Introduction

Specimen Studies

0.1.1 | 0.1.2 | 0.1.3 | 0.1.4 | 0.1.5Methods

0.2.1 | 0.2.2The Structure of this Dissertation

0.3.1Tuberculosis' Visual Culture

Visual Practices in Medical Culture

1.1.1 | 1.1.2 | 1.1.3Seeing and Settling in the Sanatorium Movement

1.2.1 | 1.2.2 | 1.2.3 | 1.2.4 | 1.2.5Teaching Public Health

1.3.1 | 1.3.2 | 1.3.3 | 1.3.4 | 1.3.5Representing Doctors in Tuberculous Contexts

1.4.1 | 1.4.2Using Human Specimens in the Study of Tuberculosis

Seeing Disease in Methyl Violet

2.1.1 | 2.1.2 | 2.1.3 | 2.1.4Case Histories

2.2.1 | 2.2.2 | 2.2.3 | 2.2.4Visceral Processes

2.3.1 | 2.3.2Relation

2.4.1 | 2.4.2 | 2.4.3Arts-Based Inquiry

Introduction

3.1.1 | 3.1.2 | 3.1.3 | 3.1.4Terminal Imaginaries & Tuberculous Imaginaries

3.2.1 | 3.2.2 | 3.2.3 | 3.2.4 | 3.2.5 | 3.2.6Dermographic Opacities

3.3.1 | 3.3.2 | 3.3.3 | 3.3.4Tactical Pretensions

3.4.1 | 3.4.2 | 3.4.3Designing Opacity

A Shift towards the Anticolonial

4.1.1 | 4.1.2 | 4.1.3 | 4.1.4Refusals and Opacities

4.2.1 | 4.2.2 | 4.2.3 | 4.2.4Digital and Ethical Workflows

4.3.1 | 4.3.2 | 4.3.3 | 4.3.4 | 4.3.5Conclusion

4.4.1Coda

Prometheus Undone

5.1.1 | 5.1.2 | 5.1.3 | 5.1.4Appendix

The Tuberculosis Corpus

X.1.1 | X.1.2 | X.1.3Web Design

X.2.1 | X.2.2 | X.2.3 | X.2.4Installation Materials

X.3.1 | X.3.2 | X.3.3Index

In 1905, a man was lying in a hospital bed at the Henry Phipps Institute in Philadelphia, slowly dying of meningeal tuberculosis. His death was documented, but his identity was stripped from the record, so I only know him as “Case No. 3440”.1 His death was documented in fragmented ways, starting with a family and personal history:

Two sisters had died of pulmonary tuberculosis. The patient had had the usual diseases of childhood; pleurisy sixteen months ago; and gonorrhea five years ago. He had had pulmonary tuberculosis for the last sixteen months, and presented milliary involvement of the entire right lung and of the upper lobe of the left lung. The pulmonary condition advanced during the two months at the Institute, with, however, gradual reduction in temperature, which varied between 101° and 102°F. The examination of the urine showed acidity, specific gravity Ioz2 (sic), a slight trace of albumin, no sugar, diazo reaction positive, and a few granular and wax-like casts. The patient had two slight hemorrhages, one on July 12th and one on July 24th.

Dover’s powder had been administered on August 1st. On August 2nd he had convulsions, Jacksonian in type, beginning in the left arm. He did not complain of headaches, and rested in fairly good condition until August 3rd, when he had another convulsion. On August 4th there is a record of four convulsions; on August 5th, seven; August 6th, nine; August 7th, thirty-seven; August 8th, fifty; August 9th, fifteen; August 10th, twenty-five, and August 11th, thirty. On August 7th complete paralysis of the right arm and leg developed, with complete loss of power in the right face.2

3440’s case is broken apart into a list of observations: patient history and family history, with specific interest in past disease. This is also a history of tuberculosis in the man’s body, its gains and retreats, with documented changes in weight, temperature and urine acidity. Catalogued in this documentation are symptoms—hemorrhages, seizures, paralysis—which advance in seriousness until they abruptly end when the patient dies. After the narrative of decline, an autopsy is described:

The notes of the examination are as follows:

“The patient is conscious, understands what is said to him, and obeys simple commands, such as protruding the tongue, closing the eyes, lifting the arm, etc. He is able to repeat simple words, such as ‘yes’ and ‘no,’ but is unable to hold articulate conversation. The right arm and leg are completely paralyzed and flaccid. The left arm and leg have apparently normal power. The knee-jerk on the paralyzed side is present and quick and weak. There is no ankle clonus on either side. The Babinski reflex is present on the right side. There is some hyperesthesia of the right side. Flexing the arm or the leg produces pain. The pupils are unequal, both more than middle wide, and the left larger than the right. There is no rigidity of the muscles of the neck to-day (slight rigidity was noted in the examination on August 8, 1905). Immediately after the examination the patient had a convulsion which began with slight moaning and clonic jerkings beginning in the right hand and extending rapidly to the face and leg of the right side. The head was turned to the right and the right eye was closed by a clonic spasm of the orbicularis. Both eyes were rotated to the right. During the convulsions he placed his left hand on the twitching mouth. There is some question as to whether consciousness was entirely lost on account of this movement. There were slight twitchings of the muscles of the face. He responded to simple commands immediately after the convulsive movements ceased. If consciousness was lost, it was only momentary. In an attempt to close the eyes in response to a command immediately after a convulsion, the right eye did not close entirely, showing some weakness.

“The diagnosis rests between a localized infiltrating tuberculous lesion confined to the left hemisphere, cerebral hemorrhage, and uremia. The history of the onset points to uremia. The examination of the urine at this time showed only a slight trace of albumin, specific gravity Io26. The mental condition, pulse, and general examination are also against the diagnosis of uremia. The onset, the mental condition, and the localized convulsions are against the diagnosis of cerebral hemorrhage, and therefore in favor of a diagnosis of a localized inflammatory infiltrating tuberculous process of the left cerebral hemisphere.”3

What interests me about this case study is the way it depicts a history. I use the term ‘history’ to note the connection between the term in medical diagnosis—the ways familial illness, and a subject’s past illness can help reveal something about the current malady—and the way the term is used in positivistic inquiries into the past, as it is in the discipline of History. Particularly, I think of the way Saidya Hartman does history, in reading against the archive to find gaps and address systemic, discursive violence. She writes

Is it possible to exceed or negotiate the constitutive limits of the archive? By advancing a series of speculative arguments and exploring the capacities of the subjunctive . . . in fashioning a narrative, which is based upon archival research, and by that I mean a critical reading of the archive that mimes the figurative dimensions of history, I intended both to tell an impossible story and to amplifying the impossibility of its telling.4

I think about 3440, and the way he died in a hospital bed while doctors and nurses tended to him, taking notes as they cared for him. I think about the way he died and how the information that is valuable to medical research is so incongruous with the lived experience of death (2.2.4). It reads as a line of symptoms, an apathetic written record of a subject who died under the care of the institute.

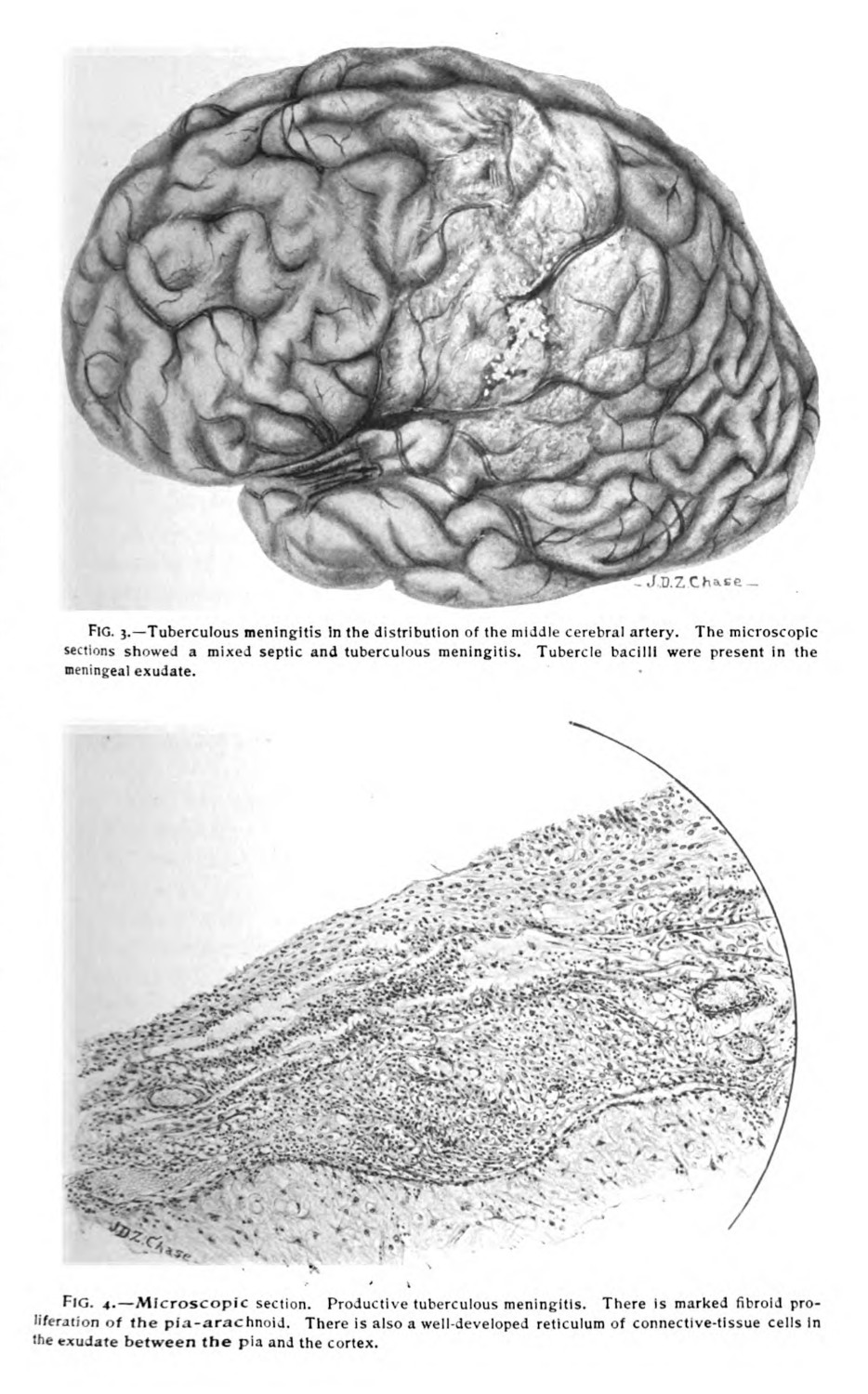

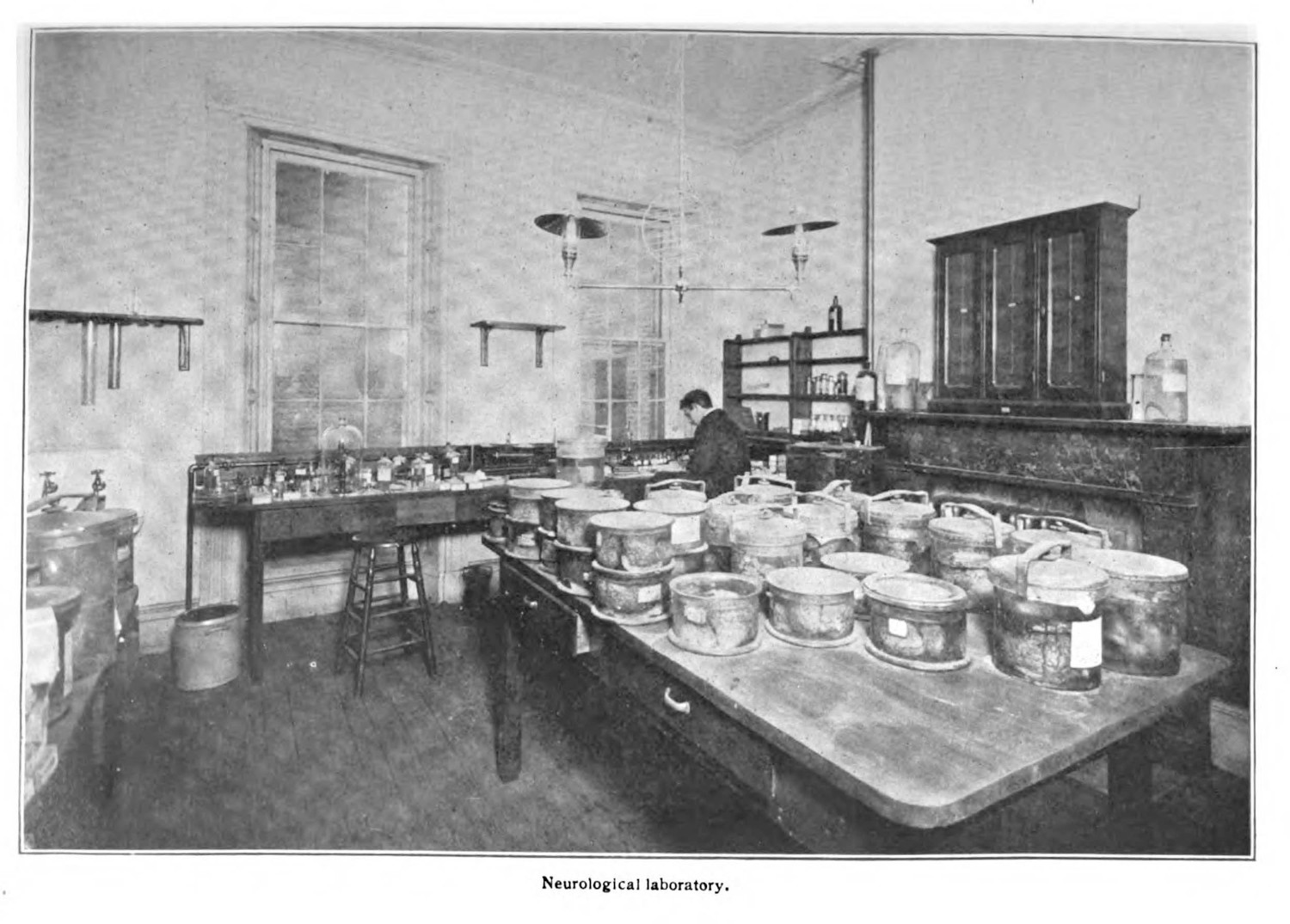

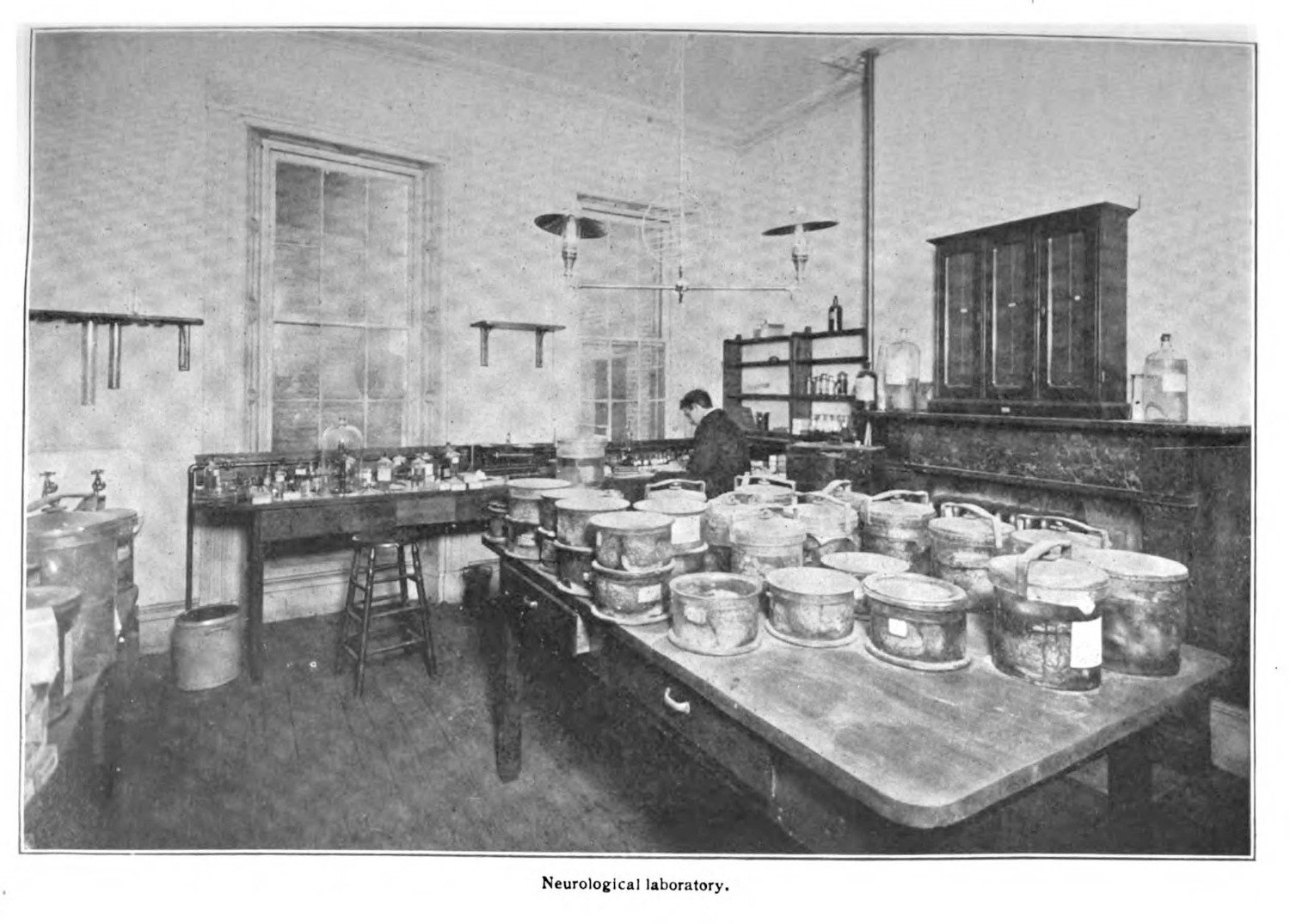

I use 3440’s history to describe in detail something I have been gesturing toward in this chapter, and which is central to this case study: that in order for the wet specimen to function, it needs to have some historical connection to the pathological phenomenon which the specimen reportedly shows. It is scientifically convincing to discuss the decline of patients with meningeal tuberculosis—a fast moving manifestation of a Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection which affected the brain and was colloquially called “galloping tuberculosis”—and then display, some pages later a brain of a patient who died of meningeal tuberculosis (fig. 1). While 3440 may not have been the exact subject whose brain was illustrated in the Phipps Institute’s annual report, I suspect it is imaged in the Institute’s neurology lab photograph (fig. 2) (0.1.1). The starkness of this narrative, which boils 3440’s death into 807 words in total,5 shows in part medicine’s reductionism,6 and with it, the aspects of the patient’s history which are deemed valuable for further research: the symptoms tied to the case history are in turn related to the embodied pathological evidence found at autopsy.

The individualistic approach to analysis in this case history is striking, partly because of the ways this narrative circumvents identification.7 Michel Foucault, in Discipline and Punish, describes the ‘case’ as a function of the individualizing power of discipline: “The case is no longer, as in casuistry or jurisprudence, a set of circumstances defining an act and capable of modifying the application of a rule; it is the individual as he may be described, judged, measured, compared with others, in his very individuality”.8 Working towards a critique of individualism—what he describes as a fabrication of discipline9—the case functions as a technology that produces discrete units of analysis:

The examination as the fixing, at once ritual and ‘scientific’, of individual differences, as the pinning down of each individual in his own particularity . . . clearly indicates the appearance of a new modality of power in which each individual receives as his status his own individuality, and in which he is linked by his status to the features, the measurements, the gaps, the ‘marks’ that characterize him and make him a ‘case’.10

Foucault’s approach to discipline—how it boxes, pins, isolates, contains, and through those modes of confinement define an object—articulates the case as a technology for this method, and the histories in medical texts correspond to this desire.

The case distills relevant information: 3440’s symptoms—embodied and aberrant events that signal the pathology—are narrated as a progression, but the agent seems both present and absent, a figment or a haunting.11 Important for this pathological-clinical method is that the value is projected at the recognition of symptoms (0.1.4): if there is something abnormal occurring within their body—abnormal specifically in the pathological sense, insomuch as it signals embodied difference (2.1.2)—then there is merit to documenting and collecting the material origin of that abnormality. Difference blooms infinitely, and each variation is epistemically valuable for doctors trying to understand the essentialist root of the phenomenon. In grasping a kind of totality of the pathology, which perfectly summarizes cause and effect in the patient’s body, there is always a demand for more knowledge—more unique cases, more unique specimens, more examples with which to compare (5.1.2).12

Symptomatic histories, familial histories, and case histories are bound to these objects, often explicitly stated. These histories are disciplined, insomuch as they only contain the valuable information to the academic disciplines for which they were collected. They work in conjunction with the material extracted from a patient’s body to comprehend the pathologies occurring within; they reinforce the potential value which can be taken at autopsy. They provide a frame to explain the pathological phenomenon.

-

I use this case study because I spent time thinking about it for my Tuberculous Imaginaries installation in May 2022 (4.2.4, X.3.2).

Purcell, Sean. Tuberculous Imaginaries. 2022. Three Projectors. https://tuberculousimaginaries.github.io/Installation/. ↩

-

Report of the Henry Phipps Institute for the Study, Treatment, and Prevention of Tuberculosis. Vol. 2. Philadelphia: Henry Phipps Institute, 1906. 95-96. ↩

-

96-97 ↩

-

Hartman, Saidiya. “Venus in Two Acts.” Small Axe 12, no. 2 (2008): 11. ↩

-

I have ommited some of this narrative for sake of space. ↩

-

I’ve looked for essays on medicine’s desire to reduce, but have not read anything I can whole heartedly recommend.

Miles, Andrew. “On Medicine of the Whole Person: Away from Scientific Reductionism and Towards the Embrace of the Complex in Clinical Practice.” Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice 15 (2009): 941–49. ↩

-

My suspicion is that anonymizing practices during this period are less interested in protecting patients from potential harm, as much as it is about protecting doctors. ↩

-

Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. New York: Vintage Books, 1995. 191. ↩

-

Ibid., 194. ↩

-

Ibid., 192. ↩

-

There may be something here, that I am not able to address, when speaking of haunted metaphors in medical practices.

Gordon, Avery F. Ghotstly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2008. ↩

-

Glissant, Édouard. Poetics of Relation. Translated by Betsy Wing. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1997. ↩