. A group of patients as well as a pair of health care workers pose for a picture on the porch of the Muskoka Free Hospital.

Figure 7. On first glance, the veranda at the sanatorium imaged looks empty. On closer inspection, there are a few patients in the background and what looks to be a doctor looking on them from afar.

Figure 8. A group of adults pose for a picture showing them playing board and card games. [!!!AddCitation]

Figure 9. A group of women sit with heavy sleeping bag like blankets around them. This is an example of some of the precautions taken when patients would be given the open air treatment.

Figure 10. A group of young men work on a farm, selecting seed potatoes. This kind of working cure was more popular in the United Kingdom. [!!!AddCitation]

Figure 11. [!!!A picture from a party] [!!!PLACEHOLDERforPARTY]

When looking at some of these images, I wonder how much of each might be staged, or what may be candid. At the turn of the twentieth century, while photography was being adopted in more uniform ways at some health institutions, it was far from a universally common practice.2 When I read these images, I wonder if in some ways the subjects photographs have been coerced or cajoled or just herded into a proper frame. Even if it is not an entirely constructed thing, as a documentarian (4.1.1), I am hesitant to call anything caught by a camera as true and unconstructed.3 The image of the men working (fig. 11) has a different tenor as one of women sitting in a sunroom (fig. 10), which both have a different kind of relationship to the imaged subject as those who may be caught in the frame or were unwilling to move when a photographer barged into the room (figs. 12 & 13). These latter images show the life at a sanatarium as potentially quite dull and isolating, where the resting verandas, sunrooms, porches and other spaces did not afford the community promised.

Figure 12. A view of an open air resting porch. [!!!AddCitation

Figure 13. A view of an open air resting porch.

Here again, though, I want to move back out, stressing the imagined sanatorium as constructed through the various publications of the corpus. The sanatarium, which serves to solve the health ills of the industrial city (1.2.3), which sold health at a juxtaposition of modern medicine and upper class splendor4 (1.2.2), constructs itself in a kind of anti-flâneur or anti-flâneuse institution. The static subject, whose community is fabricated, but seemingly legitimate, who does not gaze wantingly at the glittering objects they view at the arcade, so much as at the same space.

I cannot attest to whether these images present a true depiction of sanatorium living so much as speculate on why it might have been effective in constructing a metaphor around the disease in the period of interest. In many ways, it seems to promote not just a non-urban image of health, but specifically a higher class one, one which leisure may be enforced, where labor may be displaced on someone’s hourly time, where being to one’s self was not an affront to the wage labor politics of the period. The sanatarium projected a class to which some patients may be able to buy into (if only for a short period) and which insurance may better make possible for a sick patient.5 The issues of class, however, were openly apparent, and the pedagogical model of the sanatarium, hospital, and dispensary created a friction between the learned practices of different classes, and the power and influence of hygienic living.