Introduction

Specimen Studies

0.1.1 | 0.1.2 | 0.1.3 | 0.1.4 | 0.1.5Methods

0.2.1 | 0.2.2The Structure of this Dissertation

0.3.1Tuberculosis' Visual Culture

Visual Practices in Medical Culture

1.1.1 | 1.1.2 | 1.1.3Seeing and Settling in the Sanatorium Movement

1.2.1 | 1.2.2 | 1.2.3 | 1.2.4 | 1.2.5Teaching Public Health

1.3.1 | 1.3.2 | 1.3.3 | 1.3.4 | 1.3.5Representing Doctors in Tuberculous Contexts

1.4.1 | 1.4.2Using Human Specimens in the Study of Tuberculosis

Seeing Disease in Methyl Violet

2.1.1 | 2.1.2 | 2.1.3 | 2.1.4Case Histories

2.2.1 | 2.2.2 | 2.2.3 | 2.2.4Visceral Processes

2.3.1 | 2.3.2Relation

2.4.1 | 2.4.2 | 2.4.3Arts-Based Inquiry

Introduction

3.1.1 | 3.1.2 | 3.1.3 | 3.1.4Terminal Imaginaries & Tuberculous Imaginaries

3.2.1 | 3.2.2 | 3.2.3 | 3.2.4 | 3.2.5 | 3.2.6Dermographic Opacities

3.3.1 | 3.3.2 | 3.3.3 | 3.3.4Tactical Pretensions

3.4.1 | 3.4.2 | 3.4.3Designing Opacity

A Shift towards the Anticolonial

4.1.1 | 4.1.2 | 4.1.3 | 4.1.4Refusals and Opacities

4.2.1 | 4.2.2 | 4.2.3 | 4.2.4Digital and Ethical Workflows

4.3.1 | 4.3.2 | 4.3.3 | 4.3.4 | 4.3.5Conclusion

4.4.1Coda

Prometheus Undone

5.1.1 | 5.1.2 | 5.1.3 | 5.1.4Appendix

The Tuberculosis Corpus

X.1.1 | X.1.2 | X.1.3Web Design

X.2.1 | X.2.2 | X.2.3 | X.2.4Installation Materials

X.3.1 | X.3.2 | X.3.3Index

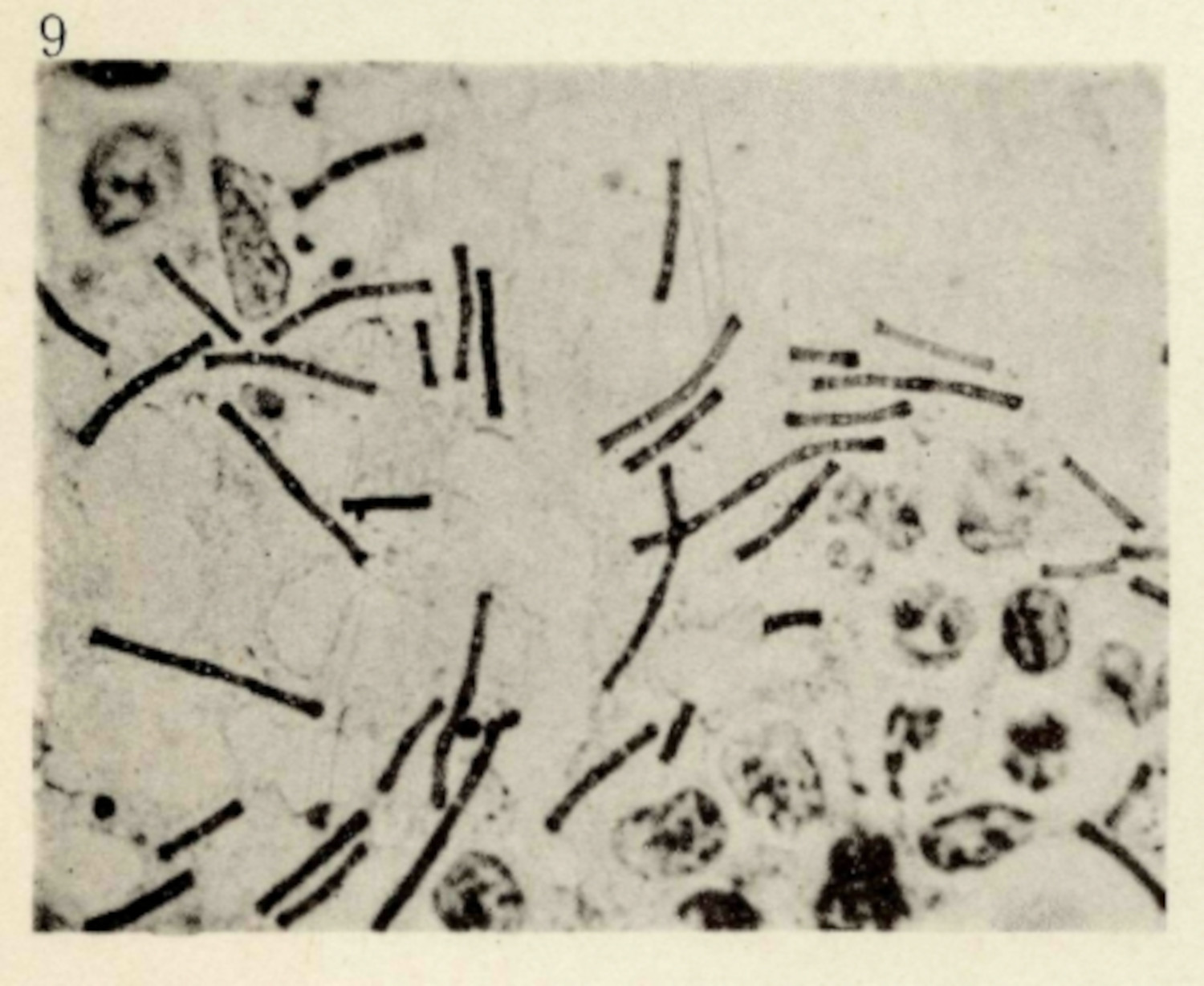

Robert Koch was already known as a prominent bacteriologist when he delivered his essay Aetiology of Tuberculosis in Berlin in 1882. He had, a decade prior, used microphotography to prove the bacterial origin of anthrax (fig. 1), and had returned to present his findings on tuberculosis to the Berlin Physiological Society. Koch had chosen this arena, and not the Pathological Society, because “the latter society was . . . dominated by the eminent Professor of Pathology, Rudolf Virchow. . . . Virchow had not yet accepted the germ theory of infections and had been highly critical of Koch’s earlier work.”1 Koch quietly walked his audience through his findings, with dozens of specimens around him, proving to the skeptical group of medical scientists the bacterial origins of tuberculosis—Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

Koch’s findings resulted in a sea change around scientific understandings of tuberculosis: the disease that was thought to be a hereditary, constitutional malady was, in fact, a contagious one.2 His findings ushered in the public health, hygienic, and social interventions against the disease in the period (1.3.1; 1.3.4; 1.3.5). Furthermore, Koch’s bacteriological claims were the basis for scientific research into the disease and the authority of some of the most prominent medical researchers in the United States. In 1885 Edward Livingston Trudeau, founder of the Adirondack Cottage Sanitarium,3 began operating a small laboratory, from which he published studies regarding the disease (1.2.1; 1.2.2); this lab grew with the sanatorium, bolstered by the inclusion of Edward R. Baldwin and then a cadre of other scientists, like Lawrason Brown.4 Other prominent researchers, like H. J. Corper from the City of Chicago Municipal Sanitorium and later National Jewish Hospital for Consumptives (1.2.4), published regularly using bacteriological methods to discuss various aspects of the disease.

Koch’s research was bolstered by two practices. The first was a theoretical one, known as Koch’s postulates, the logic of which proves the existence of a bacterium and its cause of a disease (2.1.3). The other practice was a rhetorical one: he used more than two hundred specimens as part of his presentation, which visually displayed every step in his process.5 In an extremely skeptical space, these specimens bolstered support for his bacteriological claims. The experiment was laid out as self-evident, which could be seen as true by even the most intransigent anti-germ theory scientist.

To start this chapter, I want to take an extended look at Koch’s original bacteriological study, to describe, with a non-human example, some of the theoretical and conceptual ideas regarding the visual culture around biomedical specimens. Part of this work will delineate some of the cultural practices which undergird much of the naturalism in the sciences—that is the objective fact as presented in a scientific experiment.6 For Koch’s argument to be convincing, doctors had to be trained in microscopy and histology, and for doctors to be trained in these technologies there too needed to be changes in optics and chemistry. For Mycobacterium tuberculosis to appear self-evident required a great deal of other influential processes which informed scientific understanding.

I want to use Koch’s research to define a method for medial media studies research into non-photographic, non-filmic, and non-digital research. While Koch had worked with microphotography for his work on anthrax, he had not been able to apply these methods to tuberculosis; however, so much of his research relies on technological and chemical processes that make scientific representation seem self-evident.7 Histochemical methods, the ones that Koch used to make Mycobacterium tuberculosis appear under the microscope, are also means of mediating the natural world, and they are distinct from photochemical ones. Traditional media approaches cannot be taken whole cloth and applied in this case, offering an opportunity to think through an approach to non-filmic and non-digital media in medical sciences. I look to Koch’s research to show the value of media studies in the study and critique of medical knowledge work. I specifically argue for a media studies that, as Lisa Gitelman argues, looks to the “‘little tools of knowledge’, in addition to larger, glitzier—that is, more intensively capitalized—forms.”8 While I will be relying heavily on photographic materials later in this chapter, my interest is less in the mechanical reproducibility afforded by the technology,9 so much as to ruminate on the other material, mechanical, and cultural processes required for the production of wet tissue specimens (2.2.1; 2.3.1; 2.3.2). Much has been written about clinical photography10 and so my goal is to tease at the various interrelated material, technological and cultural practices that produce a research object that can be imaged in a scientific context.

Koch’s research provides an excellent place to develop an approach and method to interrogate medical science research from the perspective of media studies. His work was a confluence of practices: the careful maintenance of life and death in guinea pigs (2.1.4), the dying of tissues of tuberculous specimens (2.1.3), and the inspection of those materials under the microscope (2.1.3). Control of life and death saturates these methods, as too does the cultural and technological presumptions that enabled the representations in the first place.

I start with Koch and his research to define how the biomedical specimen functions in a research context. This chapter, however, is not about Koch. I use this beginning case study to think through how the creation of specimens is linked to the historical, cultural and material context in which a research subject died. Koch’s processes, intricate and detailed as they are, reveal how much labor is put into the production of a research object, and how convincing those research objects can be for even the most critical observer.

-

Daniel, Thomas M. Captain of Death: The Story of Tuberculosis. New York: University of Rochester Press, 1997. 60. ↩

-

The link of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to tuberculosis was generally accepted at a global level; however, there was still a great deal of discussion regarding how one’s susceptibility to the germ was hereditary.

Feldberg, Georgina D. Disease and Class: Tuberculosis and the Shaping of Modern North American Society. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1995. ↩

-

A note on spelling here: I have adopted the use of sanatorium as the standardized spelling for this dissertation. Some institutions spelled it differently. I will use their spelling when using the name of the institution directly. ↩

-

Baldwin and Brown are prominent researchers in the tuberculosis corpus.

Trudeau, Edward Livingston. An Autobiography. Garden City & New York: Doubleday, Doran & Company, Inc., 1944. 201-230. ↩

-

Daniel, Thomas M. Captain of Death: The Story of Tuberculosis. New York: University of Rochester Press, 1997. 82.

Moreover as René and Jean Dubos argue, in the complete paper, “he presented records of bacteriological studies on ninety-eight cases of human and thirty-four cases of animal tuberculosis. He inoculated four hundred and ninety-six experimental animals, recovered forty-three pure bacillary cultures, and tested their virulence in two hundred animals.”

Dubos, René, and Jean Dubos. The White Plague: Tuberculosis, Man, and Society. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1952. 105. ↩

-

Much of my thinking in this regard is influenced by Bruno Latour’s examination and critique of Steven Shapin and Simon Shaffer’s Leviathan and the Air-Pump.

Shapin, Steven, and Simon Schaffer. Leviathan and the Air-Pump: Hobbes, Boyle, and the Experimental Life. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 1985; Latour, Bruno. We Have Never Been Modern. Translated by Catherine Porter. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1993. ↩

-

Latour, Bruno. “Drawing Things Together.” In Representation in Scientific Practice, edited by Michael Lynch and Steve Woolgar, 19–68. Cambridge & London: The MIT Press, 1990. ↩

-

Gitelman, Lisa. Paper Knowledge: Toward a Media History of Documents. Duke University Press, 2014. 19. ↩

-

Benjamin, Walter. “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” In Walter Benjamin: Selected Writings Volume 3 1935-1938, edited by Howard Eiland and Michael W. Jennings, translated by Edmund Jephcott and Harry Zohn, 102–33. Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2002. ↩

-

O’Connor, Erin. “Camera Medica.” History of Photography 23, no. 3 (1999): 232–44; Rawling, Katherine D. B. “‘She Sits All Day in the Attitude Depicted in the Photo’: Photography and the Psychiatric Patient in the Late Nineteenth Century.” Medical Humanities 43, no. 2 (2017): 99–110; Stabile, Carol A. “Shooting the Mother: Fetal Photography and the Politics of Disappearance.” Camera Obscura 10, no. 1 (1992): 179–205; Tucker, Jennifer. Nature Exposed: Photography as Eyewitness in Victorian Science. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005; Curtis, Scott. “Photography and Medical Observation.” In The Educated Eye, edited by Nancy Anderson and Michael R. Dietrich, 68–93. Hanover: Dartmoth College Press, 2016. ↩