Introduction

Specimen Studies

0.1.1 | 0.1.2 | 0.1.3 | 0.1.4 | 0.1.5Methods

0.2.1 | 0.2.2The Structure of this Dissertation

0.3.1Tuberculosis' Visual Culture

Visual Practices in Medical Culture

1.1.1 | 1.1.2 | 1.1.3Seeing and Settling in the Sanatorium Movement

1.2.1 | 1.2.2 | 1.2.3 | 1.2.4 | 1.2.5Teaching Public Health

1.3.1 | 1.3.2 | 1.3.3 | 1.3.4 | 1.3.5Representing Doctors in Tuberculous Contexts

1.4.1 | 1.4.2Using Human Specimens in the Study of Tuberculosis

Seeing Disease in Methyl Violet

2.1.1 | 2.1.2 | 2.1.3 | 2.1.4Case Histories

2.2.1 | 2.2.2 | 2.2.3 | 2.2.4Visceral Processes

2.3.1 | 2.3.2Relation

2.4.1 | 2.4.2 | 2.4.3Arts-Based Inquiry

Introduction

3.1.1 | 3.1.2 | 3.1.3 | 3.1.4Terminal Imaginaries & Tuberculous Imaginaries

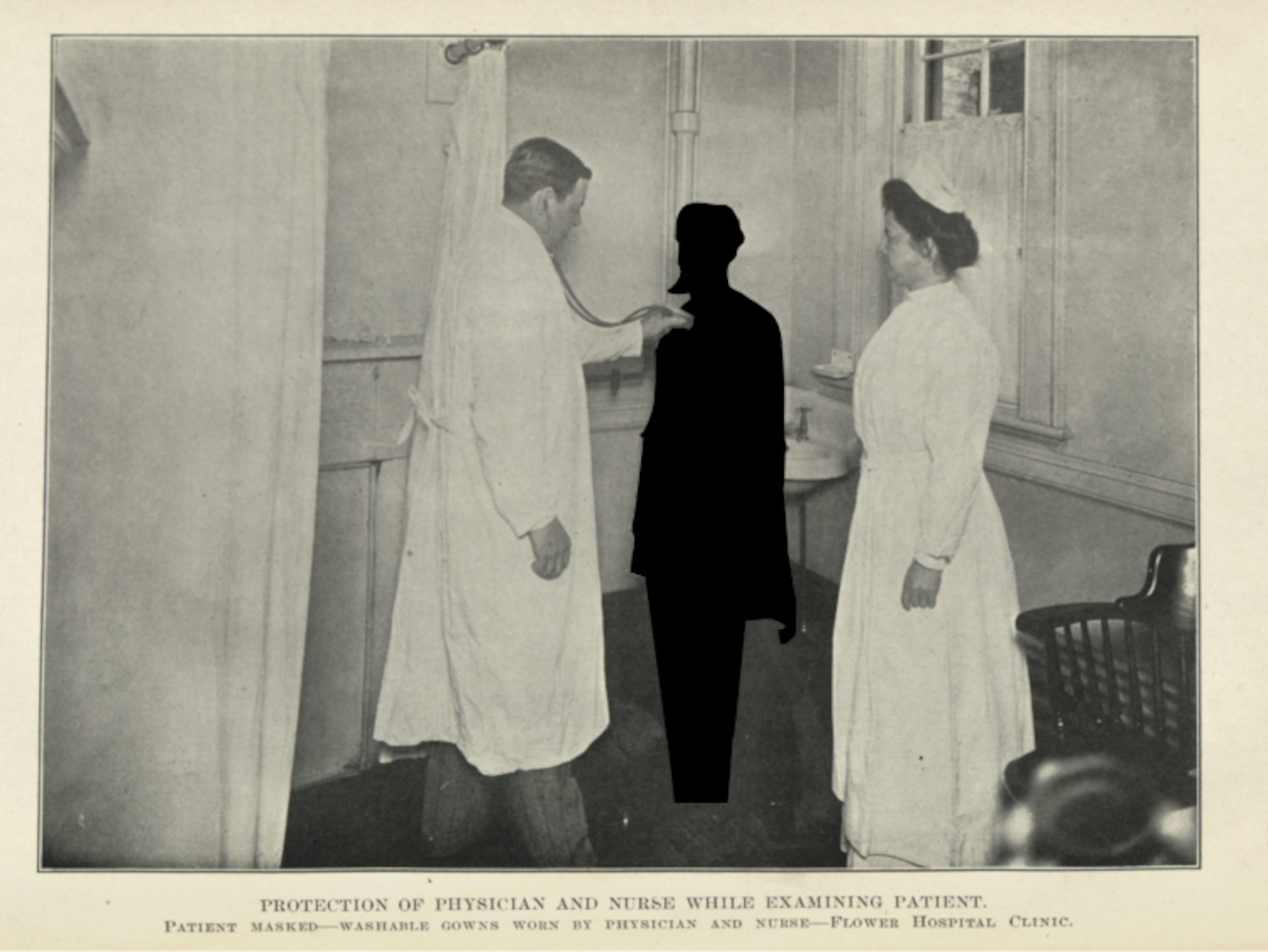

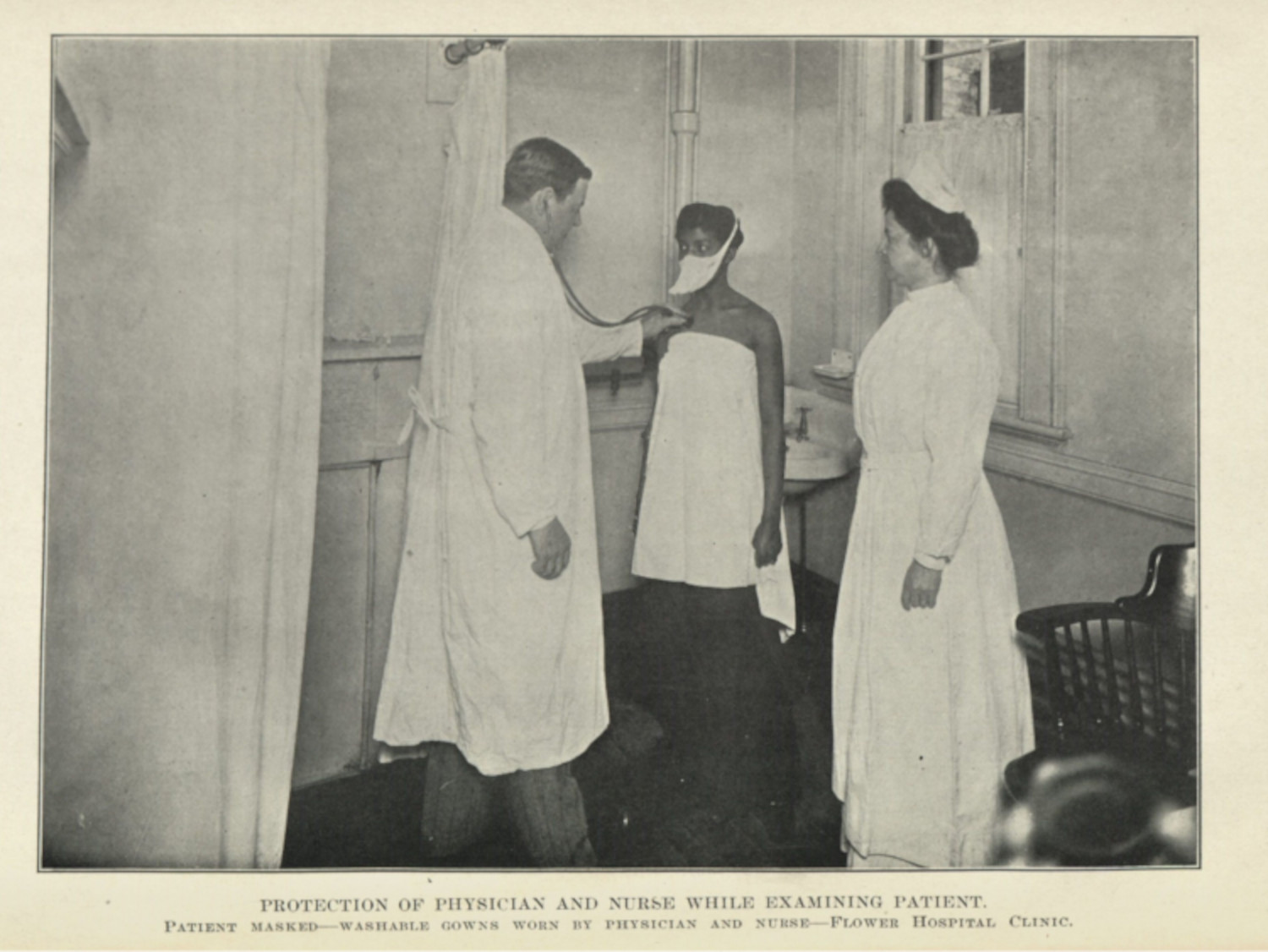

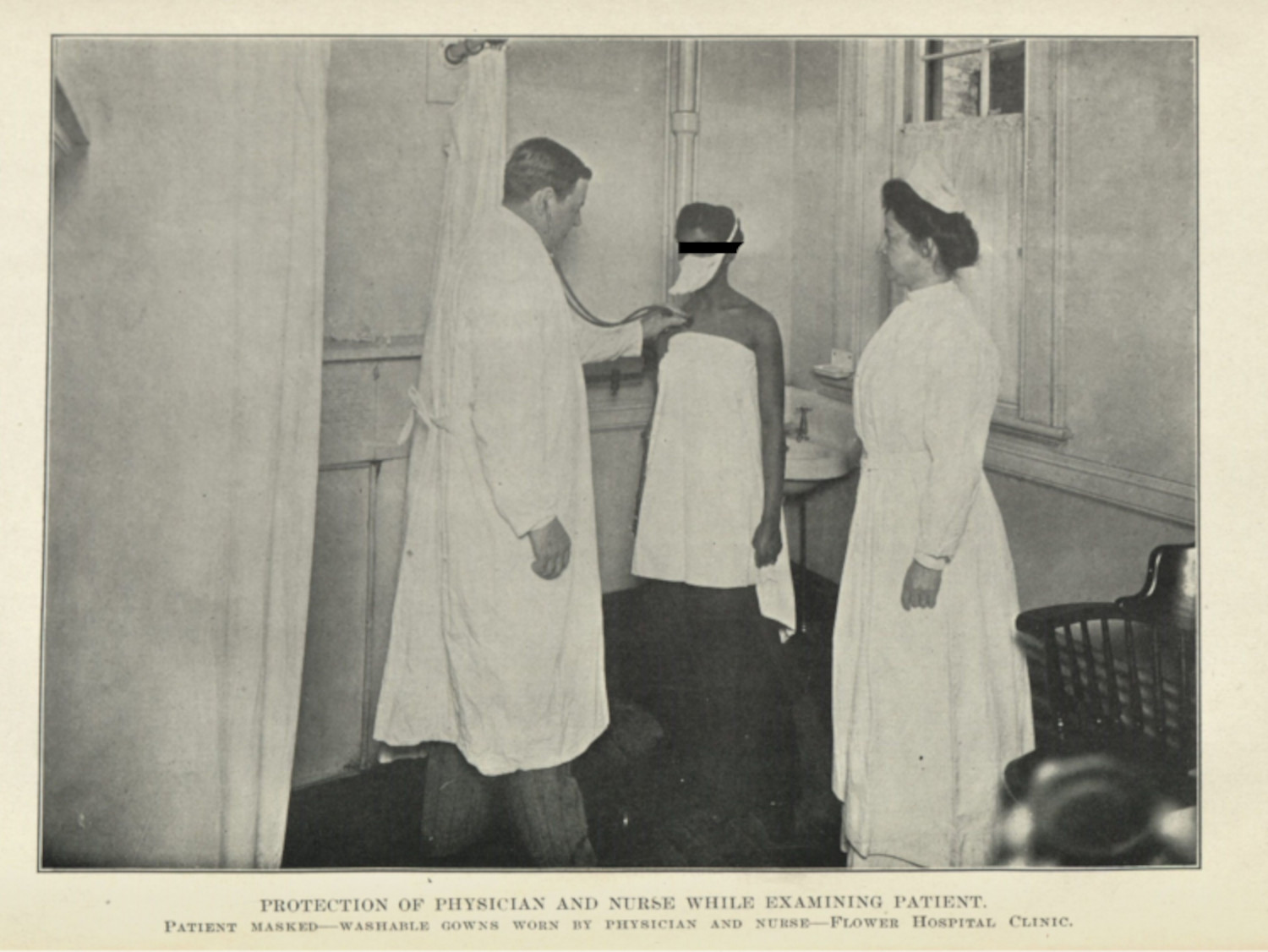

3.2.1 | 3.2.2 | 3.2.3 | 3.2.4 | 3.2.5 | 3.2.6Dermographic Opacities

3.3.1 | 3.3.2 | 3.3.3 | 3.3.4Tactical Pretensions

3.4.1 | 3.4.2 | 3.4.3Designing Opacity

A Shift towards the Anticolonial

4.1.1 | 4.1.2 | 4.1.3 | 4.1.4Refusals and Opacities

4.2.1 | 4.2.2 | 4.2.3 | 4.2.4Digital and Ethical Workflows

4.3.1 | 4.3.2 | 4.3.3 | 4.3.4 | 4.3.5Conclusion

4.4.1Coda

Prometheus Undone

5.1.1 | 5.1.2 | 5.1.3 | 5.1.4Appendix

The Tuberculosis Corpus

X.1.1 | X.1.2 | X.1.3Web Design

X.2.1 | X.2.2 | X.2.3 | X.2.4Installation Materials

X.3.1 | X.3.2 | X.3.3Index

The previous two case studies (1.2.1; 1.3.1) have looked at tuberculosis and its influence on culture at different scales, with a focus on architecture and hygiene. What is absent from both of these case studies is the figure of medical professionals—especially white male doctors—even in contexts where the inclusions of these doctors and nurses in the frame might be beneficial.

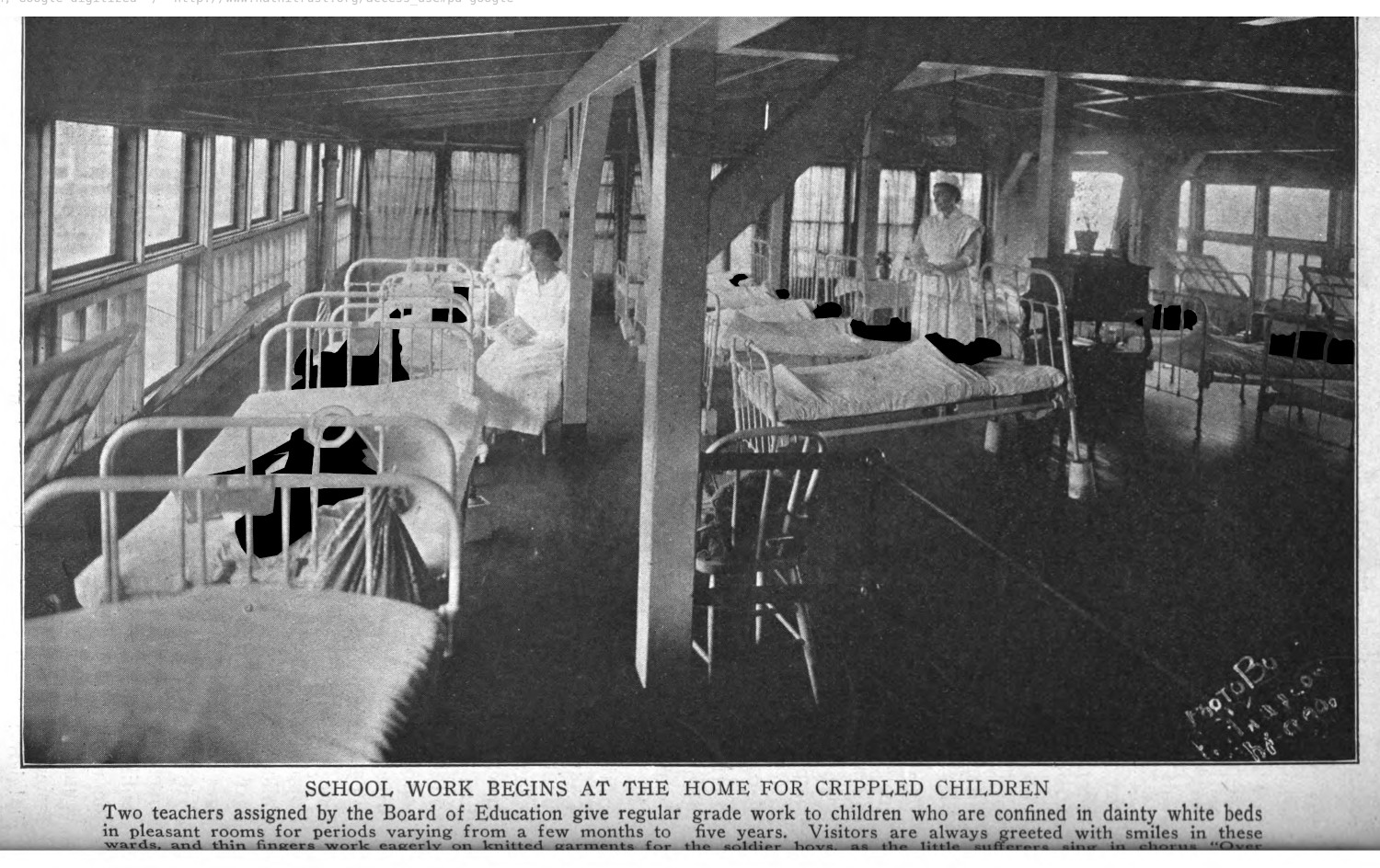

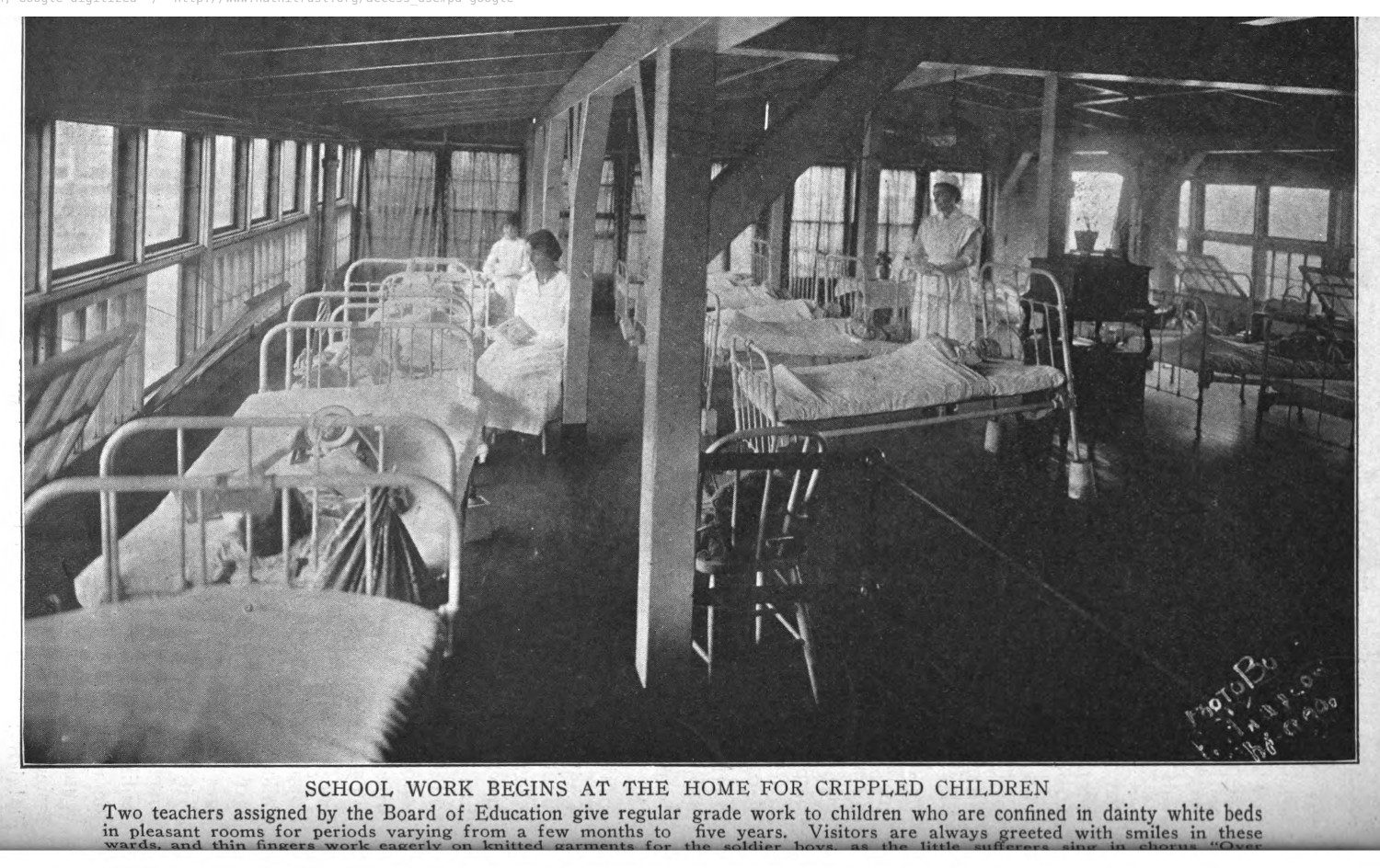

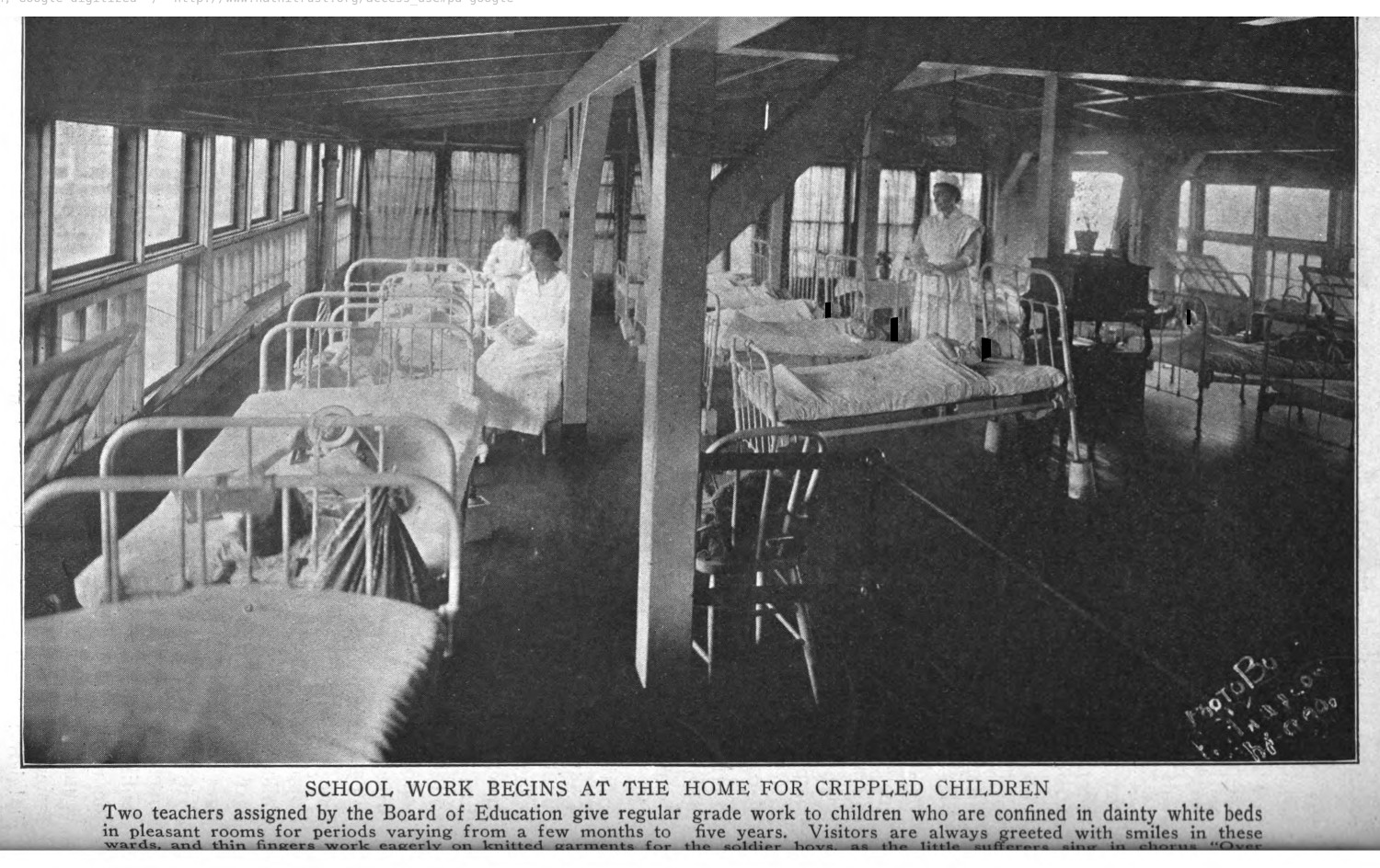

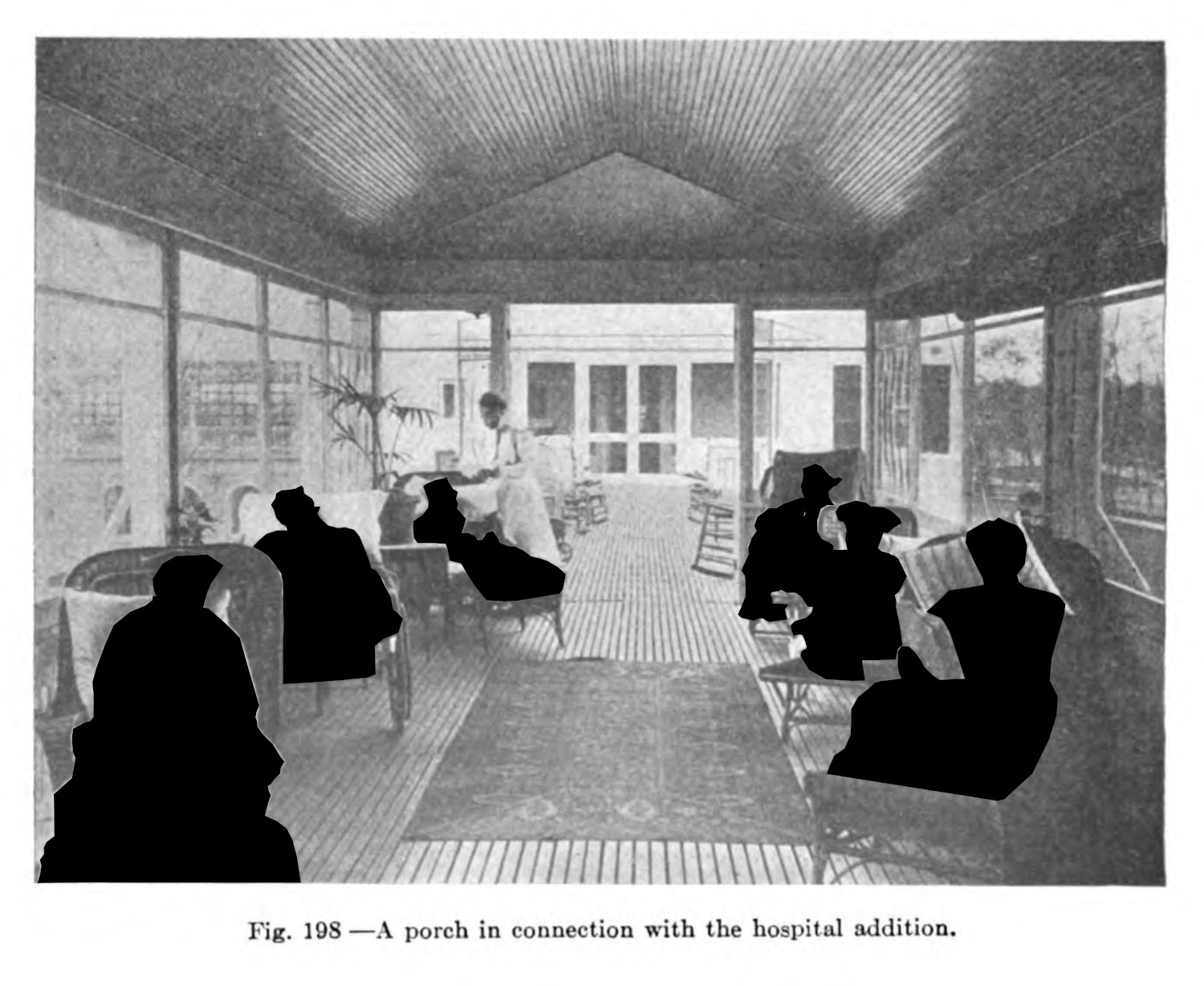

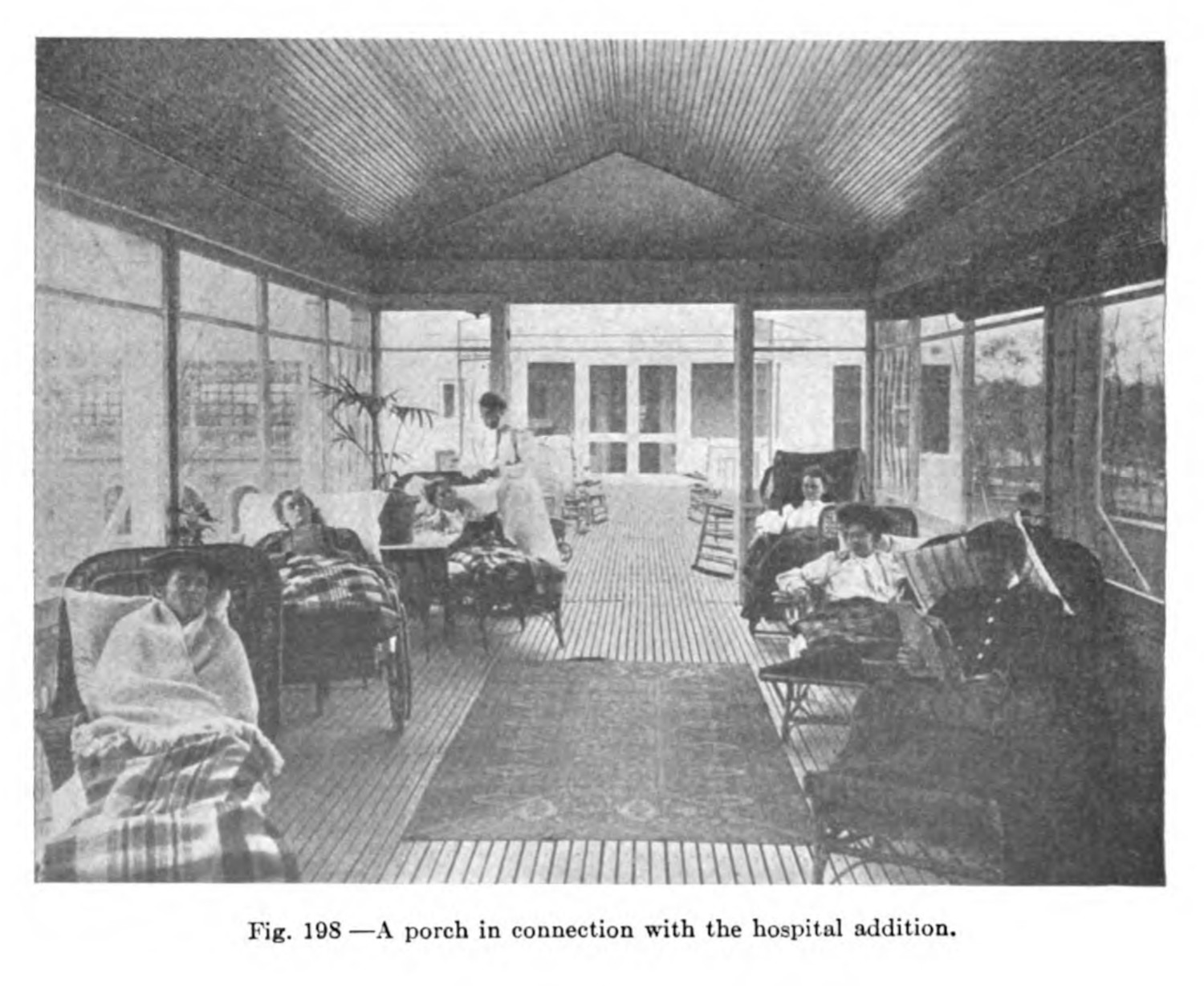

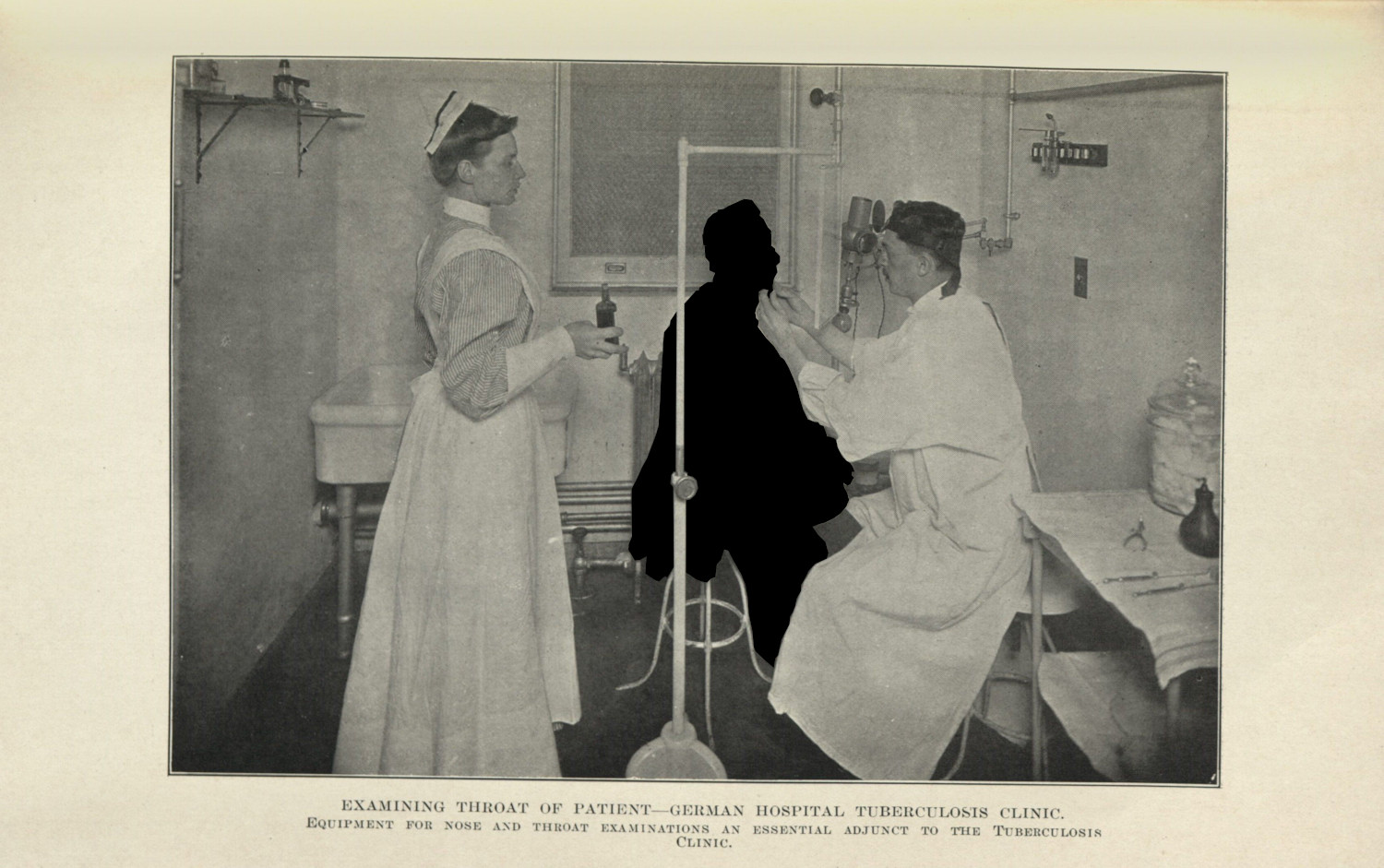

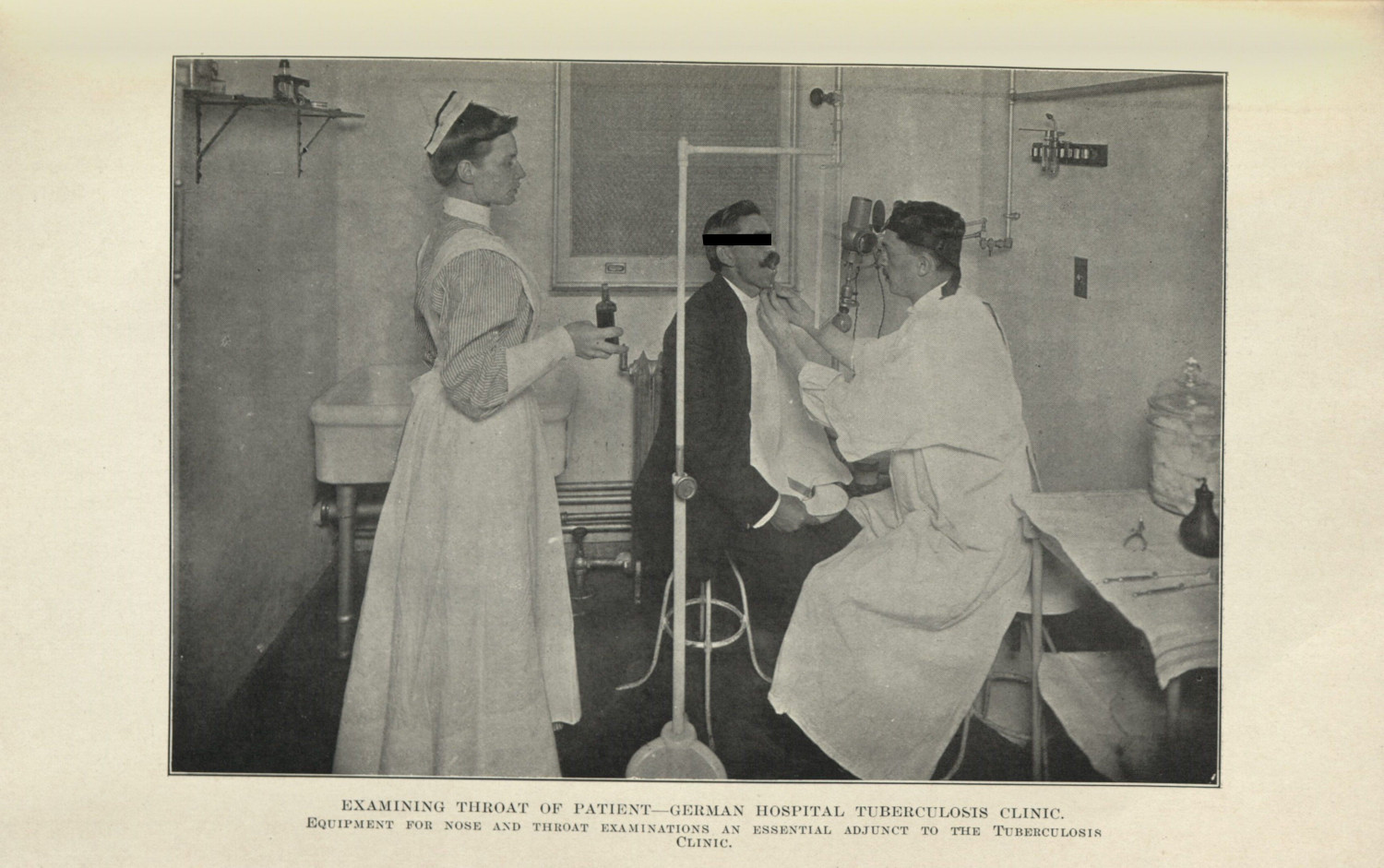

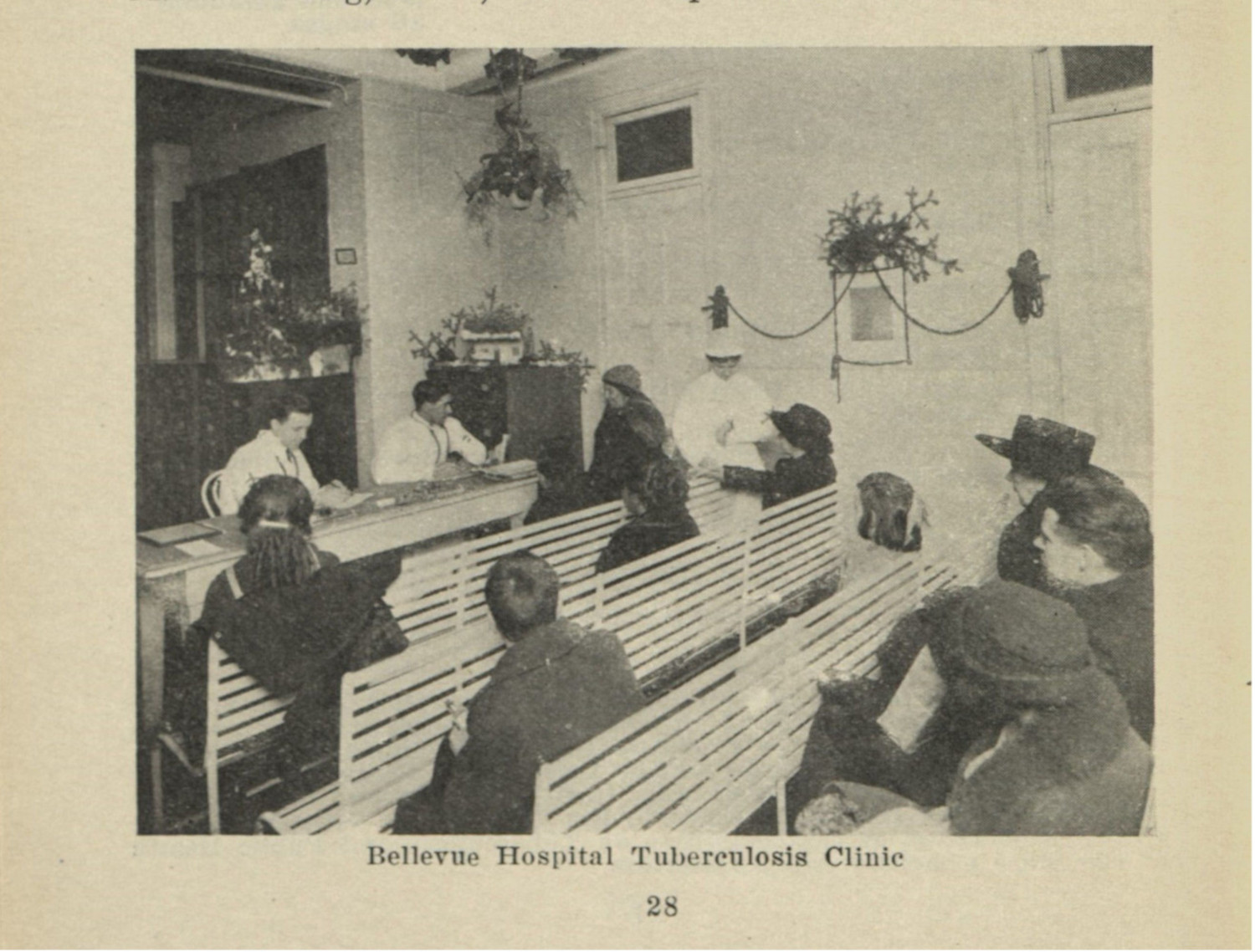

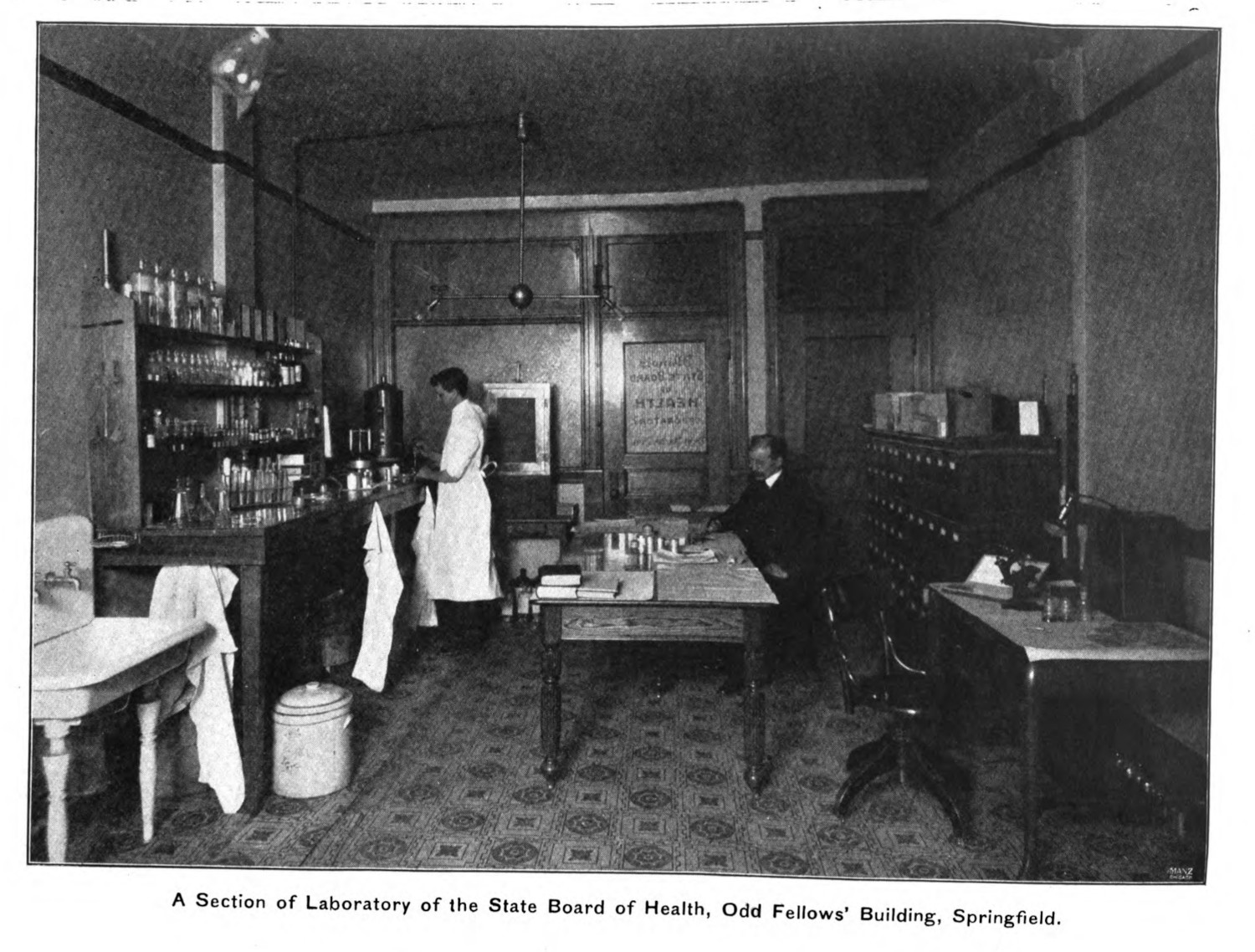

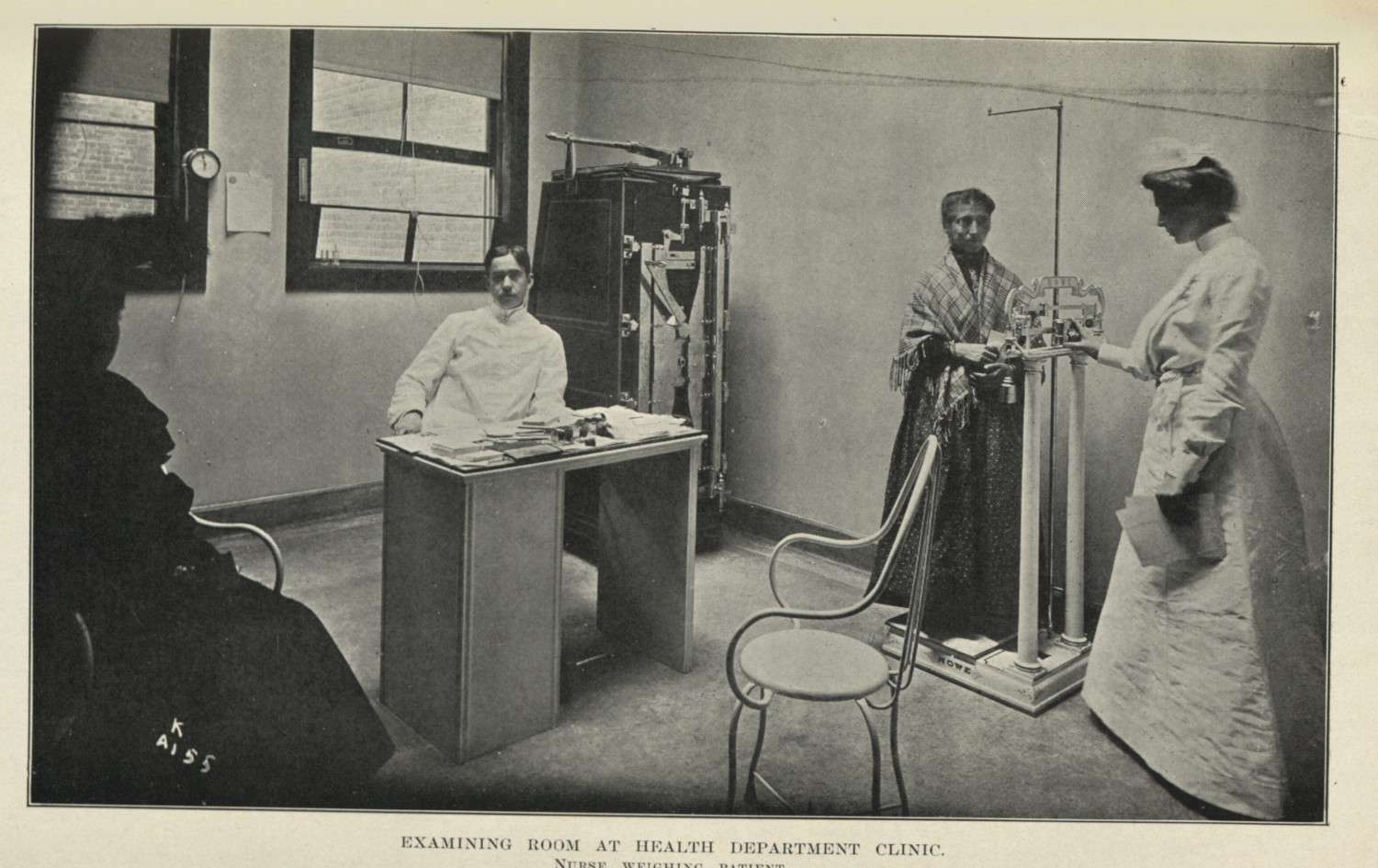

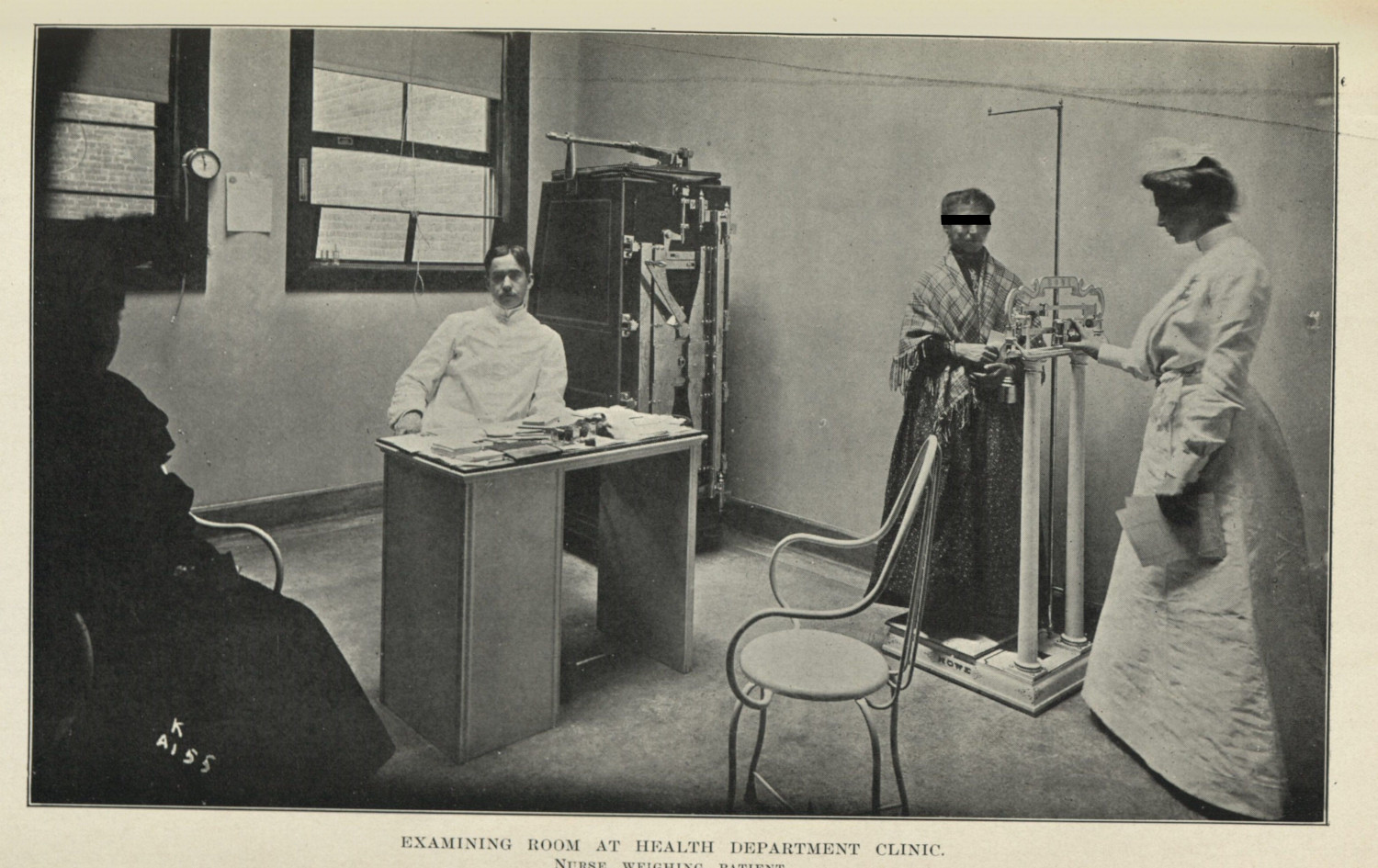

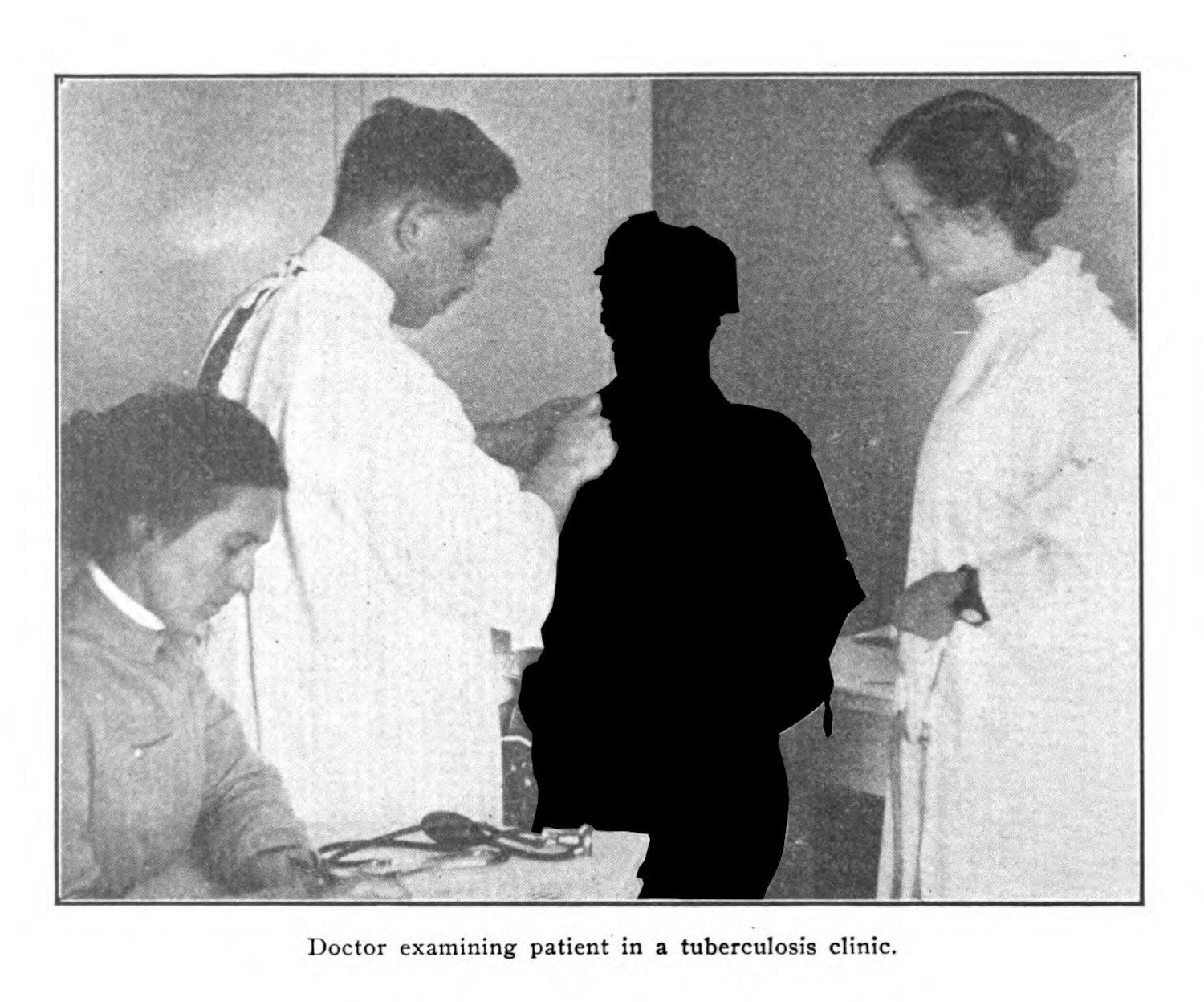

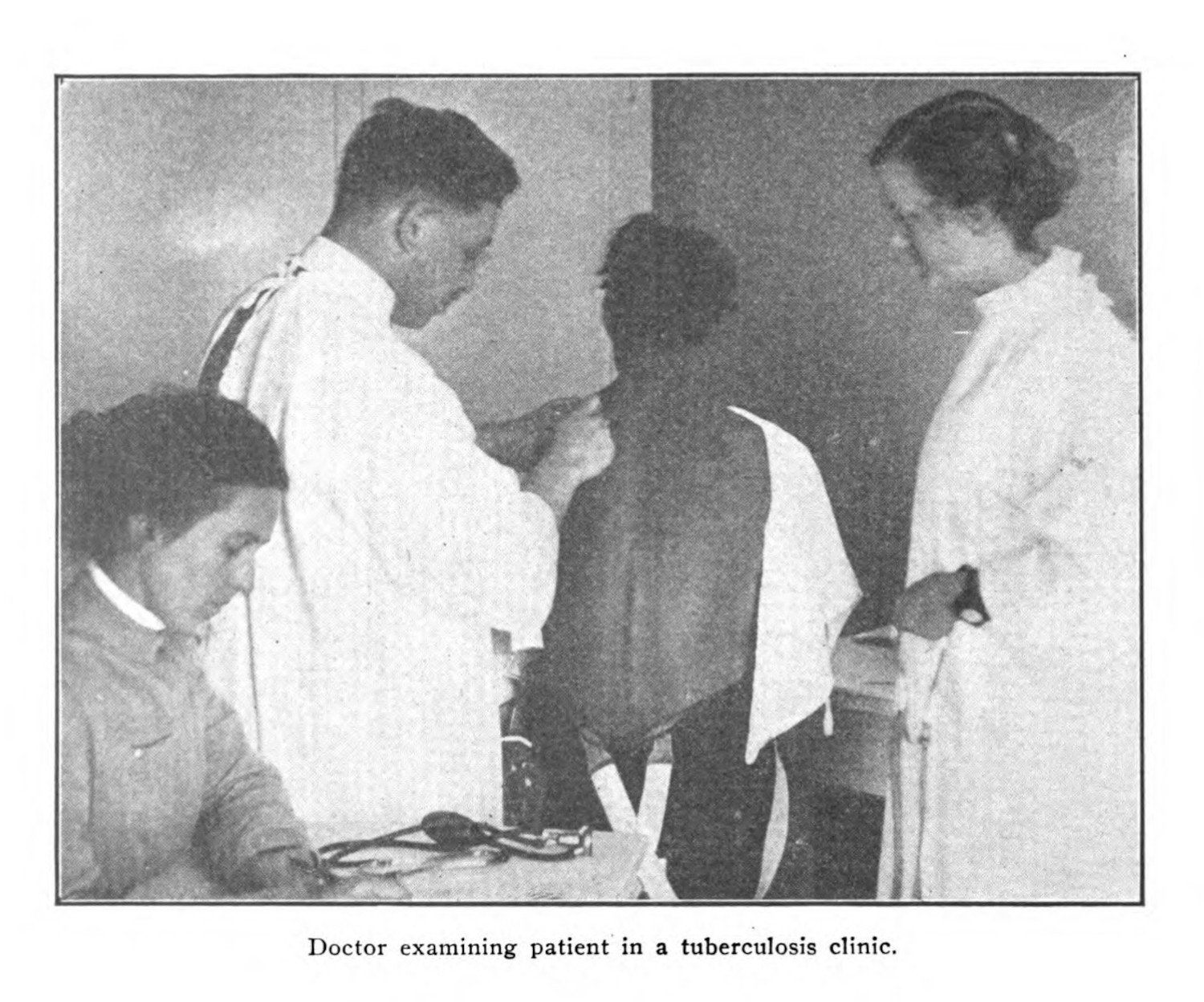

One of the important aspects when it comes to clinical vision is its unidirectional nature: doctors look at their patients, defining symptoms and pathologies, but the gaze is never returned.1 There is power in being behind the camera, being the person who illustrates a body or organ, being the radiologist and not the one whose body is photographed, illustrated, or x-rayed. Medical professionals seem adept, consciously or otherwise, at not being captured in the visual rhetoric of their arguments. Their gaze looks outward, and even when medical personnel are in line of sight of the camera, usually it is nurses whose bodies and faces are displayed in these images (figs. 1 & 2). The power of absence—to see and not be seen—positions doctors especially as impervious to the criticism levied at their patients.2

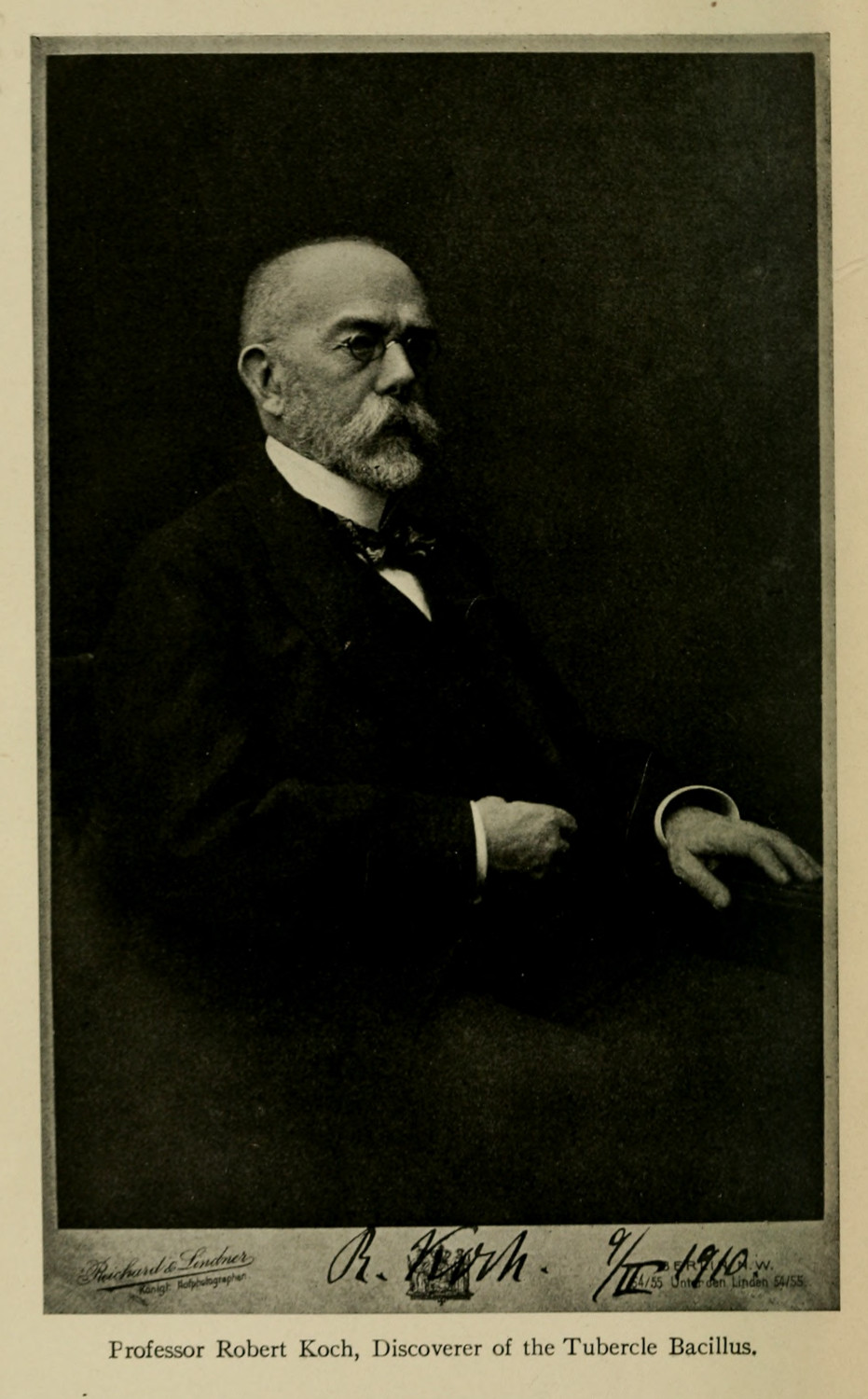

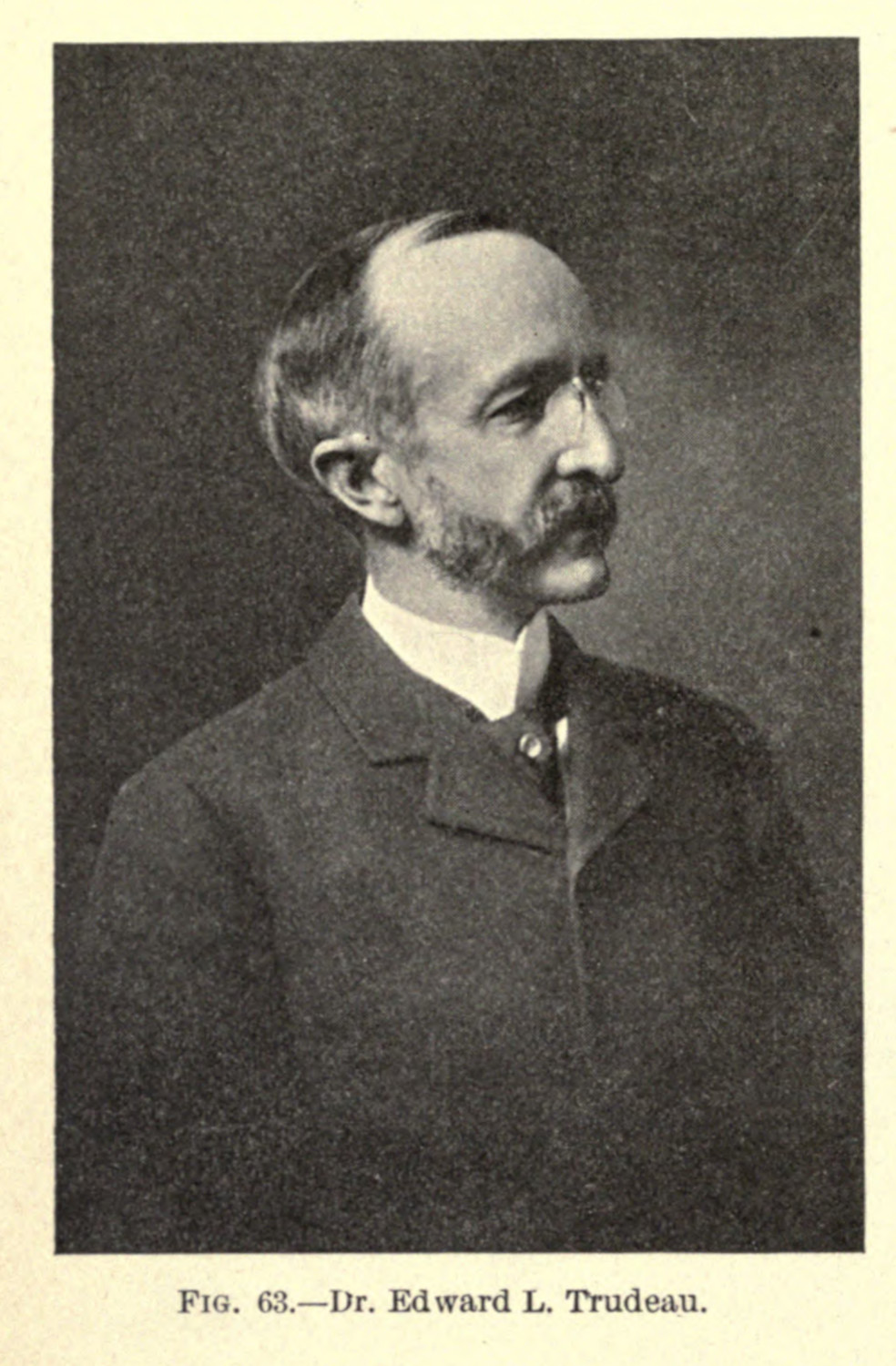

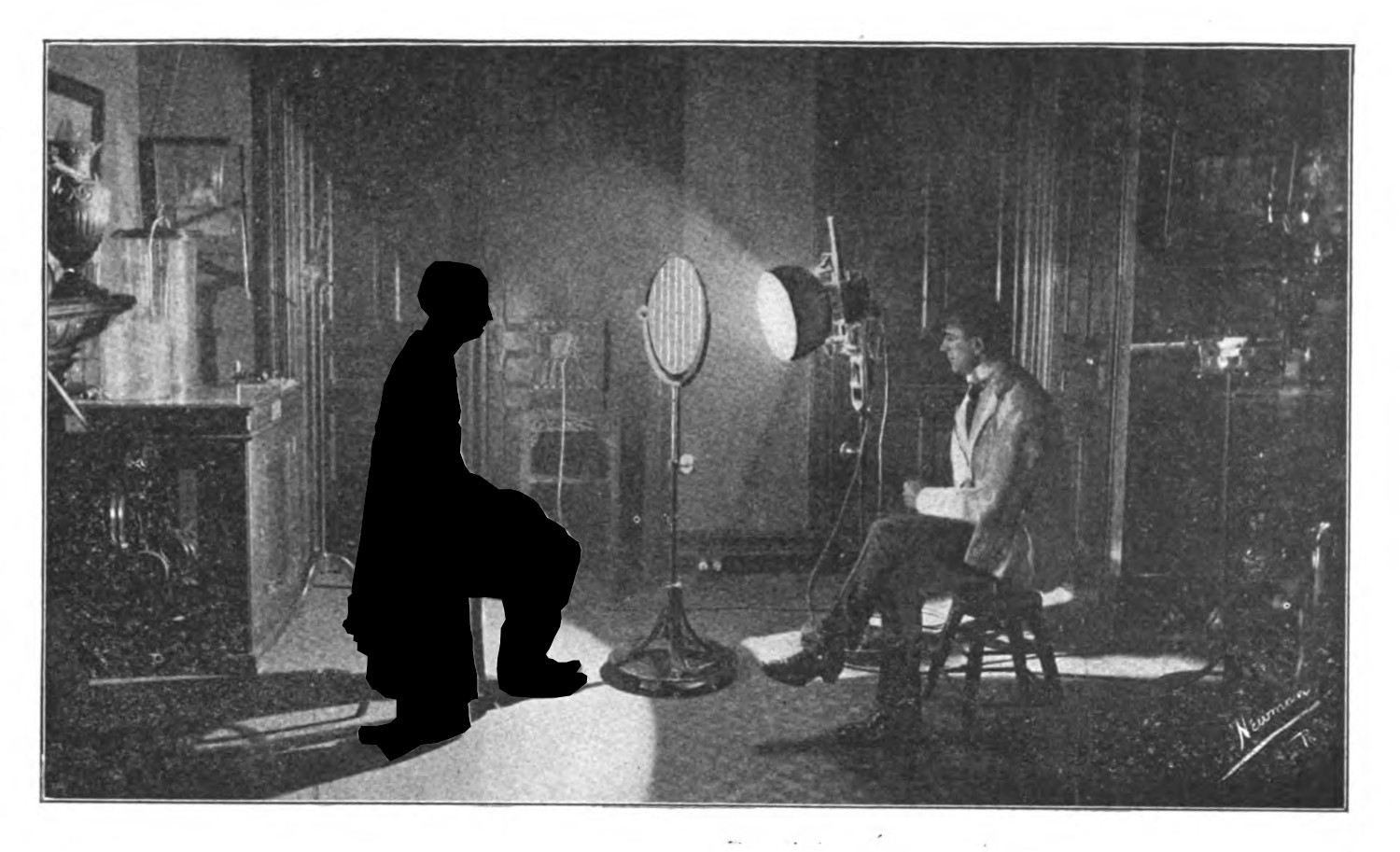

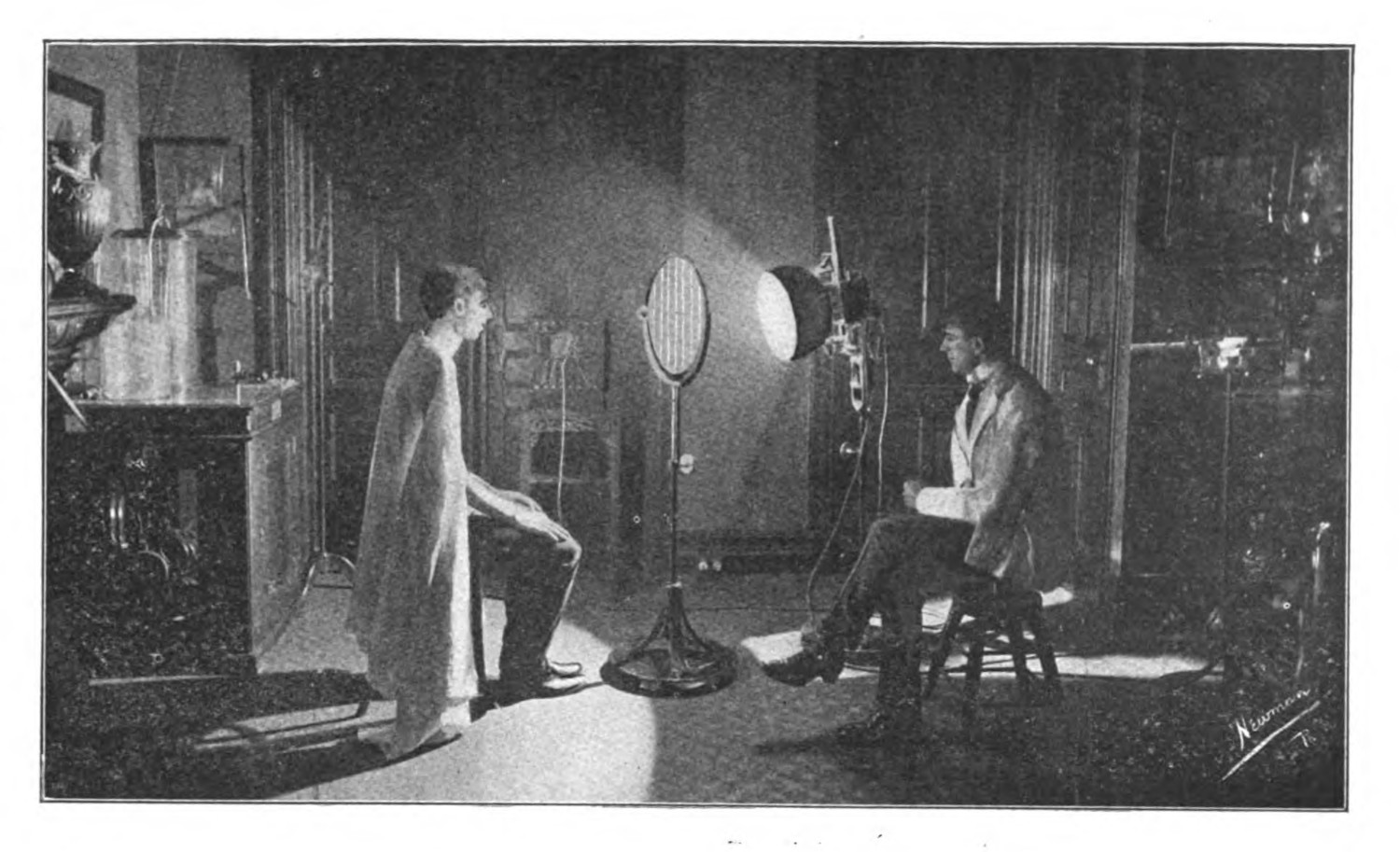

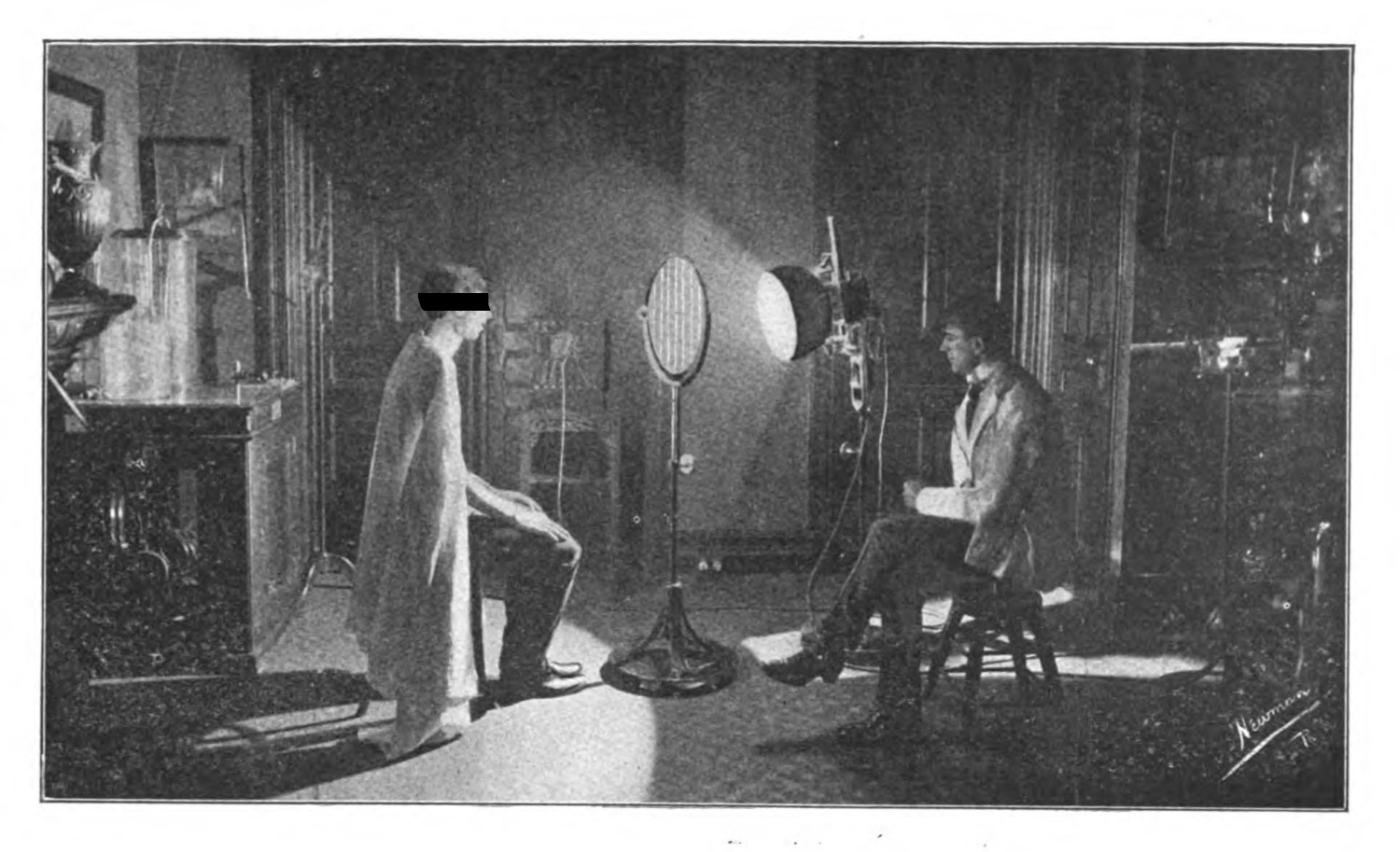

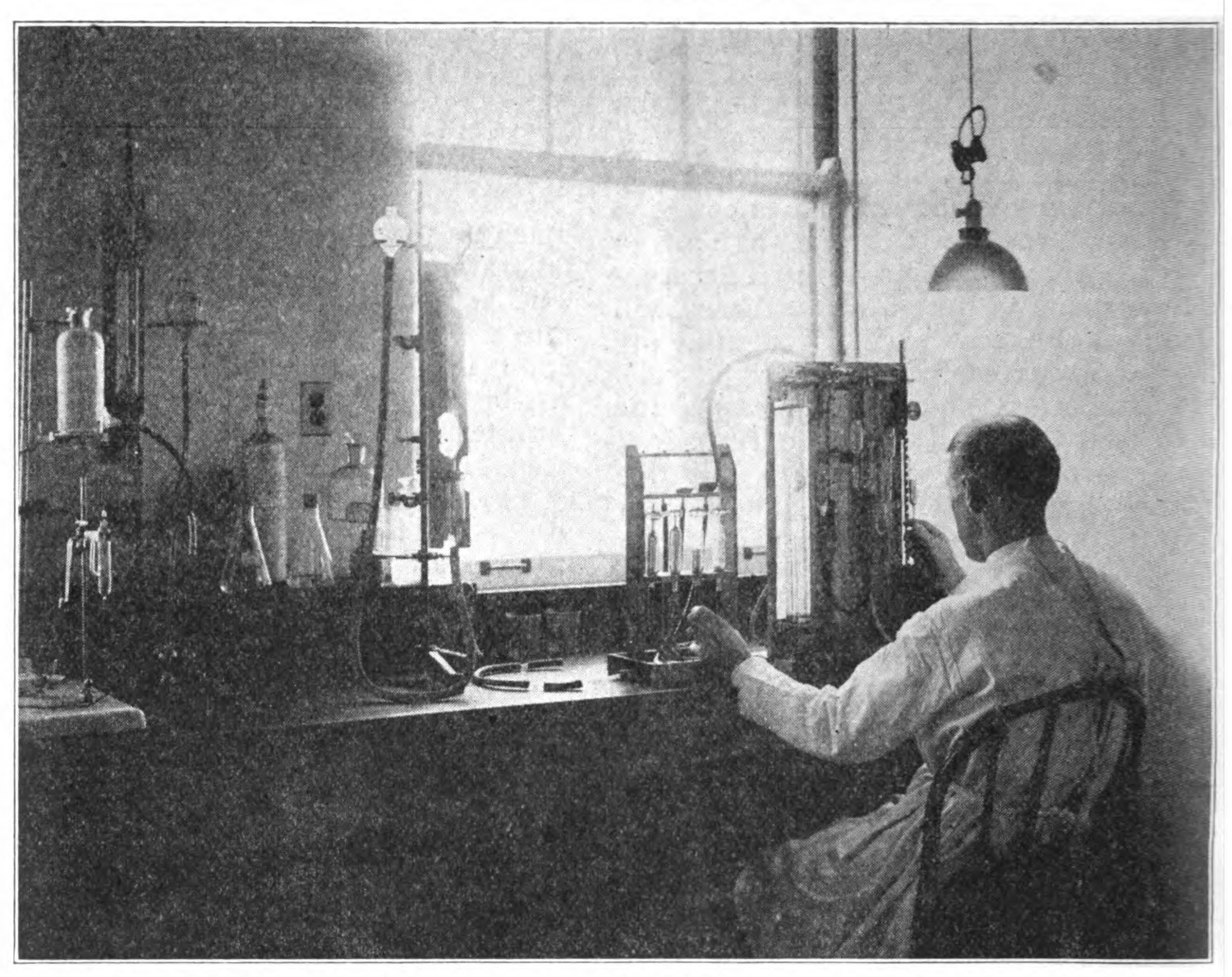

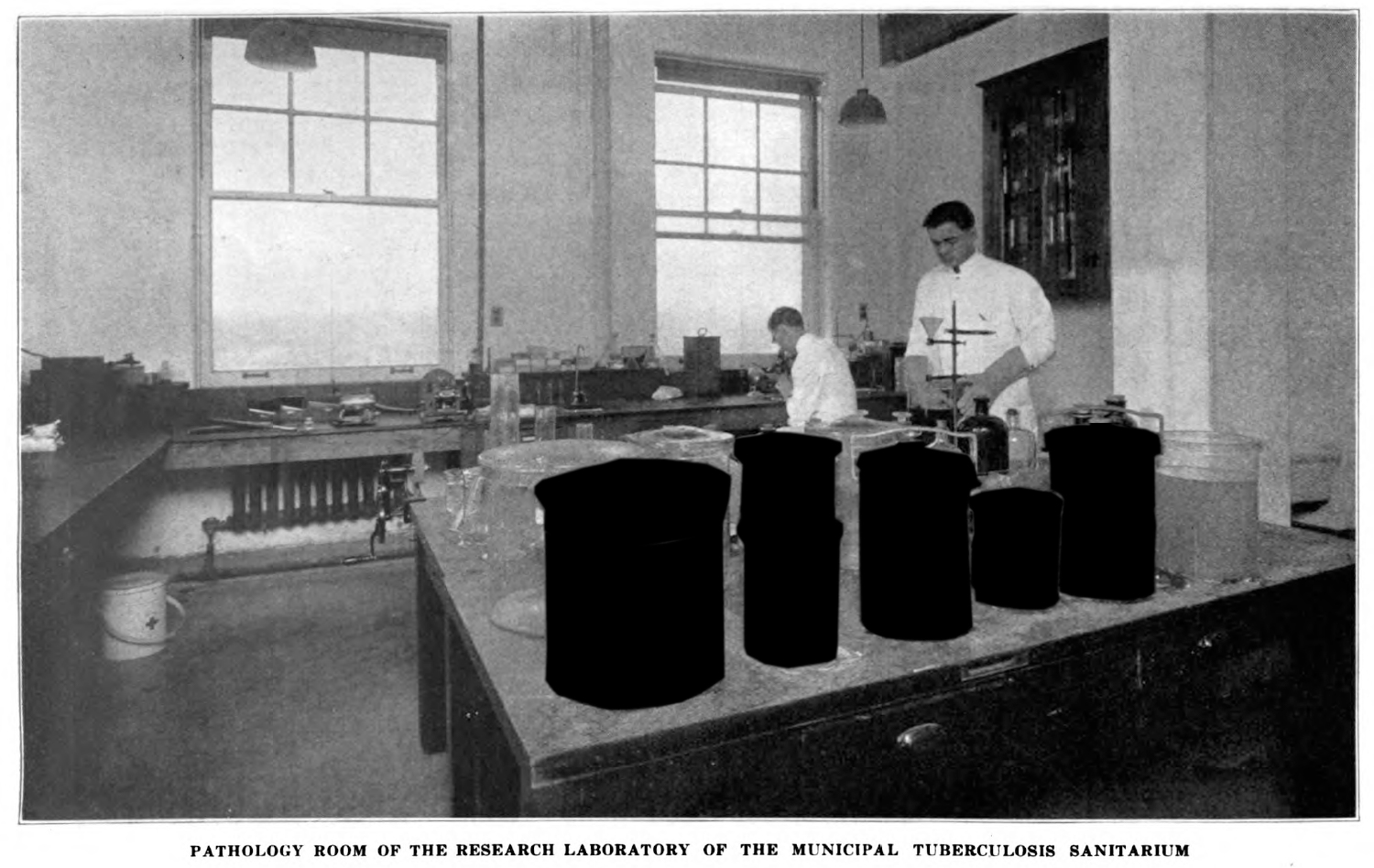

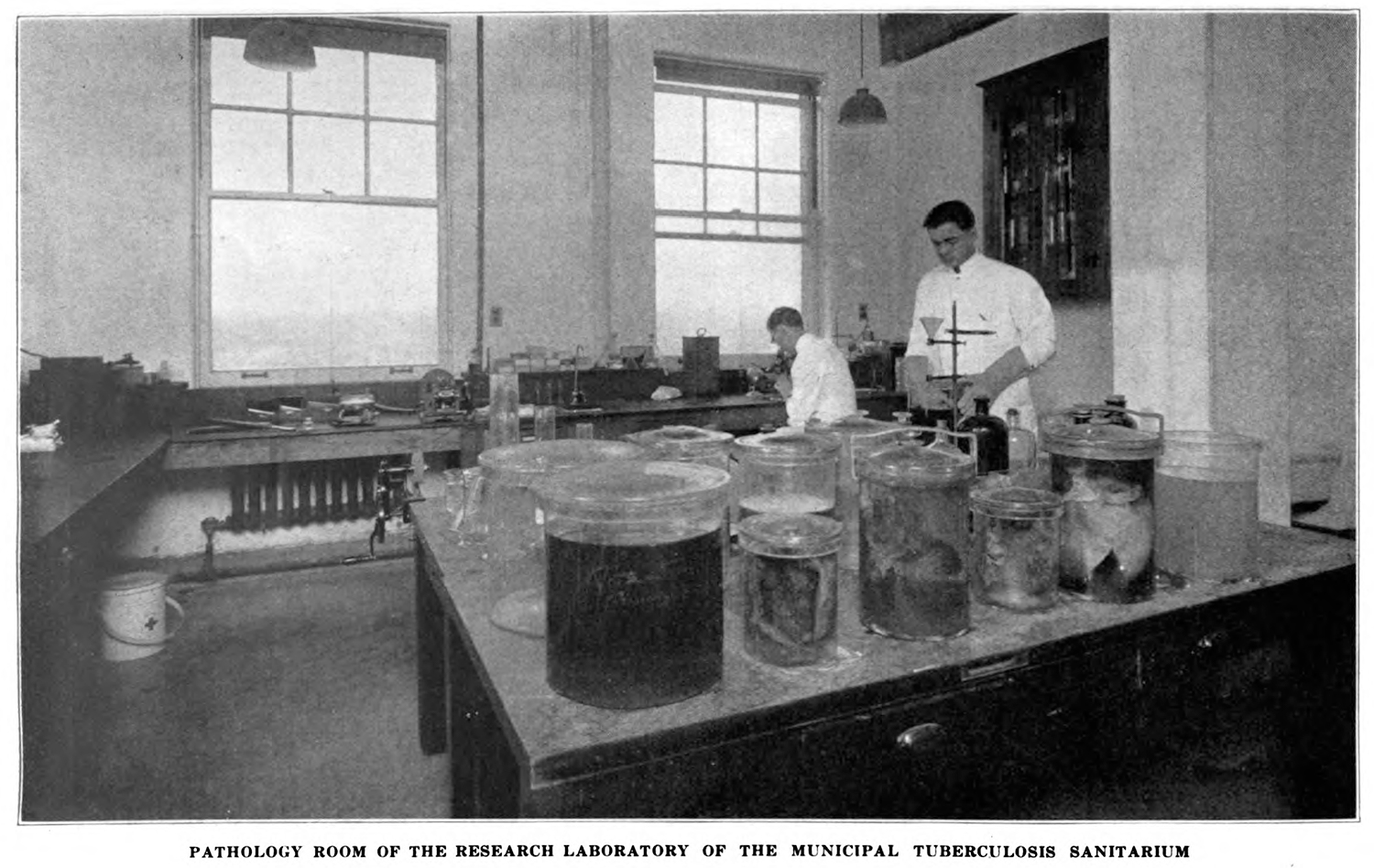

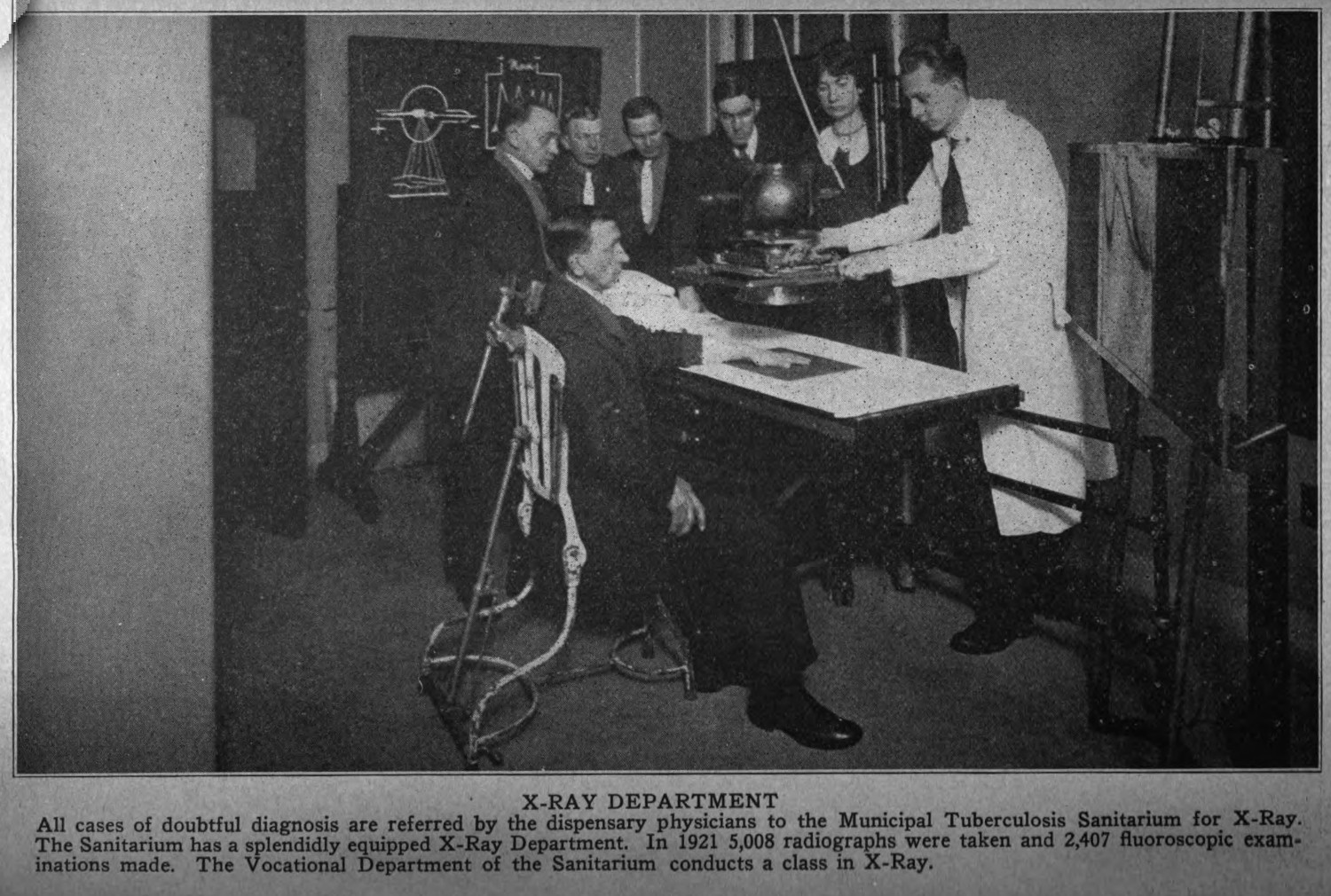

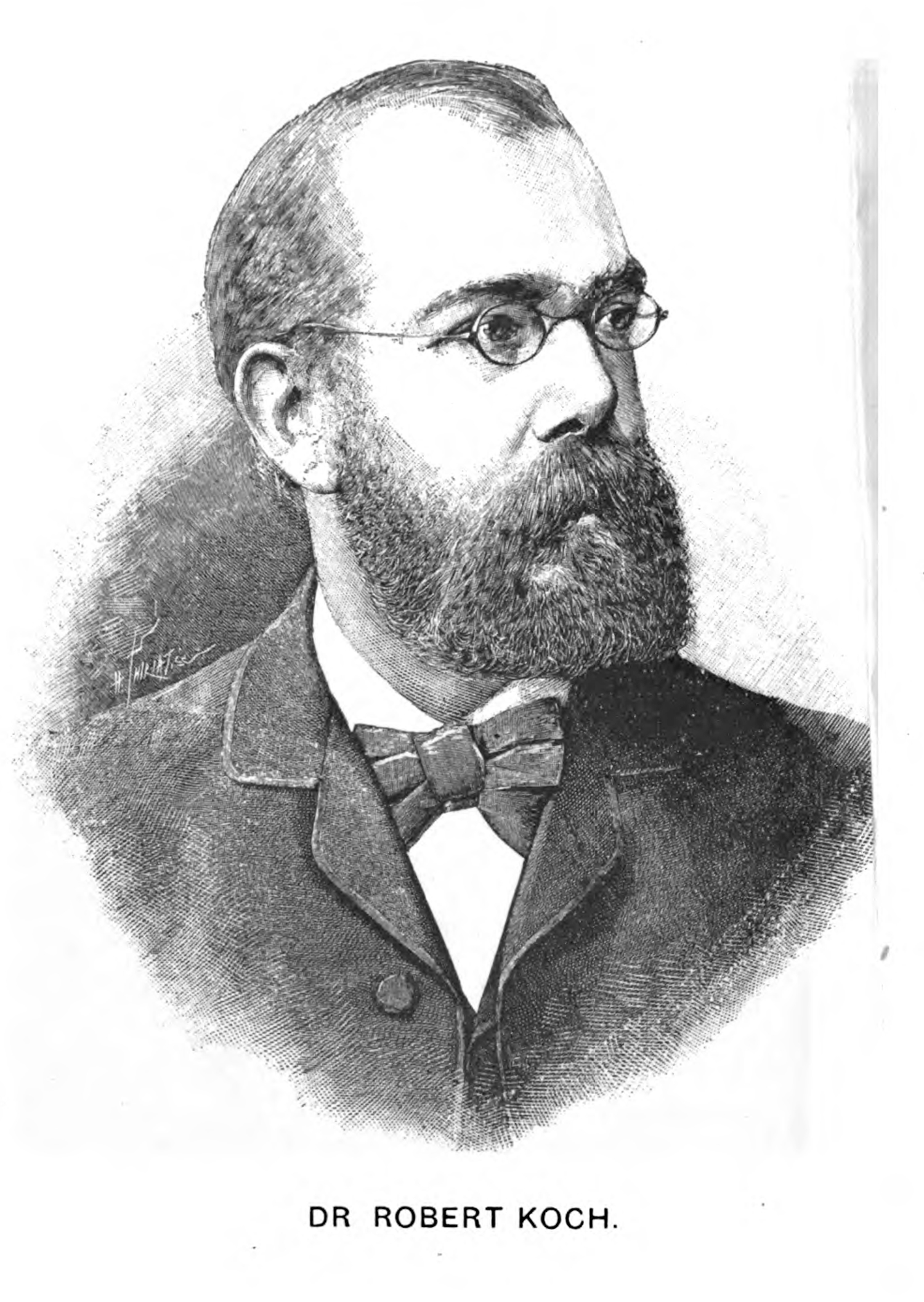

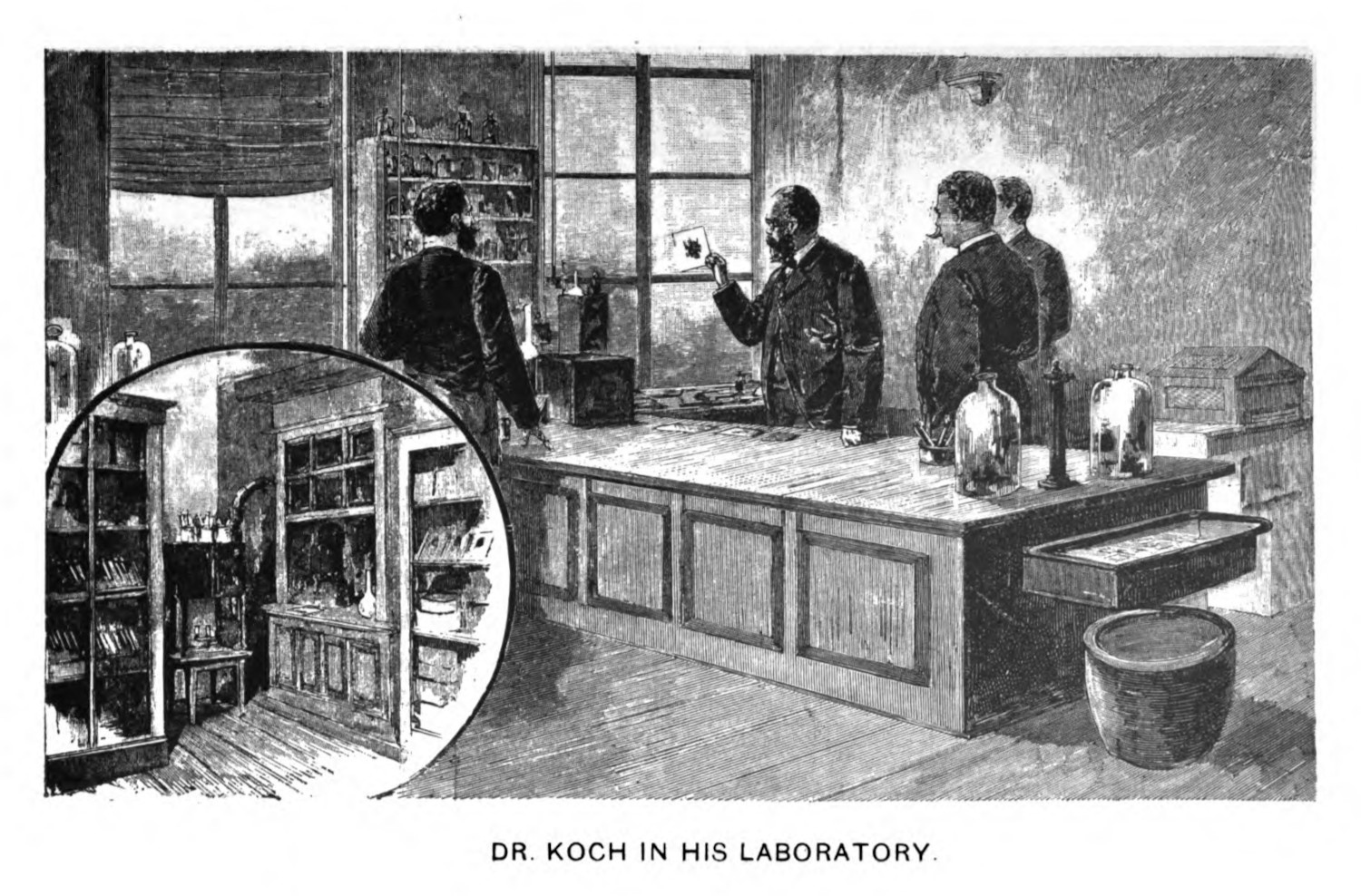

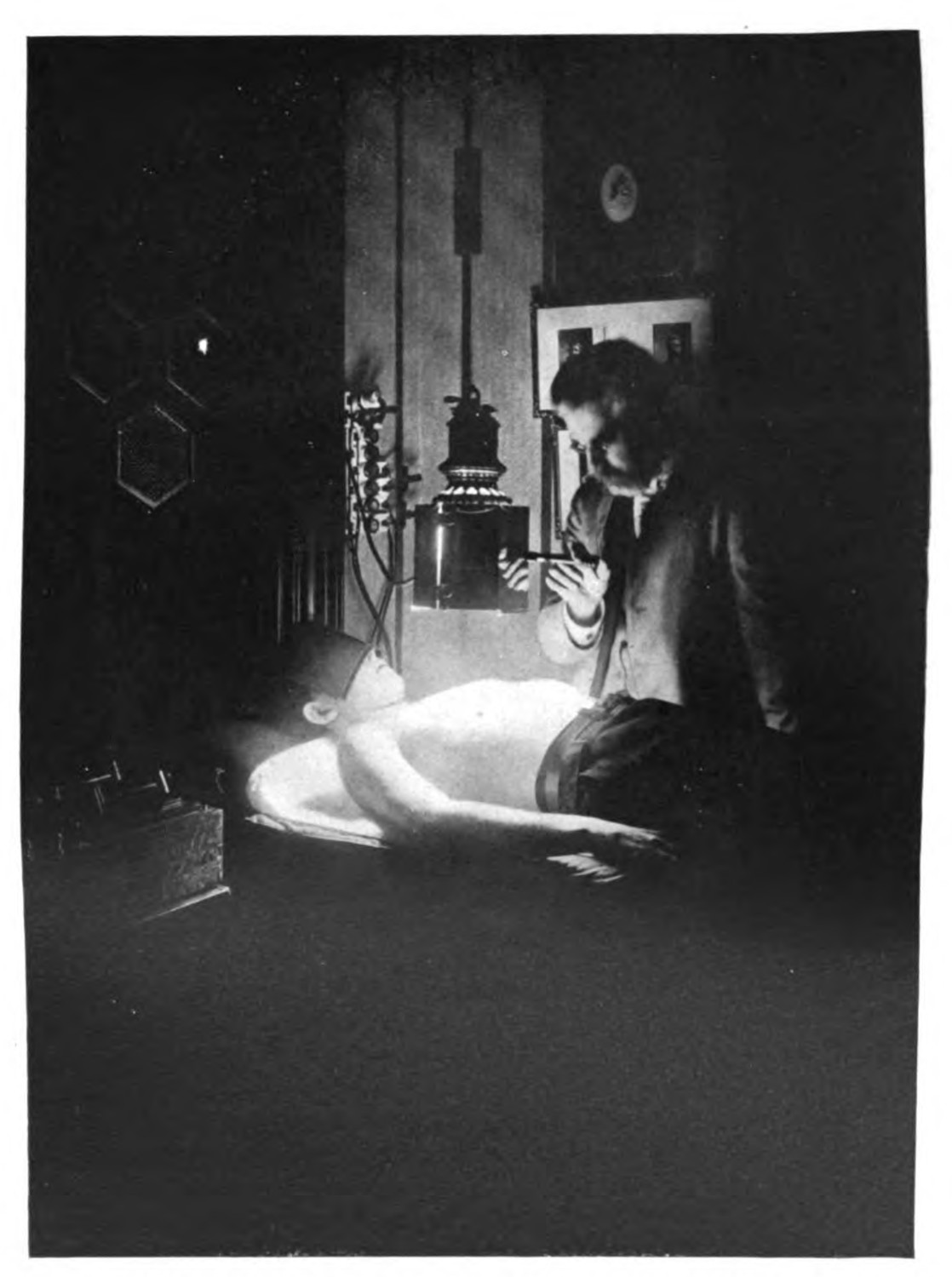

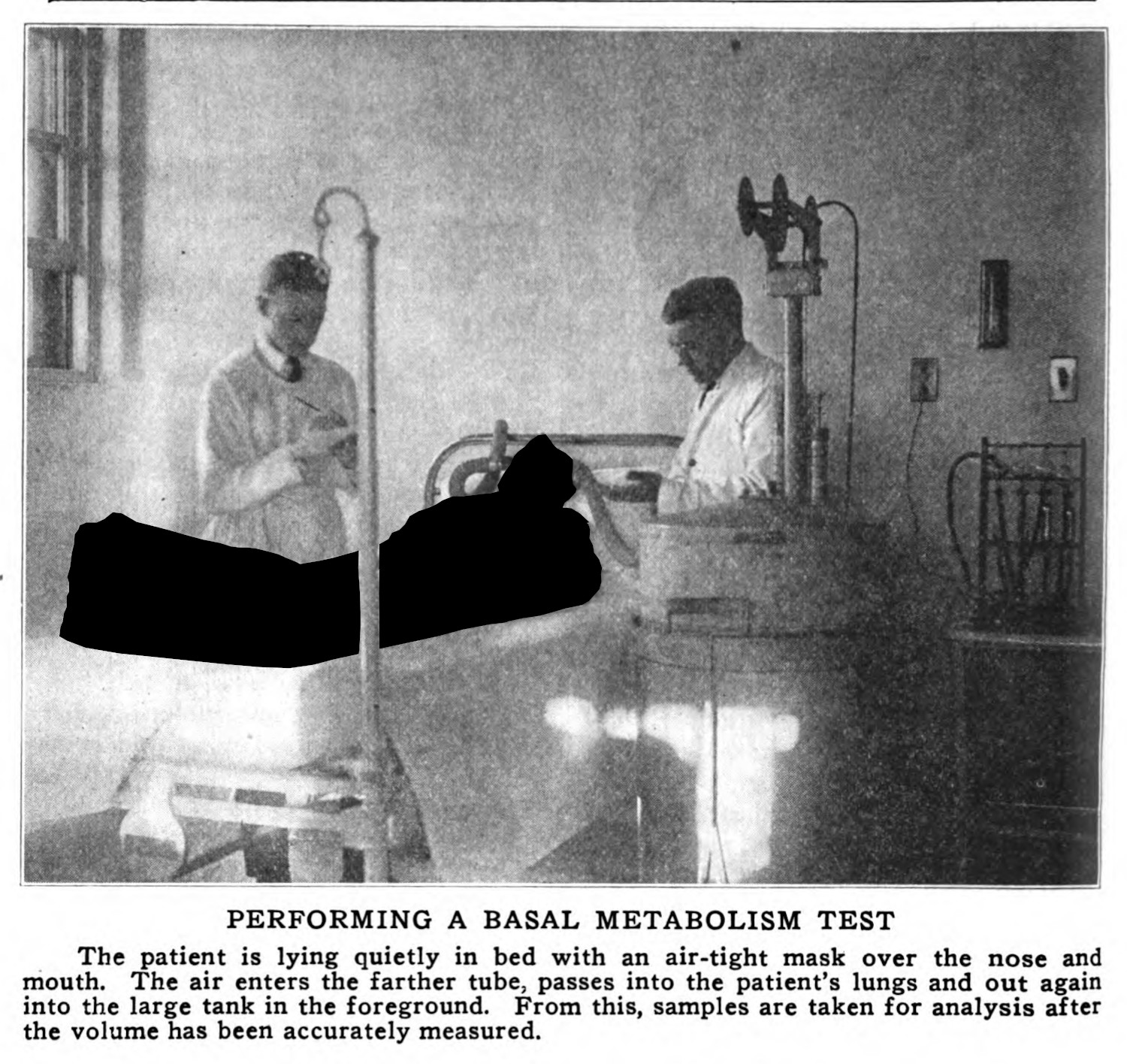

It is hard to find doctors in the tuberculosis corpus and image dataset (X.1.1; X.1.3). They appear in two prominent contexts: the first is in the professional headshot. When these images are used in an argument, and not in the frontmatter of a book or as part of an obituary, those moments are often reserved for the most prominent and influential scientists, with Robert Koch (figs. 3 & 13) and E. L. Trudeau (fig. 4) being the most common figures. The other context in which doctors appear is in more candid shots, where they are shown treating patients or doing laboratory work. These photographs are not as common as many of the other images, and these depictions tend to appear in promotional contexts or in publications that describe daily operations of a hospital or sanatorium. There is also a notable difference in their mise en scene, with doctors treating patients in more sparse exam rooms or hospital rooms (figs. 5 - 7), or with doctors being caught in semi-candid or posed stances in laboratory rooms or pharmacy/dispensary rooms (figs. 8 & 9).

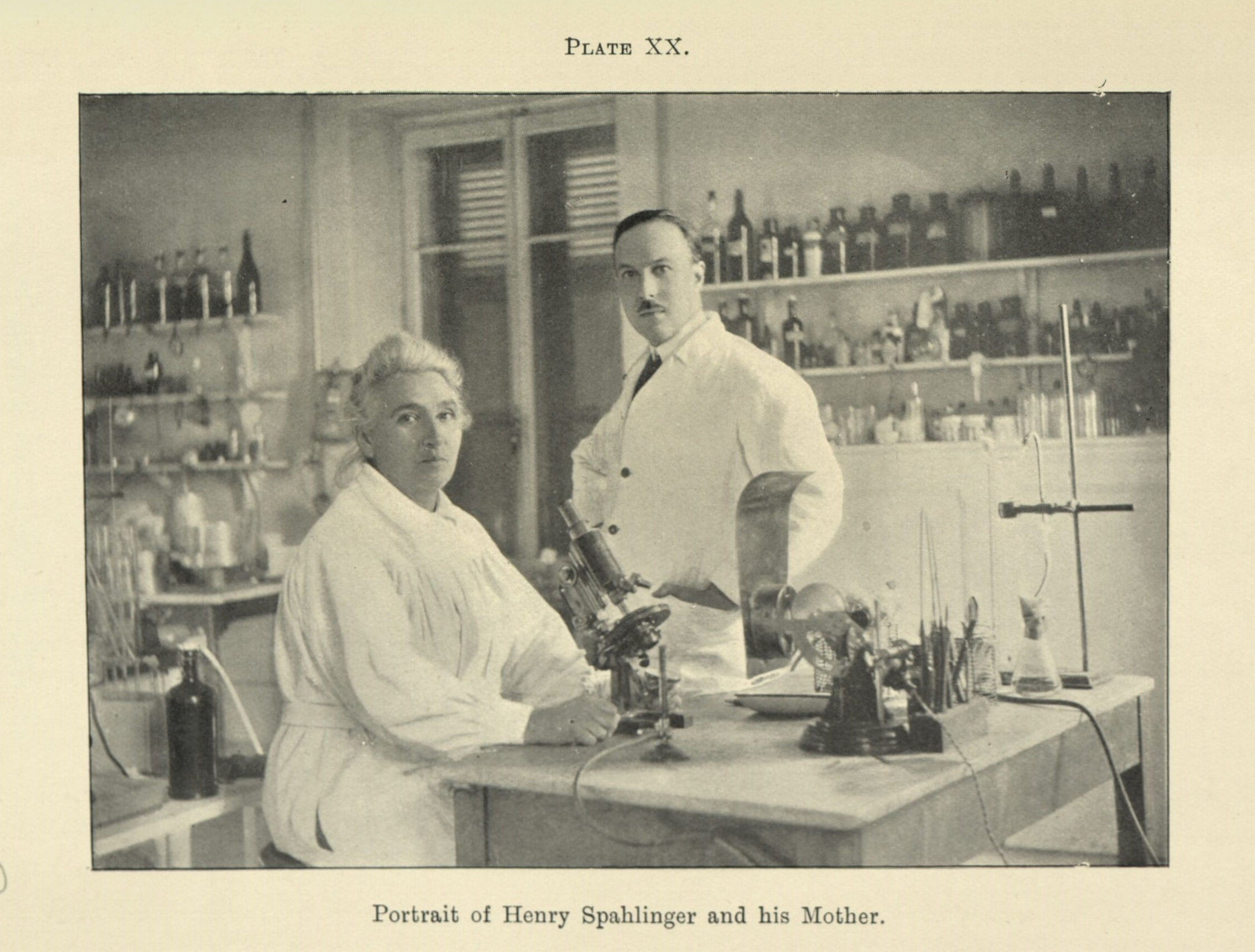

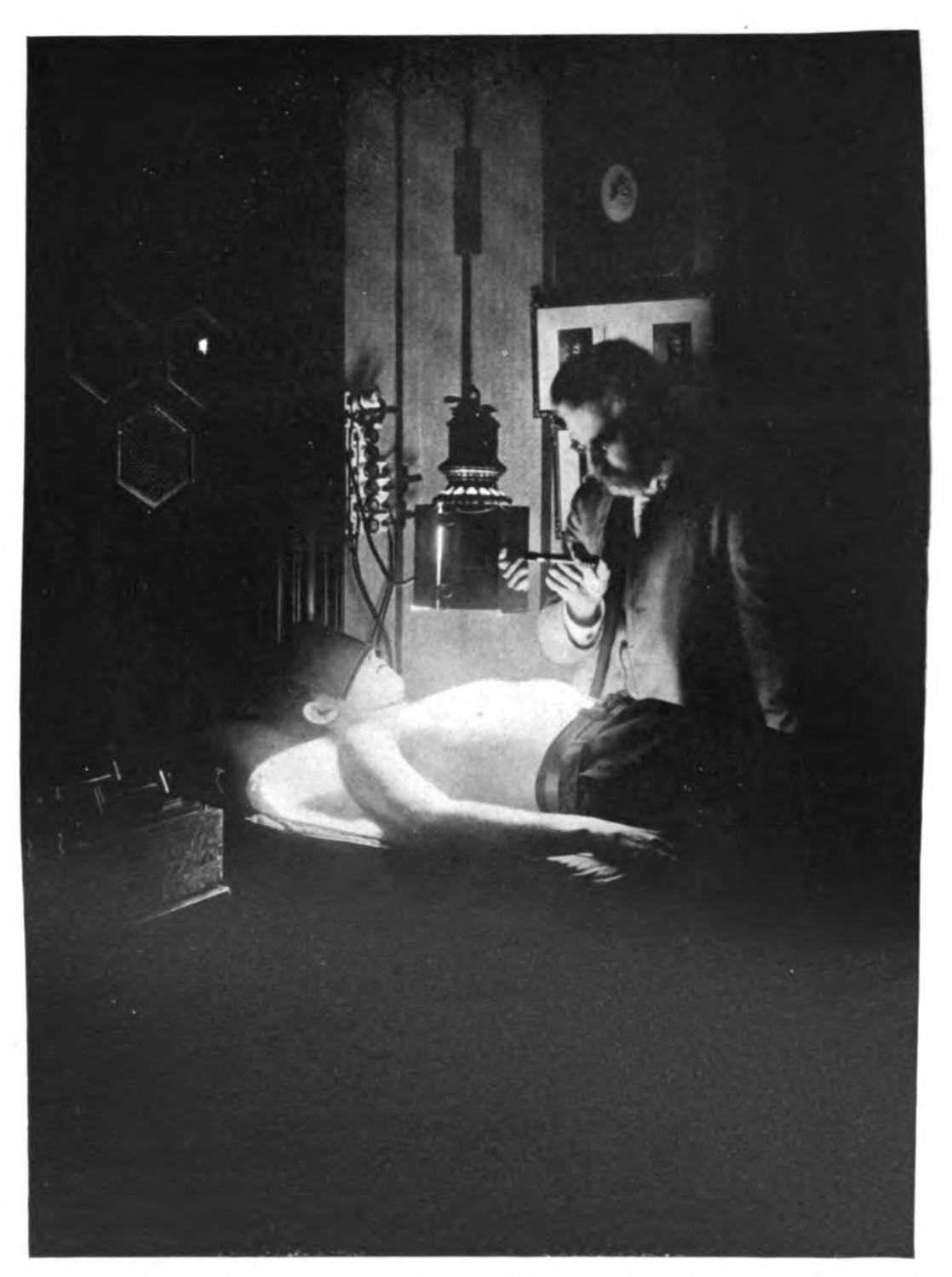

The professional image of medical scientists is instead bound to these clinical spaces, with the accoutrements of the most advanced, scientific practices surrounding them. Often doctors are posed around their equipment (fig. 10 & 12); other times, there are human remains in frame (fig. 11). These images are coded with the technical iconography of modern science—pharmaceuticals, microscopes.3 Often the doctor is framed in a candid, unassuming way, often doing some kind of beneficial work—caring for children, attending to a patient, doing surgery. The context here is important, because the images seem more associated with facilities and the institution and not people, not even the doctors themselves.

A model of this practice can be seen in the ways Robert Koch was framed in the tuberculosis discourse. The German bacteriologist had been the subject of a prominent profile in Harper’s Weekly,4 and the images made for that profile were commonly reproduced: both his portrait (fig. 13) and the drawing of the scientist in his lab appeared multiple times in my research (fig 14). Koch’s framing includes a detail to another space in the lab, presumably cabinets with equipment, that are associated with his authority as a man of science. In all of these images the figure of the doctor is dwarfed by the tools of the medical trade, or by a clean, exquisitely furnished laboratory space. These images convey what was a cutting-edge approach to tuberculosis, something which sanatoria would use in their promotional materials (1.2.2). It also conveys a kind of labor that is separate from but intrinsic to the act of curing; these spaces, so advanced in their processes, were also distinctly separate from the patient’s bodies.

The images of patients seem almost staged (figs. 6, 8, & 10). I address this to think about how the careful framing, and the detail in exposure, would imply a kind of consent, at least from the doctor. Inviting a photographer into the space, having them set up their equipment, and posing for the image all require a kind of acceptance that this work will be done. These are not doctors caught in the act unaware. Very rarely do they return their gaze to the camera (fig. 15). The authority of medical scientists in these spaces make these images most likely consensual, at least for the professionals caught in frame.

For the patients though, even those that were caught in a more posed exposure, consent is more fraught. To think this through, I want to look at a photograph where a doctor and a patient were framed together (fig. 16). The doctor, whose face is visible, and who is working in a professional manner probably consented to the photographer taking the picture. I am less convinced that the subject, whose back is turned away in this photograph had the same ability to consent. The image of the doctor at work, whether doing treatments, research, or other aspects of their jobs (figs. 17 - 19), depends on the figure of a patient whose consent is forced or coerced. Moreover, as consent can be taken through coercive or punitive force,[^fn5] the power dynamic between patient and doctor makes any presumed agreement to and acceptance of the photographic act almost impossible. I stress consent because it is an important concept in this dissertation, which I will address in the fourth chapter (4.1.2; 4.1.4), and because it stresses a power differential between subject and researcher (0.1.4; 2.1.4). Moreover, consent, codified as it was in the post-war period, was a concept that was not dominant in medical practice: doctors did not regularly tell patients what their illness was upon diagnosis, and did not always tell patients that they were part of an experimental study.[^fn6] For doctors to be able to say ‘no’ at any point in an imaging process implies some agency over the image itself. Doctors may not expose the film in the camera, but they can say whether they should be photographed in the first place.

There is a consciousness about the operation of these images: they are documents, specimens, things that convey a message to the public. The absence of medical staff throughout the corpus speaks to a reticence to being shown in these contexts. This implicit sense of how and in what context an image operates is not conveyed to the patients who were posed without their consent.

As I finish this chapter, I will look at this strange omission in the materials, and try to glimpse the medical professionals in the moments where their presence is less obvious, but equally manufactured. I will look at the doctors when they hold their patients in place, when their hands display not just a professional touch, but also a disciplining one: one to hold the patient still for the camera, to hold the patient in place for a procedure, to hold the patient in such a way so their body may be caught for medical knowledge work (2.1.3).

-

This is not entirely true, at least in the case of photography, because some patients had agency in how they were photographed in some contexts. It is more true in the context of everyday medical diagnosis: which is not recorded, and which the clinical gaze sees through the patient.

Rawling, Katherine D. B. “‘She Sits All Day in the Attitude Depicted in the Photo’: Photography and the Psychiatric Patient in the Late Nineteenth Century.” Medical Humanities 43, no. 2 (2017): 99–110. ↩

-

Film studies has a long history discussing vouyerism, but it is outside the scope of the present study. ↩

-

Bennett, J. A. “The Social History of the Microscope.” Journal of Microscopy 155, no. 3 (1989): 267–80; Gooday, Grame. “‘Nature’ in the Laboratory: Domestication and Discipline with the Microscope in Victorian Life Science.” The British Journal for the History of Science 24, no. 3 (1991): 307–41. ↩

-

Harper’s Weekly 34. New York: November 29, 1890. 932. ↩