Introduction

Specimen Studies

0.1.1 | 0.1.2 | 0.1.3 | 0.1.4 | 0.1.5Methods

0.2.1 | 0.2.2The Structure of this Dissertation

0.3.1Tuberculosis' Visual Culture

Visual Practices in Medical Culture

1.1.1 | 1.1.2 | 1.1.3Seeing and Settling in the Sanatorium Movement

1.2.1 | 1.2.2 | 1.2.3 | 1.2.4 | 1.2.5Teaching Public Health

1.3.1 | 1.3.2 | 1.3.3 | 1.3.4 | 1.3.5Representing Doctors in Tuberculous Contexts

1.4.1 | 1.4.2Using Human Specimens in the Study of Tuberculosis

Seeing Disease in Methyl Violet

2.1.1 | 2.1.2 | 2.1.3 | 2.1.4Case Histories

2.2.1 | 2.2.2 | 2.2.3 | 2.2.4Visceral Processes

2.3.1 | 2.3.2Relation

2.4.1 | 2.4.2 | 2.4.3Arts-Based Inquiry

Introduction

3.1.1 | 3.1.2 | 3.1.3 | 3.1.4Terminal Imaginaries & Tuberculous Imaginaries

3.2.1 | 3.2.2 | 3.2.3 | 3.2.4 | 3.2.5 | 3.2.6Dermographic Opacities

3.3.1 | 3.3.2 | 3.3.3 | 3.3.4Tactical Pretensions

3.4.1 | 3.4.2 | 3.4.3Designing Opacity

A Shift towards the Anticolonial

4.1.1 | 4.1.2 | 4.1.3 | 4.1.4Refusals and Opacities

4.2.1 | 4.2.2 | 4.2.3 | 4.2.4Digital and Ethical Workflows

4.3.1 | 4.3.2 | 4.3.3 | 4.3.4 | 4.3.5Conclusion

4.4.1Coda

Prometheus Undone

5.1.1 | 5.1.2 | 5.1.3 | 5.1.4Appendix

The Tuberculosis Corpus

X.1.1 | X.1.2 | X.1.3Web Design

X.2.1 | X.2.2 | X.2.3 | X.2.4Installation Materials

X.3.1 | X.3.2 | X.3.3Index

As the wet tissue specimen depends on a longer history than its isolation and display, I want to now turn to think more carefully about the actual transformations from a human patient’s body to its staging in fluid. Undergirding my argument is an assumption that wet tissue specimens are socially constructed representational objects, and that the phenomena they represent are entangled in cultural, technological, and ideological processes. This framing stresses that while there is a biological phenomenon which has occurred within the body of a patient, the means of framing, understanding, and relaying a phenomenon is distinctly human. Wet specimens are a perfect example of this kind of construction, insomuch as a successfully produced wet specimen is delicately, and artfully created.1 To make a wet specimen requires a great deal of work: draining blood, cutting away uninteresting bone or viscera, delicately framing the object through careful removal of tissues, placing pins and glass plates, and submerging the organ in a preserving fluid. It is an involved process circumcised at every point by a doctor’s hand (2.2.1).2 Where a case history produces a kind of value in what is revealed, so does the process of removing, framing, and articulating the organ make an epistemological aesthetic.

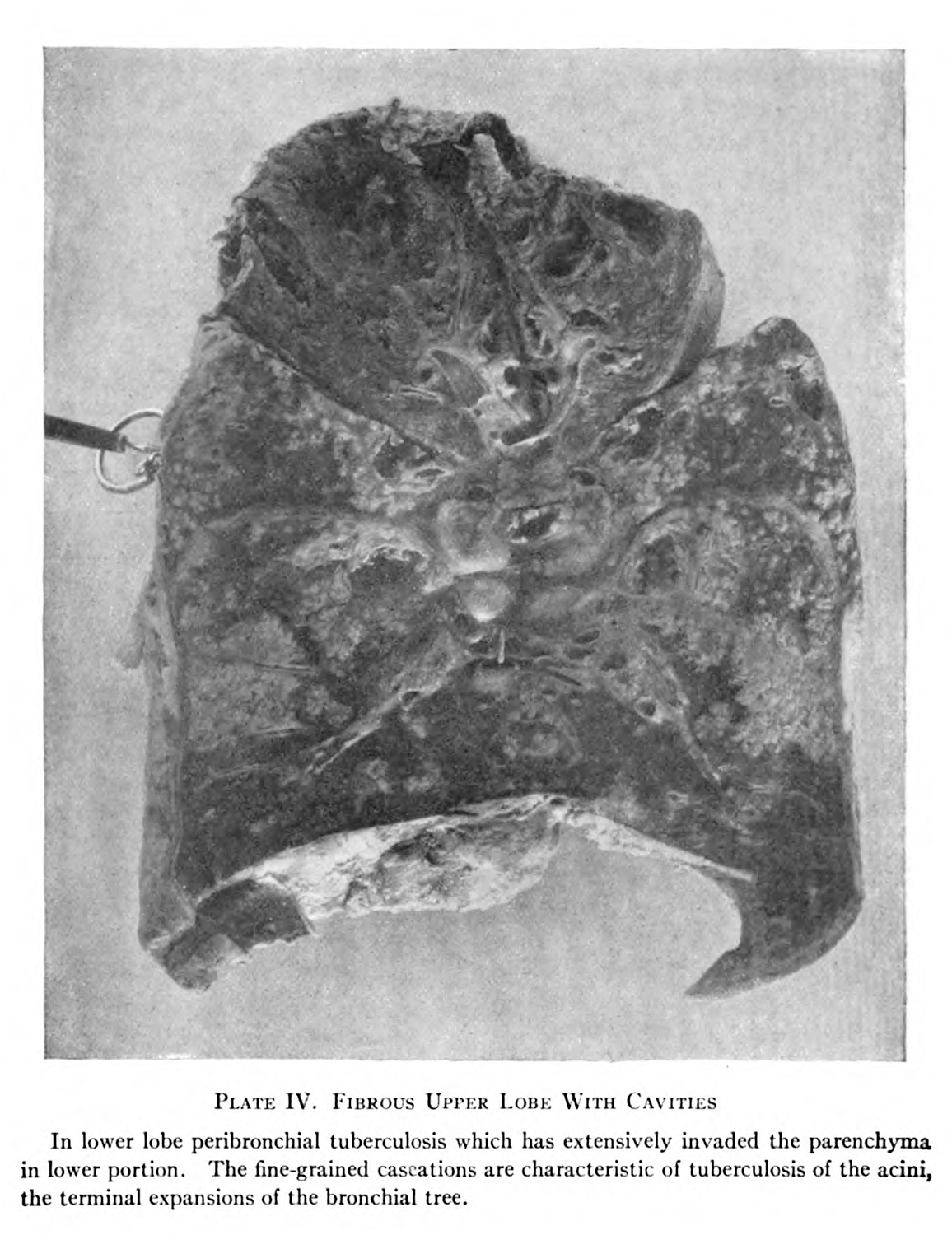

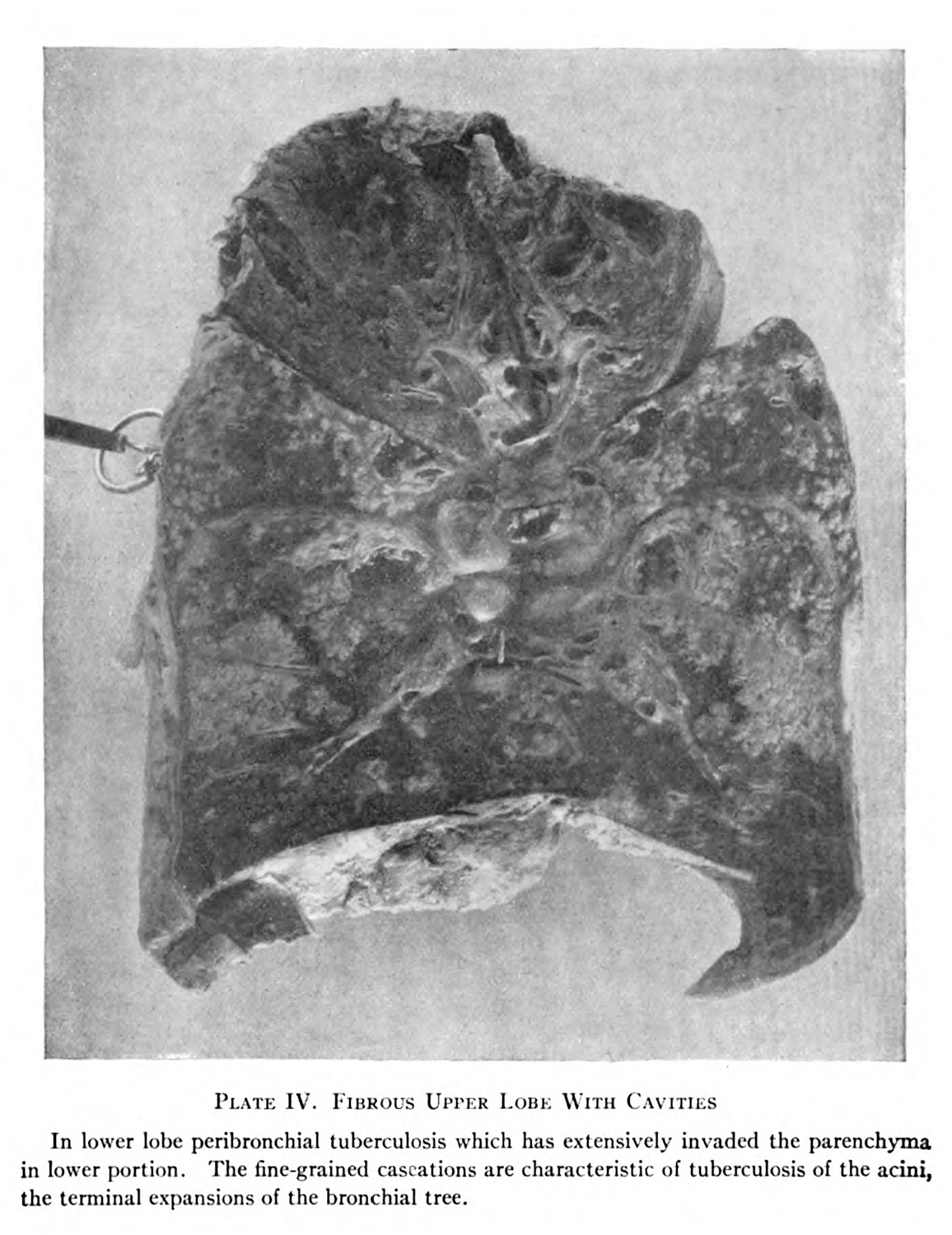

The production of a specimen, like a lung displayed in a 1919 American Review of Tuberculosis article, is marked by so much care and attention (fig. 1). I turn to this object to think about the processes of framing, and to consider how the specimen is produced in this manner. This section of a lung has been taken from the body of a patient at autopsy, and the marks of human intervention are clear: it has been cut so as to display a plane of vision. A viewer is assumed to be able to understand that this section is part of a greater whole (2.2.1), and following clinical visuality (2.2.2), understands that this section is different than what an anatomically normal lung might look like. The caption helps point to the lung’s pathologies, and so does the choice to cut at this point, to photograph at this angle, and to pin the left side. Every decision makes the intended object, the pathological difference in the lung, the focus.

Figure 1. A lung autopsied as part of research into tuberculosis. From Bushnell, George E. ”Manifest Pulmonary Tuberculosis,” The American Review of Tuberculosis 2. (1918-1919), 171.

This example comes from an essay written by George E. Bushnell, which was penned to assist in diagnosis of tuberculosis, with specific interest for military service. Bushnell had been a prominent doctor during World War I, developing a robust protocol for diagnosing tuberculosis in enlisted troops. Bushnell had spent more than a decade running the hospital at Fort Bayard, in New Mexico, before he was tapped by the surgeon general to open the Office of Tuberculosis in the Division of Internal Medicine in 1917. The U.S. army had experienced difficulty in reliably determining whether its soldiers were sick with the disease, with misdiagnosis being a prominent concern, as they tried to enlist as many able-bodied men as possible. Bushnell spoke against tuberculin as a diagnostic method, and blustered against how often patients would be diagnosed with tuberculosis without a positive sputum test (2.1.3).3

Bushnell’s goal for this essay was to better describe incipient tuberculosis:

The text books, with their numerous subdivisions and wealth of detail, are confusing to the beginner, who is apt to feel at a loss when confronted by the varied signs of large tuberculous lesions. Yet the importance of skill in the diagnosis of age and kind of lesions present in a given case is great for all who have to do with tuberculous cases, for upon such diagnosis depends the prognosis. Prognosis is the first and last thing demanded of the physician by the patient’s friends, and upon the prognosis which he gives he is judged.4

The wet specimens provided in the essay give context to the phenomena occurring within the patient’s body. This plate was used to describe the progression of the disease within a patient’s lung:

The tubercle invasion is checked in the bronchial tubes which run downward and outward and directly downward, but such checking tends to assemble the invaders, returning them to the hilus whence they can act as reinforcements else where. The bronchi which extend laterally through the lower lobe, since their lymph channels run nearly at right angles to the diaphragmatic suction, are particularly exposed. It is common to see an extension along such a bronchus which shows itself at autopsy as a series of bronchopneumonic foci grouped about the tube ( Plate IV ). Here we have what is really an atypical peribronchial extension. During life our means of diagnosis do not permit the recognition of the fact which is, however, worthy of note as respects the prognosis. We may put the facts in this way. Extensions in the lower lobe are more apt to involve the entire course of the bronchus, from the hilus to the periphery, than extensions higher up in the lung. What we judge of as superficial extensions of perhaps slight extent are here really the outward manifestations of a very considerable process, the greater part of which runs its course in the deep lung.5

The description Bushnell provides gives both explanation as to why the phenomenon occurred, and its association with the assumed pathological development. A military man, Bushnell articulates the site of the body as an invasion, which was a common theme in the discourses around the disease in the period,6 and his description of the organ and its pathologies narrates the disease’s aftermath. The specimen provides a visual example of the progression Bushnell describes, and it is framed, edited, and prepped for his audience.

In the preparation of the specimen, there are two kinds of framing at play: the first form of framing is a reduction in unnecessary material. While obvious, it is important to remember the labor and care that is made to take this organ out of its original context: we are not gazing into the patient’s chest cavity. All of the material that has been stripped away has been deemed unimportant for the sake of the pathological argument. The material is disciplined in such a manner so as to remove any unnecessary noise in the form of unwanted viscera, a kind of scientific and medical reductionism (2.1.3).7

The second kind of framing is a contextual one: while the pathological phenomenon is the target of attention, in isolation it has no meaning.8 The object in context, whatever context the creator of the specimen deems valuable, is necessary for it to function: this context points to the phenomenon’s location in the lung, and it is in this context that a medical viewer can understand how that phenomenon might have affected the organ. It helps show the relationship of this phenomenon for future diagnostic or symptomatic conceptions of the disease.

I use the term ‘discipline’ to refer to Michel Foucault’s later-career approach to knowledge work: that power—the knowledge-defined processes which produce meaning and its contexts through collective conversation—functions in such a way as to define certain phenomena in ways that contain that phenomena within a predetermined set of metrics. The prisoner, for Foucault, is doubly disciplined both in the structures which confine them within the prison, but also within the knowledge/power systems which determine them as deviant (2.2.3).9

The specimen works similarly: it produces the contexts and discourses within which the specimen is valuable, and produces the aspects of the specimen which are most important. These processes are implicitly political: most obviously in the case of the modern prison system, and more subtly for the understanding of tuberculosis. The reduction of the body into a specimen, the boring of vision down to the cell, assumes that with infinite specificity there will be a potential for control (0.1.4). Control is, of course, valuable insomuch as perfect knowledge may afford the development of pinpointed, hypertechnical, miraculous cures, but it also is an explicitly totalitarian logic.10

Like with the three-body problem—an astrophysical thought experiment which shows how it is impossible to produce a simple model to describe and predict the gravitational effect of three different celestial bodies upon one another—understanding a single phenomenon in isolation is at odds with the realities of deeply complex and interrelated natural world. Keeping the locus of knowledge at small, specific scales addresses complexity, while also affording the continuation of philosophical presumptions regarding the individual (2.2.3). If the individual is a single entity, where the disease is neatly contained, and the organ—itself an object whose boundaries are set and defined—is the seat of the disease then it is easy to reduce down, to point blame to individuals (1.3.4; 1.3.5), and to place value in the discrete embodied space of the cadaver. The leaky,11 embedded, and entangled12 self muddies the essential origins and results of a given disease.

Returning to the specimen imaged at the beginning of this section (fig. 1), it has been neatly disciplined to foreground these specific understandings of the disease. This lung depicts the progression of tuberculosis in its upper lobe. It represents these assumptions, in such a manner as designed by George E. Bushnel. The U.S. Army doctor viewed the disease as incipient, and thought almost all of the men he surveyed had been infected with the disease at a young age.13 His views were interlinked with racial conceptions of health: he penned a book on tropical medicine, A study in the epidemiology of tuberculosis, with especial reference to tuberculosis of the tropics and of the negro race in 1920, a few years before his death in 1924,14 which viewed the prevalence of the disease as a means of protection, tying the mass deaths of newly contacted Indigenous communities to the spread of tuberculosis (1.3.5).15

I chose this wet specimen prepared and reproduced by Bushnell because of the doctor’s tenure in the U. S. Army. The production of this representation is circumcised by the doctor’s actions (2.2.1),16 but it is also tied to the history of the patient who died (2.2.3), who has otherwise been erased in this argument. Bushnell’s centrality in the diagnosis and treatment of military men heading to the trenches asks a further question: where did he procure this lung? Most likely, it was taken at autopsy of a man who died under Bushnell’s care at the hospital at Fort Bayard or during his time in Washington, D.C.. Had this man consented to this autopsy? Was his inclusion in the military enough to give the legal and moral authority to circumvent his consent? Did he die far from home? Had he made his way across the Atlantic and returned, or was he stopped early in his enlistment? What was his treatment, and who attended to him? What other portions of his body were disassembled?

-

And the production of high quality specimens has been a mark of success for some medical scientists, like John Hunter in the eighteenth century.

For discussion of the use of famous collections, see: Alberti, Samuel J. M. M. Morbid Curiosities: Medical Museums in Nineteenth-Century Britain. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011.

For an example of how aesthetics and skill are interlinked in medical knowledge production, see: Hakosalo, Heini. “The Brain under the Knife: Serial Sectioning and the Development of Late Nineteenth-Century Neuroanatomy.” Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences 37 (2006): 172–202. ↩

-

Derrida, Jacques. Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression. Translated by Eric Prenowitz. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996. ↩

-

Interesting to note here: the U.S. Army did make use of x-rays for their diagnosis, but Bushnell saw it as one of many diagnostic methods that could pinpoint the disease, but not something that was itself incontrovertable.

Byerly, Carol R. “Tuberculosis in World War I.” In Good Tuberculosis Men: The Army Medical Department’s Struggle with Tuberculosis, 105–53. Houston, Texas: Office of the Surgeon General, 2013. ↩

-

Bushnell, “Manifest Pulmonary Tuberculosis,” The American Review of Tuberculosis 2. (1918-1919), 140. ↩

-

Ibid., 153-54. ↩

-

Many scholars have linked the invasive and war-based narrative surrounding disease, medical technological development, and funding pleas.

For a good example of how a military metaphor drove cancer developments, see: Mukherjee, Siddhartha. The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of Cancer. New York: Scribner, 2010.

For an essay that collects some theoretical critiques of military metaphors in medicine, see: Goffey, Andrew. “Homo Immunologicus: On the Limits of Critique.” Medical Humanities 41 (2015): 8–13. ↩

-

I use reductionism here, but the scholarship on this concept that I have found has not been great. More work should be done in applying science and technology studies (STS) approaches to this topic.

Miles, Andrew. “On Medicine of the Whole Person: Away from Scientific Reductionism and Towards the Embrace of the Complex in Clinical Practice.” Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice 15 (2009): 941–49. ↩

-

This is one of the reasons why dermatology has so many full body subjects. Purcell, Sean. “Dermographic Opacities.” Epoiesen, 2022. http://dx.doi.org/10.22215/epoiesen/2022.1. ↩

-

Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. New York: Vintage Books, 1995.

Michael Curtis also writes about discipling knowledge apparatuses.

Curtis, Scott. The Shape of Spectatorship: Art, Science, and Early Cinema in Germany. New York: Columbia University Press, 2015. 37-44. ↩

-

Glissant, Édouard. Poetics of Relation. Translated by Betsy Wing. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1997. ↩

-

Leaky body feminism has critiqued notions of any human body being a single, concrete subject.

Jue, Melody. Wild Blue Media: Thinking Through Seawater. Durham & London: Duke University Press, 2020 Irigaray, Luce. The Sex Which Is Not One. Translated by Catherine Porter and Carolyn Burke. Ithica: Cornell University press, 1985; Tuana, Nancy. “Viscous Porosity: Witnessing Hurricane Katrina.” In Material Feminisms, edited by Stacy Alaimo and Susan Heckman, 188–213. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2008. ↩

-

Fitzgerald, Des, and Felicity Callard. “Entangling the Medical Humanities.” In The Edinbgurgh Companion to the Critical Medical Humanities, edited by Anne Whitehead and Angela Woods, 35–49. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2016. ↩

-

Byerly, Carol R. “Tuberculosis in World War I.” In Good Tuberculosis Men: The Army Medical Department’s Struggle with Tuberculosis, 105–53. Houston, Texas: Office of the Surgeon General, 2013. ↩

-

Phalen, James M. “George Ensign Bushnell, Colonel, Medical Corps, U. S. Army.” The Army Medical Bulletin, no. 50 (1939). ↩

-

Bushnell, George E. A Study in the Epidemiology of Tuberculosis, with Especial Reference to Tuberculosis of the Tropics and of the Negro Race. New York: William Wood and Company, 1920. ↩

-

Derrida, Jacques. Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression. ↩