Introduction

Specimen Studies

0.1.1 | 0.1.2 | 0.1.3 | 0.1.4 | 0.1.5Methods

0.2.1 | 0.2.2The Structure of this Dissertation

0.3.1Tuberculosis' Visual Culture

Visual Practices in Medical Culture

1.1.1 | 1.1.2 | 1.1.3Seeing and Settling in the Sanatorium Movement

1.2.1 | 1.2.2 | 1.2.3 | 1.2.4 | 1.2.5Teaching Public Health

1.3.1 | 1.3.2 | 1.3.3 | 1.3.4 | 1.3.5Representing Doctors in Tuberculous Contexts

1.4.1 | 1.4.2Using Human Specimens in the Study of Tuberculosis

Seeing Disease in Methyl Violet

2.1.1 | 2.1.2 | 2.1.3 | 2.1.4Case Histories

2.2.1 | 2.2.2 | 2.2.3 | 2.2.4Visceral Processes

2.3.1 | 2.3.2Relation

2.4.1 | 2.4.2 | 2.4.3Arts-Based Inquiry

Introduction

3.1.1 | 3.1.2 | 3.1.3 | 3.1.4Terminal Imaginaries & Tuberculous Imaginaries

3.2.1 | 3.2.2 | 3.2.3 | 3.2.4 | 3.2.5 | 3.2.6Dermographic Opacities

3.3.1 | 3.3.2 | 3.3.3 | 3.3.4Tactical Pretensions

3.4.1 | 3.4.2 | 3.4.3Designing Opacity

A Shift towards the Anticolonial

4.1.1 | 4.1.2 | 4.1.3 | 4.1.4Refusals and Opacities

4.2.1 | 4.2.2 | 4.2.3 | 4.2.4Digital and Ethical Workflows

4.3.1 | 4.3.2 | 4.3.3 | 4.3.4 | 4.3.5Conclusion

4.4.1Coda

Prometheus Undone

5.1.1 | 5.1.2 | 5.1.3 | 5.1.4Appendix

The Tuberculosis Corpus

X.1.1 | X.1.2 | X.1.3Web Design

X.2.1 | X.2.2 | X.2.3 | X.2.4Installation Materials

X.3.1 | X.3.2 | X.3.3Index

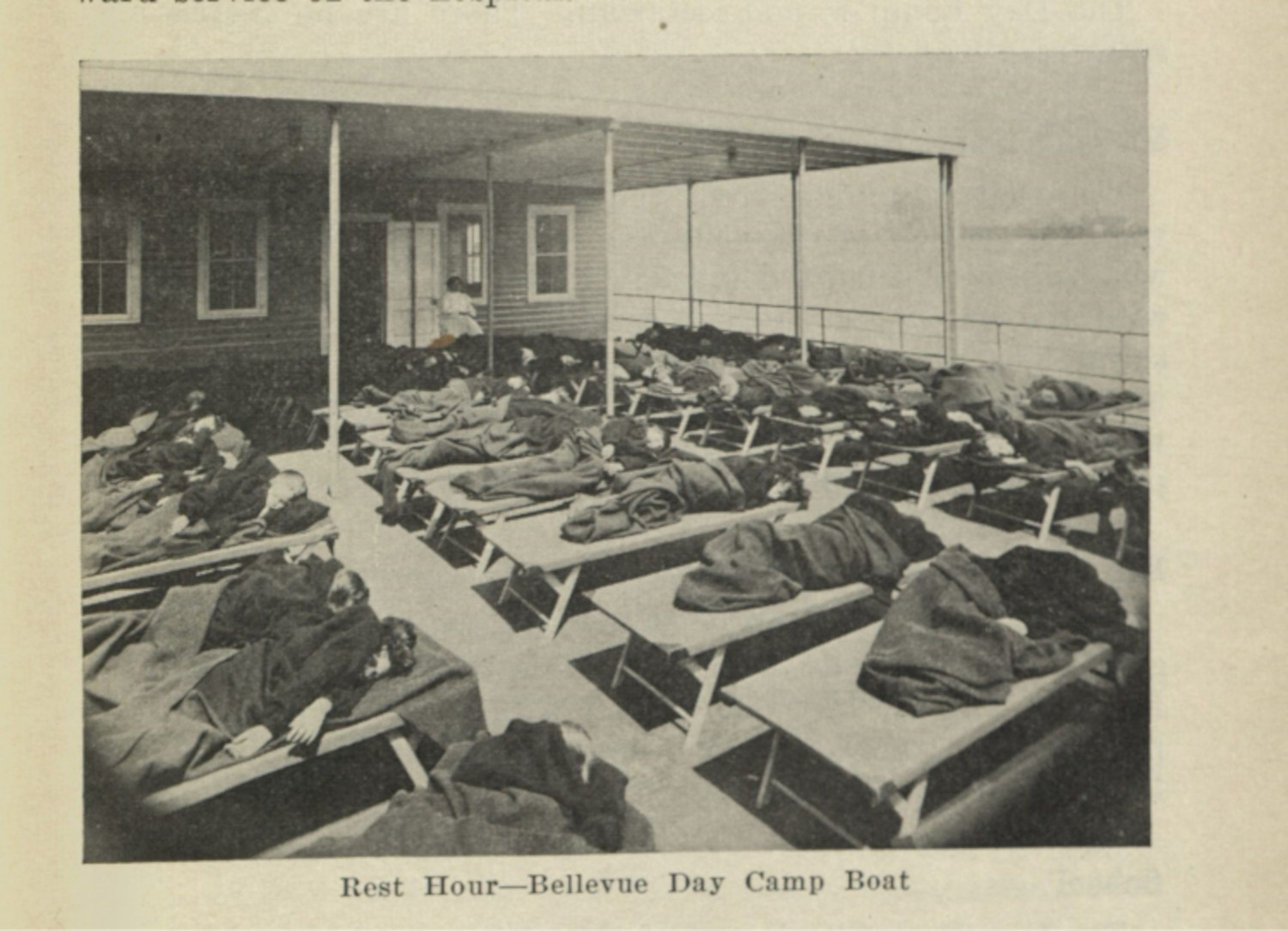

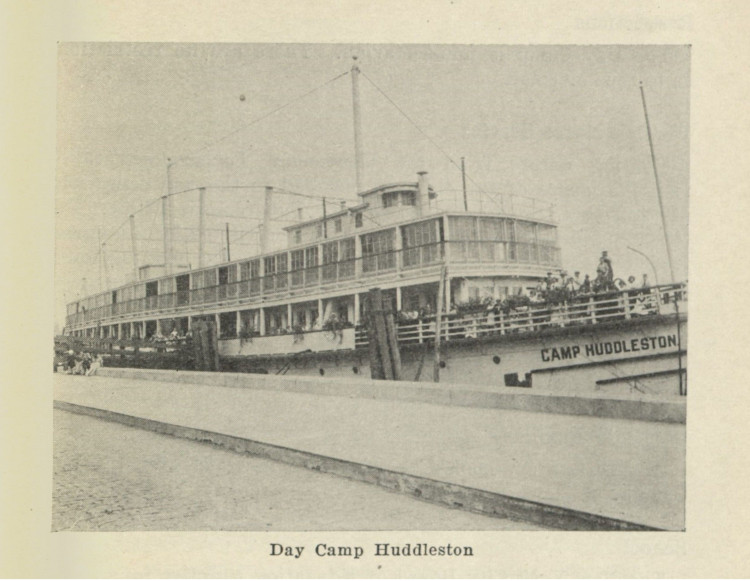

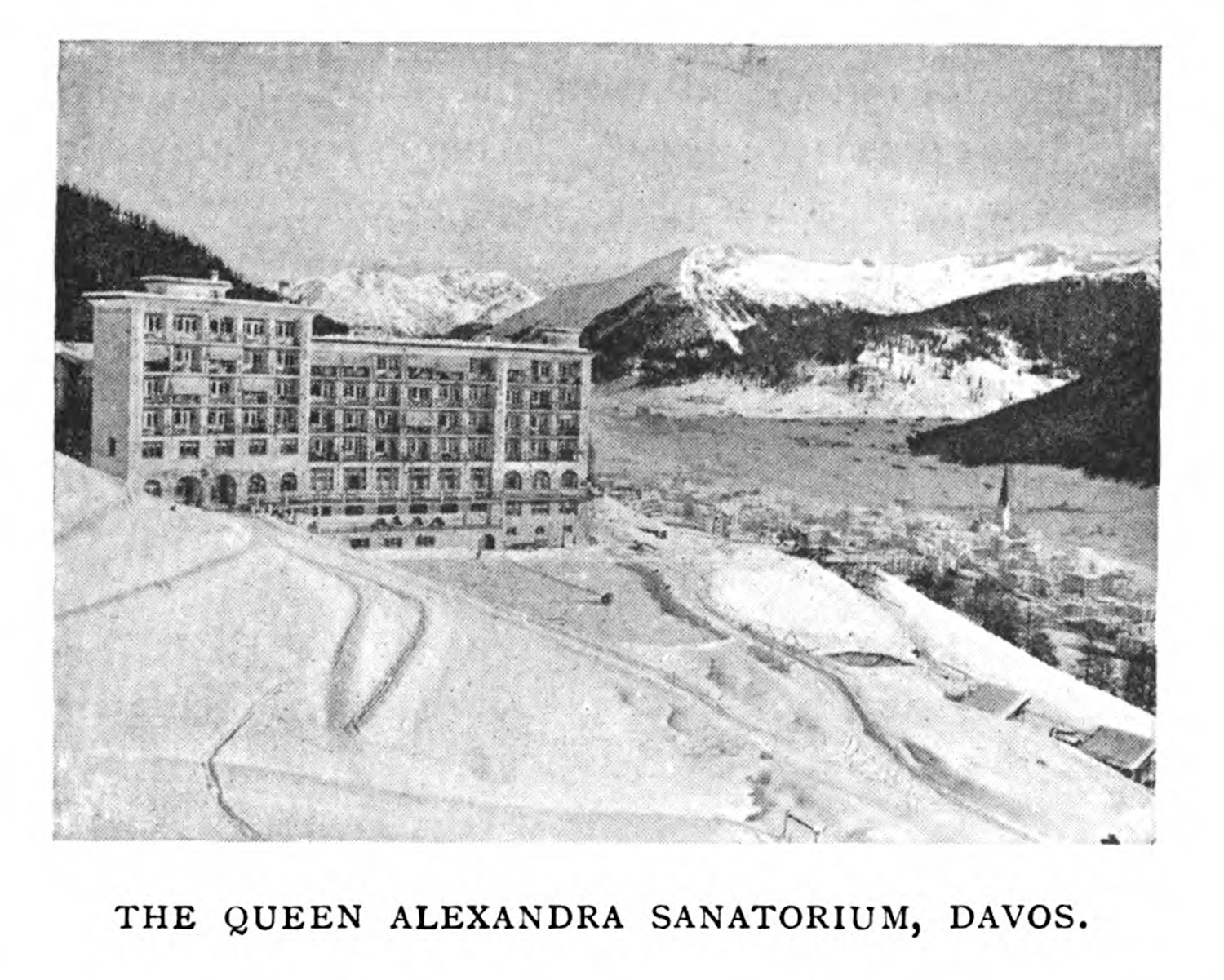

The sanatorium was a prominent, but not singular, actor in the medical intervention against tuberculosis. Hospitals, dispensaries, and day camps (figs. 1 & 2) also played pivotal roles during this period, by both treating and educating patients with tuberculosis (1.3.2). The sanatorium, however, had a central place in the public imagination of tuberculosis and medical interventions against the disease, owing in part to the number of institutions which treated patients in the early twentieth century, the Romantic ideology of retreat into nature, and its centrality in prominent literature—most importantly Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain, which depicted sanatorium treatment at Davos, Switzerland (fig. 3 & 4).1

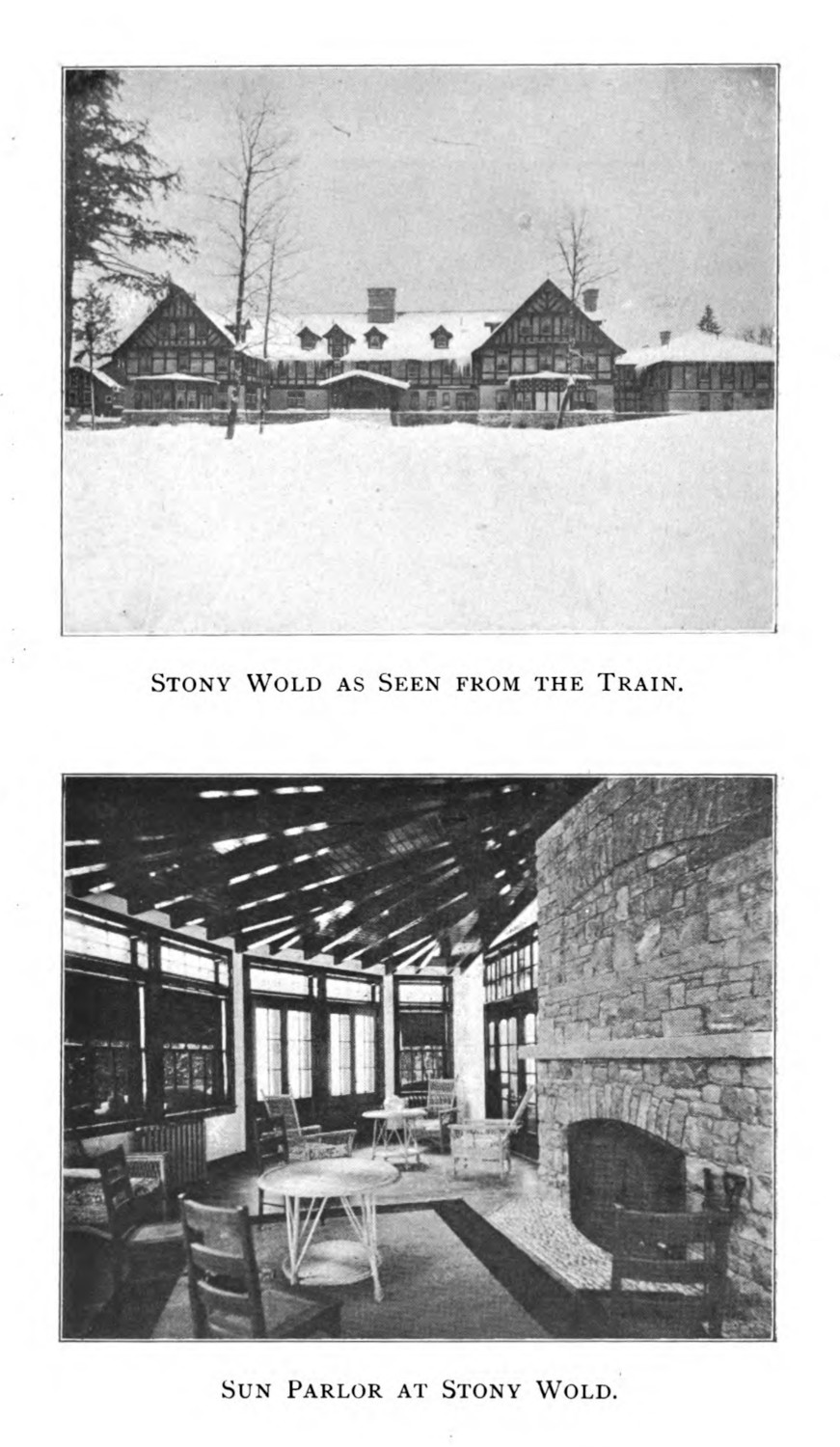

Sanatorium treatment usually involved a retreat from the urban. Patients had to travel to an institution located in some secluded space—Davos, Switzerland; the Adirondacks; the Rocky Mountains; Monrovia, California—which promised healing airs, the space for a rest cure, or the regimen of the working cure.2 These spaces often bordered the wilderness, promising an engagement with the outdoors and the contemplation of nature. Consumptive patients were encouraged to engage with the natural in an Emersonian way, where the wild and un-human space served as a place of emotional and spiritual communion. As Ralph Waldo Emerson writes in Nature,

In the woods too, a man casts off his years, as the snake his slough, and at what period soever of life, is always a child. In the woods, is perpetual youth. Within these plantations of God, a decorum and sanctity reign, a perennial festival is dressed, and the guest sees not how he should tire of them in a thousand years. In the woods, we return to reason and faith. There I feel that nothing can befall me in life,—no disgrace, no calamity, (leaving me my eyes,) which nature cannot repair. Standing on the bare ground,—my head bathed by the blithe air, and uplifted into infinite space,—all mean egotism vanishes. I become a transparent eye-ball; I am nothing; I see all; the currents of the Universal Being circulate through me; I am part or particle of God.3

In this section from Emerson’s longer philosophical treatise, being embedded in the natural—the pristine and untouched spaces void of human intervention—enabled a person’s connection to that space, affording a personal transcendence.

For E. L. Trudeau, an avid outdoorsman and hunter, it was his love of nature that brought him to the Adirondacks in the first place. The outdoors offered a space of reflection and regeneration (1.2.1):

Here the mountains, covered with an unbroken frost, rose so abruptly from the river, and the sweep of the valley at their base was so extended and picturesque, that the view had always made a deep impression upon me. Many a beautiful afternoon, for the first four winters after I came to Saranac Lake, I had sat for hours alone while hunting, facing the ever-changing phases of light and shade on the imposing mountain panorama at my feet, and dreamed the dreams of youth; dreamed of life and death and God, and yearned for a closer contact with the Great Spirit who planned it all, and for light on the hidden meaning of our troublous existence. The grandeur and peace of it had ever brought refreshment to my perplexed spirit.4

This connection to and engagement with the natural was likewise evoked in publications like The Journal of Outdoor Life. “The Naturalist”, a column that ran for two years in the magazine, displayed for patients with tuberculosis this contemplative, ecstatic engagement with the wild. In an example from an section describing the activities of woodpeckers, the author of the column writes:

The earliest ectasy (sic) is that of a musician playing on his chosen instrument rather than that of a songster: but the performance must be considered as a song. The downy woodpecker heralds the awakening of nature long before those harbingers of spring, the bluebird and robin return. I did not hear him till late in February, and even then his efforts were casual and intermittent: now his achievements pervade the stillness, particularly in the morning and evening.5

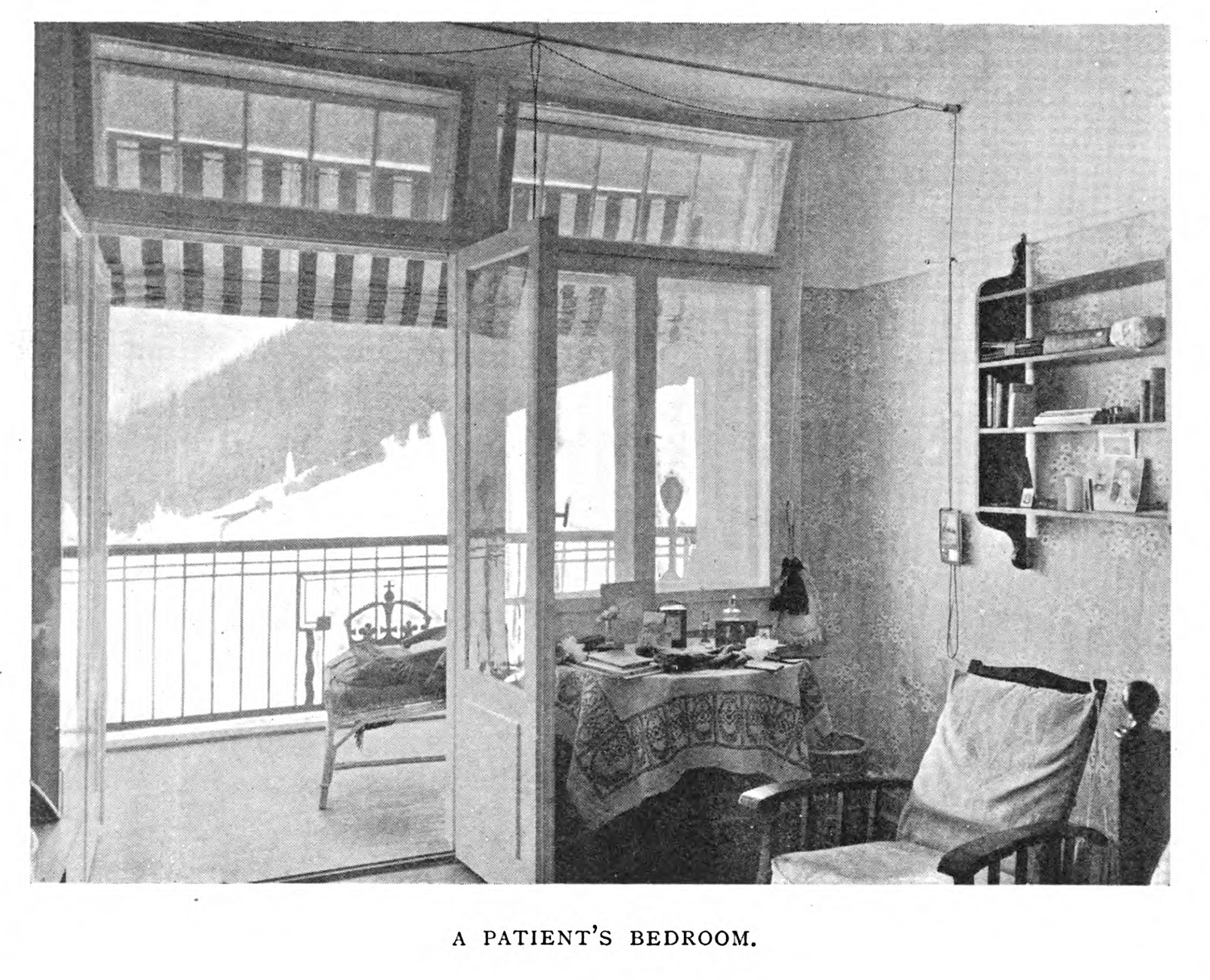

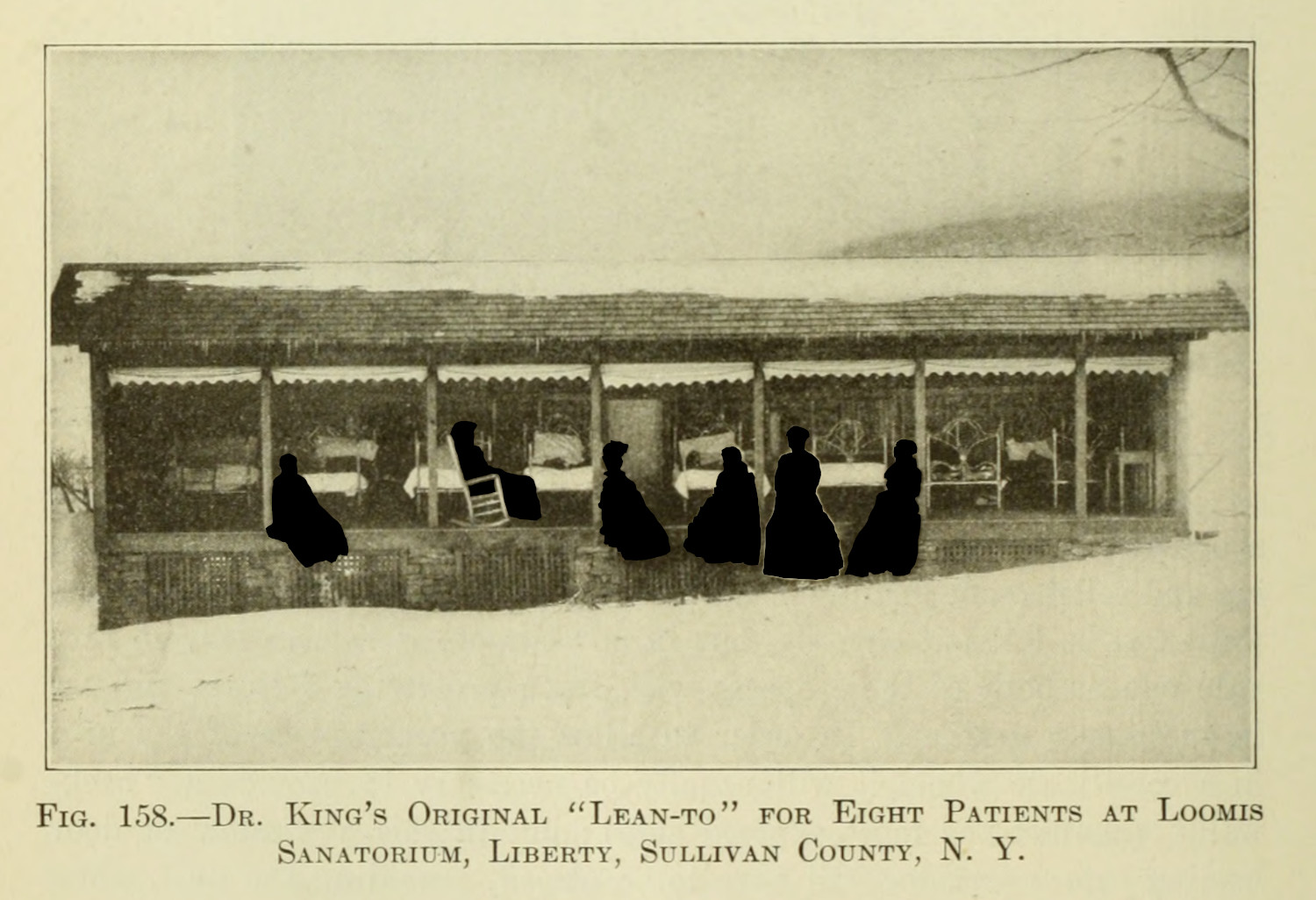

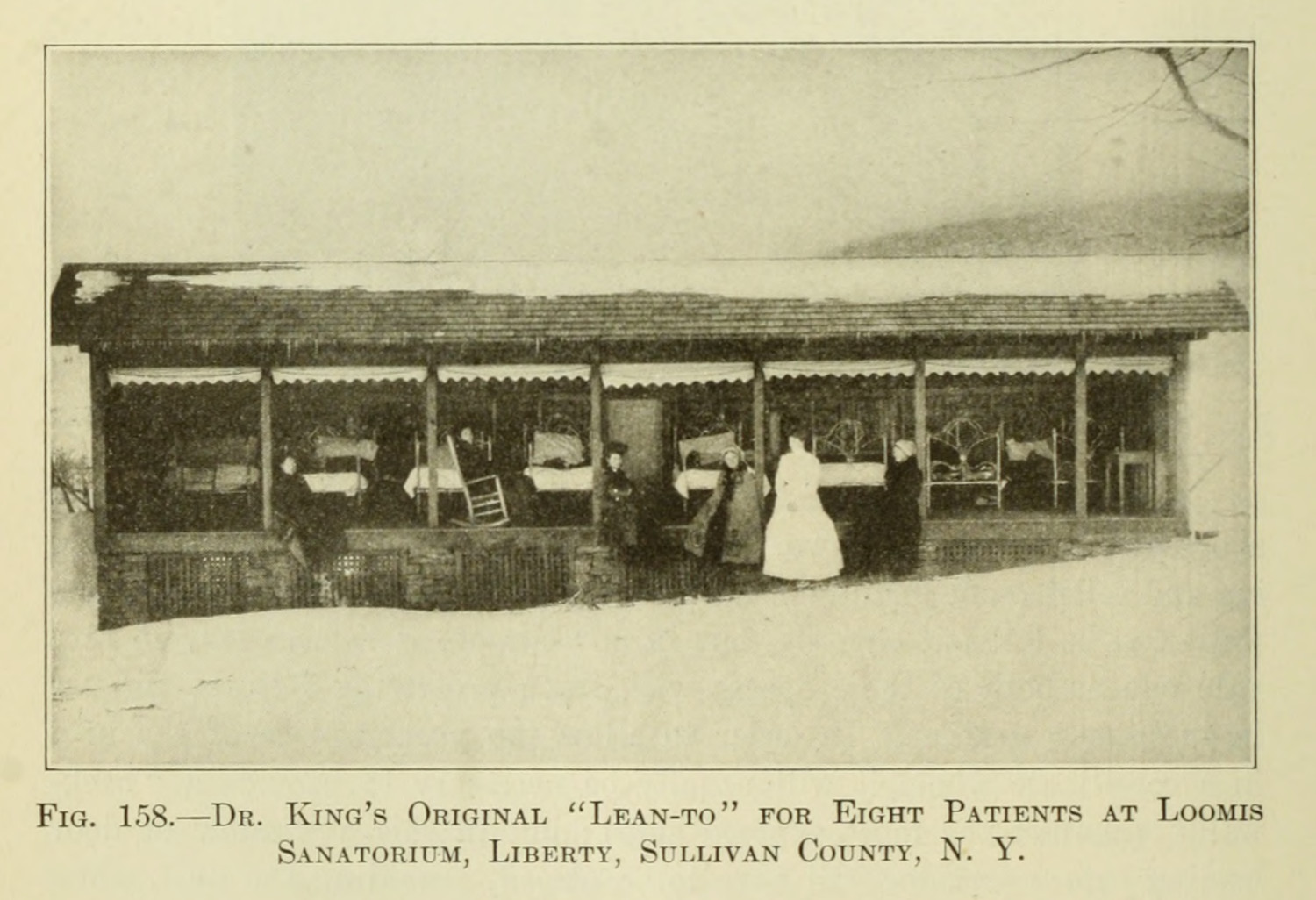

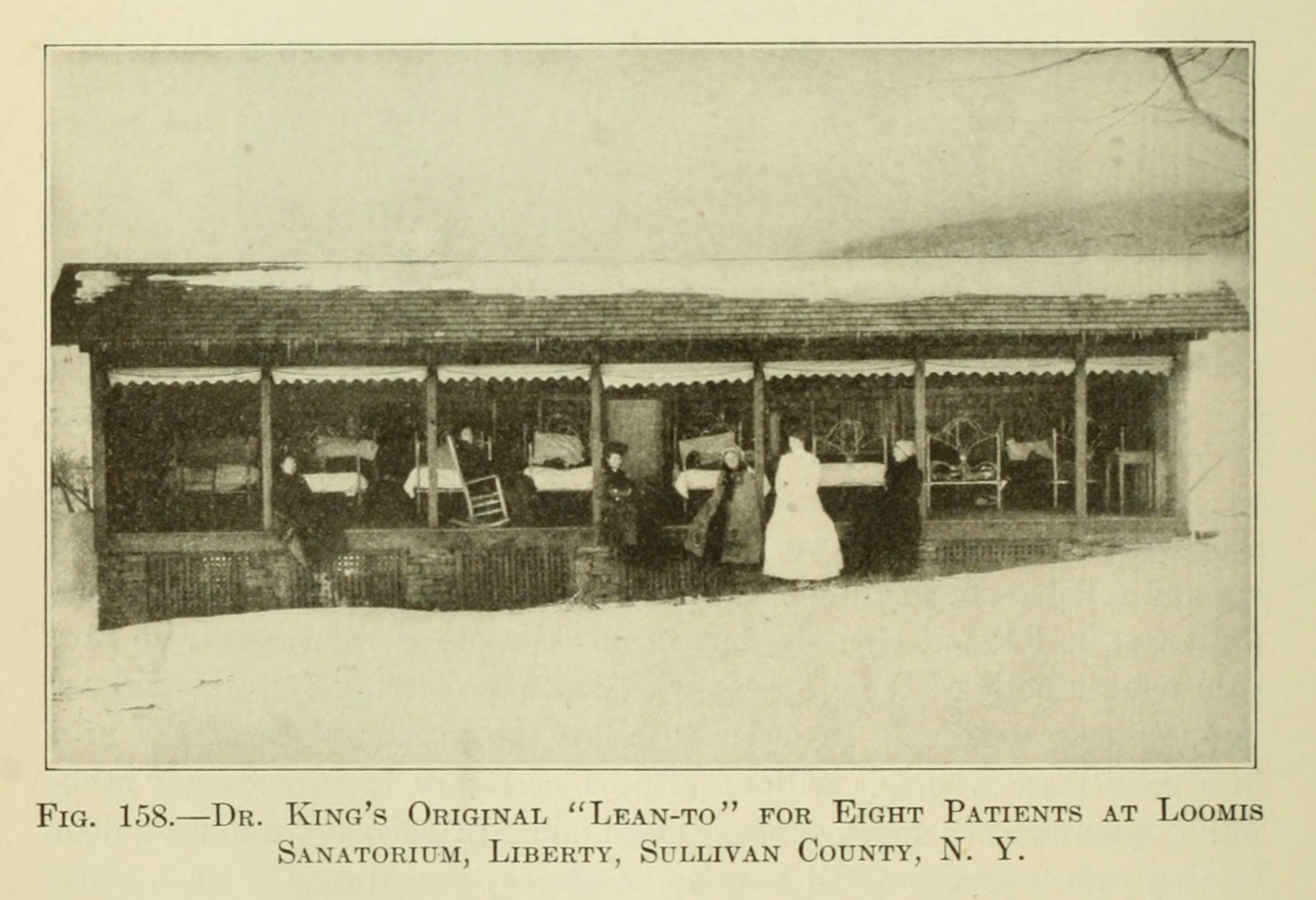

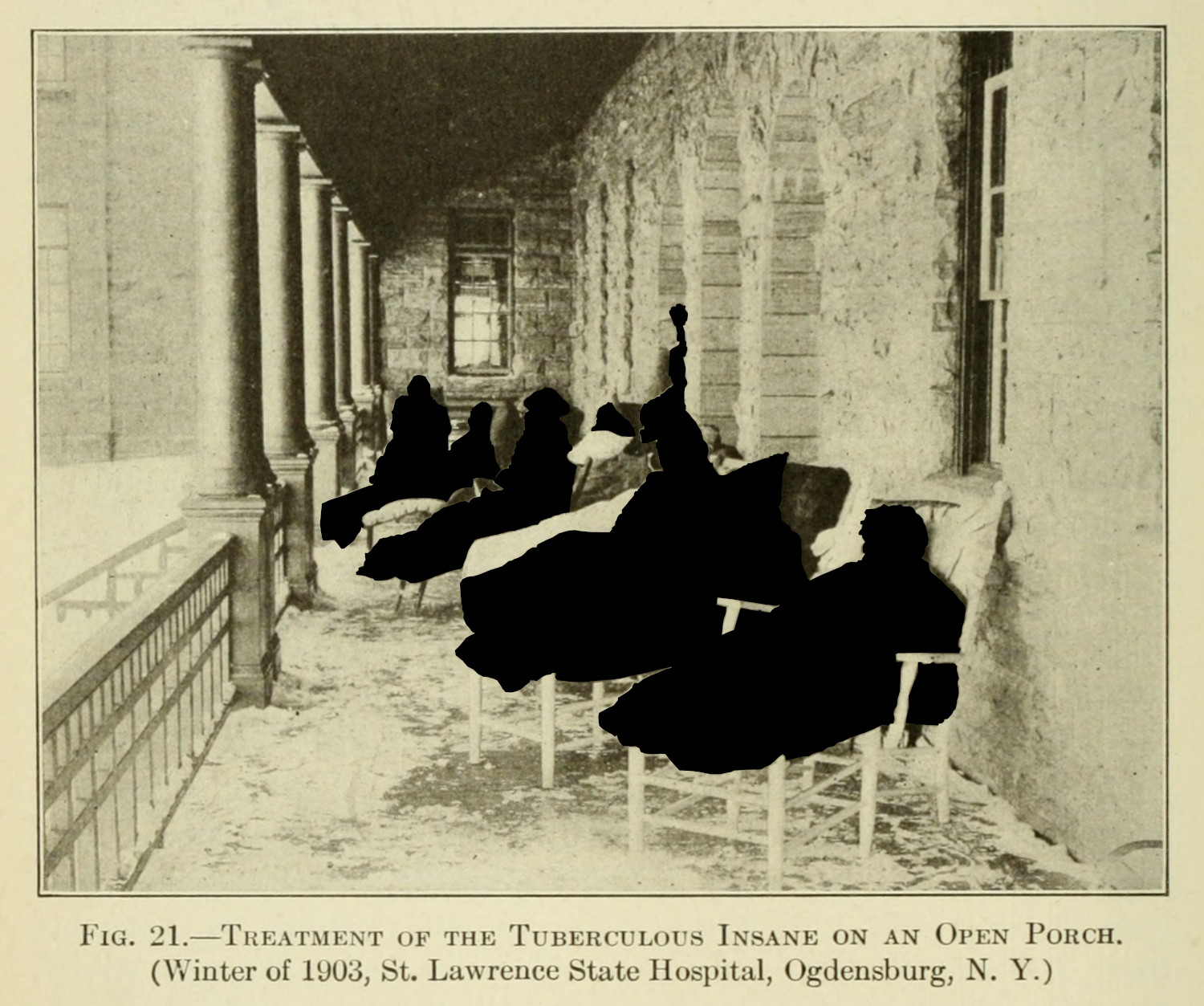

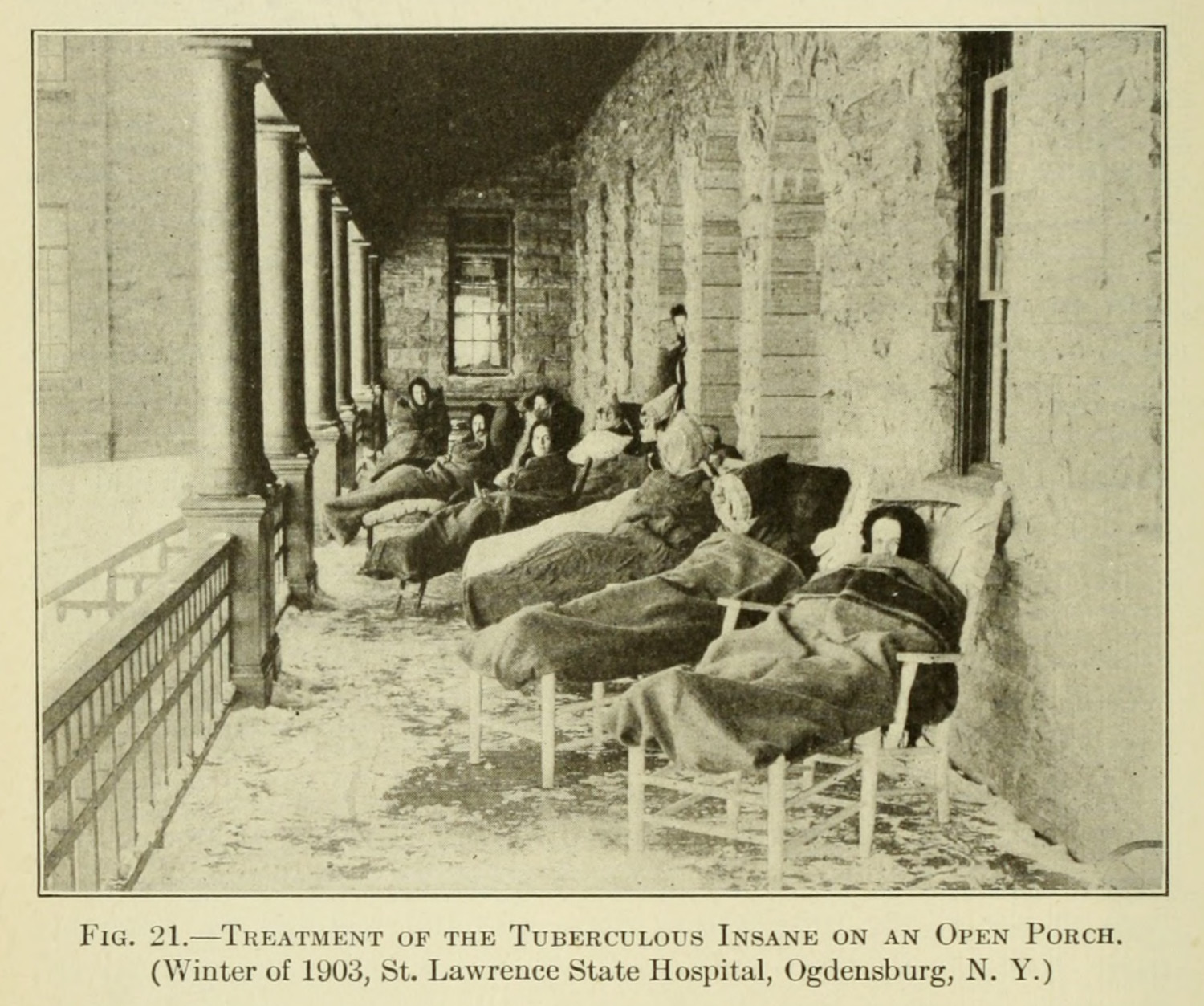

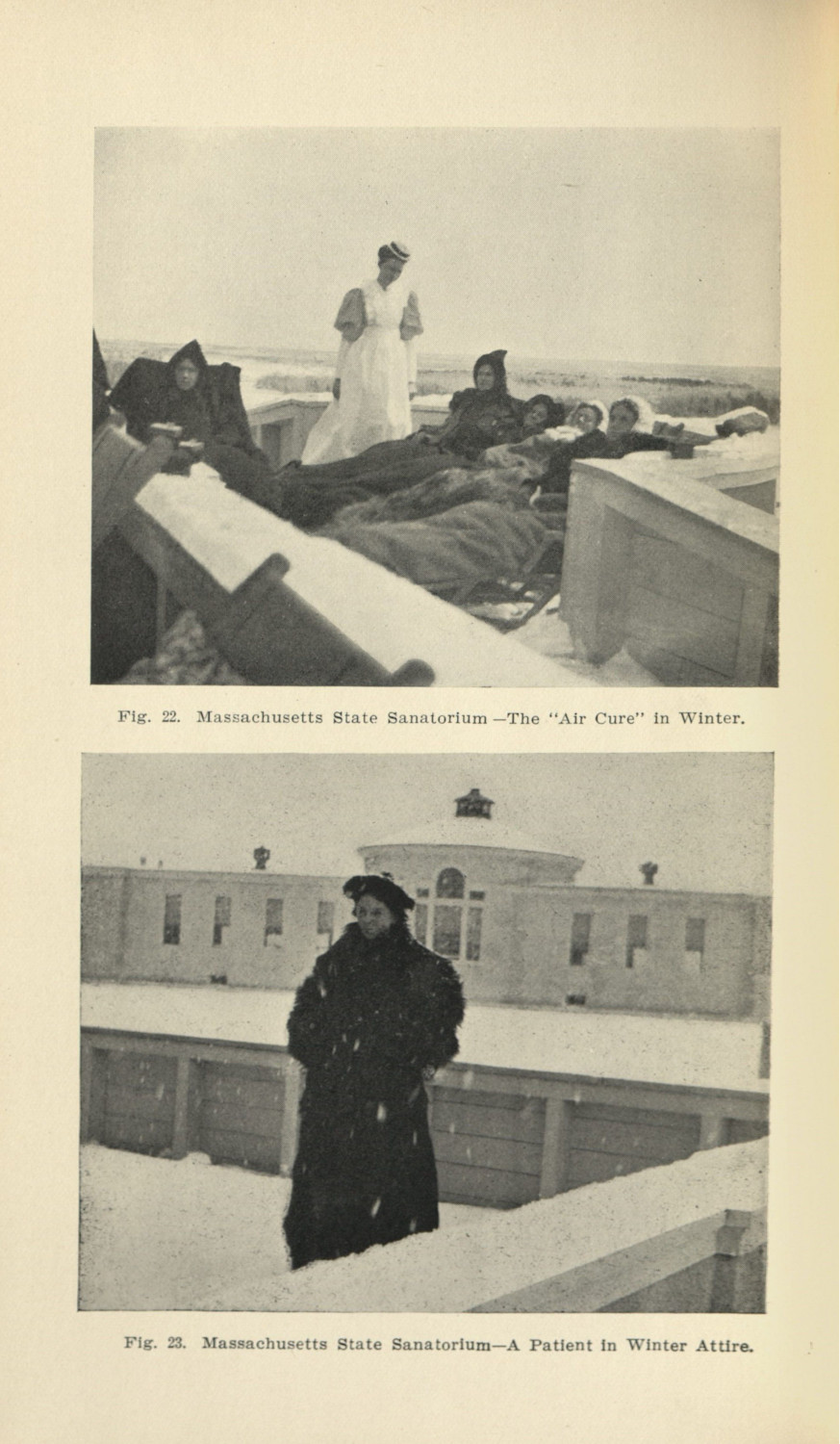

The sanatorium and the discourses around tuberculosis in America were tied to an escape from the urban, and with it a communion with the natural (1.3.2). In Emerson’s Nature it is the wilderness’ contrast with the city where the sharpest relief can be found. He writes, “In the wilderness, I find something more dear and connate than in streets or villages. In the tranquil landscape, and especially in the distant line of the horizon, man beholds somewhat as beautiful as his own nature.”6 The sanatorium represented separation from the urban, an evocation of the bounties of the untamed lands (fig. 5), the careful examination of the wilderness (fig. 6), and a mixture of exposure and shelter from the elements (fig. 7 & 10). This latter example was entangled with the practices of “open air treatment”—a therapy that required patients to be outside, or exposed to fresh air, for as many hours as possible each day (figs. 8 & 9).

-

There is much written about this novel, as it is a significant text in modern German literature. This topic, however, is beyond the scope of the current project. ↩

-

The working cure was more prominently practiced in the United Kingdom, and the rest cure was more popular in North America. Bryder, Linda. Below the Magic Mountain: A Social History of Tuberculosis in Twentieth-Century Britain. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1988. ↩

-

Ralph Waldo Emerson. Nature. Virginia Commonwealth University. 1836. ↩

-

Trudeau, Edward Livingston. An Autobiography. Garden City & New York: Doubleday, Doran & Company, Inc., 1944. 165-66. ↩

-

William E. D. Scott. “The Naturalist” in The Journal of the Outdoor Life: The Anti-Tuberculosis Magazine 4(3). New York: Trudeau Sanatorium, 1907. 103. ↩

-

Ralph Waldo Emerson. Nature. Virginia Commonwealth University. 1836. ↩