Introduction

Specimen Studies

0.1.1 | 0.1.2 | 0.1.3 | 0.1.4 | 0.1.5Methods

0.2.1 | 0.2.2The Structure of this Dissertation

0.3.1Tuberculosis' Visual Culture

Visual Practices in Medical Culture

1.1.1 | 1.1.2 | 1.1.3Seeing and Settling in the Sanatorium Movement

1.2.1 | 1.2.2 | 1.2.3 | 1.2.4 | 1.2.5Teaching Public Health

1.3.1 | 1.3.2 | 1.3.3 | 1.3.4 | 1.3.5Representing Doctors in Tuberculous Contexts

1.4.1 | 1.4.2Using Human Specimens in the Study of Tuberculosis

Seeing Disease in Methyl Violet

2.1.1 | 2.1.2 | 2.1.3 | 2.1.4Case Histories

2.2.1 | 2.2.2 | 2.2.3 | 2.2.4Visceral Processes

2.3.1 | 2.3.2Relation

2.4.1 | 2.4.2 | 2.4.3Arts-Based Inquiry

Introduction

3.1.1 | 3.1.2 | 3.1.3 | 3.1.4Terminal Imaginaries & Tuberculous Imaginaries

3.2.1 | 3.2.2 | 3.2.3 | 3.2.4 | 3.2.5 | 3.2.6Dermographic Opacities

3.3.1 | 3.3.2 | 3.3.3 | 3.3.4Tactical Pretensions

3.4.1 | 3.4.2 | 3.4.3Designing Opacity

A Shift towards the Anticolonial

4.1.1 | 4.1.2 | 4.1.3 | 4.1.4Refusals and Opacities

4.2.1 | 4.2.2 | 4.2.3 | 4.2.4Digital and Ethical Workflows

4.3.1 | 4.3.2 | 4.3.3 | 4.3.4 | 4.3.5Conclusion

4.4.1Coda

Prometheus Undone

5.1.1 | 5.1.2 | 5.1.3 | 5.1.4Appendix

The Tuberculosis Corpus

X.1.1 | X.1.2 | X.1.3Web Design

X.2.1 | X.2.2 | X.2.3 | X.2.4Installation Materials

X.3.1 | X.3.2 | X.3.3Index

In May 2022, I had the opportunity to develop a second installation using a similar three projector setup for the IFell gallery in Bloomington, Indiana.1 This project, Tuberculous Imaginaries, took advantage of a site specific approach,2 as well as an increased focus on the history of tuberculosis, which I had adopted as part of my dissertation project in Fall 2021. Much of my preliminary thinking regarding tuberculosis’ visual culture were derived while working on this installation (1.1.2; 2.2.2).

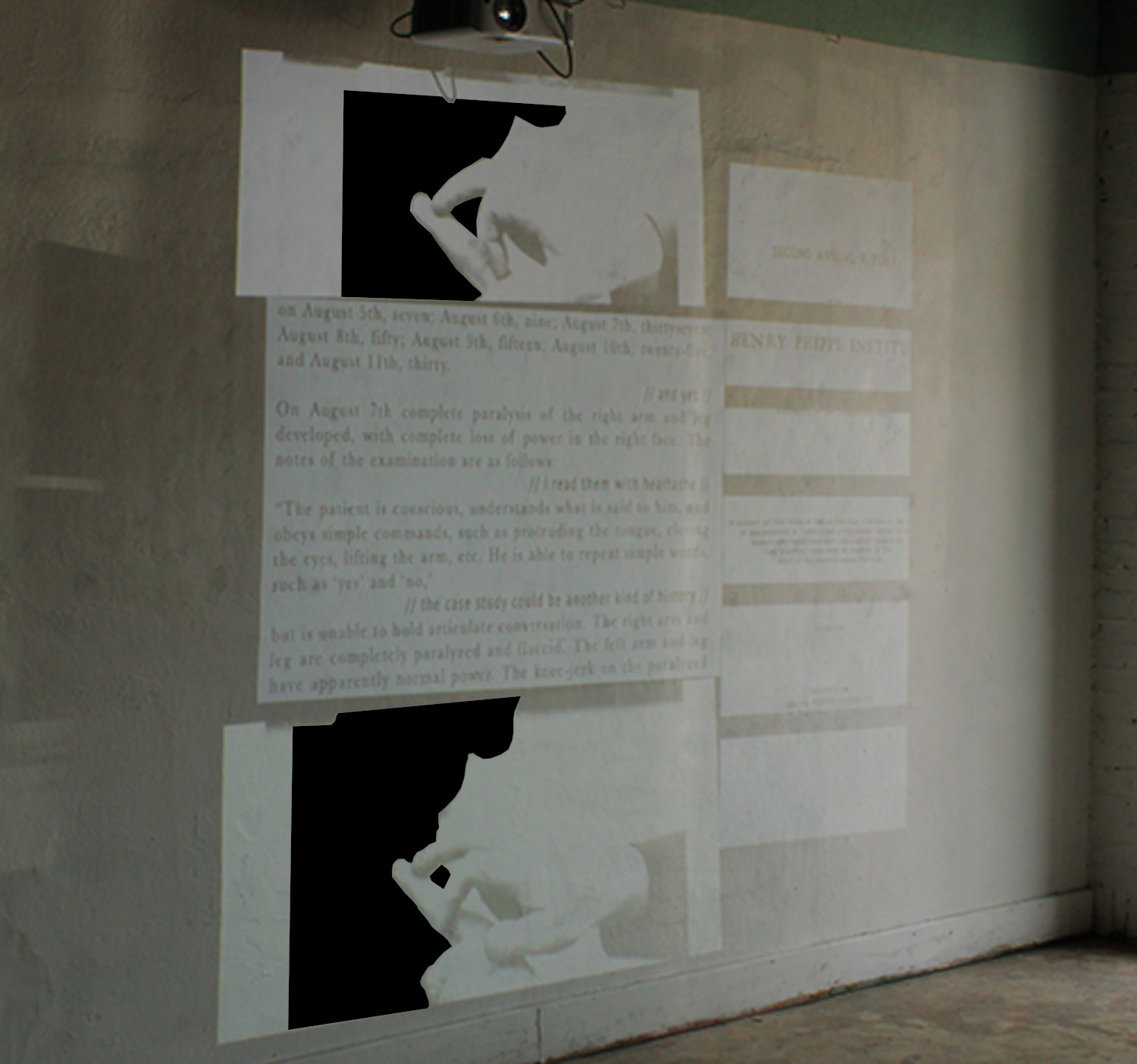

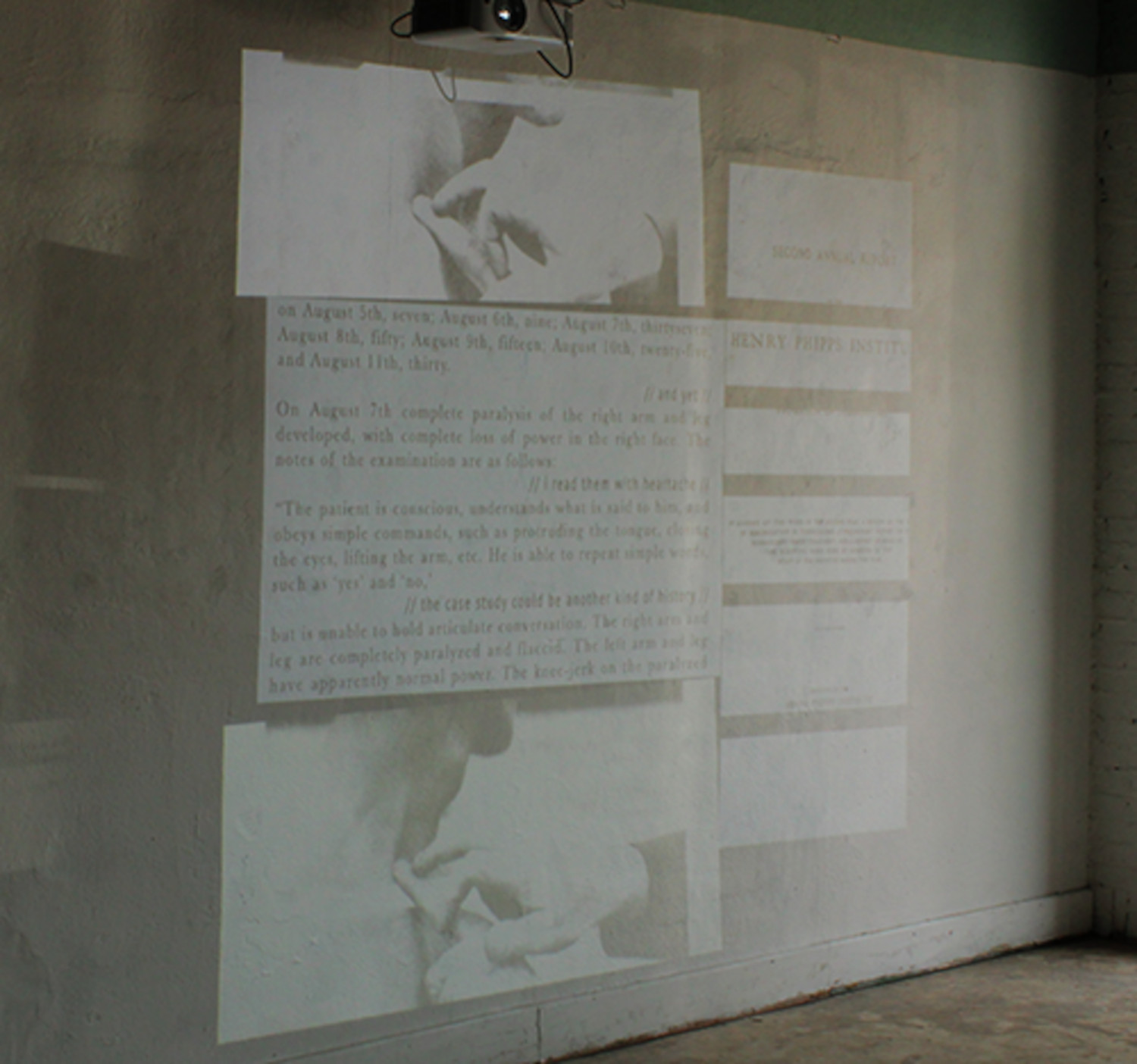

With three projectors and two walls, Tuberculous Imaginaries used a similar overlapping projector schema for one wall and a single second projector for the other (figs. 1 - 3), and each video feed displayed a specifically curated set of objects from the tuberculosis corpus (X.1.1). For this installation I attempted to take advantage of an affordance of digital projection: the potential for an uninterrupted durational video feed. I used this to create three videos of differing lengths, which would then project in unique ways over the course of the month-long installation. All of the images were made using materials from the tuberculosis corpus (X.1.1), but I only selected images from twenty-nine sources.3 A more thorough description of the method of each projector can be found in the appendix (X.3.1).

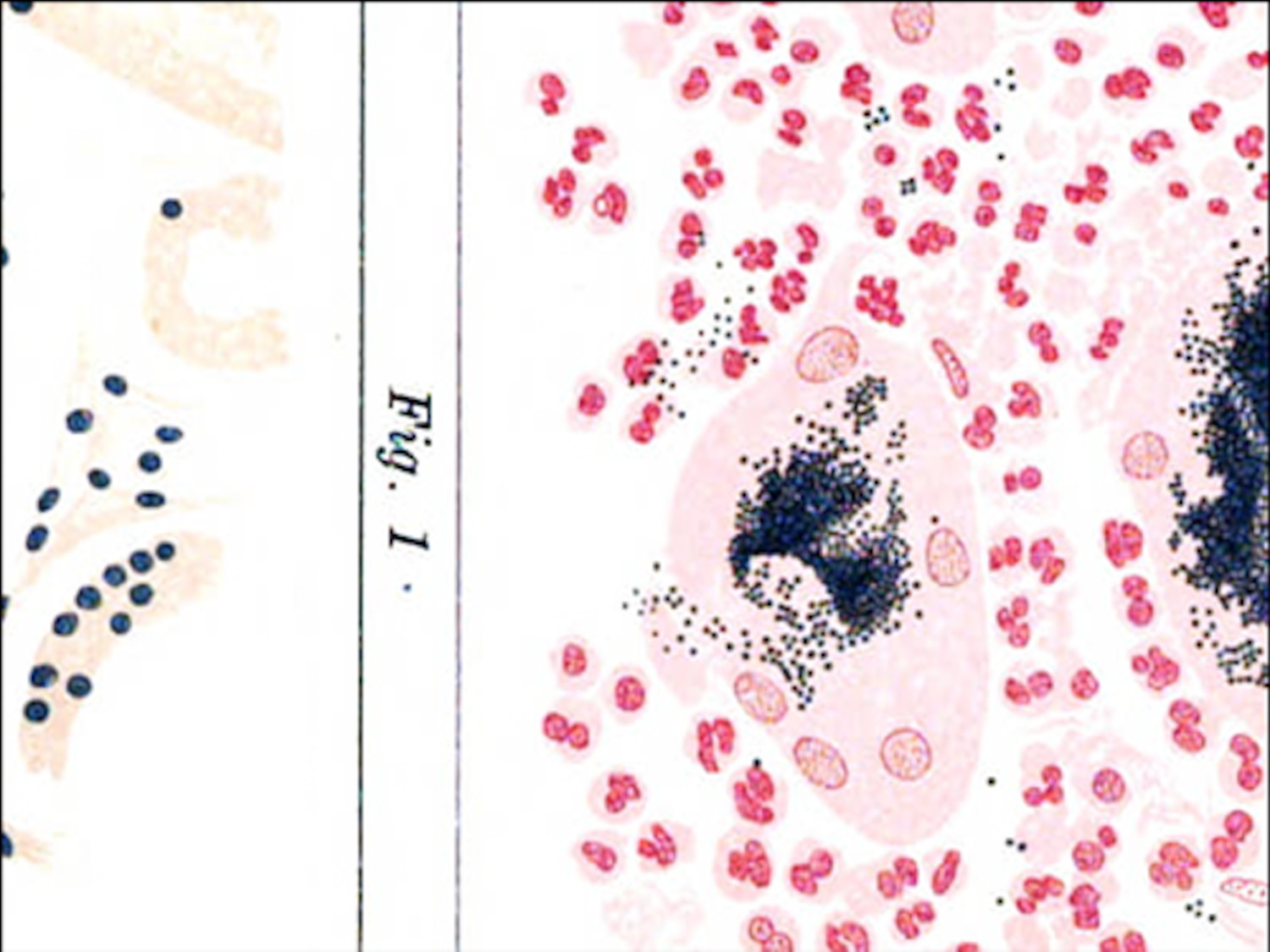

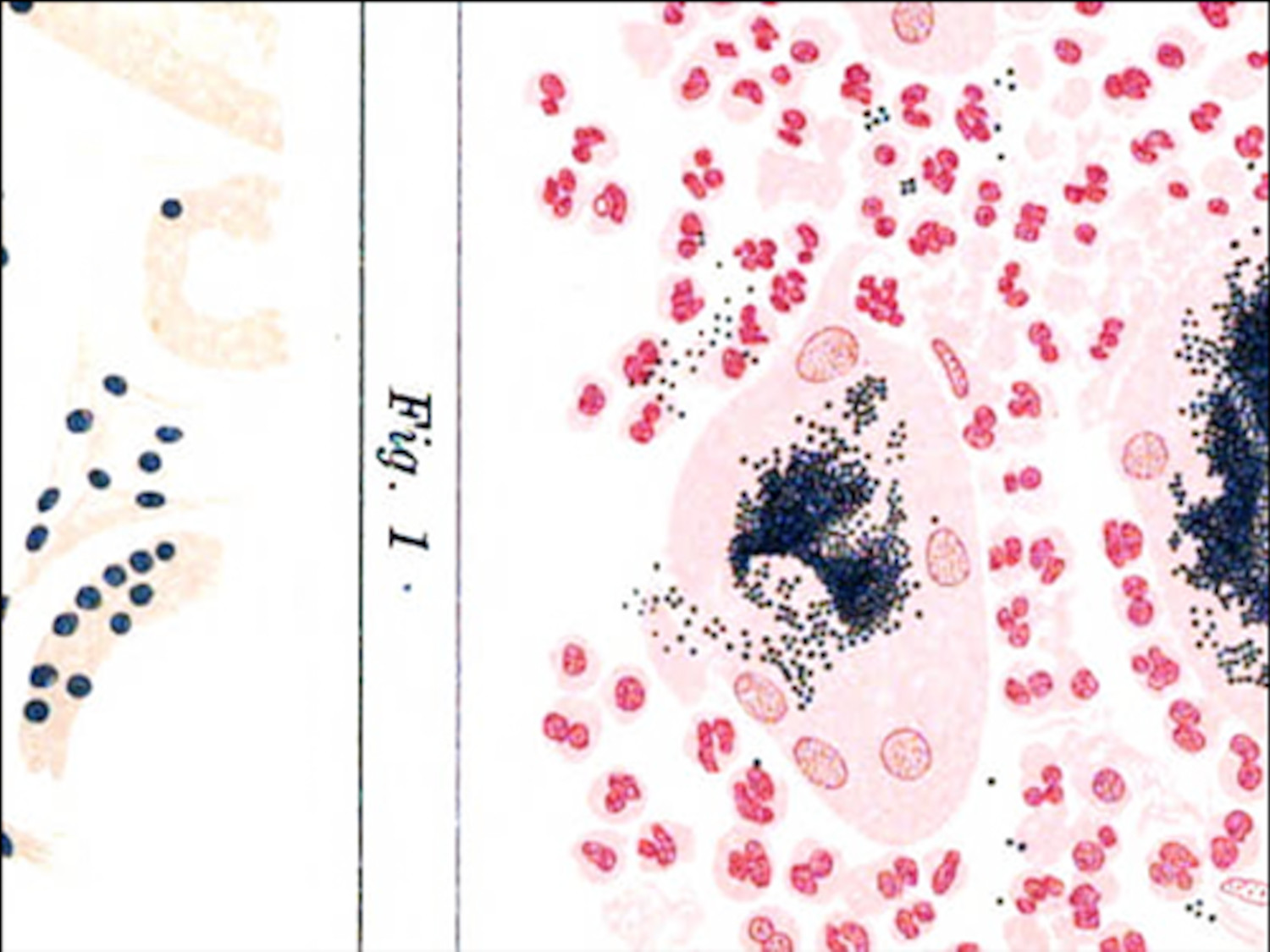

Projector A stood on its own, projecting onto the east wall of the IFell’s gallery space. It showed pathological illustrations and clinical photographs (2.2.2) and displayed these images with long durational zooms on the still frame. For the most part, I chose images that might look closer to an abstract composition (figs. 4), but in a few cases I kept figural images in tact (fig. 5).4

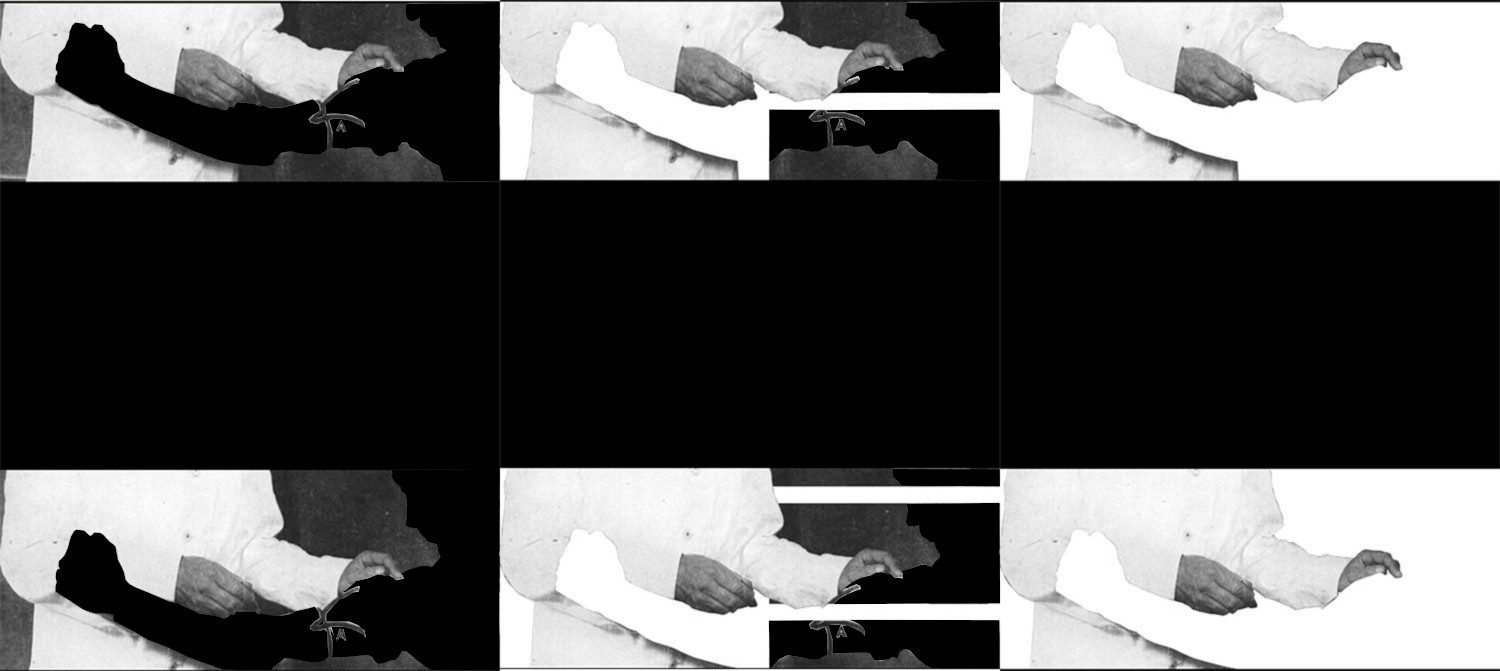

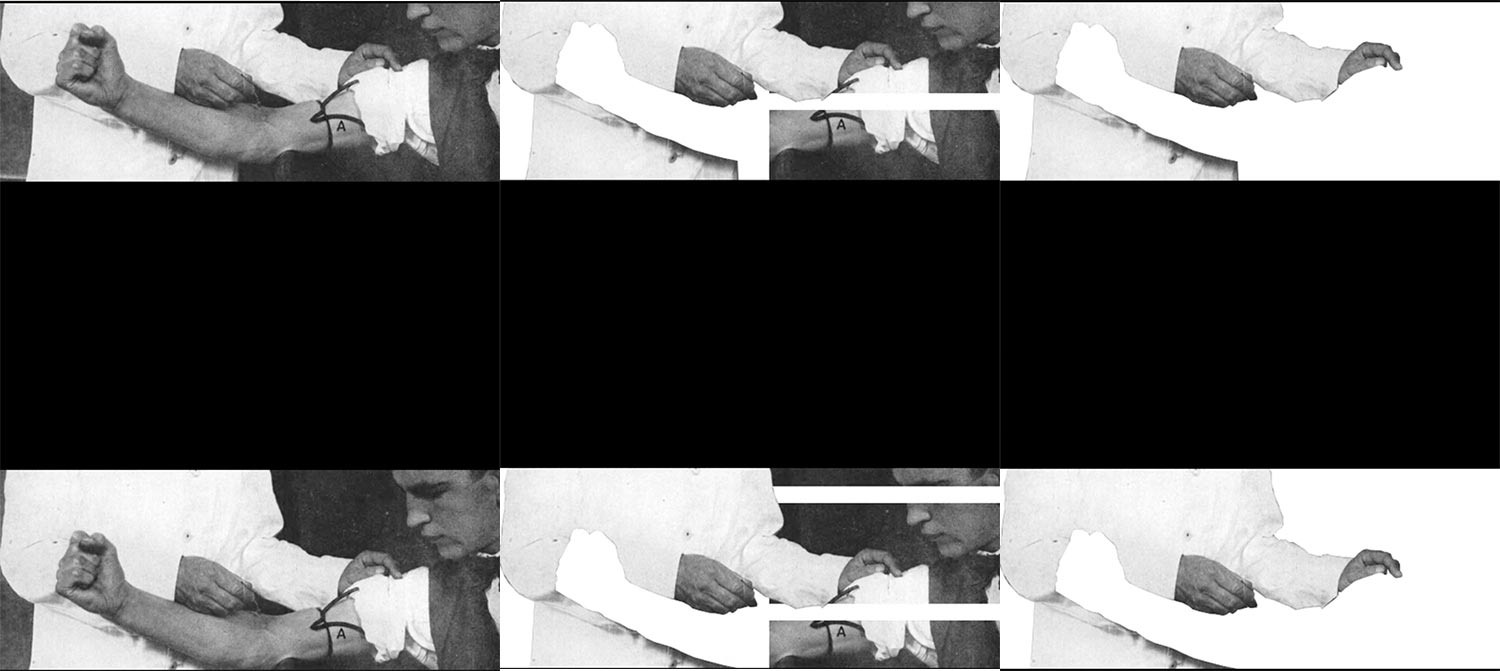

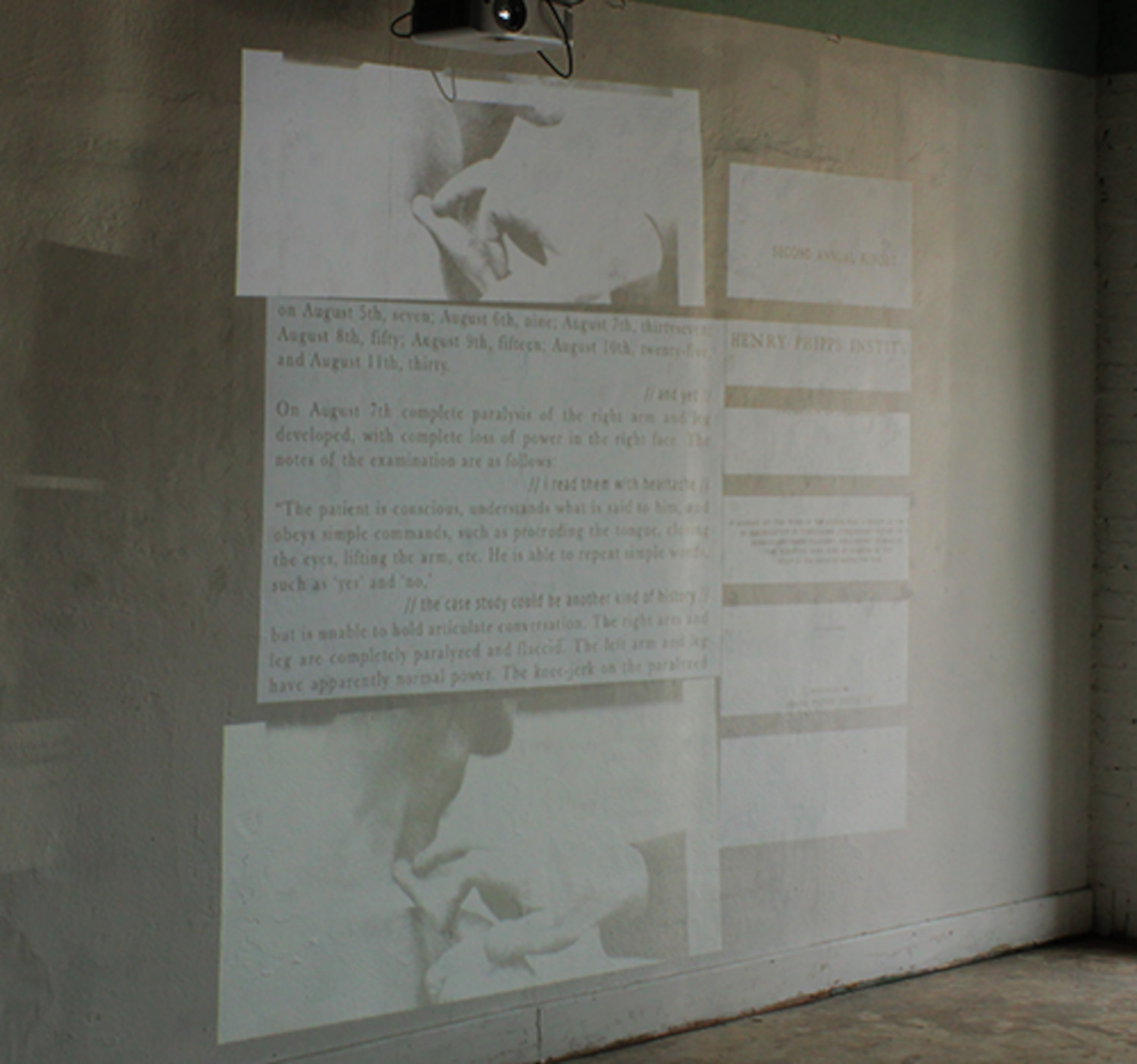

Projector B showed images of doctors and other medical professionals. One of the things I began to think about after completing Terminal Imaginaries (3.2.1) and “Dermographic Opacities” (3.3.1) was the way doctors were less prominent in clinical photographs. Sometimes only the hands of the doctor would be in view, and other times one could only see some other restraining apparatus, and I began to wonder about how the medical professionals may be visible in the frame (1.4.1; 1.4.2). To examine the ways this disciplinary visual practice unfolded, I took photographs from the selected text that had medical professionals in the frame, cut out multiple layers of the image, and animated the erasure of any foreground and background, making the doctors the subjects (fig. 7).

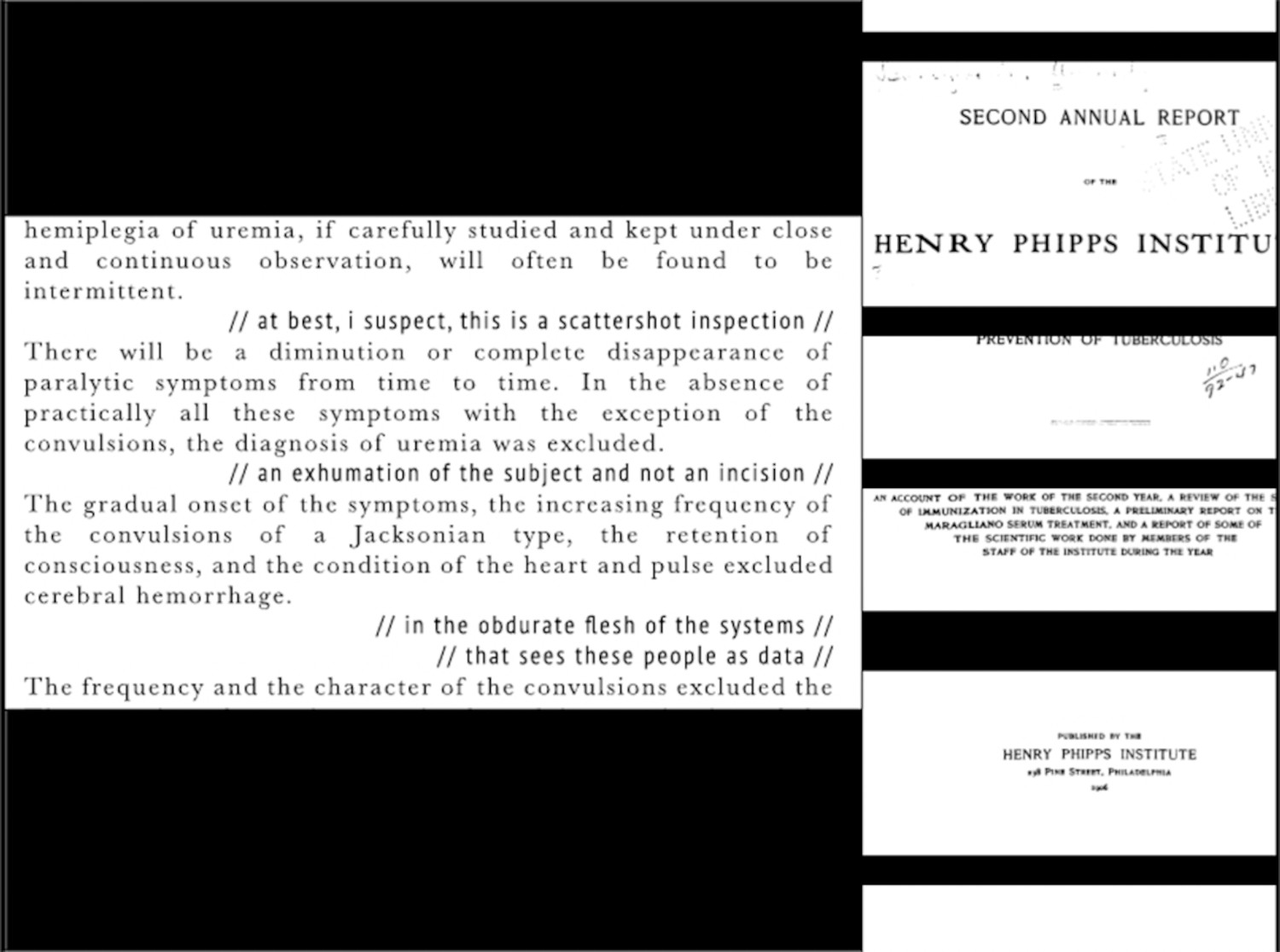

Projector B was a unique install, because it was displayed in a portrait style setup.5 For this video feed, all of the images were produced for the top and bottom of the image, allowing a second video feed from Projector C to be projected through. This feed displayed text from a few chapters of the primary sources, as well as written commentary; the cover of the source was also projected (figs. 7 & 8) (X.3.2; X.3.1). As I wrote on the project’s website, “[r]ather than enshrine these artifacts as authoritative, concrete specimens, I have taken care to respond to and reflect on the rhetoric employed by medical professionals in their discourses between other scientists and the public.”6 I used this video feed as an opportunity to read some of the primary materials and try to comment on their assumptions.

-

A few thanks are in order for this specific installation. I am indebted to the help of Sydney Stutsman, who helped with the final build, as well as to the entire staff at the Institute for Digital Arts and Humanities—Kalani Craig, Michelle Dalmau, Vanessa Elias, and Pouyan Shahidi. ↩

-

Kwon, Miwon. One Place after Another: Site Specific Art and Locational Identity. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2004; Mondloch, Kate. “Be Here (and There) Now: The Spatial Dynamics of Screen-Reliant Installation Art.” Art Journal 66, no. 3 (2007): 20–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/00043249.2007.10791263; Mondloch, Kate. Screens: Viewing Media Installation Art. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010. ↩

-

A full list can be found at the installation’s website. ↩

-

I do not know why I kept the last image, because for the most part, I attempted to keep the subjects anonymous. I think I felt at the time that the face was obscure enough, abstract enough to be anonymized. My thinking regarding anonymity has changed quite a bit in the years since its completion. ↩

-

One of the biggest problems I encountered, and which Sydney, wo assisted with the install, and I had to address was that the projector, nor the mount were made for this setup. The result was a bit less than professional, with a vaugely ninety degree angle tilt, and issues with the projected frame being distorted. ↩

-

Sean Purcell. “Tuberculous Imaginaries: Artist Statement”. (May, 2022). https://tuberculousimaginaries.github.io/Installation/ ↩