Introduction

Specimen Studies

0.1.1 | 0.1.2 | 0.1.3 | 0.1.4 | 0.1.5Methods

0.2.1 | 0.2.2The Structure of this Dissertation

0.3.1Tuberculosis' Visual Culture

Visual Practices in Medical Culture

1.1.1 | 1.1.2 | 1.1.3Seeing and Settling in the Sanatorium Movement

1.2.1 | 1.2.2 | 1.2.3 | 1.2.4 | 1.2.5Teaching Public Health

1.3.1 | 1.3.2 | 1.3.3 | 1.3.4 | 1.3.5Representing Doctors in Tuberculous Contexts

1.4.1 | 1.4.2Using Human Specimens in the Study of Tuberculosis

Seeing Disease in Methyl Violet

2.1.1 | 2.1.2 | 2.1.3 | 2.1.4Case Histories

2.2.1 | 2.2.2 | 2.2.3 | 2.2.4Visceral Processes

2.3.1 | 2.3.2Relation

2.4.1 | 2.4.2 | 2.4.3Arts-Based Inquiry

Introduction

3.1.1 | 3.1.2 | 3.1.3 | 3.1.4Terminal Imaginaries & Tuberculous Imaginaries

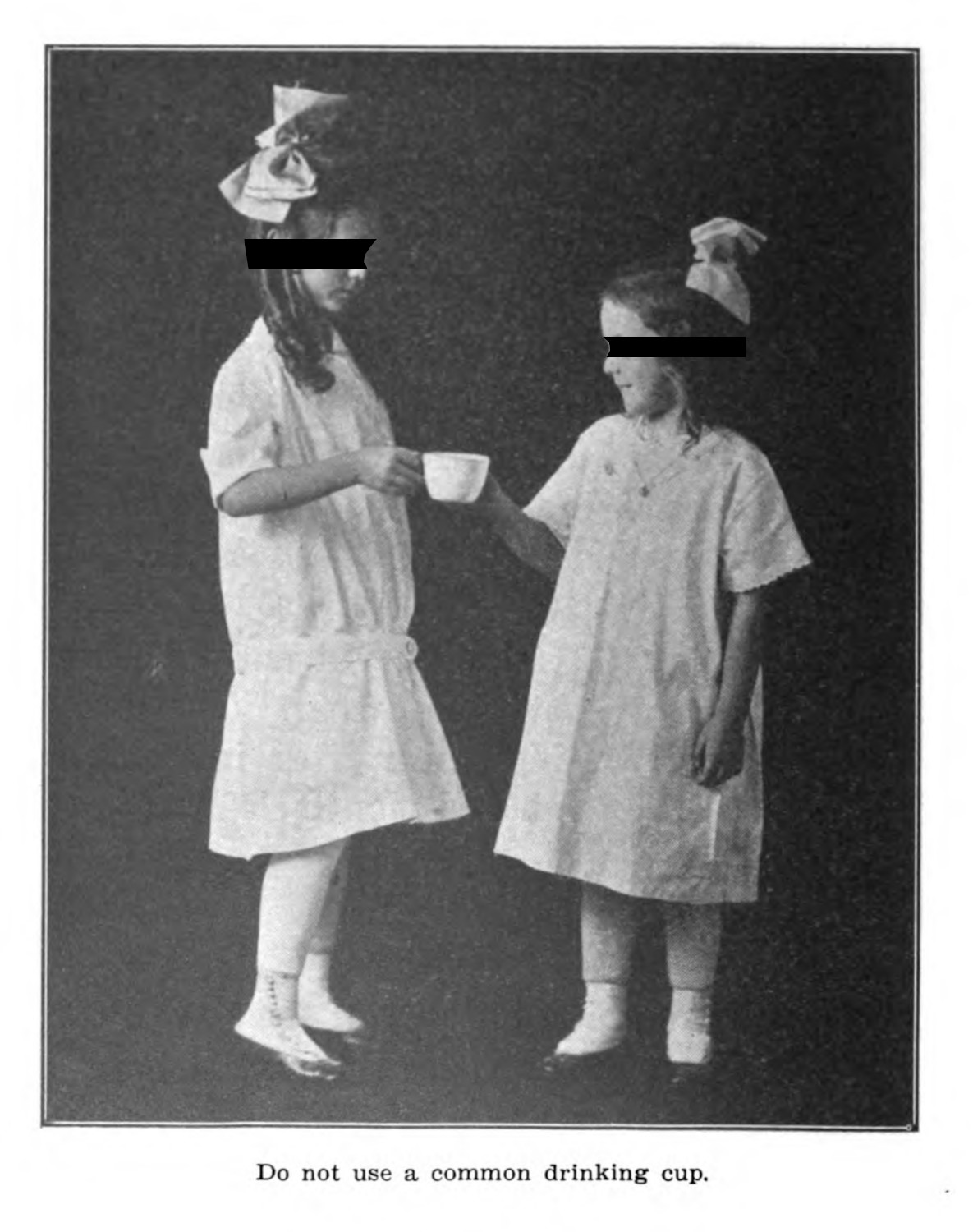

3.2.1 | 3.2.2 | 3.2.3 | 3.2.4 | 3.2.5 | 3.2.6Dermographic Opacities

3.3.1 | 3.3.2 | 3.3.3 | 3.3.4Tactical Pretensions

3.4.1 | 3.4.2 | 3.4.3Designing Opacity

A Shift towards the Anticolonial

4.1.1 | 4.1.2 | 4.1.3 | 4.1.4Refusals and Opacities

4.2.1 | 4.2.2 | 4.2.3 | 4.2.4Digital and Ethical Workflows

4.3.1 | 4.3.2 | 4.3.3 | 4.3.4 | 4.3.5Conclusion

4.4.1Coda

Prometheus Undone

5.1.1 | 5.1.2 | 5.1.3 | 5.1.4Appendix

The Tuberculosis Corpus

X.1.1 | X.1.2 | X.1.3Web Design

X.2.1 | X.2.2 | X.2.3 | X.2.4Installation Materials

X.3.1 | X.3.2 | X.3.3Index

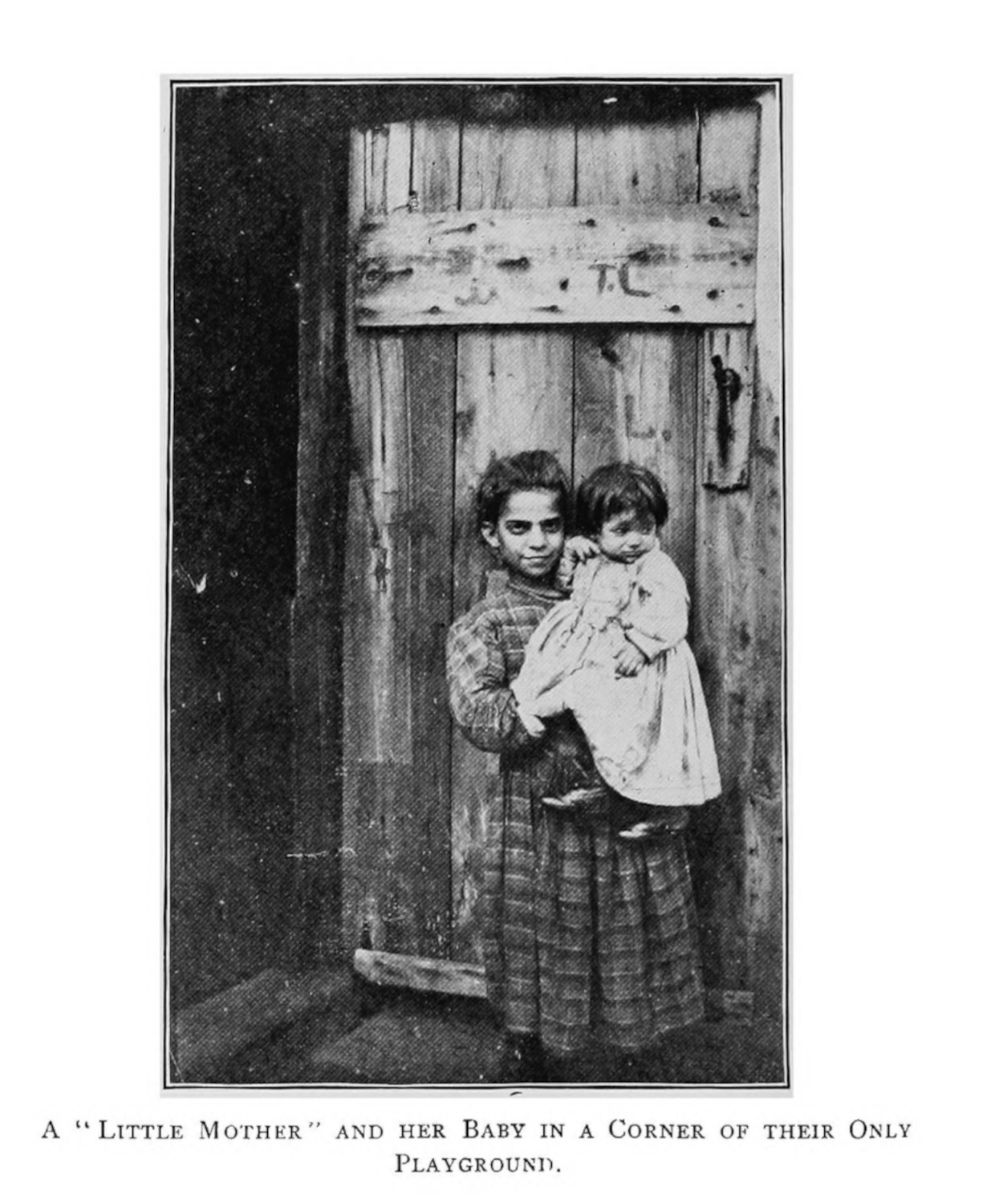

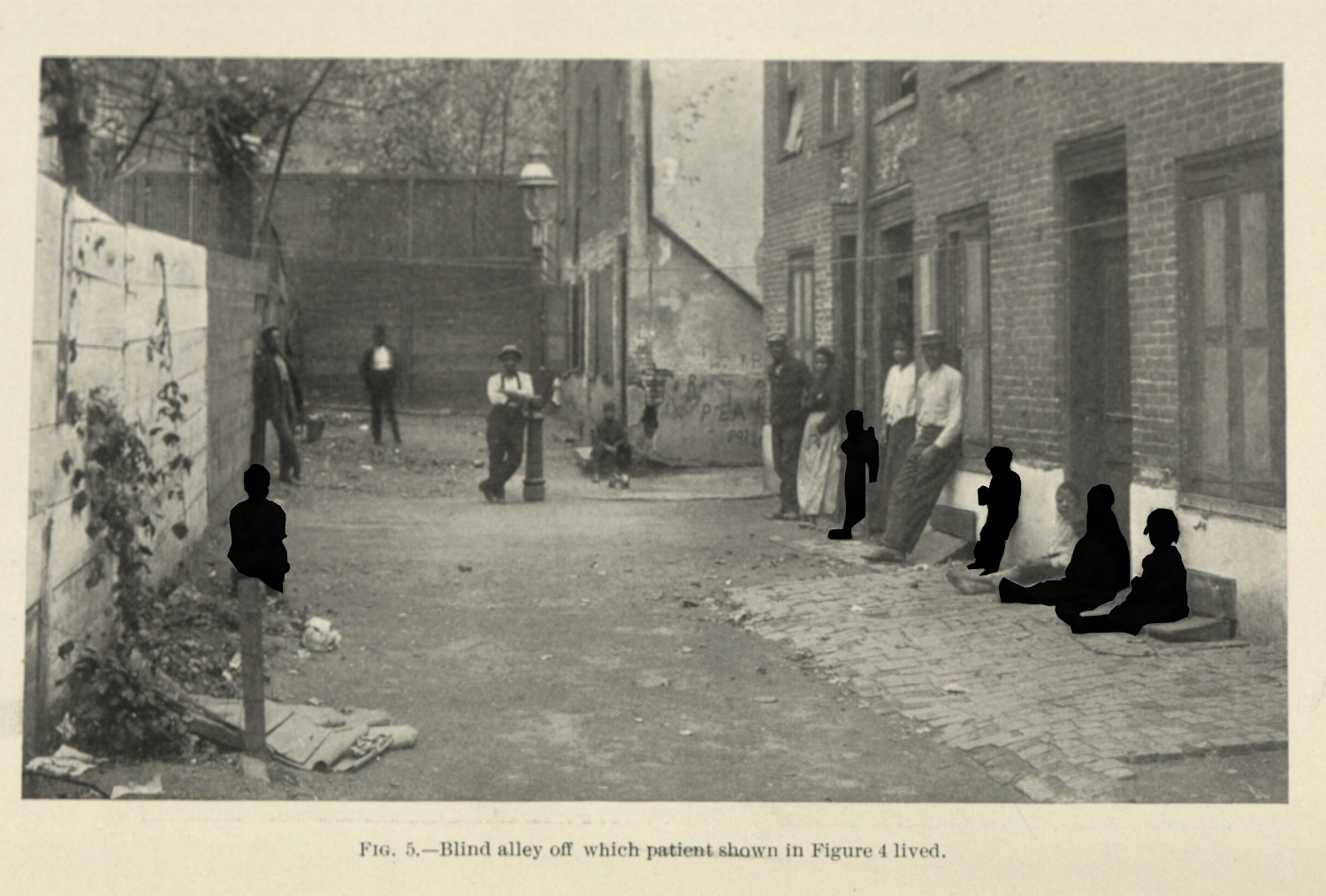

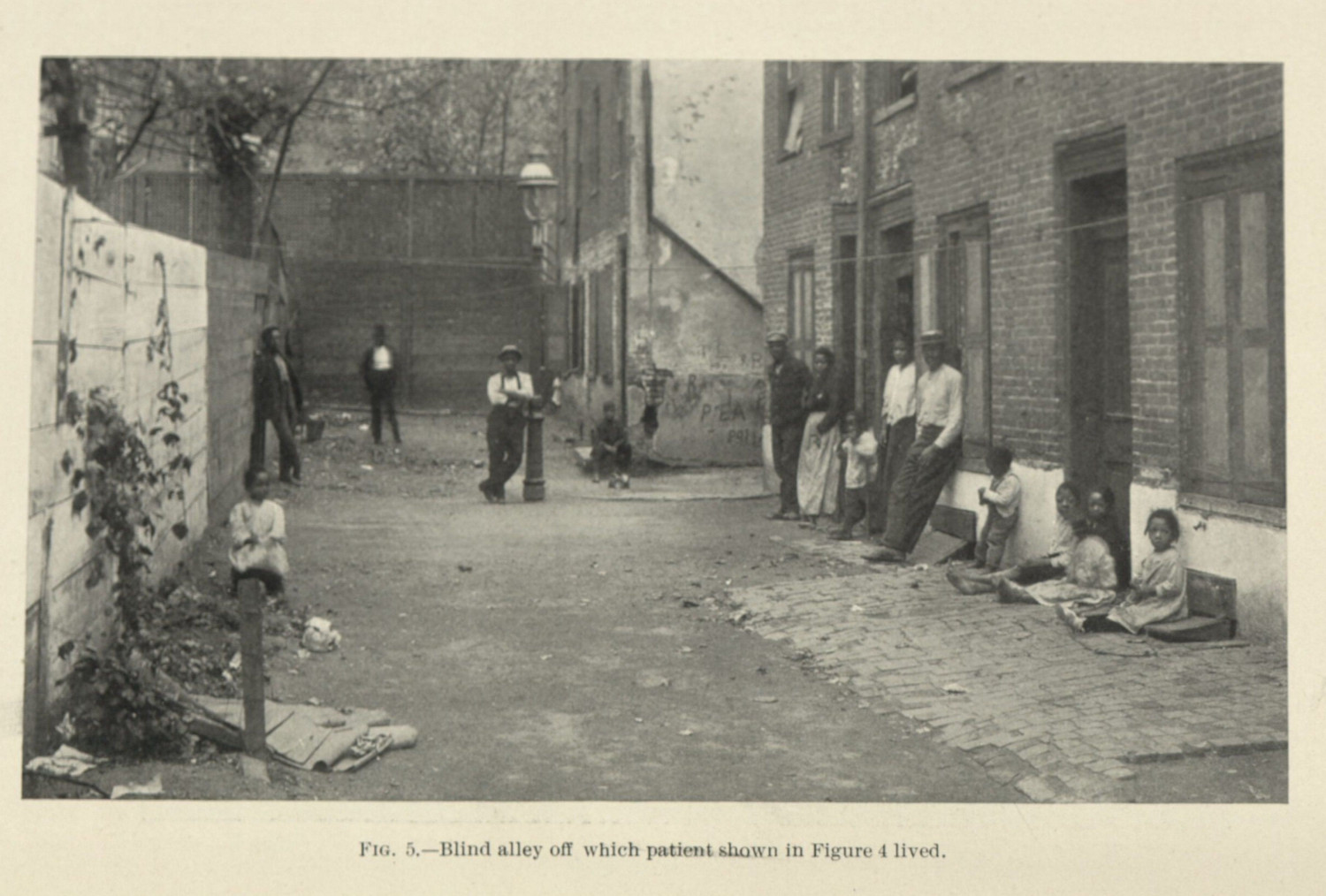

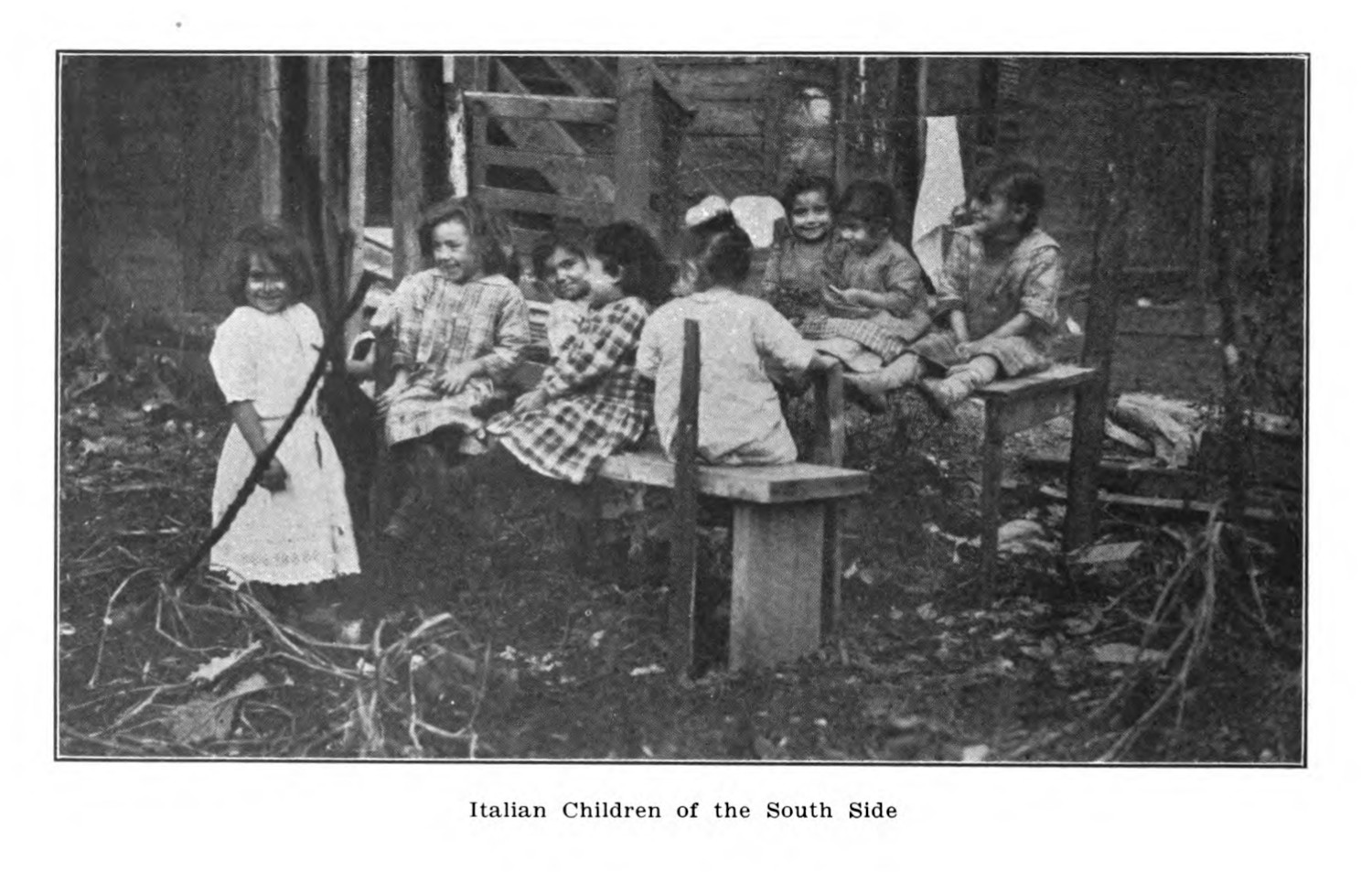

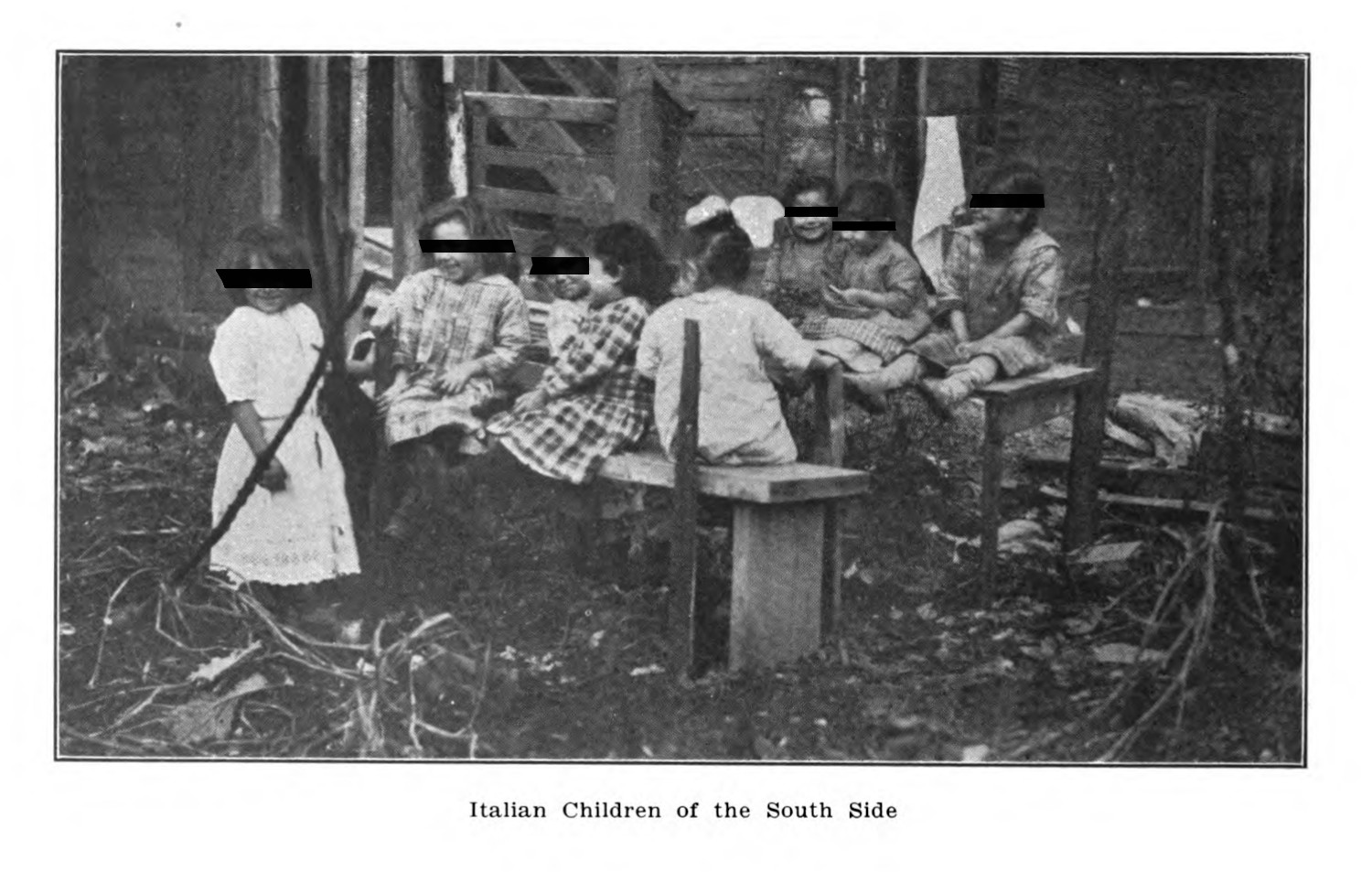

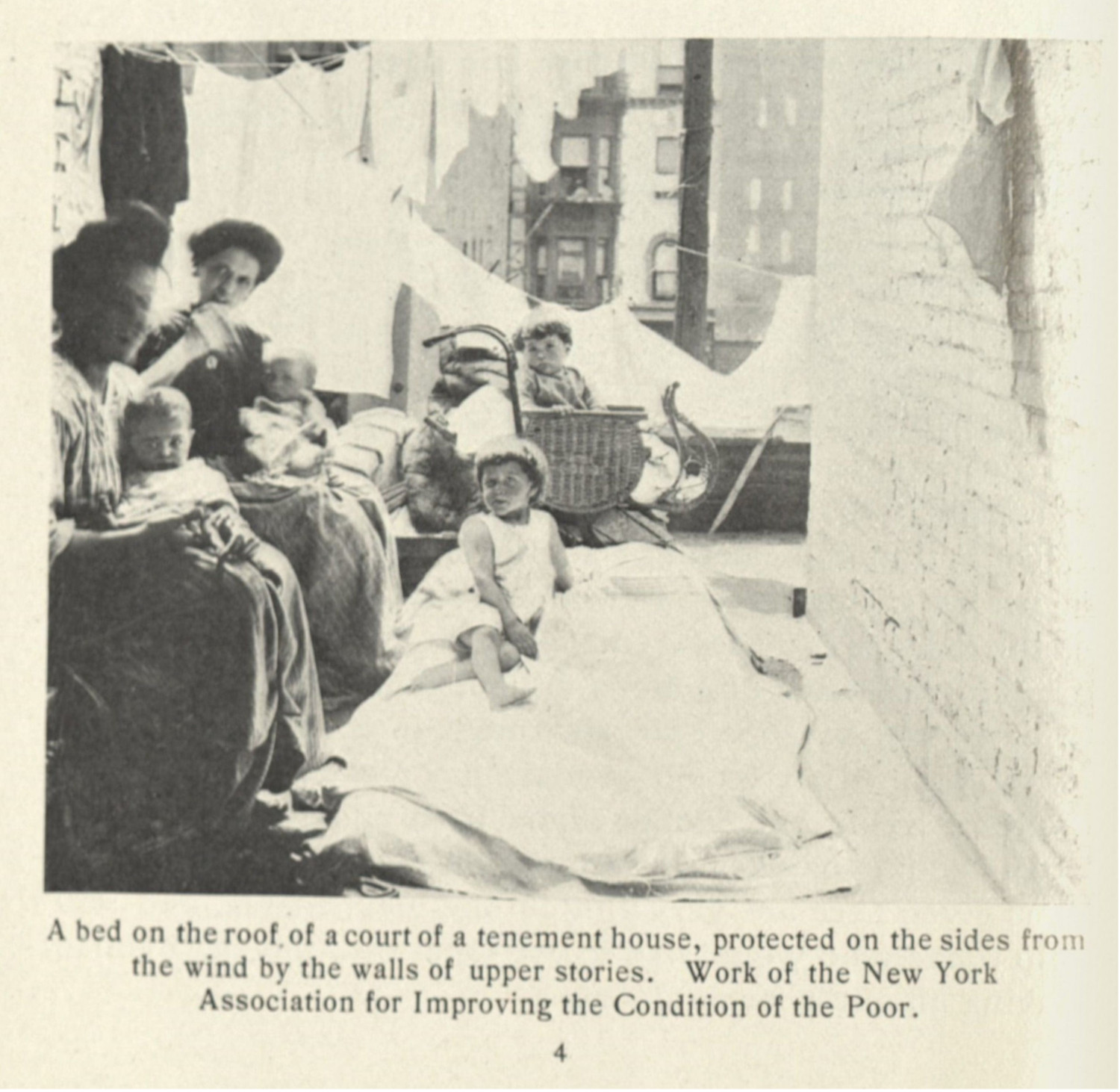

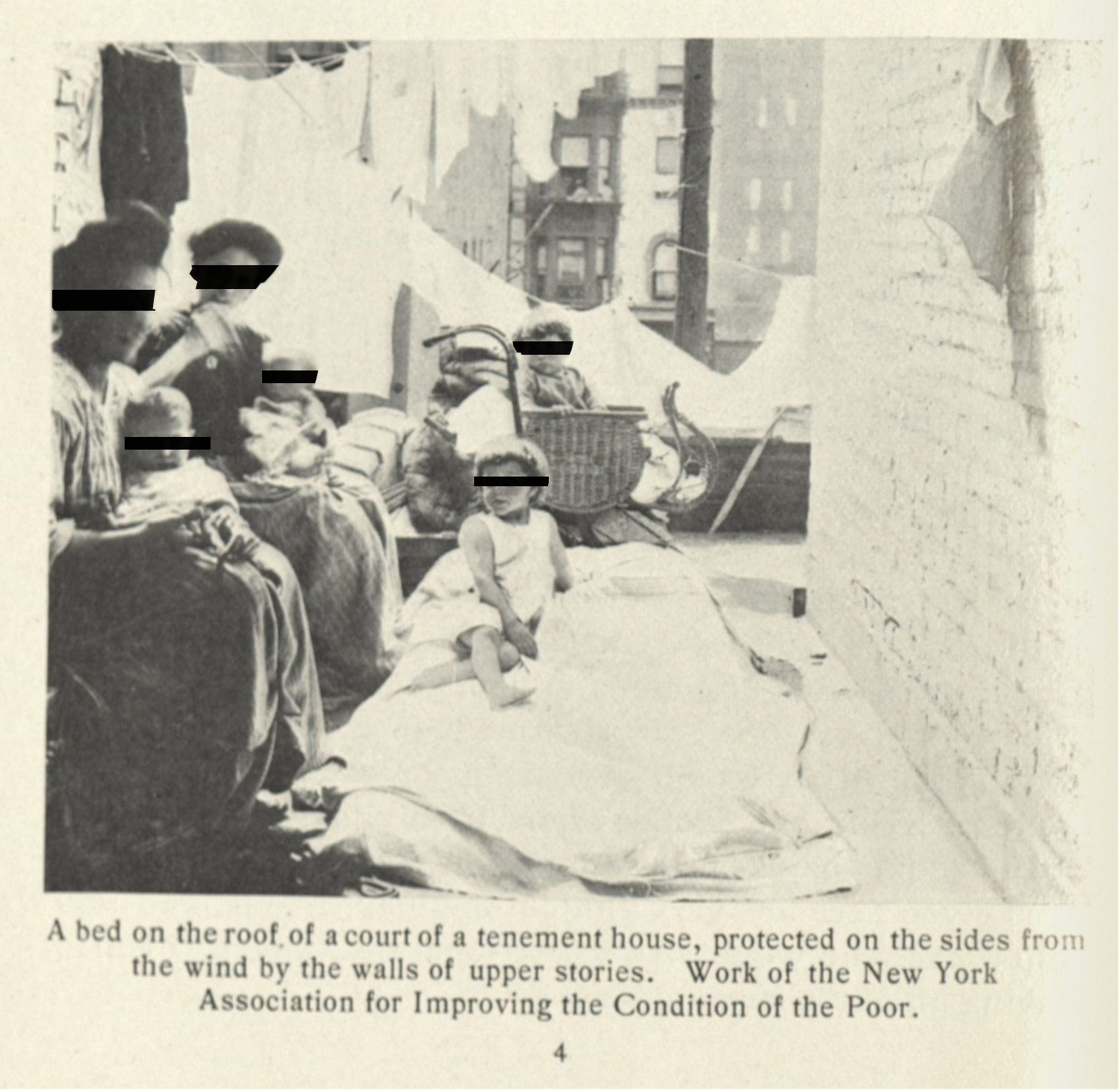

Discussions of urban public health often included handwringing regarding the health of children, noting the lack of space for play (figs. 1 - 3). The focus on children was partly associated with assumptions regarding initial infection: patients with tuberculosis were thought to get sick early in life, with have the disease lay dormant in their bodies into adulthood (2.3.1). Protecting a generation in their youth was thought to protect them in their adult lives as well.

These images were meant, in many cases, to prove the value of public health intervention: to let nurses come into these supposedly squalid spaces and fix them. These images imply an urgent need, and they centralize a logic that those who live in these spaces were ignorant of their hygienic dangers. The focus on children was especially important for public health nurses, who would visit schools and domiciles to educate the young and their families on the proper ways to reduce disease transmission. These nurses served as a bridge between the private household and public school and were linked to both the popularization of nursing as well as the home economics movement.1 This linkage, however, was counterproductive as interventions by public health nurses and other public health officials were often not welcomed. As Peter Ward describes,

The poor often resented public intrusions into their private lives and the violation was all the more offensive if it came from their social superiors. In working-class circles particularly, inspections roused the shame of being singled out for lapses in personal hygiene. The resulting stigma touched school-children as well as their parents, particularly their mothers, whose struggles to keep their offspring clean were closely tied to their family’s strivings for respectability.2

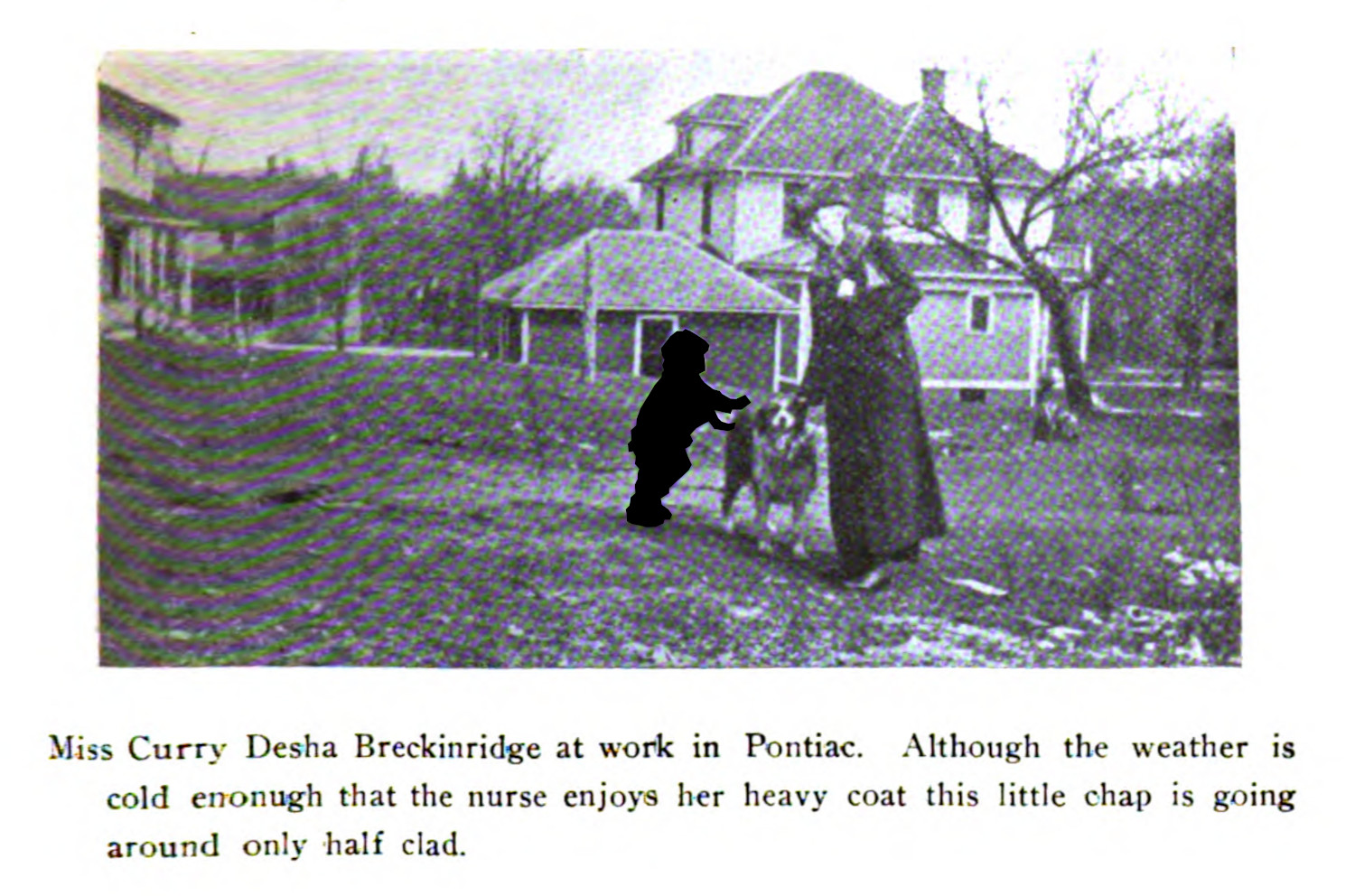

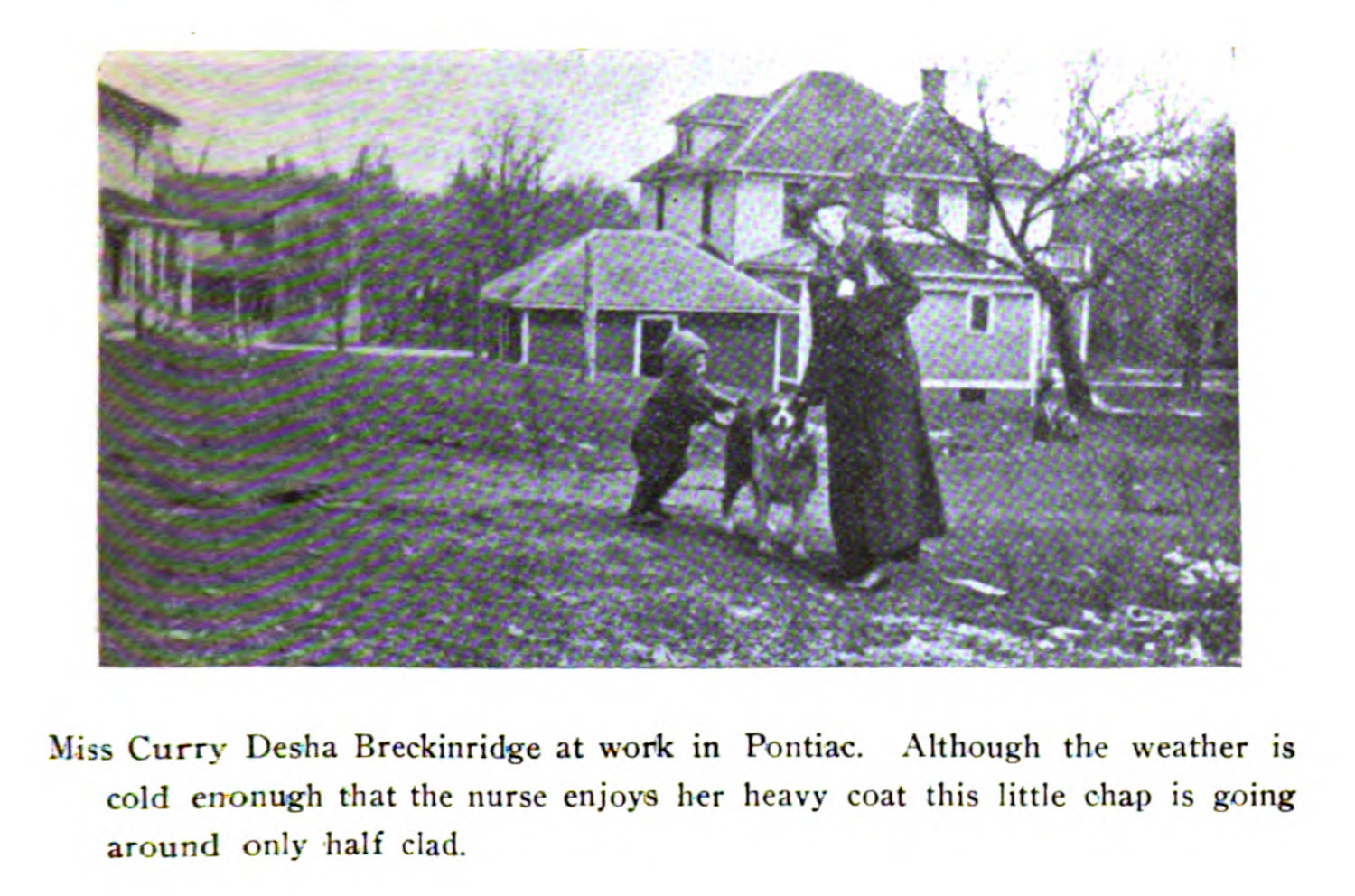

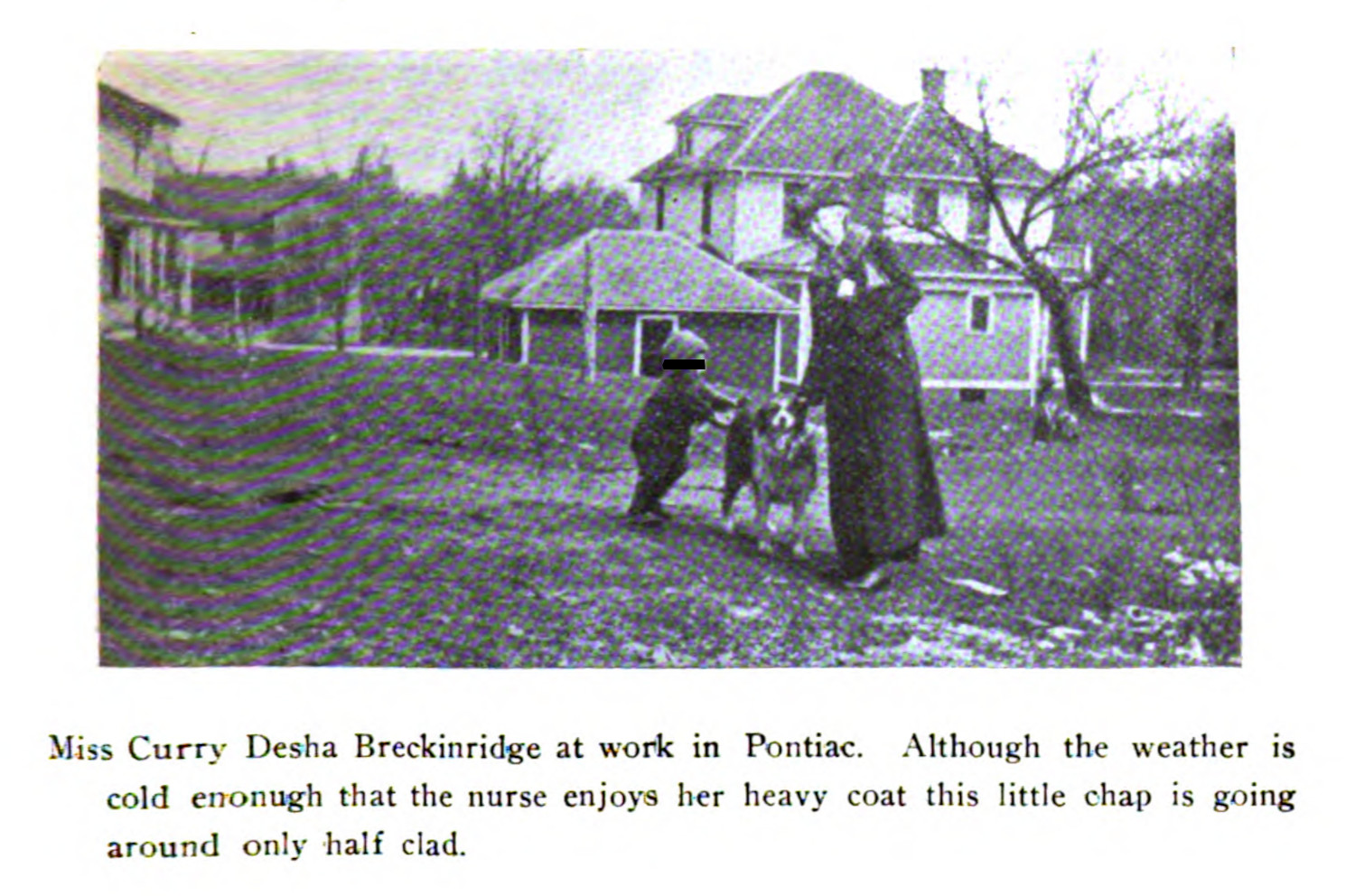

The Bulletin of the Michigan Association for the Prevention and Relief of Tuberculosis ran a series of diary-like entries written by a practicing public health nurse—Curry Desha Breckinridge (fig. 4). She travelled from town to town in Michigan speaking with local officials, examining the town’s public spaces—like the local theatres—as well as making trips to examine the homes of sick children. Central to this work was the teaching of proper hygiene, which was especially important for those who had been diagnosed with tuberculosis.

In one of her extended reports, she included the writing of a thirteen year old consumptive, summarizing the disease and how patients should maintain themselves while sick:

The following composition, written by a 13 year old Polish lad who was suffering from tuberculosis, gives an idea of how the boy had been taught to care for himself:

“Consumption is a bad sickness. Every time the clock strikes one someone dies of consumption in Illinois, 1 every hour, 24 every day, 750 every month, 9000 every year. If a person wants to be not sick, he most do what the doctor tells him. Person (sic) who has consumption most (sic) sleep by an open window and in the morning you most splish on your chest with cold water and be on open air as much as a person have time and at least have your full quart of milk every day and drink eggs and drink his medicine regular and have many exercise. If a person don’t do what the doctor tells him he can’t be healthy. If a person is sick on consumption that person he most (sic) watch himself because if he cough he most (sic) hold a paper by his mouth and after while the person most burn the paper. He most (sic) have different clothes and change them in the morning.”3

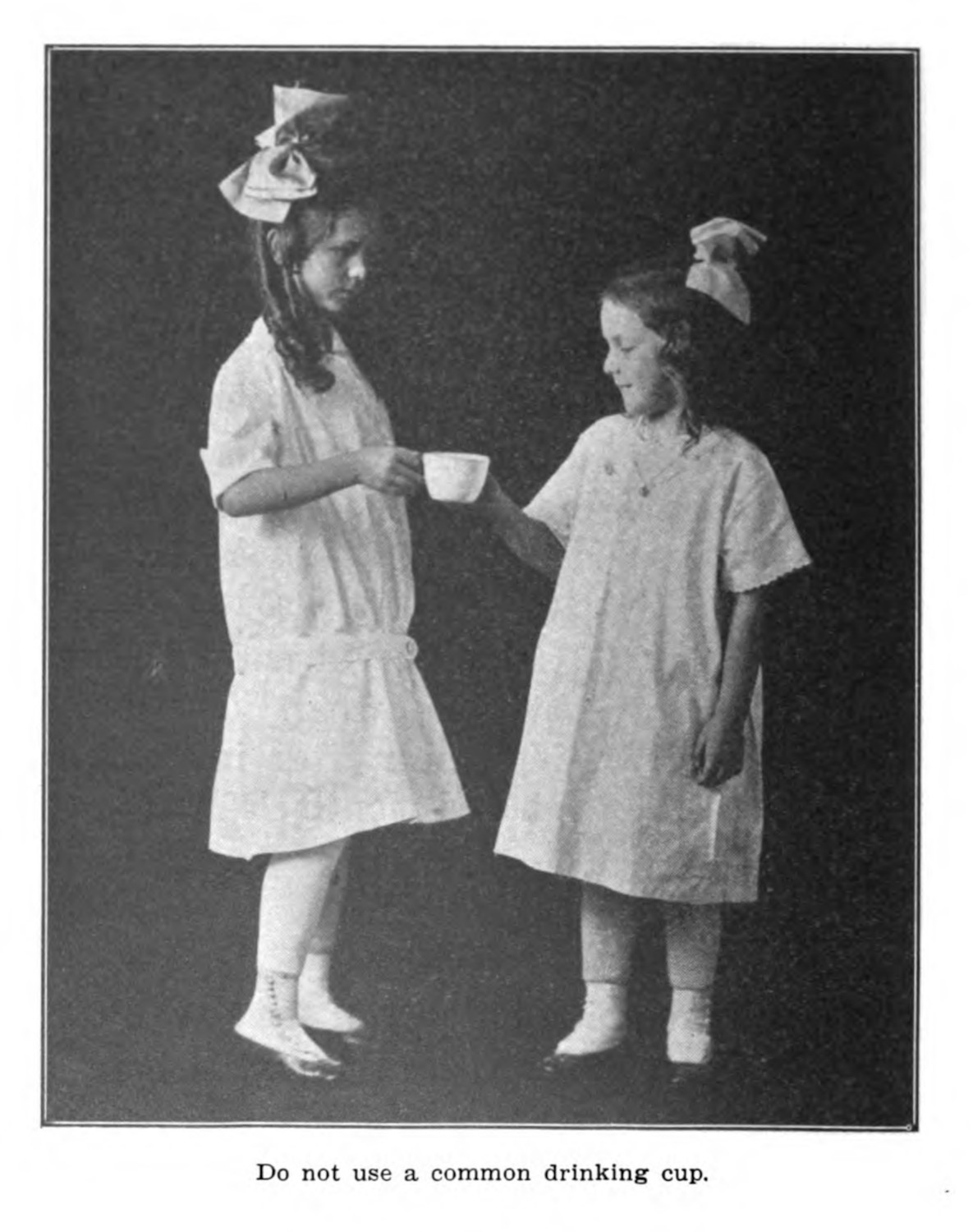

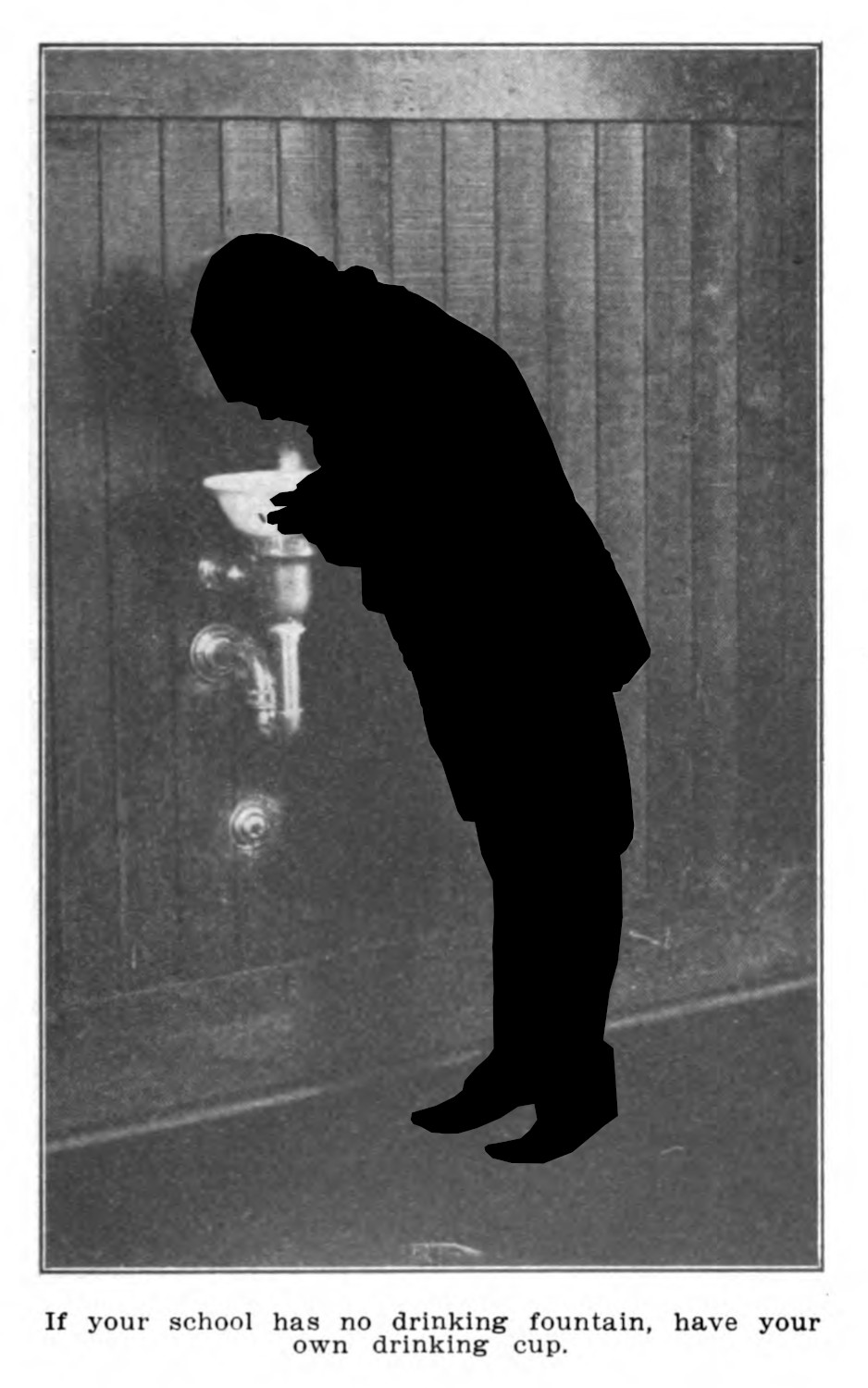

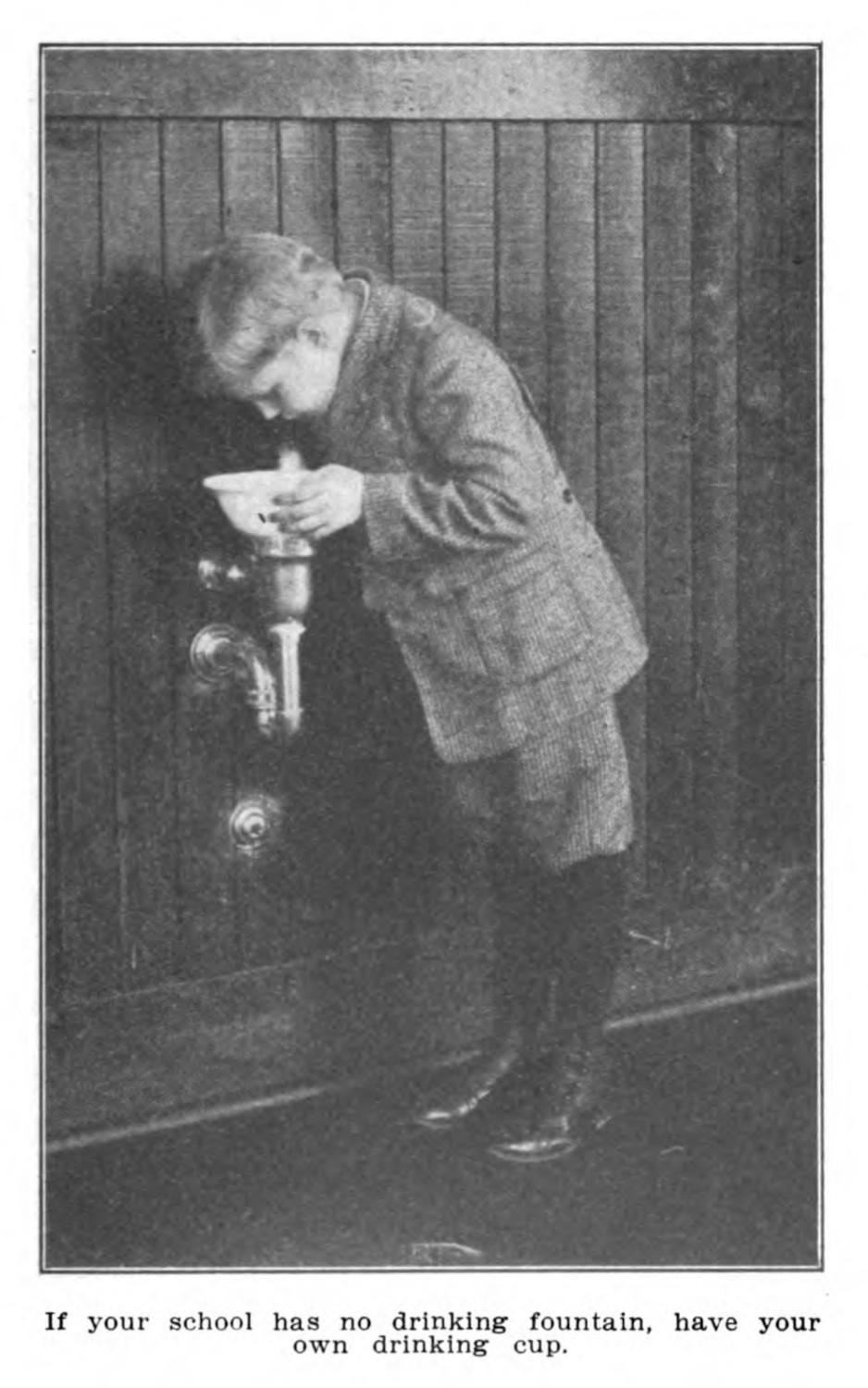

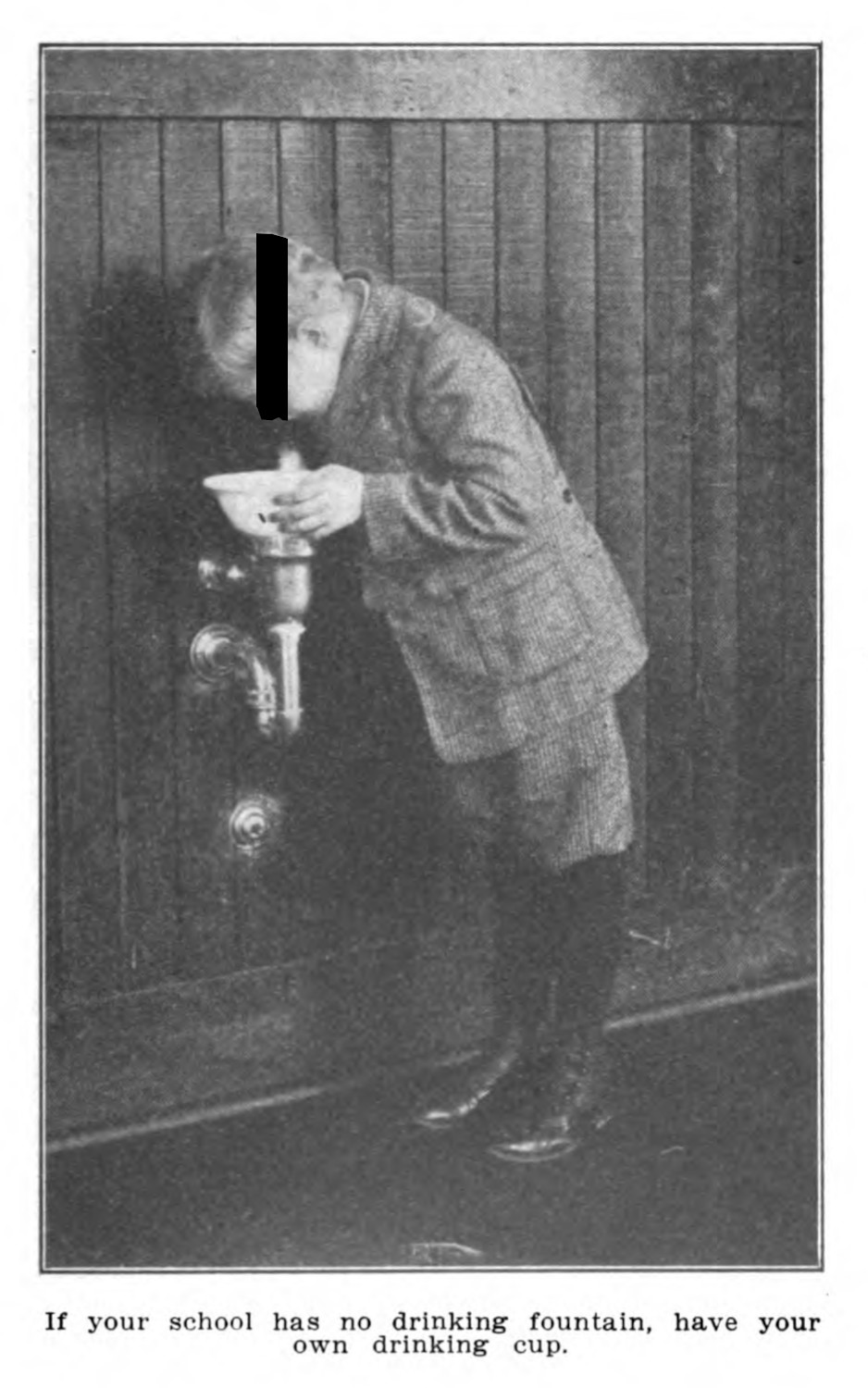

Breckinridge’s work, like other health nurses, was to educate children and families in the kinds of knowledge around tuberculosis that were understood and accepted (figs. 5 & 6). Other institutions like public and charity sanatoria, dispensaries, and hospitals pushed these rhetorics as well, seeing the education of sick patients as a necessary intervention against the spreading of the disease.

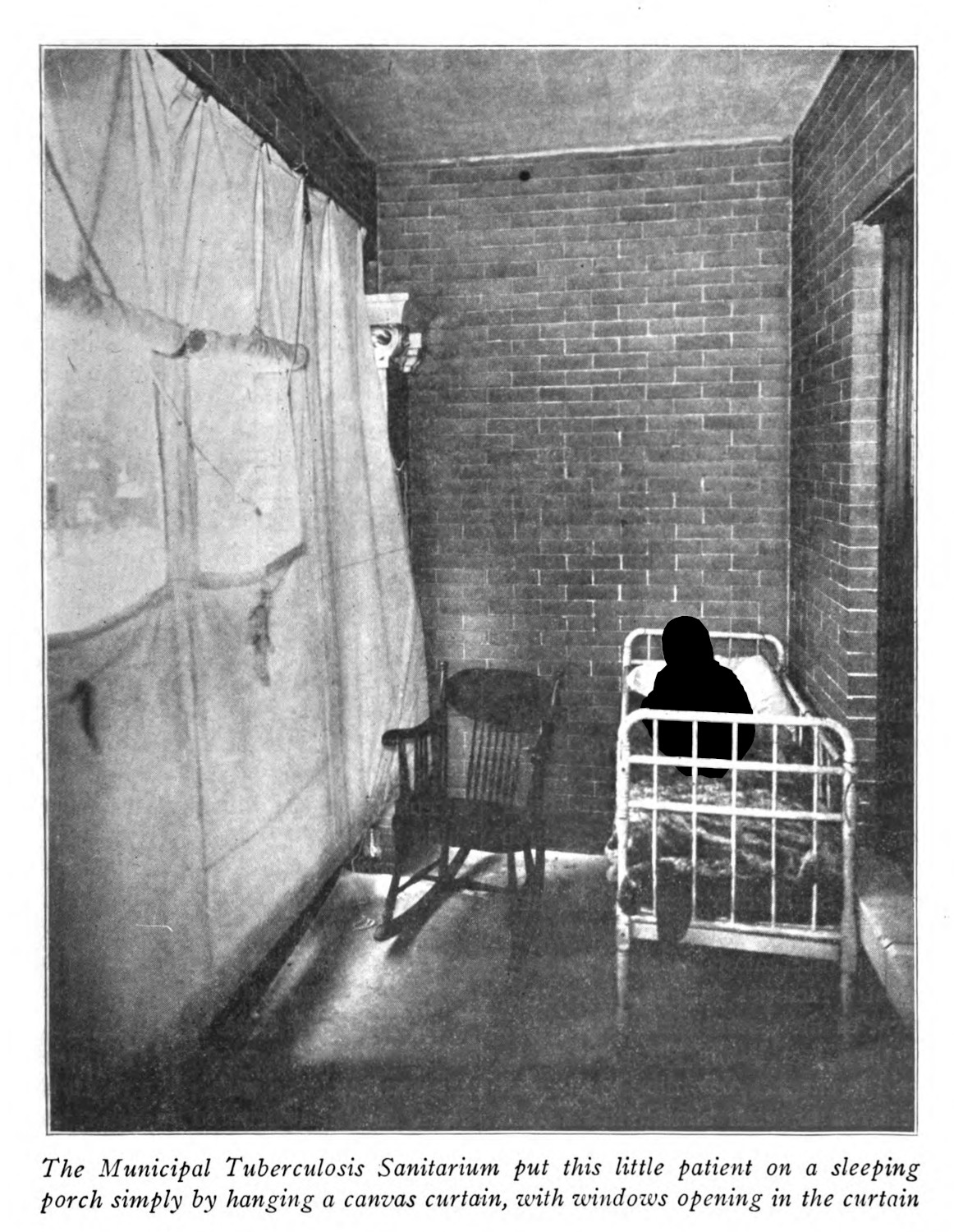

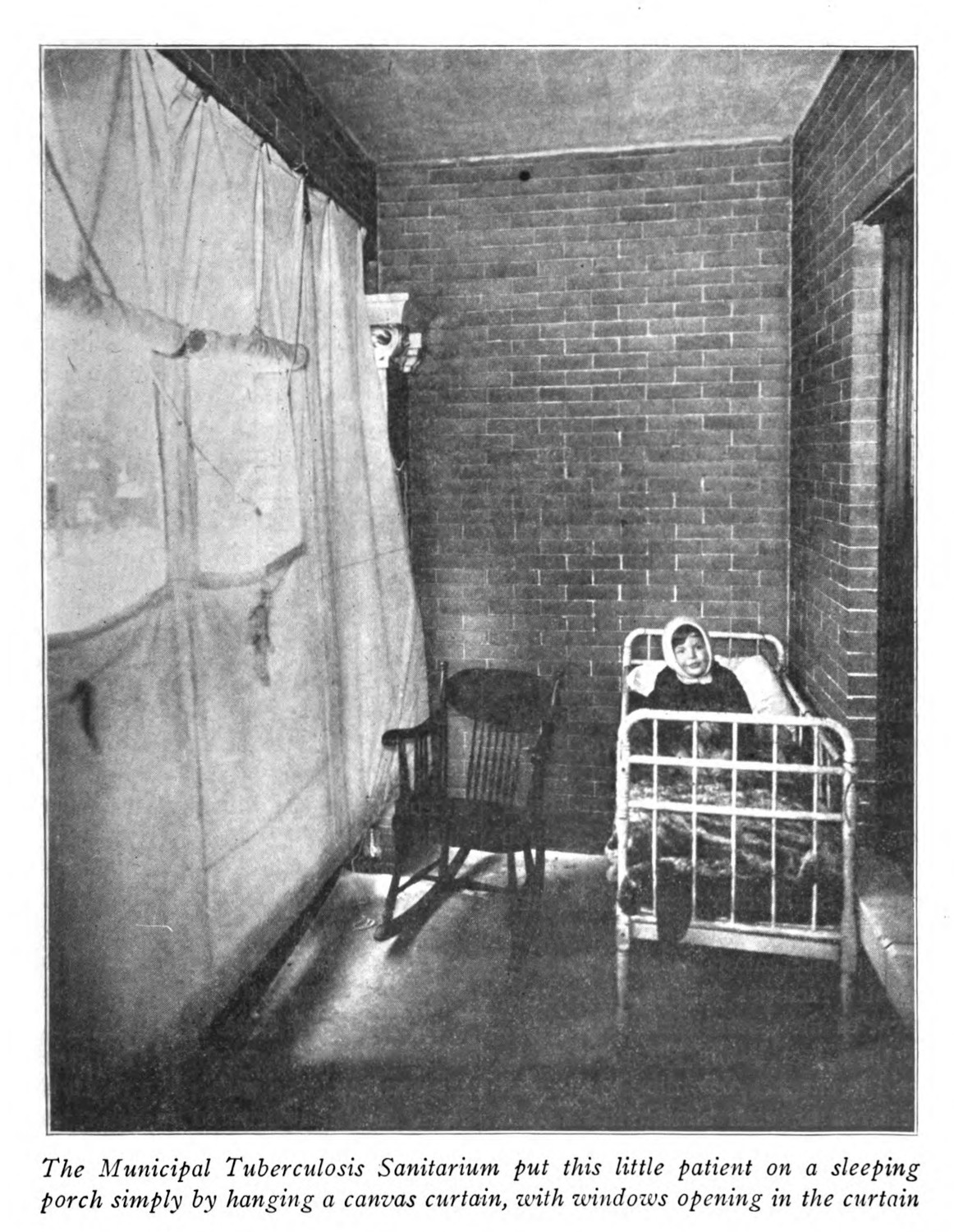

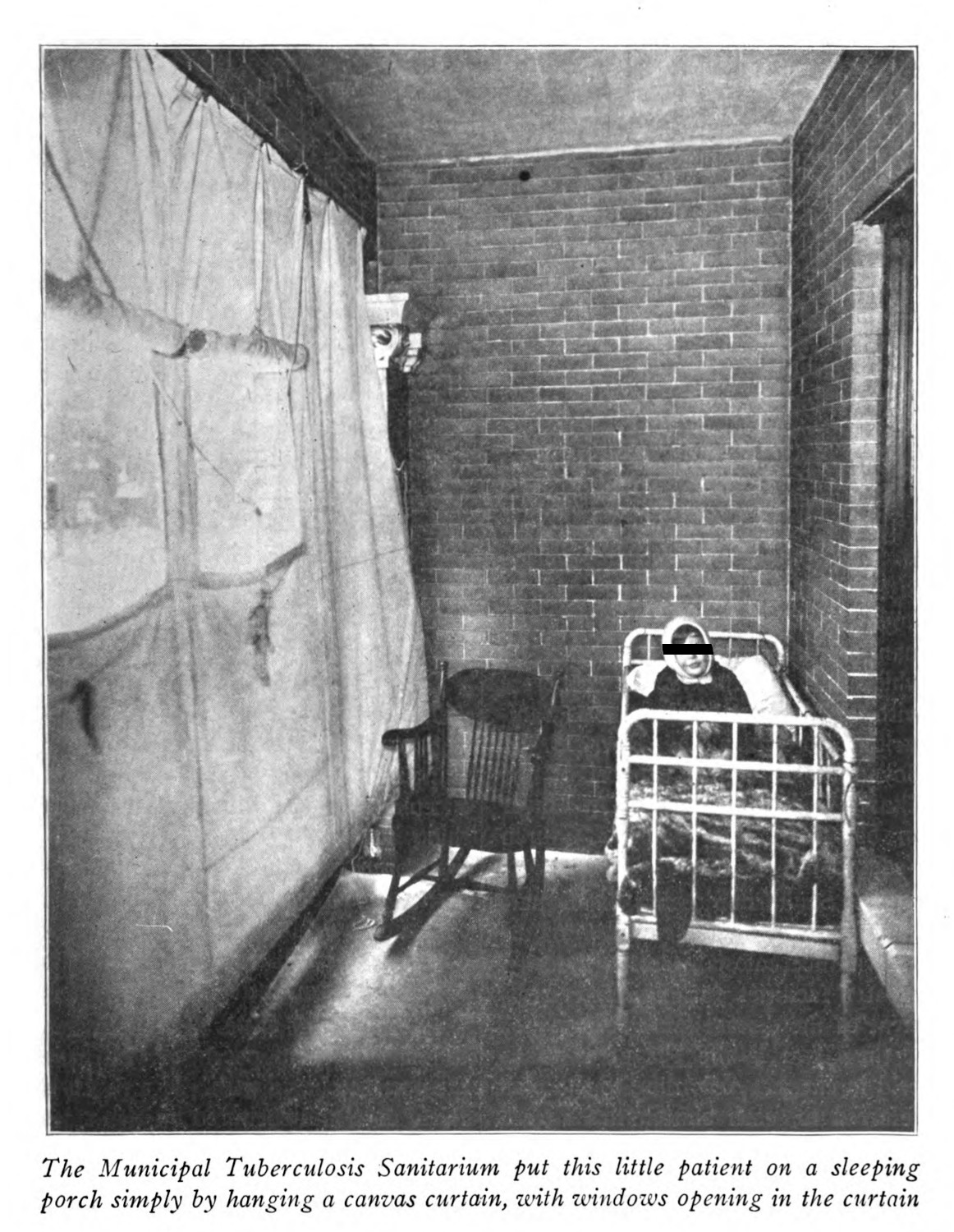

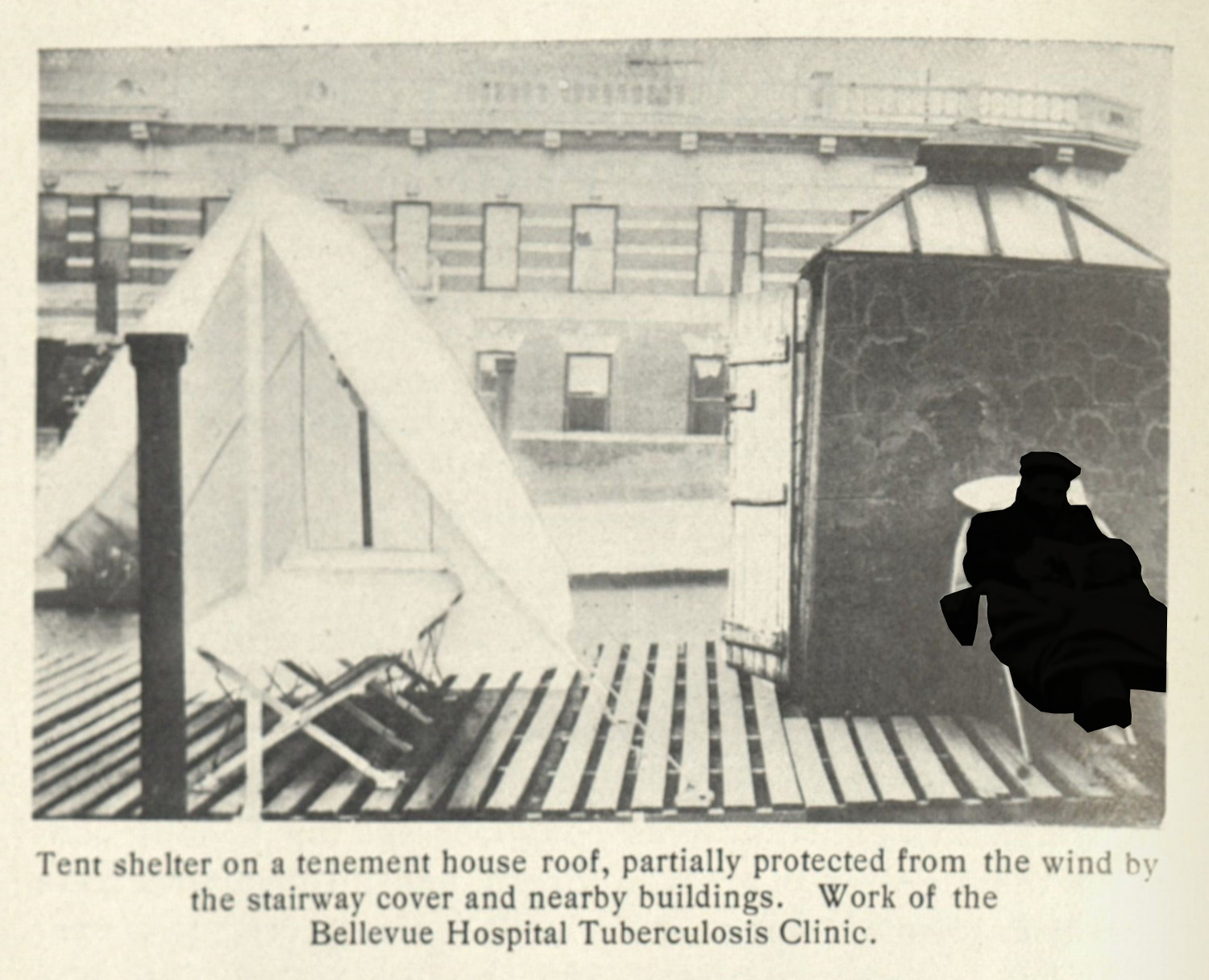

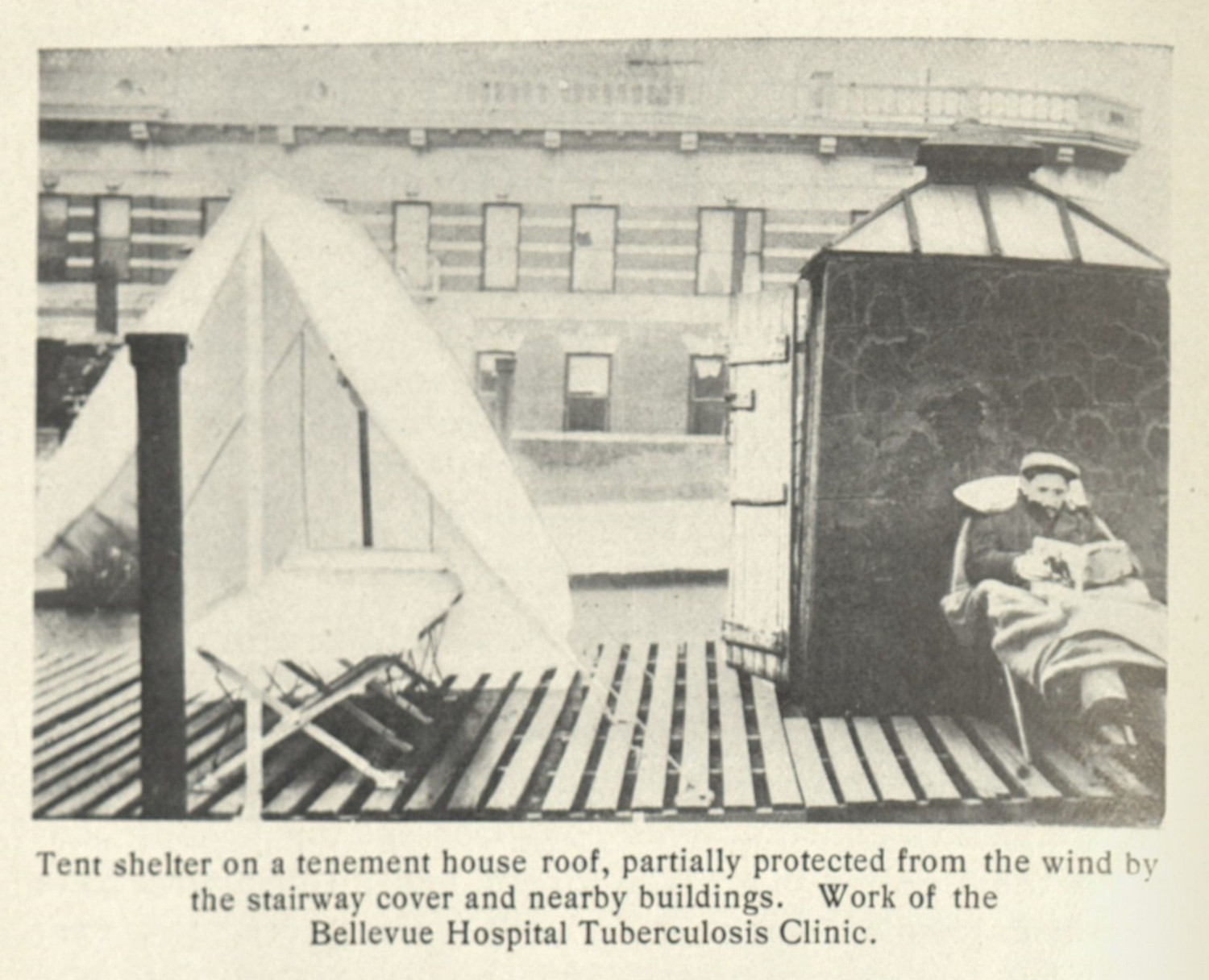

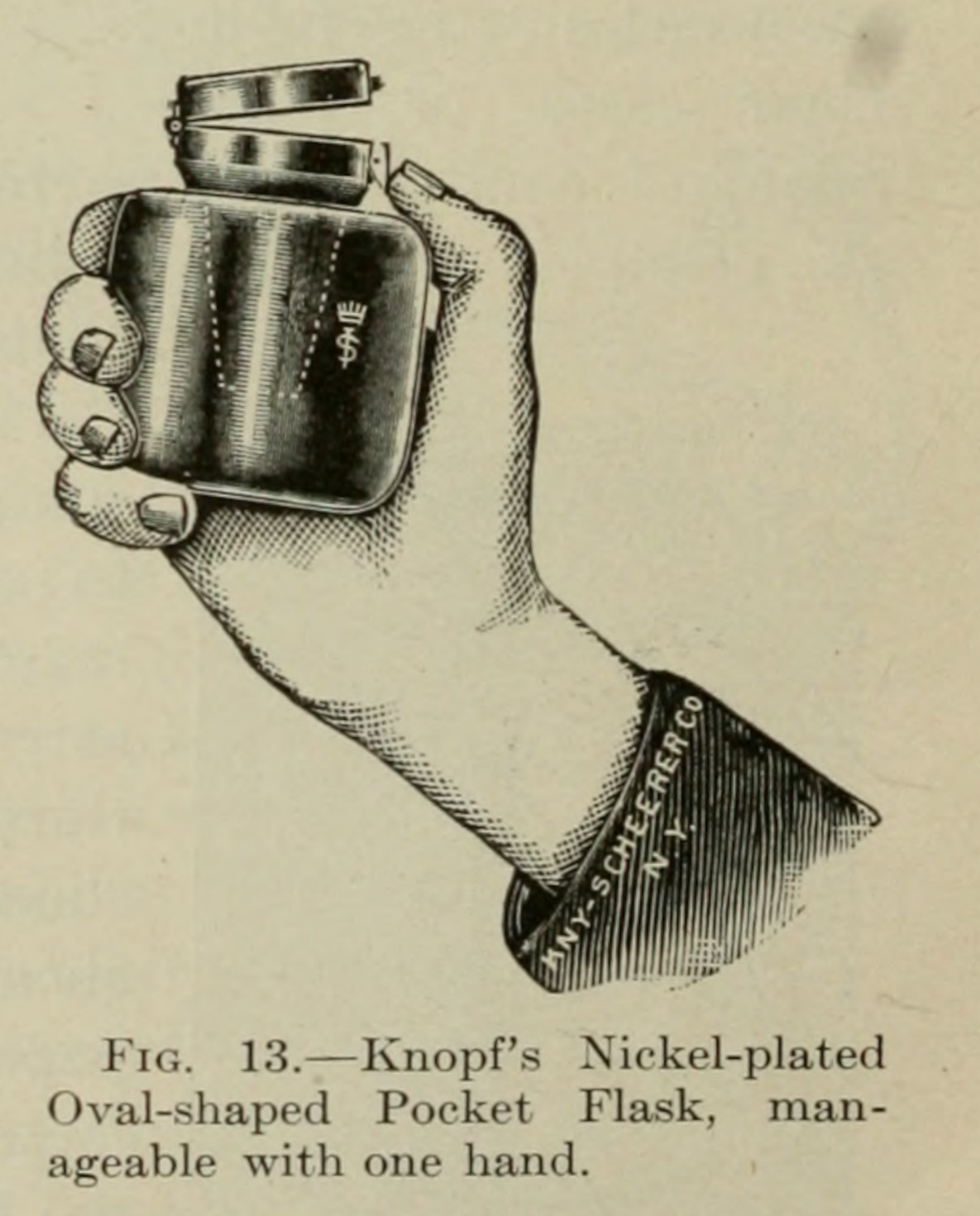

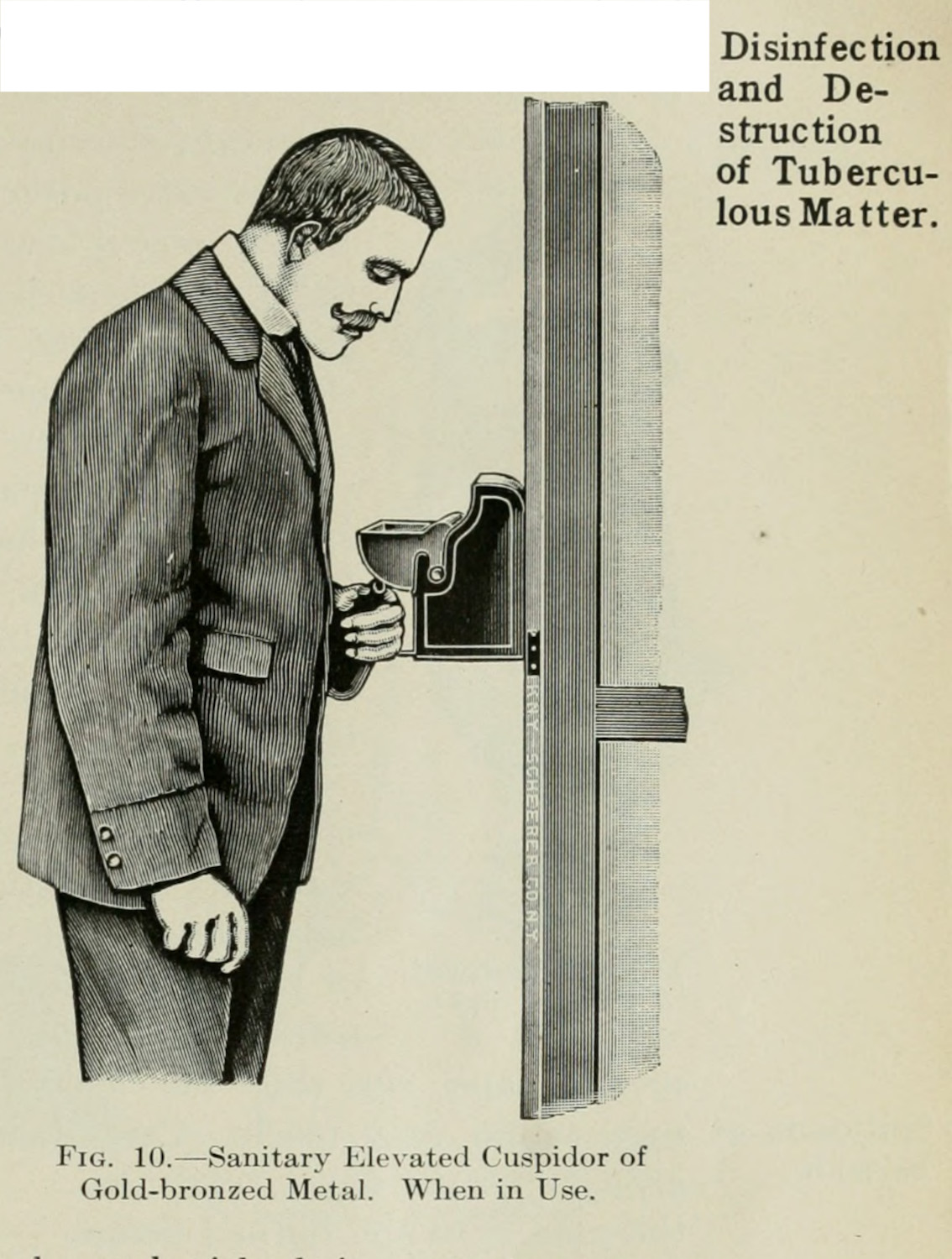

The prose borrowed by Breckinridge summarizes the personal expectations that were placed on patients with tuberculosis. To be good in this framework involved a great deal of work. For patients living in cities, they had to travel to day camps, or their families would have to rearrange their entire living space (figs. 7 - 9). Patients would have to monitor their expectoration, contain it in a sealed container, and disinfect it afterwards (figs. 10 & 11). The onus was on the patients themselves: they would have to change their habits, their ways of interacting with others, and their environments to fit externally imposed hygienic standards.4

In charity sanatoria, hygiene structured many of the rules that patients were required to follow. In charity organizations, like at Lawrence F. Flick’s New Haven Sanitarium, the institution’s expectations made it untenable for patients to stay for a long period. As Barbara Bates describes,

Fundamental to life at a sanatorium was discipline. Patients had to comply with the medical regimen in order to get better, physicians believed; they had to take special precautions to prevent the spread of infection; and they had to adapt to living in a group, cooperating with others as needed, and if they were well enough, sharing the work.5

In the sanatorium’s early years managing patients proved to be quite difficult; the institution’s expectations for patients included labor for the sanatorium in addition to prescriptions of exposure to open air (1.2.2). Patients were often unwilling to put up with either expectation. Beyond problems caused by rowdy patients, and disagreements by managing doctors and nurses, New Haven’s poorly heated barn and the expectations of the open-air treatment caused issues during winter. Bates summarizes this complaint through letters by Elwell Stockdale to Flick:

As to charges of cruelty, if making the men ‘stick to their cure is cruel I plead guilty. They—some of them—feel quite abused at time (I hear) that I wont (sic) permit them to bum around the kitchen fire and in the house or barn.’ The men were supposed to stay outside; his best cases stayed until bedtime. ‘[I] can honestly say that with all the money I spent for my cure, I never had any comfort more than these men.”6

I look to this example to describe how expectations were projected onto patients, and how medical-practitioner expertise became a way to reinforce these guidelines. Becoming a perfect patient, one who rests when told, works when told, protects others from their infection, and stays within the strict regimens outlined by professionals required a great deal of work. The ideal patient, the properly hygienic patient, was one who could conform to sanatorium life, who would not quarrel with others, and whose disease was sufficiently treatable. Falling out of this ideal made the patient into something that was not just injurious to themselves, but to the broader fabric of society.

-

Ward, Peter. The Clean Body: A Modern History. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2019. 140-141. ↩

-

Ward, Peter. The Clean Body: A Modern History. 148. ↩

-

Curry Desha Brekinridge. “June work of Visiting Nurse Miss Curry Desha Breckinridge” Bulletin of the Michigan Association for the Prevention and Relief of Tuberculosis 3. 1914. ↩

-

There is a partial connection to notions of the social model of disability. Shakespeare, Tom. “The Social Model of Disability.” In The Disability Studies Reader, 214–21. New York & London: Routledge, 2006. ↩

-

Bates, Barbara. Bargaining for Life: A Social History of Tuberculosis, 1876-1938. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1992. 84. ↩

-

Ibid., 82. ↩