Introduction

Specimen Studies

0.1.1 | 0.1.2 | 0.1.3 | 0.1.4 | 0.1.5Methods

0.2.1 | 0.2.2The Structure of this Dissertation

0.3.1Tuberculosis' Visual Culture

Visual Practices in Medical Culture

1.1.1 | 1.1.2 | 1.1.3Seeing and Settling in the Sanatorium Movement

1.2.1 | 1.2.2 | 1.2.3 | 1.2.4 | 1.2.5Teaching Public Health

1.3.1 | 1.3.2 | 1.3.3 | 1.3.4 | 1.3.5Representing Doctors in Tuberculous Contexts

1.4.1 | 1.4.2Using Human Specimens in the Study of Tuberculosis

Seeing Disease in Methyl Violet

2.1.1 | 2.1.2 | 2.1.3 | 2.1.4Case Histories

2.2.1 | 2.2.2 | 2.2.3 | 2.2.4Visceral Processes

2.3.1 | 2.3.2Relation

2.4.1 | 2.4.2 | 2.4.3Arts-Based Inquiry

Introduction

3.1.1 | 3.1.2 | 3.1.3 | 3.1.4Terminal Imaginaries & Tuberculous Imaginaries

3.2.1 | 3.2.2 | 3.2.3 | 3.2.4 | 3.2.5 | 3.2.6Dermographic Opacities

3.3.1 | 3.3.2 | 3.3.3 | 3.3.4Tactical Pretensions

3.4.1 | 3.4.2 | 3.4.3Designing Opacity

A Shift towards the Anticolonial

4.1.1 | 4.1.2 | 4.1.3 | 4.1.4Refusals and Opacities

4.2.1 | 4.2.2 | 4.2.3 | 4.2.4Digital and Ethical Workflows

4.3.1 | 4.3.2 | 4.3.3 | 4.3.4 | 4.3.5Conclusion

4.4.1Coda

Prometheus Undone

5.1.1 | 5.1.2 | 5.1.3 | 5.1.4Appendix

The Tuberculosis Corpus

X.1.1 | X.1.2 | X.1.3Web Design

X.2.1 | X.2.2 | X.2.3 | X.2.4Installation Materials

X.3.1 | X.3.2 | X.3.3Index

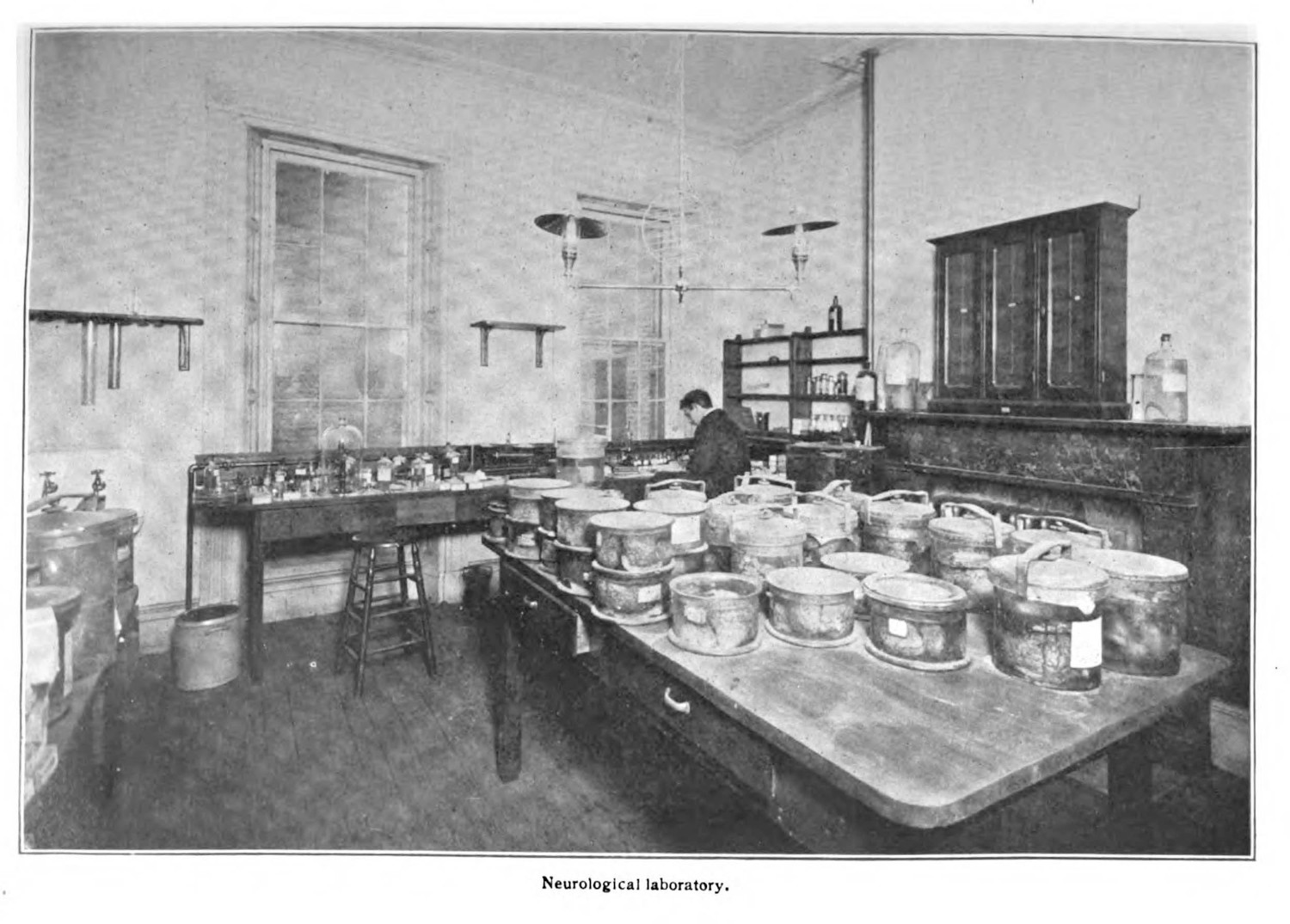

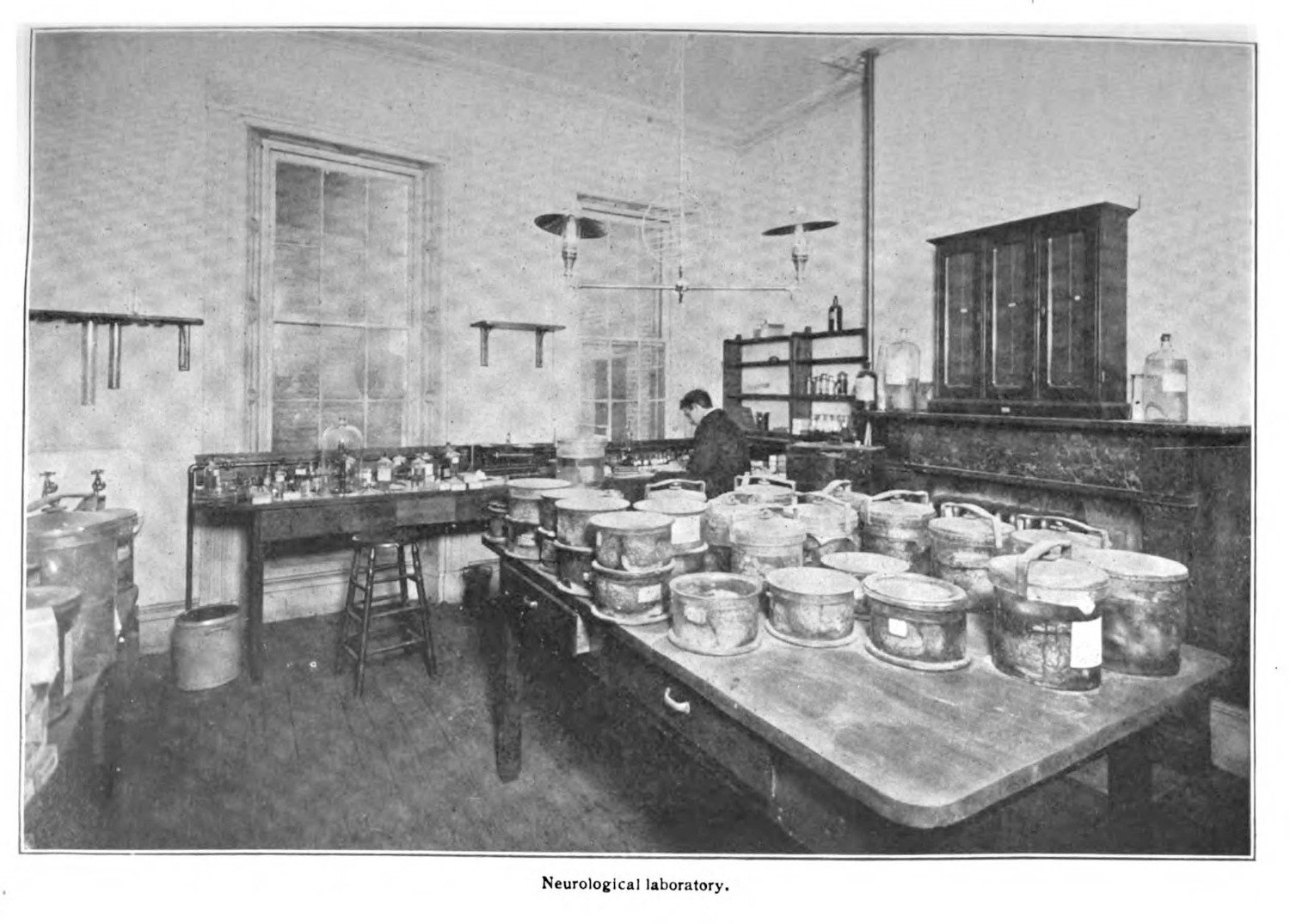

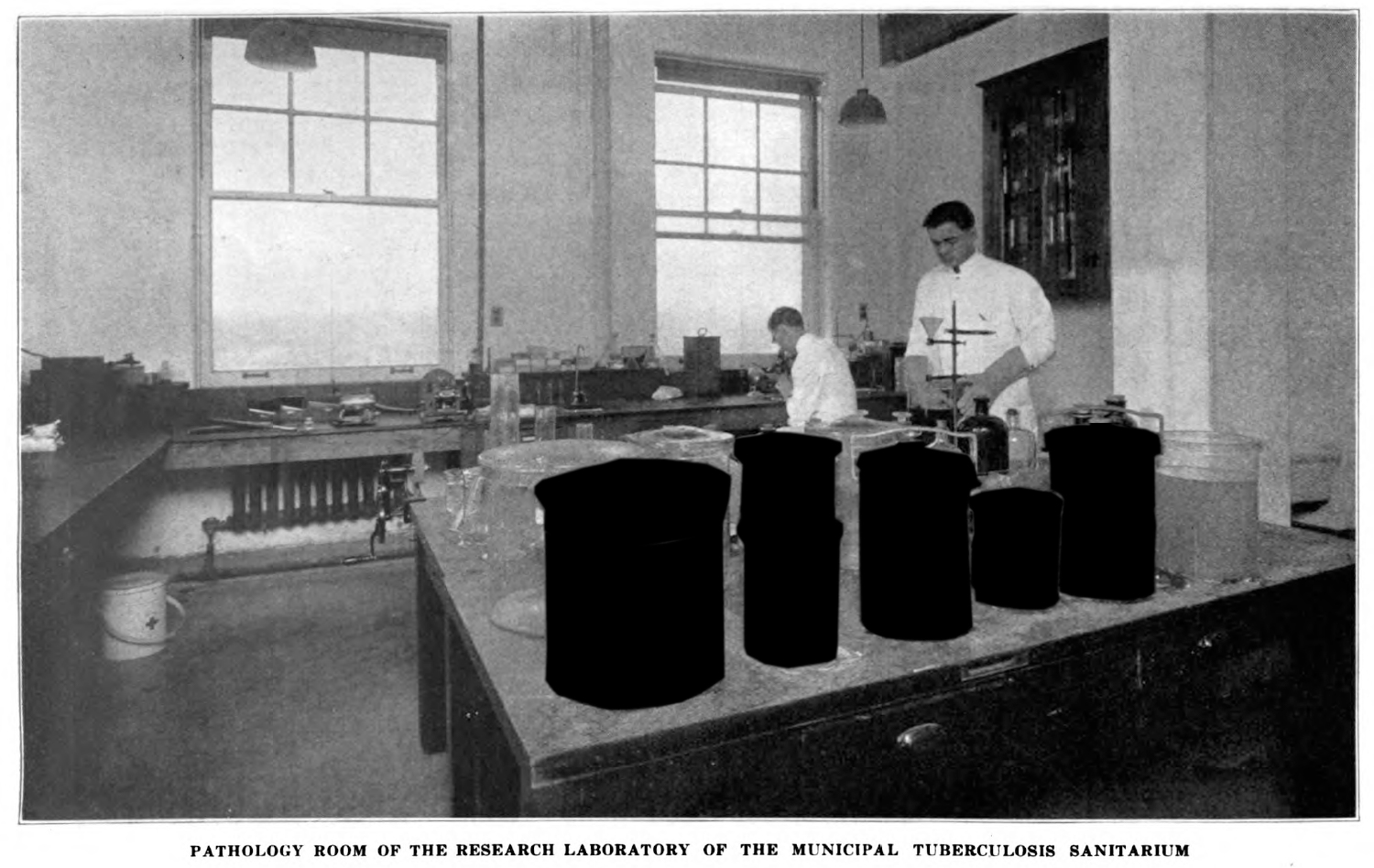

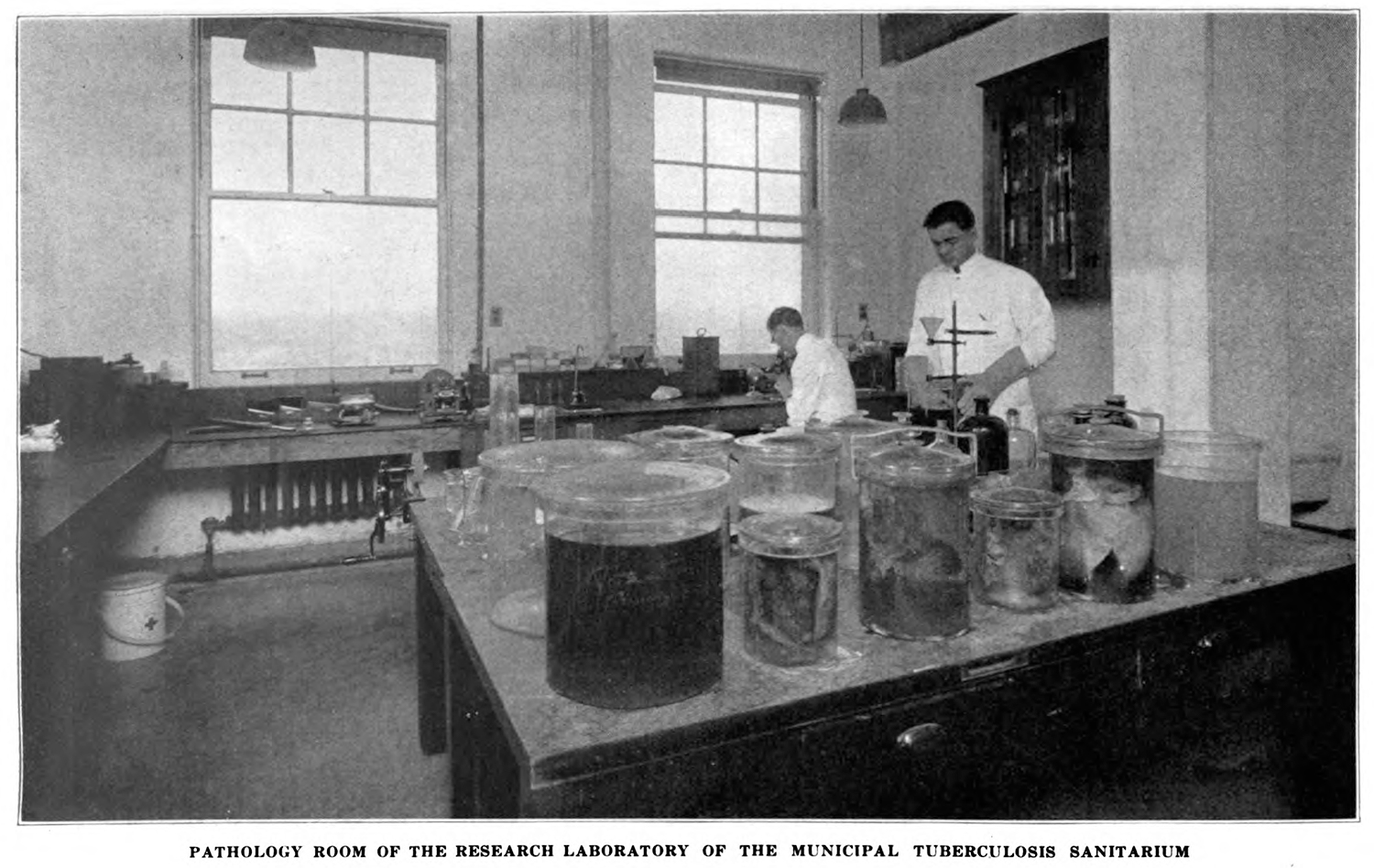

In the introduction to this dissertation, I mentioned how the pathological museum at the Henry Phipps Institute quickly outgrew the space that had originally been designated for specimen storage. The photograph that accompanied this history displayed a collection of brains in the foreground, and the medical scientists who worked in this space in the background (fig. 1) (0.1.1). While not hugely common, photographers sometimes caught doctors in their labs, with human remains on display in the mise en scene (fig. 2) (1.4.1).1

For the Henry Phipps Institute photograph (fig. 1), the materials were certainly acquired through posthumous examination: the wet specimens on display were brains. They were collected under the assumption that they might be valuable for research, with specific interest in understanding the fast-moving meningeal tuberculosis, which affected the brain. Also known as galloping tuberculosis, a patient with this rarer form of the disease would have weeks, rather than months or years before succumbing to the infection (2.2.3).

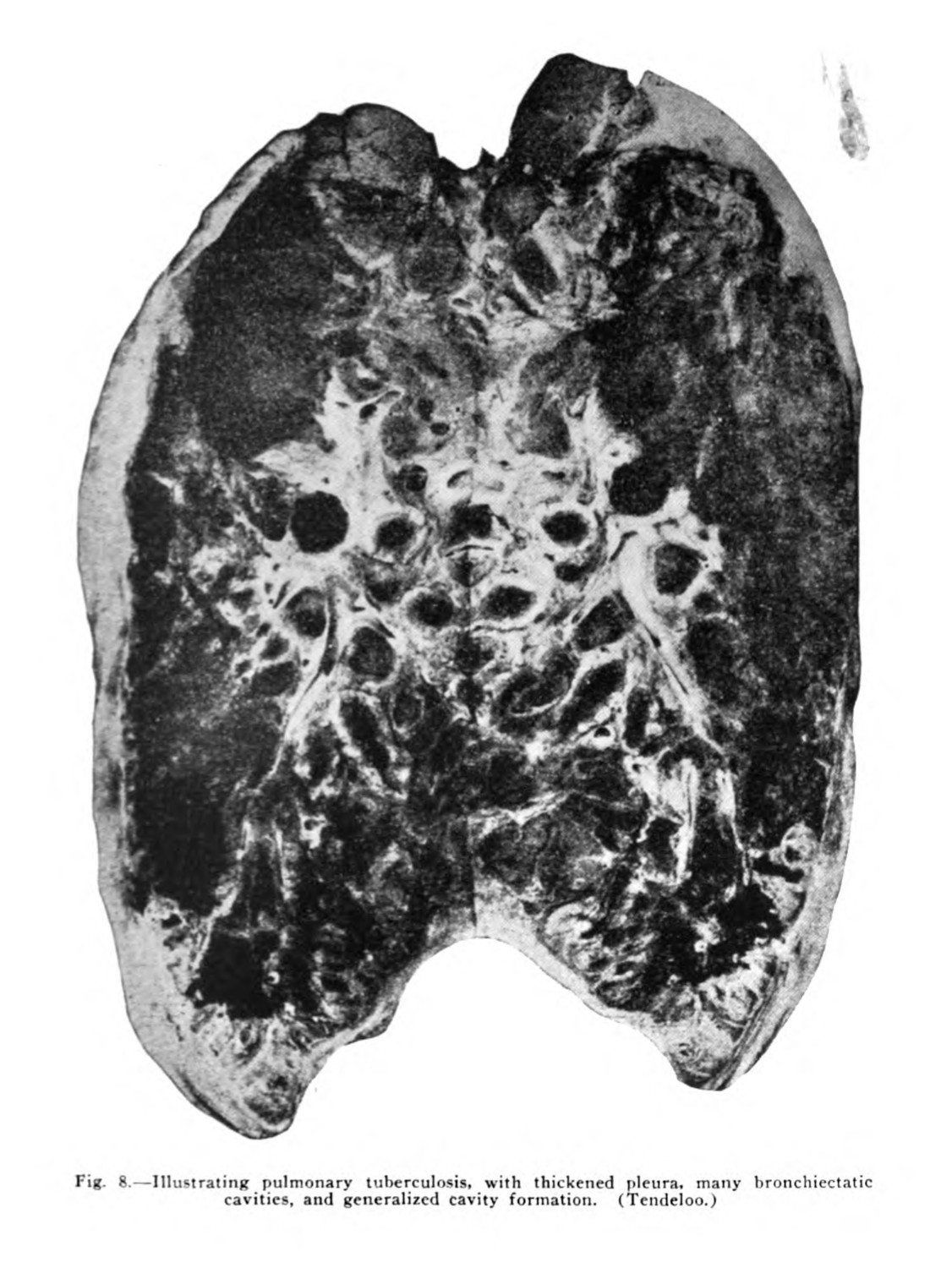

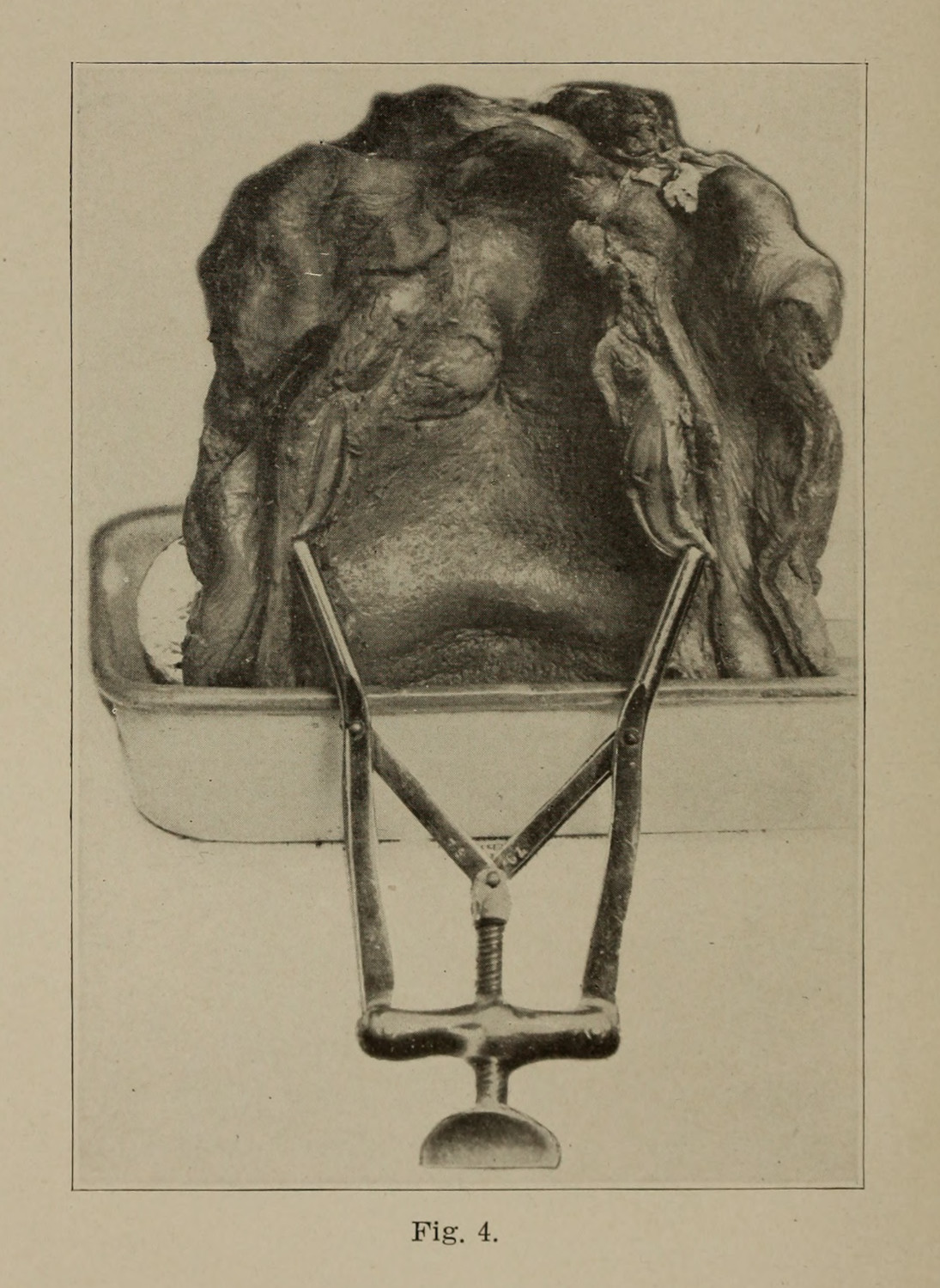

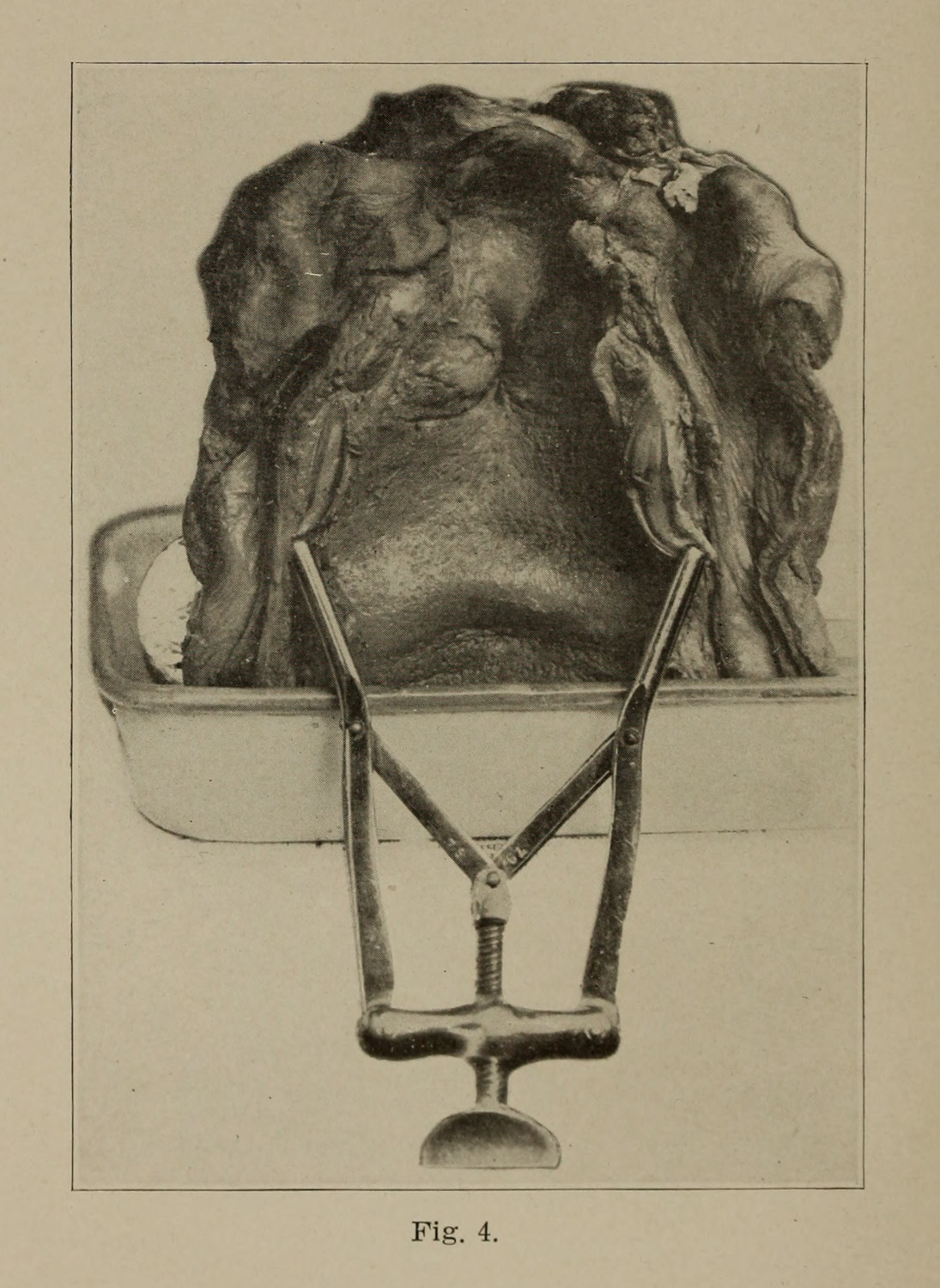

The human material preserved in these jars were useful for many reasons, as they could be removed for close inspection and microscopic study.2 My interest is in seeing wet tissue specimens as a visual medium. As they are displayed in medical museums like Philadelphia’s Mütter Museum or Surgeons Hall in Edinburgh, spectators are distanced from these materials, a viewer may only engage with the specimen from a distance, gazing through the jar to see the organ, its image bent by the shape of its container and the formalin solution. This is the same relationship that viewers have with photographs of wet specimens: there is a certain distance and separation between viewer and object (figs. 3 & 4).

As I move to analyze human specimens what I want to think about is how their materiality and their object history is necessary for the production of medical knowledge. Just as Koch’s method depends on a careful isolation of bacteria, incubated originally in the body of a symptomatic animal (2.1.2; 2.1.4), there too is a necessary linkage between sick subject and research object.

This thinking comes out of a nest of discourses around new materialism and artifact life histories. New materialism embraced the posthuman turn to examine how objects, animals, and technologies interact without or in parallel to human culture,3 and it has been used in a variety of conversations around media studies, from ecological perspectives to media technology to the preservation of significant historical materials (2.4.2).4 Life histories, which Igor Kopytoff first described, considers the extended life of cultural artefacts, beyond the realm of their original construction and consumption.5 This framework helps imagine and describe the connectivity between human subject and the specimen that is produced from their body. For my examination of the wet tissue specimen, it is important to maintain the continuity between dying subject and research object, even if that shift in terms tries its best to displace those two nested forms: from a body to an organ.

The reason for this move is to displace the process of clinical vision in the context of biomedical research. Just as Koch’s vision is mediated by a series of processes—material, embodied, chemical, cultural—so too are the visuals produced for scientific study and reflection. I am turning away from the constructedness of vision writ large (1.1.2) to think more about how the specimen itself is a constructed research object. There is still a visual character, but my shift is to focus on a continuity between a human patient and the various transformations—material, conceptual, chemical, contextual—that occur in the creation of a specimen.

While many of the images that I look at in this section are photographs, the production of those images depends on different technological and methodological practices. These practices, like Koch’s methods in the previous section (2.1.2; 2.1.3), work to make the phenomenon visible to the intended audience, but in this process they discipline the material. Discussing the ways the cinema was articulated for the purposes of human motion study by Wilhelm Braune and Otto Fischer, Scott Curtis describes the double-sided process of disciplining the subject and the capture apparatus:

At each stage of Braune and Fischer’s experiment, they had to make adjustments to the subject, the apparatus, and the means of analysis. The recruit’s body, for example, had to be continually manipulated and adjusted to create a legible image. Indeed, just as adapting the subject’s body to the apparatus, and vice versa, played a large role in creating and legitimating a scientific image, so adapting labor to the machine age was the primary goal of the science of work. Likewise, Braune and Fischer’s intricate efforts to prepare the military recruit for his mission correspond nicely with the mathematical contortions required to translate the image into acceptable scientific data. Understanding the mechanics of the human body required its submission and disassembly on both sides of the equation, before and after the chronophotographic inscription.6

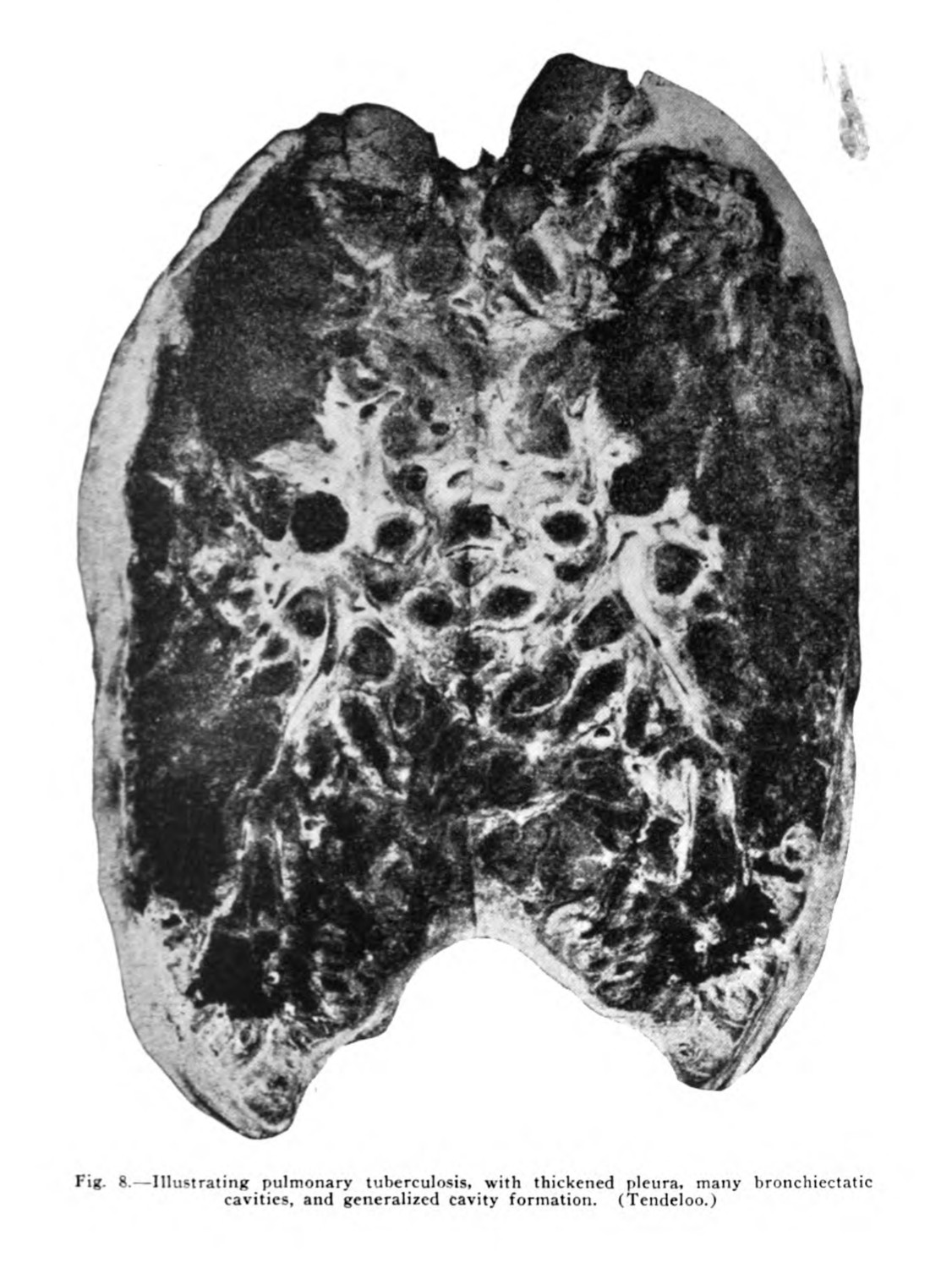

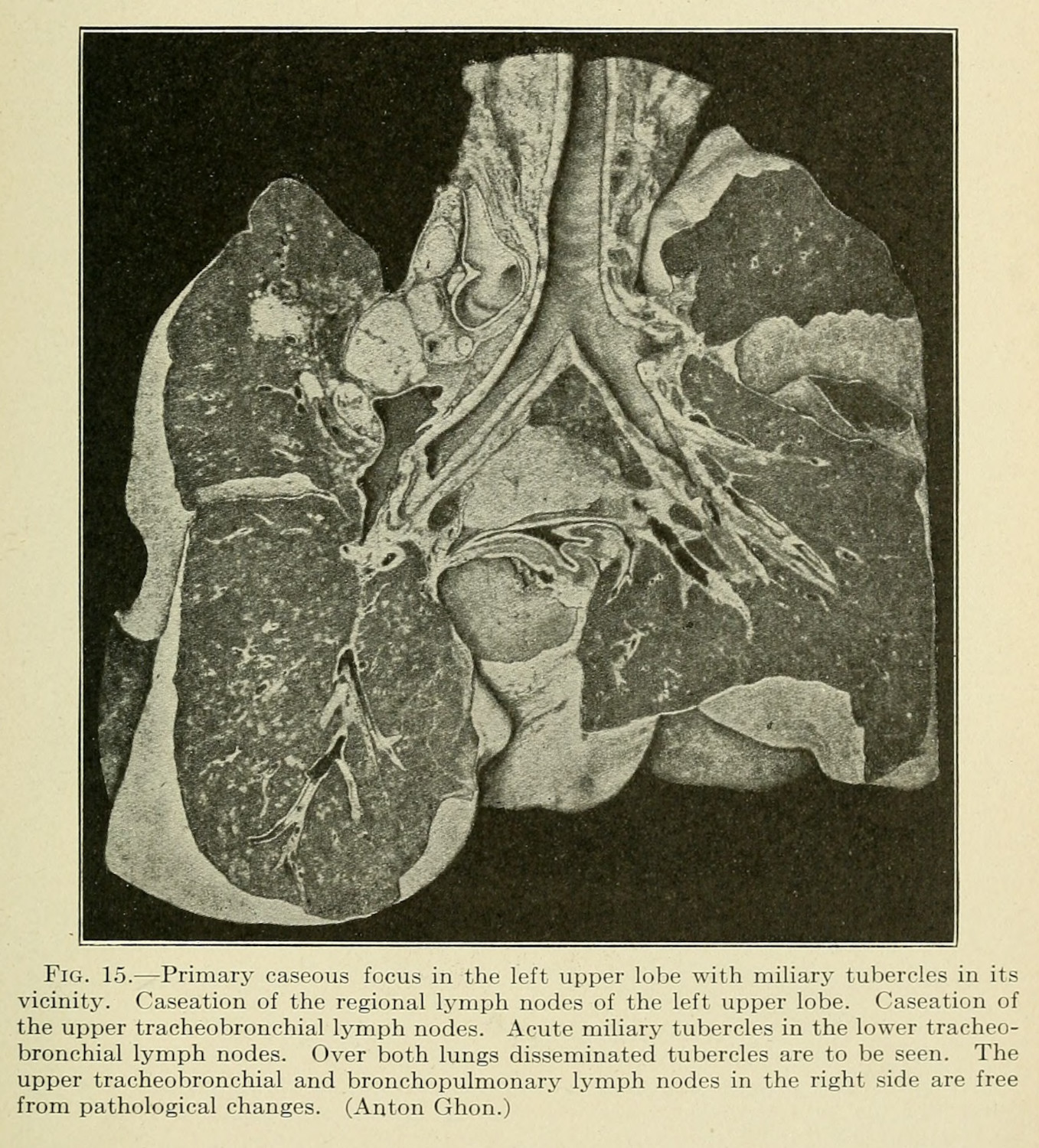

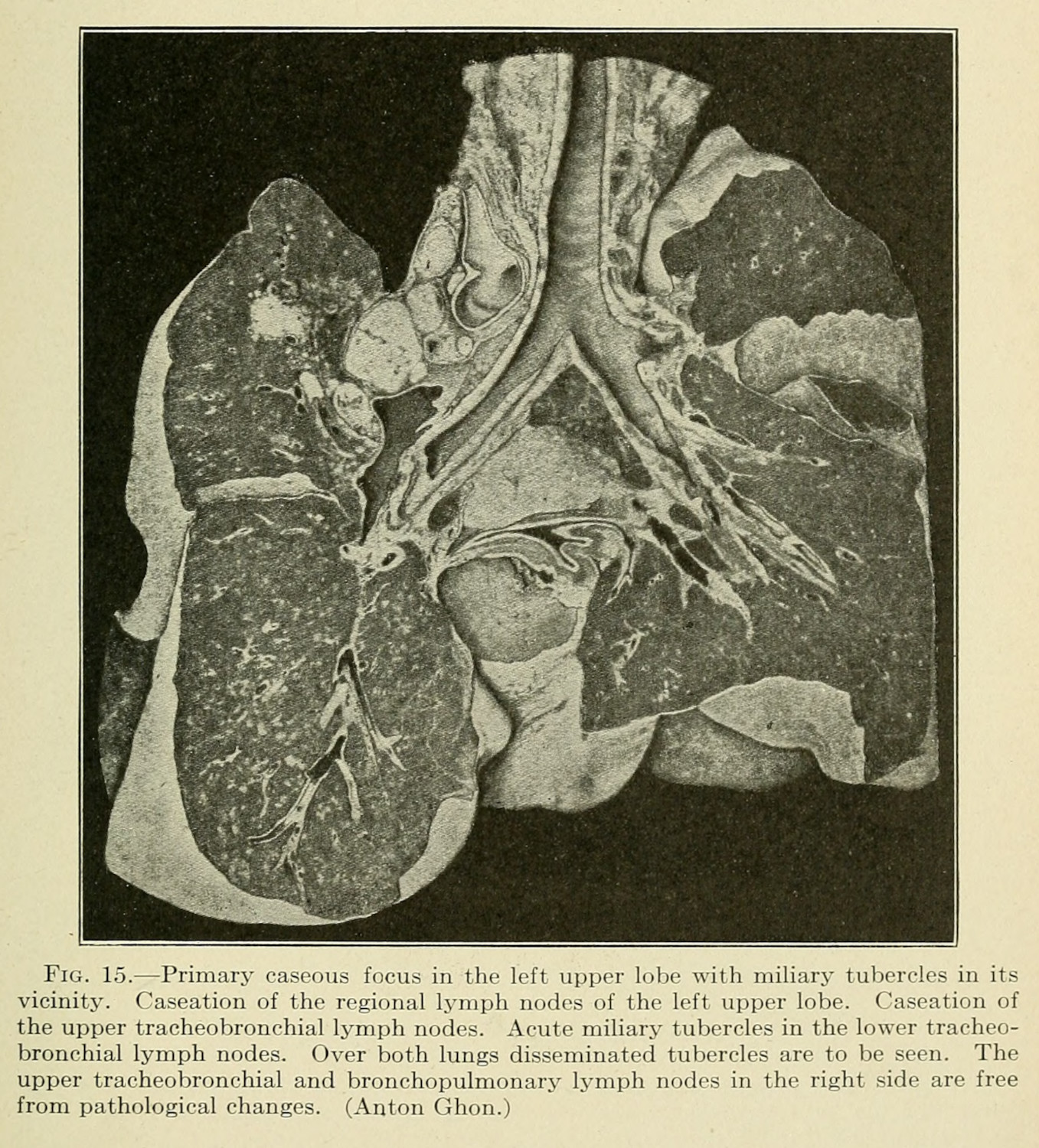

In regard to wet specimens, the disciplining has less to do with unruly patients or research subjects, so much as it had to do with the complex processes that made pathologies visible, often requiring a material intervention upon a patient’s corpse. If patients have to be held in place to capture the physiognomy of a disease on their body (1.4.2), then so too do they need to be excavated—cut apart with bone saws and scalpels—and then made stable—through photography or formalin—to produce evidence for scientific claims (fig. 5).

This argument has disciplinary valences within media studies and science and technology studies (STS): to attend to the construction of images, we scholars need to be cognizant of the extended histories of those material artifacts.7 Markings are stratified in time: tuberculosis’ marks upon the body—through tubercles, Pott’s disease, or other pathological manifestations—the doctor’s cuts which disassemble the body, and the pins which reveal and pose relevant information.

This thinking follows the way Jacque Derrida thinks about the archive, as a space of inscription and circumcision. Derrida’s description of circumcision aids in my approach to an archive’s material culture. As a discursive institution, whose fragments support particular political and personal goals, the archive is also a space of cultural, historical sedimentation. In an uncharacteristic moment of clarity around a single archival object, Sigmund Freud’s family bible and the inscription written by the psychoanalyst’s father, Derrida describes how the residual, historical, inscriptive possibility of the archive is enacted:

A gift carried this inscription. What the father gives to the son is at once a writing and its substrate. The substrate, in a sense, was the Bible itself, the ‘Book of books,’ a Philippsohn Bible Sigmund had studied in his youth. His father restores it to him, after having made a present of it to him; he restitutes it as a gift, with a new leather binding. To bind anew: this is an act of love. Of paternal love.8

This seemingly out of place archival artifact,9 becomes a nested, entangled symbol of patriarchal, religious, and material significance. The object’s compounding cultural residues—which both defines it as worthy of preservation and aligns it as an outlier in the primary historical record—envelop it in an abject ganglion of emotional weight, personal value, historical significance, and discursive relevance.

For wet specimens, there is a material intervention upon the object’s skin;10 the pathologist excises and extirpates unwanted material to reveal something about the object, and in doing so inscribes that meaning for subsequent viewers. The cut is a mark, a means of writing.11 Inscription, in this sense, produces arguments and also produces medical science’s authoritative objects.12

Especially in regard to pathological specimens that represent disease, they necessarily need to come from a research subject whose personal history and case history is entwined with a disease (2.2.3). The circumcised history of the disease on the flesh of the research subject is the valuable research object which scientists try to extract. For my argument in this chapter, it is the circumcised history of a scientist’s actions that are what I am trying to extract.13 The production of value in medical sciences depends on this relationship between the patient turned research subject’s history, and the disciplining of their body in life and after death. The marks and cuts, the retention and discard of material, all produce an object that seems so simply able to convey an argument: this is what tuberculosis does within the body of a patient.

And so, the rest of this chapter looks to these research objects, which were taken from the bodies of human beings, which have been cut and scraped, preserved and photographed, and which represent the pathological effects of tuberculosis on the human body. These specimens{end} represent disease, but they also are circumcised with a patient’s history as well as the labor of making tuberculosis legible. To describe what I mean, I will first take the wet specimen as it is intended to be read, before turning to read it in relation (2.4.1).

My hope is to add an additional wrinkle to the conversation regarding how medical scientists are trained to see: they certainly extend a form of clinical visuality (1.1.2; 2.2.2), but that visuality in the case of published research is always mediated between technologies, patients, and the materiality of the patient’s body. So much of visual culture around specimens denies the presence of the human body in its entirety, something that certainly rhymes14 with Michel Foucault’s clinical vision, but which demands additional inspection, precisely because in the production of specimens there is also a production of epistemic, institutional, and cultural value (0.1.4).

The chorus of this case study is: these objects were people once. My central argument will be to stress the continuity between living subject and inert matter. With this mind, I will first think through how clinical visuality, ala Foucault, severs this connection, before attending to some of the extant problems with new materialism (2.4.2).

-

There too is a practice of medical students being photographed while posing with their anatomical cadavers.

Warner, John Harley. “The Aesthetic Grounding of Modern Medicine.” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 88, no. 1 (Spring 2014): 1–47. ↩

-

Although, presumably, over time this kind of study would become more difficult as the cellular structures decay. It is also worth noting that while the material is preserved in some way through submersion in spirit, some information, like DNA, is not maintained. ↩

-

Bennett, Jane. “Systems and Things: A Response to Graham Harman and Timothy Morton.” Source: New Literary History 43, no. 2 (2012): 225–33; Bennett, Jane. Vibrant Matter. Duke University Press, 2010. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822391623; Harman, Graham. “Object-Oriented Ontology.” In Palgrave Handbook of Posthumanism in Film and Television, edited by MIcchael Hauskeller, Michael Carbonell, and Thomas D. Philbeck. London & New York: Palgrave MacMillan Limited, 2016; Latour, Bruno. “On Actor-Network Theory: A Few Clarifications Plus More Than a Few Complications.” Soziale Welt 47 (1996): 369–81; Latour, Bruno. “Agency at the Time of the Anthropocene.” New Literary History 45, no. 1 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1353/nlh.2014.0003; Chakrabarty, Dipesh. “Humanities in the Anthropocene: The Crisis of an Enduring Kantian Fable.” New Literary History 47, no. 2–3 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1353/nlh.2016.0019. ↩

-

Guins, Raiford. Game After: A Cultural Study of Video Game Afterlife. The MIT Press, 2014. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt9qf8c8; Jue, Melody. Wild Blue Media: Thinking Through Seawater. Durham & London: Duke University Press, 2020; Peters, John Durham. The Marvelous Clouds: Toward a Philosophy of Elemental Media. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015. ↩

-

Kopytoff, Igor. “The Cultural Biography of Things: Commoditization as Process.” In The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspectives, edited by Arjun Appadurai, 64–91. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986. ↩

-

Curtis, Scott. The Shape of Spectatorship: Art, Science, and Early Cinema in Germany. New York: Columbia University Press, 2015. 38. ↩

-

Purcell, Sean. “Rendering in Analog Games: Dissected Puzzles and Georgian Death Culture.” Game Studies 23, no. 1 (2023). ↩

-

Jacques Derrida. Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression trans. Eric Prenowitz. (Chicago: THe University of Chicago Press, 1999; orig. 1995), 21. ↩

-

Why would any history of psychology need to reference a bible? ↩

-

I use skin to point to the emotional, material, and felt relationship associated with skin.

Ahmed, Sara, and Jackie Stacey, eds. Thinking Through the Skin. London & New York: Routledge, 2001; Anzieu, Didier. The Skin Ego: A Psychoanalytic Approach to the Self. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1989; Lafrance, Marc. “Skin Studies: Past, Present and Future.” Body & Society 24, no. 1–2 (2018): 3–32; McMillan, Uri; “Introduction: Skin, Surface, Sensorium.” Women & Performance: A Journal of Feminist Theory, 2018, 1–15. ↩

-

Ahmed, Sara, and Jackie Stacey. “Introduction: Dermographies.” In Thinking Through the Skin, edited by Sara Ahmed and Jackie Stacey, 1–17. London & New York: Routledge, 2001. ↩

-

Latour, Bruno, and Steve Woolgar. Laboratory Life: The Construction of Scientific Facts. 2nd ed. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1986. ↩

-

Takemoto, Tina. “Open Wounds.” In Thinking Through the Skin, edited by Sarah Ahmed and Jackie Stacey, 104–23. London: Routledge, 2001. ↩