Introduction

Specimen Studies

0.1.1 | 0.1.2 | 0.1.3 | 0.1.4 | 0.1.5Methods

0.2.1 | 0.2.2The Structure of this Dissertation

0.3.1Tuberculosis' Visual Culture

Visual Practices in Medical Culture

1.1.1 | 1.1.2 | 1.1.3Seeing and Settling in the Sanatorium Movement

1.2.1 | 1.2.2 | 1.2.3 | 1.2.4 | 1.2.5Teaching Public Health

1.3.1 | 1.3.2 | 1.3.3 | 1.3.4 | 1.3.5Representing Doctors in Tuberculous Contexts

1.4.1 | 1.4.2Using Human Specimens in the Study of Tuberculosis

Seeing Disease in Methyl Violet

2.1.1 | 2.1.2 | 2.1.3 | 2.1.4Case Histories

2.2.1 | 2.2.2 | 2.2.3 | 2.2.4Visceral Processes

2.3.1 | 2.3.2Relation

2.4.1 | 2.4.2 | 2.4.3Arts-Based Inquiry

Introduction

3.1.1 | 3.1.2 | 3.1.3 | 3.1.4Terminal Imaginaries & Tuberculous Imaginaries

3.2.1 | 3.2.2 | 3.2.3 | 3.2.4 | 3.2.5 | 3.2.6Dermographic Opacities

3.3.1 | 3.3.2 | 3.3.3 | 3.3.4Tactical Pretensions

3.4.1 | 3.4.2 | 3.4.3Designing Opacity

A Shift towards the Anticolonial

4.1.1 | 4.1.2 | 4.1.3 | 4.1.4Refusals and Opacities

4.2.1 | 4.2.2 | 4.2.3 | 4.2.4Digital and Ethical Workflows

4.3.1 | 4.3.2 | 4.3.3 | 4.3.4 | 4.3.5Conclusion

4.4.1Coda

Prometheus Undone

5.1.1 | 5.1.2 | 5.1.3 | 5.1.4Appendix

The Tuberculosis Corpus

X.1.1 | X.1.2 | X.1.3Web Design

X.2.1 | X.2.2 | X.2.3 | X.2.4Installation Materials

X.3.1 | X.3.2 | X.3.3Index

Susan Sontag’s Illness as Metaphor examines the ways sick individuals are viewed following a diagnosis with a disease. Written after her own experience with breast cancer, the essay reflects on how isolating and stigmatizing it was to go through chemotherapy treatment in the 1970s. She thought about the kinds of language that was used around cancer, and the ways the disease was represented in the contemporary discourse. Her essay was, also, a comparative one, using tuberculosis at the turn of the twentieth century as a foil. Tuberculosis was popularly conceived as a wasting disease, for Romantics, poets and artists who burnt out young, as they frenziedly lost weight until they were left bedridden and on death’s door (1.2.1). She writes,

TB sufferers may be represented as passionate but are, more characteristically, deficient in vitality, in life force. . . . TB is celebrated as the disease of born victims, of sensitive, passive people who are not quite life-loving enough to survive. . . . And while the standard representation of a death from TB places the emphasis on the perfected sublimation of feeling, the recurrent figure of the tubercular courtesan indicates that TB was also thought to make the sufferer sexy.1

Sontag played with popular imaginations of tuberculosis not only to comparatively reflect on the alienation she felt as a cancer patient, but also to think about how the sick are conisidered at a cultural scale: the ideas about specific diseases manifest in discourses outside the realm of medicine, scientific literature, and hospital wards. In some ways the essay fits well next to the critiques of Phillipe Ariés, Elizabeth Kübler-Ross, and Cisely Saunders, death studies thinkers who penned research in the post-war period that critiqued the medicalization of sick patients, and the mediation of death in medical contexts (2.1.4).2 Biomedicine—the dominant medical knowledge system which guides contemporary discourses around health and wellness globally—has been attacked for decades because of its often cruel, ambivalent, and alienating practices. Sontag’s essay, as well as its follow-up essay on the metaphors around AIDS, critiques both the medicalization and isolation of cancer patients and the stigmas which swirl about the disease that emerge from both medical sources and the broader public’s understanding about the disease.

Tuberculosis is an excellent choice to use as a prop and contrast for Sontag’s essay. The disease is not a straw man in Sontag’s argument, as it is broad enough and so present in the public consciousness that, even after the advent of antibiotics, most people are aware of its history and cultural impact.3 Not unlike its recurring infection in the body of a patient, tuberculosis always returns: by way of the AIDS crisis, the advancement of drug resistant TB, and global inequities in care.4 The disease remains in the public consciousness, both in the recollections of loved ones who have memories of family members with the disease,5 but also in the ways tuberculosis is leveraged as a exclusion agent (1.3.5). Many of my colleagues who traveled to the United States for school have told me about the mandatory TB screenings they had to take before they could be allowed in the country.6 The popular imagination of the disease resides as an afterimage, nestled into discourses of public health, care standards, popular media, and xenophobic debates around immigration. This luminescent remnant was produced as a result of broader cultural, scientific, and governmental forces, which focused on tuberculosis in the late nineteenth century. Such images of tuberculosis were produced in equal measure by a change in knowledge around the disease (2.1.3), by the popularization of the sanatorium7 treatment (1.2.1; 1.2.3), by the adoption of germ theory (2.1.1; 2.1.2), by the emergence of public health approaches to medicine (1.3.1; 1.3.4; 1.3.5), and by an active volunteer network fighting to rid the nation of tuberculosis.

This popular and social understanding was informed by, and in turn influenced, the scientific imagination of the disease. I use the phrase scientific imagination to stress the social construction of health (0.1.3),8 and to note the cultural influence of the disease prior to Robert Koch’s bacteriological studies (2.1.1; 2.1.2; 2.1.3), when it had been considered a hereditary, wasting disease.9 For the majority of the nineteenth century, tuberculosis was associated with those with an artistic disposition—the Romantic poet John Keats being the most cited example.10 Those with the disease were thought to burn bright and fast and be consumed over months or years. These conceptions of heredity, as well as ideas regarding a set limit of energy a human had in their lifespan, persisted into the twentieth century, with familial disposition to the disease becoming a central conceit for germ versus soil arguments11—where the embodied disposition of a patient was thought to be more important for a tuberculosis infection than Mycobacterium tuberculosis itself (1.3.5).12

An imagined version of tuberculosis does not loom large in the medical memory alone, though. It is also present in the popular imagination, in part due to these cultural influences and in part due to its ebb and flow as a problem in global health.13 While readers of this dissertation may have lingering memories of the disease, it is also situated in a significant in a broader historical and cultural context which an interdisciplinary audience may only be aware of in passing.

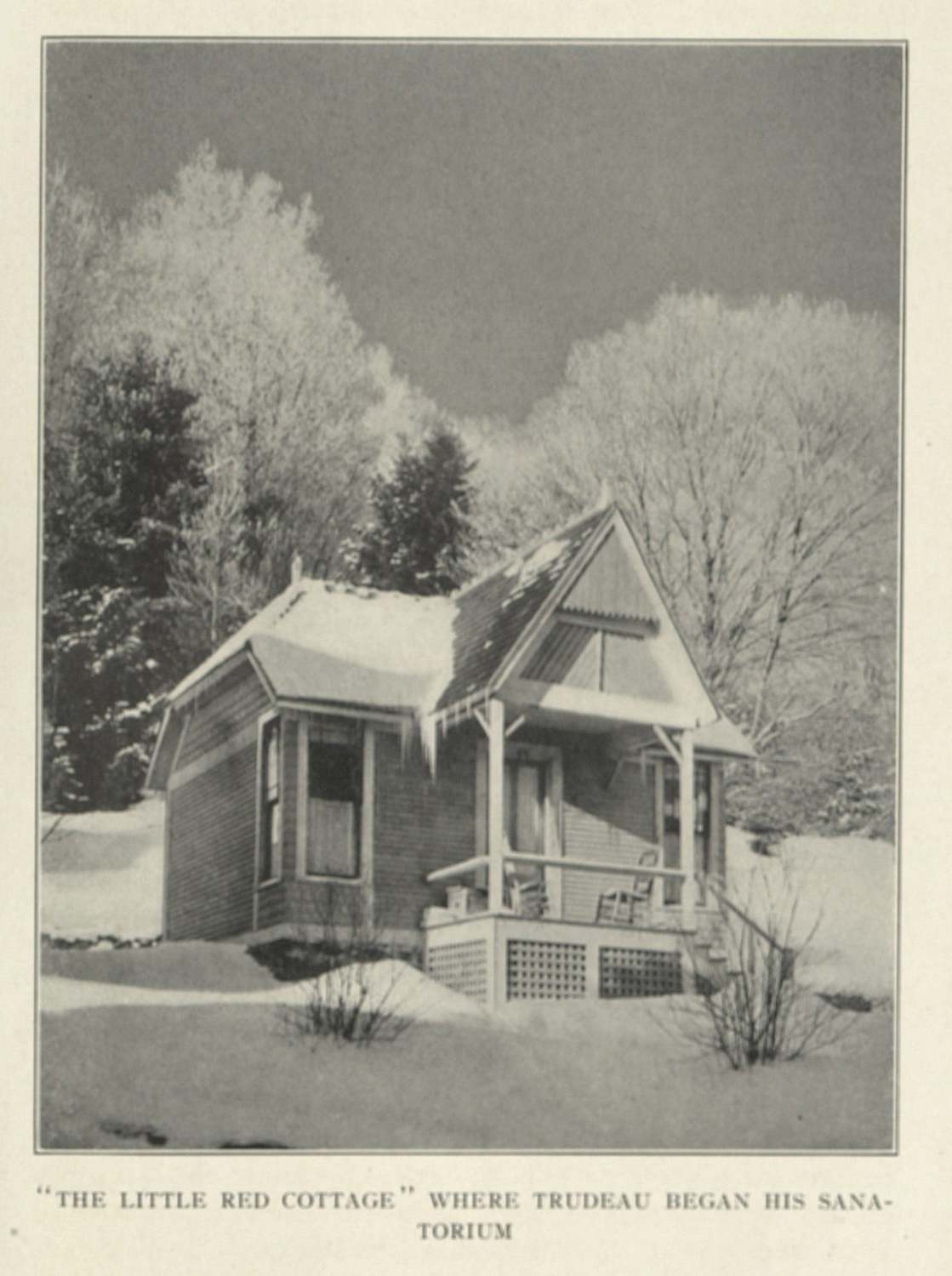

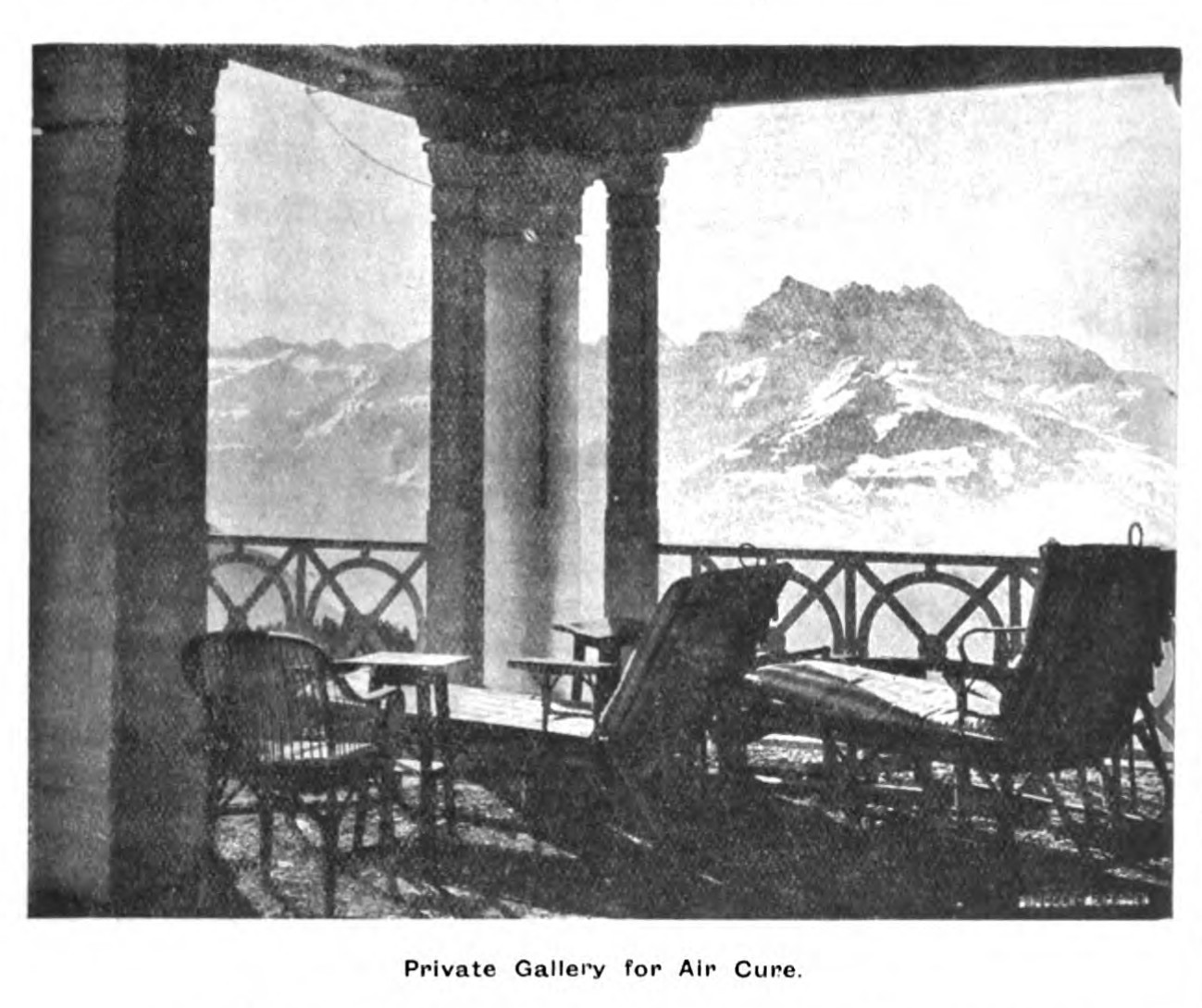

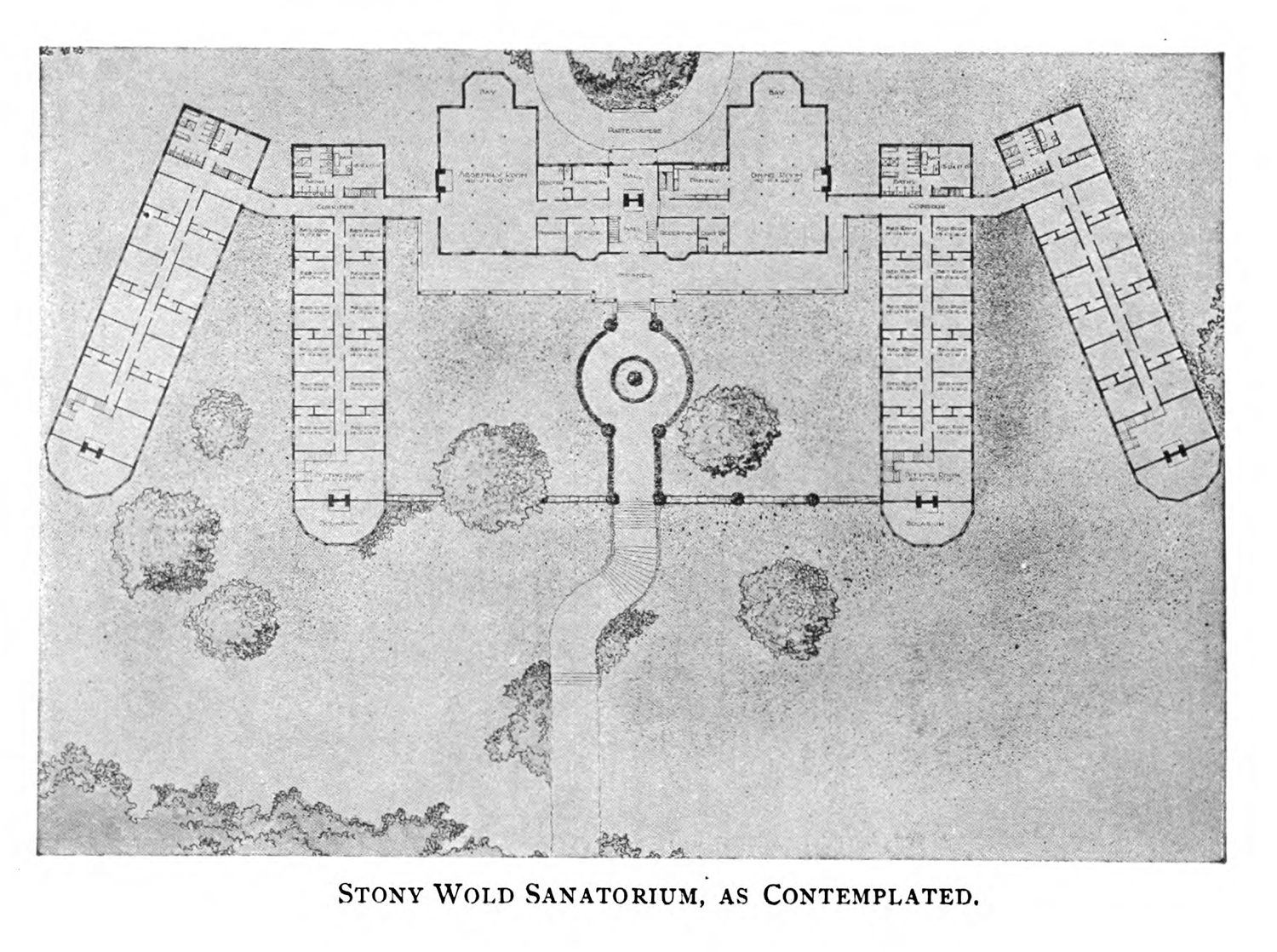

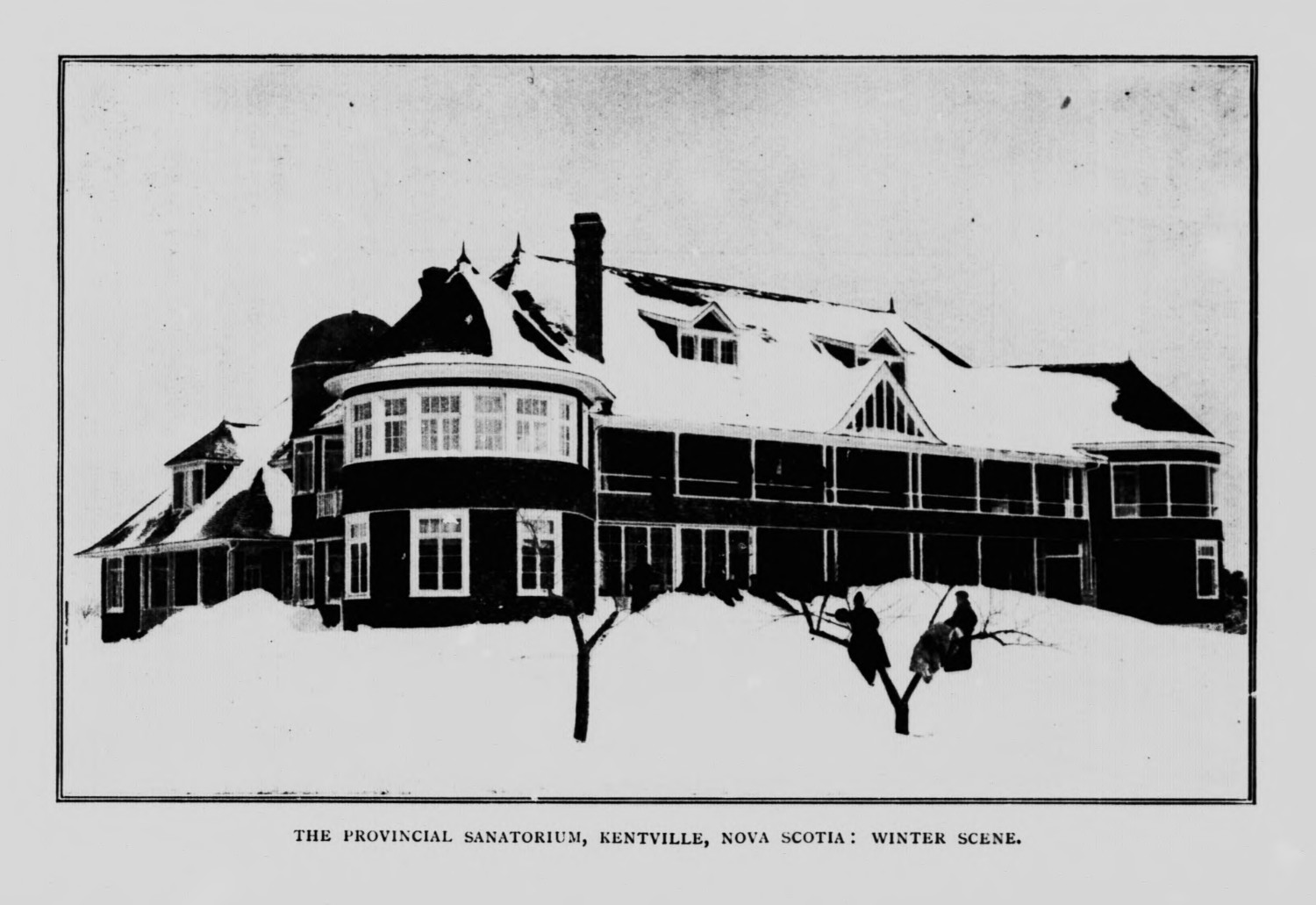

Perhaps most important is that, in the development of the dataset for this dissertation (X.1.3), I found myself inundated with images that did not correspond to my own assumptions about medicine’s visual culture (1.1.2; 2.2.2). I had assumed that the majority of images would depict to the specimen at different scales—cellular images, wet specimens, and full body pathological portraits—and in different media—illustrations, photographs, and x-rays. What I did not expect was that scientific journals also published about sanatoria, arguing about the merits of specific floor plans (1.2.4); promoting their facilities (1.2.3); gazing at poor, disabled, or otherwise othered patients (1.3.1; 1.3.4; 1.3.5). They were looking at and defining the broader cultures around tuberculosis beyond the remit of the specimen.

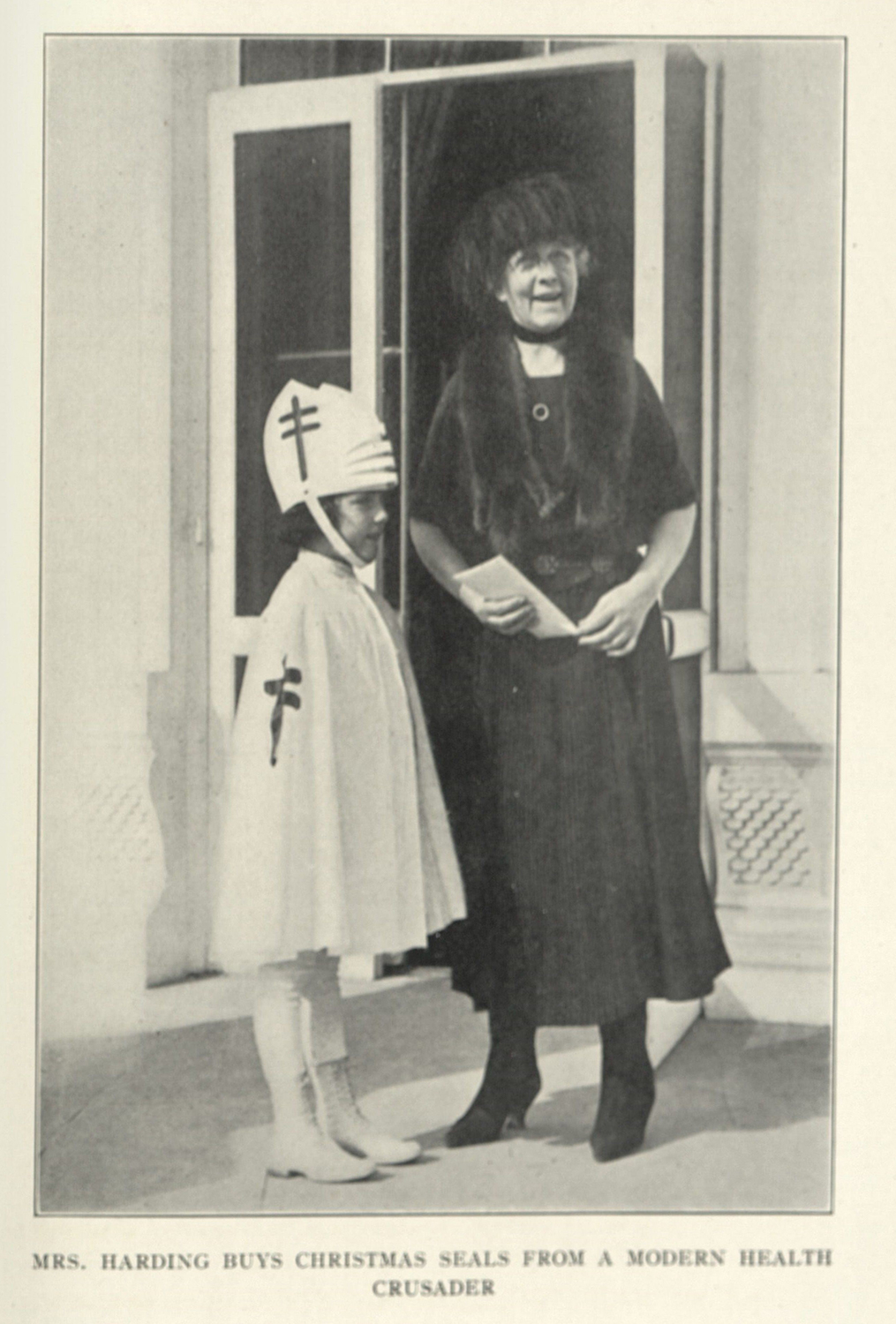

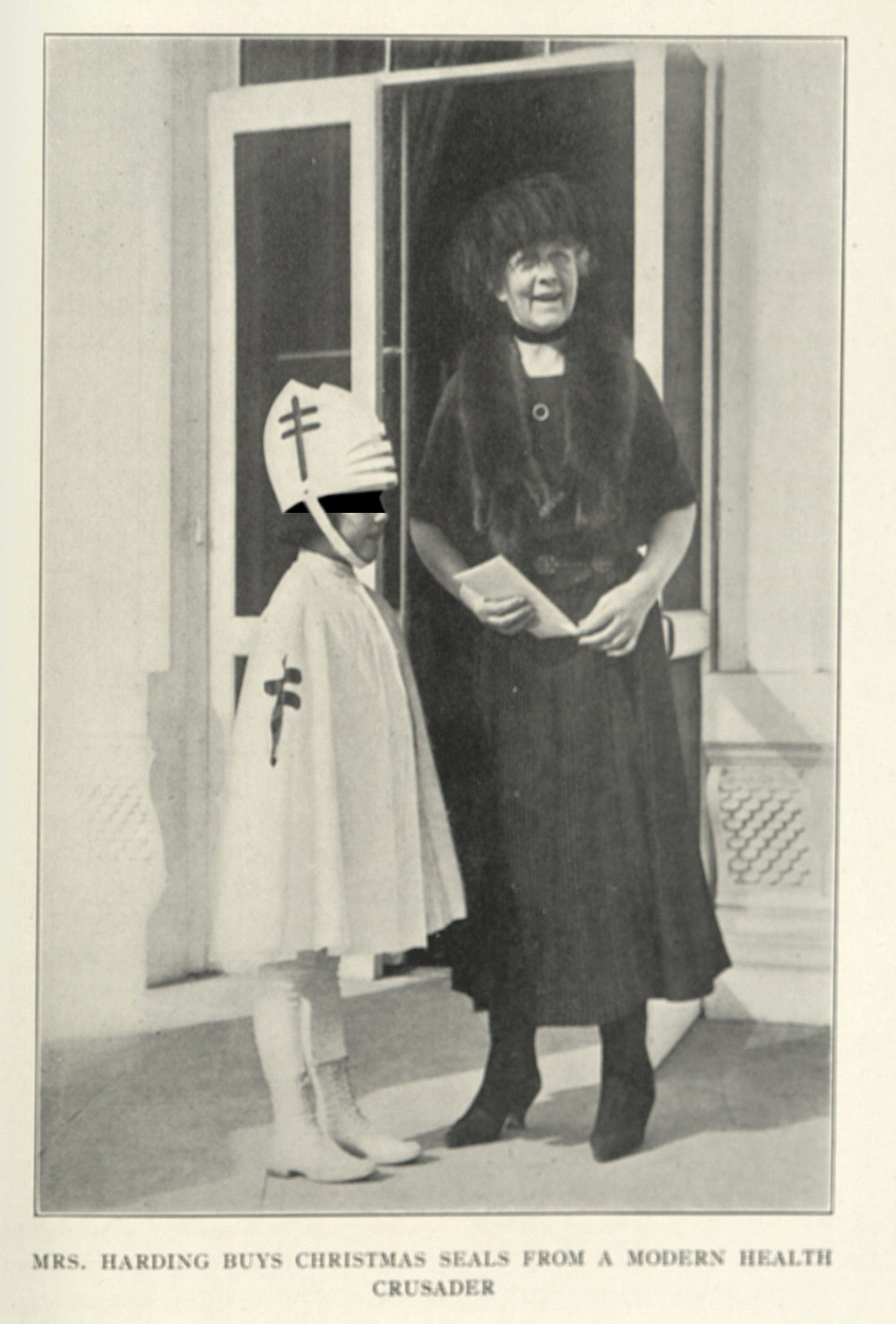

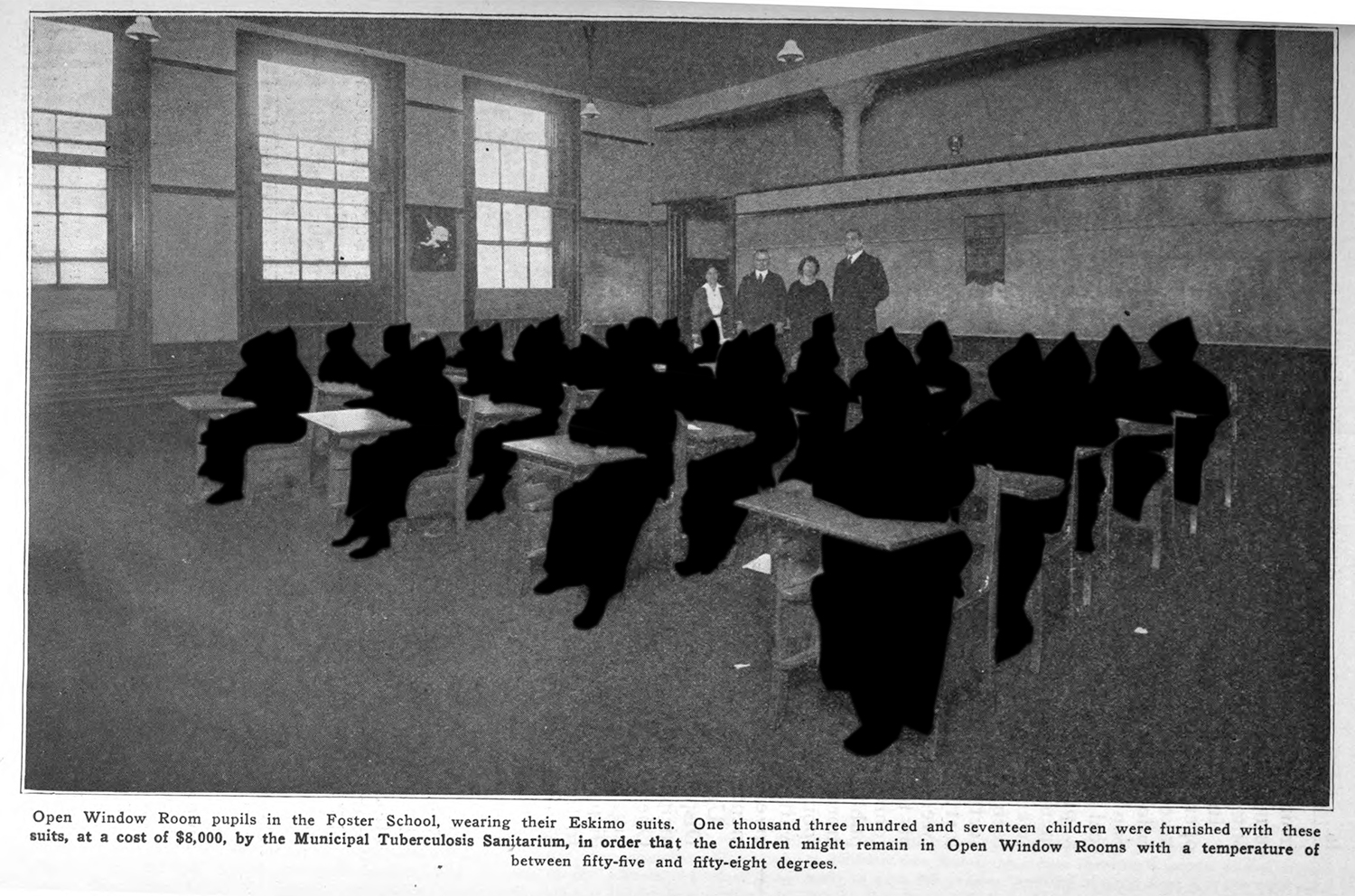

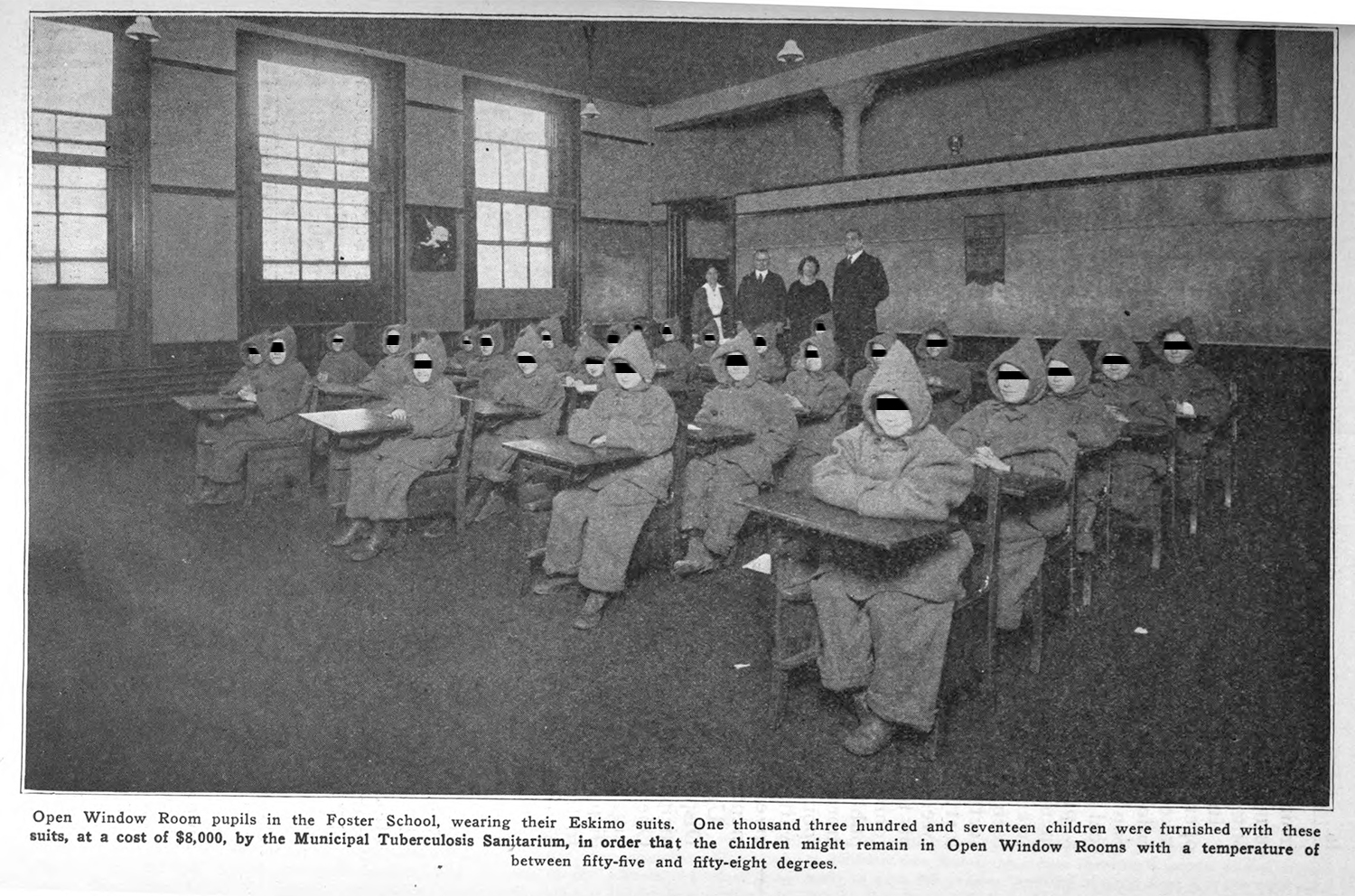

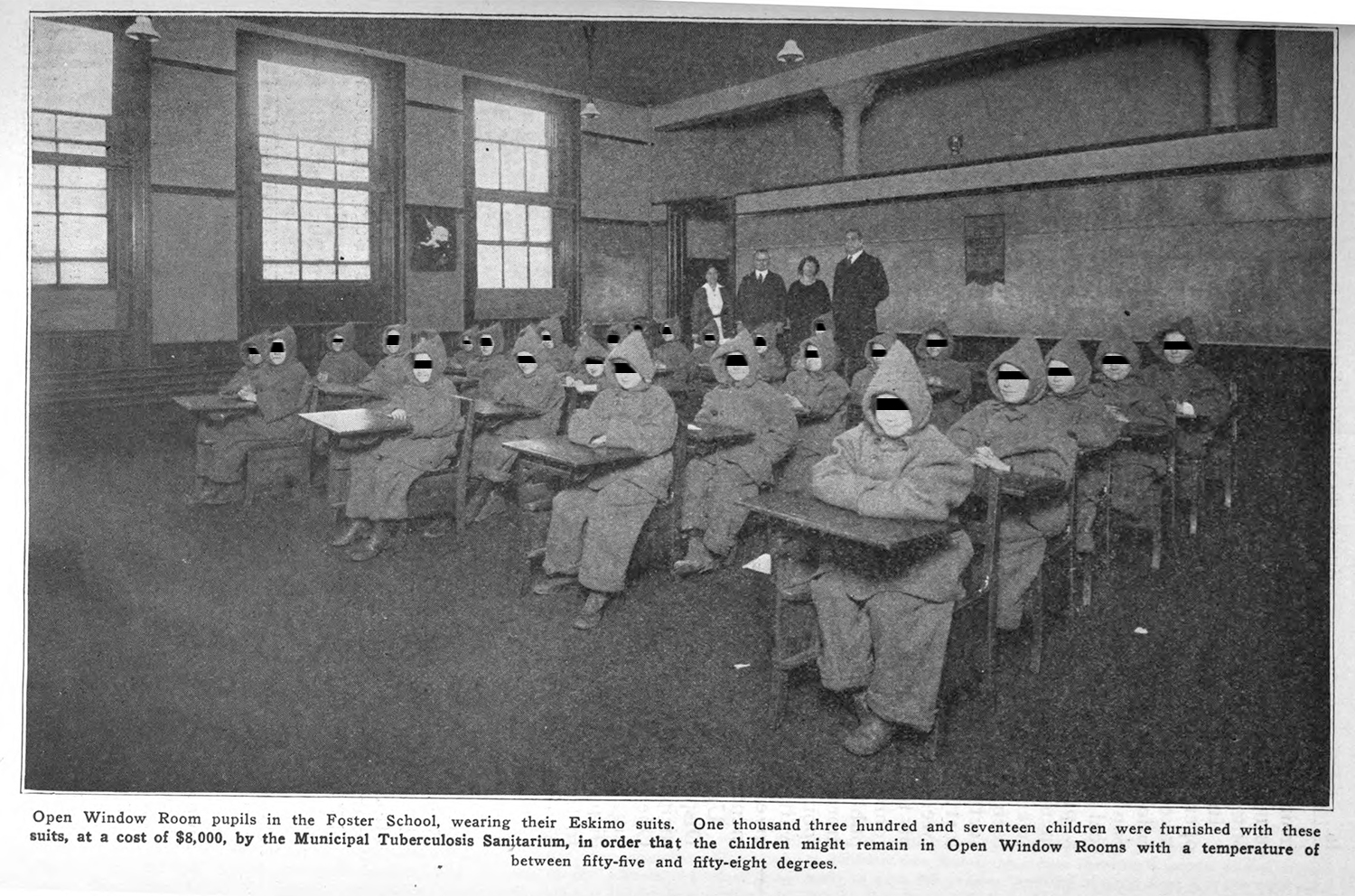

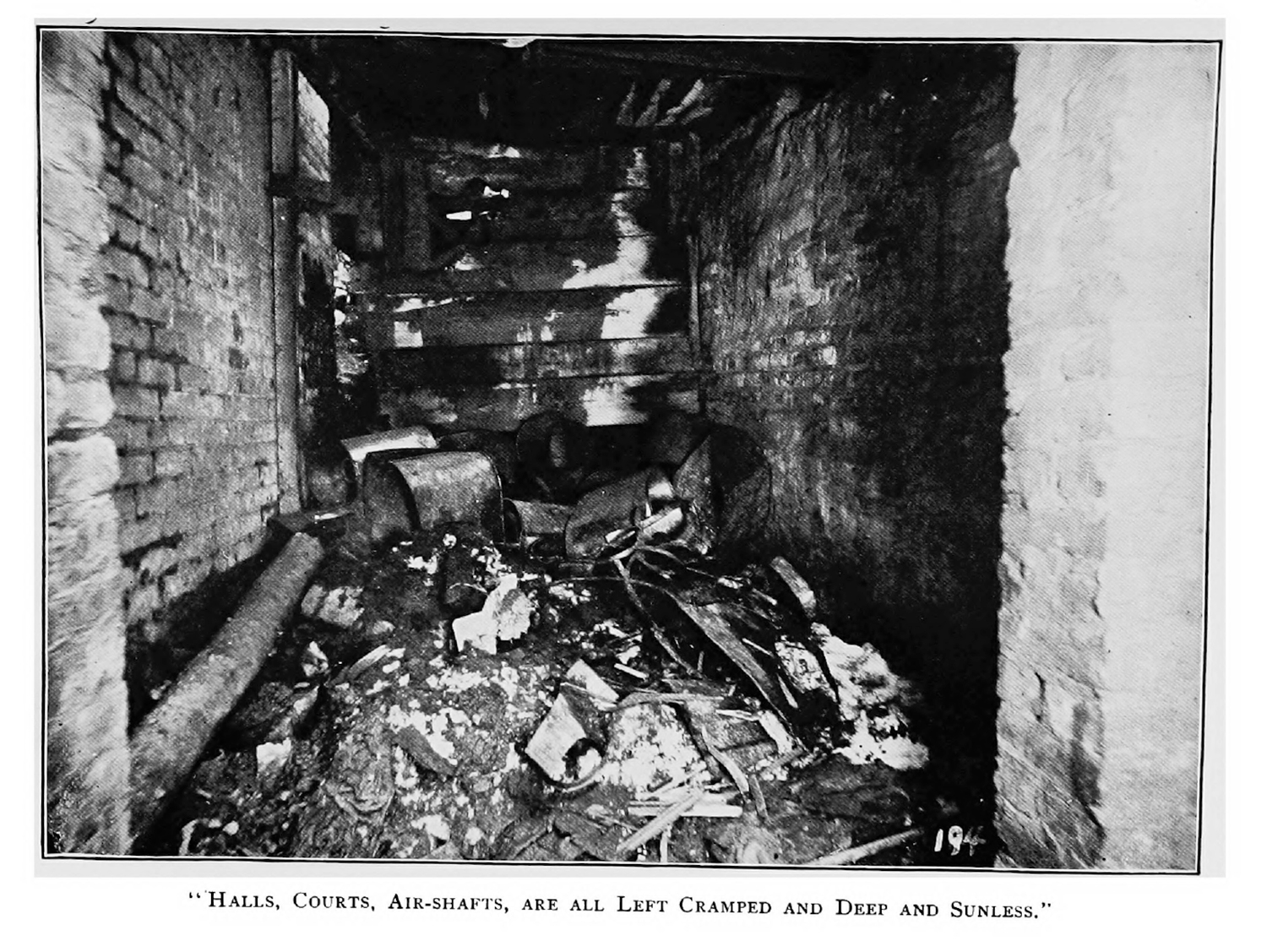

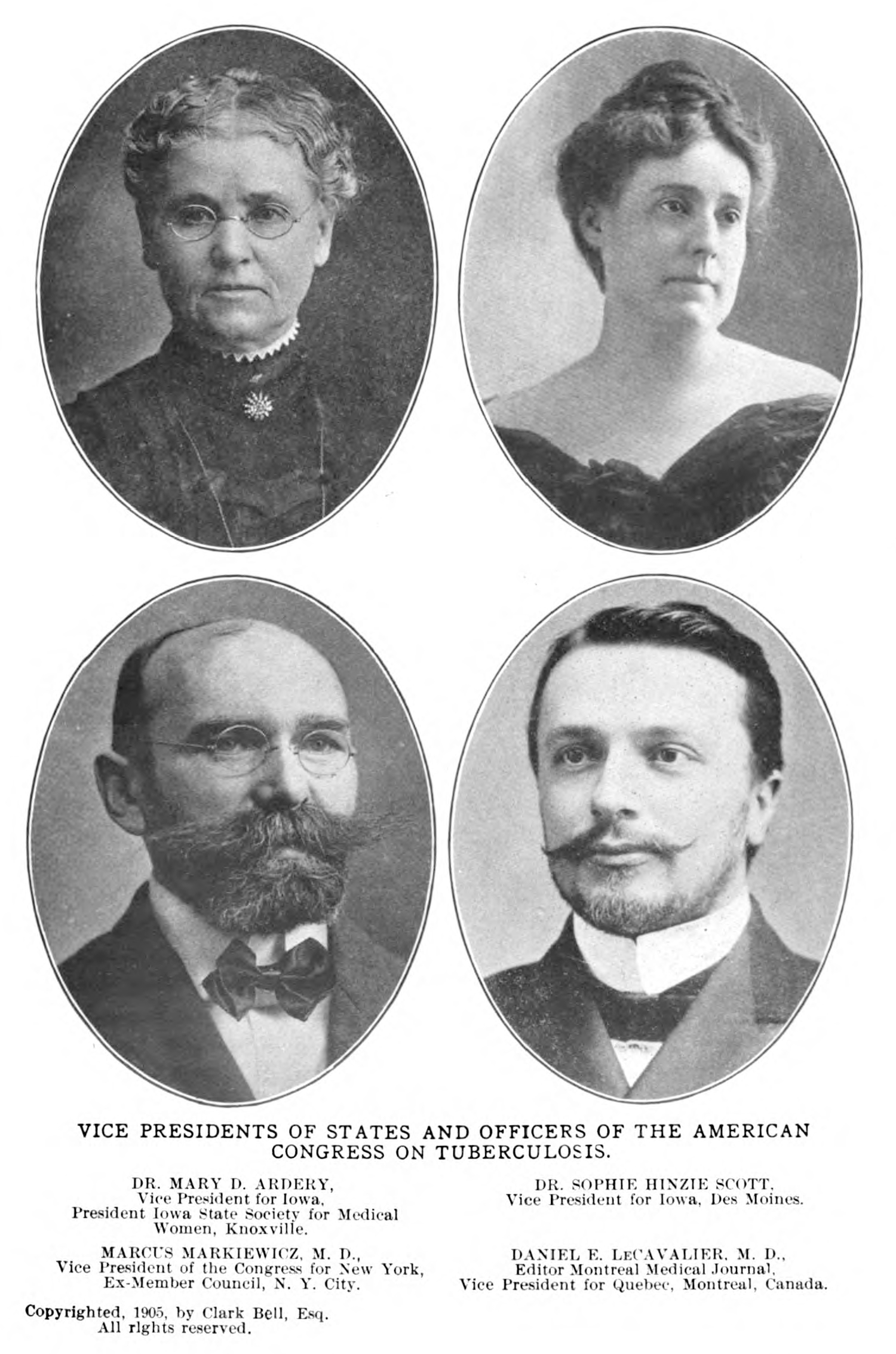

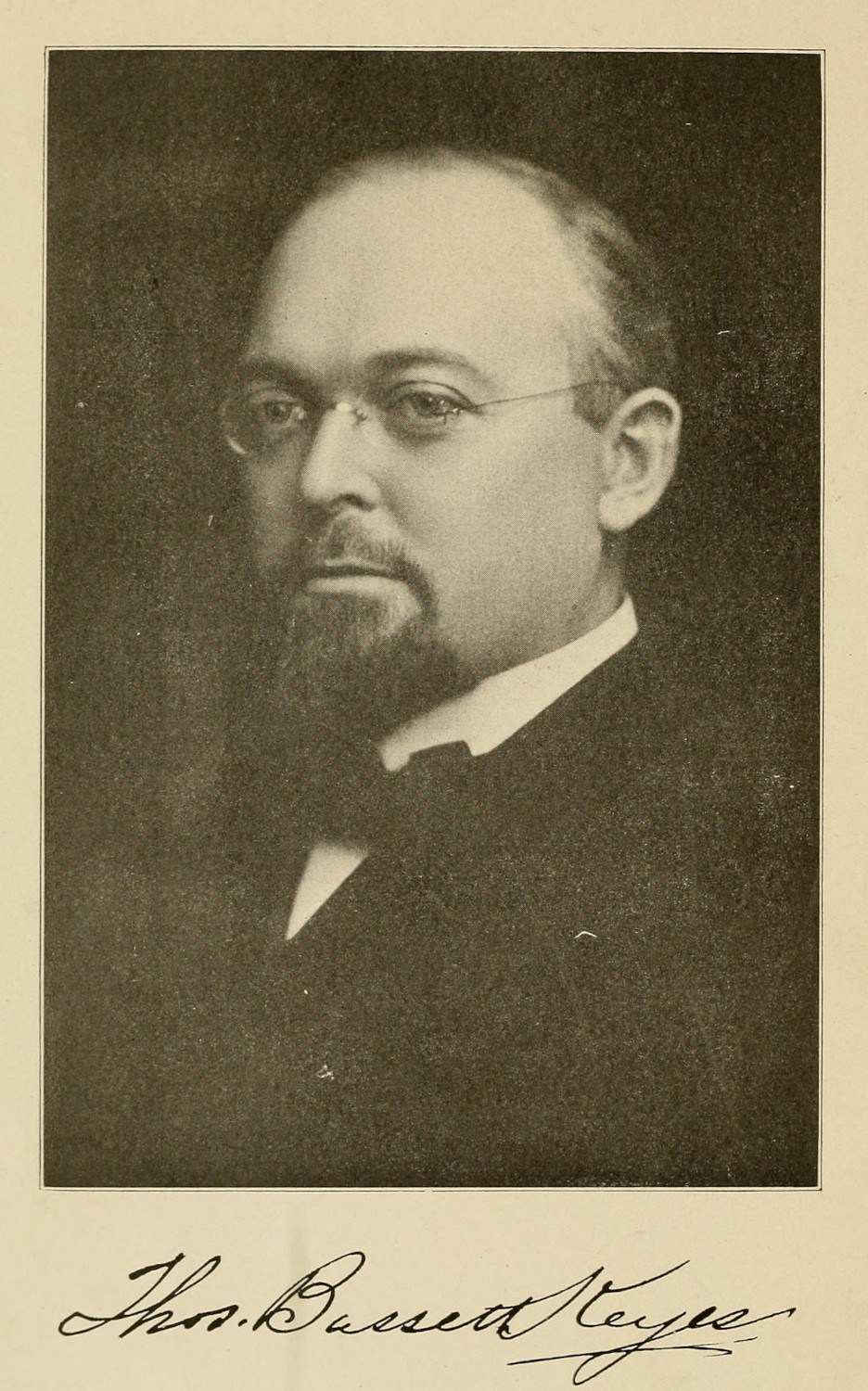

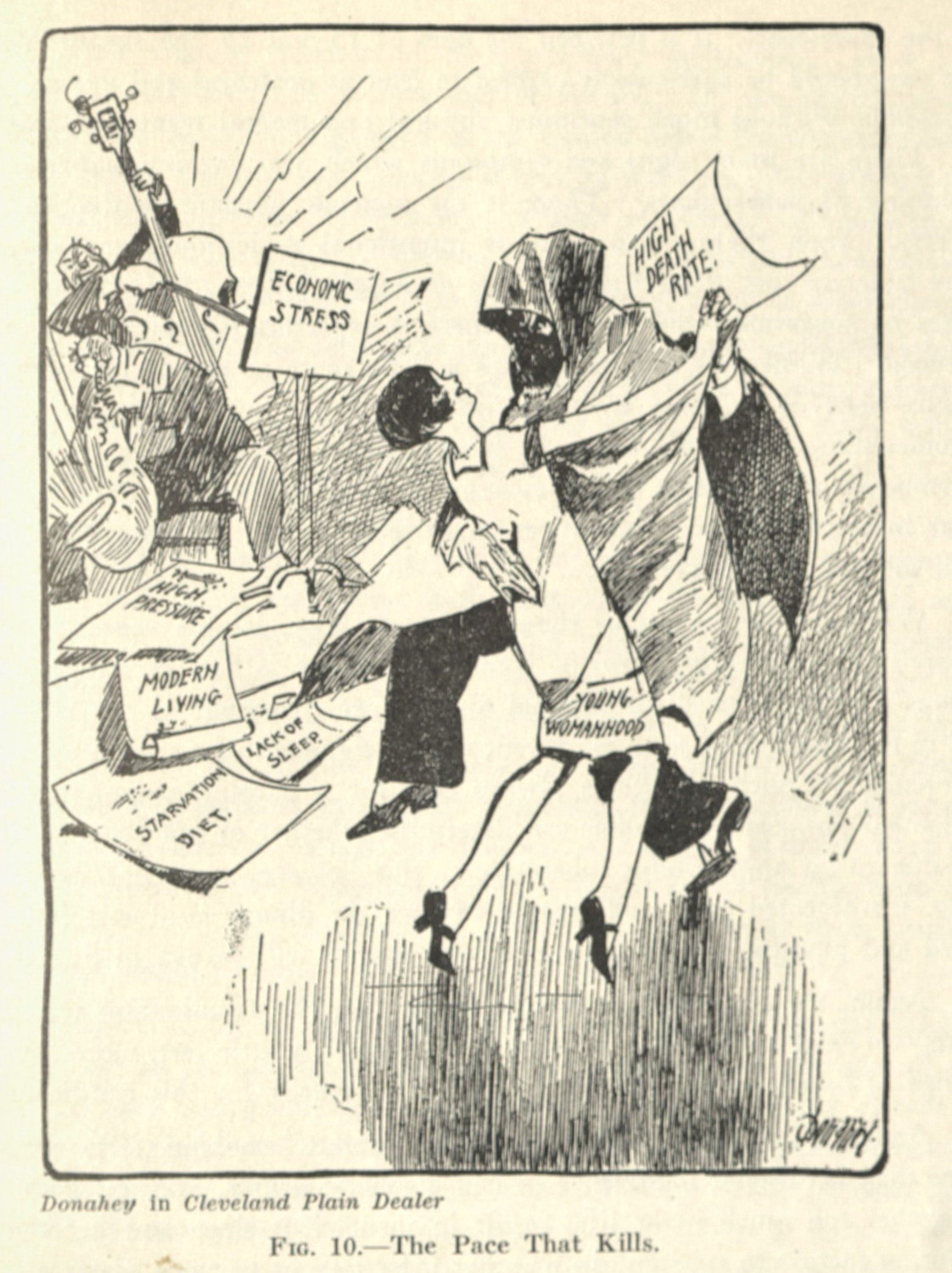

This chapter, then, works to foreground the non-specimen images which litter the tuberculosis image data set (X.1.3). What does a child selling postage seals (fig. 1), an architectural floor plan for a sanatorium (fig. 5), an image of a filthy room (fig. 6), images of children studying in heavy coats (fig. 2), and a photograph of a cottage (fig. 3) have to do with the scientific understandings of the disease? What about a photograph of an idyllic mountain resort (figs. 4 & 7), a portrait of a doctor taken for a conference (figs. 8 & 9), or a graphic of a flapper dancing with death (fig. 10) have to do with the ways doctors saw and treated their patients?

Early on in my research, I had assumed that scientific medicine was defined by the clinical gaze. This singular way of seeing the sick patient emphasizes contrasts between a healthy ‘normal’ anatomy and unhealthy ‘abnormal’ pathology, resulting in the alienation and objectification of a sick patient (1.1.2; 2.2.2). Visual culture scholars like Katherine Waldby, Jose van Djick, Erin O’Connor, and Lisa Cartwright have convincingly articulated the ways clinical visuality has been embraced in medical practice and in diagnostic technologies.14 My assumption was that most of the images in the corpus would correspond with the alienating, dehumanizing clinical gaze and its technological mediation in the clinical photograph.15 These images, being non-specimen images,16 were outside the scope of my initial research, but muscled their way in as a prominent practice which deserved attention.

This chapter addresses this surprising observation with a series of questions: what are some of the broader assumptions which encircle the treatment of tuberculosis? How are these reproduced in visual media? How do they display differing visual practices in the history of medicine (1.1.2; 2.2.2)? And in what ways do these images reinforce the classist, racist, and ableist ideologies in the health sciences (1.3.5)?

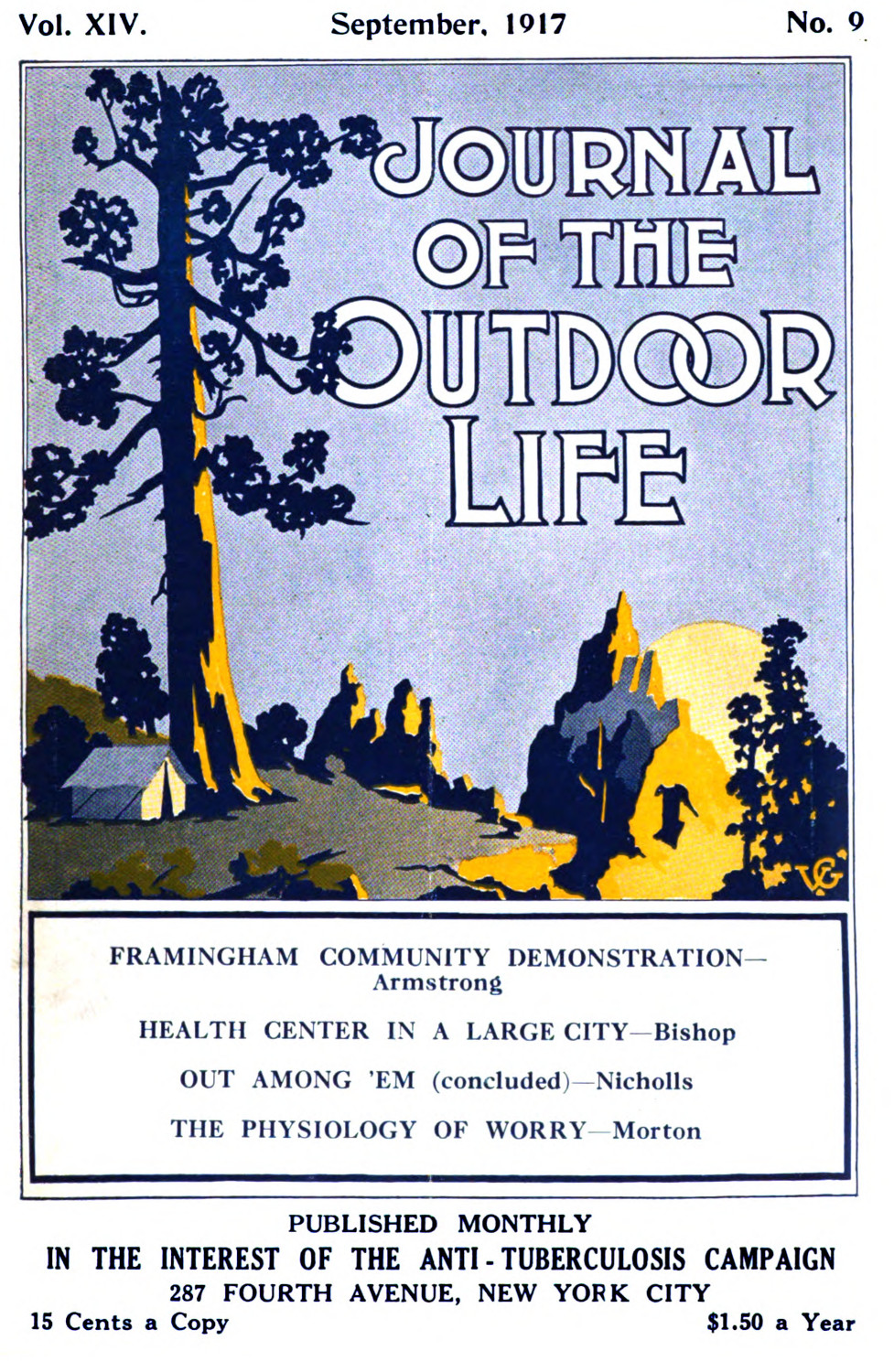

I ask these questions first because of the implicit connections between tuberculosis research and the other cultural actors producing images. Some of the visual material is closely related to scientific research, as with the cases of material in public-facing magazines published by sanatoria with research capabilities (The Sanatorium and the first few volumes of The Journal of Outdoor Life) (fig. 11). Other materials were linked to public health and volunteer organizations like the Anti-Tuberculosis Health League or the Charity Organization Society of the City of New York, and even more were public-facing books that were meant to help patients with tuberculosis find sanatoria, understand how to treat their loved ones, or provide knowledge regarding hygiene (1.3.4). Beyond this, even more images came from self-published or regionally published materials that may or may not have any association with the scientific discourses around the disease (fig. 12). This broad range of publications speaks also to a wide array of writers and readers. Where a visual practice—like the clinical gaze—may be trained by a majority of the actors in the discourse, many of the other actors—public health officials, volunteers, lay people, and patients—bring their own ideologies, preconceptions, and visual approaches into the broader conversation.

In this chapter I will wrangle the sometimes disparate threads which knot around the non-scientific representations of tuberculosis in this period. I pursue two arguments: first, in building on the excellent but narrow scholarship by my peers who analyze medicine and its ways of seeing, I stress a need to look at medicine’s visual cultures in the plural. Medicine has never practiced a singular visual culture, one overtly defined by the clinical gaze. By opening this discourse to competing, overlapping, contested visual practices, I encourage future scholars to explore the idiosyncratic visual modes leveraged by medical doctors, patients, and others working in healthcare.17 Moreover, where this chapter addresses tuberculosis, I acknowledge that the cultural landscape which emerged around other diseases—like the AIDS epidemic, cancer research, the 1918 influenza epidemic, or Covid-19—is quite different than the one I describe in this chapter. The modes of seeing and being seen in these discourses are probably quite different for these health crises, and they deserve equal attention. Future scholarship will help nuance, rebuke, or clarify the claims I make.18

To foreground the broader cultures around tuberculosis, I am going to follow three case studies—on the sanatorium (1.2.1), hygiene (1.3.1), and the medical practitioner at work (1.4.1)—to define some ideological through-lines which will reappear in the next chapter (2.0.0). In doing this, my hope is to articulate in clear detail the eugenicist and capitalistic ideas which were reified in the process of fighting the disease (1.2.4; 1.3.5). Concepts of class, ability, cleanliness, and health appear in relation to the cultural conception of tuberculosis, as well as the popular and scientific understandings regarding treatment. As Linda Bryder has argued, tuberculosis doctors in the early twentieth century “showed themselves to be very much a product of the middle-class society from which they came, with its fixed assumptions about the poor.”19 This chapter extends this claim to think about how discourses around the disease, made possible by medical professionals, patients, and the lay public, reinforced these structures. By examining the profusion of gazes which saw tuberculosis, patients with tuberculosis, the sanitarium, and the doctors themselves, this chapter expands and complicates medical vision beyond the clinical (1.1.2; 2.1.2).

-

Sontag, Susan. Illness as Metaphor and AIDS and Its Metaphors. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1990. 25. ↩

-

Kübler-Ross, Elisabeth. On Death & Dying: What the Dying Have to Teach Doctors, Nurses, Clergy & Their Own Families. New York: Scribner, 1969; Ariés, Philippe. Western Attitude toward Death: From the Middle Ages to the Present. Translated by Patricia M. Ranum. Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1975; Saunders, Cicely, and Mary Baines. Living with Dying: The Management of Terminal Disease. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1983. ↩

-

Having returned to Sontag’s essay after doing the main research for this dissertation, I do think that her work with tuberculosis eschews scientific knowledge and discourses around the disease, relying too heavily on arts-informed receptions of the condition. Sontag is overdependent on the popular representation of pulmonary tuberculosis and is either uninterested in the disease’s many different presentations (from Pott’s disease to meningeal tuberculosis) or is unaware of the varied conditions linked to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. ↩

-

The AIDS crisis also brought with it a cultural interest in tuberculosis with exceptional scholarship penned by Linda Bryder and Georgina Feldberg. Both of their books were written in the wake of this historical moment.

Bryder, Linda. Below the Magic Mountain: A Social History of Tuberculosis in Twentieth-Century Britain. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1988; Feldberg, Georgina D. Disease and Class: Tuberculosis and the Shaping of Modern North American Society. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1995. ↩

-

A colleague of mine has told a story of her late husband’s memories of his grandfather being isolated from the family because he had tuberculosis. ↩

-

Abel, Emily K. Tuberculosis & the Politics of Exclusion: A History of Public Health & Migration to Los Angeles. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2007. ↩

-

A note on spelling: The institutions in the period of inquiry spelled sanatorium many different ways—often spelling the word sanitarium. I have chosen to standardize the spelling “sanatorium”, but will use other spellings when using proper names. ↩

-

My use of social construction comes largely from science and technology studies arguments, which sought to undermine the political objectivity of scientific research.

Latour, Bruno, and Steve Woolgar. Laboratory Life: The Construction of Scientific Facts. 2nd ed. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1986; Knorr Cetina, Karin. Epistemic Cultures: How the Sciences Make Knowledge. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999; Hacking, Ian. The Social Construction of What. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2000; Shapin, Steven. Never Pure: Historical Studies of Science as If It Was Produced by People with Bodies, Situated in Time, Space, Culture, and Society, and Struggling for Credibility and Authority. Baltimore, Md: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010. ↩

-

Dubos, René, and Jean Dubos. The White Plague: Tuberculosis, Man, and Society. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1952; Bynum, Hellen. Spitting Blood: The History of Tuberculosis. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012; Daniel, Thomas M. Captain of Death: The Story of Tuberculosis. New York: University of Rochester Press, 1997. ↩

-

Keats is not the only author evoked. Helen Bynum uses George Orwell as an artist who succumbed to tuberculosis in her book Spitting Blood.*

Bynum, Hellen. Spitting Blood: The History of Tuberculosis. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012. ↩

-

A main subtext for these arguments were ones based on evolutionary theories, race science, and eugenics (1.3.5). ↩

-

Feldberg, Georgina D. Disease and Class: Tuberculosis and the Shaping of Modern North American Society. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1995. ↩

-

The development of antibiotic and chemotherapy approaches to Mycobaterium tuberculosis in the mid-twentieth century made the disease almost non-existent in the western world; however, tuberculosis came back into the public consciousness because of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, as well as the emergence of antibiotic resistant TB. (See footnote 4 in this subsection.) ↩

-

Waldby, Catherine. The Visible Human Project: Informatic Bodies and Posthuman Medicine. London & New York: Routledge, 2000; Dijck, José van. The Transparent Body: A Cultural Analysis of Medical Imaging. Seattle & London: University of Washington Press, 2005; Cartwright, Lisa. Screening the Body: Tracing Medicine’s Visual Culture. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1995. ↩

-

O’Connor, Erin. “Camera Medica.” History of Photography 23, no. 3 (1999): 232–44; Cartwright, Lisa. Screening the Body: Tracing Medicine’s Visual Culture. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1995. ↩

-

Specifically images not tagged with the epistemic tags like “Anatomical” “Pathological” or references to extraction like “Organ” (X.1.4). ↩

-

This obliquely follows the kinds of interventions made by media archaeology scholars, who look to entangled, contested, and sometimes unsuccessful technologies and practices to understand health (0.1.3).

Huhtamo, Erkki, and Jussi Parikka, eds. Media Archaeology: Approaches, Applications, and Implications. Berkeley, Los Angeles & London: University of California Press, 2011; Parikka, Jussi. What Is Media Archaeology? Cambridge: Polity, 2012. ↩

-

A good example of the broader discourses around health can be seen in the double issue of Camera Obscura on medicine and film edited by Paula A. Treichler and Lisa Cartwright.

See: Camera Obscura 10(1-2). 1992. ↩

-

Bryder, Linda. Below the Magic Mountain: A Social History of Tuberculosis in Twentieth-Century Britain. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1988. ↩