Introduction

Specimen Studies

0.1.1 | 0.1.2 | 0.1.3 | 0.1.4 | 0.1.5Methods

0.2.1 | 0.2.2The Structure of this Dissertation

0.3.1Tuberculosis' Visual Culture

Visual Practices in Medical Culture

1.1.1 | 1.1.2 | 1.1.3Seeing and Settling in the Sanatorium Movement

1.2.1 | 1.2.2 | 1.2.3 | 1.2.4 | 1.2.5Teaching Public Health

1.3.1 | 1.3.2 | 1.3.3 | 1.3.4 | 1.3.5Representing Doctors in Tuberculous Contexts

1.4.1 | 1.4.2Using Human Specimens in the Study of Tuberculosis

Seeing Disease in Methyl Violet

2.1.1 | 2.1.2 | 2.1.3 | 2.1.4Case Histories

2.2.1 | 2.2.2 | 2.2.3 | 2.2.4Visceral Processes

2.3.1 | 2.3.2Relation

2.4.1 | 2.4.2 | 2.4.3Arts-Based Inquiry

Introduction

3.1.1 | 3.1.2 | 3.1.3 | 3.1.4Terminal Imaginaries & Tuberculous Imaginaries

3.2.1 | 3.2.2 | 3.2.3 | 3.2.4 | 3.2.5 | 3.2.6Dermographic Opacities

3.3.1 | 3.3.2 | 3.3.3 | 3.3.4Tactical Pretensions

3.4.1 | 3.4.2 | 3.4.3Designing Opacity

A Shift towards the Anticolonial

4.1.1 | 4.1.2 | 4.1.3 | 4.1.4Refusals and Opacities

4.2.1 | 4.2.2 | 4.2.3 | 4.2.4Digital and Ethical Workflows

4.3.1 | 4.3.2 | 4.3.3 | 4.3.4 | 4.3.5Conclusion

4.4.1Coda

Prometheus Undone

5.1.1 | 5.1.2 | 5.1.3 | 5.1.4Appendix

The Tuberculosis Corpus

X.1.1 | X.1.2 | X.1.3Web Design

X.2.1 | X.2.2 | X.2.3 | X.2.4Installation Materials

X.3.1 | X.3.2 | X.3.3Index

Terminal Imaginaries, was produced in the spring 2021, funded in part by a Humanities, Arts, Science, and Technology Alliance and Collaboratory (HASTAC) scholarship and through funding from Indiana University’s College Arts and Humanities Institute (CAHI). A video installation for three projectors, it was developed when I was still winnowing my dissertation project. In the period shortly after creating the piece and the videos associated with it, I would go on to successfully defend a prospectus for this dissertation, which at the time was titled “Ontologies of Undoing” and addressed the ways that human remains produced value for medical institutions.

The problems with that prospectus, and the Terminal Imaginaries installation, were similar: I was still being too vague in my approach, and I had not cobbled together a completely forthright understanding of the history of medicine. This installation project helped me spend more time with a small collection of images, and it afforded me time to think through the creative, aesthetic modes I used to understand how those images operated. This project formulated an exploratory approach to the history of medicine, which inspected a wide set of materials from around the turn of the twentieth century. This work would form the spine of a successive installation, Tuberculous Imaginaries (3.2.4; 3.2.5), and the basis of my visual culture critique discussed earlier in this dissertation (1.1.2; 2.1.2).

Terminal Imaginaries was never shown to the public, but instead was developed and displayed in the garage of the condo where my wife (then girlfriend) and I lived (fig. 1). I built the installation during the Covid-19 lockdown, before either my wife or I got our first vaccines, and so it was never shown because of the limitations of that moment. I displayed it virtually as part of the Media School’s annual graduate conference, Common Ground, in spring 2021.

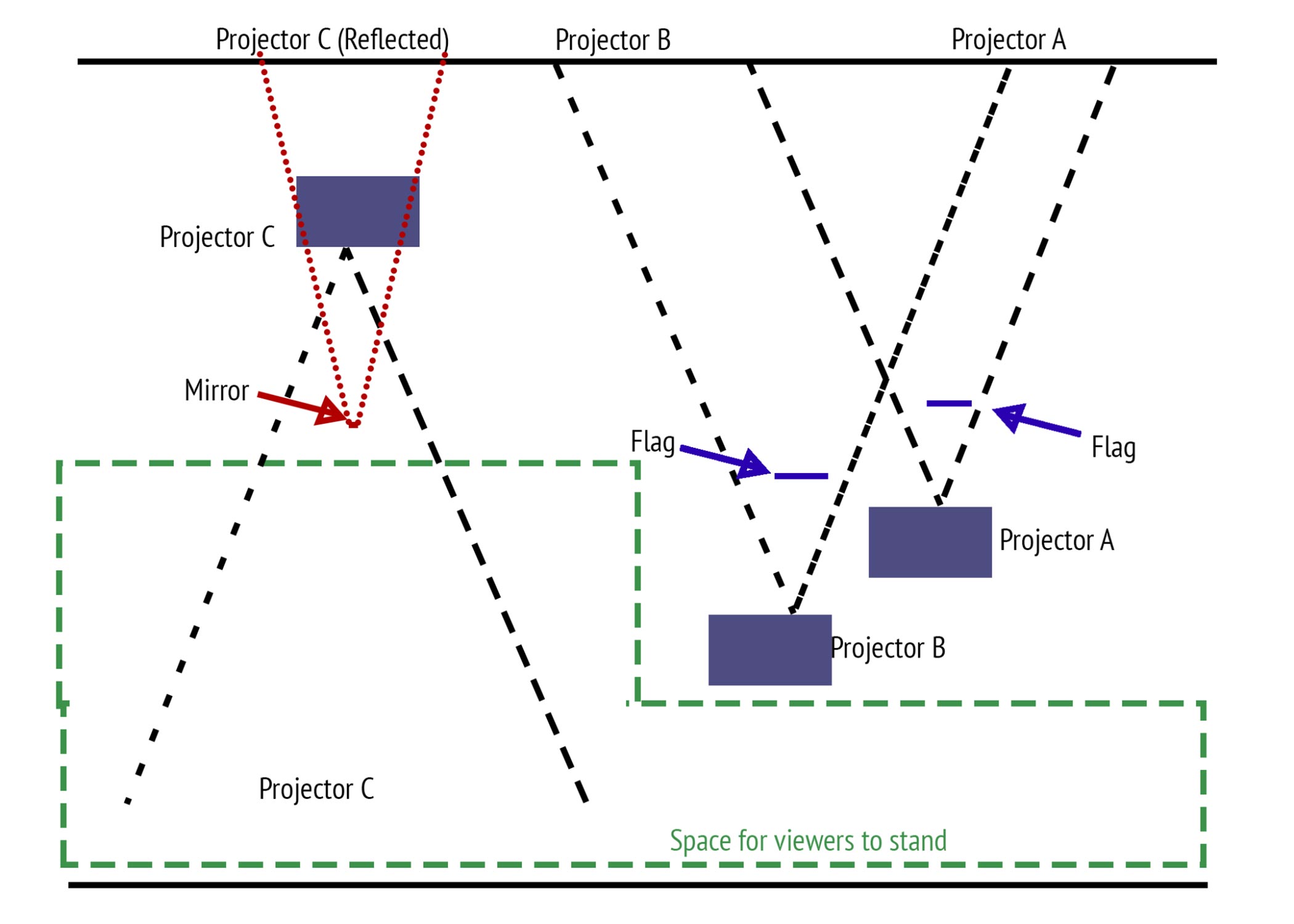

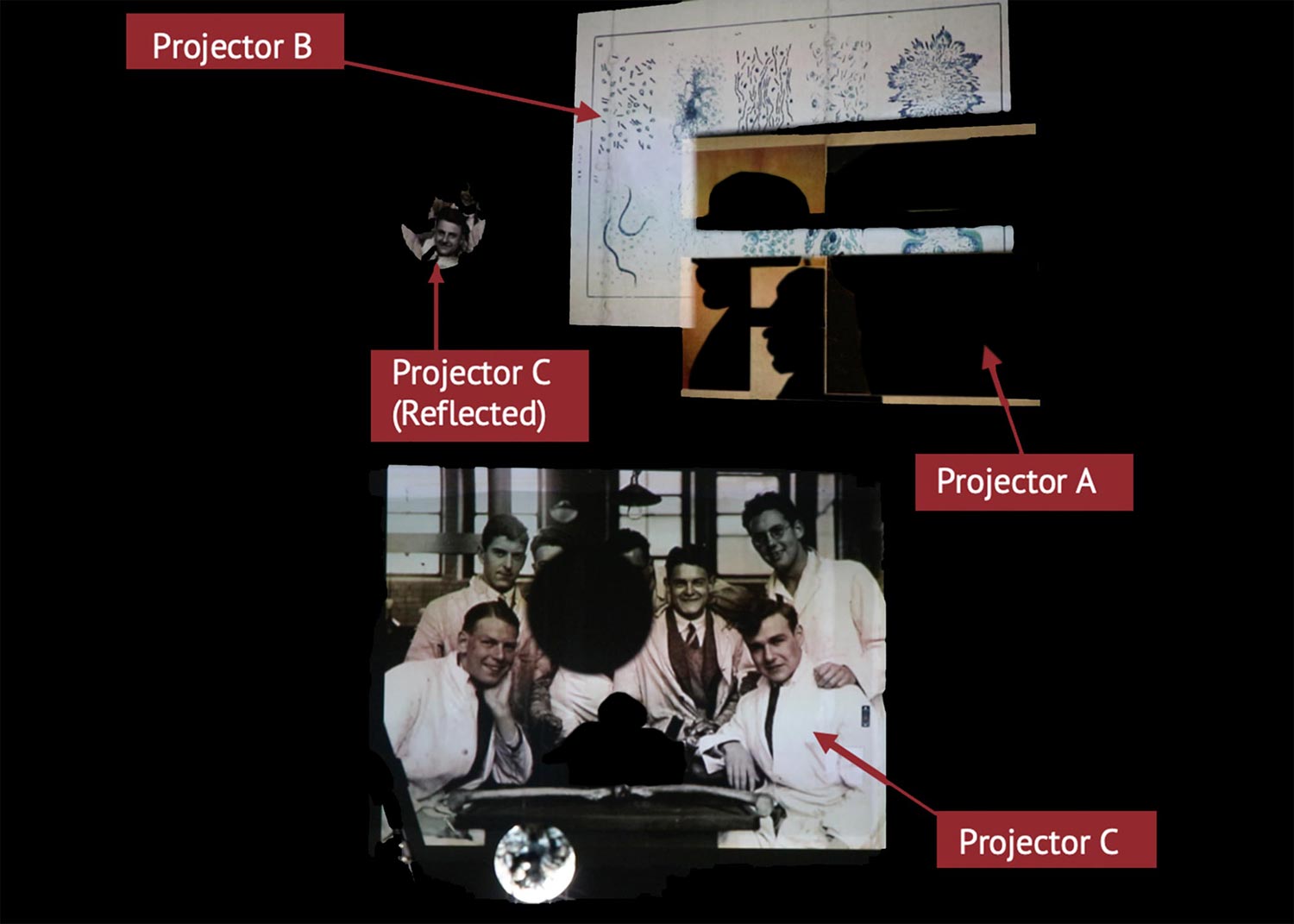

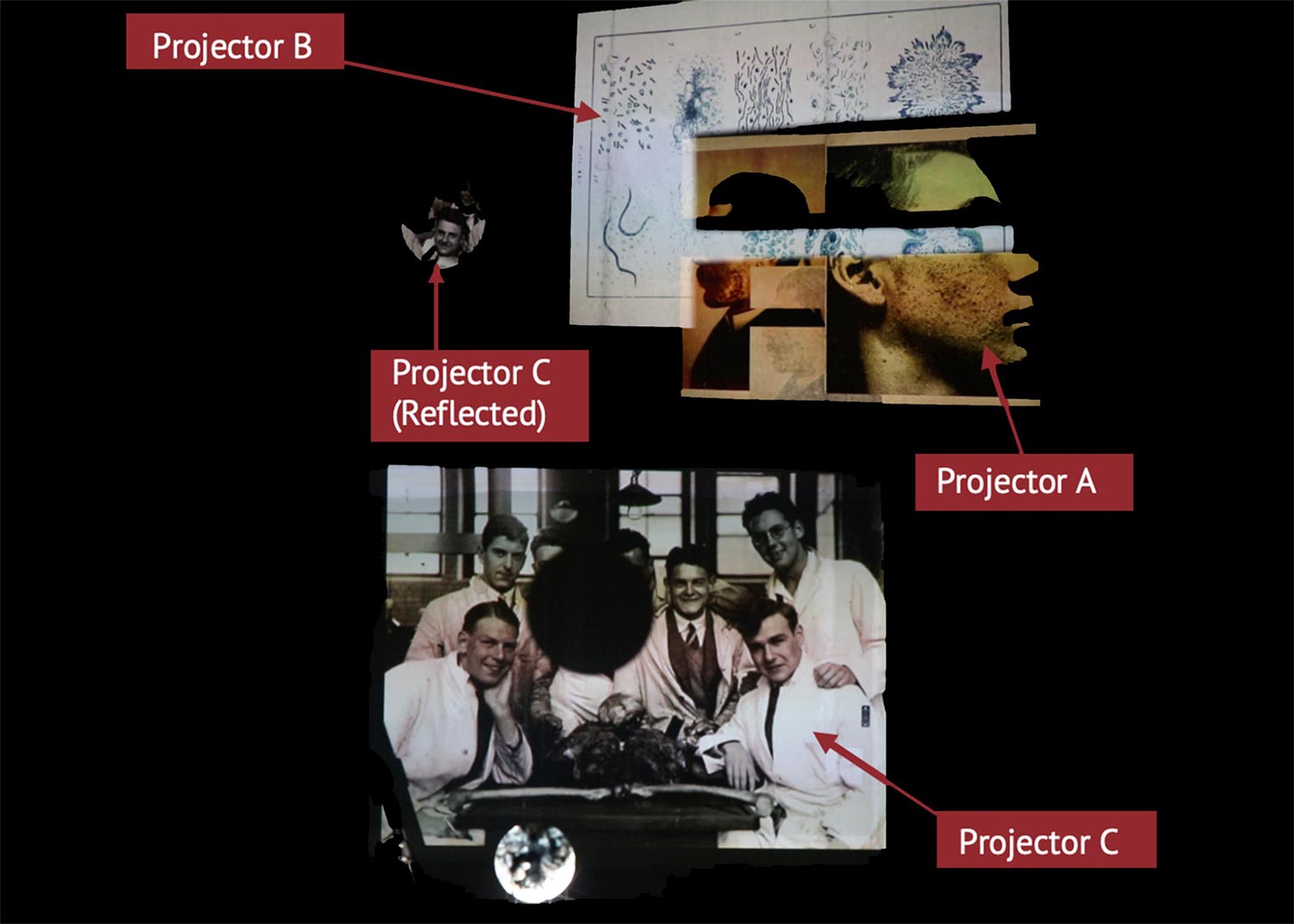

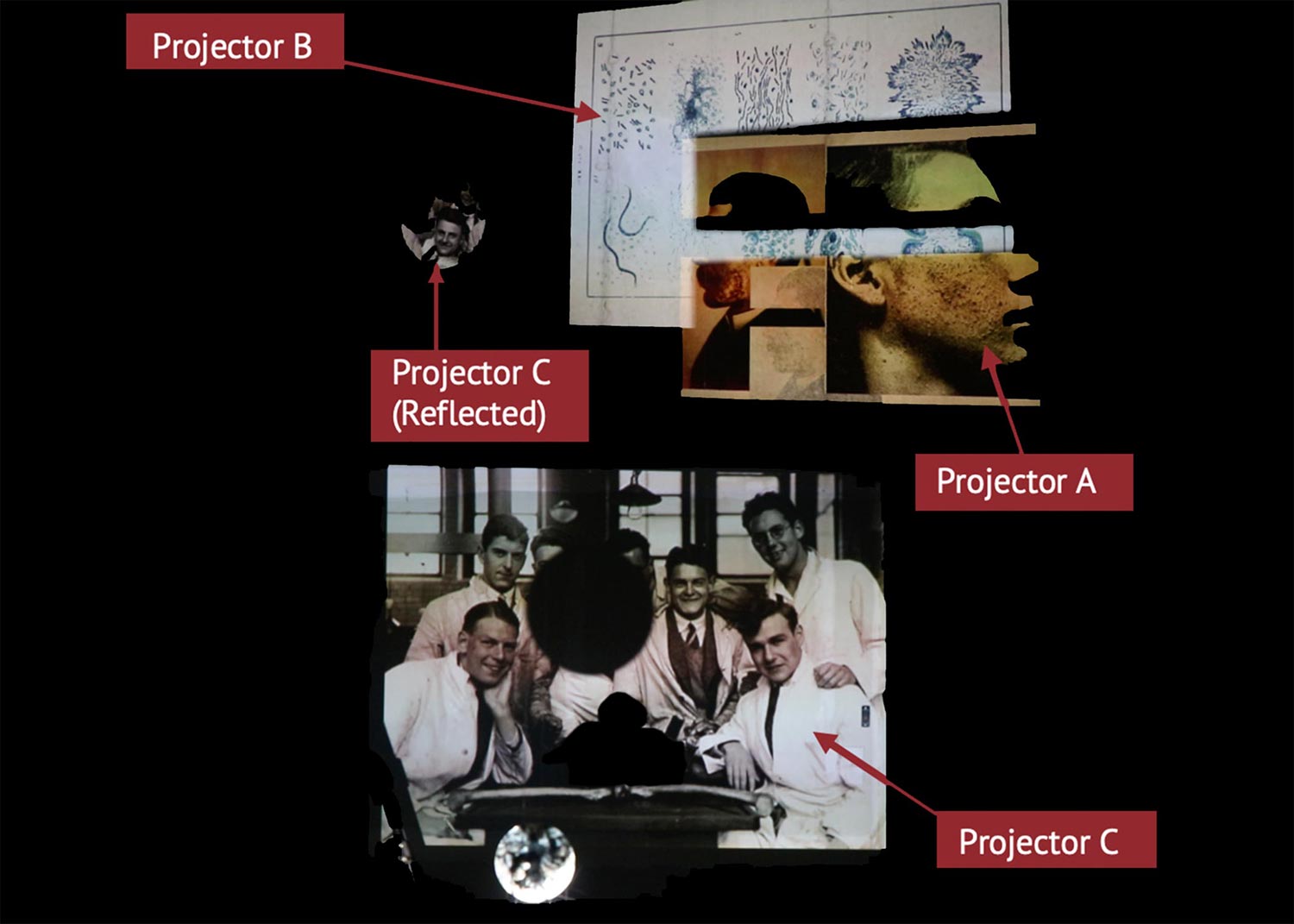

The work was made from three projectors and three corresponding mini computers,1 which ran the video feeds as a looping .mov file through the open source VLC media player. In addition to these video feeds, the projectors were mounted on tables with black paper flags and a circular mirror hanging in front of the light beams (fig. 2). While never displayed, I had hoped the waist high projectors would make an audience self-conscious of their presence in the room, of their bodies, and to subtly steer them around the space.2 Each of the three projectors displayed a different set of images (fig. 3). In the installation’s corresponding website,3 I wrote,

Each projector has a different kind or genre of image. Projector A uses materials sourced from dermatology textbooks; Projector B’s images were pulled from different anatomical atlases (most notably Dr. Henry Gray and Warren H. Lewis’ Anatomy of the Human Body, also known as Gray’s Anatomy); Projector C features images of anatomical classes posing in front of their anatomized subject. Together, these projectors present a meditation on modern medicine’s visual culture.4

-

I refer to the mini computer as a product sold today, which are computers about the size of half of a hardcover book. This is different than minicomputer, which refers to a kind of computer developed in the late twentieth century that was different than a supercomputer or personal computer. ↩

-

If I am honest, however, my skill with spatial installs needs more practice and consideration. It is a limitation of this project and the Tuberculous Imaginaries project discussed later in this chapter (4.3.1). ↩

-

This website is no longer online, and I have lost most of the web-based writing related to that installation. ↩

-

Sean Purcell. “Welcome to Terminal Imaginaries”. Post Made Around 2021. ↩