Introduction

Specimen Studies

0.1.1 | 0.1.2 | 0.1.3 | 0.1.4 | 0.1.5Methods

0.2.1 | 0.2.2The Structure of this Dissertation

0.3.1Tuberculosis' Visual Culture

Visual Practices in Medical Culture

1.1.1 | 1.1.2 | 1.1.3Seeing and Settling in the Sanatorium Movement

1.2.1 | 1.2.2 | 1.2.3 | 1.2.4 | 1.2.5Teaching Public Health

1.3.1 | 1.3.2 | 1.3.3 | 1.3.4 | 1.3.5Representing Doctors in Tuberculous Contexts

1.4.1 | 1.4.2Using Human Specimens in the Study of Tuberculosis

Seeing Disease in Methyl Violet

2.1.1 | 2.1.2 | 2.1.3 | 2.1.4Case Histories

2.2.1 | 2.2.2 | 2.2.3 | 2.2.4Visceral Processes

2.3.1 | 2.3.2Relation

2.4.1 | 2.4.2 | 2.4.3Arts-Based Inquiry

Introduction

3.1.1 | 3.1.2 | 3.1.3 | 3.1.4Terminal Imaginaries & Tuberculous Imaginaries

3.2.1 | 3.2.2 | 3.2.3 | 3.2.4 | 3.2.5 | 3.2.6Dermographic Opacities

3.3.1 | 3.3.2 | 3.3.3 | 3.3.4Tactical Pretensions

3.4.1 | 3.4.2 | 3.4.3Designing Opacity

A Shift towards the Anticolonial

4.1.1 | 4.1.2 | 4.1.3 | 4.1.4Refusals and Opacities

4.2.1 | 4.2.2 | 4.2.3 | 4.2.4Digital and Ethical Workflows

4.3.1 | 4.3.2 | 4.3.3 | 4.3.4 | 4.3.5Conclusion

4.4.1Coda

Prometheus Undone

5.1.1 | 5.1.2 | 5.1.3 | 5.1.4Appendix

The Tuberculosis Corpus

X.1.1 | X.1.2 | X.1.3Web Design

X.2.1 | X.2.2 | X.2.3 | X.2.4Installation Materials

X.3.1 | X.3.2 | X.3.3Index

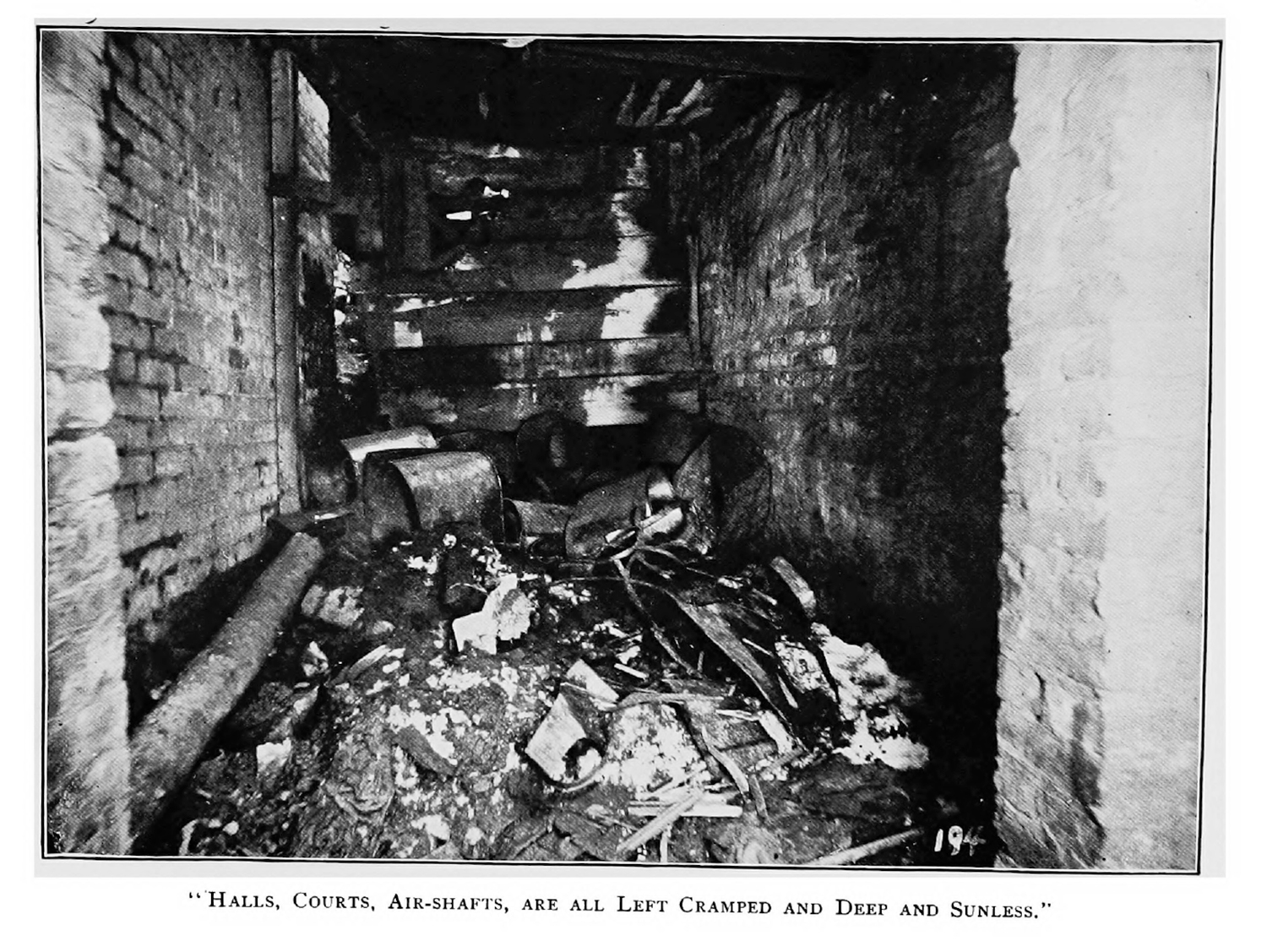

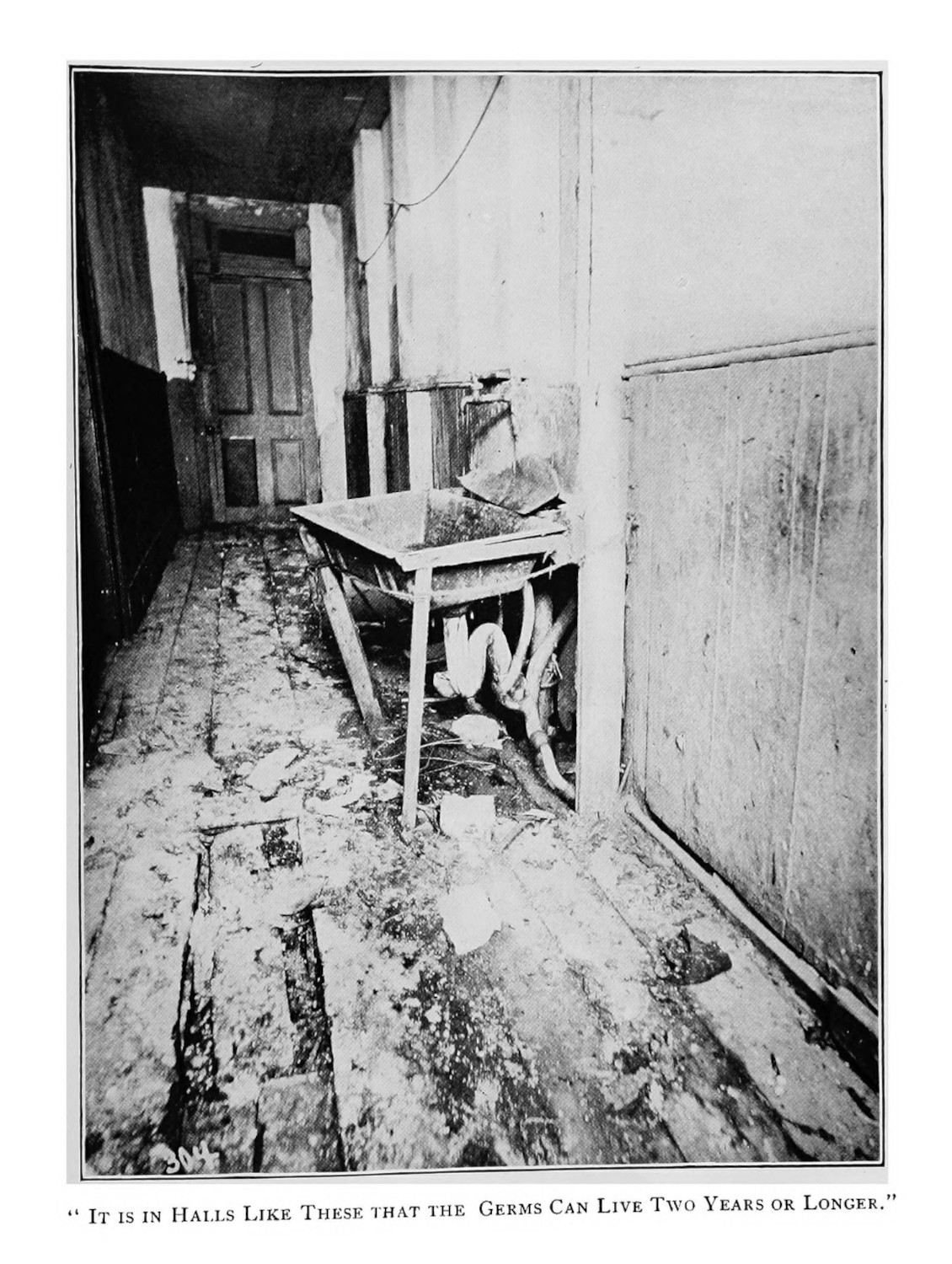

The “before” image at the Public Health Exposition discussed in the previous section is a staged example of a kind of image found in the tuberculosis corpus (1.3.1; X.1.1). Images that frame and exemplify the unhealthy environs of the urban poor appear with some regularity in the corpus’ collection. Two images are used in a handbook published by The Charity Organization Society of the City of New York (figs 1 & 2). These images accompany a first-person account by a tenement inspector. Writing of the dark, poorly ventilated spaces, in which infected air rose but never escaped from the building,

There are many other causes of darkness and foul air. All these I can show best by a story of a case in ‘‘The Bucket.” In the fourth floor rear lived an Italian and his wife, with five small children. The dark man was a hard worker, from daylight until long after dark, sewing neckties. He took the Plague [tuberculosis] in a tenement near by, which is called ‘‘The Morgue” because in the past fifteen years it has held twenty-eight cases of the Plague. They left this place and moved up-town, but could not bear the expense and so came down to this tenement on Cherry Street. The man was sick three years, still working when he could—infecting the ties he worked on. At last he stopped and went to the hospital, but soon left and came “home” to die. It is this love of wife and children that brings thousands of deaths from the Plague in the tenements. The man died in the spring of 1902. But he died too late.

This family of eight had lived in three rooms. One was a dark closet, windowless; next came the kitchen, also dark; and third, the ‘‘best room,’’ crowded with old plush furniture, with two windows looking into the court behind. Here the children lived with the father, while he slowly died.

Here the air was forever foul. From their windows the court looks like a deep pit; brick walls rise up on all four sides. It is crowded below with school sinks, and these we found unspeakably filthy, with three weazened little chaps playing hide-and-seek between them. The ground floor of the house is a pork shop, where huge cauldrons of pork fat boil day and night. Even from the roof above we noticed the sickening odor. Inspecting the cellar we found a strange odor of gas. The floor as usual was damp, uneven earth. A huge sewer main ran along one side. In this we found three gaps the size of your fist, and two rents, one eighteen inches long; hence the odor, which mingled with the other odors in the pit outside.

This air came in the front room, through the dark kitchen, into the closet behind. In this closet, seven feet by nine, slept four of the smaller children. Rosalie was a gentle little girl of seven. At night she slept in this closet. By day she watched three still younger brothers and sisters while her mother was out scrubbing. You could see her grow paler each day, so I am told by a friend from the settlement near. It was then her father came home to die.1

I use this extended excerpt to point to some of the thematic through lines that accompanied similar images. The Italian family is caught in a cycle of infection, disease and death, brought about in part by their poor wages and constant work.2 The author explicitly races and classes the family: they are Italian; they are poor; the father cannot work. The father is shown in both a positive light—a hard worker—and a negative one—constantly infecting those around him as a result of his work. This Italian family is not just the victim of this “plague” but also the progenitors of further infection.

Importantly, the authors do not direct sole blame on the family. As the author and images show (figs. 1 & 2), “The Morgue” was dangerous because it stifled airflow, because it was filthy and unkempt, because it was dark. The building actively harmed its inhabitants. Ventilation, light, and space become terms to speak to the overall quality of the space, driven by the understandings of germ theory of the period (1.3.3).

-

The Charity Organization Society of the City of New York. A Handbook on the Prevention of Tuberculosis. New York: The Charity Organization Society of New York City, 1903. 319-320. ↩

-

There is a minor slight on the next page. The author off handedly slights Italian funerary practices, “The father died. The Italians spend every cent on their funerals. So it was here. Then came even closer living—and then the hot weather.”1 While there is a tide of misfortune, which eventually leads to the death of Rosalie, there is also a comment of how to best spend money, to care for the children, to choose where and how to live.

The Charity Organization Society of the City of New York. A Handbook on the Prevention of Tuberculosis. 321. ↩