Introduction

Specimen Studies

0.1.1 | 0.1.2 | 0.1.3 | 0.1.4 | 0.1.5Methods

0.2.1 | 0.2.2The Structure of this Dissertation

0.3.1Tuberculosis' Visual Culture

Visual Practices in Medical Culture

1.1.1 | 1.1.2 | 1.1.3Seeing and Settling in the Sanatorium Movement

1.2.1 | 1.2.2 | 1.2.3 | 1.2.4 | 1.2.5Teaching Public Health

1.3.1 | 1.3.2 | 1.3.3 | 1.3.4 | 1.3.5Representing Doctors in Tuberculous Contexts

1.4.1 | 1.4.2Using Human Specimens in the Study of Tuberculosis

Seeing Disease in Methyl Violet

2.1.1 | 2.1.2 | 2.1.3 | 2.1.4Case Histories

2.2.1 | 2.2.2 | 2.2.3 | 2.2.4Visceral Processes

2.3.1 | 2.3.2Relation

2.4.1 | 2.4.2 | 2.4.3Arts-Based Inquiry

Introduction

3.1.1 | 3.1.2 | 3.1.3 | 3.1.4Terminal Imaginaries & Tuberculous Imaginaries

3.2.1 | 3.2.2 | 3.2.3 | 3.2.4 | 3.2.5 | 3.2.6Dermographic Opacities

3.3.1 | 3.3.2 | 3.3.3 | 3.3.4Tactical Pretensions

3.4.1 | 3.4.2 | 3.4.3Designing Opacity

A Shift towards the Anticolonial

4.1.1 | 4.1.2 | 4.1.3 | 4.1.4Refusals and Opacities

4.2.1 | 4.2.2 | 4.2.3 | 4.2.4Digital and Ethical Workflows

4.3.1 | 4.3.2 | 4.3.3 | 4.3.4 | 4.3.5Conclusion

4.4.1Coda

Prometheus Undone

5.1.1 | 5.1.2 | 5.1.3 | 5.1.4Appendix

The Tuberculosis Corpus

X.1.1 | X.1.2 | X.1.3Web Design

X.2.1 | X.2.2 | X.2.3 | X.2.4Installation Materials

X.3.1 | X.3.2 | X.3.3Index

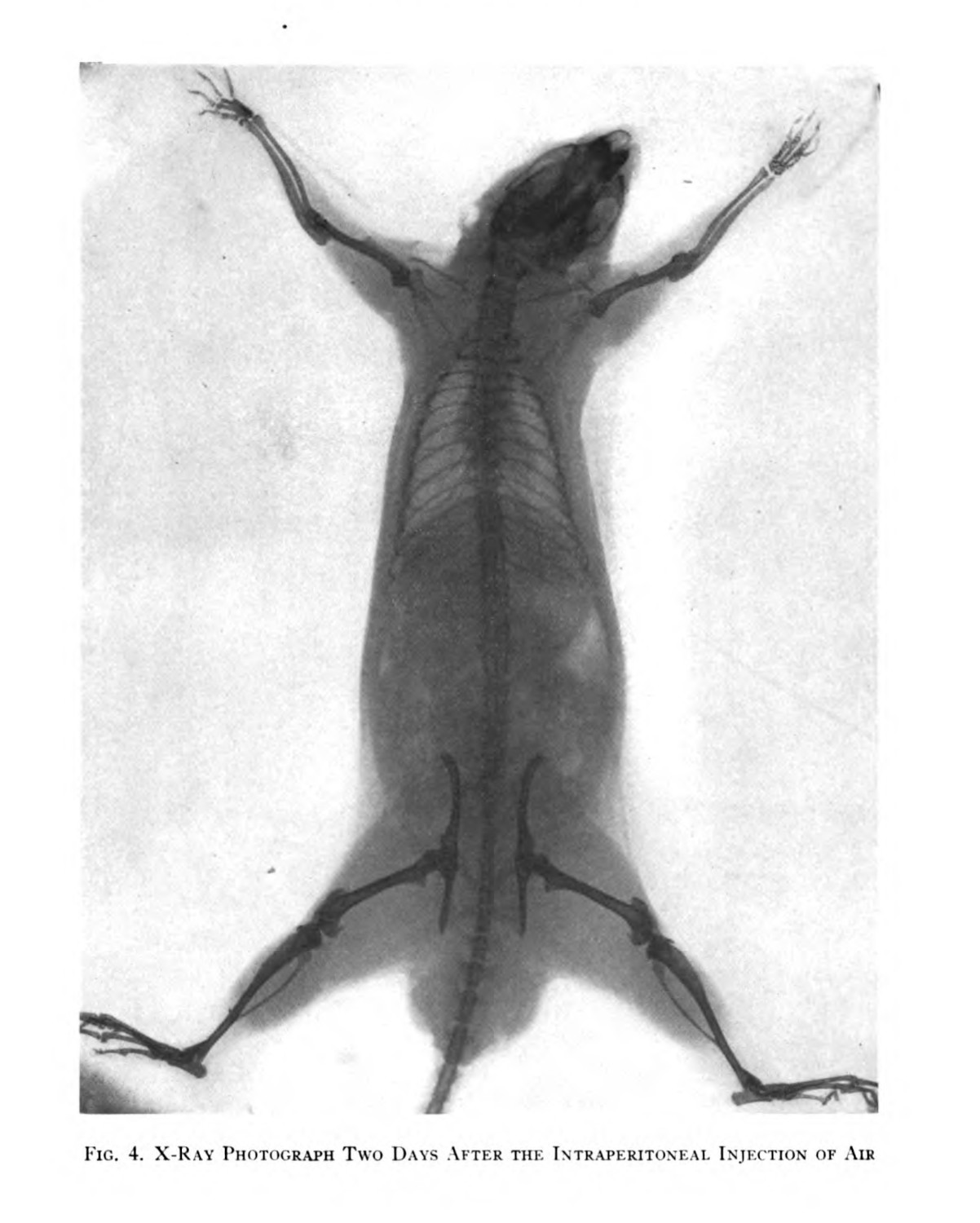

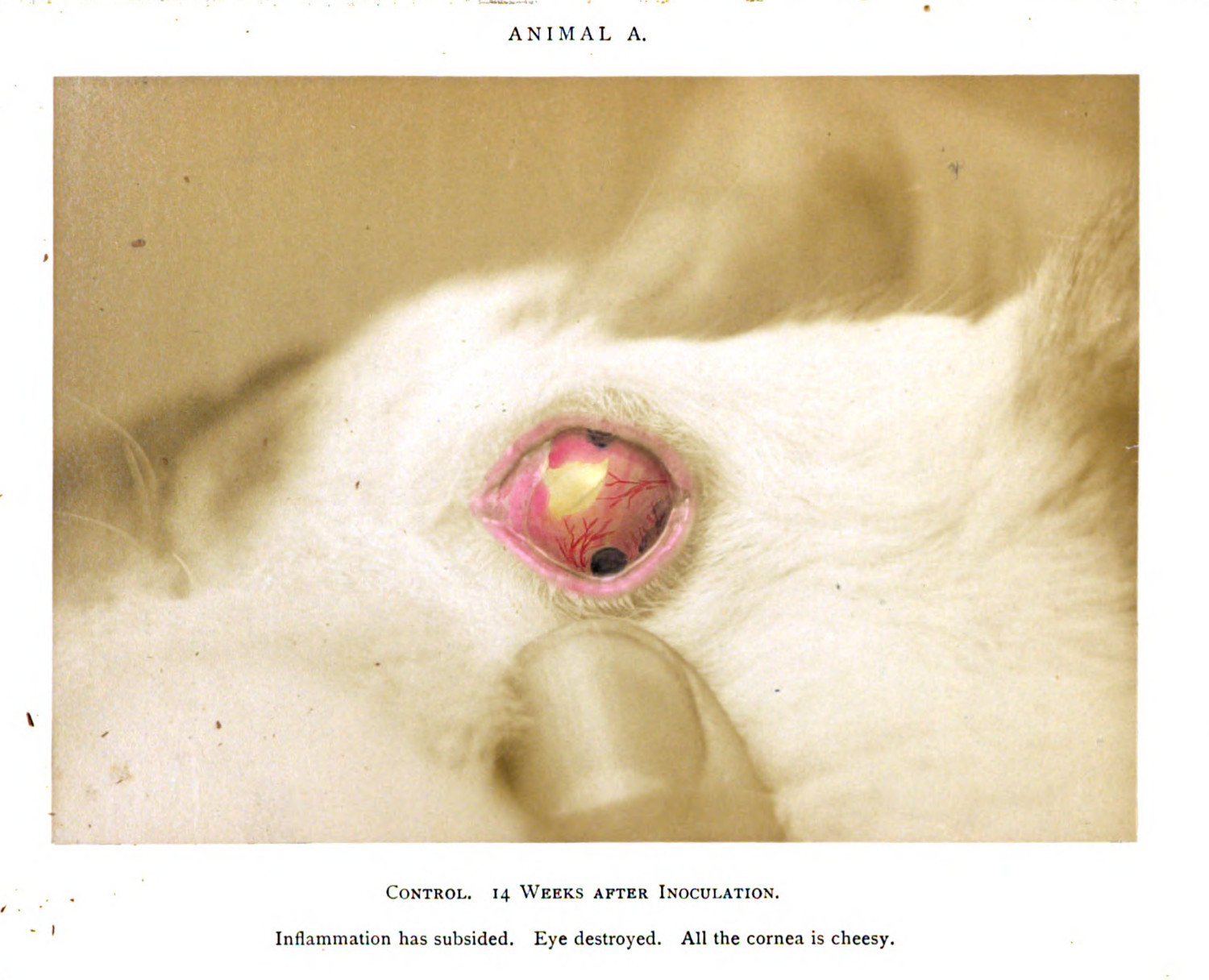

There are a lot of dead rabbits, and other animals, in the tuberculosis corpus and image data set (figs. 1 & 2) (X.1.1; X.1.3). Robert Koch’s bacteriological studies depended on a certain relationship between scientist and animal research subject, one which saw the living interface of an animal—guinea pigs for Koch, and rabbits for Edward Livingston Trudeau and H. J Corper, among others1—as an incubator for bacteriological processes (figs. 1 & 2). Their bodies could be used for various forms of experimentation, and their remains could be the space of examination, reflection, and distillation of phenomena.2 Koch’s relationship with them is from a perspective of researcher and their object (0.1.4), controlling these animals’ life and death for the purpose of scientific argument.

I begin this chapter with this case study as a concrete, but non-human, example of the kind of relationship which I will describe later in this chapter. This chapter stresses the material, embodied continuity between the research subject and the phenomenon which is represented in a specimen. More than a culturally constructed conception of vision (1.1.2), my interest is on the interdependencies which produce science’s viewable objects (0.1.4).

I stress Koch’s animal testing as a shorthand to consider medical science’s necroepistemic dependencies. I use the term necroepistemic3 to conjoin the implicit deathmaking technologies assumed in Achille Mbembe’s necropolitics,4 with the sociotechnological construction of the corpse in medical contexts (2.2.4), as well as western espistemics’ extractivist modes of knowledge creation (4.1.3). I will use the next sections to delineate necropolitics more fully. What matters for my analysis of Koch was the way death was a necessary, productive process for his research agenda.

Jill Casid describes how carceral, colonial, white supremacist capitalism produces death in ways that benefits itself: the obliteration of cultures, species, bodies, histories is all a productive part of its all-consuming expansionism. “Undoing” is not just a means of making die, so much as a way to make die and reform again, and Casid sees this process as one of potential intervention.5 For extractivist colonial epistemics, the production of death also produces inert forms, forms that are simple enough to examine and define. Arguing for scholars to consider the necropolitical valences of knowledge systems, Ege Selin Islekel argues that it is necessary for scholars “to discuss not only the knowledge of necropolitics, but also the knowledge produced in necropolitics.”6 Where Islekel’s work posits the ways knowledge work constructs and produces forms of memory—which they articulate as “necro-epistemic methods”—I want to expand this framework to consider how death is productive for capitalistic and colonialist systems: these systems do not just produce dead subjects, but those subjects in life, during their dying and after death, are viewed as valuable for knowledge workers (2.2.4). This follows Harriet Washington’s observations about the treatment and exploitation of Black communities in the history of medicine: a sick population was useful to develop remedies for the ruling whites in America’s racial hierarchy (1.3.5).7 Building on Casid and Islekel’s ideas, the necroepistemics I apply in this chapter think about the advantages death affords for biomedical research: the production of death is also the production of potential research objects.

For Koch’s research, deathmaking is a necessary step. The guinea pig’s corpse provides proof or absence of the tuberculosis infection, which can then be mined again for subsequent injections, autopsies, and microscopic investigations (2.1.2). It is a necroepistemic relation because the experiment depends on the subject in life and the subject after death, and that the extraction of material after death is necessary for academic argument (2.2.4).

The specimens that the rest of this chapter will examine are known as wet tissue specimens. They are organs preserved in spirit—most likely a formalin mixture—and staged in such a manner as to be visible for a scientific observer to see and recognize an anatomical or pathological feature (1.1.2; 2.2.2). It is likely that every specimen procured in this chapter was taken at autopsy, and given that this period precedes informed consent (0.1.4),8 they probably were stolen against the wishes of the original patient, their families, or their communities.

Medicine’s visual culture is materially dependent on the bodies of its research subjects. Slipping between visual culture analysis and new materialist approaches to research, my desire is to keep the original patient in full view, and denote how dependent medical epistemics are on the patient.

-

Trudeau notes that the specific temperatures required to raise guinea pigs was a limitation for his research into the disease in Saranac Lake.

Trudeau, Edward Livingston. An Autobiography. Garden City & New York: Doubleday, Doran & Company, Inc., 1944. 201-230. ↩

-

My own research runs in parallel to the anti-vivisection movement in the United Kingdom and the United States. That is beyond the scope of this present study.

Lederer, Susan. Subjected to Science: Human Experimentation in America before the Second World War. Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995. ↩

-

The term necroepistemic has been coined very recently in postcolonial scholarship. Often these works develop the term “necroepistemics” in relation to Franz Fanon’s critical scholarship and Achille Mbembe’ necropolitics (2.2.4). These essays describe at different levels the production of knowledge and its connection to differing forms of death.

Abebe, Surafel Wondimu. “Left Ruins in Ethiopia: Imagining Otherwise Amid Necroepistemic Historiography.” Pmietnik Teatralny 70, no. 4 (2021): 161–82; Spragins, Elizabeth. A Grammar of the Corpse: Necroepistemology in the Early Modern Mediterranean. New York: Fordham University Press, 2023; Islekel, Ege Selin. “Nightmare Knowledges: Epistemologies of Disappearance.” In Turkey’s Necropolitical Laboratory: Democracy, Violence and Resistance, edited by Banu Bargu, 253–72. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2019. ↩

-

Mbembe, Achille. “Necropolitics.” Translated by Libby Meintjes. Public Culture 15, no. 1 (2003): 11–40. Mbembe, Achille. Necropolitics. Translated by Steven Corcoran. Duke University Press, 2019. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1131298. ↩

-

Casid, Jill H. “Doing Things with Being Undone.” Journal of Visual Culture 18, no. 1 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1177/1470412919825817. ↩

-

Islekel, Ege Selin. Nightmare Knowledges: Epistemologies of Disappearance.” 257. ↩

-

Washington, Harriet A. Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present. New York: Harlem Moon & Broadway Books, 2006. ↩

-

Lederer, Susan. Subjected to Science: Human Experimentation in America before the Second World War. ↩