Introduction

Specimen Studies

0.1.1 | 0.1.2 | 0.1.3 | 0.1.4 | 0.1.5Methods

0.2.1 | 0.2.2The Structure of this Dissertation

0.3.1Tuberculosis' Visual Culture

Visual Practices in Medical Culture

1.1.1 | 1.1.2 | 1.1.3Seeing and Settling in the Sanatorium Movement

1.2.1 | 1.2.2 | 1.2.3 | 1.2.4 | 1.2.5Teaching Public Health

1.3.1 | 1.3.2 | 1.3.3 | 1.3.4 | 1.3.5Representing Doctors in Tuberculous Contexts

1.4.1 | 1.4.2Using Human Specimens in the Study of Tuberculosis

Seeing Disease in Methyl Violet

2.1.1 | 2.1.2 | 2.1.3 | 2.1.4Case Histories

2.2.1 | 2.2.2 | 2.2.3 | 2.2.4Visceral Processes

2.3.1 | 2.3.2Relation

2.4.1 | 2.4.2 | 2.4.3Arts-Based Inquiry

Introduction

3.1.1 | 3.1.2 | 3.1.3 | 3.1.4Terminal Imaginaries & Tuberculous Imaginaries

3.2.1 | 3.2.2 | 3.2.3 | 3.2.4 | 3.2.5 | 3.2.6Dermographic Opacities

3.3.1 | 3.3.2 | 3.3.3 | 3.3.4Tactical Pretensions

3.4.1 | 3.4.2 | 3.4.3Designing Opacity

A Shift towards the Anticolonial

4.1.1 | 4.1.2 | 4.1.3 | 4.1.4Refusals and Opacities

4.2.1 | 4.2.2 | 4.2.3 | 4.2.4Digital and Ethical Workflows

4.3.1 | 4.3.2 | 4.3.3 | 4.3.4 | 4.3.5Conclusion

4.4.1Coda

Prometheus Undone

5.1.1 | 5.1.2 | 5.1.3 | 5.1.4Appendix

The Tuberculosis Corpus

X.1.1 | X.1.2 | X.1.3Web Design

X.2.1 | X.2.2 | X.2.3 | X.2.4Installation Materials

X.3.1 | X.3.2 | X.3.3Index

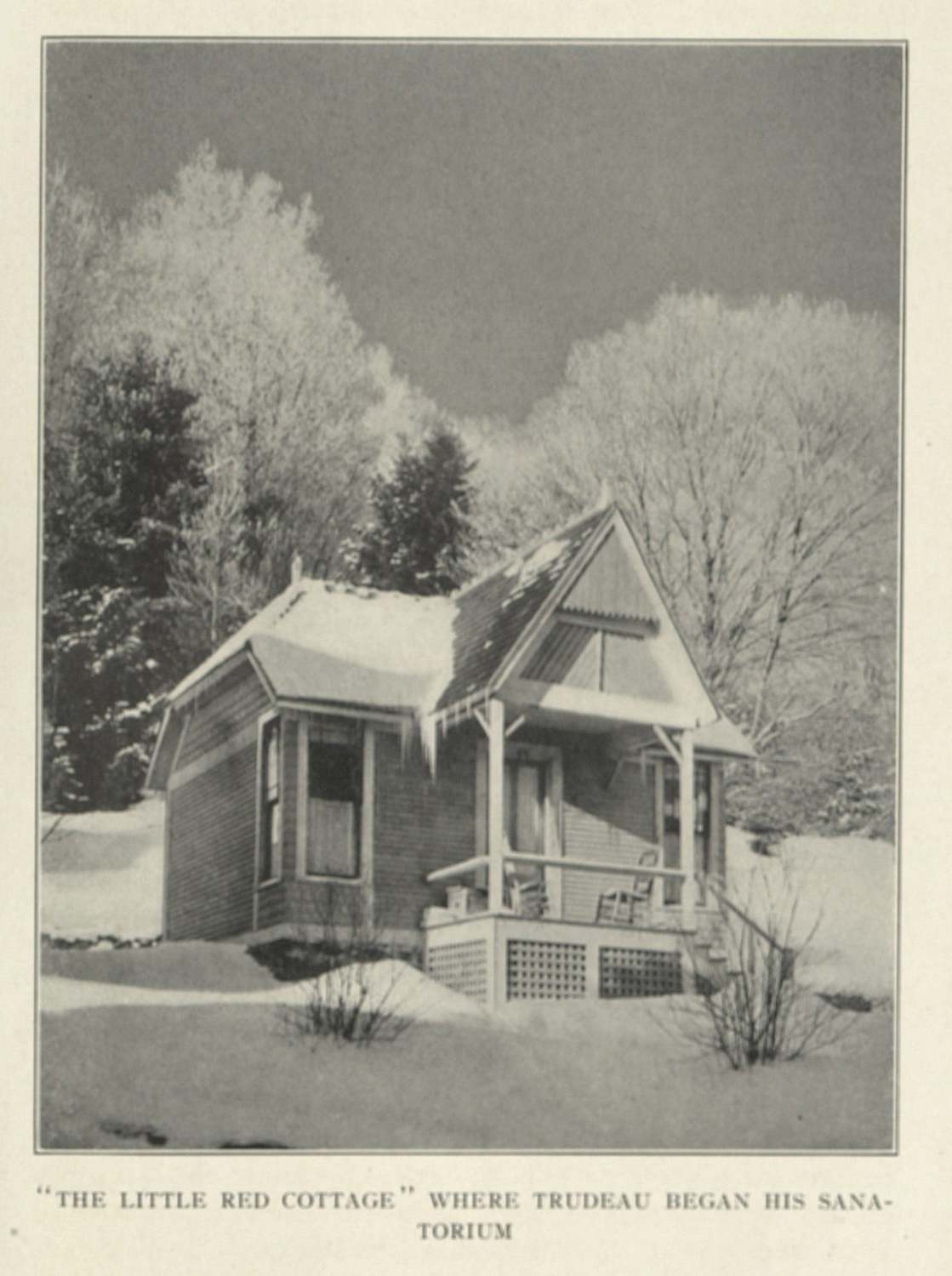

Edward Livingston Trudeau first moved to upstate New York in 1873. Trained as a doctor in New York City, he had worked at The Strangers’ Hospital before becoming infected with tuberculosis. Frail and feverish, Trudeau left his family in the city to rest and recover in the Adirondacks. Writing in his autobiography, he explained his decision:

I was influenced in my choice of the Adirondacks only by my love for the great forest and the wild life, and not at all because I thought the climate would be beneficial in any way, for the Adirondacks were then visited only by hunters and fishermen and it was looked upon as a rough, inaccessible region and considered a most inclement and trying climate. I had been . . . greatly attracted by the beautiful lakes, the great forest, the hunting and fishing, and the novelty of the free and wild life there. If I had but a short time to live, I yearned for surroundings that appealed to me, and it seemed to meet a longing I had for rest and the peace of the great wilderness.1

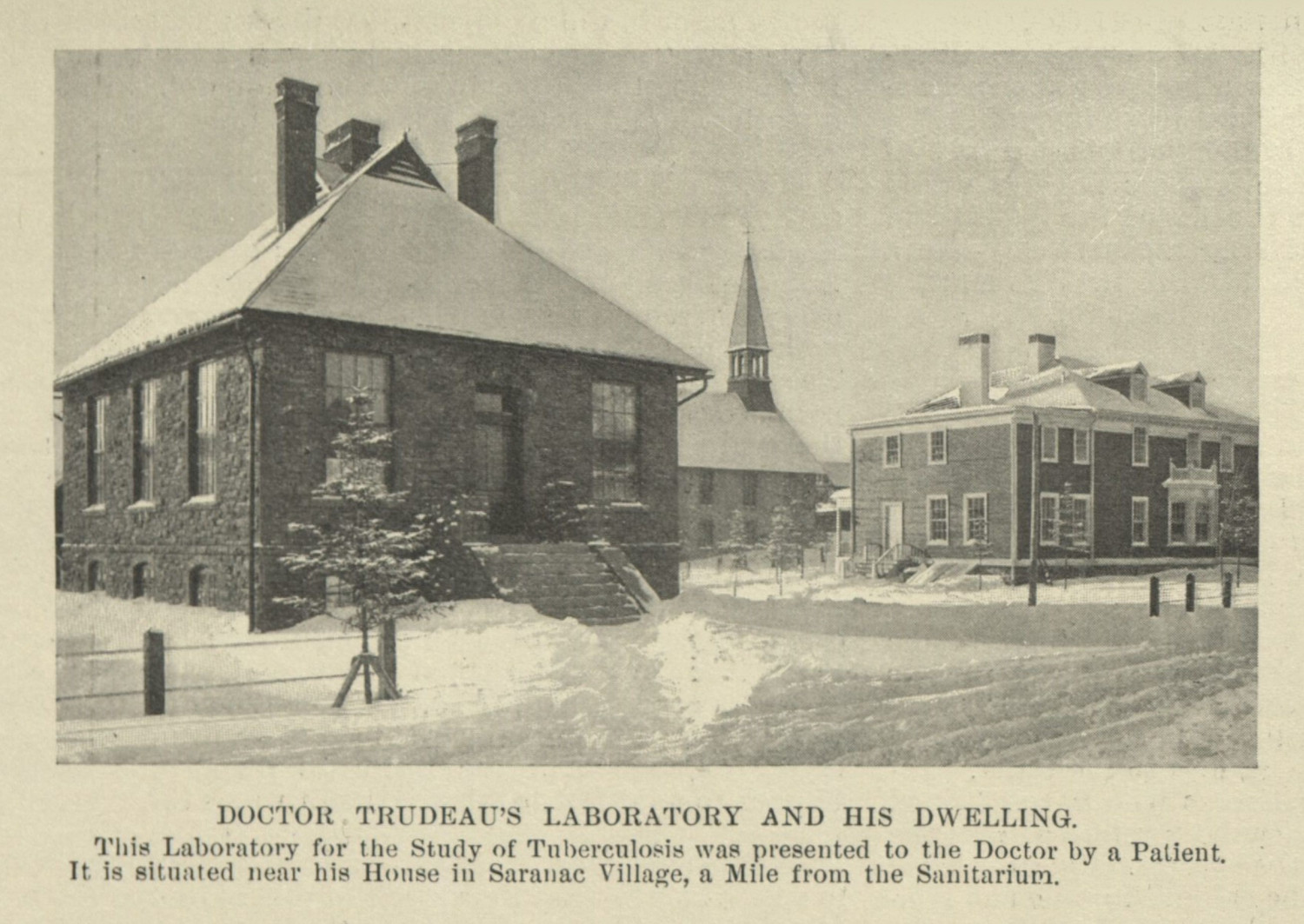

Figure 2. An image of the Adirondack Cottage Sanitarium’s laboratory. Image courtesy of the New York Academy of Medicine.

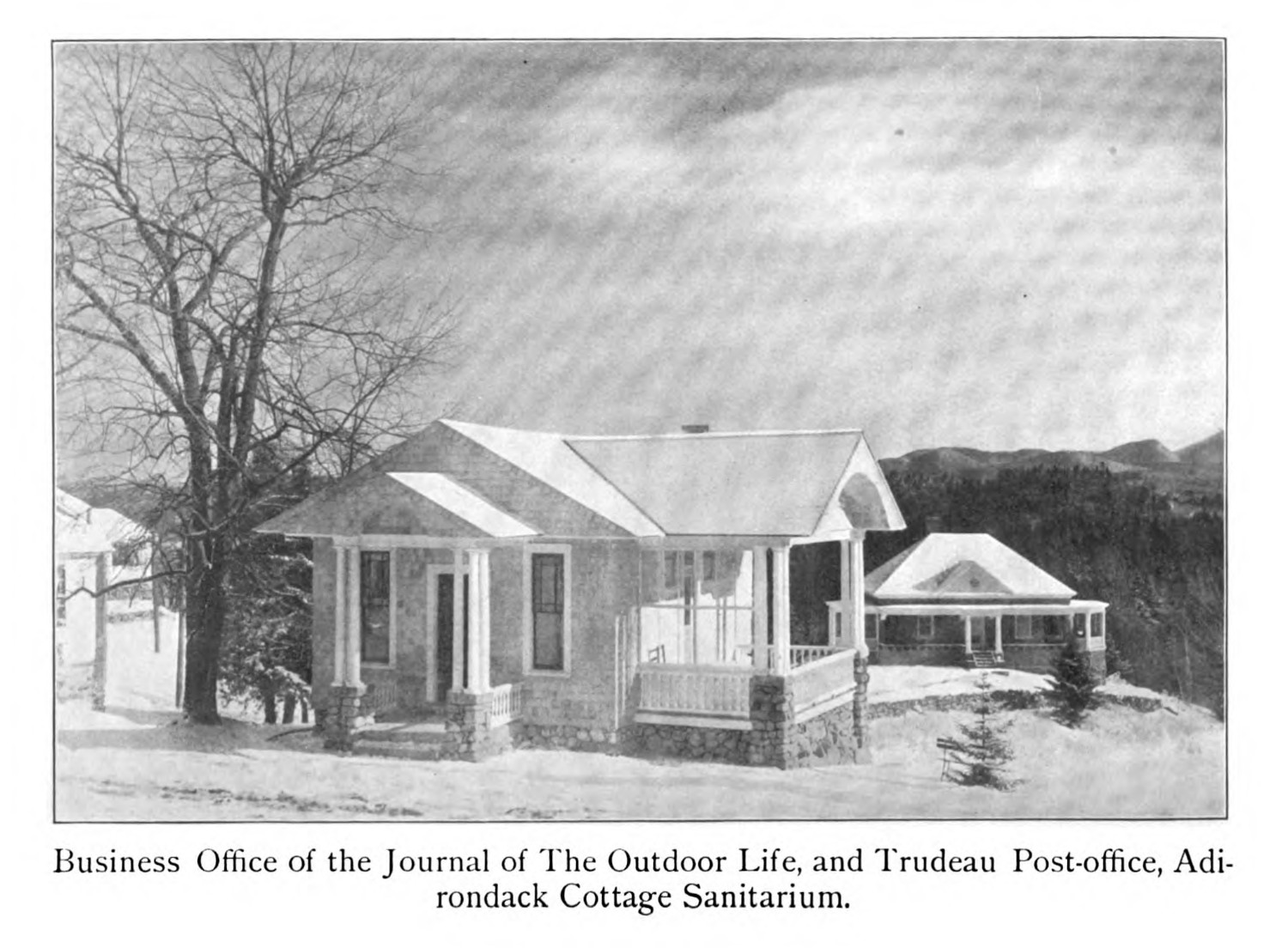

Figure 2. An image of the Adirondack Cottage Sanitarium’s laboratory. Image courtesy of the New York Academy of Medicine. Figure 3. Another image of the Adirondack Cottage Sanitarium. The Journal of the Outdoor Life: The Anti-Tuberculosis Magazine 3. New York: Trudeau Sanitarium, 1906.

Figure 3. Another image of the Adirondack Cottage Sanitarium. The Journal of the Outdoor Life: The Anti-Tuberculosis Magazine 3. New York: Trudeau Sanitarium, 1906.Accompanied by his friend Lou Livingston, Trudeau sought refuge at Paul Smith’s home in the Adirondacks, beginning a regimen of rest which resulted in a complete recovery over a number of years.

Upon getting better, Trudeau began entertaining the idea of building a sanatorium in the same place he had recovered, having come across a summary of Herman Bremer’s Sanitarium in a medical journal. Trudeau writes, “Brehmer was the originator of the sanitarium method, the essence of which was rest, fresh air and a daily regulation by the physician of the patient’s life and habits.”2 The rest cure, which was commonly used as a therapeutic method in the Americas, originates from this practice (1.2.2), and the usage of the term sanatorium is also indebted to a translation of the German word heilanstalt, or ‘healing place’. The word ‘sanatorium’ is linked to heilanstalt through the use of the Latin words sanare—to heal—and sanitas—healthy.3 While modeled on Brehmer’s approach, the idea of an institution specifically suited for consumptive patients had already been put into practice in England. In 1836 George Bodington opened the doors of his consumptive sanatorium and asylum in Birmingham.4 These institutions, built on assumptions about the curative qualities of climate (1.2.2; 1.3.2) or the medicinal qualities of specific waters or springs, existed long before the sanatorium craze. Many still exist today.

The Adirondack Cottage Sanitarium was built on this lineage and added a non-profit emphasis; patients who could not afford care were charged less. After its opening in 1885, the institution grew slowly, both in terms of how many patients it could hold, but also in terms of its research facilities. By 1900 it had become the most culturally and scientifically important sanatorium in this period. This historical impact can be seen in the many times the sanatorium’s buildings can be seen throughout the tuberculosis corpus (figs. 1 -3; also many of the images in this section) (X.1.3).

In the years following the opening of Trudeau’s sanatorium, hundreds of similar institutions opened their doors for patients. This first case study examines the visual materials produced by and for these newly built institutions. The rise of the sanatorium, as it was represented in both popular and scientific discourses around tuberculosis, shows a surprising visual focus away from the disease itself and toward the spaces and environments of healing. These photographs and illustrations seem to go against the overarching conceit regarding vision (1.1.2; 2.2.2). These images operate on a different visual field and point to parallel developments in medical epistemics and health culture. Their outsized presence in the tuberculosis corpus with more than 25% of the images representing an architectural space, demands the attention of contemporary scholars (table 1) (X.1.1; X.1.3).

The sanatorium itself and the discourses around its popular emergence presented an ideal for health that was entwined with property development (1.2.4; 1.2.5). Sometimes images of these institutions were found in advertisements-as-articles in the pages of medical journals (1.2.3) and other times they were located in directories for patients with tuberculosis (1.2.3). These images correspond to an emerging relationship between the patient and the health care system that bound patient improvement to the idyllic, clean, technologically advanced, and stately health resort. Both the construction of an image around the sanatorium—as a health spa, a Romantic getaway (1.2.2), a space of healing—and the healing associated with those spaces of care, seemed to matter more than any curative practice. There is a link between sanatoria, the growing and professionalizing American medical discipline, and an overt expansionism in medicine associated with the creation of medical facilities.

| Advertisement | 15 |

|---|---|

| Anatomical | 257 |

| Animal Specimen | 78 |

| Architectural | 1104 |

| Architecture | 3 |

| At Work | 50 |

| Child | 326 |

| Diagnostic | 199 |

| Equipment | 421 |

| Exhibition | 65 |

| Graphical | 8 |

| Group | 412 |

| Hygiene | 126 |

| Institutional | 36 |

| Instructive | 98 |

| Map | 4 |

| Microscopic | 238 |

| Organ | 310 |

| Other | 167 |

| Pathological | 1244 |

| Portrait | 751 |

| Professional | 57 |

| Sensitive | 110 |

| Treatment | 313 |

Table 1. A collection of all unique tags in the image dataset. 4056 of the images have been tagged for this data.

-

Trudeau, Edward Livingston. An Autobiography. Garden City & New York: Doubleday, Doran & Company, Inc., 1944. 77-78. ↩

-

Ibid., 154. ↩

-

Daniel, T. M. “Hermann Brehmer and the Origins of Tuberculosis Sanatoria.” International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease 15, no. 2 (2011): 161–62. ↩

-

Bodington, George. An Essay on the Treatment and Cure of Pulmonary Consumption, on Principles Natural, Rational, and Successful: With Suggestions for an Improved Plan of Treatment of the Disease Amongst the Lower Classes of Society; and a Relation of Several Successive Cases Restored from Last Stage of Consumption to a Good State of Health. London: Longman, Orme, Brown, Green, & Longmans, 1840. ↩