Introduction

Specimen Studies

0.1.1 | 0.1.2 | 0.1.3 | 0.1.4 | 0.1.5Methods

0.2.1 | 0.2.2The Structure of this Dissertation

0.3.1Tuberculosis' Visual Culture

Visual Practices in Medical Culture

1.1.1 | 1.1.2 | 1.1.3Seeing and Settling in the Sanatorium Movement

1.2.1 | 1.2.2 | 1.2.3 | 1.2.4 | 1.2.5Teaching Public Health

1.3.1 | 1.3.2 | 1.3.3 | 1.3.4 | 1.3.5Representing Doctors in Tuberculous Contexts

1.4.1 | 1.4.2Using Human Specimens in the Study of Tuberculosis

Seeing Disease in Methyl Violet

2.1.1 | 2.1.2 | 2.1.3 | 2.1.4Case Histories

2.2.1 | 2.2.2 | 2.2.3 | 2.2.4Visceral Processes

2.3.1 | 2.3.2Relation

2.4.1 | 2.4.2 | 2.4.3Arts-Based Inquiry

Introduction

3.1.1 | 3.1.2 | 3.1.3 | 3.1.4Terminal Imaginaries & Tuberculous Imaginaries

3.2.1 | 3.2.2 | 3.2.3 | 3.2.4 | 3.2.5 | 3.2.6Dermographic Opacities

3.3.1 | 3.3.2 | 3.3.3 | 3.3.4Tactical Pretensions

3.4.1 | 3.4.2 | 3.4.3Designing Opacity

A Shift towards the Anticolonial

4.1.1 | 4.1.2 | 4.1.3 | 4.1.4Refusals and Opacities

4.2.1 | 4.2.2 | 4.2.3 | 4.2.4Digital and Ethical Workflows

4.3.1 | 4.3.2 | 4.3.3 | 4.3.4 | 4.3.5Conclusion

4.4.1Coda

Prometheus Undone

5.1.1 | 5.1.2 | 5.1.3 | 5.1.4Appendix

The Tuberculosis Corpus

X.1.1 | X.1.2 | X.1.3Web Design

X.2.1 | X.2.2 | X.2.3 | X.2.4Installation Materials

X.3.1 | X.3.2 | X.3.3Index

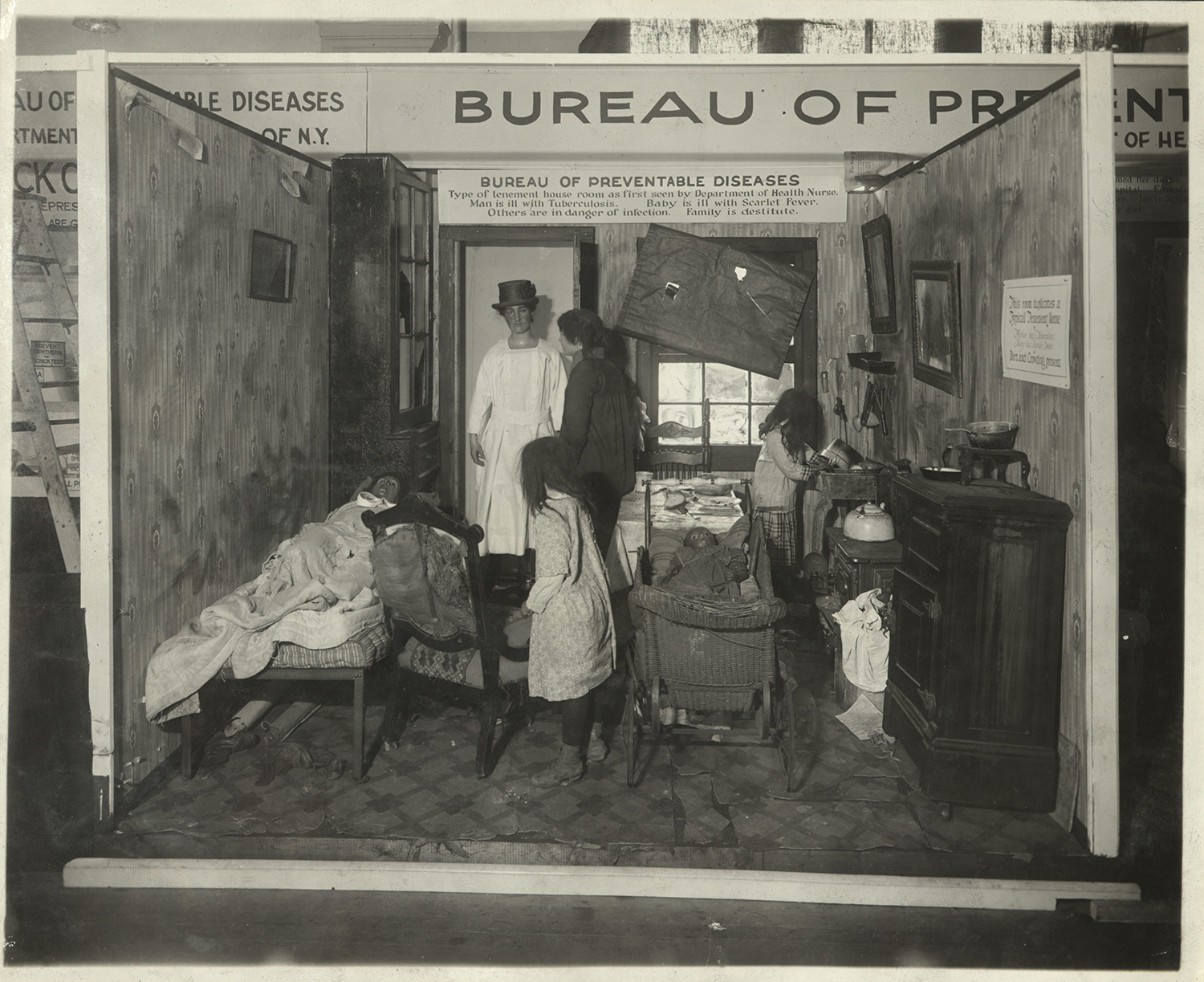

In November 1921, the American Public Health Association held a Public Exposition as part of its fiftieth annual meeting. One of many events held over a fortnight, the Public Exposition included displays by each of New York City’s departments, contests, and an area called “a Children’s Highway to Health”.1 The Bureau of Preventable Diseases’ installation included a pair of dioramas showing the value of public health nurses and other social programs designed to combat communicable diseases (figs. 1 & 2). The captions included in the paired exhibits read as follows. The first, a ‘before’ image, reads,

”Type of tenement house room as first seen by Department of Health Nurse. Man is ill with Tuberculosis. Baby is ill with Scarlet Fever. Others are in danger of infection. Family is destitute.”

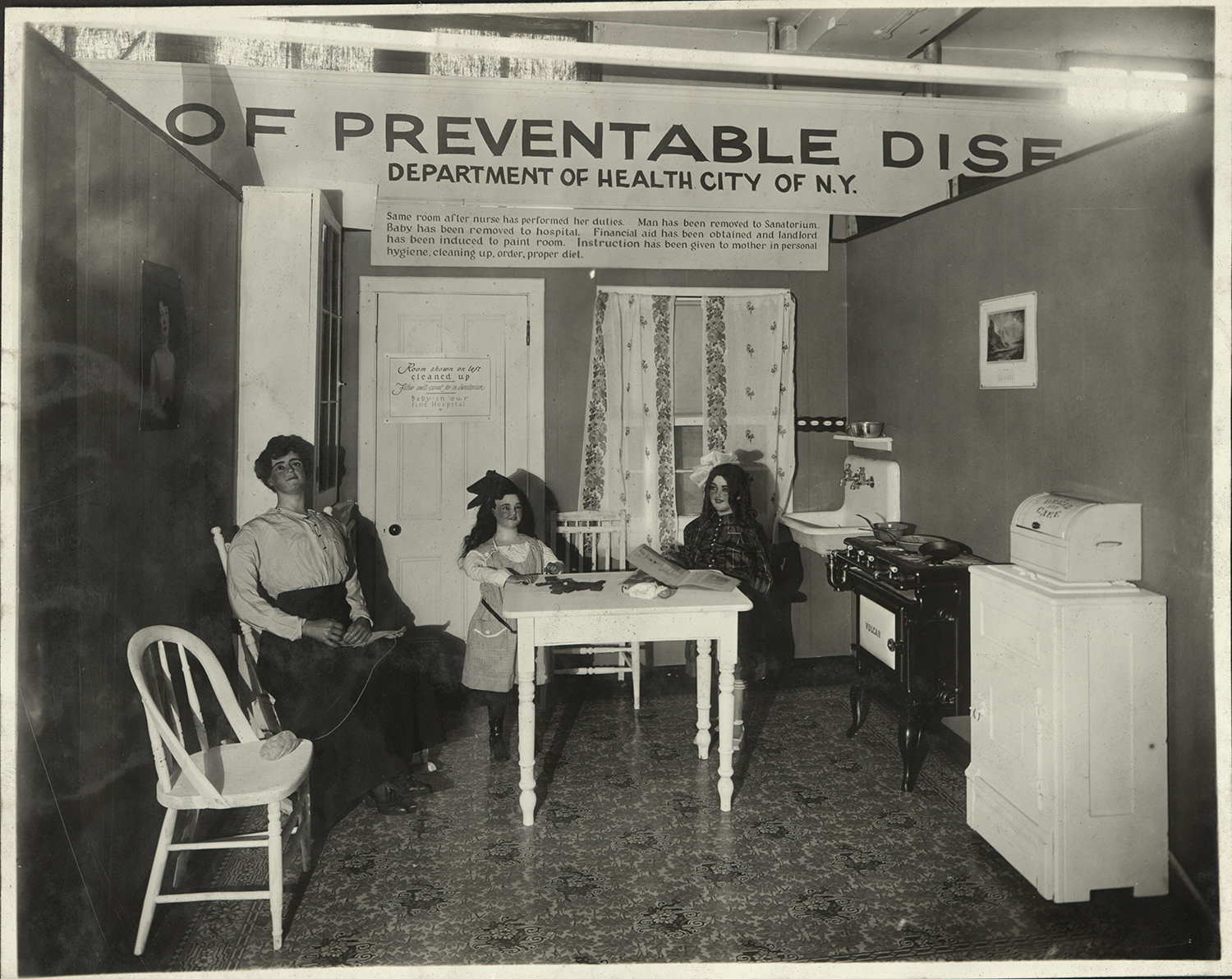

And the second, an ‘after’ image, reads,

”Same room after nurse has performed her duties. Man has been removed to Sanatorium. Baby has been removed to hospital. Financial aid has been obtained and landlord has been induced to paint room. Instruction has been given to mother in personal hygiene, cleaning up, order, proper diet.”

These two images serve as an example of the kind of representations which defined the discourse around hygiene and tuberculosis at the turn of the twentieth century. I use hygiene as a short hand to discuss the interlinked developments in western cultures regarding personal cleaning, public health, and the management of foreign bodies—both bacteria, as well as immigrants in the United States.2 Hygienic interventions—like public health exhibitions, the work of the public health nurse, as well as the management of disease taught at public sanatoria and dispensaries (1.3.4)—targeted the bodies of poor, non-white, non-American, and disabled persons as spaces that deserved the health officials’ attention.

The Bureau of Preventable Diseases’ installation summarizes this logic simply. In the ‘before’ image there is a destitute family, unable to provide, repeatedly getting each other sick, and living in an unhealthy environment. In the after image, through the benevolence of the public health nurse, public funds, and the power of education, the family is restored to health. These images convey a few recurring themes in the images around tuberculosis: the contrast between clean and healthy, the association with public health and education, and the visual logic of an exhibition to convey to the masses the value of cleanliness. If the sanatorium’s visual representations were defined by an ordered cleanliness, a retreat from the urban (1.2.1), and spaces vacant of human subjects (1.2.2), hygiene was defined by an interest in contrasts: between clean and dirty, between healthy and sick, and between wealthy and poor.

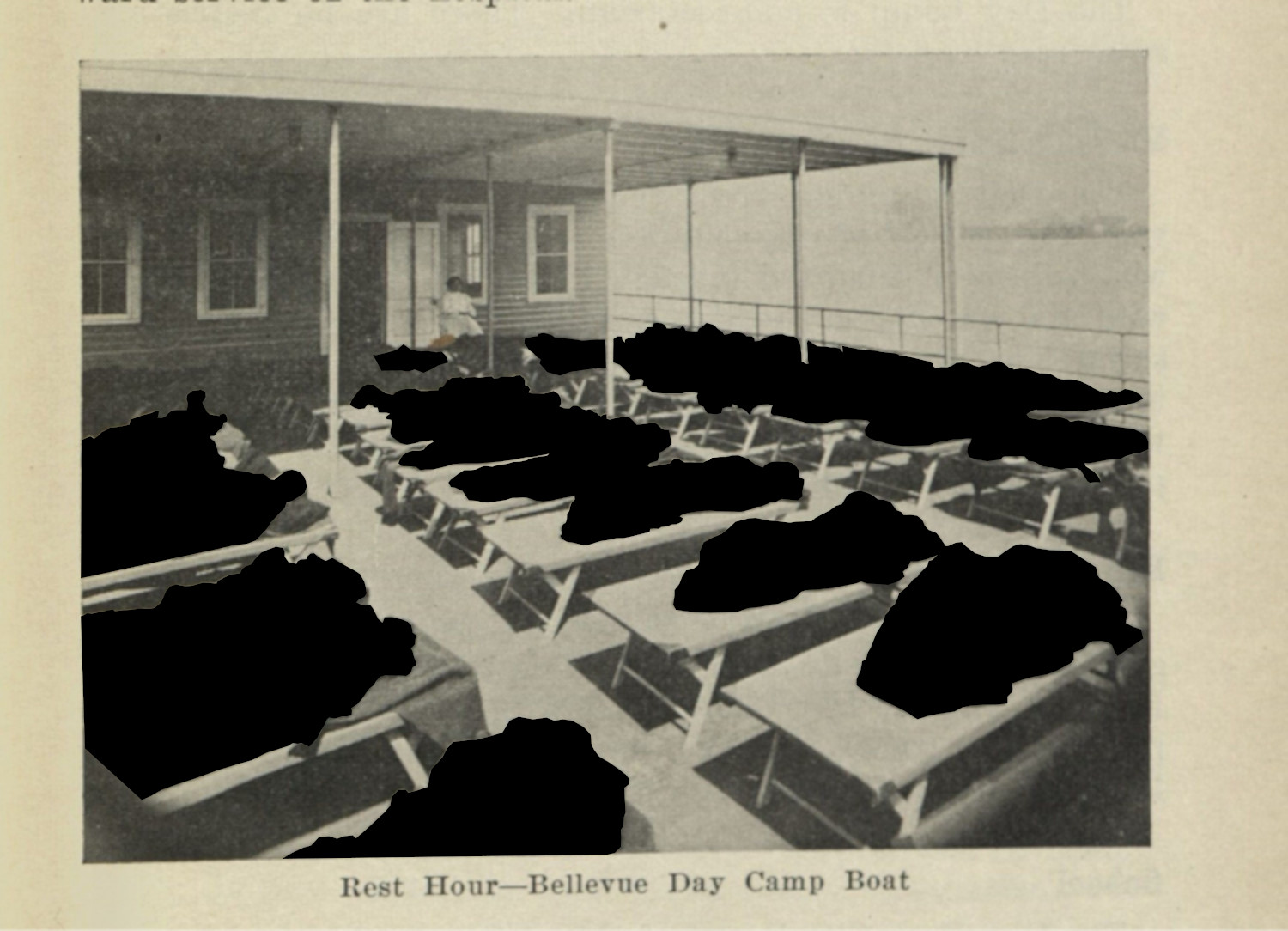

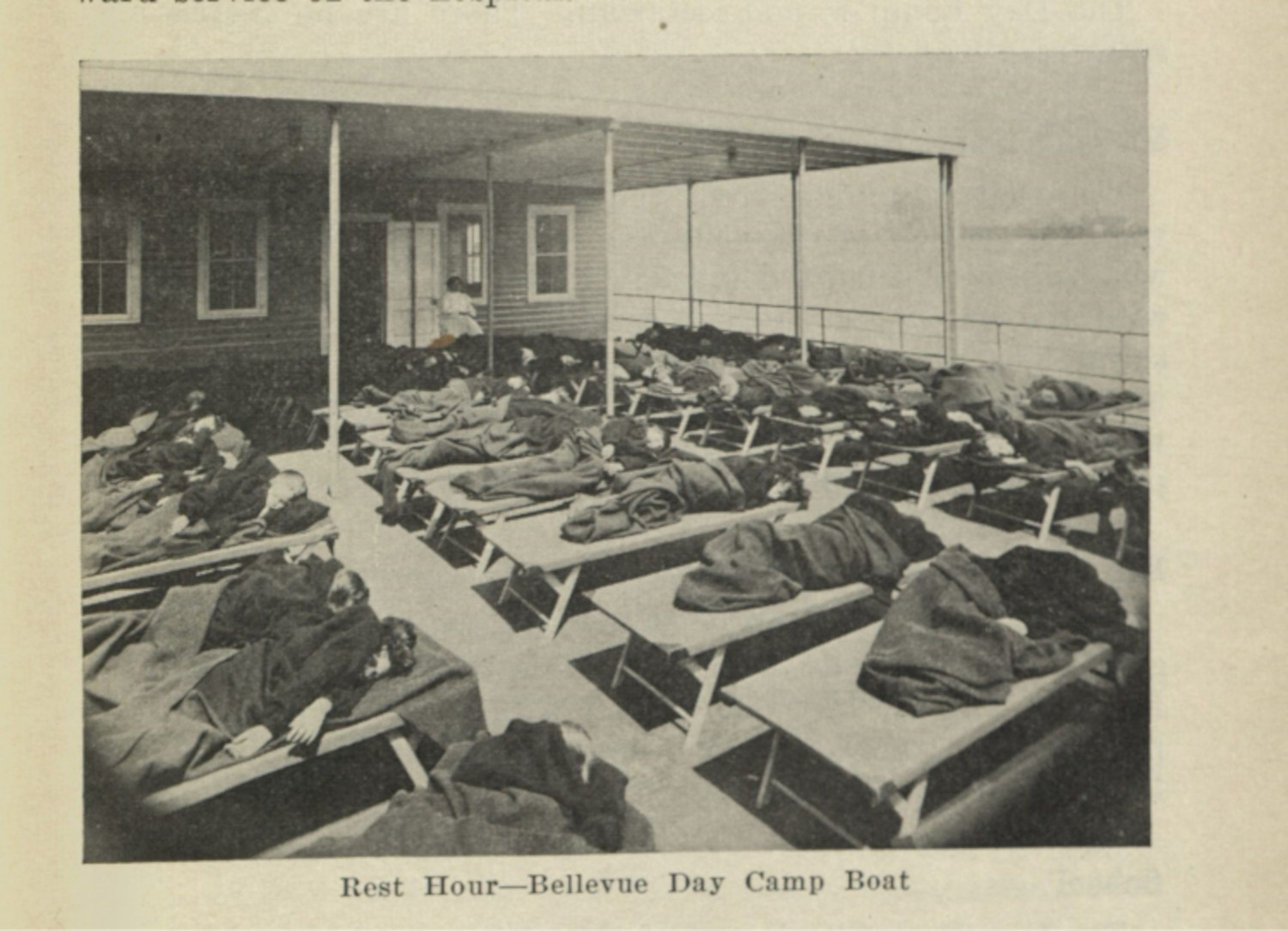

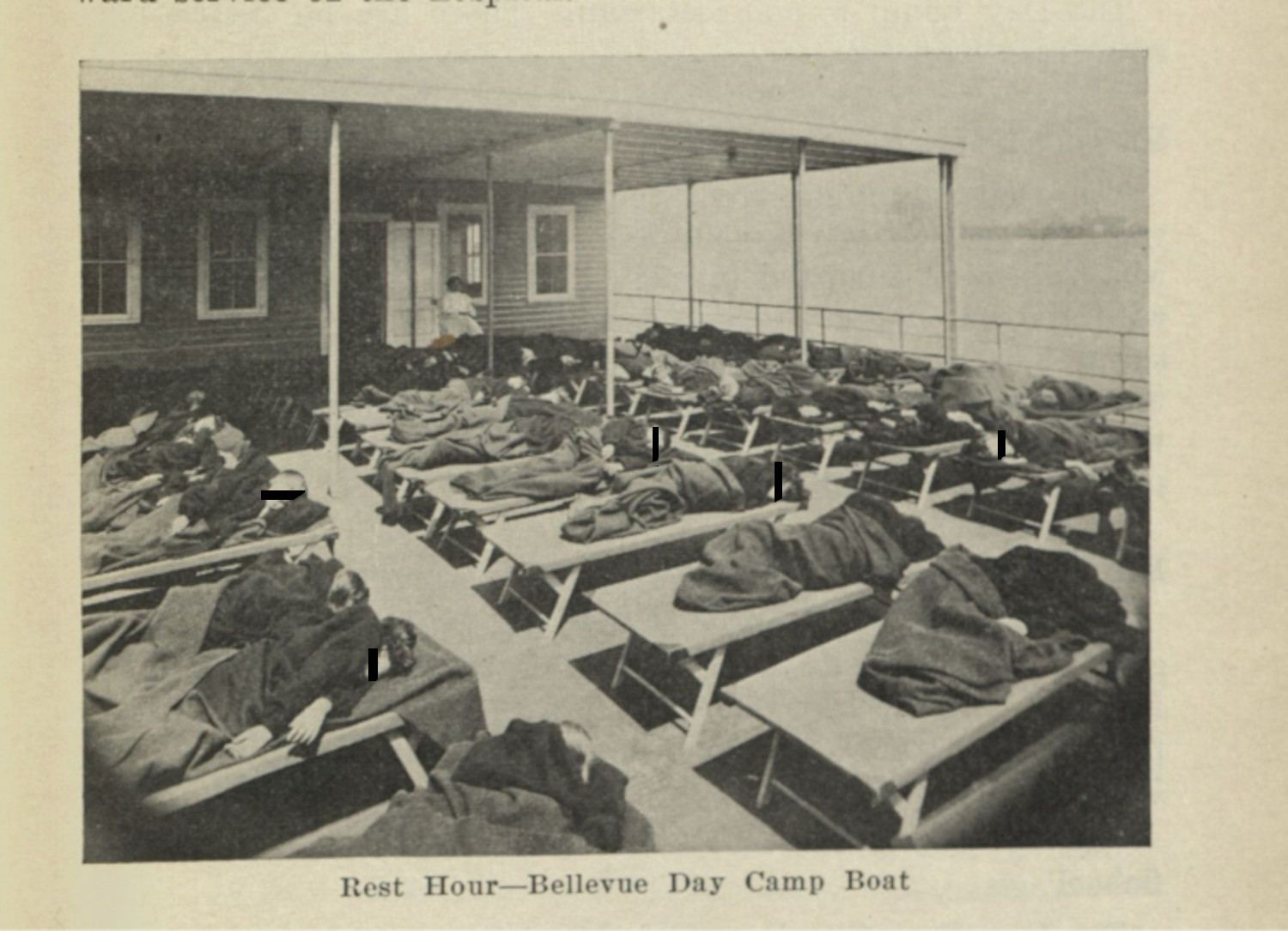

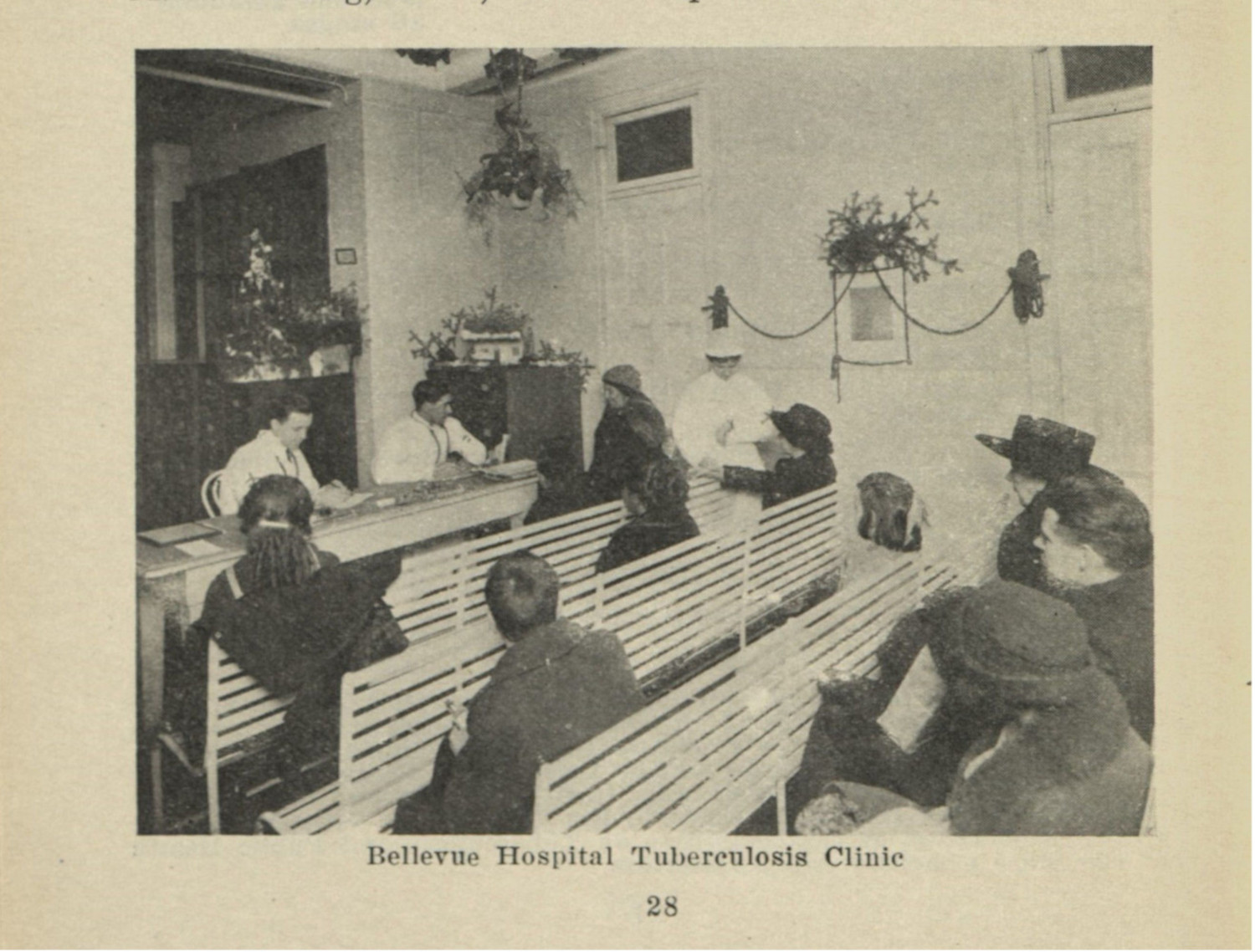

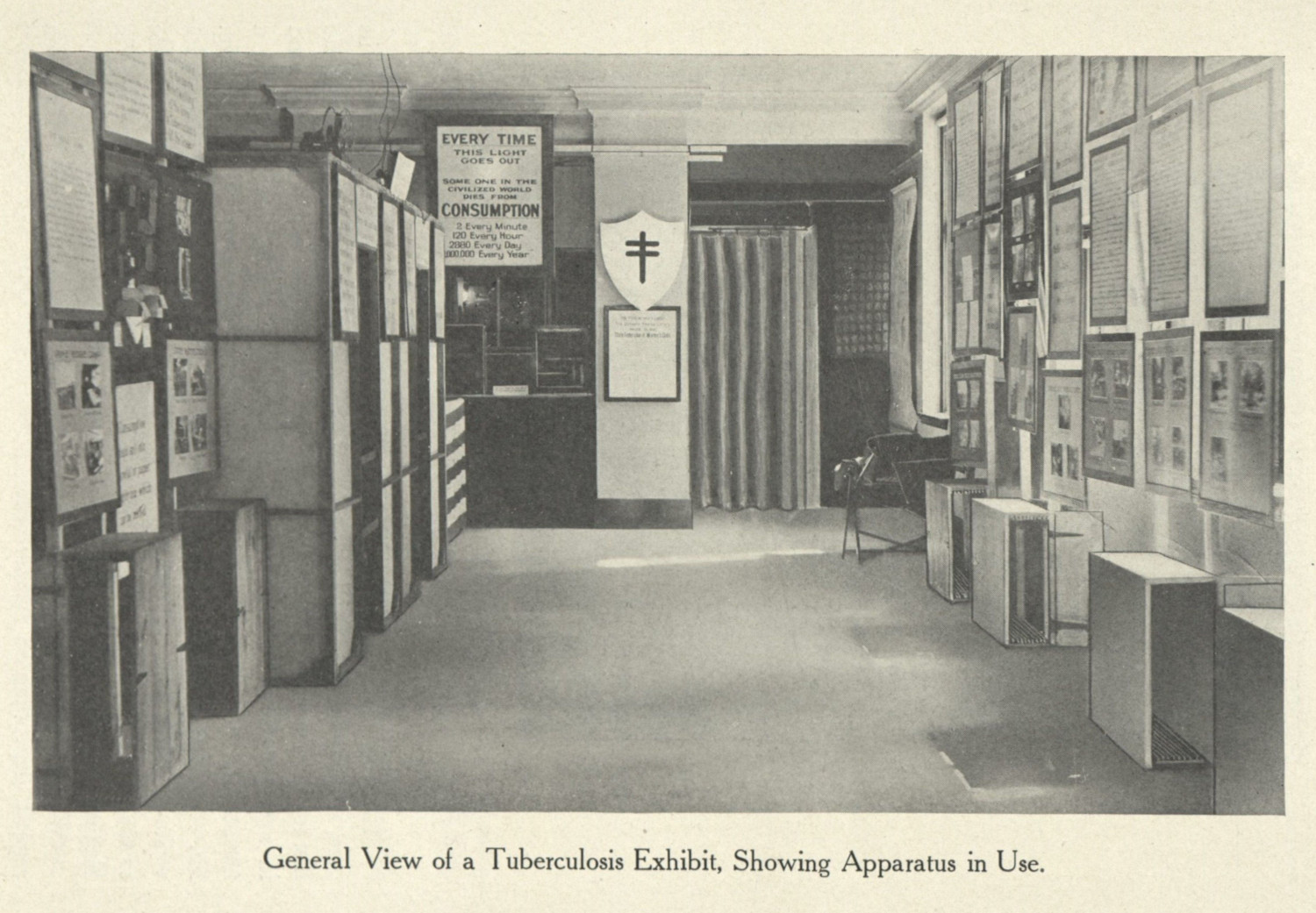

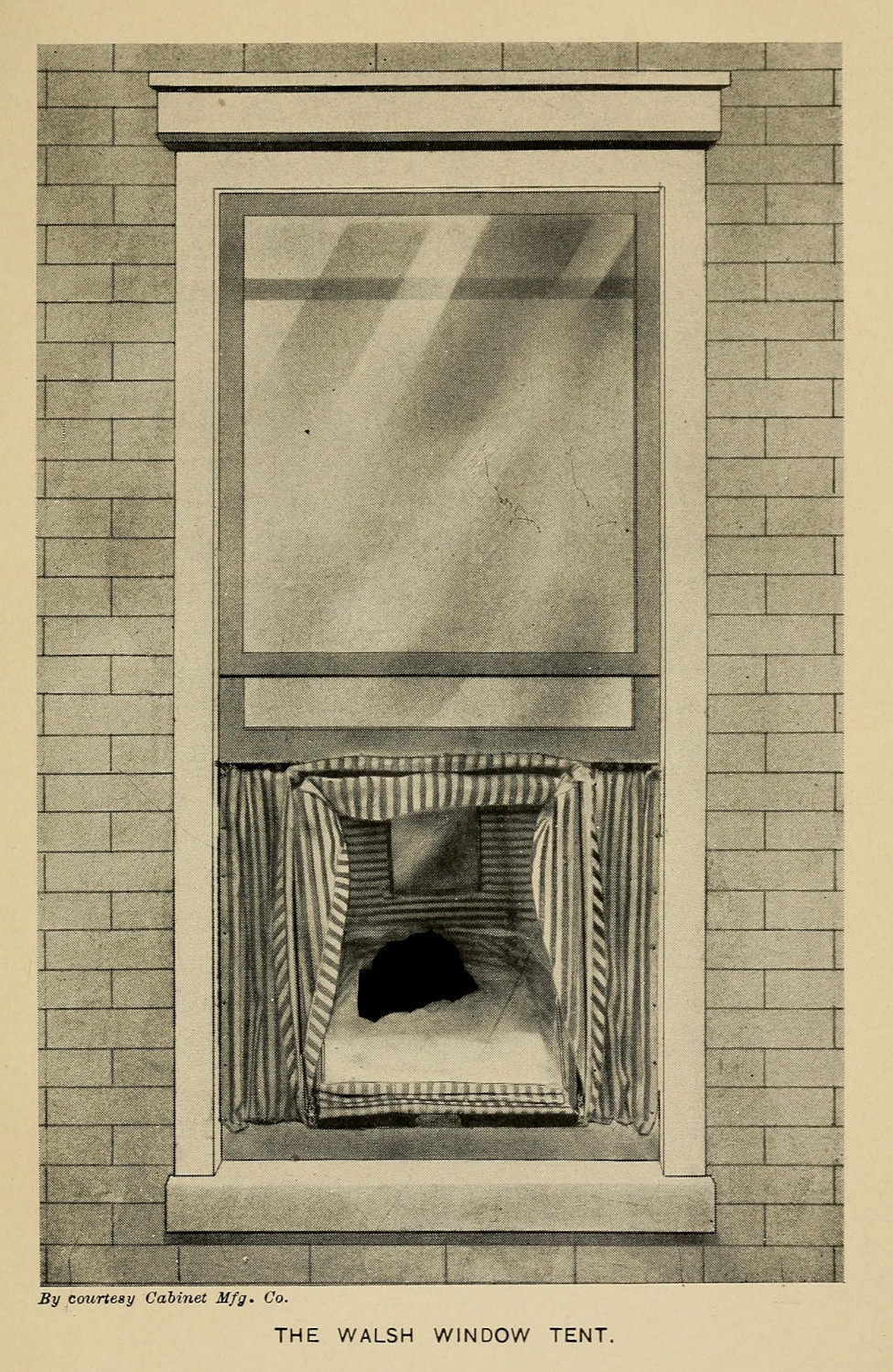

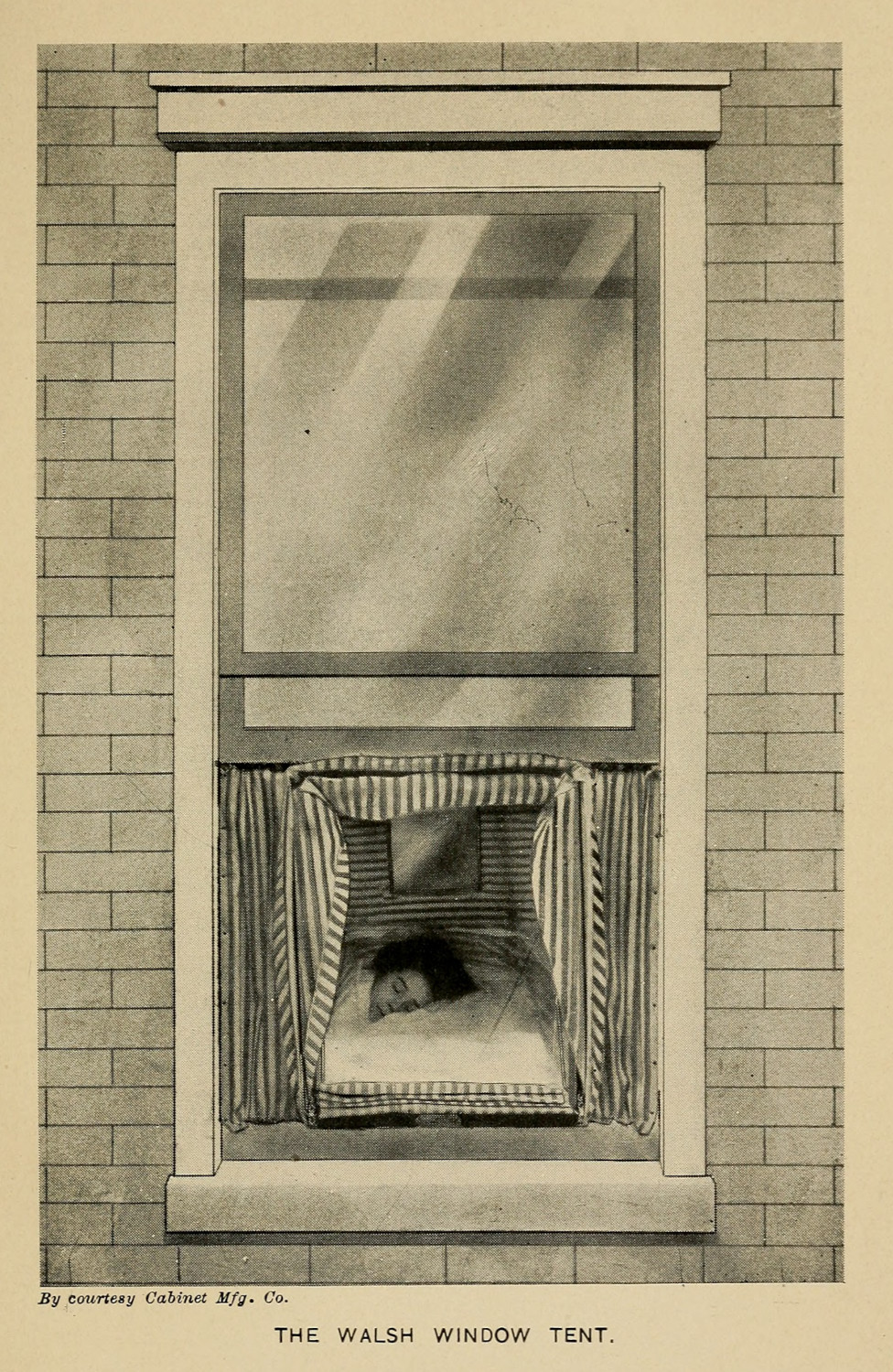

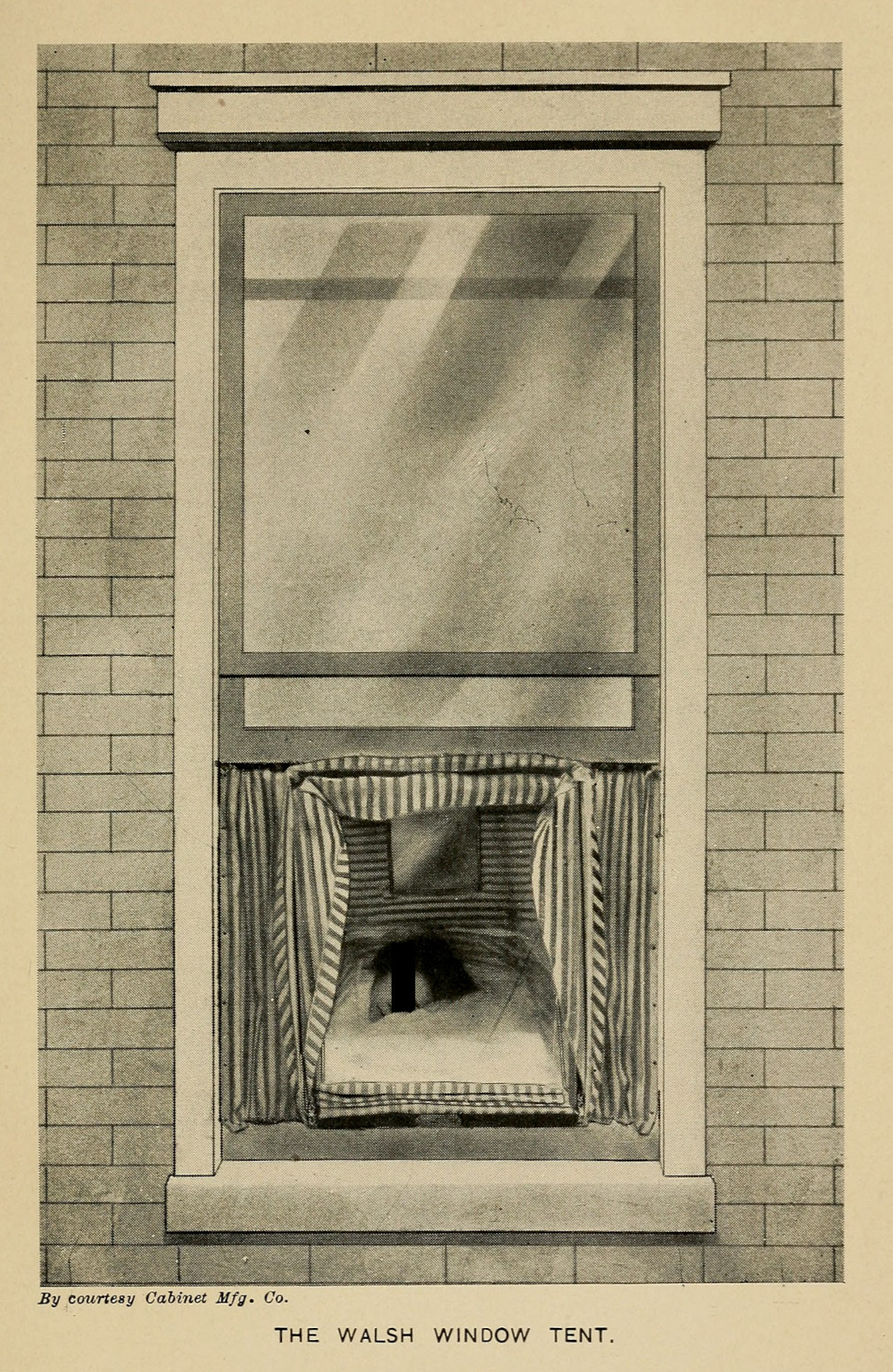

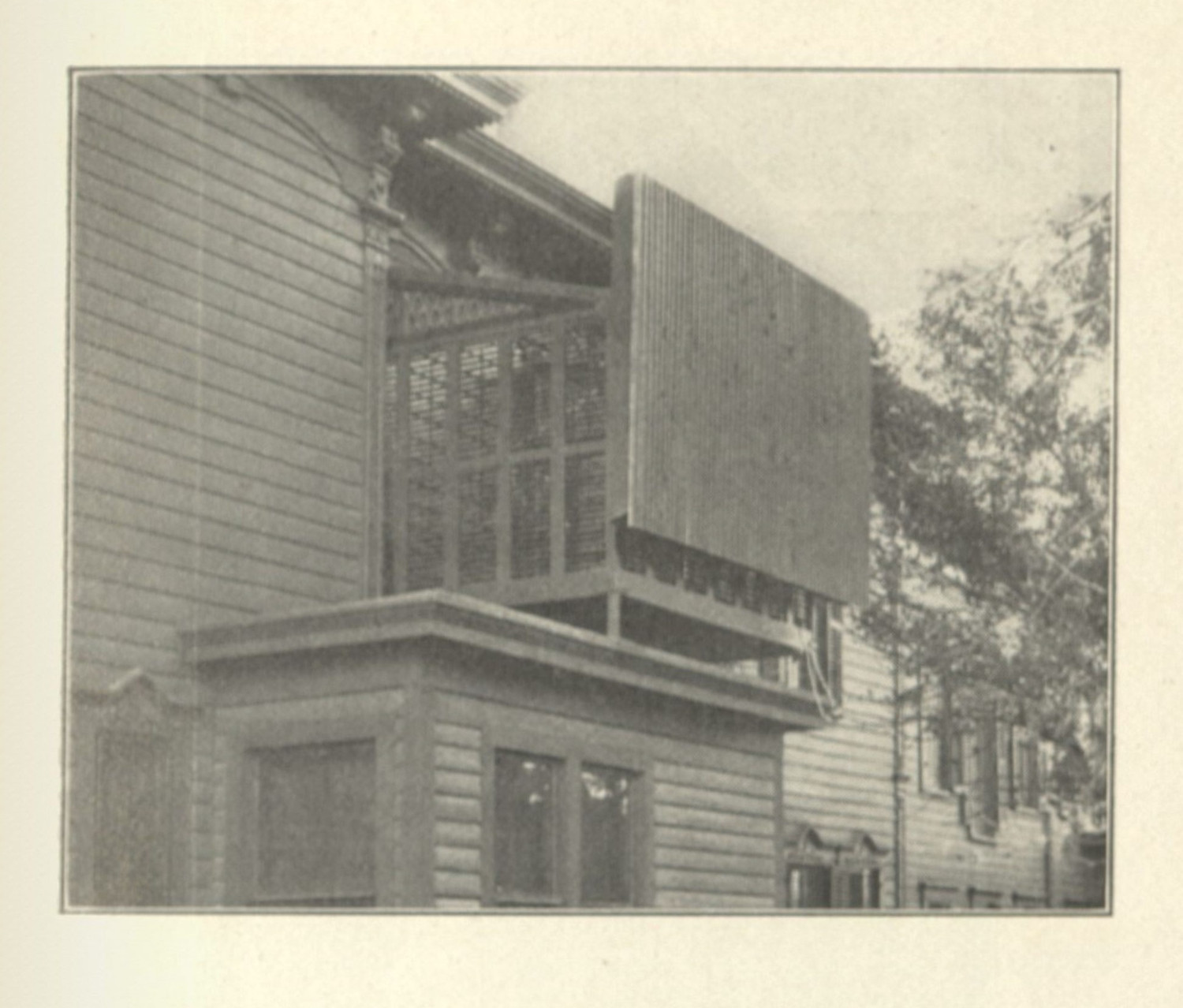

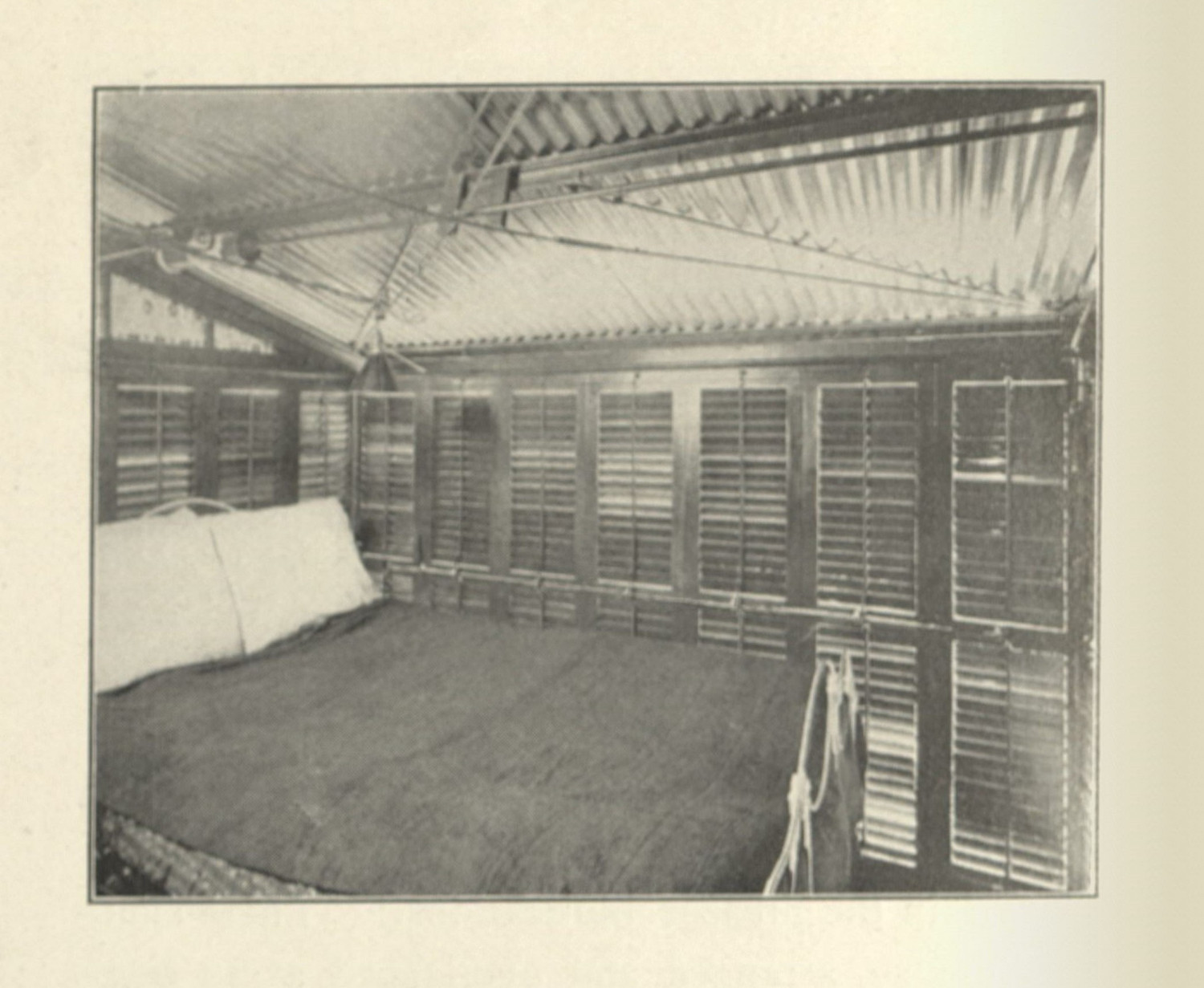

The public health interventions included a swath of different approaches to fighting tuberculosis, which included public institutions—sanatoria, day camps, and hospitals (figs. 3 & 4)—educational programs (figs. 5) (1.3.4), and at home interventions (figs. 6 - 8) (1.3.3). While the private sanatorium and health resort became an icon for the treatment of tuberculosis (1.2.3), its doors were often out of reach for poorer patients, and patients who lived in cities.

The way tuberculosis and its treatment was envisioned in the public health and hygienic discourses of the period provides a helpful contrast to how tuberculosis patients were treated in the sanatorium, especially for charity cases. Just as with the two images which began this section (figs. 1 & 2), there is an implicit judgement in the way public health gazes at the urban poor: these images express a view that disease is the result of an unhealthy lifestyle, and that that unhealthy lifestyle was the result of a lack of education, character, or ability (1.3.4). The logic of inferiority, entangled with the eugenicist associations of birth to character, aptitude, and morality, defines the written and visual rhetoric around the disease (1.3.5).

The purpose of this case study is to interrogate these images, looking at how hygienic discourses reify classist and racist ideologies around health (1.3.5). The aesthetics of hygiene operate through a specific, classed, raced, and abled framing by doctors, public health officials, and well-meaning laypeople. In articulating a binarist framing—one which is right, healthy, and safe, and one which is wrong, unhealthy, and dangerous—public health interventions positioned the subjects of these unhygienic before images as a public health threat. The people who were captured in these images usually were non-white, poor, and disabled (1.3.2), this meant that their race, class, and ability was explicitly tied to being dirty, contagious, and a public threat (1.3.5). Coded into this rhetoric is an implicit eugenicist logic: sick people—specifically sick, non-white, disabled people—represented a danger to infect and harm the broader able-bodied populace (1.3.5).

-

The contests included a best baby contest, awards for individuals who lost weight, and a “search for a perfect foot among women”. The children’s programming featured a sailor who manned a lighthouse in “The Harbor of Health” and a “Health Clown” which cavorted during the festivities.

The New York Times. “Health Exposition to Open Tomorrow.” November 13, 1921. ↩

-

Ward, Peter. The Clean Body: A Modern History. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2019. 141. ↩