Introduction

Specimen Studies

0.1.1 | 0.1.2 | 0.1.3 | 0.1.4 | 0.1.5Methods

0.2.1 | 0.2.2The Structure of this Dissertation

0.3.1Tuberculosis' Visual Culture

Visual Practices in Medical Culture

1.1.1 | 1.1.2 | 1.1.3Seeing and Settling in the Sanatorium Movement

1.2.1 | 1.2.2 | 1.2.3 | 1.2.4 | 1.2.5Teaching Public Health

1.3.1 | 1.3.2 | 1.3.3 | 1.3.4 | 1.3.5Representing Doctors in Tuberculous Contexts

1.4.1 | 1.4.2Using Human Specimens in the Study of Tuberculosis

Seeing Disease in Methyl Violet

2.1.1 | 2.1.2 | 2.1.3 | 2.1.4Case Histories

2.2.1 | 2.2.2 | 2.2.3 | 2.2.4Visceral Processes

2.3.1 | 2.3.2Relation

2.4.1 | 2.4.2 | 2.4.3Arts-Based Inquiry

Introduction

3.1.1 | 3.1.2 | 3.1.3 | 3.1.4Terminal Imaginaries & Tuberculous Imaginaries

3.2.1 | 3.2.2 | 3.2.3 | 3.2.4 | 3.2.5 | 3.2.6Dermographic Opacities

3.3.1 | 3.3.2 | 3.3.3 | 3.3.4Tactical Pretensions

3.4.1 | 3.4.2 | 3.4.3Designing Opacity

A Shift towards the Anticolonial

4.1.1 | 4.1.2 | 4.1.3 | 4.1.4Refusals and Opacities

4.2.1 | 4.2.2 | 4.2.3 | 4.2.4Digital and Ethical Workflows

4.3.1 | 4.3.2 | 4.3.3 | 4.3.4 | 4.3.5Conclusion

4.4.1Coda

Prometheus Undone

5.1.1 | 5.1.2 | 5.1.3 | 5.1.4Appendix

The Tuberculosis Corpus

X.1.1 | X.1.2 | X.1.3Web Design

X.2.1 | X.2.2 | X.2.3 | X.2.4Installation Materials

X.3.1 | X.3.2 | X.3.3Index

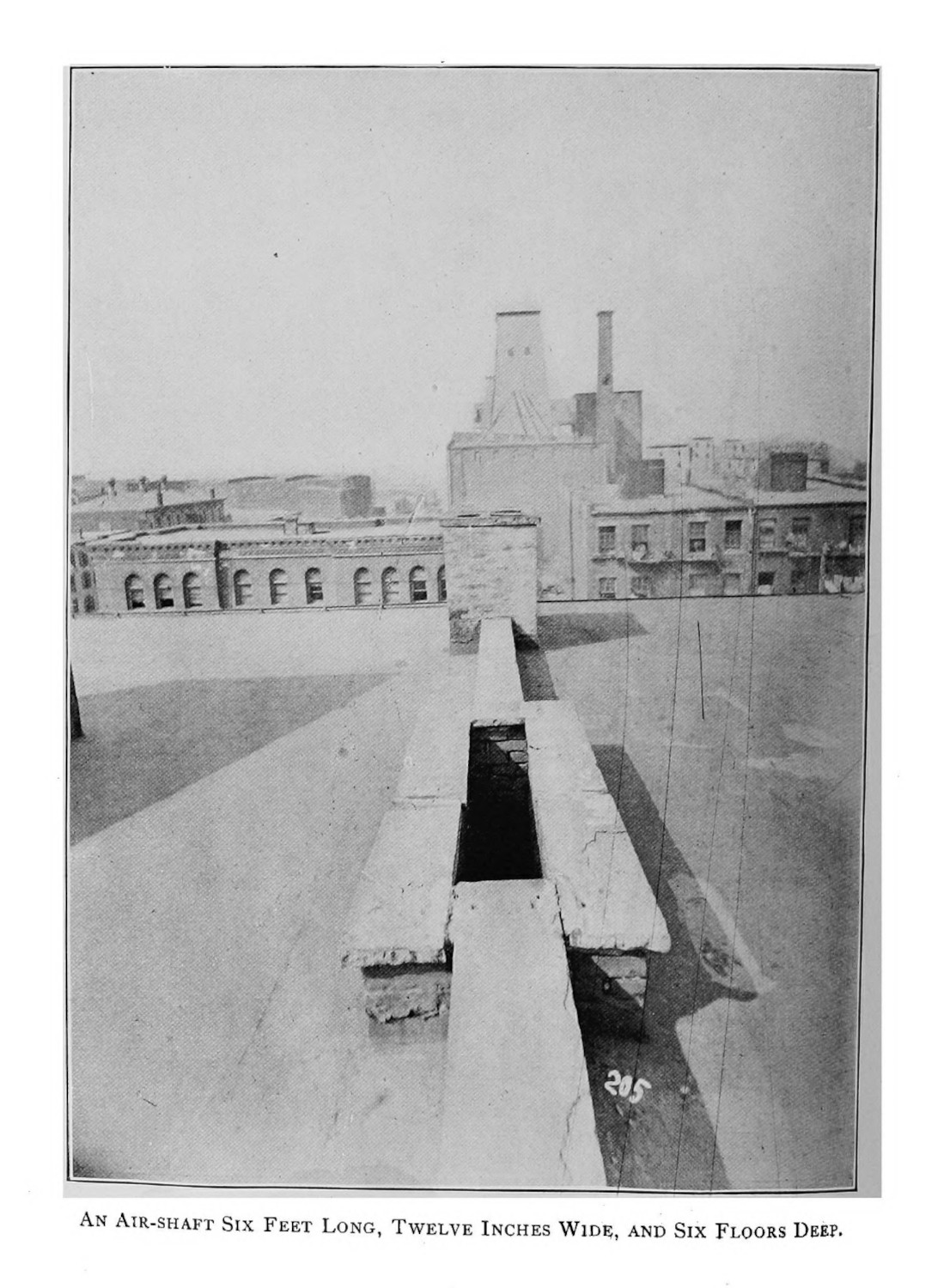

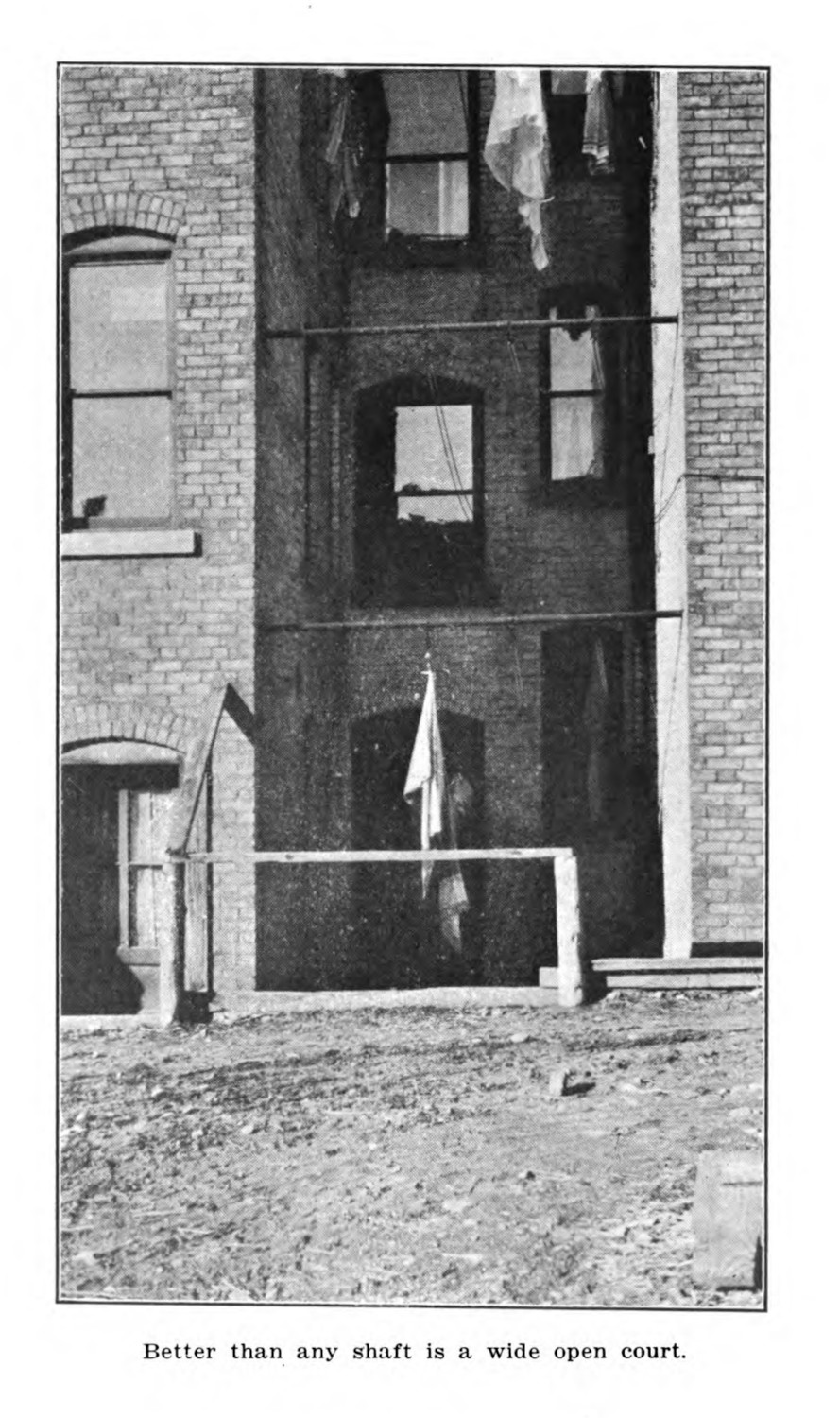

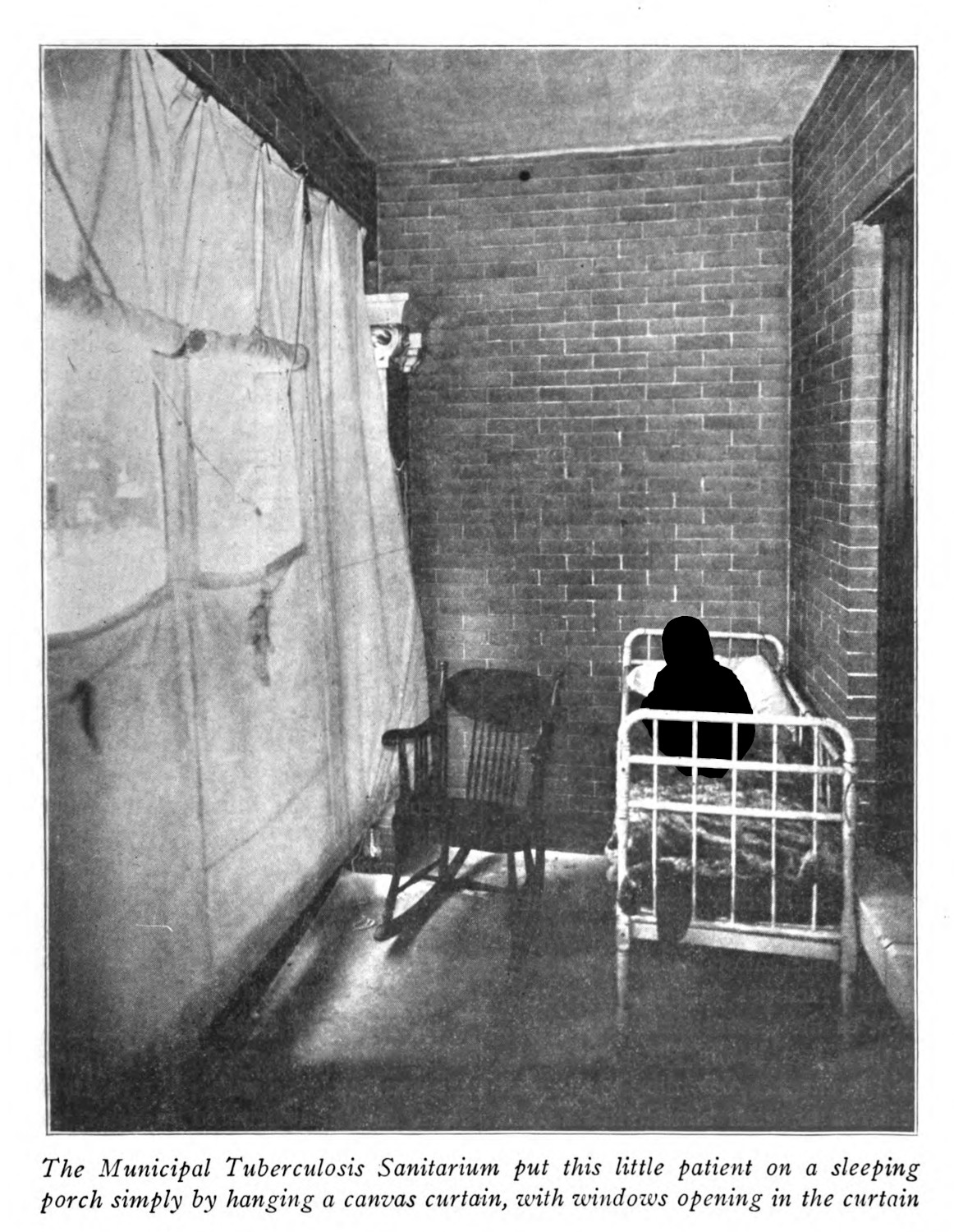

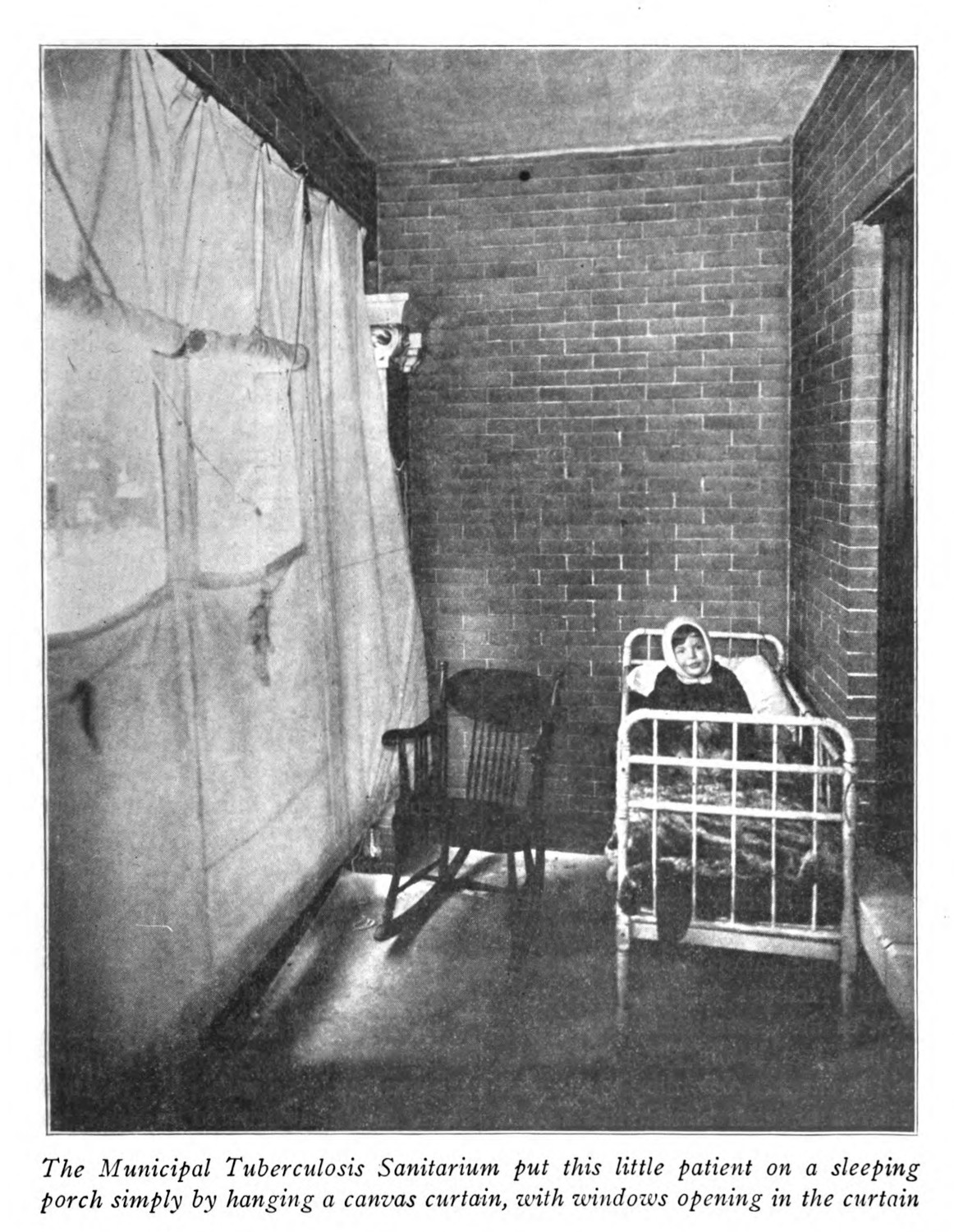

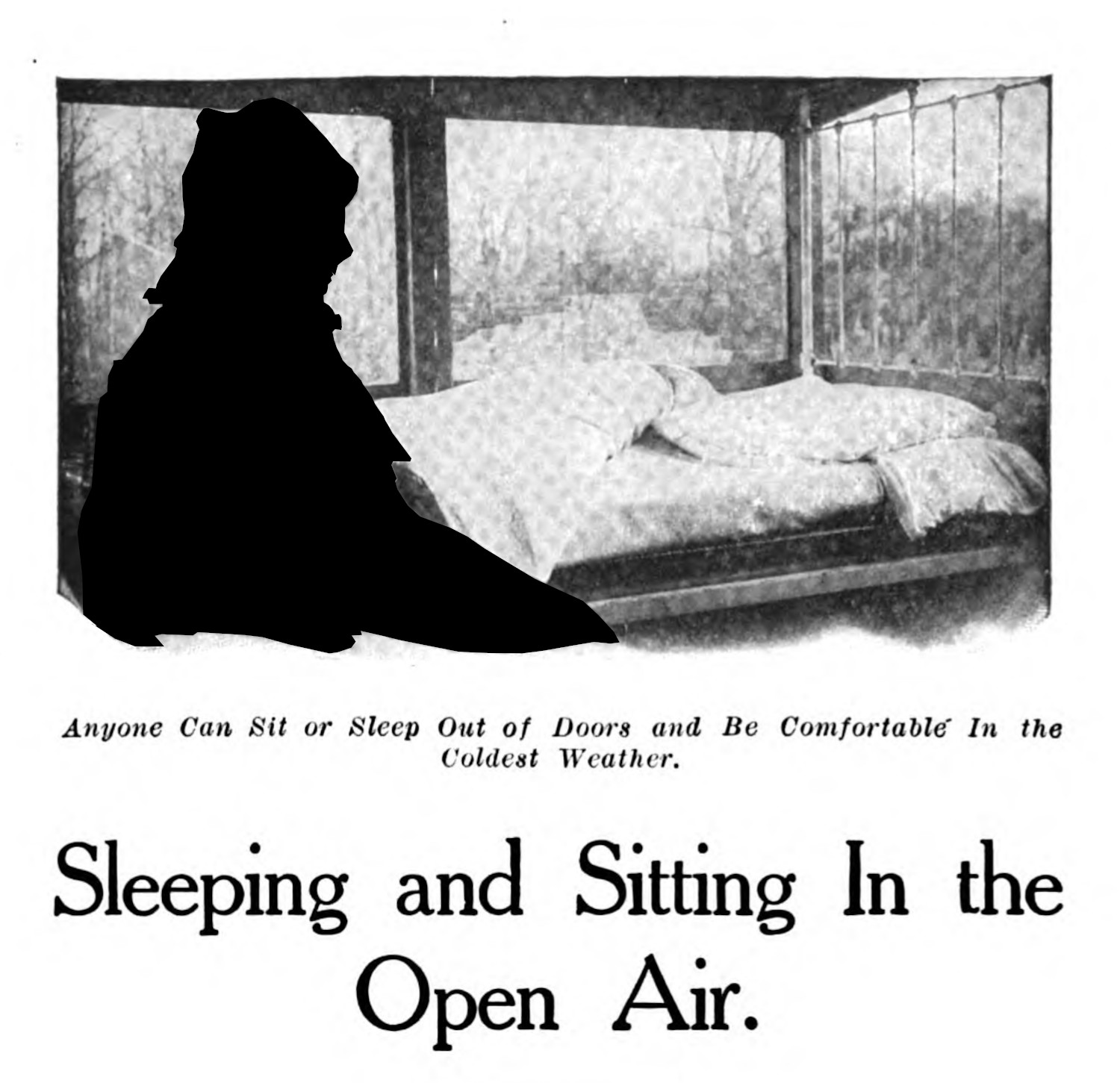

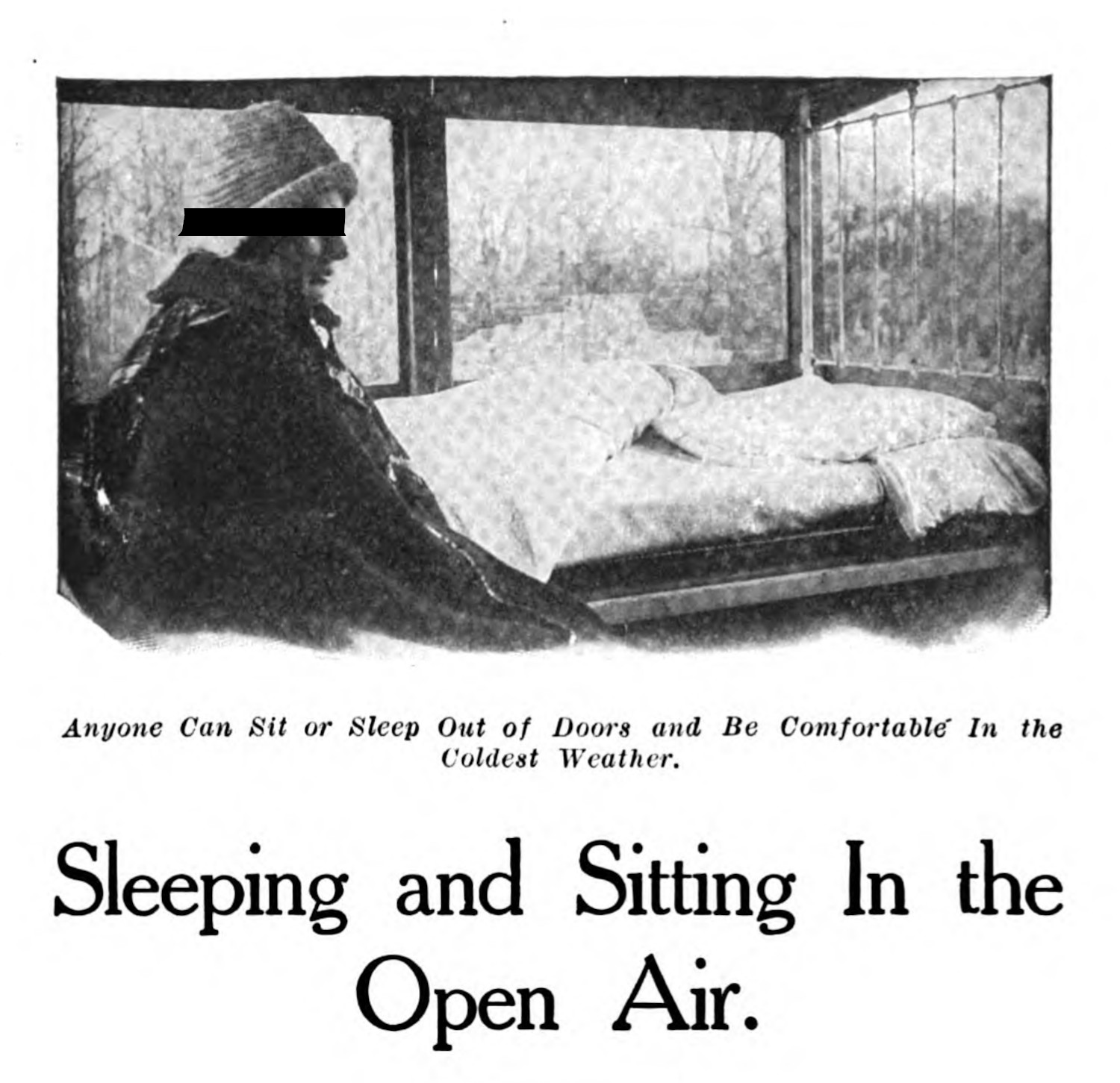

“The Morgue”, described in the previous section (1.3.2), represented a view which saw the environments in which patients with tuberculosis lived as being directly connected to their health. In these hygienic images which omit human subjects, there are a few running themes. The first is the most obvious: the clutter, the mess, the squalid conditions. These speak to a kind of hygienic approach to tuberculosis that focused on cleanliness. Associated with these examinations of the dirty, is also an interest in the less visible aspects of a living environment: airflow and access to sunlight (figs. 1 & 2). Public health publications were pushing for spaces that had more access to fresh air (fig. 3).

Airflow was a central tenet for climatic approaches to tuberculosis long before the disease was tied to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Health resorts were thought to be of benefit for patients with the disease, because the climates in which they were founded—dry or cold, mountainous or near the sea—would combat the disease’s progression (1.2.1; 1.2.2). However, at the turn of the twentieth century, these assumptions were shifting because doctors were noticing that the air in very different locations—like Colorado Springs, the Adirondacks, California, and North Carolina—was quite different, but the sanatoria in those locations seemed to be helping patients nonetheless. A simpler explanation was emerging: an escape from the city meant better health outcomes overall (1.2.2). As James Alex Lindsay argues in an 1887 monograph on the climatic treatment, “There is, in fact, no ideal climate for consumption; no happy Hygeia to which the consumptive can repair and draw in healing influences with every breath.”1 For Lindsay, the climatic treatment functions on a binary view of localities: he imagines the places where patients with tuberculosis live as crowded, dank, unhealthy places. Patients undergoing climatic treatment move from “comparatively sunless and depressing climates”, from “crowded populations and vitiated air”, from “the injurious influence of damp soil and of imperfect sanitation”, to give “the patient the great boon of change—change of air, change of diet, change of scenery, change of daily routine, change involving the abandonment of many an injurious habit which has long been the secret minister of disease.”2 Twenty years later, a summary of climatic approaches to care prepared by F. C. Smith for the United States Surgeon-General argued the same, writing: “in a man of fairly good personal and family history, the chances are that he may fight a winning battle if he lives out of doors in any climate, whether high, dry, and cold or low, moist and warm”.3

The popular imagination, built on the older practice of the health spa, was maintained even while climate was becoming less prominent in the literature. The concept of healing air, associated as it was with a regional disposition to help or hinder health, was narrowed and understood in the inverse. For certain public health threats, like tuberculosis, there were human manufactured causes that made populations more susceptible to the disease, and these causes could be addressed at a human scale, and which effected the public. Important, for this case study, is the remedy was placed on the responsibility of the patient: to seek help, to learn more hygienic modes of living, to move from poorly ventilated living situations.4

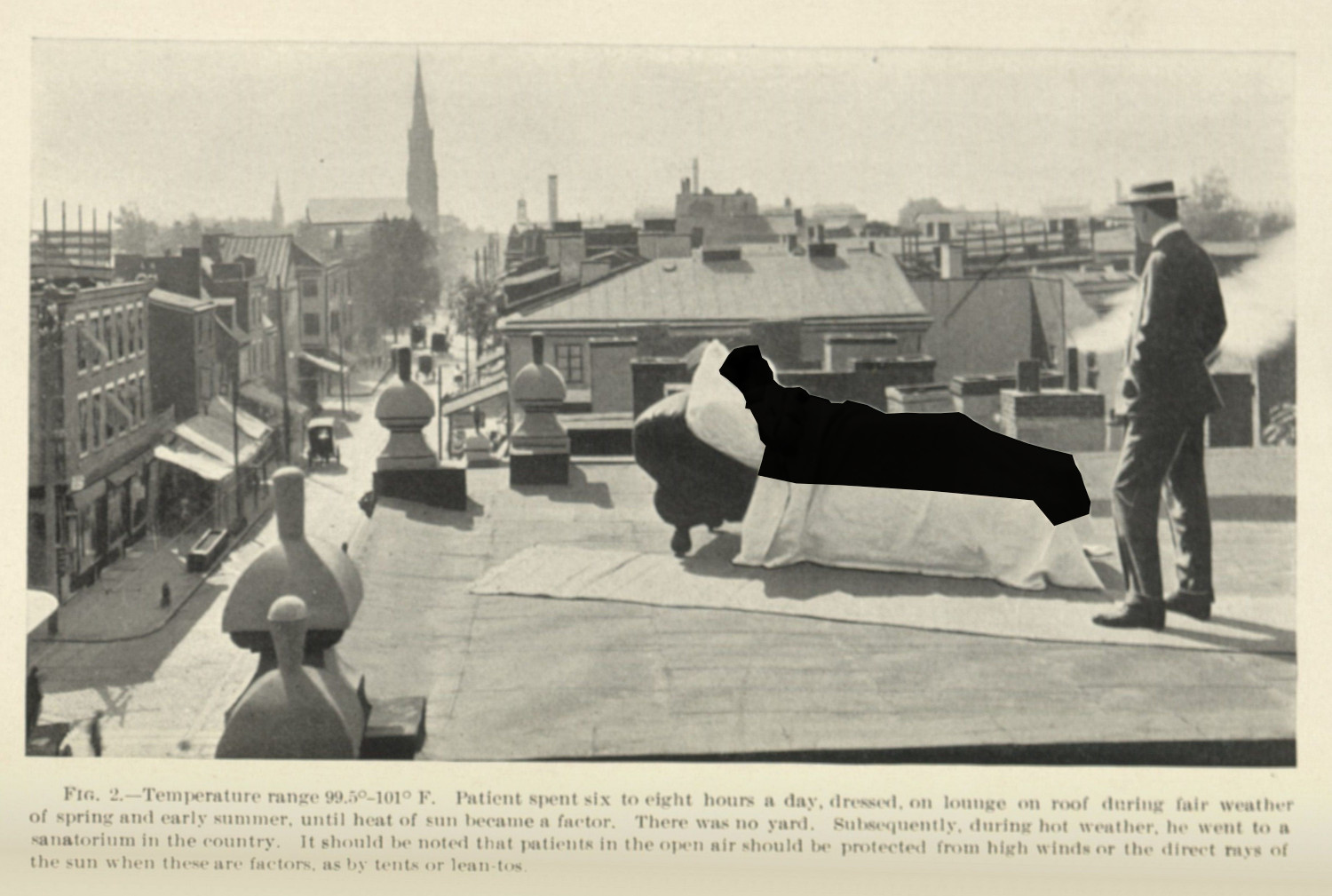

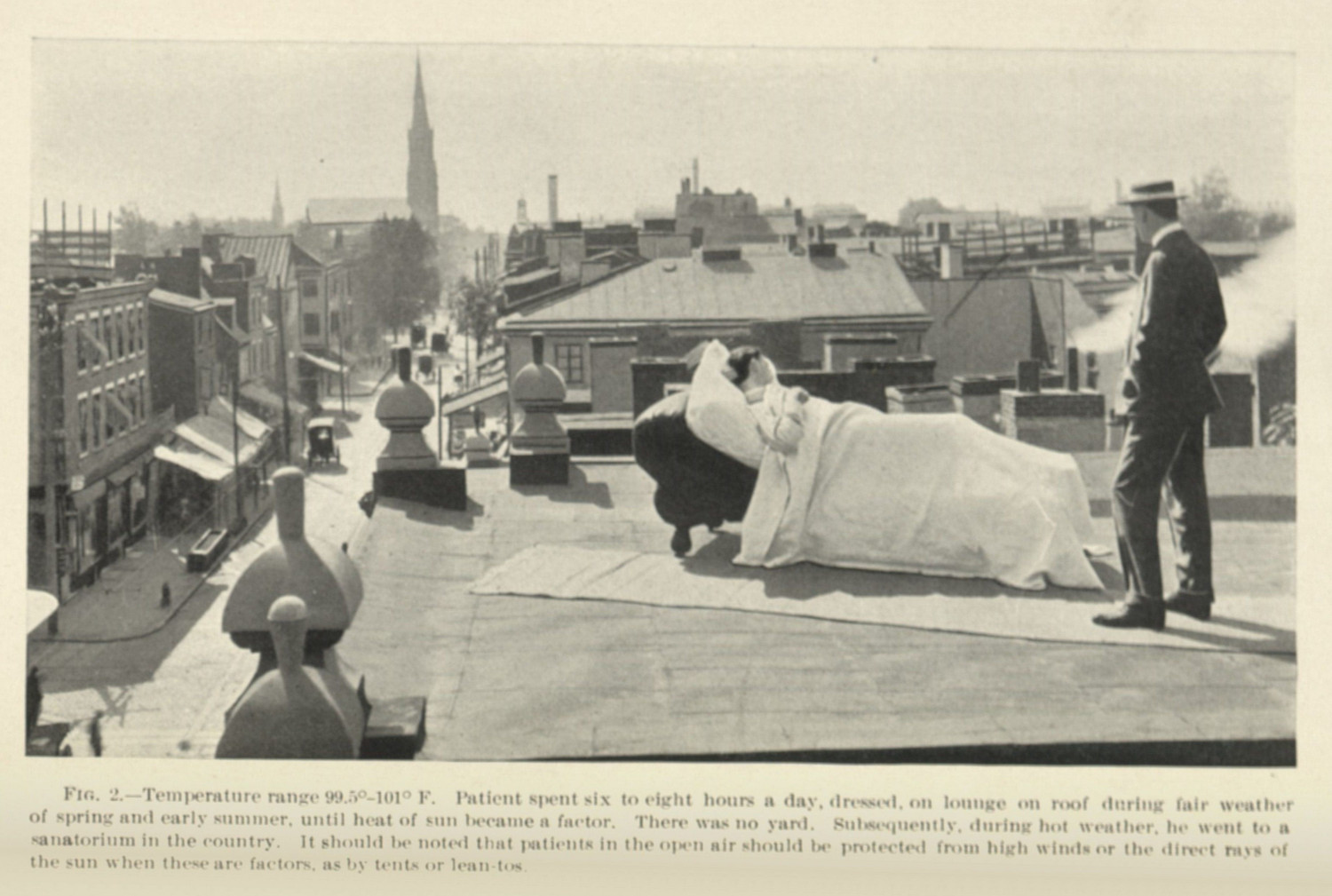

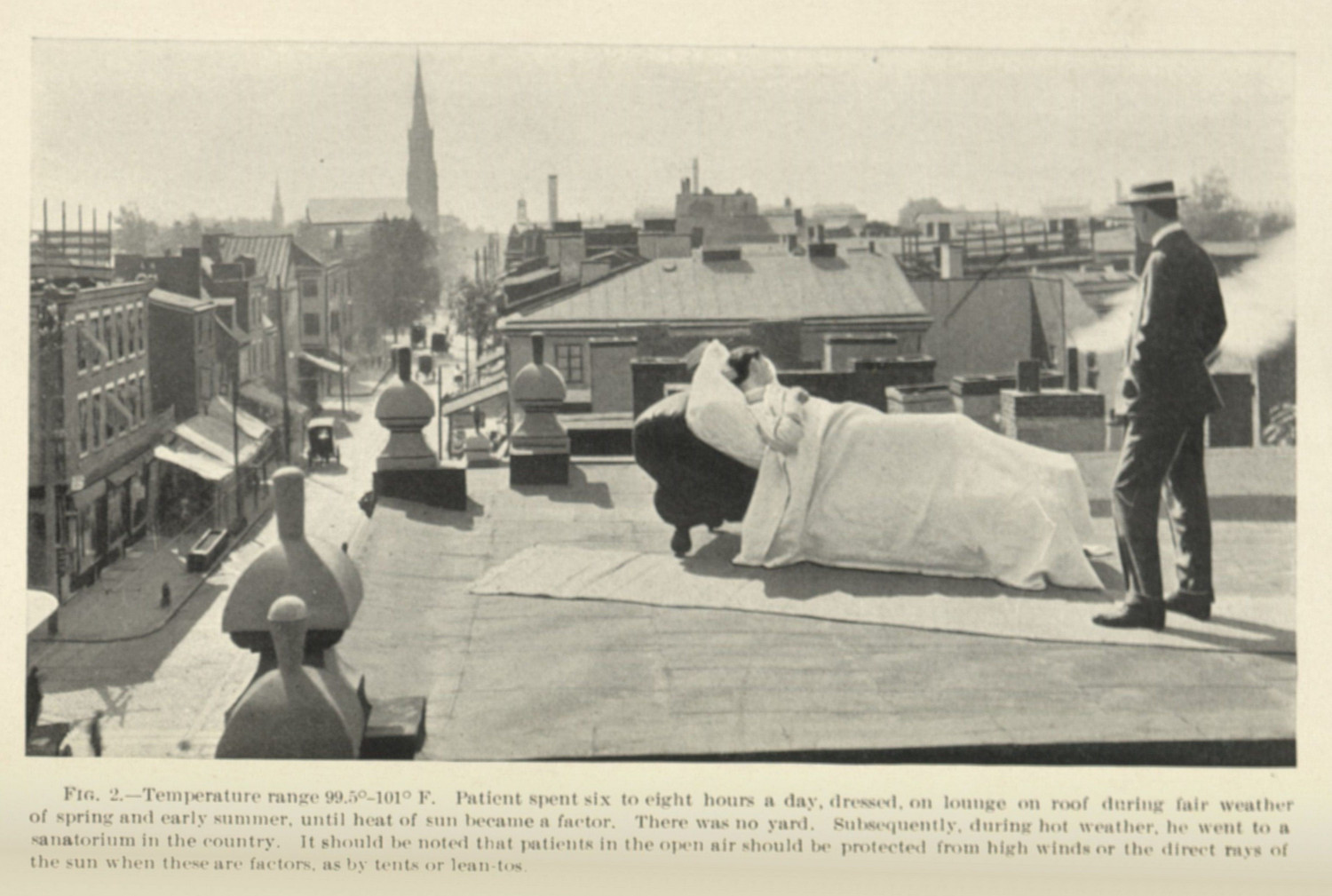

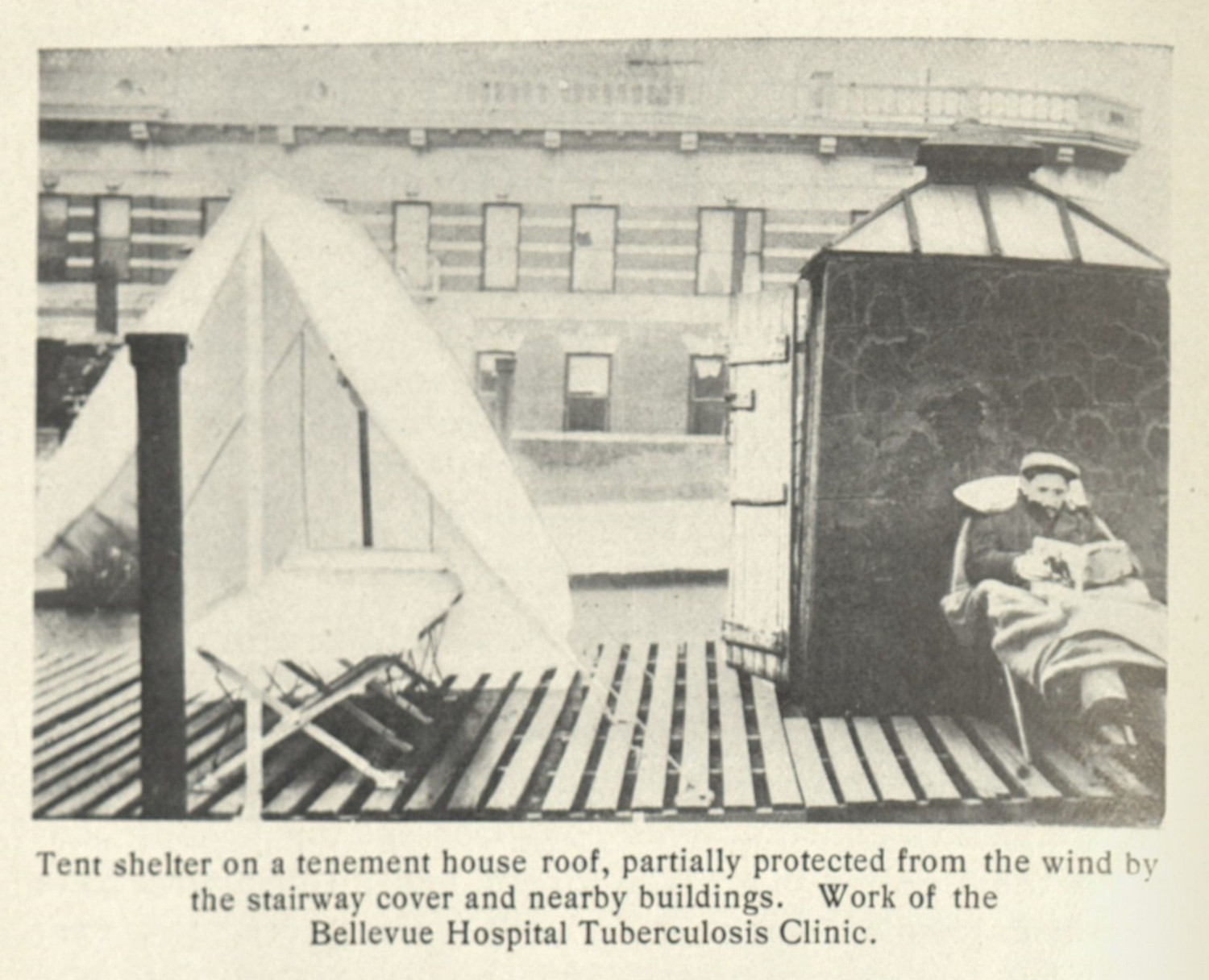

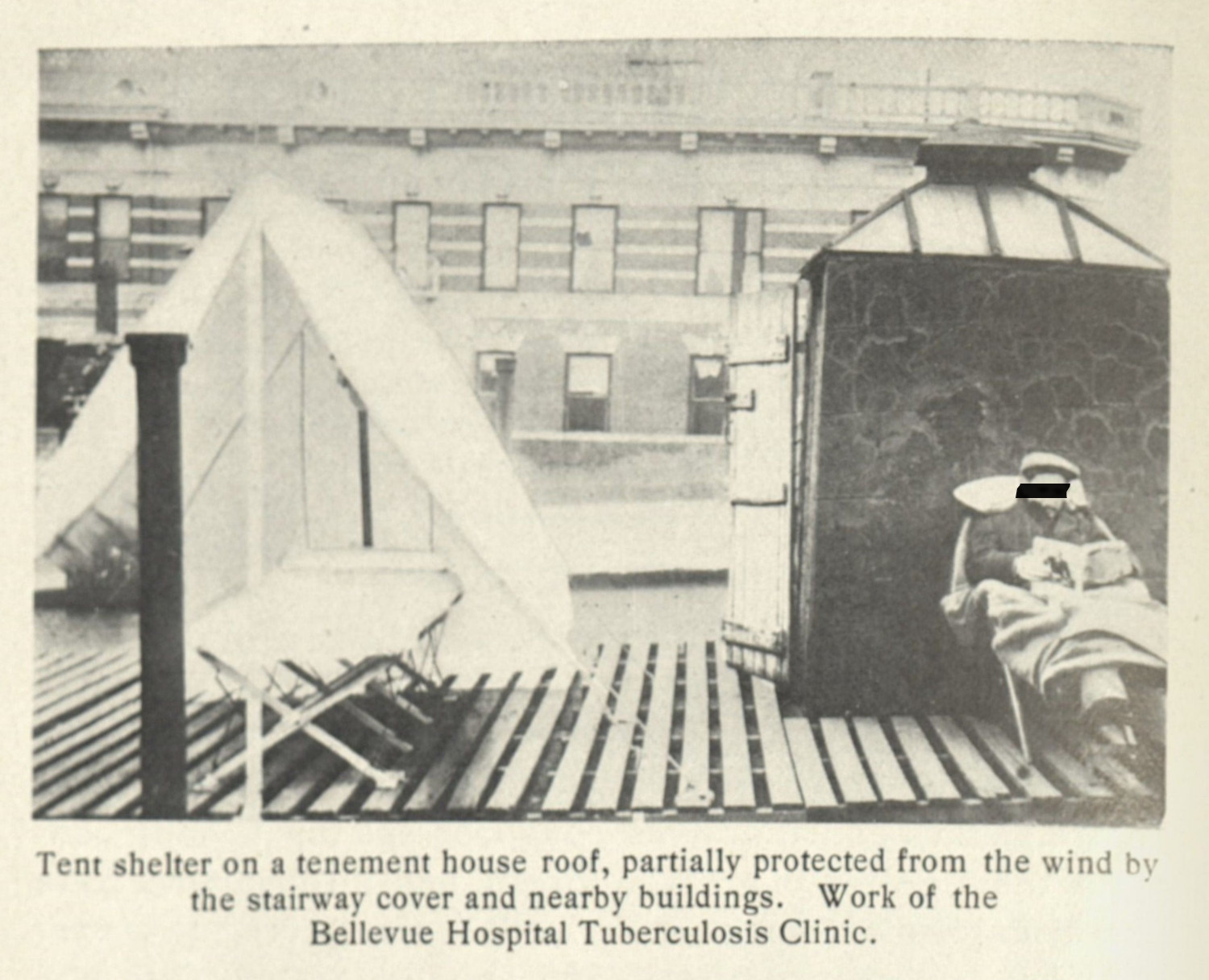

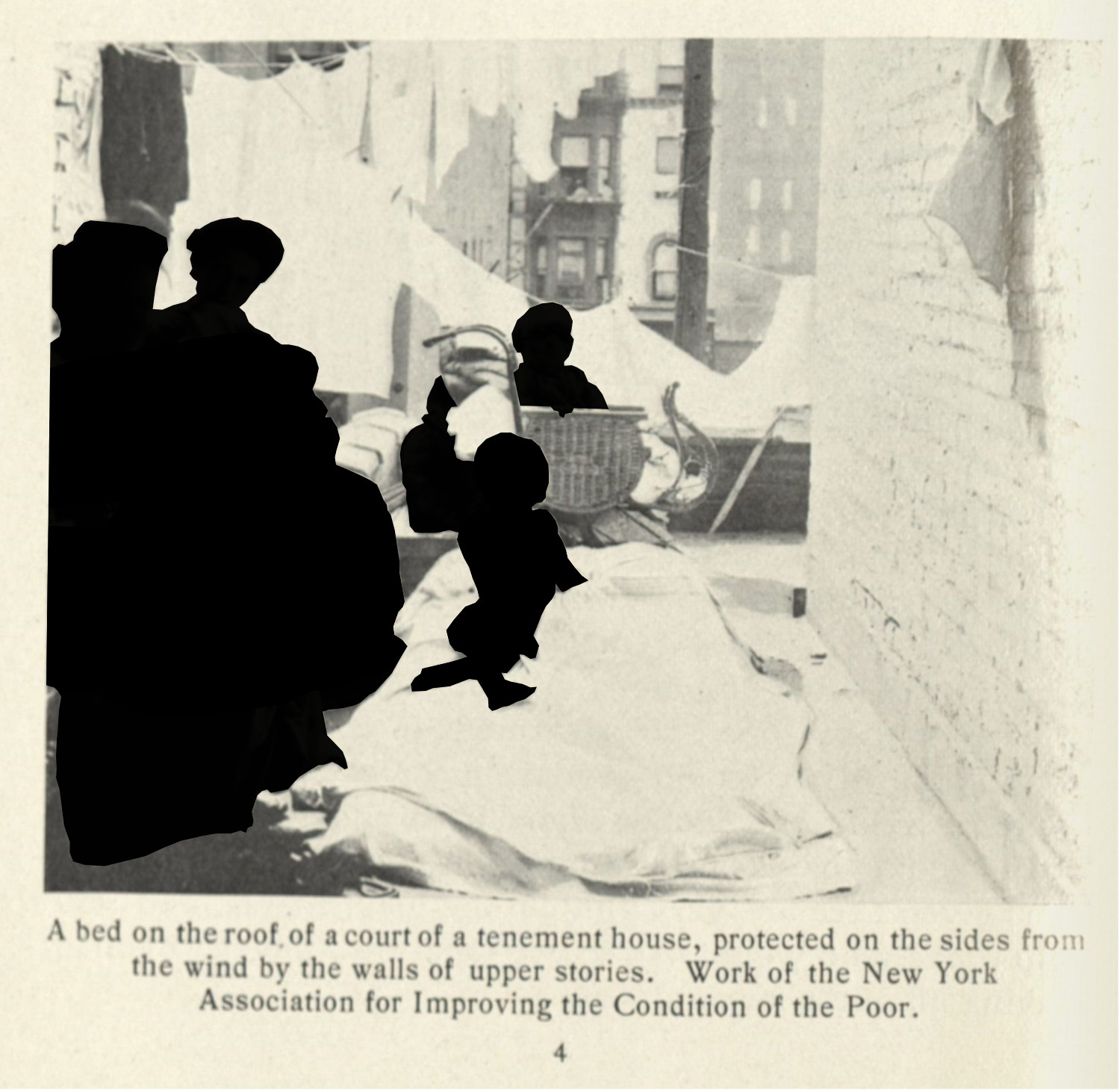

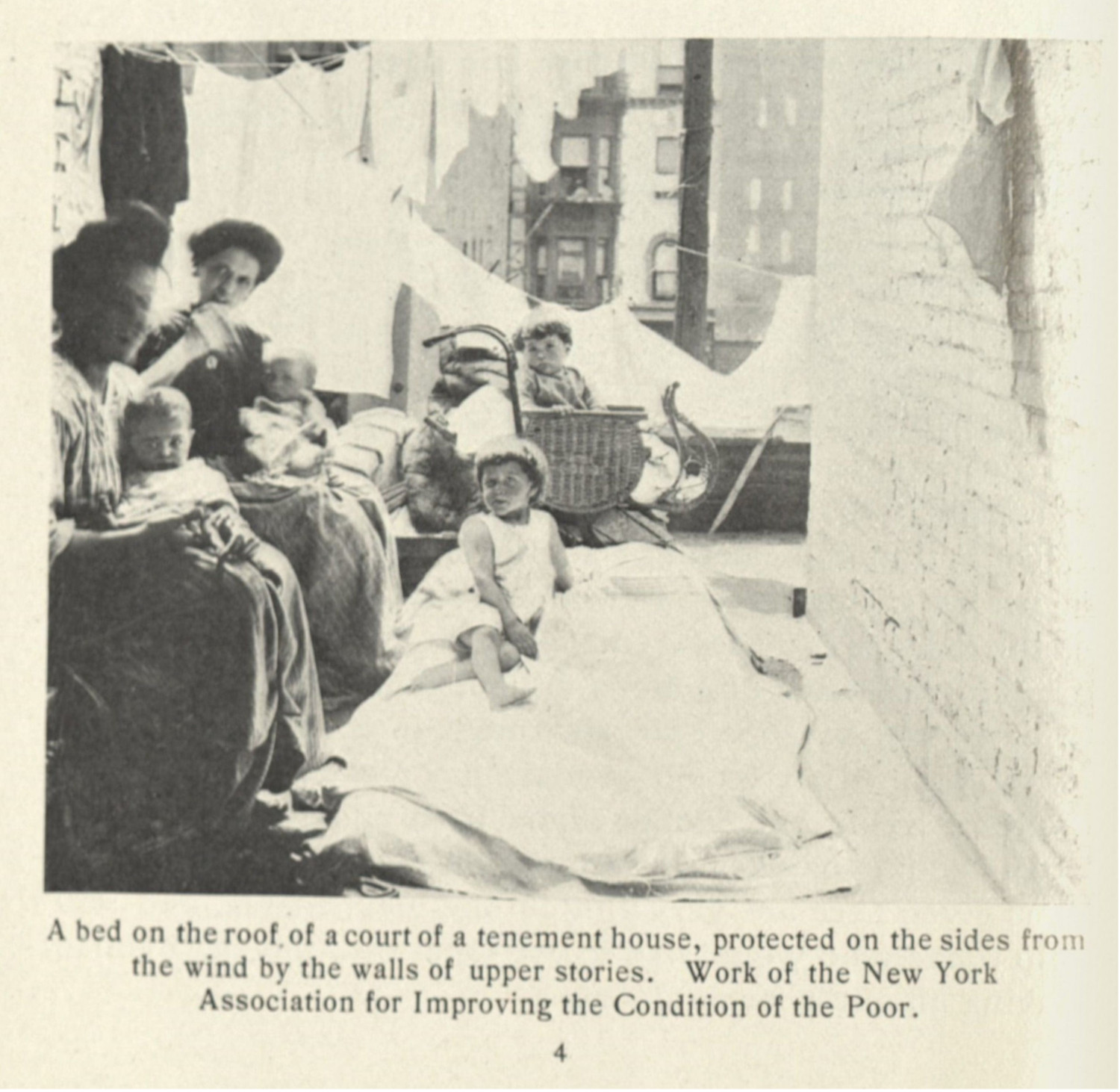

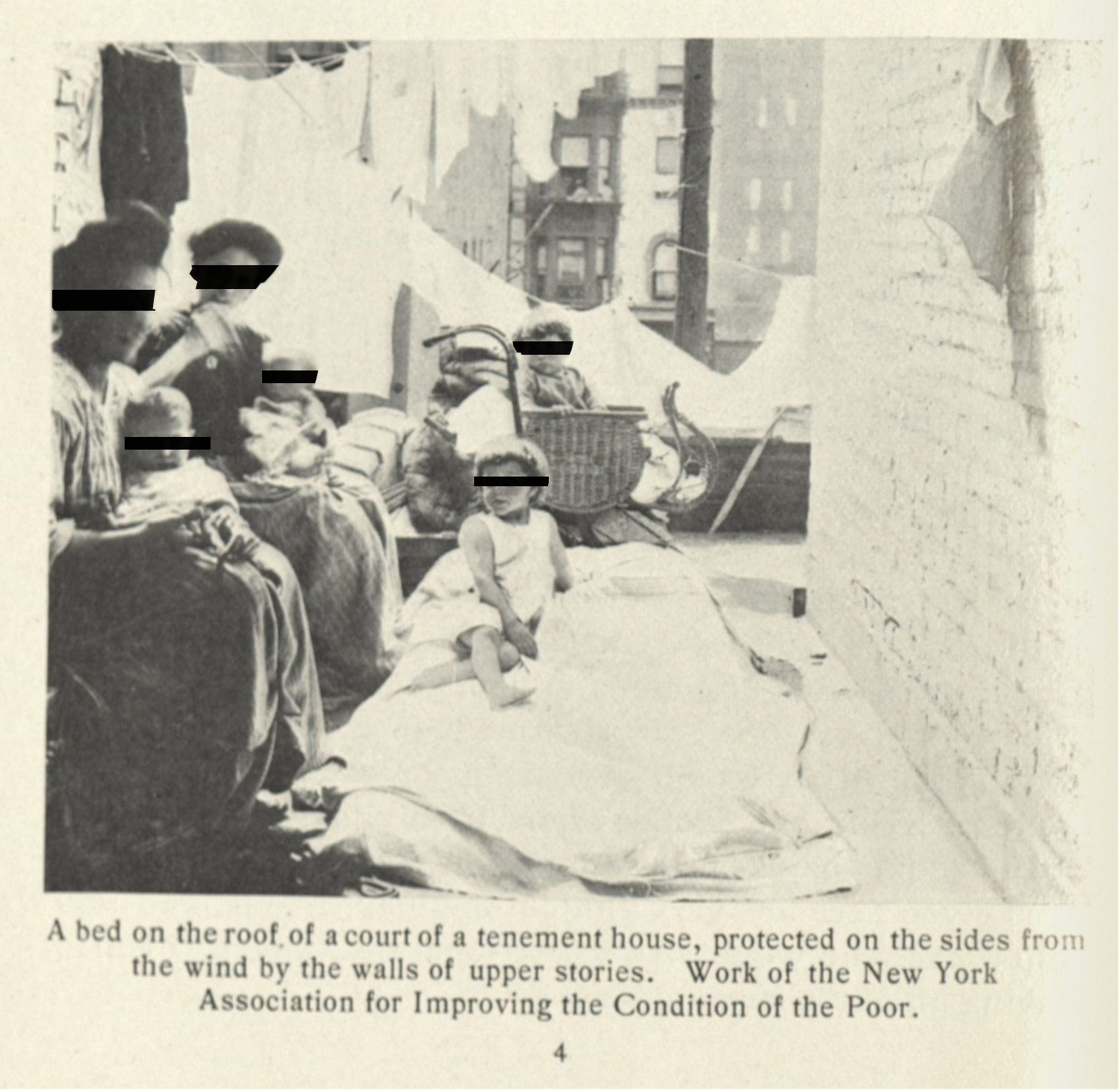

In this context then, the emphasis on airflow and light highlights the poor environments for lower class people living in urban centers. It was thought by medical professionals and public health workers that these people could recover, should they be treated with the rest cure and should they have access to open air, even if that air was still within an urban space. There are many images of adhoc and improvised rest cure spaces, with patients sleeping on rooftops (figs. 4 & 5), on fire escapes (fig. 6), and with their windows left open at all times (fig. 7 & 8).

Just as with the sanatorium, the solutions to tuberculosis were built (1.2.2; 1.2.4; 1.2.4). There were calls for a more architectural solution, which were levied against every dangerous building with poor light and ventilation. Unlike the previous case study, there was another approach layered on top of the construction of hygienic spaces (1.2.4): the poor were seen as being at least partially to blame for their illness. There were implicit assumptions that patients with tuberculosis could aways do more. An attention to cleanliness in living space, the intervention with the help of public funds, and the education provided by a public health nurse were all seen as solutions, but depended on the patients themselves ot listen to these actors in order to improve their health and the health of those around them (1.3.2; 1.3.4).

-

Lindsay, James Alex. The Climatic Treatment of Consumption: A Contribution to Medical Climatology. London: MacMillan and Co., 1887, 20. ↩

-

Lindsay, James Alex. The Climatic Treatment of Consumption: A Contribution to Medical Climatology. London: MacMillan and Co., 1887, 21. ↩

-

Smith, F. C. The Relation of Climate to the Treatment of Pulmonary Tuberculosis. Public Health Bulletin 35. Washington: Government Printing Press, 1910, 5. ↩

-

Bryder, Linda. Below the Magic Mountain: A Social History of Tuberculosis in Twentieth-Century Britain. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1988. ↩