Introduction

Specimen Studies

0.1.1 | 0.1.2 | 0.1.3 | 0.1.4 | 0.1.5Methods

0.2.1 | 0.2.2The Structure of this Dissertation

0.3.1Tuberculosis' Visual Culture

Visual Practices in Medical Culture

1.1.1 | 1.1.2 | 1.1.3Seeing and Settling in the Sanatorium Movement

1.2.1 | 1.2.2 | 1.2.3 | 1.2.4 | 1.2.5Teaching Public Health

1.3.1 | 1.3.2 | 1.3.3 | 1.3.4 | 1.3.5Representing Doctors in Tuberculous Contexts

1.4.1 | 1.4.2Using Human Specimens in the Study of Tuberculosis

Seeing Disease in Methyl Violet

2.1.1 | 2.1.2 | 2.1.3 | 2.1.4Case Histories

2.2.1 | 2.2.2 | 2.2.3 | 2.2.4Visceral Processes

2.3.1 | 2.3.2Relation

2.4.1 | 2.4.2 | 2.4.3Arts-Based Inquiry

Introduction

3.1.1 | 3.1.2 | 3.1.3 | 3.1.4Terminal Imaginaries & Tuberculous Imaginaries

3.2.1 | 3.2.2 | 3.2.3 | 3.2.4 | 3.2.5 | 3.2.6Dermographic Opacities

3.3.1 | 3.3.2 | 3.3.3 | 3.3.4Tactical Pretensions

3.4.1 | 3.4.2 | 3.4.3Designing Opacity

A Shift towards the Anticolonial

4.1.1 | 4.1.2 | 4.1.3 | 4.1.4Refusals and Opacities

4.2.1 | 4.2.2 | 4.2.3 | 4.2.4Digital and Ethical Workflows

4.3.1 | 4.3.2 | 4.3.3 | 4.3.4 | 4.3.5Conclusion

4.4.1Coda

Prometheus Undone

5.1.1 | 5.1.2 | 5.1.3 | 5.1.4Appendix

The Tuberculosis Corpus

X.1.1 | X.1.2 | X.1.3Web Design

X.2.1 | X.2.2 | X.2.3 | X.2.4Installation Materials

X.3.1 | X.3.2 | X.3.3Index

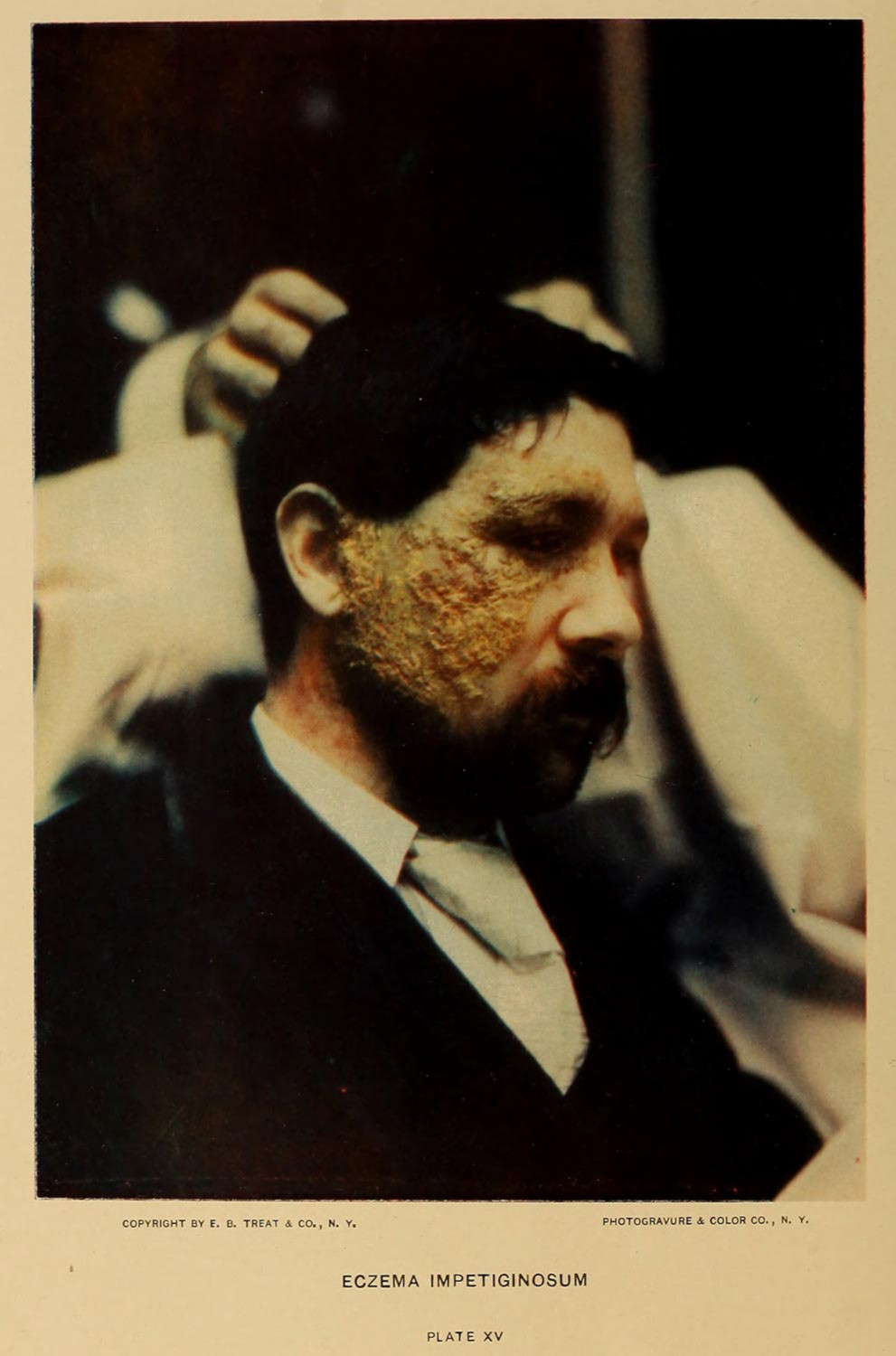

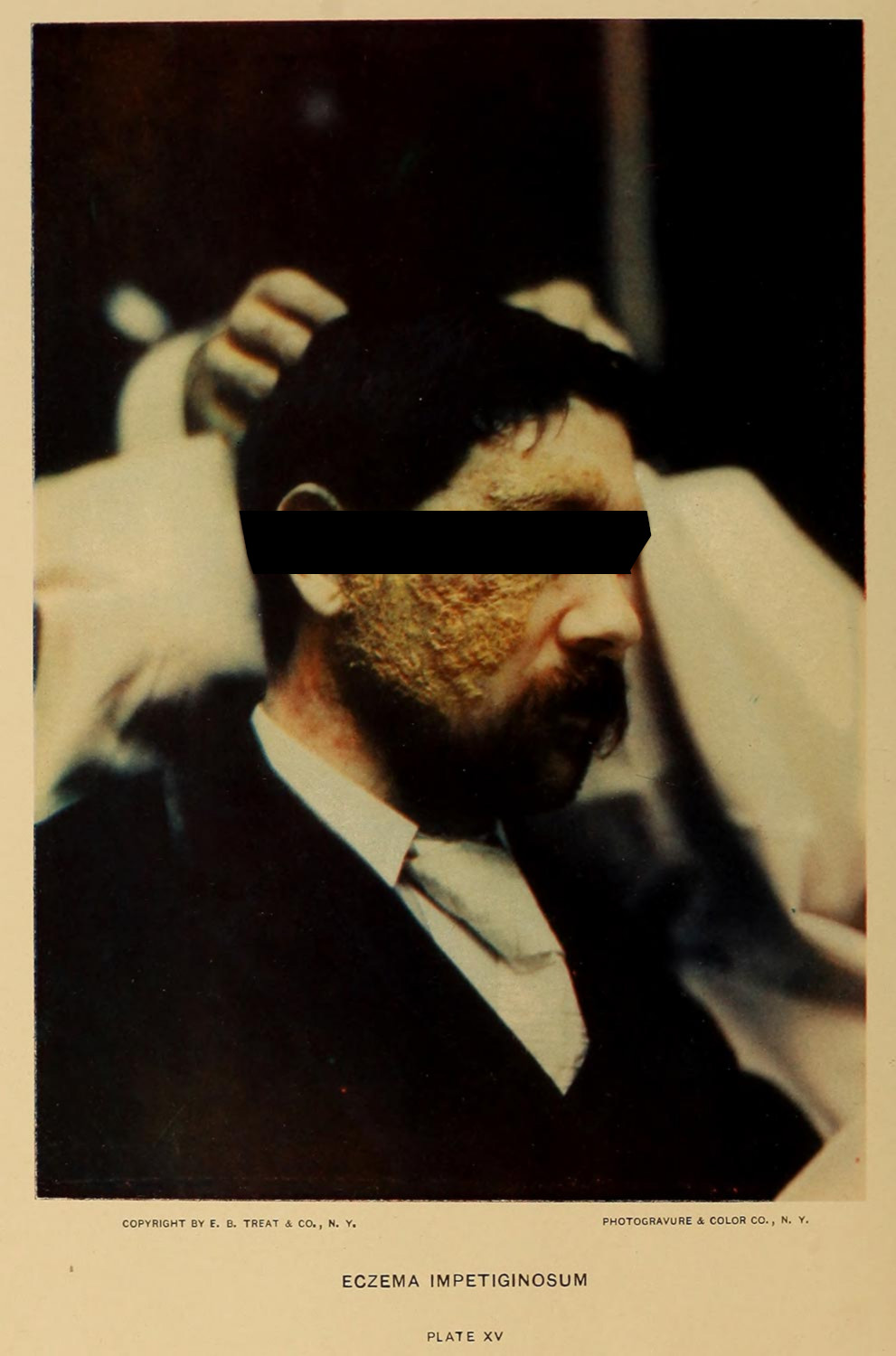

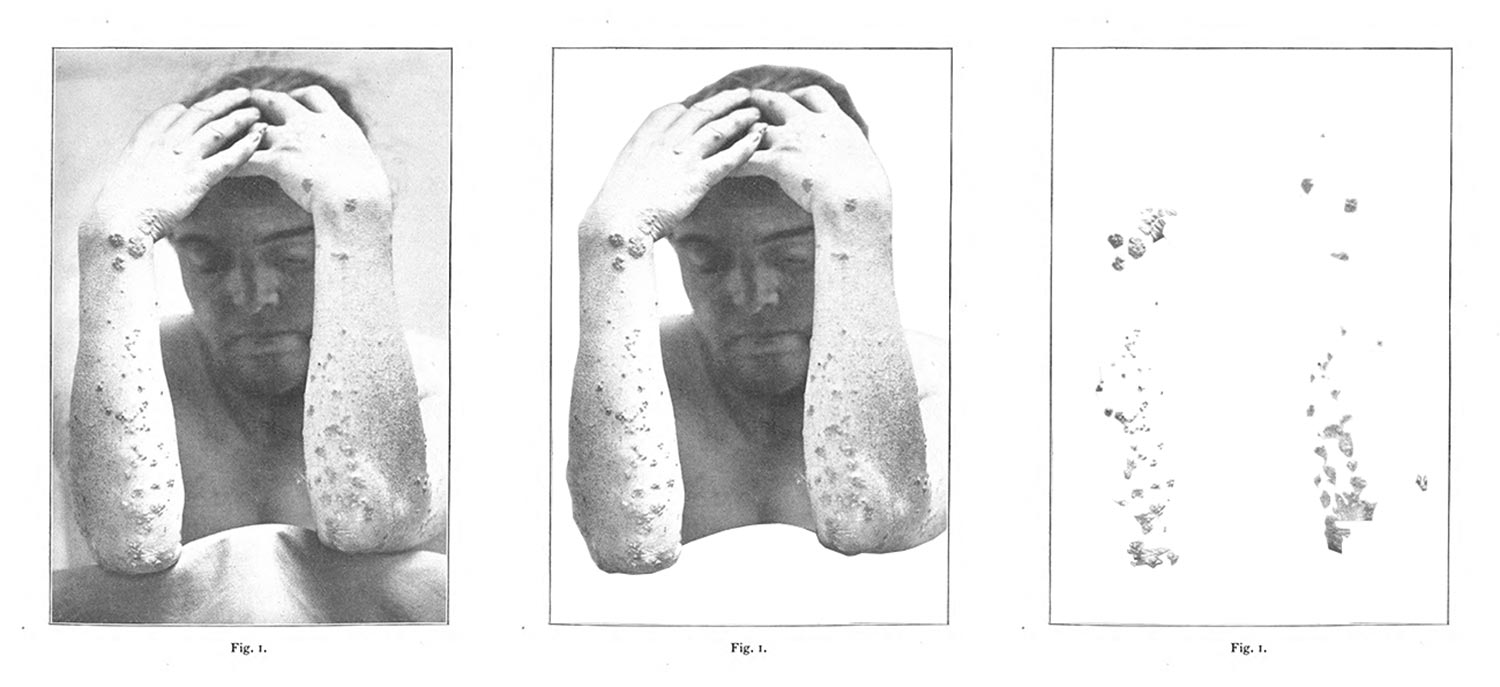

As I developed the .css and .html inputs, I spent time looking at images from the same collection of dermatological atlases that I had sampled from for Terminal Imaginaries (3.2.1). While returning to these texts, I created a brief list of selects. This is a process which I learned about from documentary video editing. Often with documentary footage, there is far too much material for one person to go over, and so usually an assistant editor will look over the totality of video collected for a project and flag takes or clips from that footage as being worthy of inspection by the main editor. These selects make the process of doing an assembly cut—or the first overly long edit with little to no care to the flow of the piece—more approachable.1 Through this process I began to think of the images in two ways: first, I started to train myself to try to see the interventions of doctors: their hands and tools which held a body still for examination (fig. 1) (1.4.2). I became interested in thinking of the various ways the bodies of patients were made docile for photographic capture (2.1.3).2

My second interest came by way of thinking through the Foucauldian notion of the clinical gaze—or the ocular practice that abstracts a patient’s symptoms against an idealized human anatomy, alienating and dehumanizing the patient in the process (1.1.2; 2.2.2). Just as the clinical gaze makes literal the objectification of the subject, it also makes literal the physiognomy of disease (2.3.2). The photographs seemed so interested in the visual recording of the disease, that the subject, their identity, and their dignity, seem secondary to the function of dermatological atlas. What struck me, and what still strikes me as I write this, is that there seemed to be a secondary connection between subject and object, a kind of root of the pathological condition which needed some context for it to function (2.2.3; 2.2.4). More simply, a photograph of a rash, like lupus vulgaris, may be helpful for a doctor, but it is more helpful if the doctor understands where on the patient it formed, and to what scale on their body it manifested. The context matters, and in the dermatological atlas this value supersedes any care and attention to the patient’s anonymity (2.2.4).

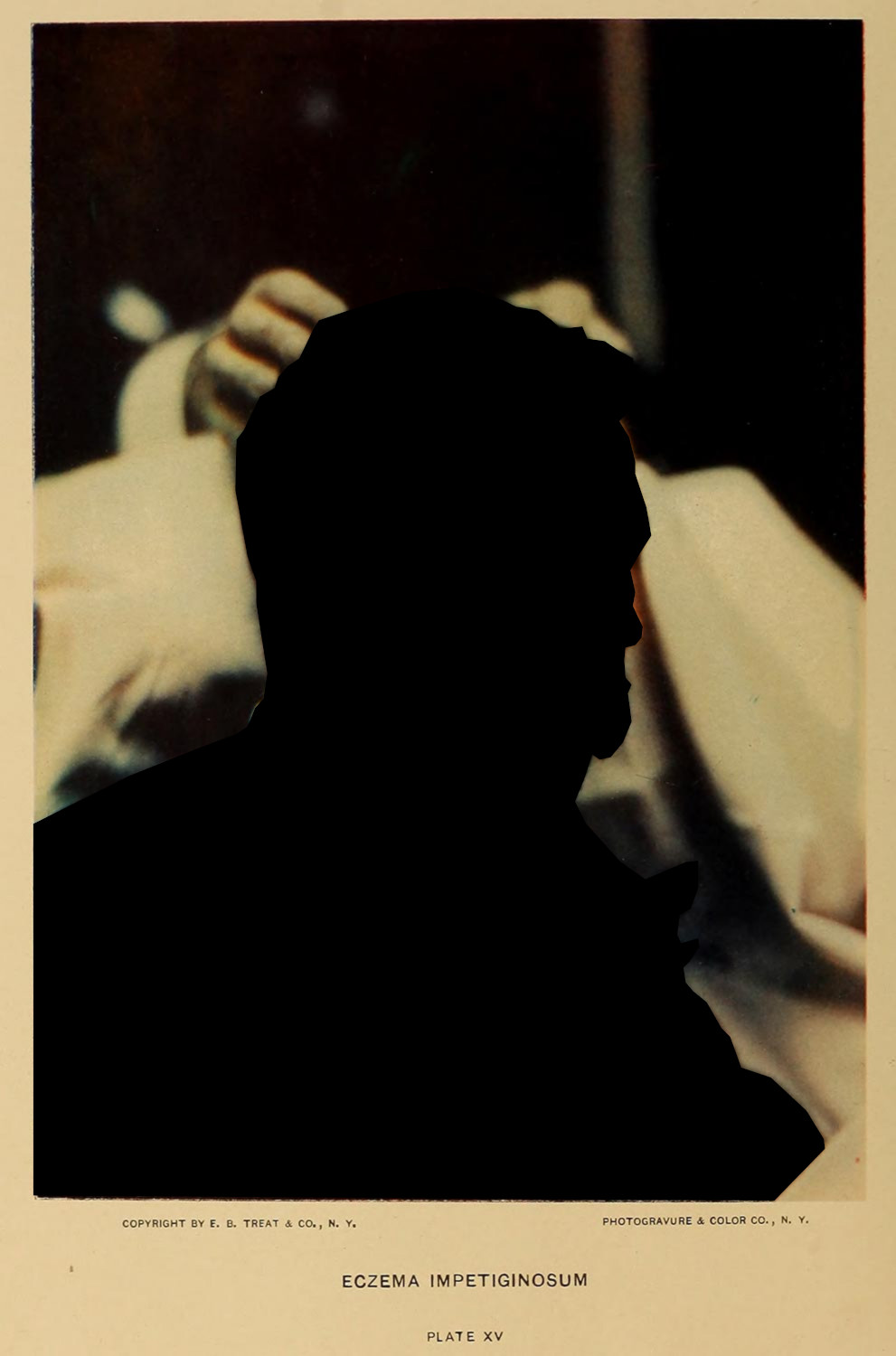

These two observations helped me layer opacities as a framing device. Where the previous installation, Terminal Imaginaries (3.2.1), thought through anonymity, or lack thereof, in the dermatological photograph, “Dermographic Opacities” began a strand of thinking whereby the absense of visual material could be leveraged to make an epistemic argument.

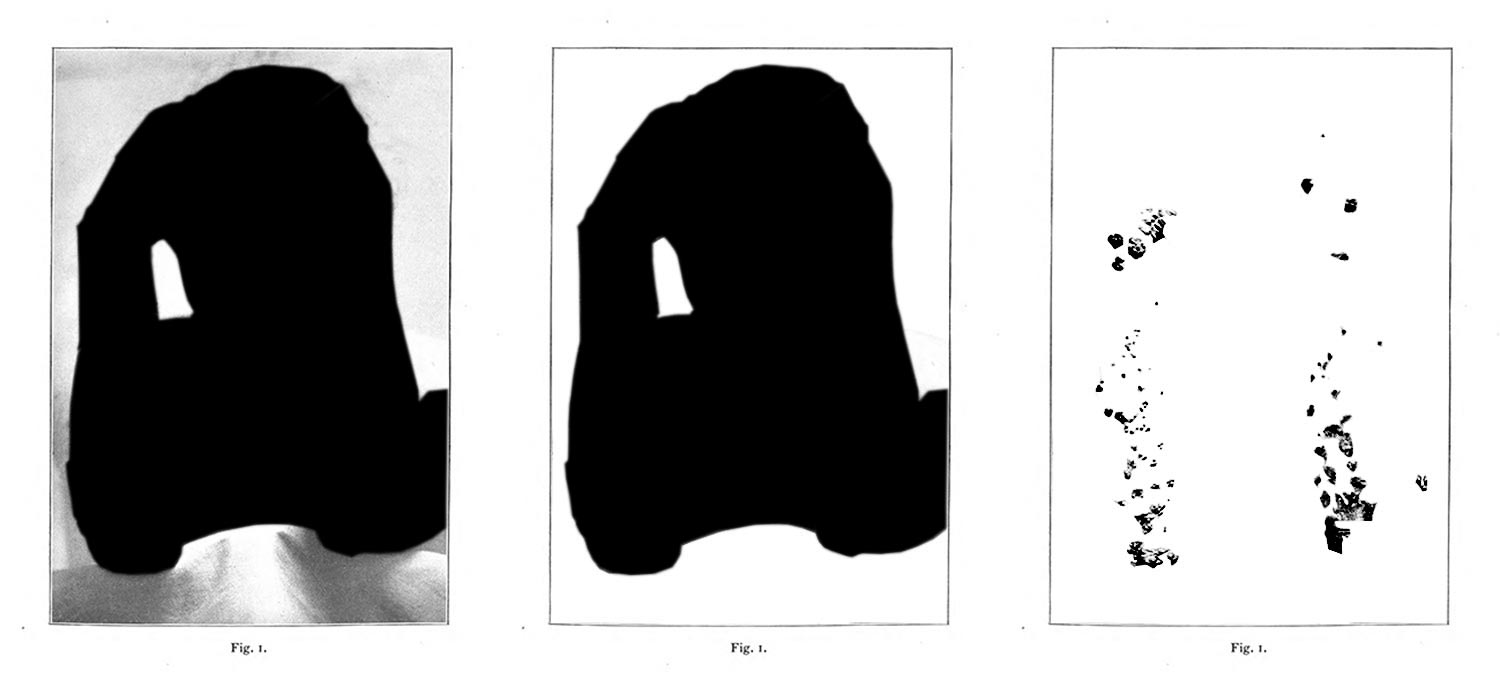

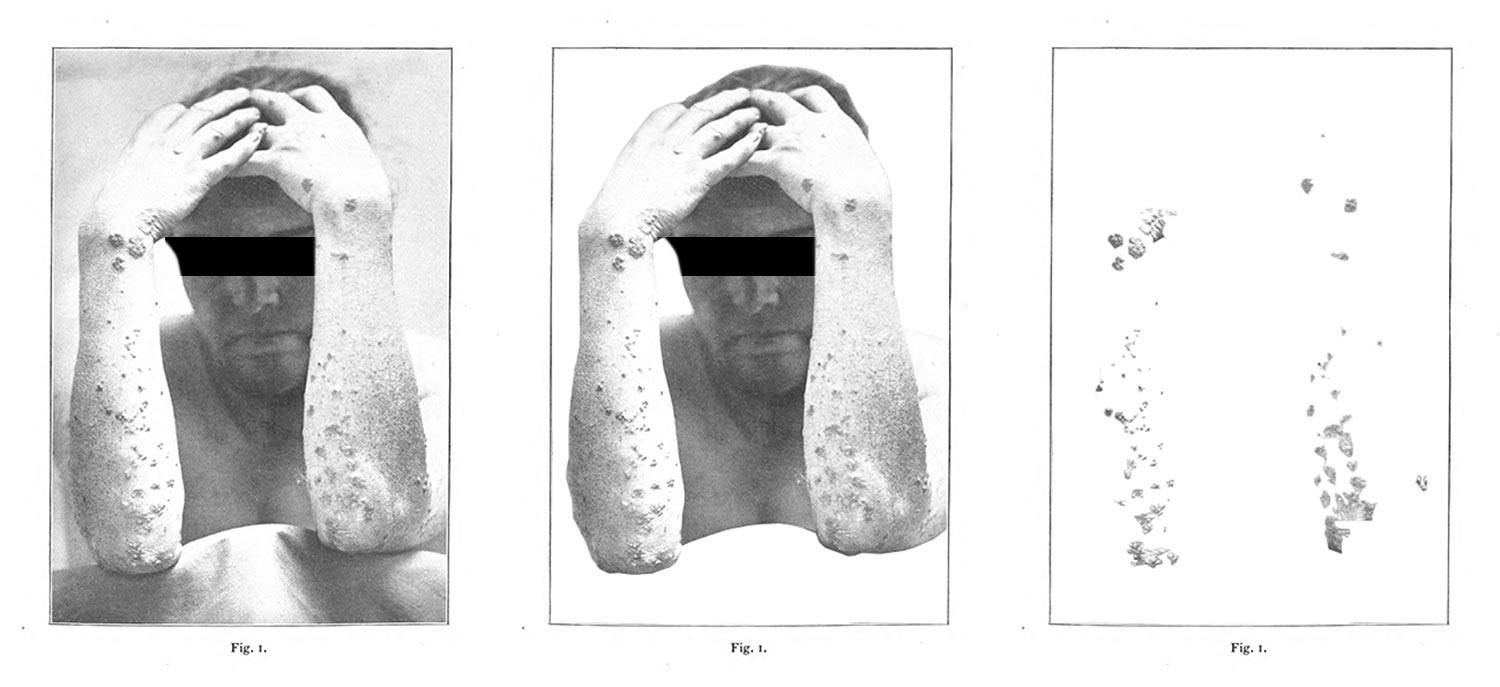

The mouseover functionality called attention to the presence of the doctor, scientist, assistant, or other discursive element that kept a patient sitting (fig. 1), and the on-click functionality helped distill the otherwise abstract aspect of the disease itself (fig. 2) (3.3.2). Beginning with this work, and building into the dissertation proper, opacity functioned in a dualistic sense: it removed information, but in the process enabled new arguments to be made. It also saw an ethics of refusal (5.2.3)3 as a starting point, which did not negate or obliterate the original material, so much as produce a different relationship between the researcher and their object (0.1.5; 2.4.1; 2.4.3).

-

I did the same kind of approach to images for this dissertation. During the creation of the image dataset (X.1.3), I will flag specific images as selects (which is both marked on the file and in the dataset itself), so I will have a smaller collection of images to look through to find examples. ↩

-

Curtis, Scott. The Shape of Spectatorship: Art, Science, and Early Cinema in Germany. New York: Columbia University Press, 2015. 37-44. ↩

-

Refusal is a central term for the next chapter. See: Grande, Sandy. “Refusing the University.” In Describing Diverse Dreams of Justice in Education, edited by Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Wang, 47–65. London: Routledge, 2018; Tuck, Eve, and K. Wayne Yang. “Unbecoming Claims: Pedagogies of Refusal in Qualitative Research.” Qualitative Inquiry 20, no. 6 (2014): 811–18; Simpson, Audra. “On Ethnographic Refusal: Indigeneity, ‘Voice’ and Colonial Citizenship.” Junctures 9 (2007): 67–80; Liboiron, Max. Pollution Is Colonialism. Durham & London: Duke University Press, 2021. ↩