Introduction

Specimen Studies

0.1.1 | 0.1.2 | 0.1.3 | 0.1.4 | 0.1.5Methods

0.2.1 | 0.2.2The Structure of this Dissertation

0.3.1Tuberculosis' Visual Culture

Visual Practices in Medical Culture

1.1.1 | 1.1.2 | 1.1.3Seeing and Settling in the Sanatorium Movement

1.2.1 | 1.2.2 | 1.2.3 | 1.2.4 | 1.2.5Teaching Public Health

1.3.1 | 1.3.2 | 1.3.3 | 1.3.4 | 1.3.5Representing Doctors in Tuberculous Contexts

1.4.1 | 1.4.2Using Human Specimens in the Study of Tuberculosis

Seeing Disease in Methyl Violet

2.1.1 | 2.1.2 | 2.1.3 | 2.1.4Case Histories

2.2.1 | 2.2.2 | 2.2.3 | 2.2.4Visceral Processes

2.3.1 | 2.3.2Relation

2.4.1 | 2.4.2 | 2.4.3Arts-Based Inquiry

Introduction

3.1.1 | 3.1.2 | 3.1.3 | 3.1.4Terminal Imaginaries & Tuberculous Imaginaries

3.2.1 | 3.2.2 | 3.2.3 | 3.2.4 | 3.2.5 | 3.2.6Dermographic Opacities

3.3.1 | 3.3.2 | 3.3.3 | 3.3.4Tactical Pretensions

3.4.1 | 3.4.2 | 3.4.3Designing Opacity

A Shift towards the Anticolonial

4.1.1 | 4.1.2 | 4.1.3 | 4.1.4Refusals and Opacities

4.2.1 | 4.2.2 | 4.2.3 | 4.2.4Digital and Ethical Workflows

4.3.1 | 4.3.2 | 4.3.3 | 4.3.4 | 4.3.5Conclusion

4.4.1Coda

Prometheus Undone

5.1.1 | 5.1.2 | 5.1.3 | 5.1.4Appendix

The Tuberculosis Corpus

X.1.1 | X.1.2 | X.1.3Web Design

X.2.1 | X.2.2 | X.2.3 | X.2.4Installation Materials

X.3.1 | X.3.2 | X.3.3Index

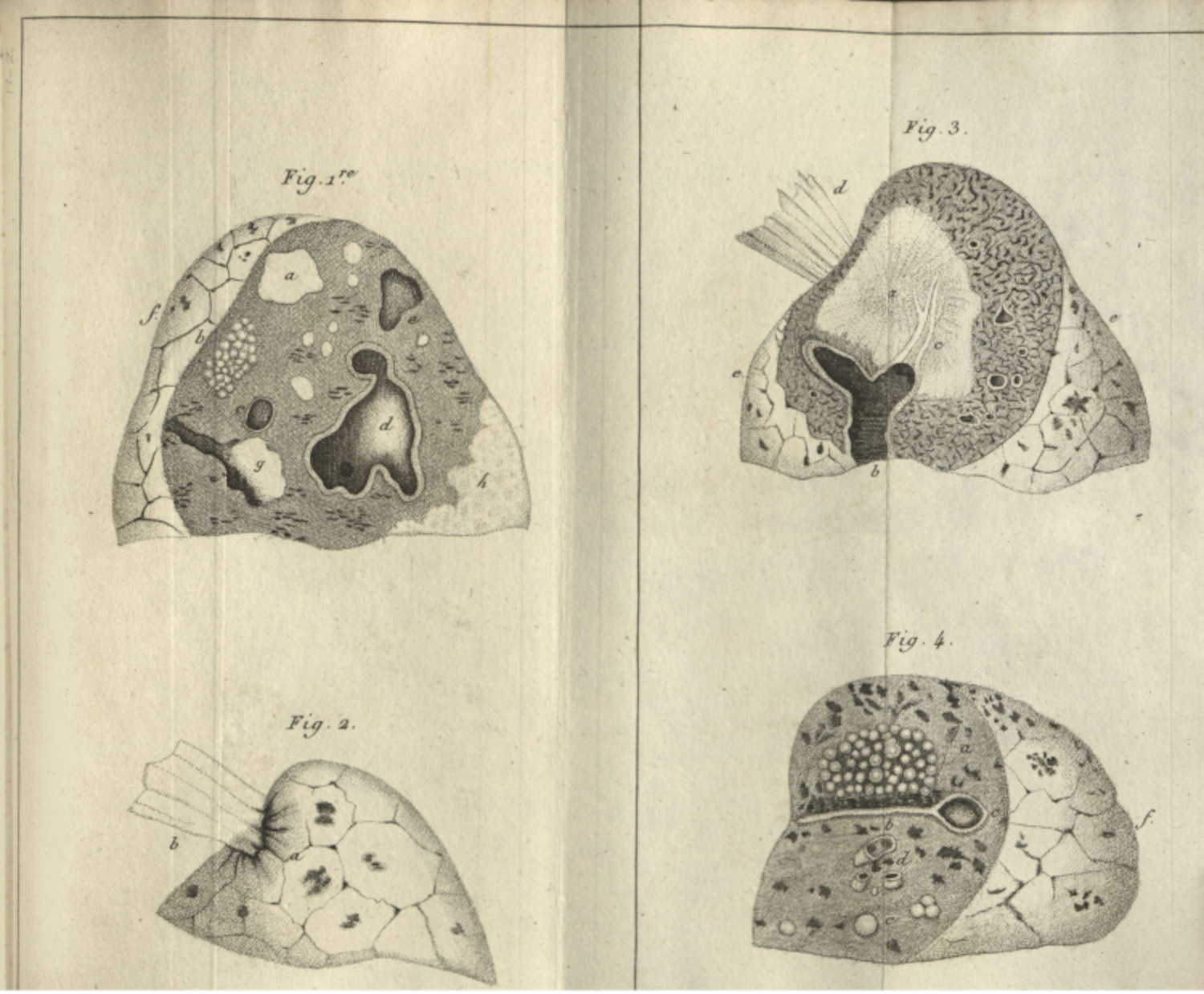

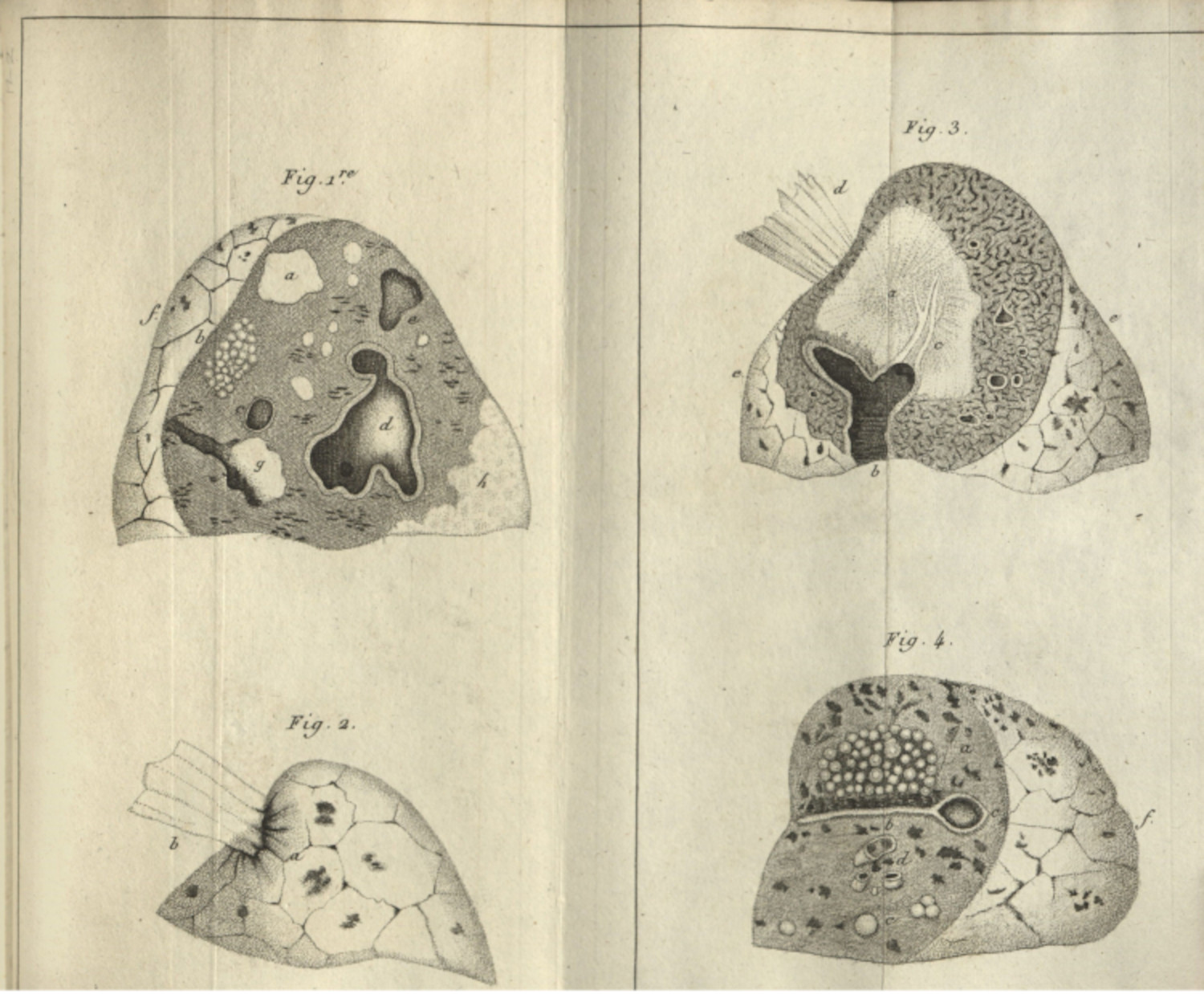

Tuberculosis is a very old disease. Famously Ramses II, Egyptian pharaoh and mummy excavated in the late-twentieth century, died of tuberculosis in 1213 BC. Consumption was understood as early as Galen, the Roman physician whose work was the basis of western medical knowledge throughout the medieval period. In its pre-microbial etiology, it was conceived as a hereditary wasting disease. Tuberculosis was named ‘consumption’ because of how patients would waste away, consumed as they were by swells of frenzied activity and feverish bouts of exhaustion (1.1.1). The use of the term tuberculosis originates from the anatomical-clinical work of René Laënnec—who died of tuberculosis himself—as he described the hardened, millet sized masses found in consumptive patients’ lungs at autopsy (2.2.2) (fig. 1).1 Its microbial etiology was argued for by Robert Koch in 1882, marking a major change in both the clinical understanding of the disease and the therapeutic approach doctors took to fighting it (2.1.1; 2.1.2; 2.1.3). These interventions included approaches to rest, exposure to fresh air and sunlight, and rigorous labor, depending on where patients were treated.2 In the mid-twentieth century, with the advent of antibiotics, tuberculosis became a curable disease; however, the disease returned to international prominence because of the HIV/AIDS epidemic of the 1980’s and 1990’s, alongside the rise of drug-resistant TB.3

This is a broad sketch of the history of tuberculosis, one which avoids certain nuances which deserve their own approaches. While tuberculosis is an ancient disease—and a disease that affects many animals in addition to humans—it is important to understand that the historical and cultural understandings about the disease were very different than how it is understood today. Bruno Latour, writing of Rames II’s tuberculosis diagnosis, reminds his readers that while the symptoms of tuberculosis were similar for the Egyptian pharaoh, the ancient doctors of the period understood the disease differently: “An isolated Koch bacillus is also a pragmatic absurdity since those types of facts cannot escape their networks of production either. Yet we seem to believe they can, because for science, and for science only, we forget the local, material, and practical networks that accompany artifacts through the whole duration of their lives.”4 The social constructions of a disease—the cultural, folk, and scientific understandings of its phenomena—deserve attention. Also, as became apparent in the Covid-19 pandemic, diseases evolve over time. The omicron and delta strains were the same disease, but they had different and unique symptoms. Infectious diseases, even when their causes are determined, are not stabile objects. How those diseases are framed by scientists, by communities and individuals, within literature (1.1.1), and in a social imagery (1.2.1; 2.2.2), impact how cultures care for patients, understand the disease, and respond to it.

One of the things that trips me up, when I look at the sometimes-abhorrent practices of medical practitioners of the twentieth century, and when I look to the decidedly shaky clinical record the sanatoria system (1.2.1; 1.2.3), is that I forget that tuberculosis was basically incurable at the turn of the twentieth century. Patients would improve after weeks or months in treatment, only for the disease to reappear days, weeks, or years after the patient’s release from a sanatorium.5 The development of antibiotics in the post-war period could be called a miracle, effectively curing the chronic, often fatal malady; and so when I write incredulously of these treatments, it comes from the privileged perspective where tuberculosis is not, and will not be a major actor on my own life, nor an actor for many of my American or western European colleagues (1.1.1).

I bring this up because the cultural context is informed by curative practices, which are in turn informed by scientific and ideological conceptions about the disease. This dissertation looks at tuberculosis beginning in 1882, the year Robert Koch linked the malady to Mycobacterium tuberculosis (2.2.1; 2.2.2; 2.2.3), when the global health system readdressed its understanding of the disease. The shift from hereditary to microbial cause meant that tuberculosis could be prevented and could conceivably be cured. It also meant that tuberculosis could be imagined with all sorts of xenophobic metaphors of conquest and invasion (2.3.1), and it could be rhetorically leveraged as a danger to the working population and body politic (1.3.5). This dissertation mostly focuses on tuberculosis in the United States, dipping into discourses in the United Kingdom because they share the same language and directly influenced American research and practice. Importantly for doctors in the United States, trained as they were in race science and eugenics (1.3.5),6 Koch’s microbial findings were viewed with a certain amount of skepticism. These doctors more closely associated the susceptibility of patients to the heredity of the patient—the soil—rather than the bacteria—the germ.7 This ideology was informed by the rise of eugenics in the same period (1.3.5), and was entangled with classed and abled assumptions of who was sick and who was healthy; who was clean and who was dirty; and who was safe to be around and who was a danger to society (1.3.4; 1.3.5).

I chose tuberculosis as the subject of this dissertation because of these social valencies. I also chose it because the link of the disease to Mycobacterium tuberculosis occurred in the same moment as the professionalization of medicine in the United States. While it would be in the twentieth century when the nation would become the center of medical knowledge making, the late nineteenth century saw the centralization of medical schools, the establishment of modern pharmaceuticals through the work of Eli Lilly and others, and the explosion of medical facilities from hospitals to sanitaria across the nation (1.2.3; 1.2.4). More than this, tuberculosis was instrumental in the formulation of insurance-based healthcare, with national-scale approaches to curing the workforce being adopted in the United Kingdom and Germany at this same time, and with private insurance companies selling tuberculosis policies in the United States. Tuberculosis did not cause any of these practices, but it was a significant player in discussions around health.

These connections to prominent historical and cultural shifts at the turn of the twentieth century were the main driver for this dissertation, but I would be remiss, and untruthful, if I omitted another main organizing structure for this study: all of the images, publications, and materials used for this project were published on or before 1926, making them freely available in the public domain.8 This meant that I would be free to access the required materials digitally,9 and that I could tinker with, remix, revise, and otherwise creatively examine these photographs, books, and pamphlets without legal repercussions. Arts-based and practice-based interventions (3.1.3; 4.1.2) were central to the exploratory phase of this project, and they were only possible because of the legal framework established through the public domain.10

These publicly available materials also formed the tuberculosis corpus and the image dataset, which was developed from that collection of primary materials. The term corpus is used in computational linguistics and textual analysis to describe a collection of books that are then subject to computer-based analysis. The tuberculosis corpus that I developed for this dissertation is a collection of books, articles, pamphlets and journals which were published between 1880 and 1926 and which focus on tuberculosis (X.1.1; X.1.2). The image dataset was developed from this corpus, and it compiles every image—photograph, x-ray, or illustration—which appears in those publications (X.1.3; X.1.4). I will often describe these two projects together because the image dataset was developed directly from the tuberculosis corpus.

-

Laënnec, Rene Theophile Hyacinthe. Treatise on the Diseases of the Chest in Which they are Described According to their Anatomical characters and their Diagnosis Established on a New Principle by Means of Acoustick Instruments, with plates. Translated by: Forbes, John. Philadelphia: James Webster, 1823. ↩

-

Bryder, Linda. Below the Magic Mountain: A Social History of Tuberculosis in Twentieth-Century Britain. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1988. ↩

-

It is in this period that many of the best histories of the disease were penned, as the authors were responding directly to these health crises.

Bryder, Linda. Below the Magic Mountain; Feldberg, Georgina D. Disease and Class: Tuberculosis and the Shaping of Modern North American Society. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1995. ↩

-

Latour, Bruno. “On the Partial Existence of Existing and Nonexisting Objects.” In Biographies of Scientific Objeccts, edited by Lorraine Daston. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000. 250. ↩

-

Edward Livingston Trudeau, founder of the Adirondack Cottage Sanitarium is a perfect example of this, having recovered from tuberculosis in the 1870’s, but subsequently dying of tuberculosis decades later in 1915. ↩

-

Willoughby, Christopher D. E. Masters of Health: Racial Science and Slavery in U.S. Medical Schools. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2022; Washington, Harriet A. Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present. New York: Harlem Moon & Broadway Books, 2006. ↩

-

Feldberg, Georgina D. Disease and Class: Tuberculosis and the Shaping of Modern North American Society. ↩

-

When I began this project and collected the materials used in the tuberculosis corpus (X.1.1; X.1.2), the creative works from 1926 and before were considered in the public domain. It has since been expanded within the United States, with materials published before January 1, 1929 now available for replication, remix, and revision. ↩

-

This was especially important because I began the primary research for this project in fall 2021, when access to archives was almost impossible because of the Covid-19 pandemic. ↩

-

The public domain is a really slippery topic.

Christen, Kimberly. “Does Information Really Want to Be Free?: Indigenous Knowledge Systems and the Question of Openness.” International Journal of Communication 6 (2012): 2870–93. ↩