Introduction

Specimen Studies

0.1.1 | 0.1.2 | 0.1.3 | 0.1.4 | 0.1.5Methods

0.2.1 | 0.2.2The Structure of this Dissertation

0.3.1Tuberculosis' Visual Culture

Visual Practices in Medical Culture

1.1.1 | 1.1.2 | 1.1.3Seeing and Settling in the Sanatorium Movement

1.2.1 | 1.2.2 | 1.2.3 | 1.2.4 | 1.2.5Teaching Public Health

1.3.1 | 1.3.2 | 1.3.3 | 1.3.4 | 1.3.5Representing Doctors in Tuberculous Contexts

1.4.1 | 1.4.2Using Human Specimens in the Study of Tuberculosis

Seeing Disease in Methyl Violet

2.1.1 | 2.1.2 | 2.1.3 | 2.1.4Case Histories

2.2.1 | 2.2.2 | 2.2.3 | 2.2.4Visceral Processes

2.3.1 | 2.3.2Relation

2.4.1 | 2.4.2 | 2.4.3Arts-Based Inquiry

Introduction

3.1.1 | 3.1.2 | 3.1.3 | 3.1.4Terminal Imaginaries & Tuberculous Imaginaries

3.2.1 | 3.2.2 | 3.2.3 | 3.2.4 | 3.2.5 | 3.2.6Dermographic Opacities

3.3.1 | 3.3.2 | 3.3.3 | 3.3.4Tactical Pretensions

3.4.1 | 3.4.2 | 3.4.3Designing Opacity

A Shift towards the Anticolonial

4.1.1 | 4.1.2 | 4.1.3 | 4.1.4Refusals and Opacities

4.2.1 | 4.2.2 | 4.2.3 | 4.2.4Digital and Ethical Workflows

4.3.1 | 4.3.2 | 4.3.3 | 4.3.4 | 4.3.5Conclusion

4.4.1Coda

Prometheus Undone

5.1.1 | 5.1.2 | 5.1.3 | 5.1.4Appendix

The Tuberculosis Corpus

X.1.1 | X.1.2 | X.1.3Web Design

X.2.1 | X.2.2 | X.2.3 | X.2.4Installation Materials

X.3.1 | X.3.2 | X.3.3Index

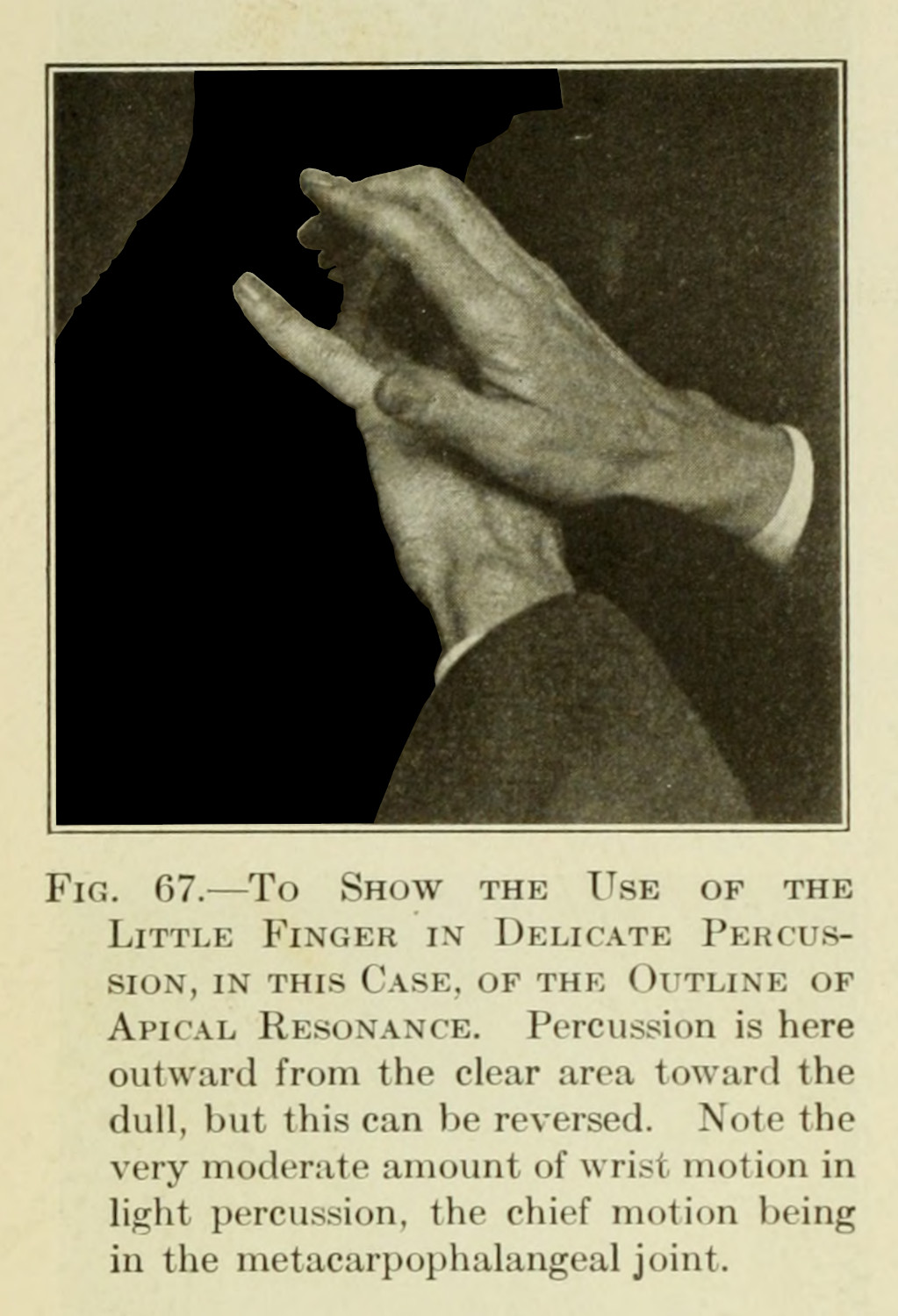

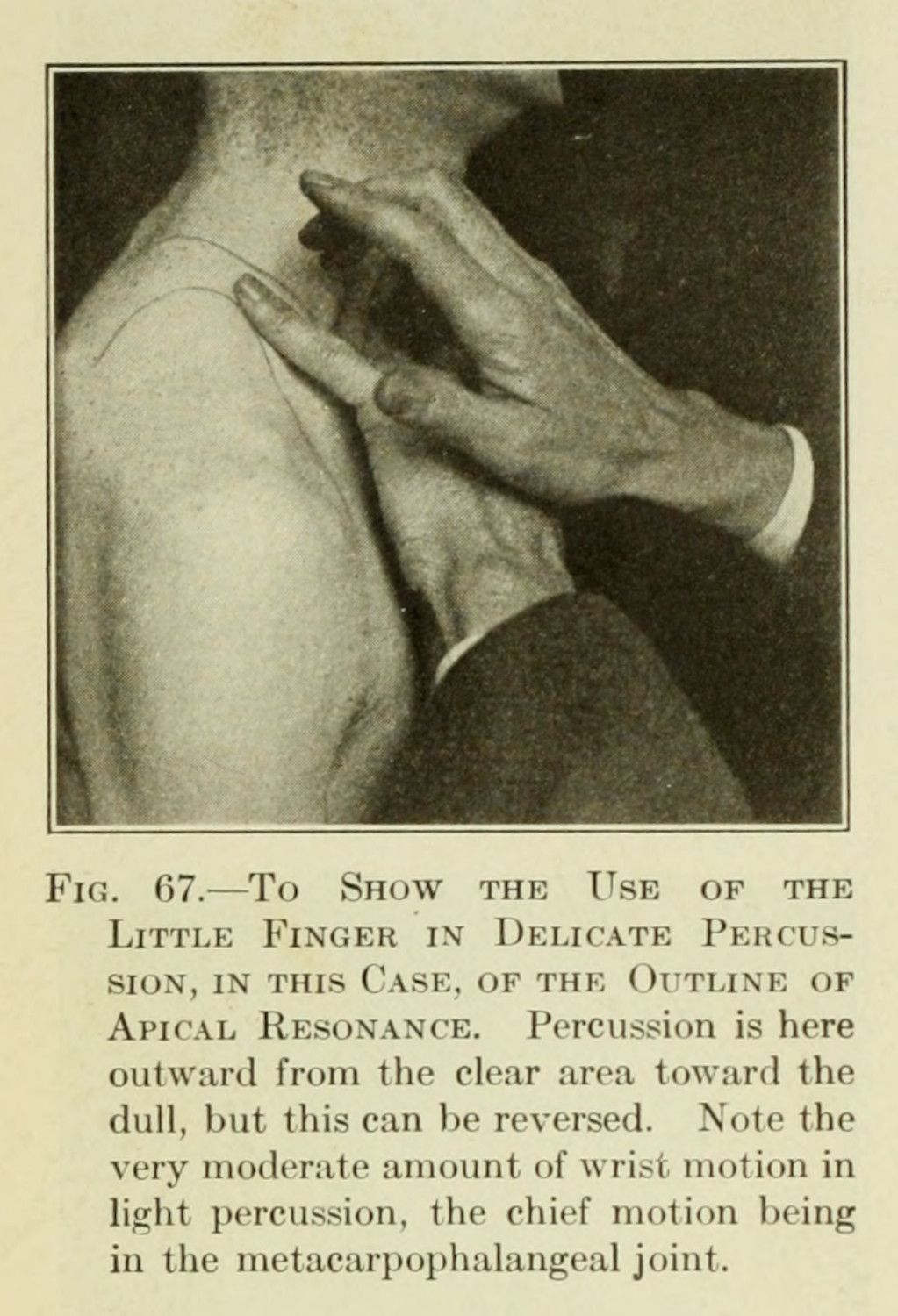

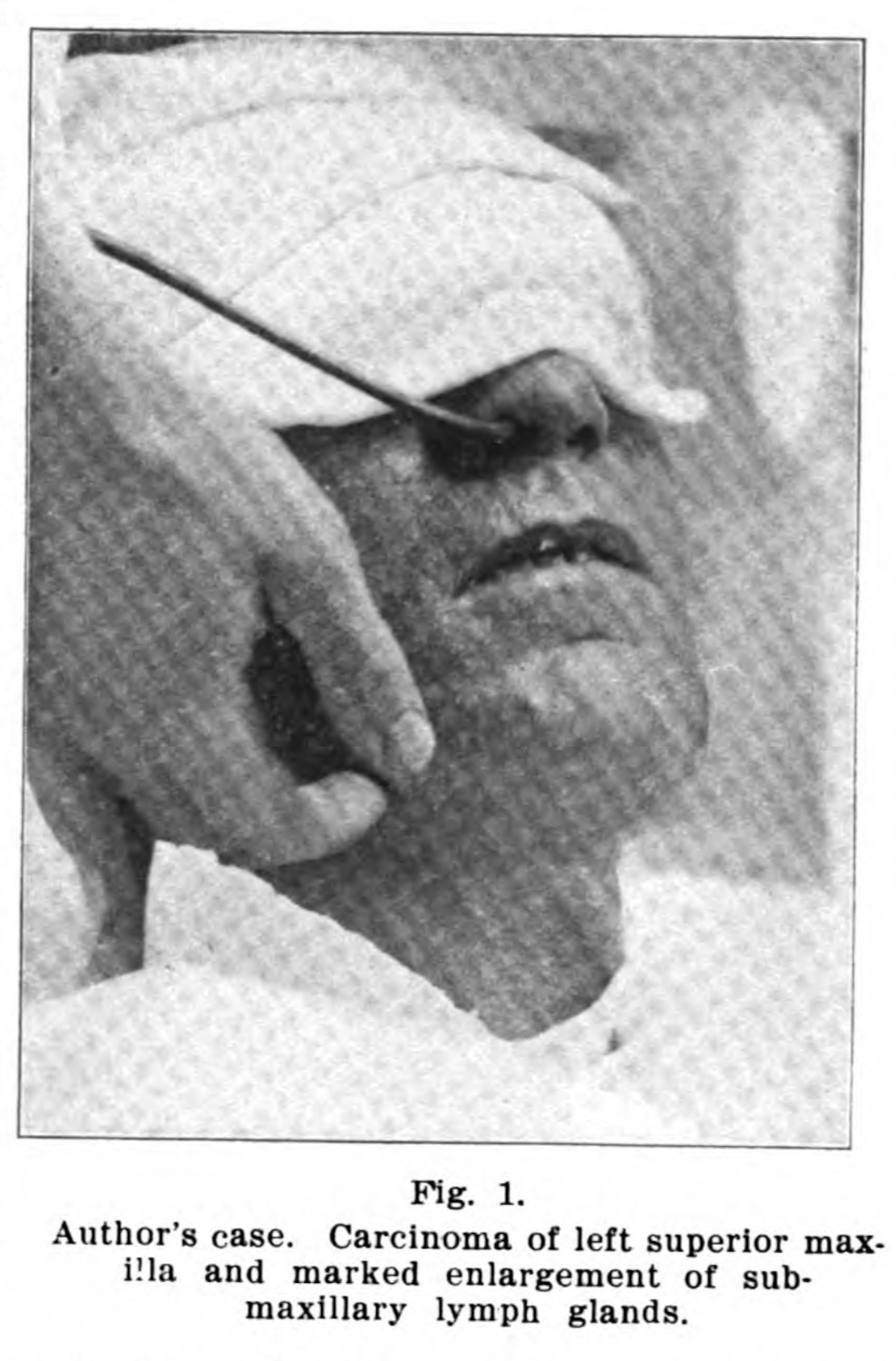

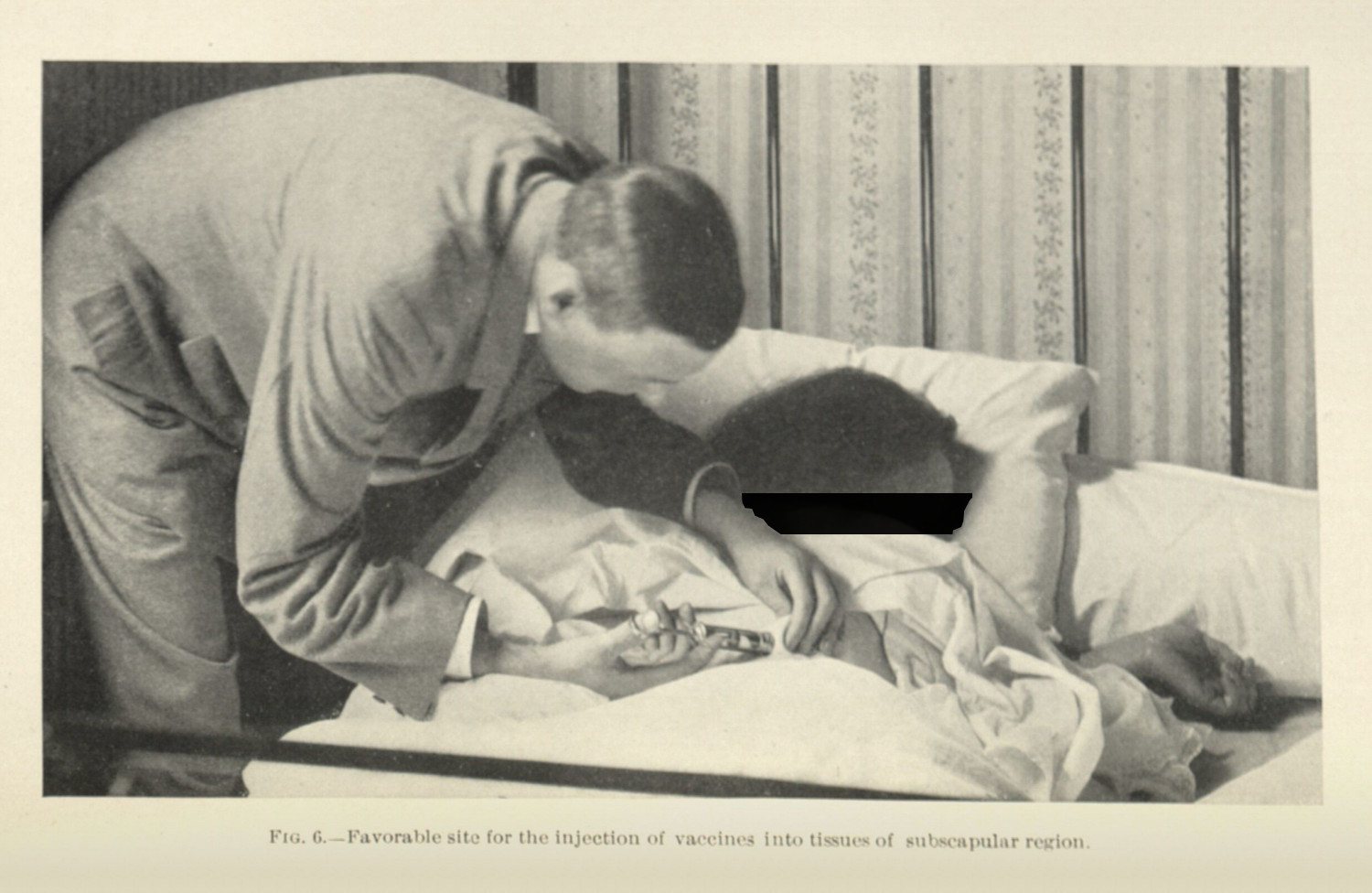

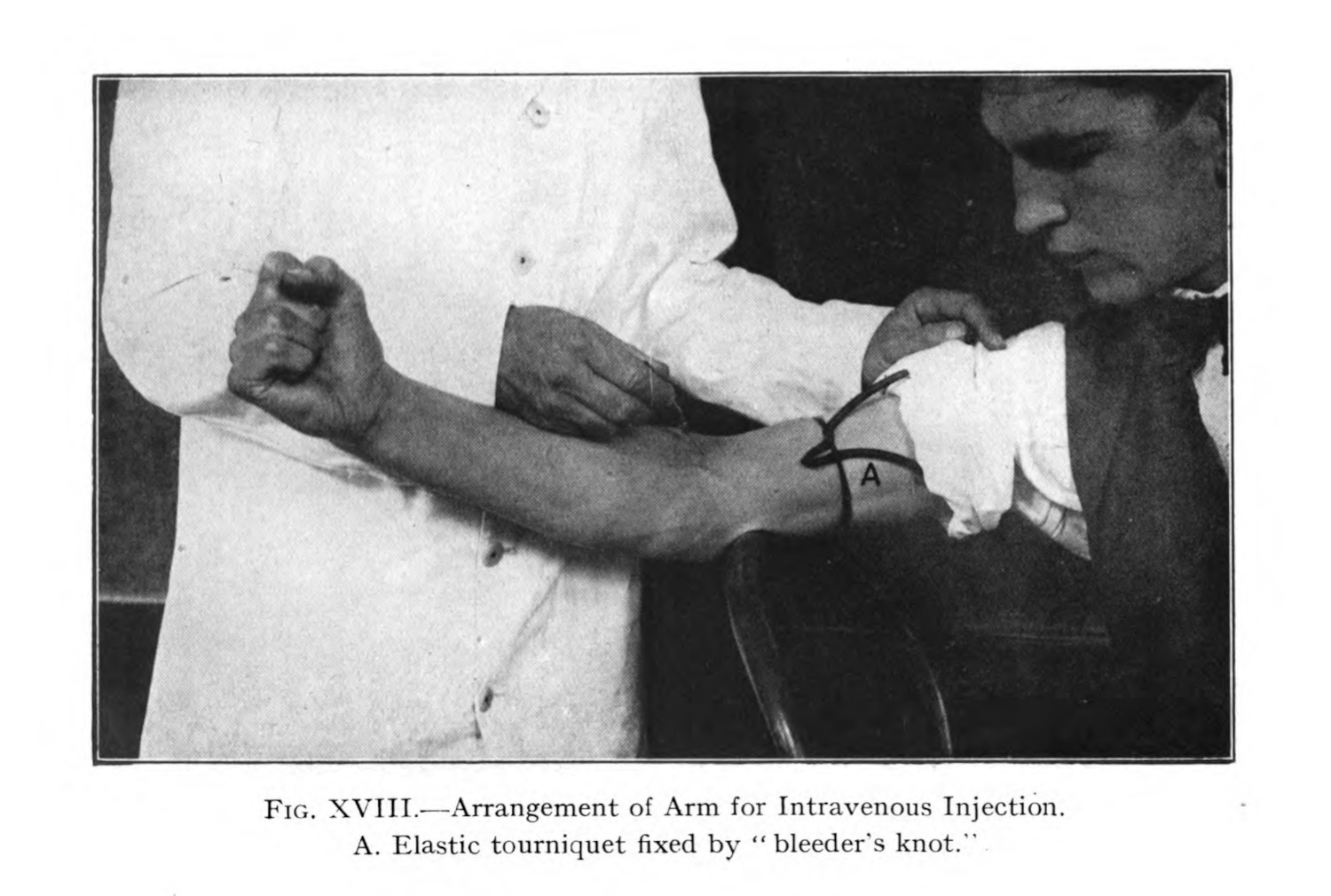

Doctor’s hands are important for their work: they are used to hold patients in place, to percussively tap on their chest to hear for tuberculous infection in the lungs (fig. 2), they are used in surgery, in autopsy. The tuberculosis corpus has plenty examples of images showing doctors how to use their hands (figs. 1 & 2).

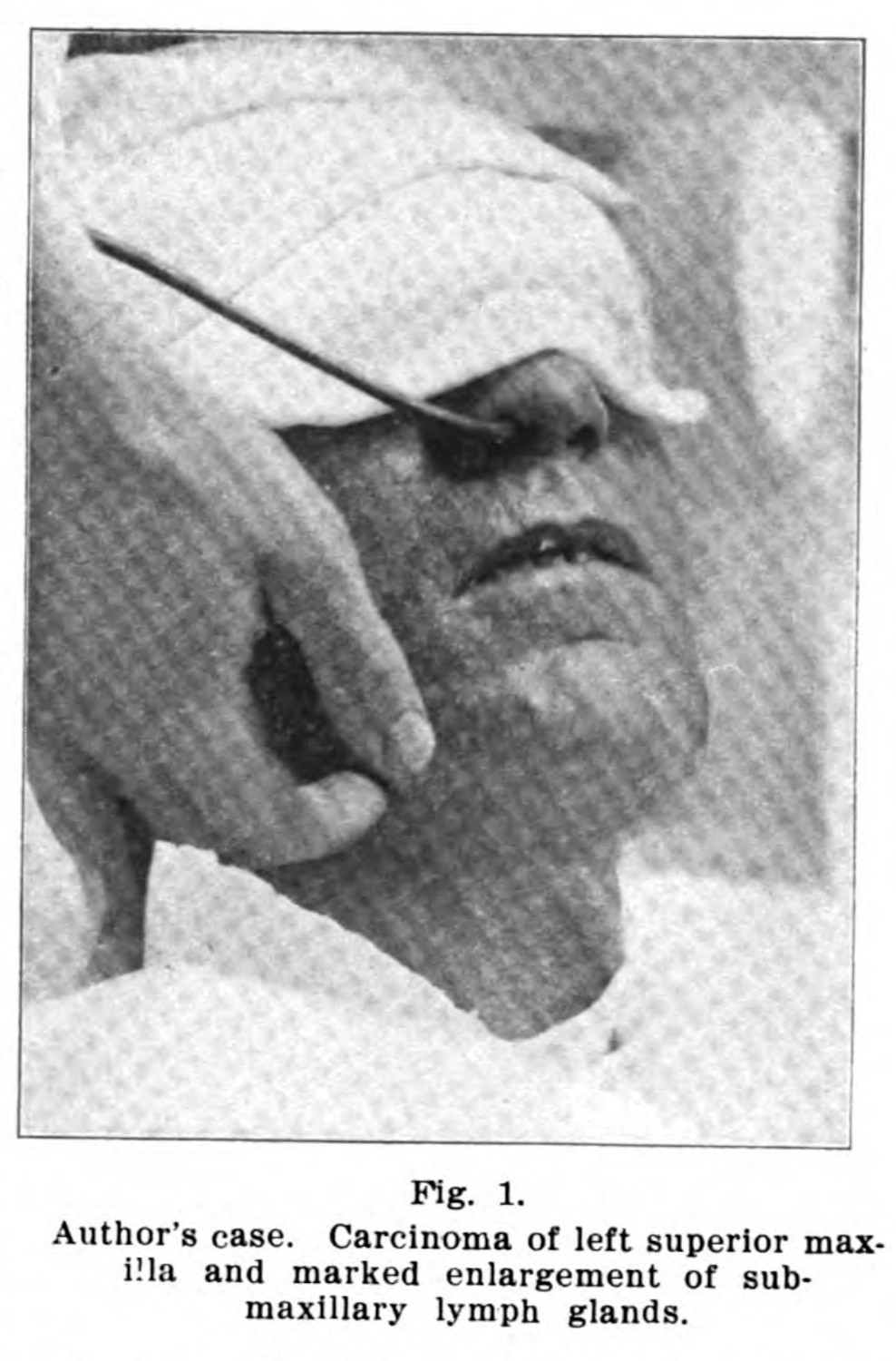

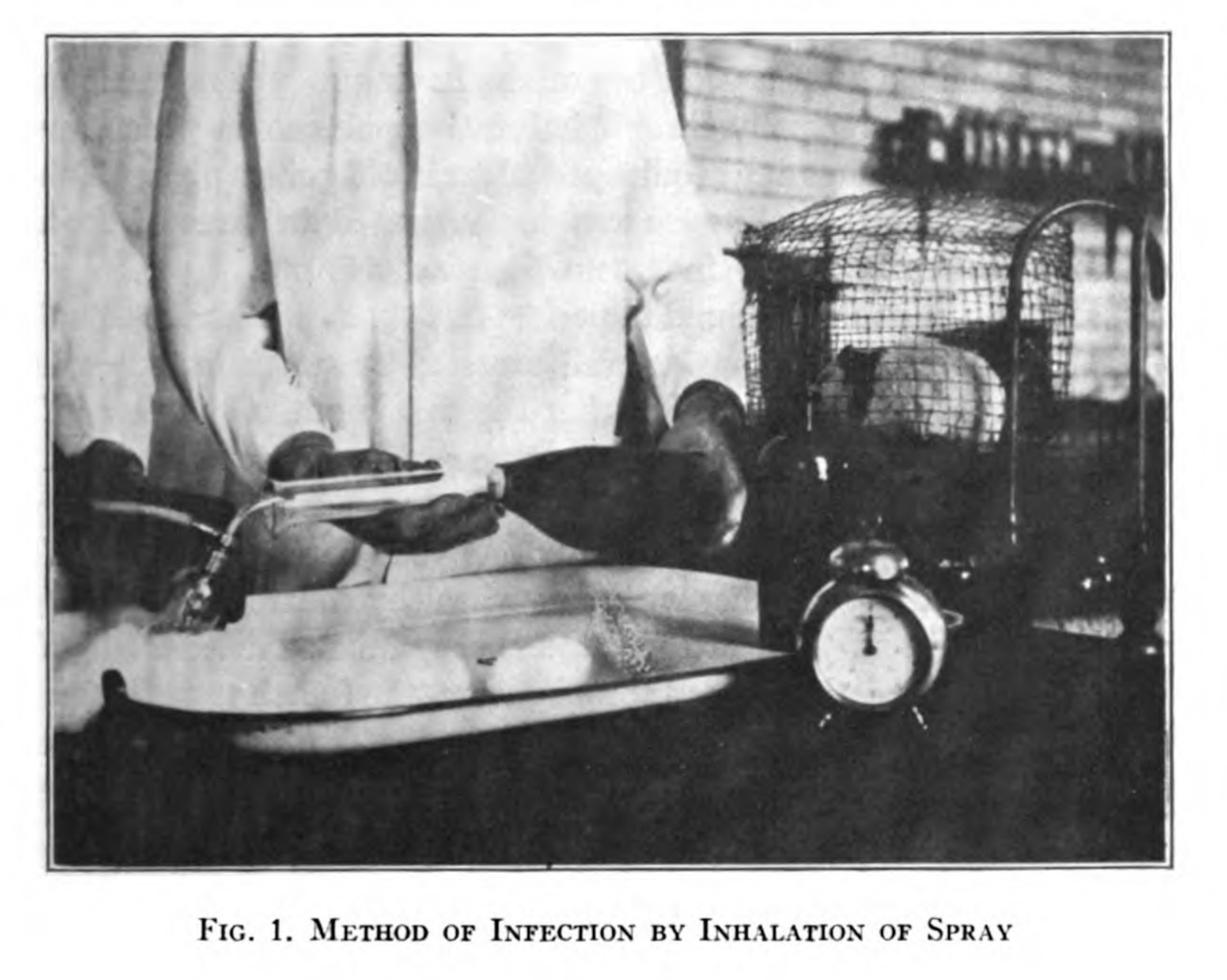

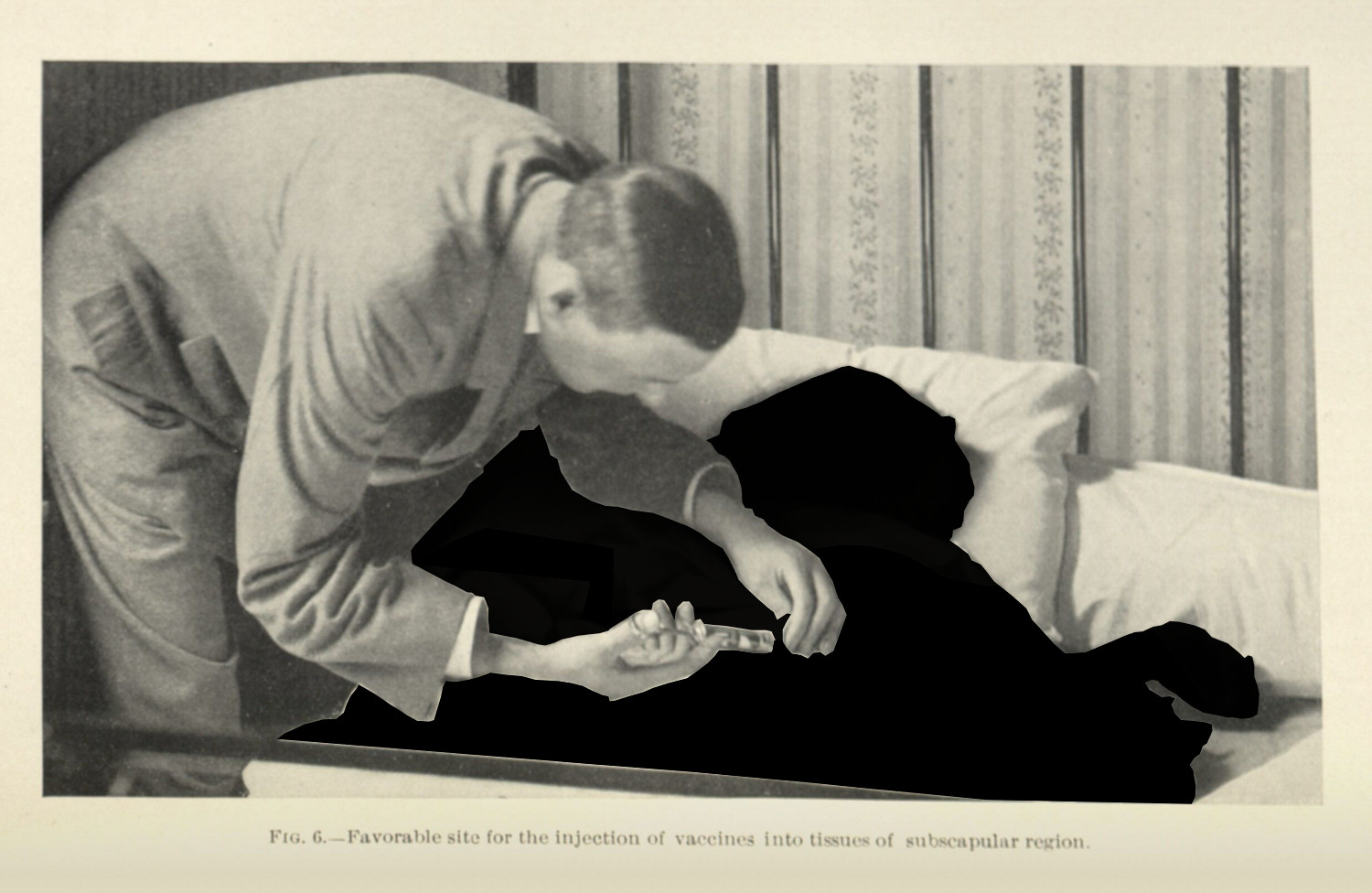

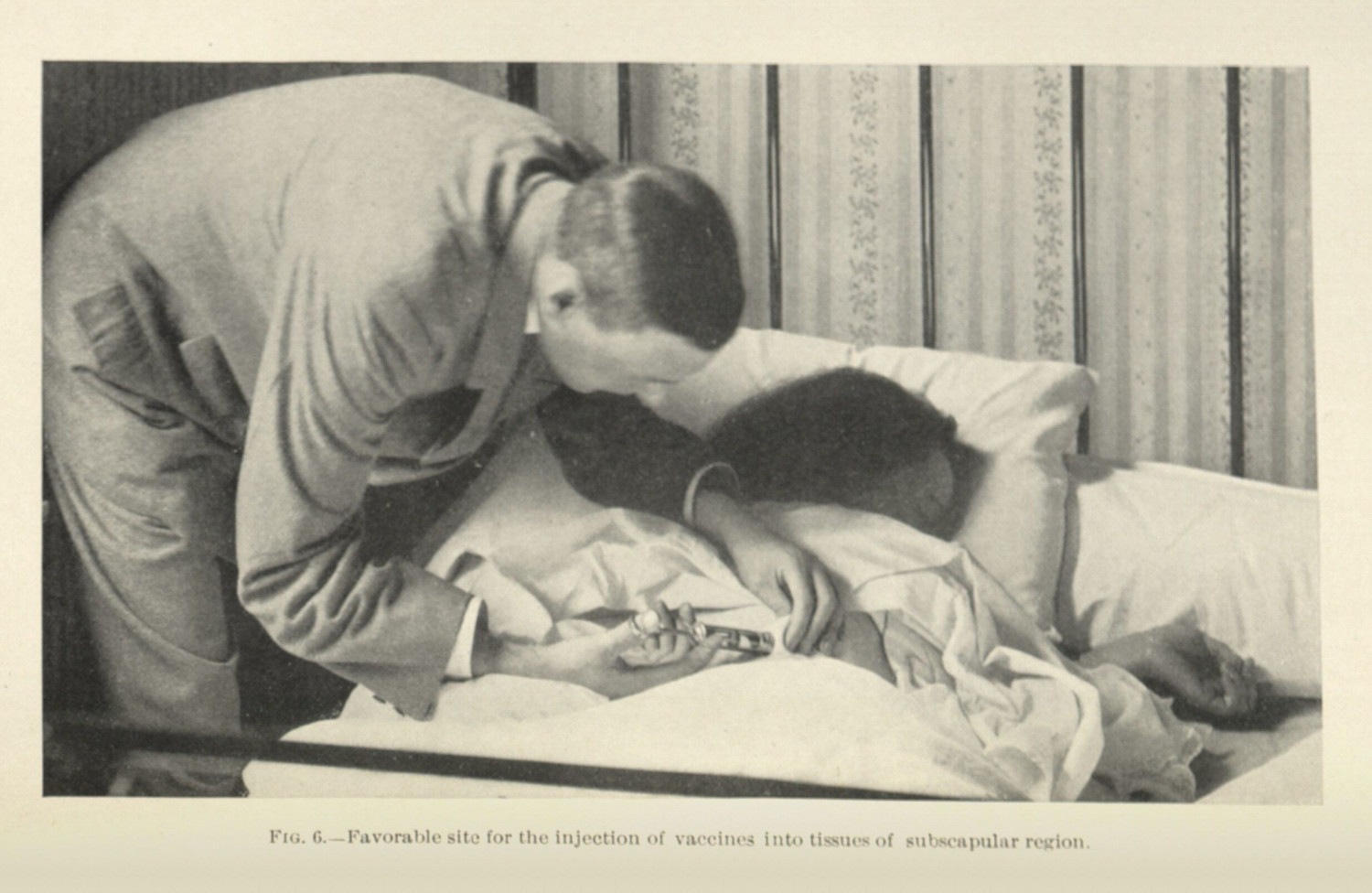

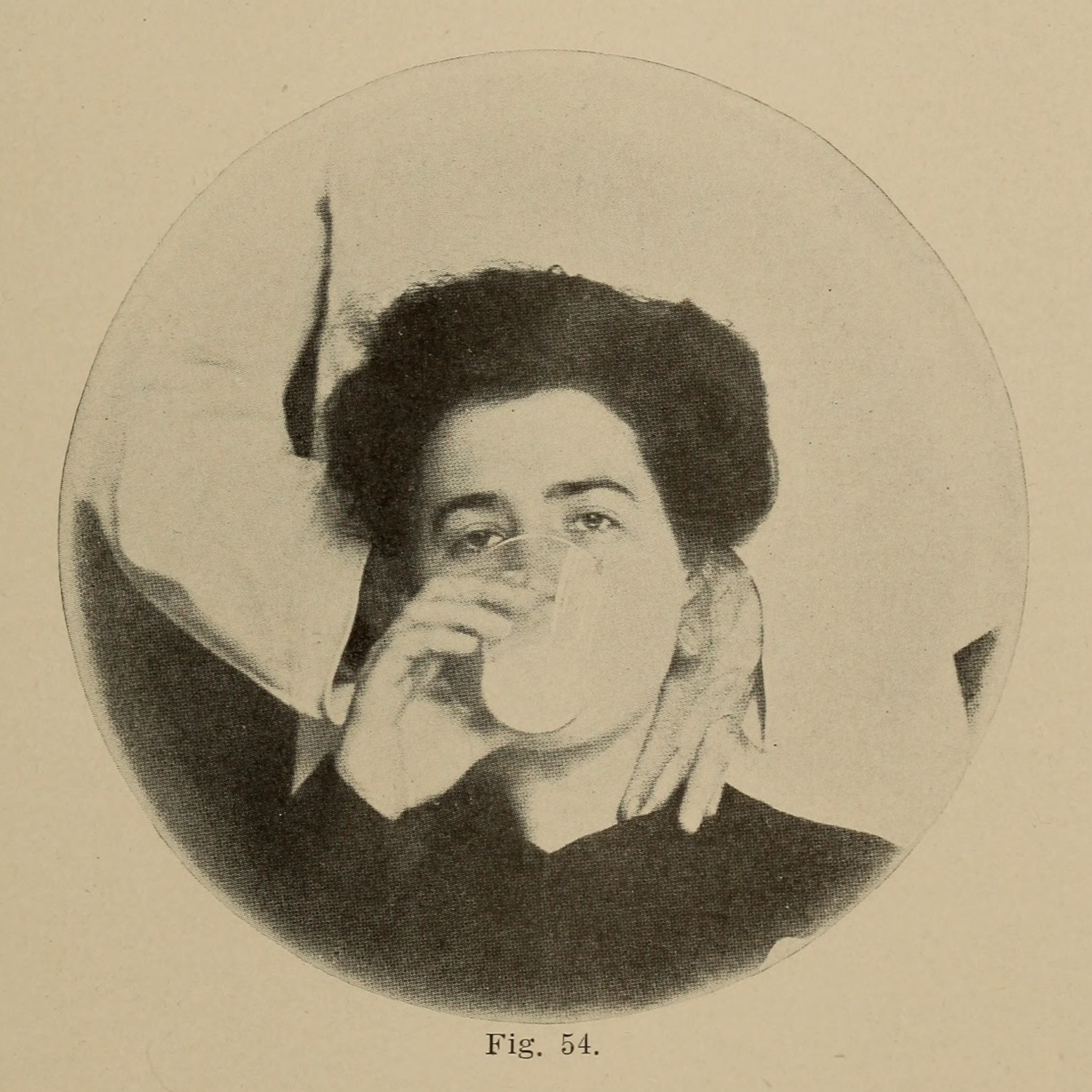

Doctors’ hands appear more often in specimen photographs, than doctors do in the professionally framed photographs discussed in the previous section (1.4.1). Doctors reach out to display a diagnostic procedure (fig. 1); their hands work with experimental instruments (fig. 3). In some photographs the doctor’s hands may be necessary to display the proper way to go about a complicated procedure (fig. 4 - 6). The thing that unifies these later images is that the doctors’ hands emerge in the context of a different kind of biomedical visual practice: when there is a specific research object that needs to be seen on another human’s body.

So far in this chapter, I have avoided images that depict specimens. What I have shown is that the contexts and discourses around medical visual culture is much messier and broader than Michel Foucault could articulate. For this dissertation, these doctors’ hands serve as a bridge: to link these other visual cultures to the visualities of the specimen, which will appear in the next chapter (2.1.4; 2.2.2). They reveal a kind of construction and specificity in framing—to hold a patient still, to bring the camera to the patient or the patient to the camera, to have another pair of hands operate the machine—as well as an intention, to grasp both in an intellectual sense but also in a domineering one.1

What is important, and what I see when I see doctors holding their patients in this way, is a striking contrast: while these images share an inkling of intent as the ones discussed in the previous subsection (1.4.1), their composition is decidedly different. Where doctors and their patients are gazed at a distance in examples of doctors at work, the point of view in these accidental hands in frame is always much closer to the humans with the shot sizes ranging from a medium-close to a close-up. This is partly because of the image’s intended object: the photographer is trying to capture something smaller than a whole human body. The reduction in scope—from whole room to a part of the body—is matched by the amount of space that can be taken up by the doctor: it is a scale of hands, not of bodies. And the hands in frame are not always the intended object of interest; they are an unintentional side effect of a discipling practice (2.1.2). They hold patients in place. They make the phenomena visible. They turn the patient, the body, the organ, the subject, the object, whatever the intended imaging target, docile.2 I will address these ideas in more detail in the next chapter (2.1.3; 2.1.4; 2.3.1).

There is power expressed in this imaging practice—who is imaged and who is left out of the frame; who controls the image and who is imaged. Some spaces are deemed clean and others dirty, some bodies are allowed rest and care and others are placed within a disciplining framework, where they are always st fault (1.3.4; 1.3.5).3 These contrasts remain ever present in the discourse, born on tide of supposed superiority: by who cures and who is cured, by who researches and who is researched, by who has scientific/social/cultural authority and who does not (0.1.4; 2.1.4; 2.4.2).4

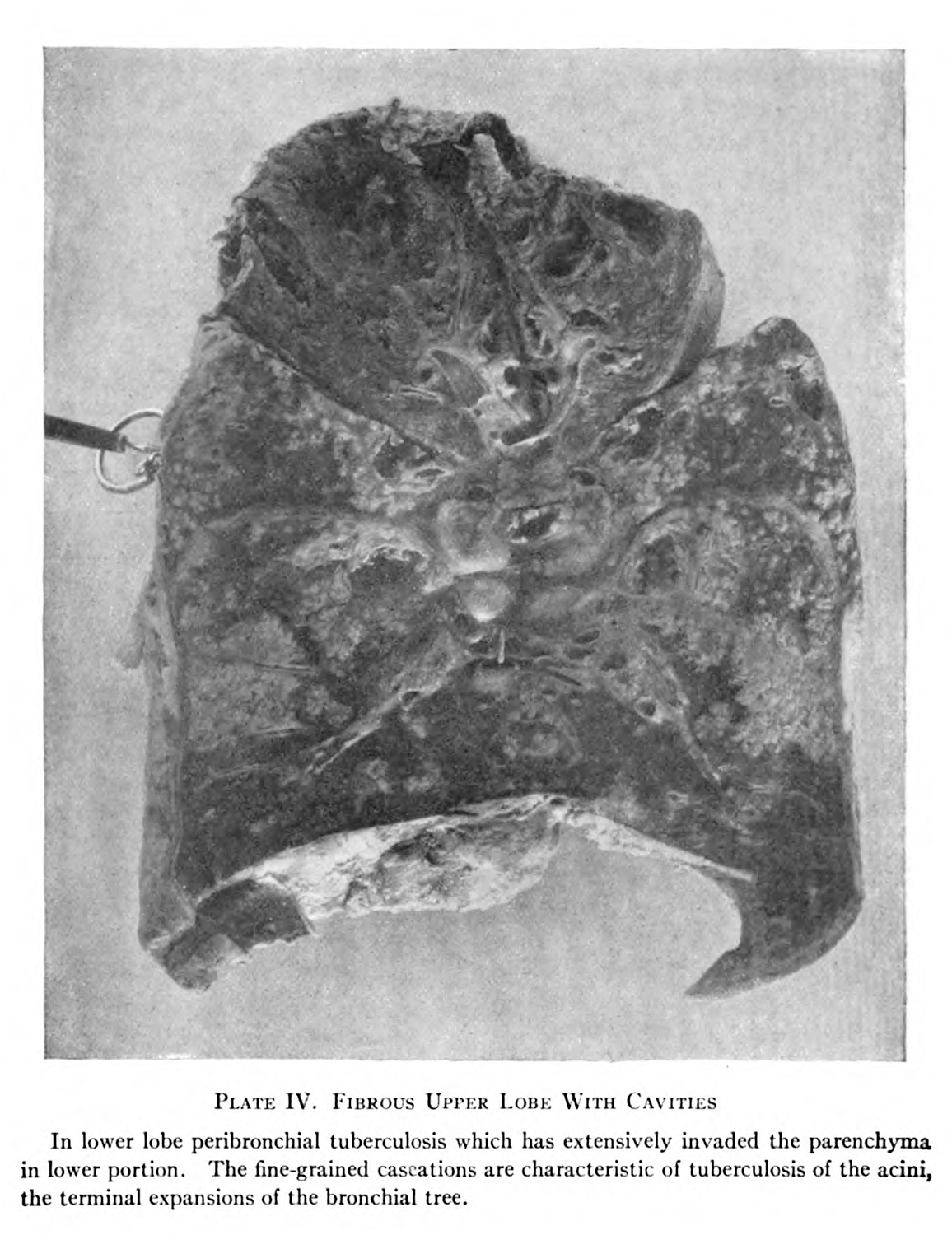

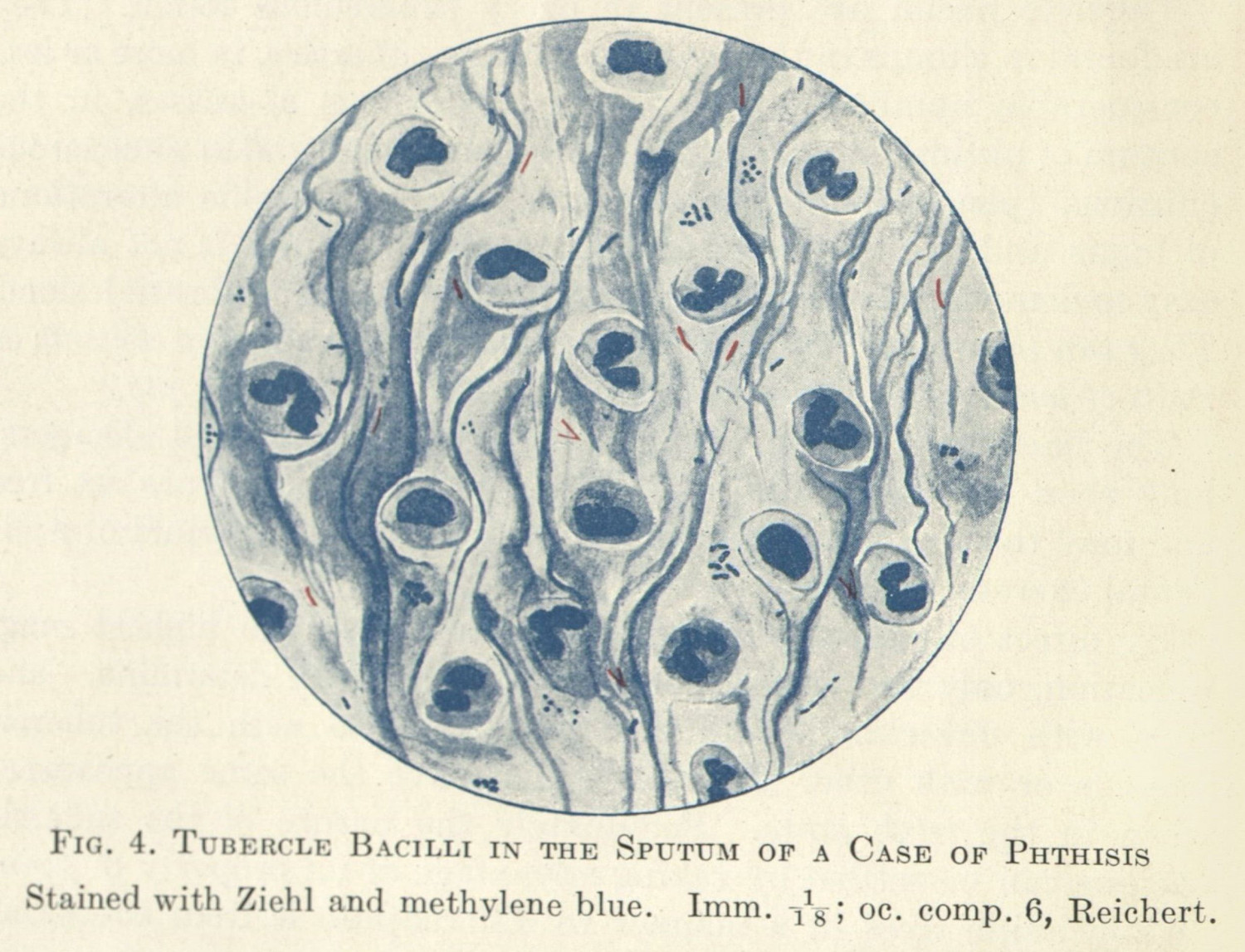

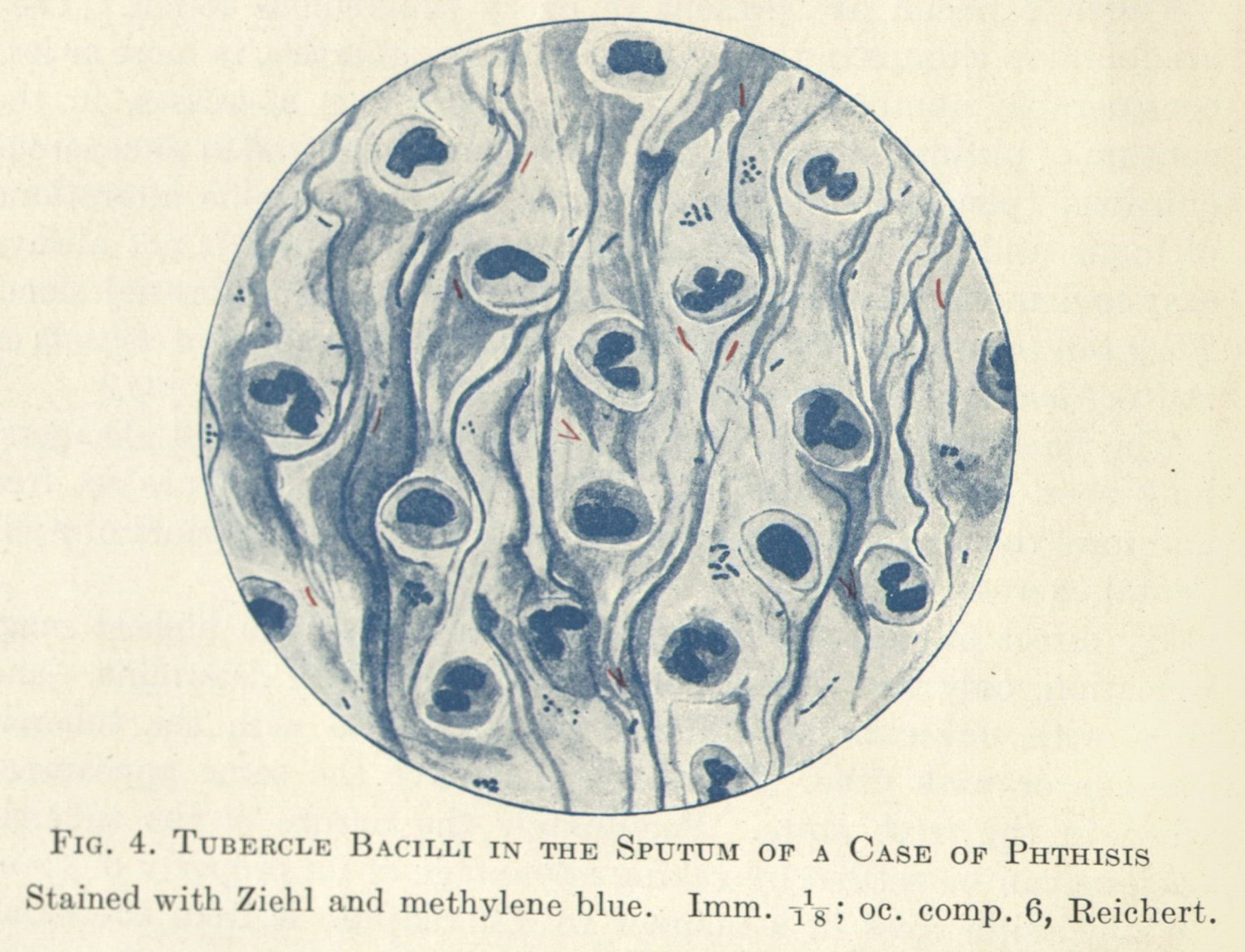

In the next chapter, I am going to look at the human body as it has been pieced apart—through magnification, through the dissection of organs. All of these images were been taken from the bodies of research subjects for the purpose of scientific research. The doctors’ hands will be absent, but their intention will not be. Sometimes doctors’ intervention will be more apparent, like the use of a pin that pulls a flap of flesh to reveal what is underneath (fig. 7), and sometimes this will be less obvious, as the doctors dye cells of patients (fig. 8) (2.1.3). These processes follow a different kind of vision, one which is trained in doctors, but which rhymes5 with and engages in concert with the kinds of visual practices described in this chapter. While not dependent, the two are entangled in such a way so as it would do harm to pull them apart fully.6

-

Glissant, Édouard. Poetics of Relation. Translated by Betsy Wing. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1997. 189-94. ↩

-

Curtis, Scott. The Shape of Spectatorship: Art, Science, and Early Cinema in Germany. New York: Columbia University Press, 2015.

I will address this in more detail in the next chapter. ↩

-

Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. New York: Vintage Books, 1995. ↩

-

Nested further, too, are the entanglements of race, class, ability, gender, and sexuality. ↩

-

Takemoto, Tina. “Open Wounds.” In Thinking Through the Skin, edited by Sarah Ahmed and Jackie Stacey, 104–23. London: Routledge, 2001. ↩

-

Kittler, Friedrich A. Discourse Networks 1800 / 1900. Translated by Michael Metteer and Chris Cullens. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1990; Ernst, Wolfgang. Digital Memory and the Archive. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2012; Huhtamo, Erkki, and Jussi Parikka, eds. Media Archaeology: Approaches, Applications, and Implications. Berkeley, Los Angeles & London: University of California Press, 2011; Parikka, Jussi. What Is Media Archaeology? Cambridge: Polity, 2012. ↩