Introduction

Specimen Studies

0.1.1 | 0.1.2 | 0.1.3 | 0.1.4 | 0.1.5Methods

0.2.1 | 0.2.2The Structure of this Dissertation

0.3.1Tuberculosis' Visual Culture

Visual Practices in Medical Culture

1.1.1 | 1.1.2 | 1.1.3Seeing and Settling in the Sanatorium Movement

1.2.1 | 1.2.2 | 1.2.3 | 1.2.4 | 1.2.5Teaching Public Health

1.3.1 | 1.3.2 | 1.3.3 | 1.3.4 | 1.3.5Representing Doctors in Tuberculous Contexts

1.4.1 | 1.4.2Using Human Specimens in the Study of Tuberculosis

Seeing Disease in Methyl Violet

2.1.1 | 2.1.2 | 2.1.3 | 2.1.4Case Histories

2.2.1 | 2.2.2 | 2.2.3 | 2.2.4Visceral Processes

2.3.1 | 2.3.2Relation

2.4.1 | 2.4.2 | 2.4.3Arts-Based Inquiry

Introduction

3.1.1 | 3.1.2 | 3.1.3 | 3.1.4Terminal Imaginaries & Tuberculous Imaginaries

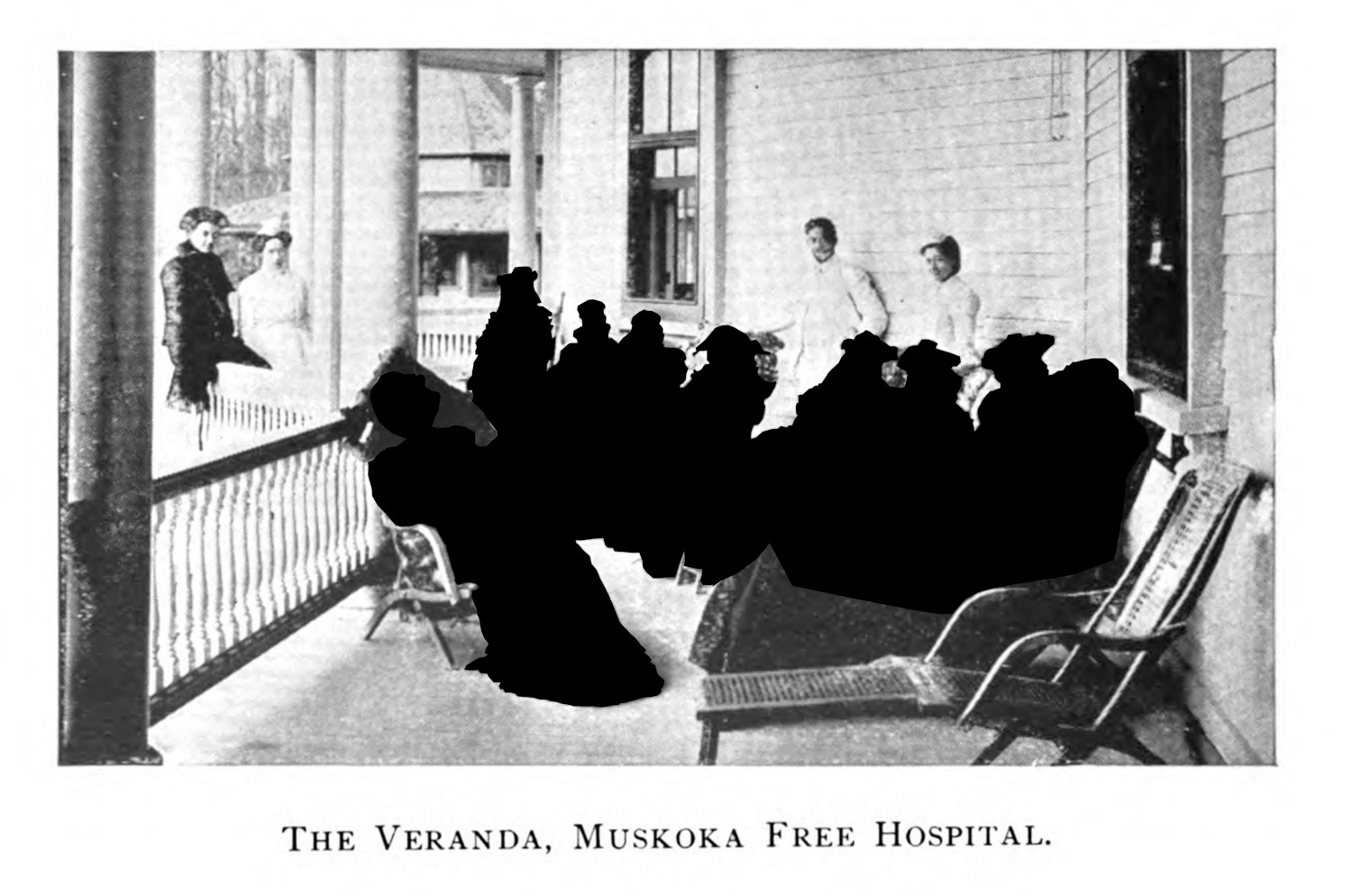

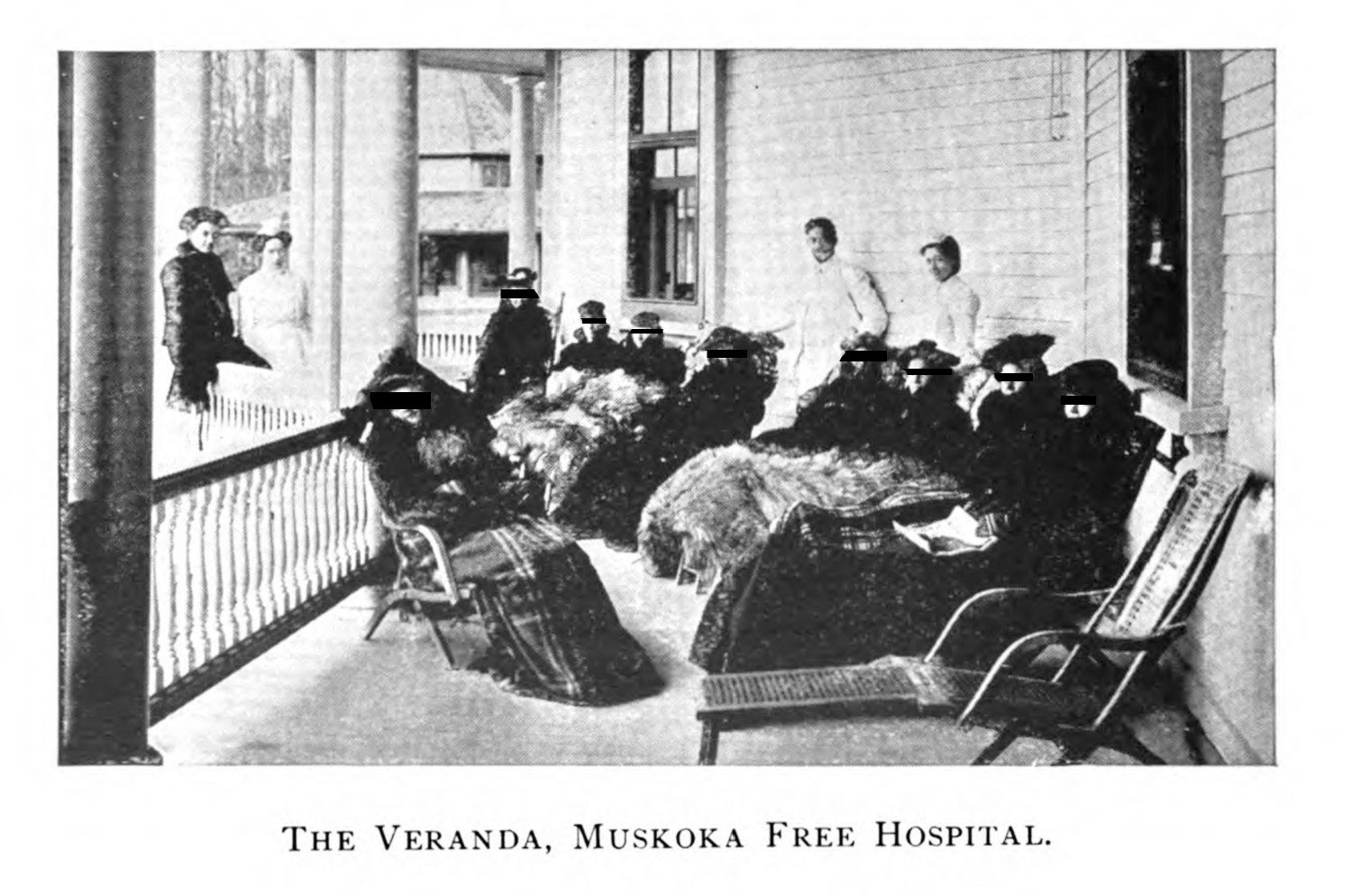

3.2.1 | 3.2.2 | 3.2.3 | 3.2.4 | 3.2.5 | 3.2.6Dermographic Opacities

3.3.1 | 3.3.2 | 3.3.3 | 3.3.4Tactical Pretensions

3.4.1 | 3.4.2 | 3.4.3Designing Opacity

A Shift towards the Anticolonial

4.1.1 | 4.1.2 | 4.1.3 | 4.1.4Refusals and Opacities

4.2.1 | 4.2.2 | 4.2.3 | 4.2.4Digital and Ethical Workflows

4.3.1 | 4.3.2 | 4.3.3 | 4.3.4 | 4.3.5Conclusion

4.4.1Coda

Prometheus Undone

5.1.1 | 5.1.2 | 5.1.3 | 5.1.4Appendix

The Tuberculosis Corpus

X.1.1 | X.1.2 | X.1.3Web Design

X.2.1 | X.2.2 | X.2.3 | X.2.4Installation Materials

X.3.1 | X.3.2 | X.3.3Index

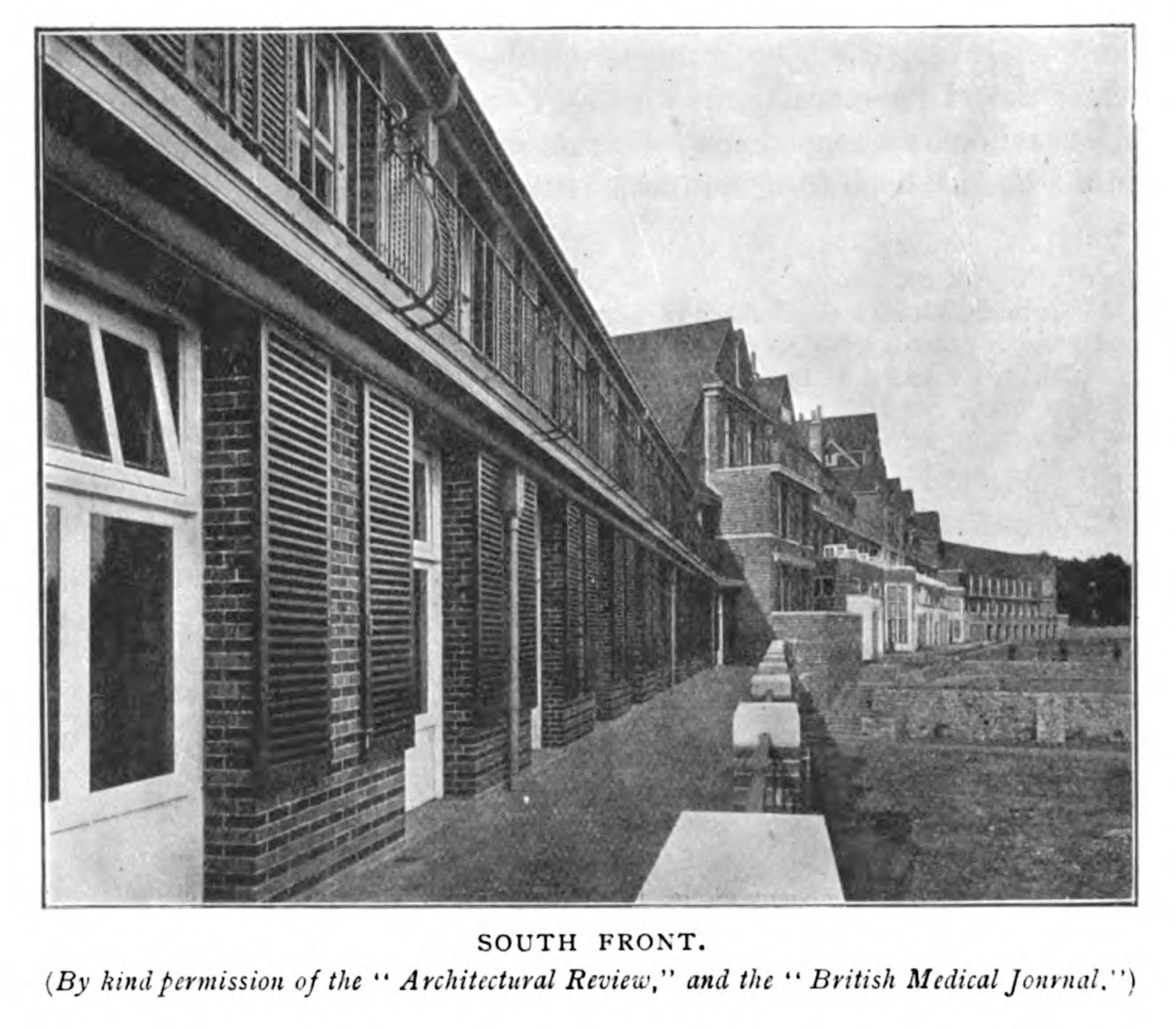

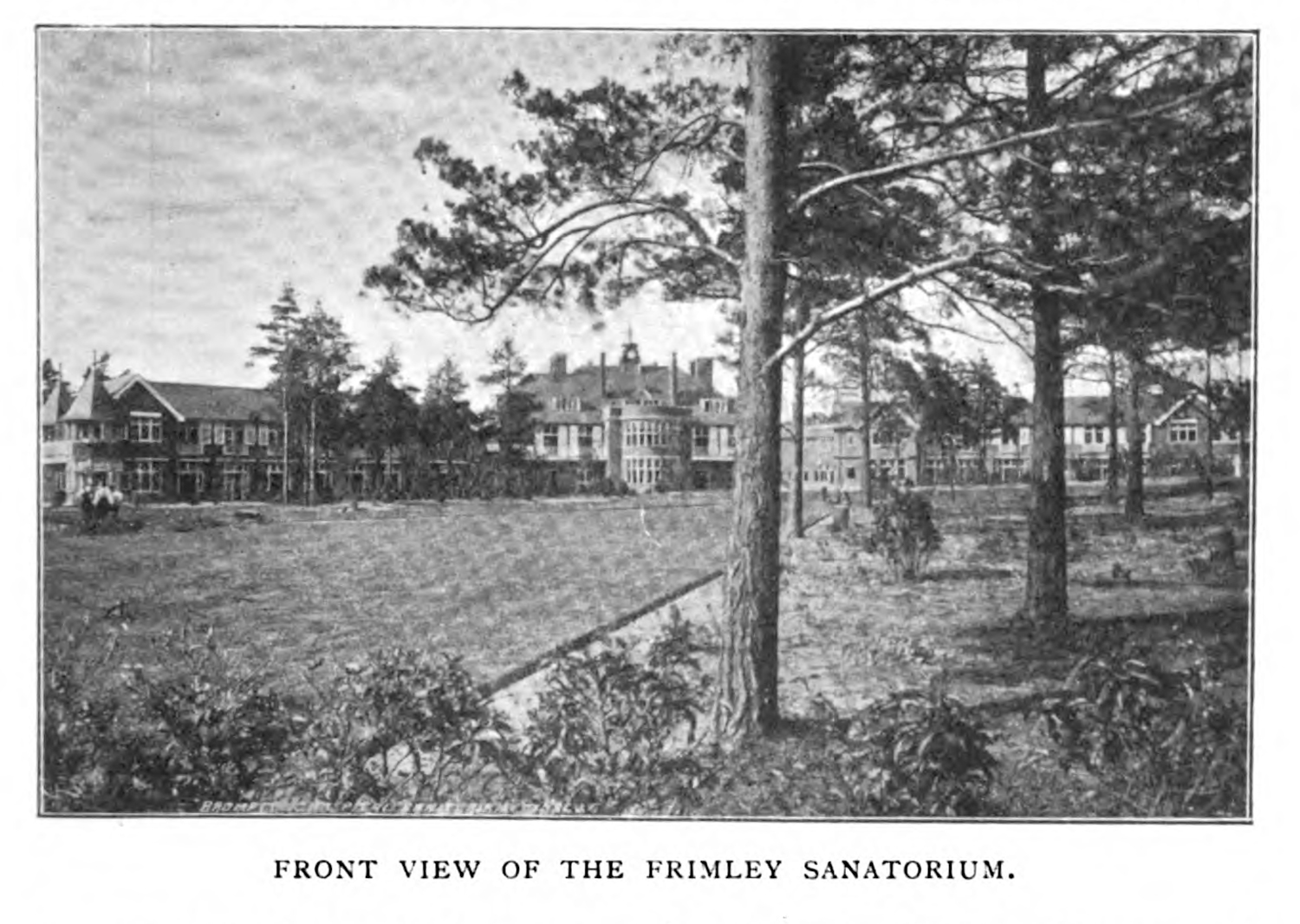

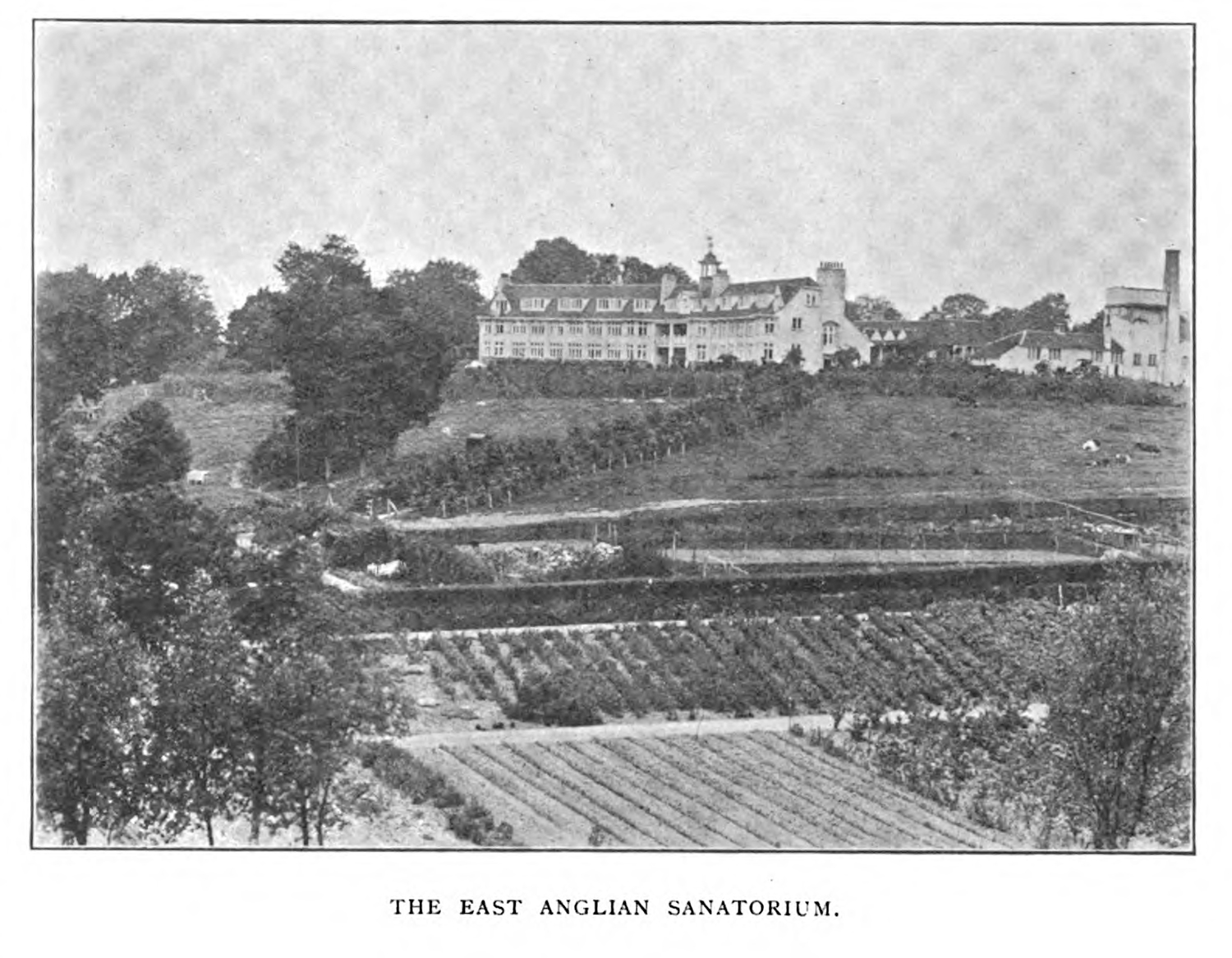

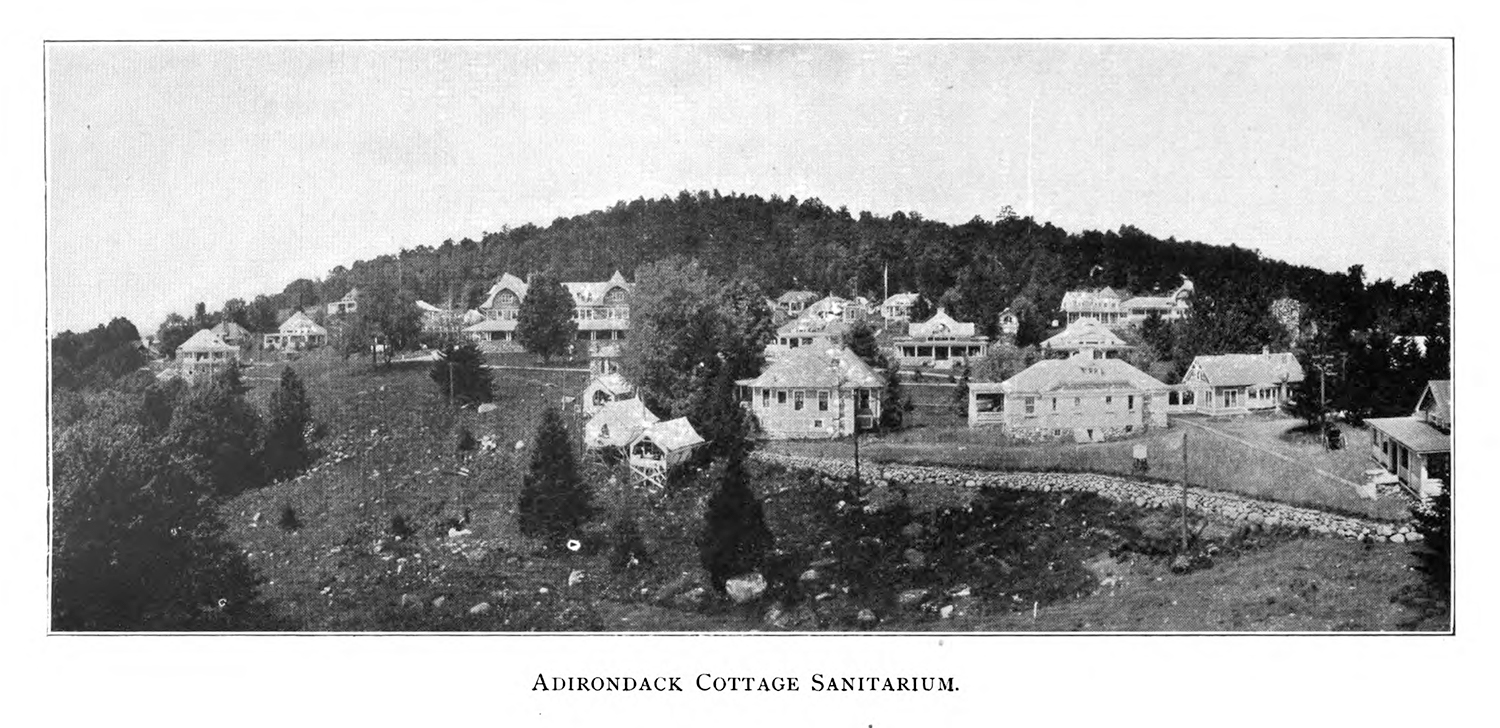

Trudeau’s Adirondack Cottage Sanitarium was a model in the United States (1.2.1), but it was not a monolith, as doctors oversaw different treatment regimens, from the open air treatment, to the rest cure, to the working cure. What unified many was the thought that patients could and should travel a great distance to receive treatment, and that the medical space that patients travelled to could be engineered in such a way as to be beneficial. The discussion of sanatoria, their architectural and therapeutic benefits, litter the tuberculosis corpus (X.1.1). The British Journal of Tuberculosis had a pair of long running series which promoted health institutions in the United Kingdom and Europe. “Institutions for the Tuberculous” spotlighted various health resorts and facilities, providing information about more local hospitals. The first issue of the first volume described the facilities of the King Edward VII Sanatorium in Midhurst (figs. 1 & 2), the Brompton Hospital Sanatorium and Convalescent Home in Frimley (fig. 3), and the East Anglian Sanatorium in Suffolk (fig. 4).

For the facilities described in “Institutions for the Tuberculous”, time was spent describing the amenities. The King Edward VII Sanatorium was described as having

2 hydropathic-rooms, 2 writing-rooms, 100 patients’ bedrooms (50 men and 50 women), with 6 nurses’ kitchens, linen-rooms, etc. The patients’ bedrooms measure 13 feet 6 inches by 11 feet 6 inches, and are 11 feet high. The large windows open out on a balcony 8 feet in width.1

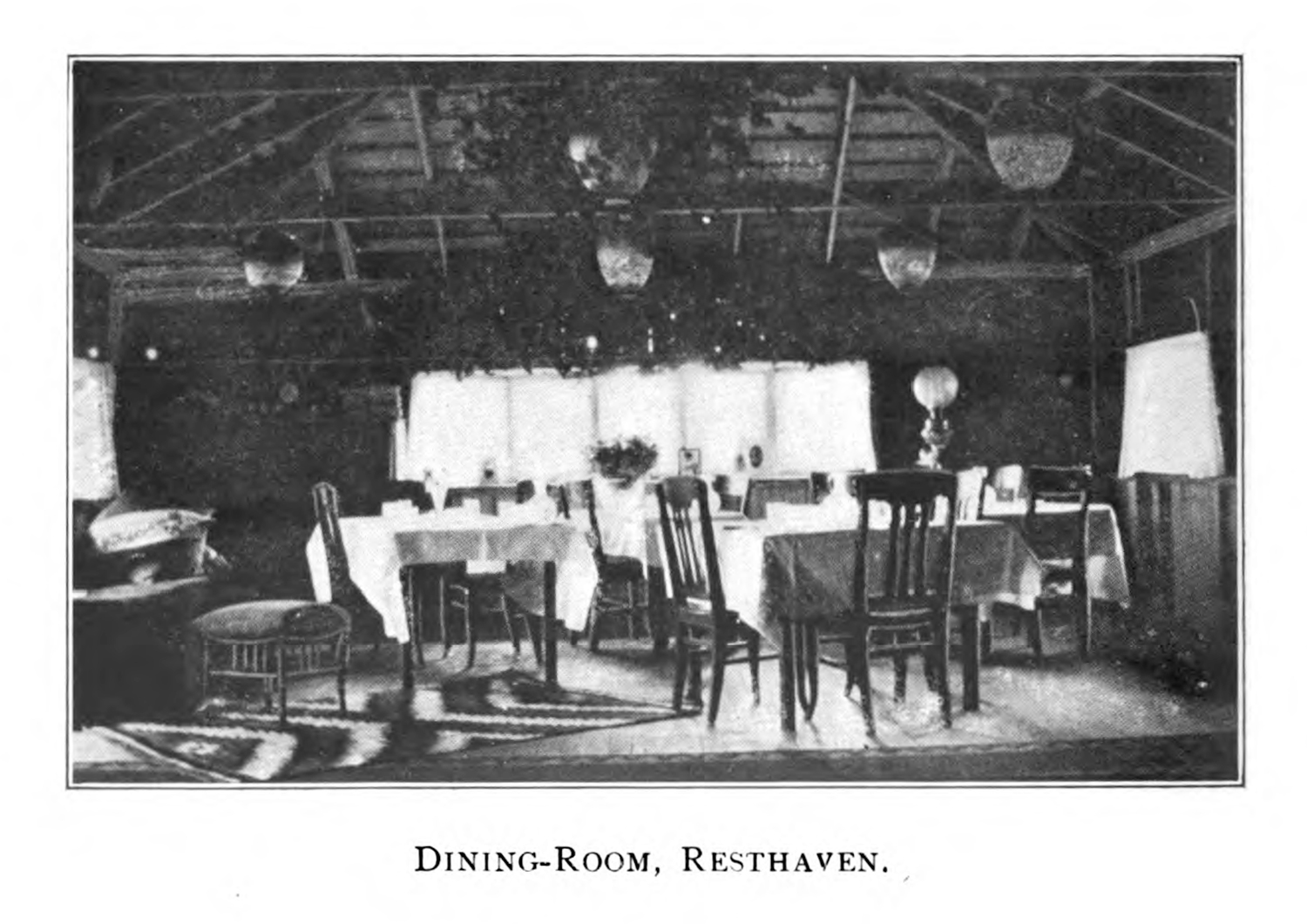

These more rote descriptions were matched with depictions of the dining halls and research facilities. Dining spaces were represented as richly appointed, the costliness of furnishings as important features that provided physical comfort: “The dining hall is a handsome room, lined with Doulton Carrera ware, the floor being of stone, which can be heated from beneath.”2 Research facilities were described in similarly rich terms, but to different effect: “The pathological block consists of a post-mortem-room and thee well-appointed rooms for pathological and research work. Researches [sic] which have a direct bearing upon the treatment of consumption will form an important feature of this department.”3 In a journal that aims toward an academic, scientific audience, the space was both a curative agent and signifier of its high class, comfortable status. The King Edward VII Sanatorium presented itself in such a way because it was unlike other institutions. As Vincent Y. Bowditch states in a puff piece on British sanatoria for The Journal of Outdoor Life, “the sanatorium is not a charitable institution in the strict sense of the word, it being the wish of King Edward that wealthy patients should be accommodated as well as other less well-to-do people.”4 With rooms running as much as five guineas (or around $26) a week5 and costing as little as two pounds two shillings (or around $10.50) for a week of care,6 the sanatorium was hoping to serve middle to upper class patients.7 The luxurious framing helped sell the sanatorium and its costly treatments to the journal’s audience—doctors and medical practitioners—and convince them that the well appointed institution might benefit their patients with tuberculosis. With its brief descriptions of the amenities, the entries for “Institutions for the Tuberculous” read as ways for the professional practitioners to learn about potential facilities to which they could send their patients.

It was also likely that patients who were sick with the disease, or families of those who were sick, would look to the quasi-advertisements of sanatoria published in medical journals, or in collected books of sanatoria like the Hand Book of Help for Persons Suffering from Pulmonary Tuberculosis (Consumption) Directory of Tuberculosis Hospitals Sanatoria and Clinics published in 1915 by New York City’s Department of Health or Lilian Brandt’s 1904 book A Directory of Institutions and Societies Dealing with Tuberculosis in the United States and Canada. In the introduction to the latter monograph, Brandt says that the book was “designed, first, to serve as a guide to the physicians and friends of consumptives, whether poor or well-to-do, by furnishing accurate information in regard to existing institutions”.8 Many of the images in the corpus come from these kinds of publications, which were unscientific or quasi-scientific but spoke to an audience made up in part of practicing doctors, and in part by people with tuberculosis or their loved ones.

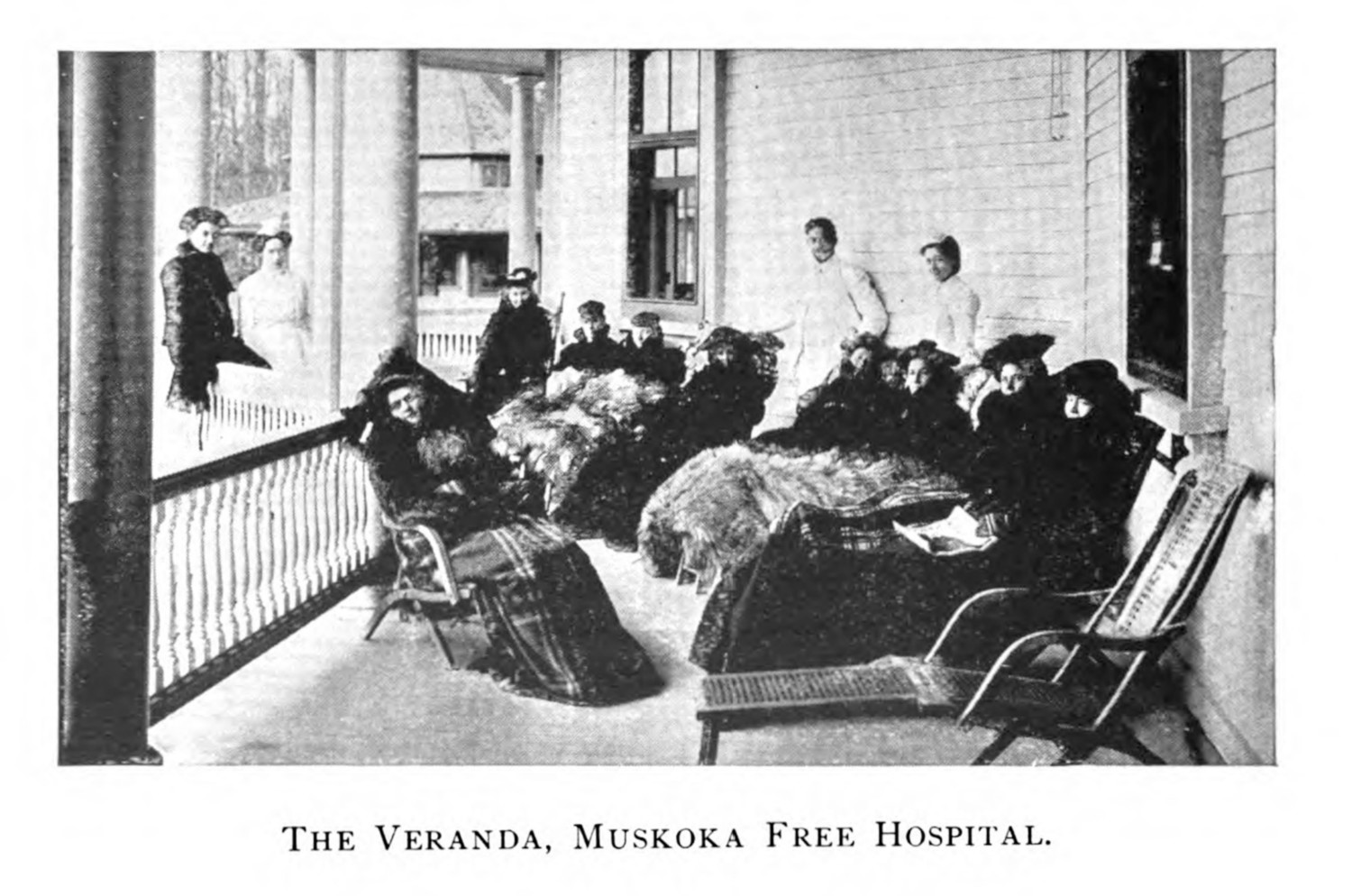

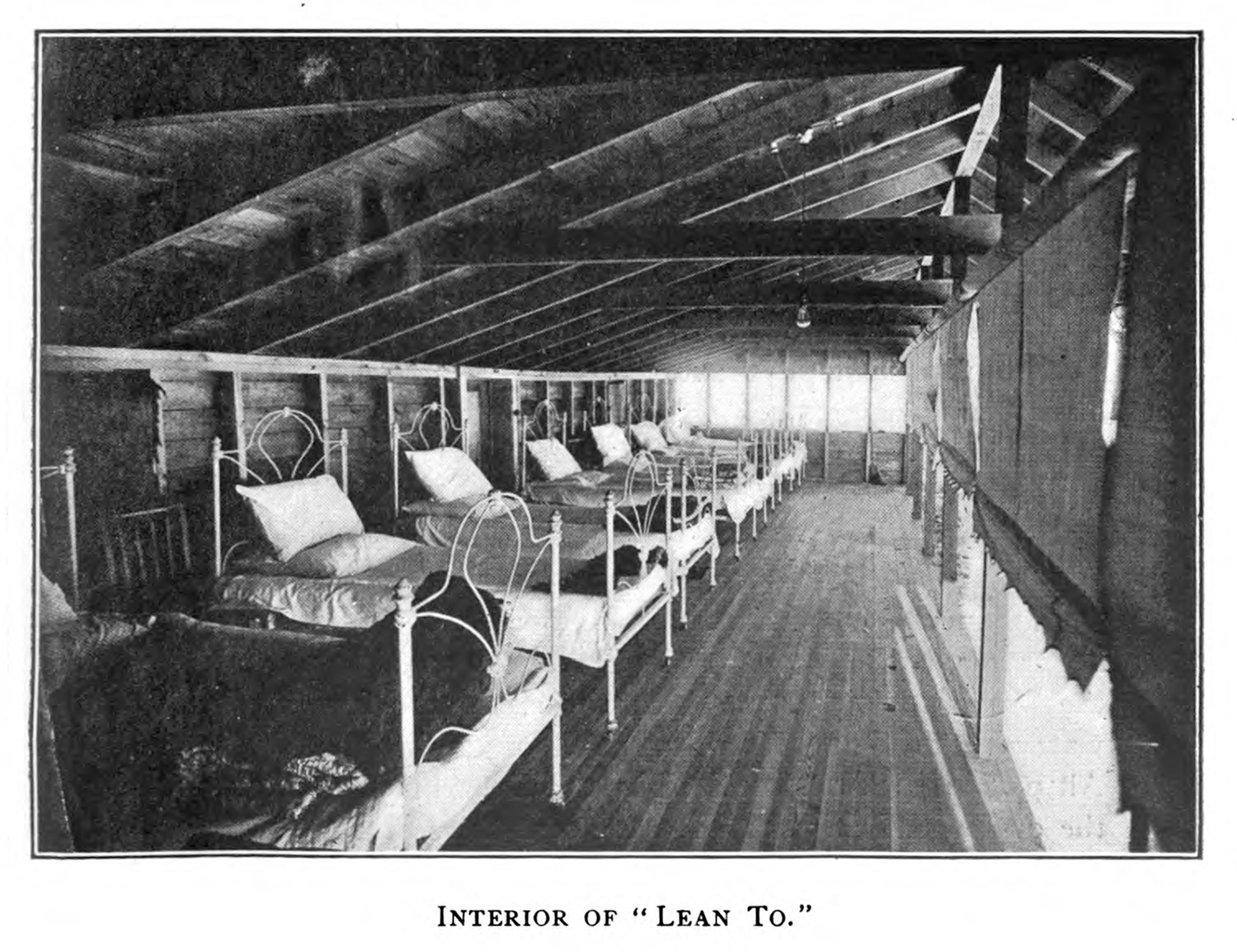

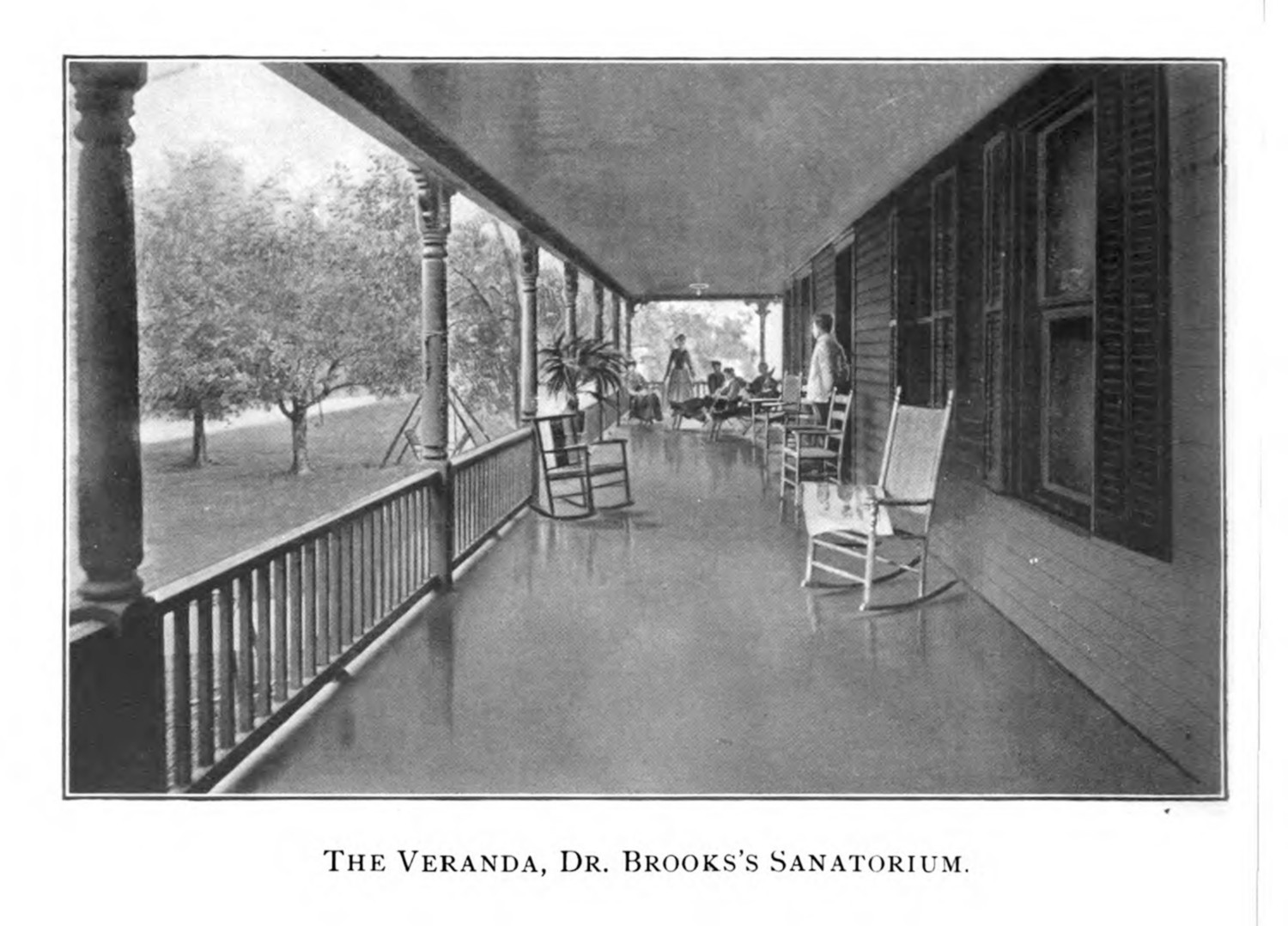

Brandt’s directory, like The British Journal of Tuberculosis, used photographs to make its argument. There are images of buildings, nestled comfortably in the landscape (fig. 5), empty and sterile rooms for rest and socialization (figs. 7 & 8), and relatively few images that actually show patients (fig. 6). Some photos give the impression that the patients who are in the frame are left as an afterthought. They are incidental figures largely present to demonstrate the luxurious space of the sanatorium buildings (figs. 8 & 9).

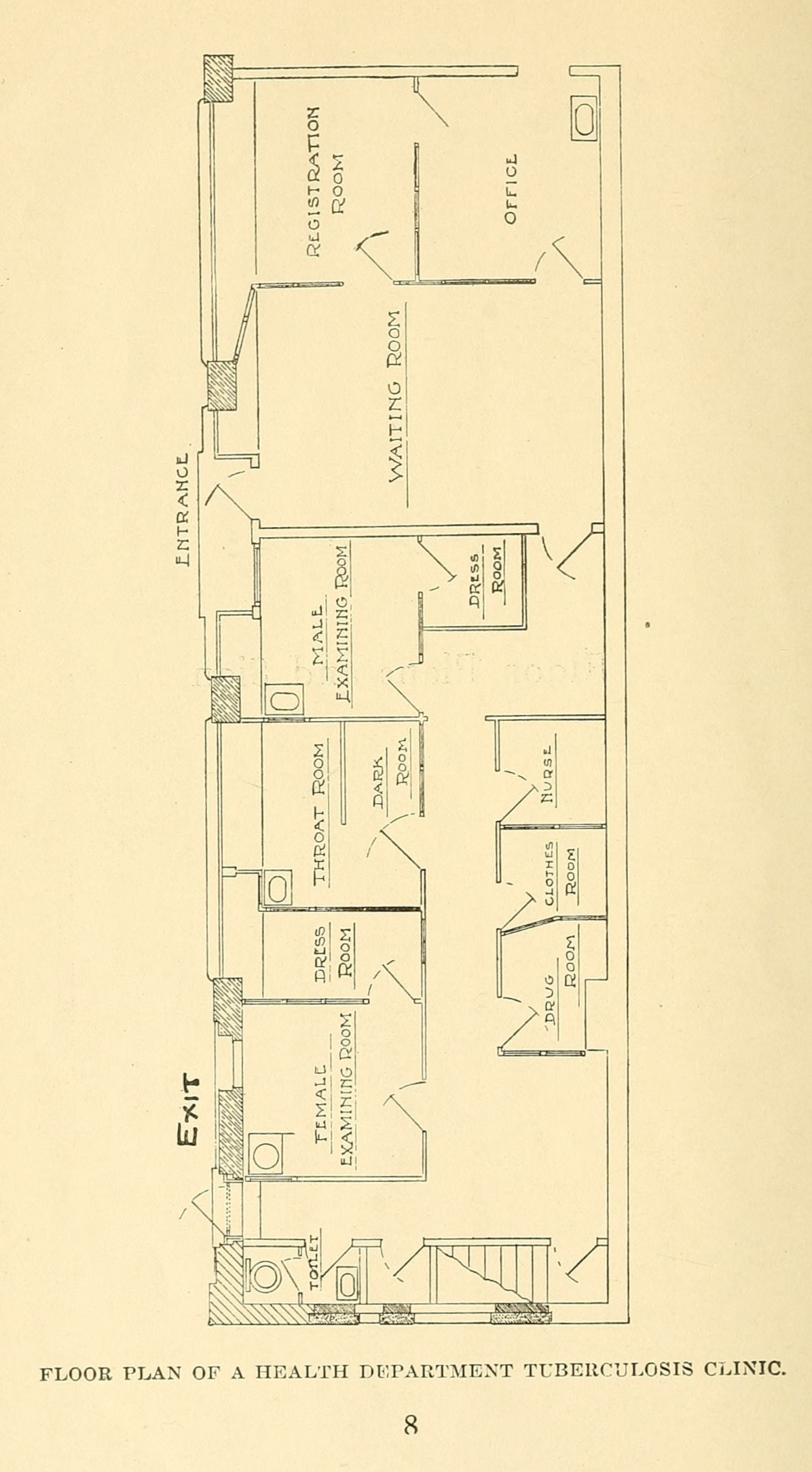

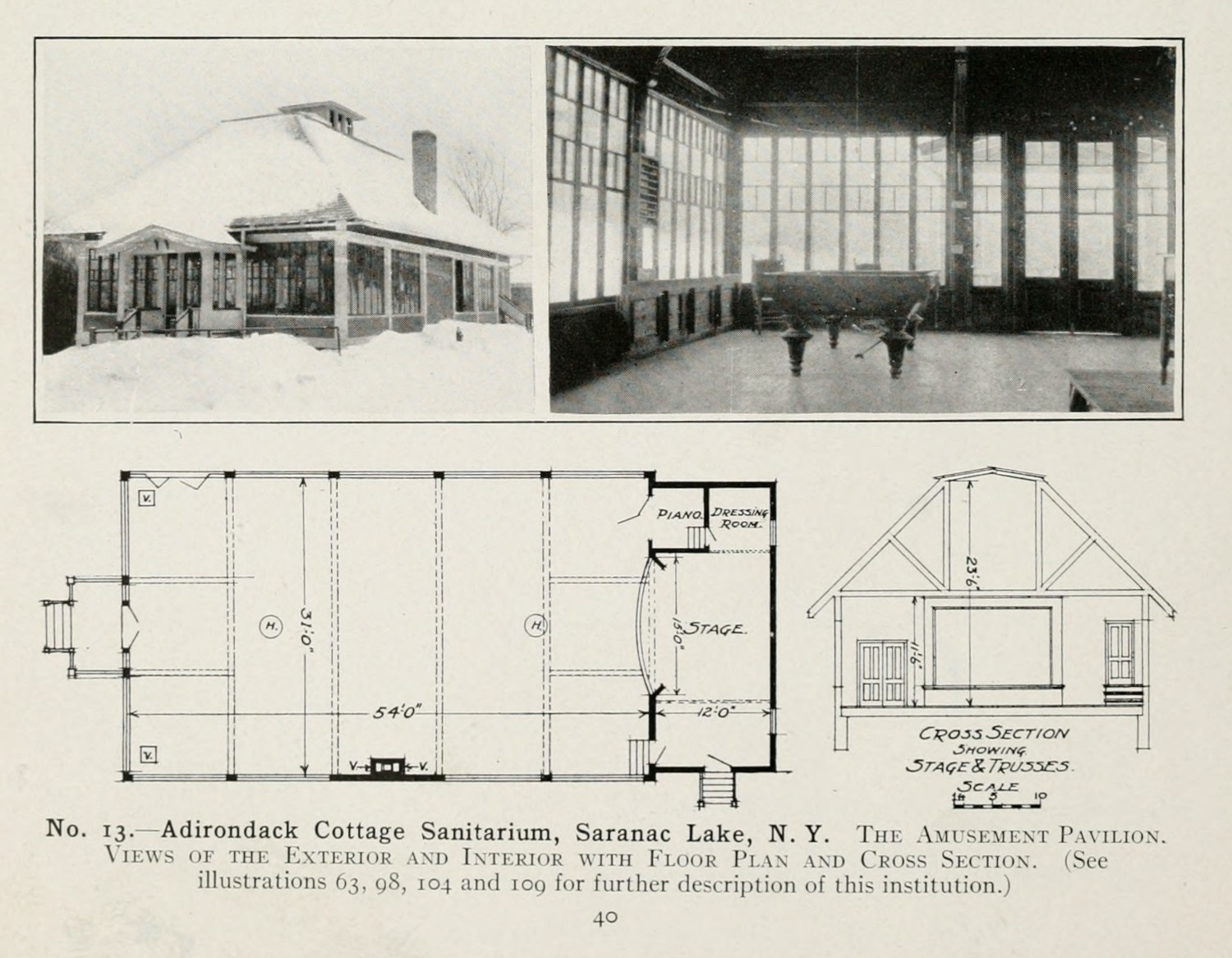

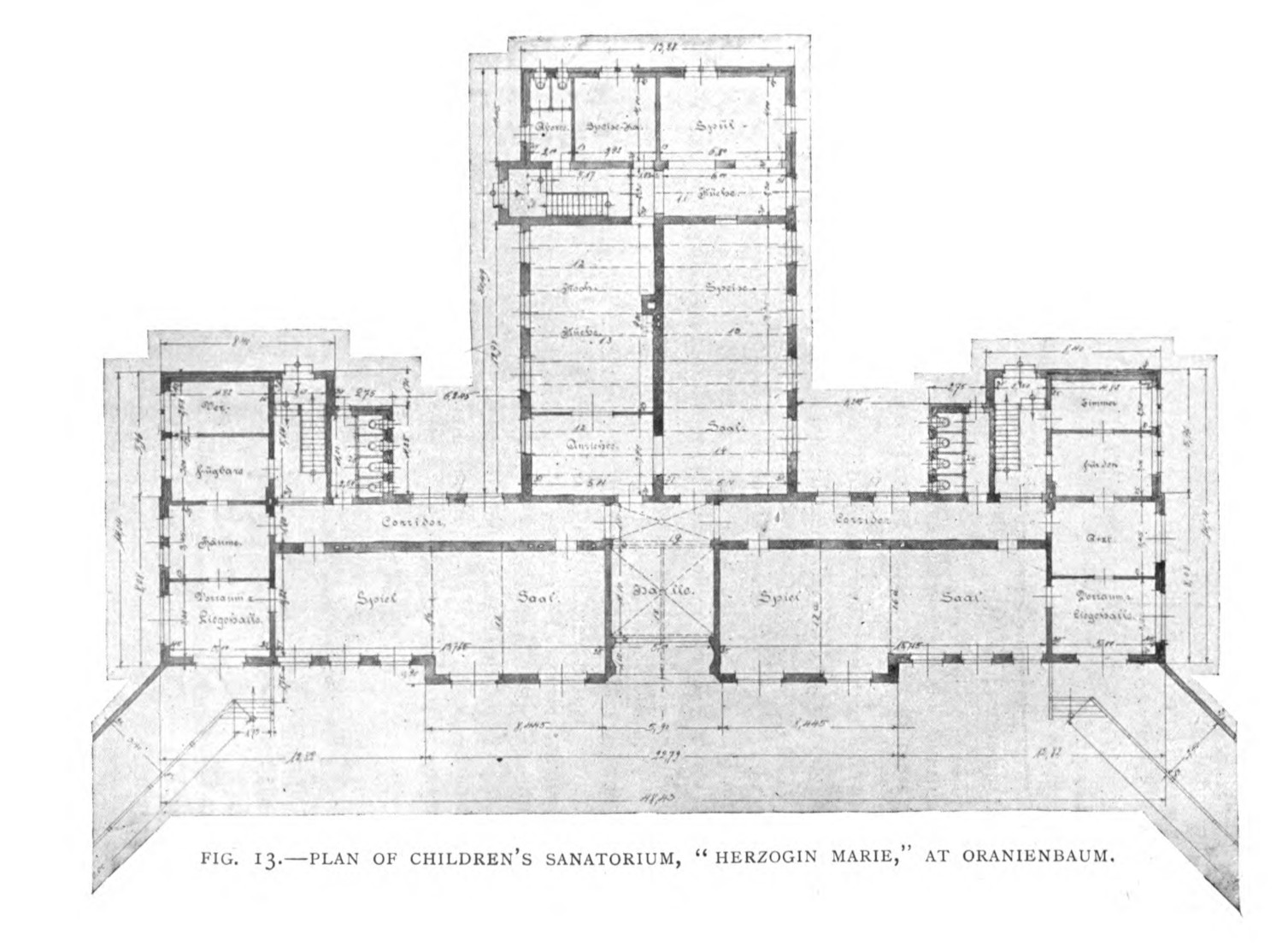

The photographs from The British Journal of Tuberculosis and Brandt’s directly show an emphasis on space: displaying the merits of a Romantic escape from the modern (1.2.2), and the stately, health improving architecture (figs. 10 - 12). Articles, books, and pamphlets often used architectural diagrams to show how doctors designed spaces that afforded a cure for tuberculosis; sometimes these spaces would afford more sunlight or airflow (1.2.4).

In my analysis, I have used language associated with consumption in this case study. Rather than referencing tubercular consumption, I instead meant to point to consumption as it is used in relation to commodities. These images are advertisements: they sell the sanatorium. I have also used this language to imply a relationship between these images and another non-clinical practice occurring in this discourse: sanatoria were being built. These images do not just correspond to spaces of healing, but also represent capital investment, whether by private enterprises or non-profit community organizations (1.2.4). These photographs document the buildings themselves, either in their newly built glory, or in the retrofitted spaces where some sanatoria were developed.9

If the period of growth in American medicine is defined by epistemic and pedagogical refinement and centralization, and by the burgeoning pharmaceutical power which began in this same moment (0.1.2), it was also aided in the very literal capitalization of land and resources. Medicine is not just the clinical gaze, or the view of the a patient as a cluster of chemical reactions, but it is also a practice that builds its solutions, through clinics, laboratories, and hospitals. The photographs of sanatoria, with their empty rooms, scant representation of patients, and their focus on the pristine climate showed the value of sanatoria. Value, here, has a double meaning (0.1.4). First these spaces were places for a cure, outfitted for microbial study, for the use of x-rays, and sometimes with spaces for autopsies (1.2.2; 1.4.1). Second, these buildings were also valuable because they were property—developed property. Understanding value in both of these senses also helps unpack some of the implicitly classed ways that doctors in the period saw their patients: if the medical practitioners could produce a safe and healthy living environment, then so should everyone else in their homes (1.3.3; 1.3.4; 1.3.5).10

-

The British Journal of Tuberculosis. (London: Ballière, Tindall & Cox, 1907), 60-61. ↩

-

Ibid., 61. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Vincent Y. Bowditch. “Three Leading Institutions as Seen Through American Eyes — The Newly Completed King’s Sanatorium, in Sussex”, The Journal of Outdoor Life 3(12). 462. ↩

-

Using the bureau of labor statistics inflation calculator (which goes back to 1913), this would equate to around $826/week for care. The number that Bowditch cites as the first proposed cost was eight guineas or, with inflation around $1,319/week for care. ↩

-

For inflation it would be roughly $329. ↩

-

Vincent Y. Bowditch. “Three Leading Institutions as Seen Through American Eyes — The Newly Completed King’s Sanatorium, in Sussex”, The Journal of Outdoor Life 3(12). 461-643. ↩

-

Brandt, Lilian. A Directory of Institutions and Societies Dealing with Tuberculosis in the United States and Canada. (New York, 1904), vii. ↩

-

Some non-profit organizations built out of spaces that were already built, like Lawrence Flick’s White Haven Sanatorium.

Bates, Barbara. Bargaining for Life: A Social History of Tuberculosis, 1876-1938. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1992. ↩

-

Bryder, Linda. Below the Magic Mountain: A Social History of Tuberculosis in Twentieth-Century Britain. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1988. ↩