Introduction

Specimen Studies

0.1.1 | 0.1.2 | 0.1.3 | 0.1.4 | 0.1.5Methods

0.2.1 | 0.2.2The Structure of this Dissertation

0.3.1Tuberculosis' Visual Culture

Visual Practices in Medical Culture

1.1.1 | 1.1.2 | 1.1.3Seeing and Settling in the Sanatorium Movement

1.2.1 | 1.2.2 | 1.2.3 | 1.2.4 | 1.2.5Teaching Public Health

1.3.1 | 1.3.2 | 1.3.3 | 1.3.4 | 1.3.5Representing Doctors in Tuberculous Contexts

1.4.1 | 1.4.2Using Human Specimens in the Study of Tuberculosis

Seeing Disease in Methyl Violet

2.1.1 | 2.1.2 | 2.1.3 | 2.1.4Case Histories

2.2.1 | 2.2.2 | 2.2.3 | 2.2.4Visceral Processes

2.3.1 | 2.3.2Relation

2.4.1 | 2.4.2 | 2.4.3Arts-Based Inquiry

Introduction

3.1.1 | 3.1.2 | 3.1.3 | 3.1.4Terminal Imaginaries & Tuberculous Imaginaries

3.2.1 | 3.2.2 | 3.2.3 | 3.2.4 | 3.2.5 | 3.2.6Dermographic Opacities

3.3.1 | 3.3.2 | 3.3.3 | 3.3.4Tactical Pretensions

3.4.1 | 3.4.2 | 3.4.3Designing Opacity

A Shift towards the Anticolonial

4.1.1 | 4.1.2 | 4.1.3 | 4.1.4Refusals and Opacities

4.2.1 | 4.2.2 | 4.2.3 | 4.2.4Digital and Ethical Workflows

4.3.1 | 4.3.2 | 4.3.3 | 4.3.4 | 4.3.5Conclusion

4.4.1Coda

Prometheus Undone

5.1.1 | 5.1.2 | 5.1.3 | 5.1.4Appendix

The Tuberculosis Corpus

X.1.1 | X.1.2 | X.1.3Web Design

X.2.1 | X.2.2 | X.2.3 | X.2.4Installation Materials

X.3.1 | X.3.2 | X.3.3Index

This dissertation looks at the ways biomedical scientists studied tuberculosis in the years following its microbial discovery. While there is a great deal of cultural and scientific baggage associated with the disease (0.1.2; 1.1.1), my interest is much more in the ways scientists constructed the disease from the bodies of patients. This project is more closely aligned with science and technology studies (STS), and its approach to the social construction of science—that is, scientific facts are the result of social processes, from access to materials and technologies to the ideological underpinnings which guide research.1

My framework is indebted to Kim TallBear’s use of Stuart Hall. Writing of the coproduction of science in her book Native American DNA, she describes how biological phenomena are encoded in cultural processes. She writes,

Rather than being discrete categories where one determines the other in a linear model of cause and effect, ‘science’ and ‘society’ are mutually constitutive—meaning one loops back in to reinforce, shape or disrupt the actions of the other, although it should be understood that, because power is held unevenly, such multidirectional influences do not happen evenly.2

TallBear’s argument keys into how race and tribal identity are coded through DNA, pointing to how these discourses are a byproduct of the racial schemas assumed by the researchers studying Indigenous communities.3 Scientists coproduce a reality, and the racial ideologies, entangled as they are with modern medicine’s love of eugenics and racial science, maintain themselves. This is to say that because scientists at the turn of the twentieth century believed race to be a natural phenomenon, they looked for racial determinants of the phenomena they studied. In the case of tuberculosis, Black patients were assumed to be sick at higher rates than white patients because of a supposed racial inferiority, and not because the systems of health actively harmed Black subjects (1.3.5).4

My interest is in the covert ways ideas are made through the production of specimens. A media object, the specimen is any material or information that has been taken from someone or something and staged in a scientific context. I use the term ‘media object’ to refer to the representation processes encoded into scientific research materials. Object, which I will define in more detail in the next section (0.1.4), refers to something that has been stripped of its original context in such a way as to make it representative for a knowledge claim. Importantly for human contexts, a research object is produced through a process of objectification—which strips certain historical, cultural, personal connections from the research material. A patient is a research subject, and the organ taken from them is a research object.5 I connect this to media studies because that field has been historically interested in the processes and representation enabled by certain technologies. A technology like film or radio mediates a message within its own technologically specific representational affordances, and mediation refers to the ways that technology enables a representational encounter. The specimen mediates a scientist’s observation, as it is framed through technologies of preservation—photography, wet tissue preservation, x-rays—and through the delicate framing of biological material (2.3.1; 2.3.2).6

Specimens can be wet tissues preserved in jars (2.2.1; 2.3.1), blood samples, sputum samples, x-rays, clinical photographs, patient histories (2.2.2), or recorded biometrics. The specimen is never a natural object, so much as the byproduct of an extractive process which frames it as natural. Every action that brings it into a scientific context was made through human practices and human technologies. How it is taken, how it is framed, and how the scientist describes the phenomenon on display are the result of a scientist making decisions: deciding to document a patient’s symptoms, deciding to autopsy the patient’s body, deciding to cut an organ from that body, deciding to place that organ into spirit, and deciding how to describe it in their collection (2.3.1; 2.3.2).7

In addition to TallBear’s read of Hall’s work on coproduction, I am equally indebted to the Jamaican-British scholar’s essay “Encoding/Decoding.” In the essay, Hall describes how television works in such a way as to give agency to both the producers of information and those that receive it. There is a kind of force in the ways dominant meanings are understood, which are entangled with a kind of discursive training. Hall writes,

since these mappings are ‘structured in dominance’ but not closed, the communicative process consists not in the unproblematic assignment of every visual term to its given position within a set of prearranged codes, but of performative rules—rules of competence and use, of logics-in-use—which seek actively to enforce or pre-fer one semantic domain over another and rule items into and out of their appropriate meaning-sets.8

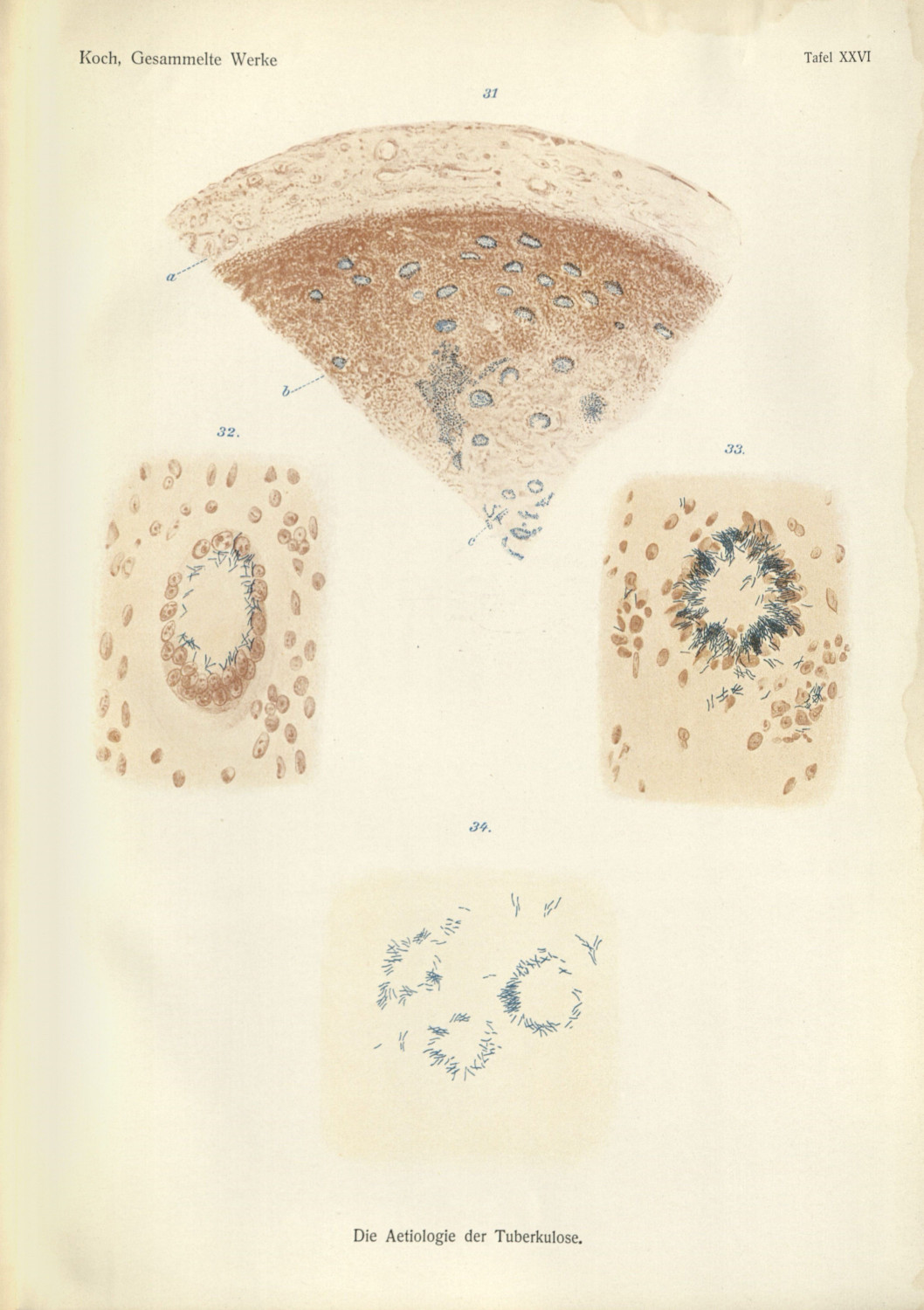

Hall’s “performative rules” assume that audiences are taught specific technical or genre conventions regarding the meaning of a given piece of art. In the essay, he is referring to television conventions, diffusing the one-way transmission of information in moving image production. What is useful for me, and for this dissertation, is that this framework can also be used to understand scientific argumentation. Medical doctors have long been trained in various visual techniques—clinical vision (1.2.1; 2.2.2), microscopy(2.1.3)—and these forms of argument take time, expertise, and professional standardization to become taken for granted within an scientific discipline. In order to see Mycobacterium tuberculosis through a microscope, a doctor first needed to know how to operate that tool, to accept what they see, and to agree with the method of isolating that material (2.2.1; 2.2.2) (fig. 1).9 Scientific observers are primed to read a specimen in a specific way, and the producers of those research objects have to match those same expectations.

The production of specimens is entwined with an epistemic assumption: that knowledge objects can be freely taken for the purpose of scientific argument. A recurring theme in this dissertation is the way medical practitioners map their own beliefs onto the bodies of the sick, and that this mapping creates a terrain from which knowledge may be extracted from those same patients. I use a cartographic metaphor to point toward a colonial spatial ideology—cures are discovered, certain practitioners are pioneers, tuberculosis must be conquered.10 These implicit ideas of extraction and control are linked to the ways patients’ bodies are seen as resources in medical research (4.2.3). The bodies are seen as repositories of data, which may—and must—be excavated for their potential epistemic use. Johanna Drucker, in an essay on digital humanities critiques of the data sciences, writes,

Data pass themselves off as mere descriptions of a priori conditions. Rendering observation (the act of creating a statistical, empirical, or subjective account or image) as if it were the same as the phenomena observed collapses the critical distance between the phenomenal world and its interpretation, undoing the basis of interpretation on which humanistic knowledge production is based.11

To respond to this falsely ahistorical and apolitical frame of data, Drucker redefines the quantitative material drawn from natural sources as ‘capta’. Operating as a binary opposite of data,

Capta is ‘taken’ actively while data is assumed to be a ‘given’ able to be recorded and observed. From this distinction, a world of differences arises. Humanistic inquiry acknowledges the situated, partial, and constitutive character of knowledge production, the recognition that knowledge is constructed, taken, not simply given as a natural representation of pre-existing fact.12

This dissertation articulates the specimen as capta. The research objects that I use in this dissertation are stolen, staged, and deemed natural (0.1.4). There is more than a representational construction of the specimen, but also a naturalization of these research objects which severs them from the original patient’s histories, cultures, and identities.13 The specimen is always taken. It is always taken from someone.

In attending to these thefts, there becomes a need to address the various technologies of capture, preservation, and dissemination. The specimen as a media object is an intentionally broad category, attending to the various ways medical researchers ingest materials into their arguments. Media studies, and specifically film studies, has tended to rely on medicine’s use of cinematographic technologies. This means that disciplines like physiology have been examined in great detail,14 but others remain in need of continued scrutiny.15 The problem with these medium-first approaches is that they necessarily have to narrow the focus of the research: looking only for research that relied on filmic technologies.

By focusing on the specimen, I turn to look at the ways natural phenomena are made legible in scientific discourses (2.3.1). By shifting to focus on a research object found inside the body of a patient, I am able to shift what media studies can discuss in the production of scientific inquiry. By researching the specimen—which is often bespoke, unique to its construction, and informed by non-capitalized representational technologies—I am able to address a major gap in conversations between media studies and STS. The specimen lets me keep the patient, their life, and their remains in focus (2.4.3; 4.2.4). There are no specimens that can be made without someone’s body—a body that is separate from the doctor’s—which has been taken, brought into a scientific context, and framed to be legible. The person’s life, dying, and death is necessary data for the formulation of pathological knowledge (2.3.2); a person’s life, dying, and death enables the pathological phenomena to exist in the first place. The specimen is not just a change in focus, but one that demands new ethical framework (0.2.2; 4.2.3). These objects were people once. The transformation from patient, to research subject, to research object requires attention and care, which media studies in its focus on image, representation, and technologies of replication, has had difficulty conceptualizing.

-

Latour, Bruno, and Steve Woolgar. Laboratory Life: The Construction of Scientific Facts. 2nd ed. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1986; Hacking, Ian. The Social Construction of What. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2000; Shapin, Steven. Never Pure: Historical Studies of Science as If It Was Produced by People with Bodies, Situated in Time, Space, Culture, and Society, and Struggling for Credibility and Authority. Baltimore, Md: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010; TallBear, Kim. Native American DNA: Tribal Belonging and the False Promise of Genetic Science. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013. ↩

-

TallBear, Kim. Native American DNA: Tribal Belonging and the False Promise of Genetic Science. 11. ↩

-

Fields, Karen E., and Barbara J. Fields. Racecraft: The Soul of Inequality in American Life. London & New York: Verso, 2012. ↩

-

Washington, Harriet A. Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present. New York: Harlem Moon & Broadway Books, 2006; Willoughby, Christopher D. E. Masters of Health: Racial Science and Slavery in U.S. Medical Schools. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2022. ↩

-

I will often use the term “research” ahead of the terms “object” or “subject” to imply my interest in these terms use in academic inquiry. I am most interested in how researchers create subjects and objects, rather than thinking of these terms in broader, non-epistemic contexts. ↩

-

This approach to mediation is indebted to Lisa Gitelman, and, broadly, the media archaeological turn in media studies. This discourse focuses on non-dominant media forms to understand broader ideologies associated with technology and representation.

Gitelman, Lisa. Paper Knowledge: Toward a Media History of Documents. Duke University Press, 2014.

See also: Huhtamo, Erkki, and Jussi Parikka, eds. Media Archaeology: Approaches, Applications, and Implications. Berkeley, Los Angeles & London: University of California Press, 2011; Parikka, Jussi. What Is Media Archaeology? Cambridge: Polity, 2012; Ernst, Wolfgang. Digital Memory and the Archive. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2012. ↩

-

Latour, Bruno. We Have Never Been Modern. Translated by Catherine Porter. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1993. ↩

-

Hall, Stuart. “Encoding/Decoding.” In Media and Cultural Studies: Key Works, edited by Meenakshi Gigi Durham and Douglas M. Kellner, 163–73. Malden: Blackwell, 2006. 169. Italics by author. ↩

-

Curtis, Scott. “Photography and Medical Observation.” In The Educated Eye, edited by Nancy Anderson and Michael R. Dietrich, 68–93. Hanover: Dartmoth College Press, 2016. ↩

-

Latour, Bruno, and Steve Woolgar. Laboratory Life: The Construction of Scientific Facts. 2nd ed. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1986.

Michel Foucault also talks about how the colonial spatial dynamics drive geography. Foucault, Michel. “Questions on Geography.” In Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings 1972-1977, edited by Colin Gordon, translated by Colin Gordon, Leo Marshall, John Mepham, and Kate Soper, 63–67. New York: Vintage Books, 1980.

There is also a great example of how war-like metaphors can drive research projects into disease, specifically cancer research. Mukherjee, Siddhartha. The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of Cancer. New York: Scribner, 2010. ↩

-

Drucker, Johanna. “Humanities Approaches to Graphical Display.” Digital Humanities Quarterly 5, no. 1 (2011). ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

The problem is that because bodies were stolen in many cases, there was a need to obscure from where the materials were drawn.

Warner, John Harley. “The Aesthetic Grounding Of Modern Medicine.” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 88, no. 1 (Spring 2014): 1–47. ↩

-

Cartwright, Lisa. Screening the Body: Tracing Medicine’s Visual Culture. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1995; Curtis, Scott. The Shape of Spectatorship: Art, Science, and Early Cinema in Germany. New York: Columbia University Press, 2015. ↩

-

A good example of how this limitation causes problems for media studies scholars, is in Hannah Landecker’s otherwise exceptional work on microcinematography. She overdetermines the moving image’s transformative qualities in microscopic imaging, writing, “[t]he cellular film, an infinitely reproducible inscription of a continuous living movement rather than a set of histological stills, was a new form of narrative as well as a new set of aesthetic forms for both scientist and layman.” The problem is that while microcinematography was, indeed, novel, so was histology and histochemistry (2.1.3)

Landecker, Hannah. “Cellular Features: Microcinematography and Film Theory.” Critical Inquiry 31 (2005): 912-13. ↩