Introduction

Specimen Studies

0.1.1 | 0.1.2 | 0.1.3 | 0.1.4 | 0.1.5Methods

0.2.1 | 0.2.2The Structure of this Dissertation

0.3.1Tuberculosis' Visual Culture

Visual Practices in Medical Culture

1.1.1 | 1.1.2 | 1.1.3Seeing and Settling in the Sanatorium Movement

1.2.1 | 1.2.2 | 1.2.3 | 1.2.4 | 1.2.5Teaching Public Health

1.3.1 | 1.3.2 | 1.3.3 | 1.3.4 | 1.3.5Representing Doctors in Tuberculous Contexts

1.4.1 | 1.4.2Using Human Specimens in the Study of Tuberculosis

Seeing Disease in Methyl Violet

2.1.1 | 2.1.2 | 2.1.3 | 2.1.4Case Histories

2.2.1 | 2.2.2 | 2.2.3 | 2.2.4Visceral Processes

2.3.1 | 2.3.2Relation

2.4.1 | 2.4.2 | 2.4.3Arts-Based Inquiry

Introduction

3.1.1 | 3.1.2 | 3.1.3 | 3.1.4Terminal Imaginaries & Tuberculous Imaginaries

3.2.1 | 3.2.2 | 3.2.3 | 3.2.4 | 3.2.5 | 3.2.6Dermographic Opacities

3.3.1 | 3.3.2 | 3.3.3 | 3.3.4Tactical Pretensions

3.4.1 | 3.4.2 | 3.4.3Designing Opacity

A Shift towards the Anticolonial

4.1.1 | 4.1.2 | 4.1.3 | 4.1.4Refusals and Opacities

4.2.1 | 4.2.2 | 4.2.3 | 4.2.4Digital and Ethical Workflows

4.3.1 | 4.3.2 | 4.3.3 | 4.3.4 | 4.3.5Conclusion

4.4.1Coda

Prometheus Undone

5.1.1 | 5.1.2 | 5.1.3 | 5.1.4Appendix

The Tuberculosis Corpus

X.1.1 | X.1.2 | X.1.3Web Design

X.2.1 | X.2.2 | X.2.3 | X.2.4Installation Materials

X.3.1 | X.3.2 | X.3.3Index

The examples from the British Journal of Tuberculosis and Brandt’s directory, as well as the emphasis on architecture’s facilitation of healing, display a common set of assumptions around how to care for those with tuberculosis (1.2.3). The emphasis on the buildings, structures, and environments for patients correspond with assumptions about how health can be managed in controlled spaces. The method of curing the sick in this discourse is associated more closely with a property investment and land development, rather than the actual processes of the rest cure or any surgical intervention.

With that in mind, I want to end this case study with a closer look at two sanatoria which were built at the turn of the twentieth century in Colorado: the Cragmor Sanatorium and the National Jewish Hospital for Consumptives (NJHC). Both were constructed from a desire to address a local and national need for patients with tuberculosis, but both went about creating their facilities in very different ways. I use these sanatoria as examples of how these health institutions built around ideas of community support and charity. The two institutions were driven by very different funding models, but both were guided a desire to build a cure, and saw their institutions expand at a similar pace in the first decades of the twentieth century.

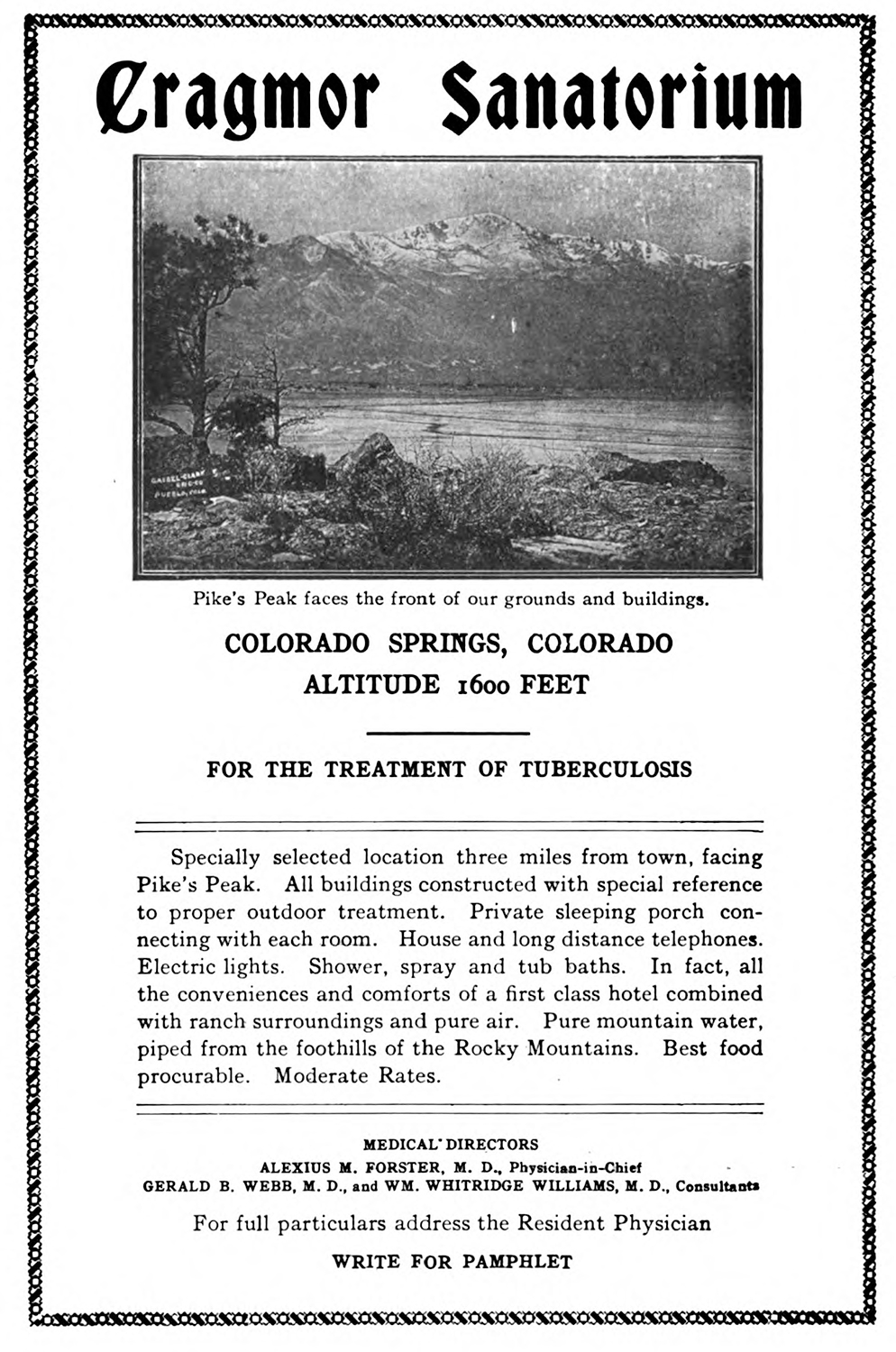

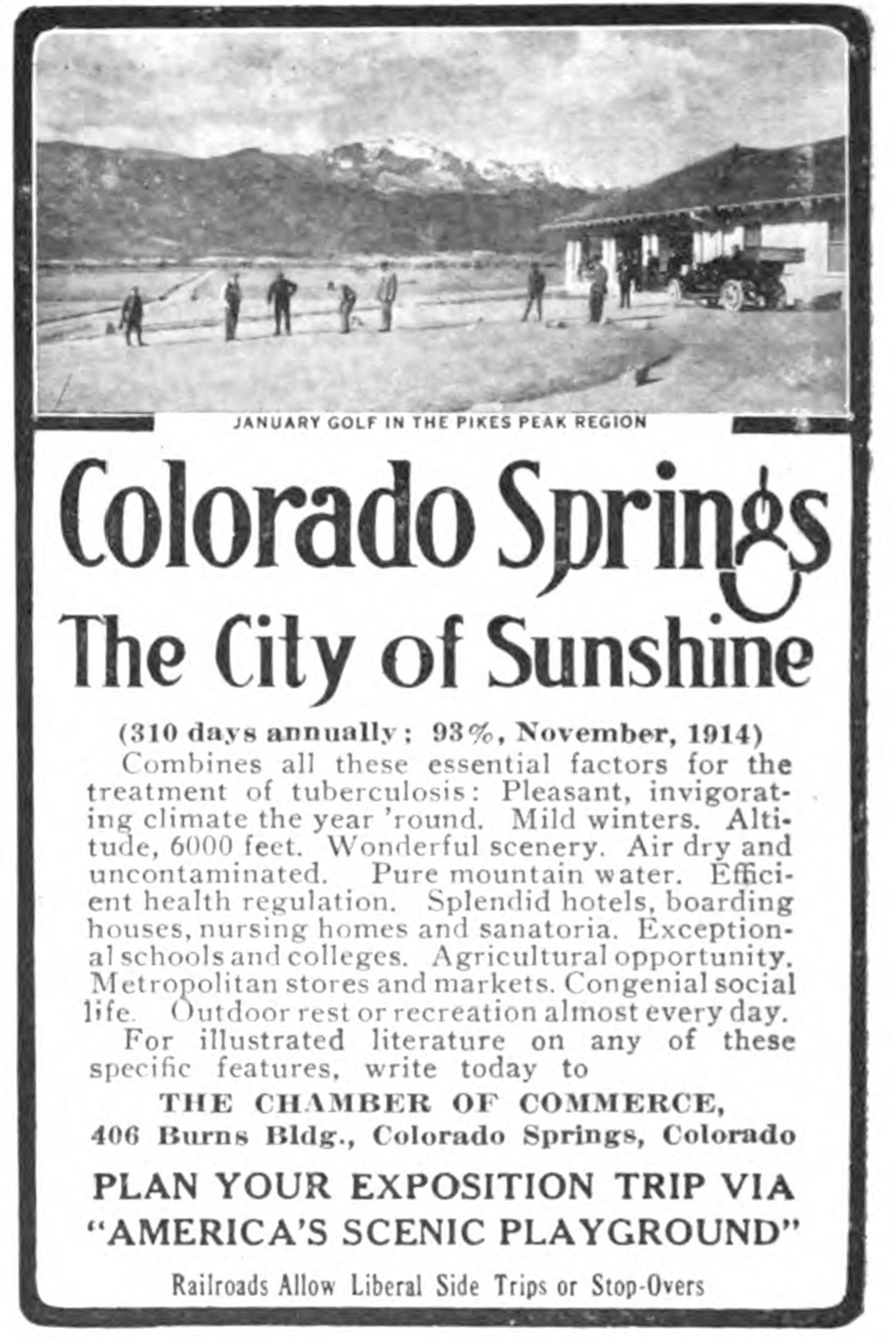

Built on a bluff overlooking Colorado Springs, the Cragmor Sanatorium (fig. 1) was originally meant to be much larger. Cragmor was the brainchild of a British doctor, Edwin Solly, who travelled to the Rocky Mountain’s eastern slope to cure the tuberculosis infections of both himself and his wife. Solly imagined Cragmor as a palatial campus, that would bring prominence to the growing city, itself trying to advertise as a destination for patients with tuberculosis (fig. 2). As Douglas R. McKay argues in his history of Cragmor, it was doctors that pushed for its construction: “The medical society then voted overwhelmingly to endorse Solly’s proposal, choosing to build first for the wealthy, then from the profits subsidize a later edifice designed for the poor.”1

This nineteenth-century fever dream never realized, owing to the outsized costs of erecting the planned structure. Thomas MacLaren, the architect hired for the initial construction, designed the original plan around a central building—“the Sun Palace”—that enabled patients to lounge in direct sunlight at all times during the day: “the dining rooms, designed to occupy the whole of the first and second floors of the southeast wing, were so arranged that three sides could be thrown open to the outside.”2 While MacLaren would design other sanatoria, his and Solly’s original designs never came to fruition, owing to an estimated $300,000 - $350,000 cost to construct the opulent main palace. When the sanatorium did open its doors on June 20th, 1905, its more modest campus was composed of two main buildings, two pavilions with eight suites, and eight single room cabins that lined the spine of bluff.3

Cragmor would, over the first half of the twentieth century, become a relatively prominent tuberculosis sanatorium. While Solly passed away in 1906, Cragmor grew over the first half of the twentieth century, with Alexius M. Forster and Gerald Webb taking the reins over the next decades.4 Solly’s idealistic, glamorous vision for a sanatorium matched an aesthetic that catered to a well-to-do clientele. It was meant to be a healing resort, and its target audience corresponded with the images of healing seen in Davos (1.2.2). The architectural fervor which guided the extravagant initial plans echo the space-as-remedy approach many doctors and institutions took to address the disease (1.2.3). More importantly, the sanatorium was something that could, and should, be built with specific structural considerations in mind, and its construction served as an anchor for both the medical profession, as well as a feather in the cap of a growing city, aspiring to be a hub of culture and industry.

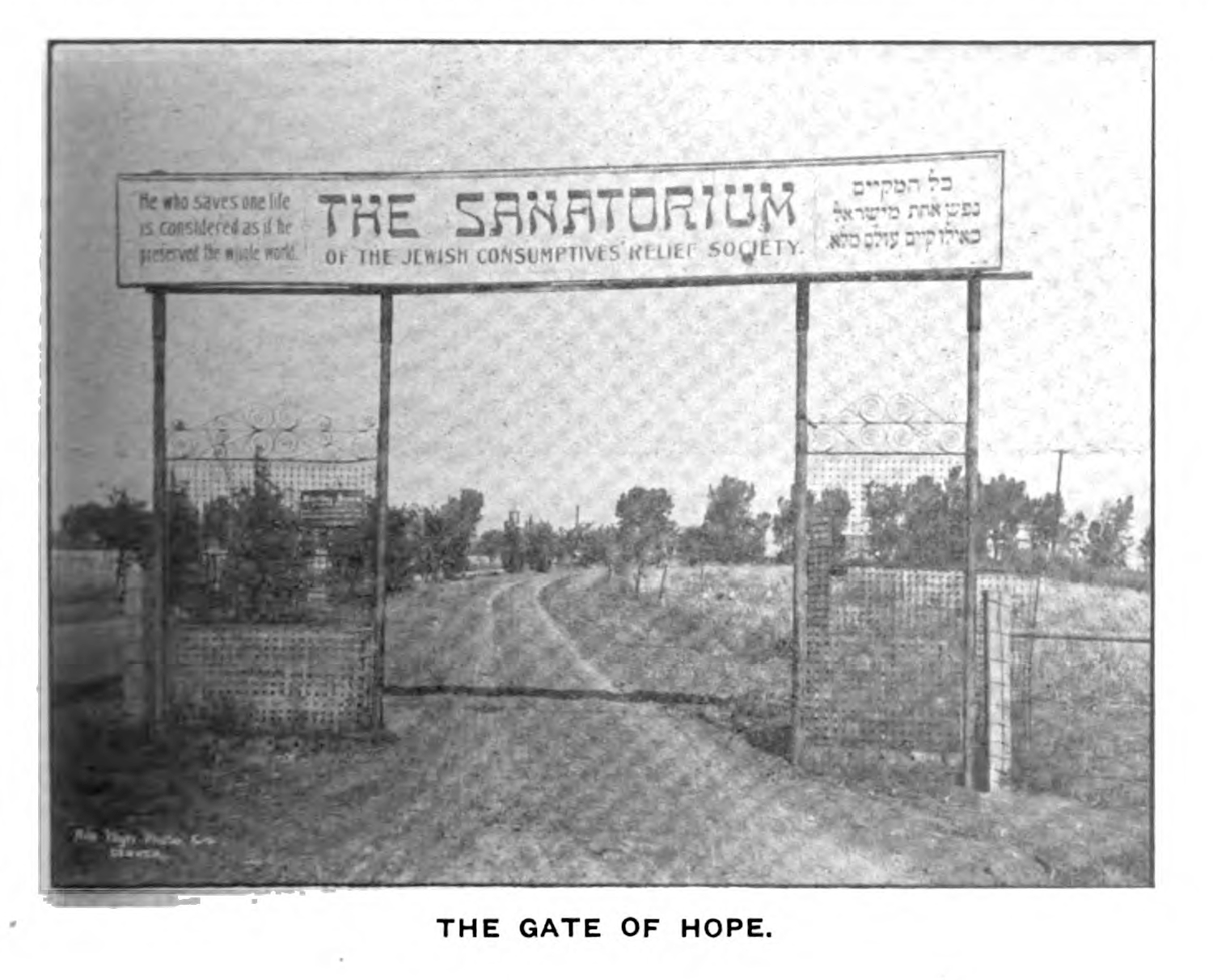

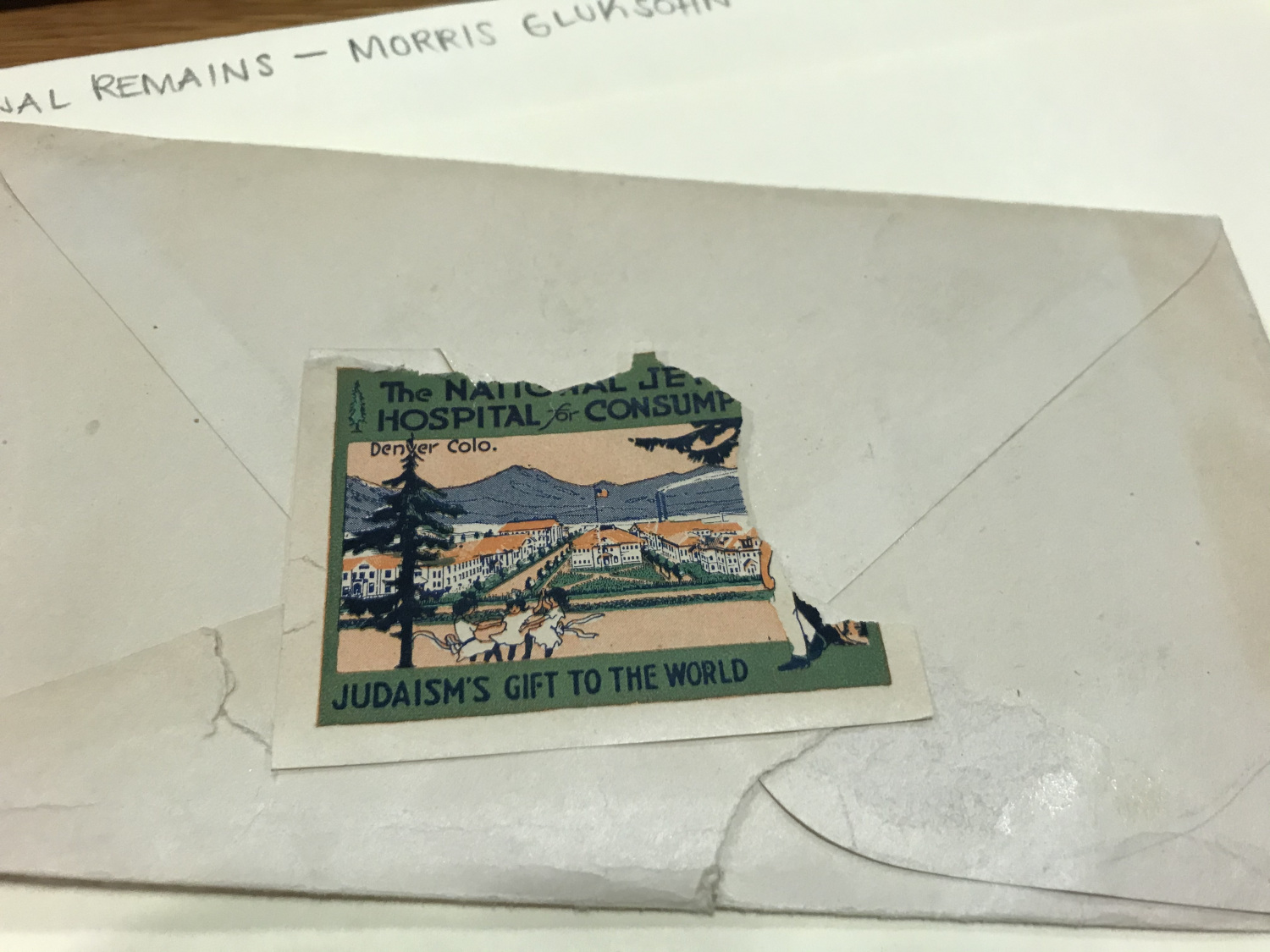

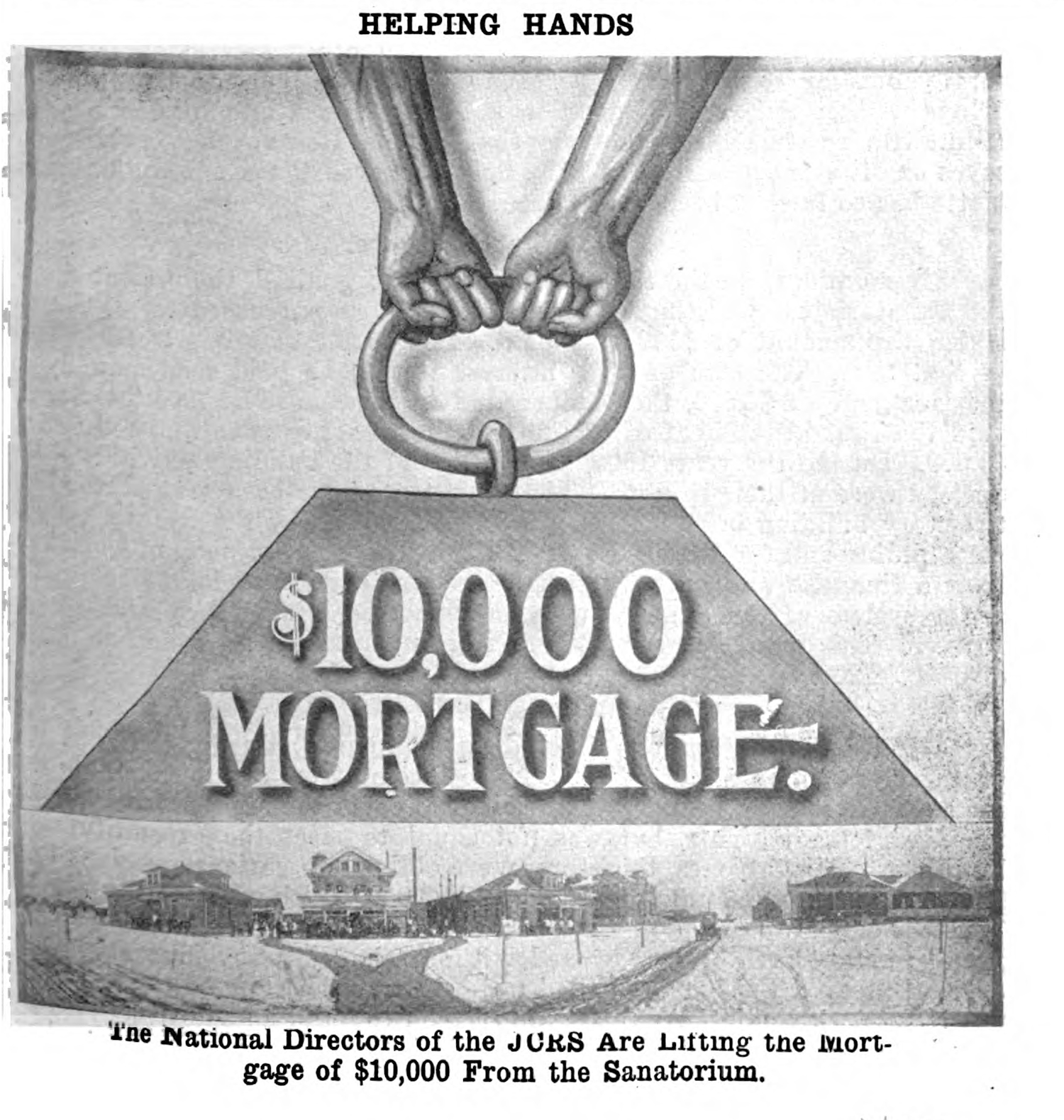

Roughly sixty miles north of Cragmor and established six years prior to Solly’s sanatorium, the National Jewish Hospital for Consumptives (NJHC) opened its doors to care for the nation’s consumptive poor. It and its sister institution, the National Jewish Consumptive Relief Society (NJCRS), operated entirely on donations provided by Jewish communities and individuals across the nation.5 The anti-tuberculosis institutions were formed as one of many charities in the Denver region. Its existence was owed to one of many approaches to charity in the Jewish faith, as Rabbi C. E. Hillel Kauvar described in a speech given in 1912: “The giving of alms is a compulsory act, it is more than a free will gift; it is a matter of an obligation, of justice. We are our brothers’ keepers. We are responsible one for the other.”6 This emphasis on obligation was reiterated through the use of a Jewish proverb which was used to describe the institution’s project—“He who saves one life is considered as if he had preserved the whole world” (fig. 3)—while also framing the institution as a gift (fig. 4).

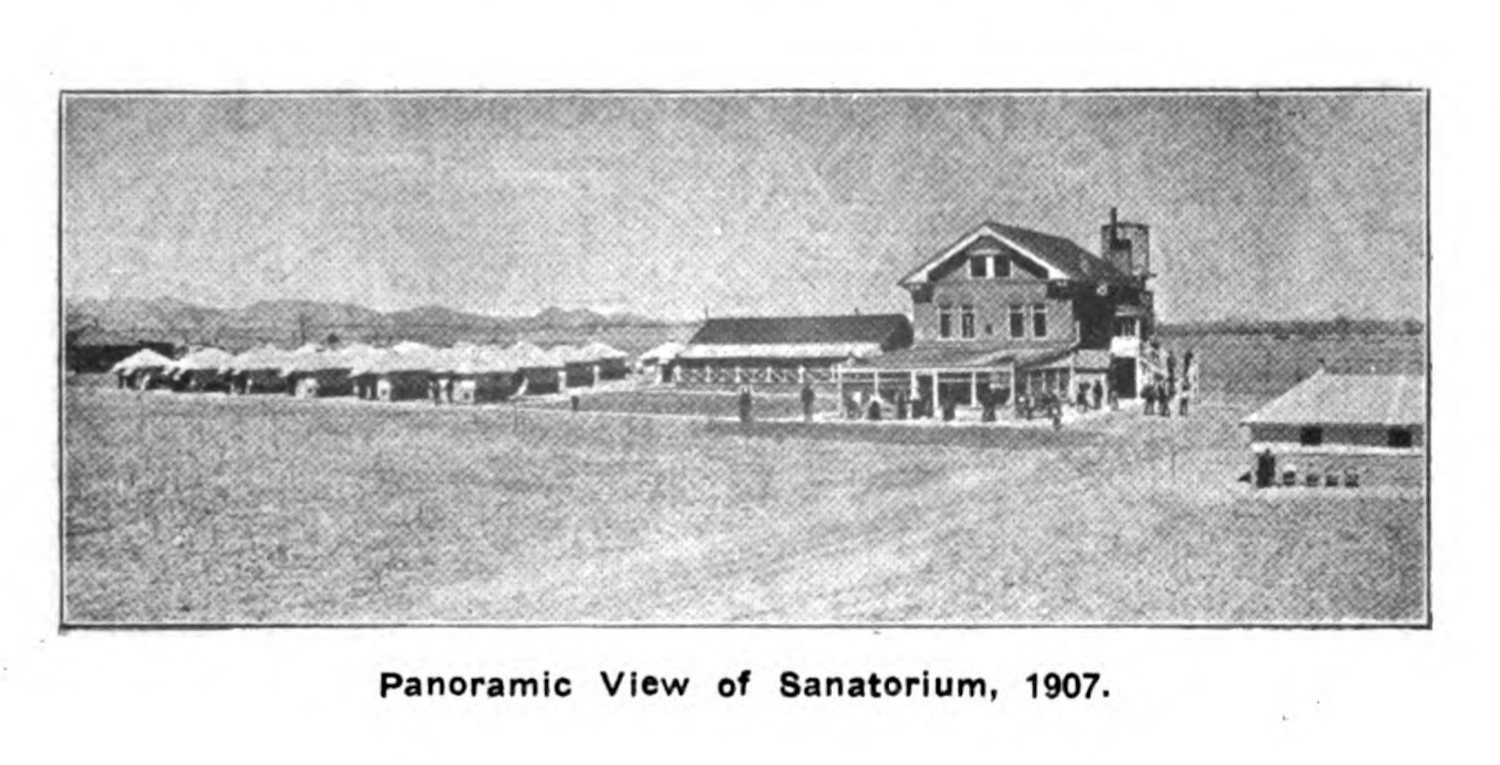

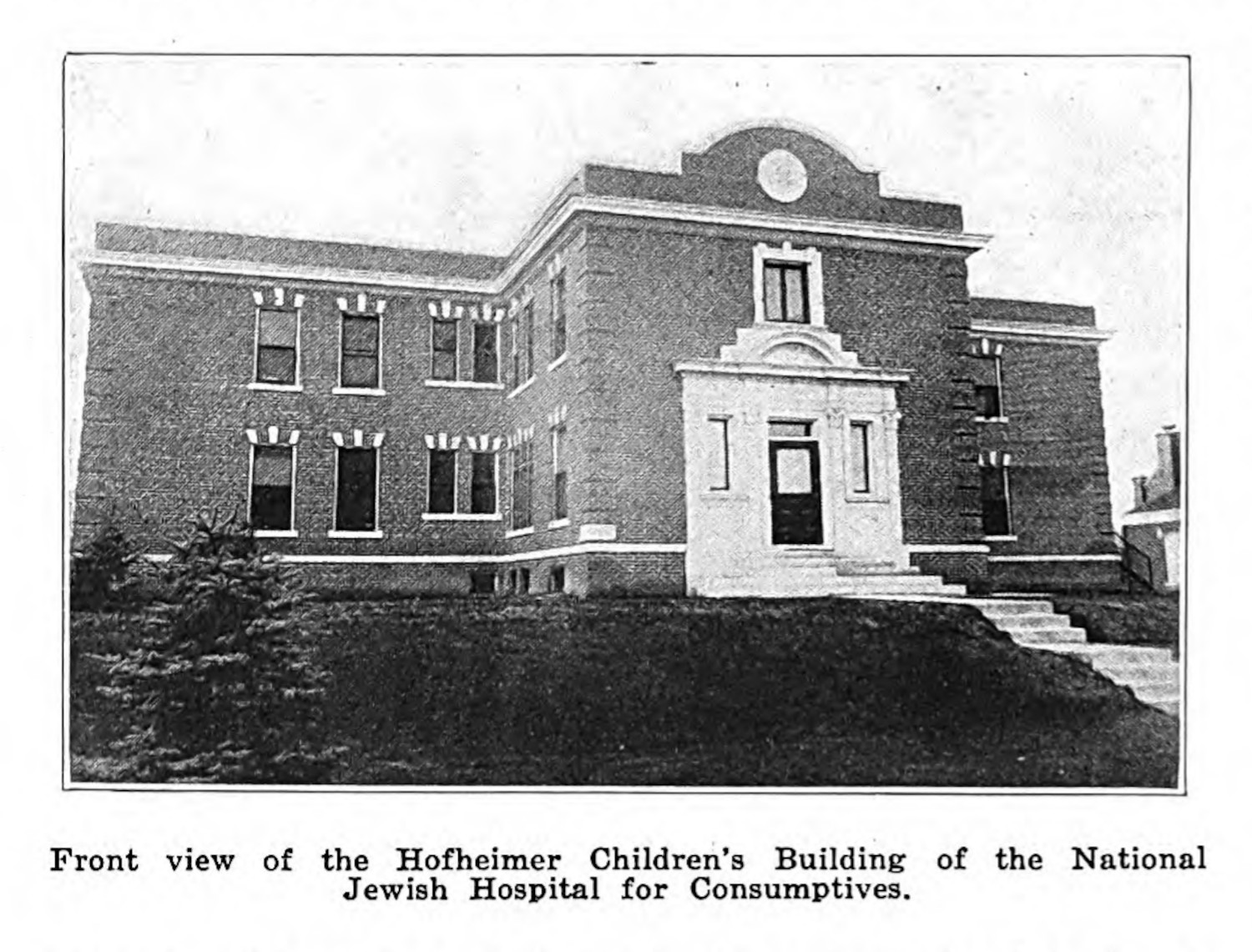

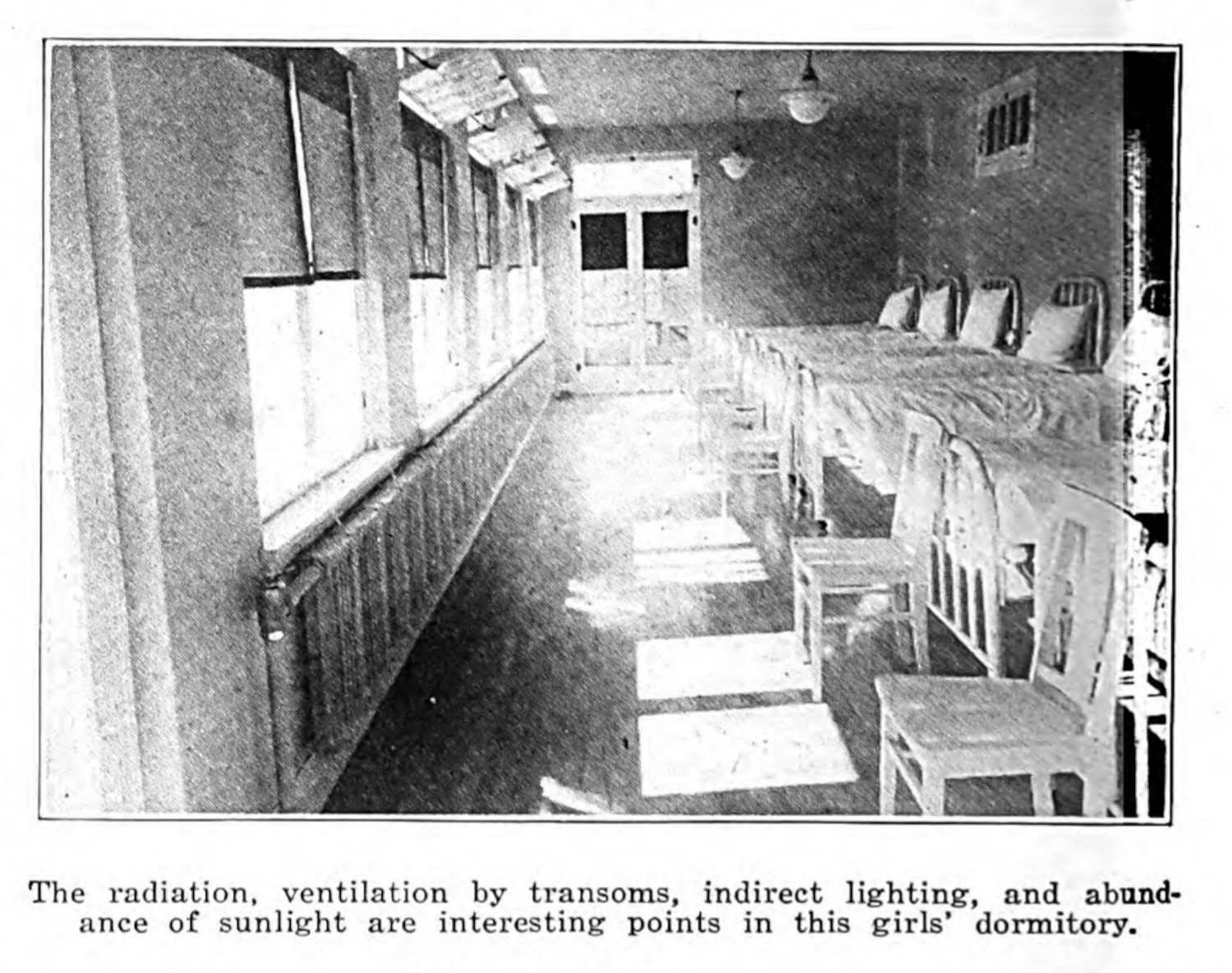

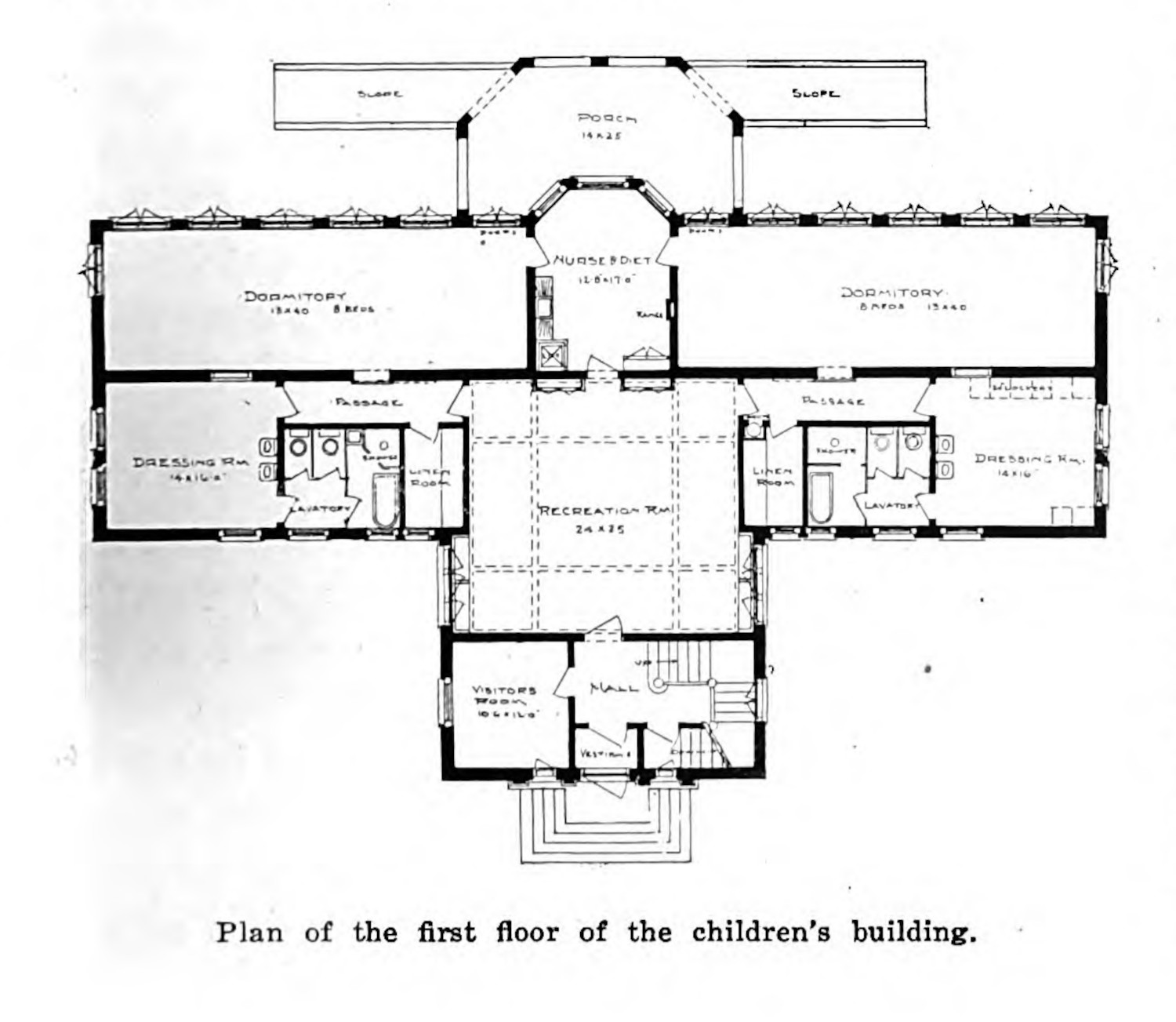

Unlike Cragmor, the NJHC grew its operations over the years, starting with a compound of semi-permanent tents (fig. 5). Tent structures were commonly used by institutions and private consumers as a way to provide open air access throughout the year. The Jewish organization used these temporary structures to care for patients while they were in the process of constructing permanent facilities (figs. 5 - 7). The NJHC purchased land in Denver in 1904, and over the next four years developed a massive funding deficit, which the organization addressed a decade later (fig. 8).7 Over the next twenty years, the sanatorium continued to serve patients and grow, erecting eleven new buildings. In 1914 the NJHC constructed a medical testing facility—the Grabfelder building—which held administrative offices, laboratory rooms, diagnostic suites, a fully equipped x-ray department, and housing for testing animals;8 and in 1921, they erected a large building for children with tuberculosis (figs 9 - 11).

In each of these examples, the construction of new buildings corresponded with an expansion of care: more patients could be treated, more facilities could allow for different medical specialties, and more research could be practiced for the betterment of people in the future. New buildings, in this context, represented an extension of the obligation to care for patients.

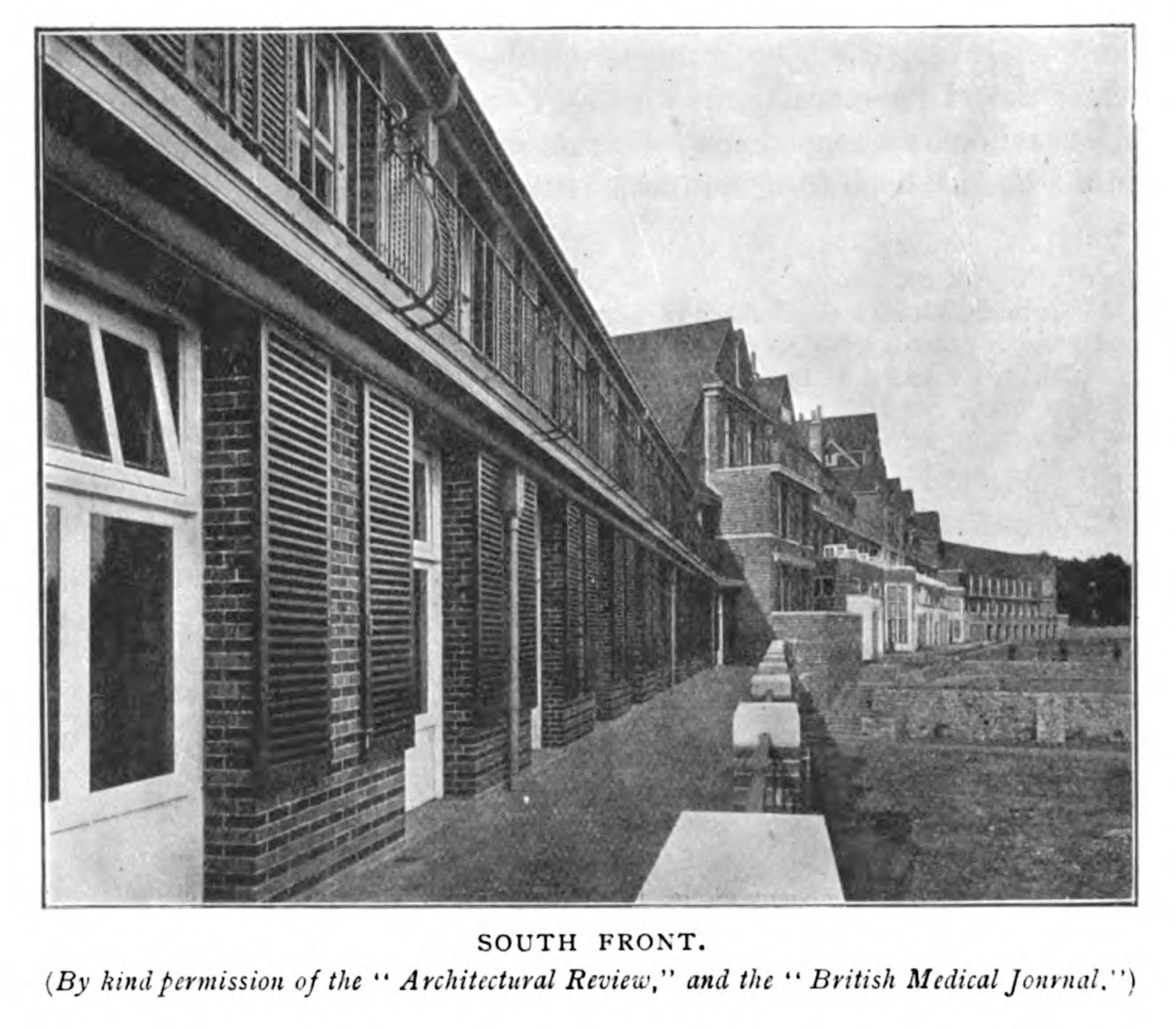

Both the NJHC and the Cragmoor Sanitarium present a capitalistic logic underneath the will to care. I do not mean in the monopolistic or industrial mechanisms of the gilded age in which these institutions were first built, nor the current late-capitalist, privatized medical hellscape which defines our current health system;9 instead, I mean it in the very basic principle of capital, where owned resources can be leveraged for increased output and gain. I stress this notion of investment, because in many ways the photographs and floor plans of the sanatorium displayed earlier in this chapter show health as a secondary interest to architectural aesthetics (1.2.3). The photographs that were reproduced for the King Edward VII Sanatorium were originally printed in two different contexts: an architectural review and a medical journal (figs. 12 & 13) (1.2.3). The sanatorium, like a hospital, invested the funds into an infrastructure that could be further leveraged, either toward the care of patients or for the continued profit of the actors who owned it.10 Both the Cragmor Sanatorium and the NJHC were guided by a different approaches to social change and the care for the sick, and both institutions treated patients while also building on and expanding on the land owned by the organization. In both cases, the investments were made in earnest and undergirded by a principle that the space and location of the care would benefit their patients. The capital projects expanded the capacity to treat more patients, and the additional byproducts were leveraged by successive generations, various shifts in leadership, and changes in the nation’s healthcare system.11

-

McKay, Douglas R. The Asylum of the Gilded Pill: The Story of Cragmor Sanatorium. State Historical Society of Colorado, 1983. 20. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid., 28-29. ↩

-

Both of these doctors feature prominently in the tuberculosis dataset developed for this dissertation. Gerald Webb, was especially prolific, being an author or co-author on 44 publications across the corpus. ↩

-

Where the NJHC required admission, with patients selected at the digression of the hospital’s staff, the NJCRS accepted any and all patients, some of whom were so sickly that they died within twenty-four hours of their admission. ↩

-

C. E. Hillel Kauvar. “The Jewish Conception of Charity: Shall the Denver Jews Federate Their Charities?” The Sanitorium 7(1). 1913. 6. ↩

-

“The History of the $10,000 Mortgage” The Sanitorium 8(2). 1914. 37. ↩

-

“Foundation of Grabfelder Building”. Jewish Charities: Bulletin of National Conference of Jewish Charities 4(12). (Baltimore: 1914), 2. ↩

-

And I also am remiss to note that the use of Marxist analysis is especially troubling, given Marx’s overt antisemitism. I associate this kind of capital accumulation more closely with American expansionism and exceptionalism which is present in medical development that includes but is far more prevalent throughout the medical establishment, and not just the NJHC (1.2.5). ↩

-

NJHC still exists, as National Jewish, and the facilities are linked to a robust lung care center in the heart of Denver. While the organization is completely different than that imagined by the National Jewish Consumptive Relief Society, its investments remain. Cragmoor, similarly, leveraged both professional and material capital through successive transformations from sanatorium, to nursing program, to an auxillary campus of the University of Colorado system. ↩

-

It is important to note that these organizations were absorbed into larger conglomerates: Cragmor into the University of Colorado System, and the National Jewish Hospital for Consumptives eventually becoming National Jewish Health. These organizations have very different desires and uses for the institutions they had been or the institutions they absorbed.

An interesting note too is that while the NJHC and Cragmor Sanitorium both contain extant buildings, just as many sanatoria, like the Pottenger Sanitorium in Monrovia, California, from the period no longer have any extant buildings. ↩