Introduction

Specimen Studies

0.1.1 | 0.1.2 | 0.1.3 | 0.1.4 | 0.1.5Methods

0.2.1 | 0.2.2The Structure of this Dissertation

0.3.1Tuberculosis' Visual Culture

Visual Practices in Medical Culture

1.1.1 | 1.1.2 | 1.1.3Seeing and Settling in the Sanatorium Movement

1.2.1 | 1.2.2 | 1.2.3 | 1.2.4 | 1.2.5Teaching Public Health

1.3.1 | 1.3.2 | 1.3.3 | 1.3.4 | 1.3.5Representing Doctors in Tuberculous Contexts

1.4.1 | 1.4.2Using Human Specimens in the Study of Tuberculosis

Seeing Disease in Methyl Violet

2.1.1 | 2.1.2 | 2.1.3 | 2.1.4Case Histories

2.2.1 | 2.2.2 | 2.2.3 | 2.2.4Visceral Processes

2.3.1 | 2.3.2Relation

2.4.1 | 2.4.2 | 2.4.3Arts-Based Inquiry

Introduction

3.1.1 | 3.1.2 | 3.1.3 | 3.1.4Terminal Imaginaries & Tuberculous Imaginaries

3.2.1 | 3.2.2 | 3.2.3 | 3.2.4 | 3.2.5 | 3.2.6Dermographic Opacities

3.3.1 | 3.3.2 | 3.3.3 | 3.3.4Tactical Pretensions

3.4.1 | 3.4.2 | 3.4.3Designing Opacity

A Shift towards the Anticolonial

4.1.1 | 4.1.2 | 4.1.3 | 4.1.4Refusals and Opacities

4.2.1 | 4.2.2 | 4.2.3 | 4.2.4Digital and Ethical Workflows

4.3.1 | 4.3.2 | 4.3.3 | 4.3.4 | 4.3.5Conclusion

4.4.1Coda

Prometheus Undone

5.1.1 | 5.1.2 | 5.1.3 | 5.1.4Appendix

The Tuberculosis Corpus

X.1.1 | X.1.2 | X.1.3Web Design

X.2.1 | X.2.2 | X.2.3 | X.2.4Installation Materials

X.3.1 | X.3.2 | X.3.3Index

In 1903, Henry Phipps—a robber baron who made his millions working for the Carnegie Steel Company—opened a research hospital in Philadelphia specializing in care for patients with who could not afford medical care. Having picked Lawrence F. Flick, a well regarded doctor who had previously run the White Haven Sanatorium, the Henry Phipps Institute sought to care for the city’s consumptive patients, offering free care, a dispensary, and additional aid. A charity institution and research hospital, it also studied the patients under its care.

As part of this project, the doctors at the Henry Phipps Institute took detailed notes about their patients, and when a patient died in their care, their body was autopsied. In the institute’s second annual report, Flick made a nonchalant comment about their growing medical museum:

Long before the end of the first year the Institute had reached the full capacity of its quarters and had used every available foot of floor space for some useful purpose. The building had gradually shaped itself along lines of utility until every part of it had been used for that purpose to which it was best adapted and for which it could be used with least friction and inconvenience. The nurses had already been crowded out of the building and the space which had been set aside for laboratory work and for a pathological museum was rapidly growing inadequate.1

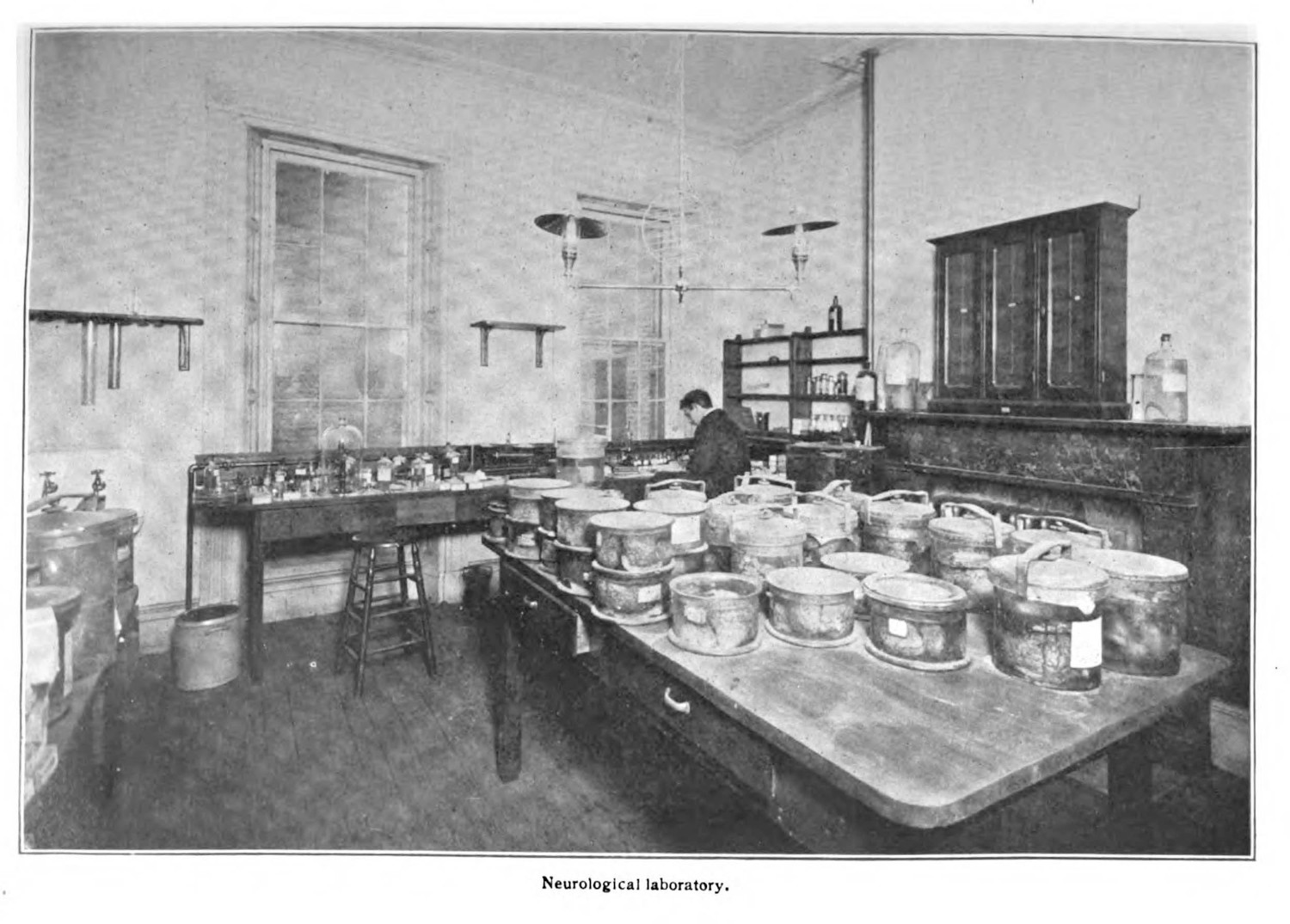

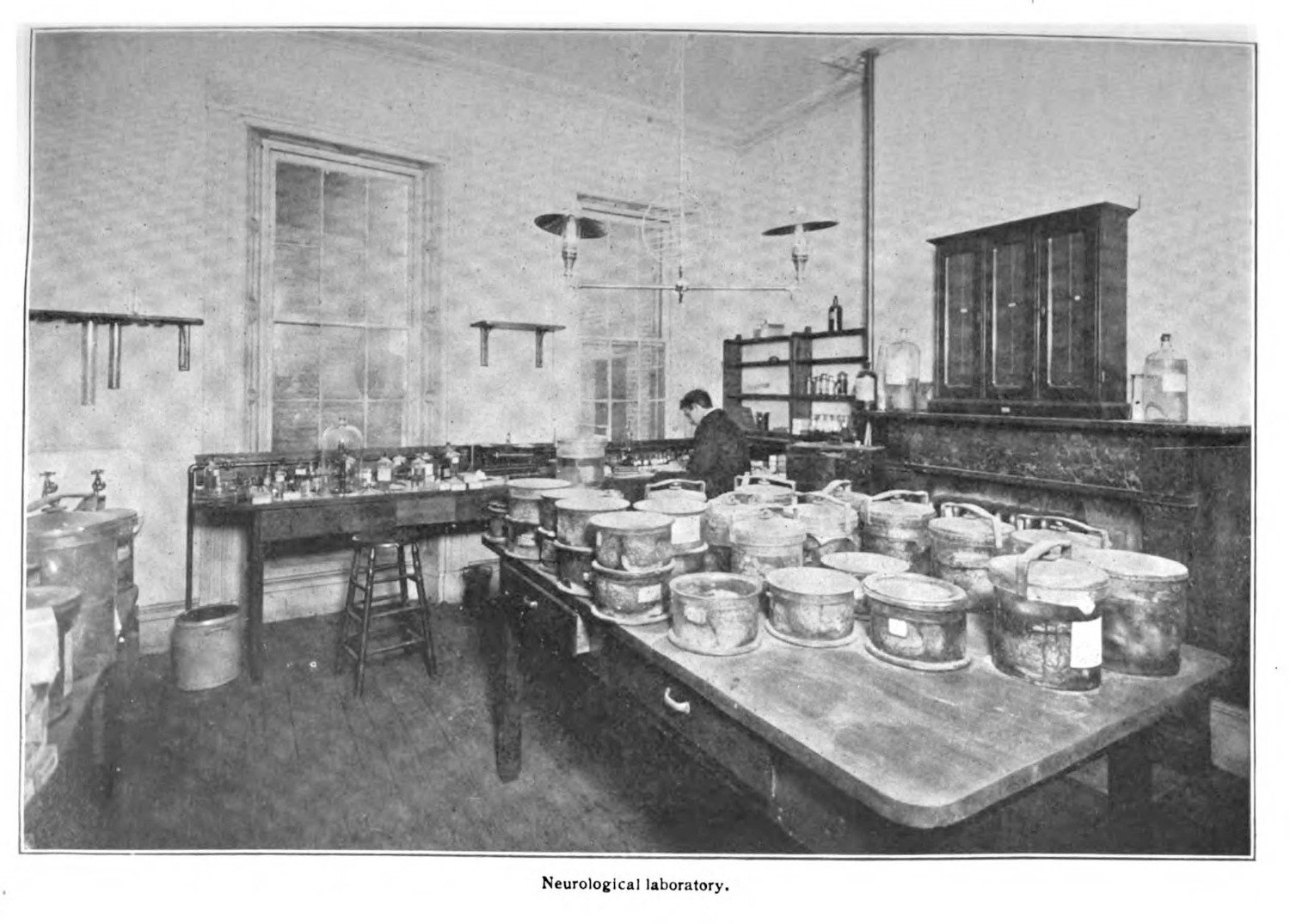

When Flick writes of the institute’s pathological museum, he is referencing to the institute’s collection of wet specimens—human biological material preserved in fluid, like formalin or an alcoholic spirit—all of which had been taken from patients at autopsy (fig. 1). The overflowing collections were the result of an influx of human material taken from dead patients, which promised to be of some use for scientific research.

Operating on a new model of philanthropy established by John D. Rockefeller’s medical research institute, the Phipps Institute both sought to cure patients with tuberculosis, while also using them for research. As Barbara Bates tells it, Flick’s ambitious plan saw the linkage of patient care and medical research as necessary to the disease’s eventual conquest. She writes, “Out of [the Institute’s] dispensary and hospital would come the materials for the scientific laboratory, and from the knowledge accumulated in all three places there would develop some new answers to the old disease.”2 While teaching hospitals had often used their patients as material for research and education,3 the Phipps Institute targeted tuberculosis specifically, seeing every patient that entered its doors as a potential research object that might be useful in the growing war against the chronic bacterial infection (0.1.4; 2.3.1). The doctors of the Phipps Institute treated hundreds of patients, with 150 people dying in the first two years of operation. Of those who died 143 were autopsied, and their remains, taken piecemeal as necessary, quickly overfilled the museum.

The Henry Phipps Institute’s specimen collection was not an outlier, but the commonly held best practice for doing medical research. Anatomical and pathological museums had, for a century, been a central part of medical education. In the nineteenth century, the best medical schools were determined because of their extensive or famous collections.4 These materials were often accumulated through theft, and they were the backbone of a myriad of entwined disciplines, with medicine and anthropology being the most egregious practitioners. More often than not, especially in the United States, the human remains used for biomedical collections were stolen from communities of difference, with Black and Indigenous remains being most commonly subjected to post-mortem abuse.5

The Henry Phipps Institute, and the medical community broadly at the turn of the twentieth century, represents the problem that this dissertation addresses: the body of a sick, dying, or dead patient was epistemically valuable (0.1.3). The patient’s body was a resource,6 something that held secrets in the war against tuberculosis (2.3.1), if only doctors could examine in full enough detail in life and after death (4.1.1). Medical science depends on the patient for its claims, and this dissertation articulates the way this dependence benefits biomedical actors while actively harming research subjects.

To do this, I examine the specimen—a representational, media object. The specimen mediates natural occurrences in the body of a patient through various methods—wet tissue specimens (2.2.1), clinical photographs (2.2.2), microscopic illustrations (2.1.1; 2.1.3), x-rays, case studies (2.2.3), and recorded biometrics—framing, preserving, and defining a pathological or anatomical phenomenon through the application of different technologies of preservation and reproduction. The specimen purports to represent a phenomenon—the effects of pulmonary tuberculosis in a lung, the profusion of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in a sputum sample (2.1.3), the outcomes of a surgical intervention on a patient—but requires various technological and material interventions to make them legible to a scientific audience (0.1.4; 2.3.1). These objects are almost exclusively taken from the bodies of patients, and this practice of scientific capture both anonymizes and naturalizes the phenomena on display (0.1.4).

This dissertation looks to tuberculosis—a chronic infection that was linked to Mycobacterium tuberculosis in 1882 (2.1.1)—as a case study to examine the ways specimens were used in biomedical argument. I look at tuberculosis because of its stickiness both as a malady and cultural obsession (1.1.1), and I look to the period following its microbial discovery by Robert Koch (2.1.1; 2.1.2; 2.1.3) because this same period saw the rise of American medicine internationally, and because Koch’s microbial arguments led to an explosion of public and private approaches to caring for patients with tuberculosis (1.2.3; 1.2.4). Looking at a prominent disease in this period of medical expansion and professionalization enables me to link these ideological processes to medicine’s epistemic reliance on specimens (0.1.2).

-

Report of the Henry Phipps Institute for the Study, Treatment, and Prevention of Tuberculosis. Vol. 2. Philadelphia: Henry Phipps Institute, 1906. 4. ↩

-

Bates, Barbara. Bargaining for Life: A Social History of Tuberculosis, 1876-1938. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1992. 98. ↩

-

Hutton, Fiona. The Study of Anatomy in Britain, 1700-1900. London: Routledge, 2013; Richardson, Ruth. Death, Dissection and the Destitute. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1987. ↩

-

Alberti, Samuel J. M. M. Morbid Curiosities: Medical Museums in Nineteenth-Century Britain. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011. ↩

-

Blakely, Robert L., and Judith M. Harrington, eds. Bones in the Basement: Postmortem Racism in Nineteenth-Century Medical Training. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1997; Redman, Samuel J. Bone Rooms: From Scientific Racism to Human Prehistory in Museums. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2016; Sappol, Michael. A Traffic of Dead Bodies: Anatomy and Embodied Social Identity in Nineteenth-Century America. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2002. ↩

-

Liboiron, Max. Pollution Is Colonialism. Durham & London: Duke University Press, 2021. ↩