Introduction

Specimen Studies

0.1.1 | 0.1.2 | 0.1.3 | 0.1.4 | 0.1.5Methods

0.2.1 | 0.2.2The Structure of this Dissertation

0.3.1Tuberculosis' Visual Culture

Visual Practices in Medical Culture

1.1.1 | 1.1.2 | 1.1.3Seeing and Settling in the Sanatorium Movement

1.2.1 | 1.2.2 | 1.2.3 | 1.2.4 | 1.2.5Teaching Public Health

1.3.1 | 1.3.2 | 1.3.3 | 1.3.4 | 1.3.5Representing Doctors in Tuberculous Contexts

1.4.1 | 1.4.2Using Human Specimens in the Study of Tuberculosis

Seeing Disease in Methyl Violet

2.1.1 | 2.1.2 | 2.1.3 | 2.1.4Case Histories

2.2.1 | 2.2.2 | 2.2.3 | 2.2.4Visceral Processes

2.3.1 | 2.3.2Relation

2.4.1 | 2.4.2 | 2.4.3Arts-Based Inquiry

Introduction

3.1.1 | 3.1.2 | 3.1.3 | 3.1.4Terminal Imaginaries & Tuberculous Imaginaries

3.2.1 | 3.2.2 | 3.2.3 | 3.2.4 | 3.2.5 | 3.2.6Dermographic Opacities

3.3.1 | 3.3.2 | 3.3.3 | 3.3.4Tactical Pretensions

3.4.1 | 3.4.2 | 3.4.3Designing Opacity

A Shift towards the Anticolonial

4.1.1 | 4.1.2 | 4.1.3 | 4.1.4Refusals and Opacities

4.2.1 | 4.2.2 | 4.2.3 | 4.2.4Digital and Ethical Workflows

4.3.1 | 4.3.2 | 4.3.3 | 4.3.4 | 4.3.5Conclusion

4.4.1Coda

Prometheus Undone

5.1.1 | 5.1.2 | 5.1.3 | 5.1.4Appendix

The Tuberculosis Corpus

X.1.1 | X.1.2 | X.1.3Web Design

X.2.1 | X.2.2 | X.2.3 | X.2.4Installation Materials

X.3.1 | X.3.2 | X.3.3Index

At the center of Koch’s work were two epistemic underpinnings: first, was the expression of Koch’s postulates—a logical framework that helps prove the presence of bacteria in a given sample. And second, is a representational practice that supports and confirms these ideas. The second underpinning was the visual representation of those postulates for a discerning viewer. For this chapter what I most care about the latter underpinning, but it is worth discussing Koch’s postulates in some detail. They are quite famous in the history of germ theory, and one of the reasons why medical scientists revere Koch’s contributions. To prove the presence of bacteria,

It was necessary to isolate the bacilli from the body; to grow them in pure culture. . . : and, by administering the isolated bacilli to animals, to reproduce the same morbid condition which, as known, is obtained by inoculation with spontaneously developed tuberculous material.1

Koch’s postulates stress the isolation of a single variable—the bacteria in question—which can be traced from one sick animal subject to another animal subject through a series of environmental changes. The bacteria is isolated and then followed from a sick subject to a non-contaminated sample and to a healthy subject, who then became sick with tuberculosis. Koch specifically used laboratory animals for this research, relying on guinea pigs as the seat of his bacteriological experiments. This process required infecting these test subjects and letting them die, so that they may be autopsied for tubercules, and the bacteria within (2.1.4).

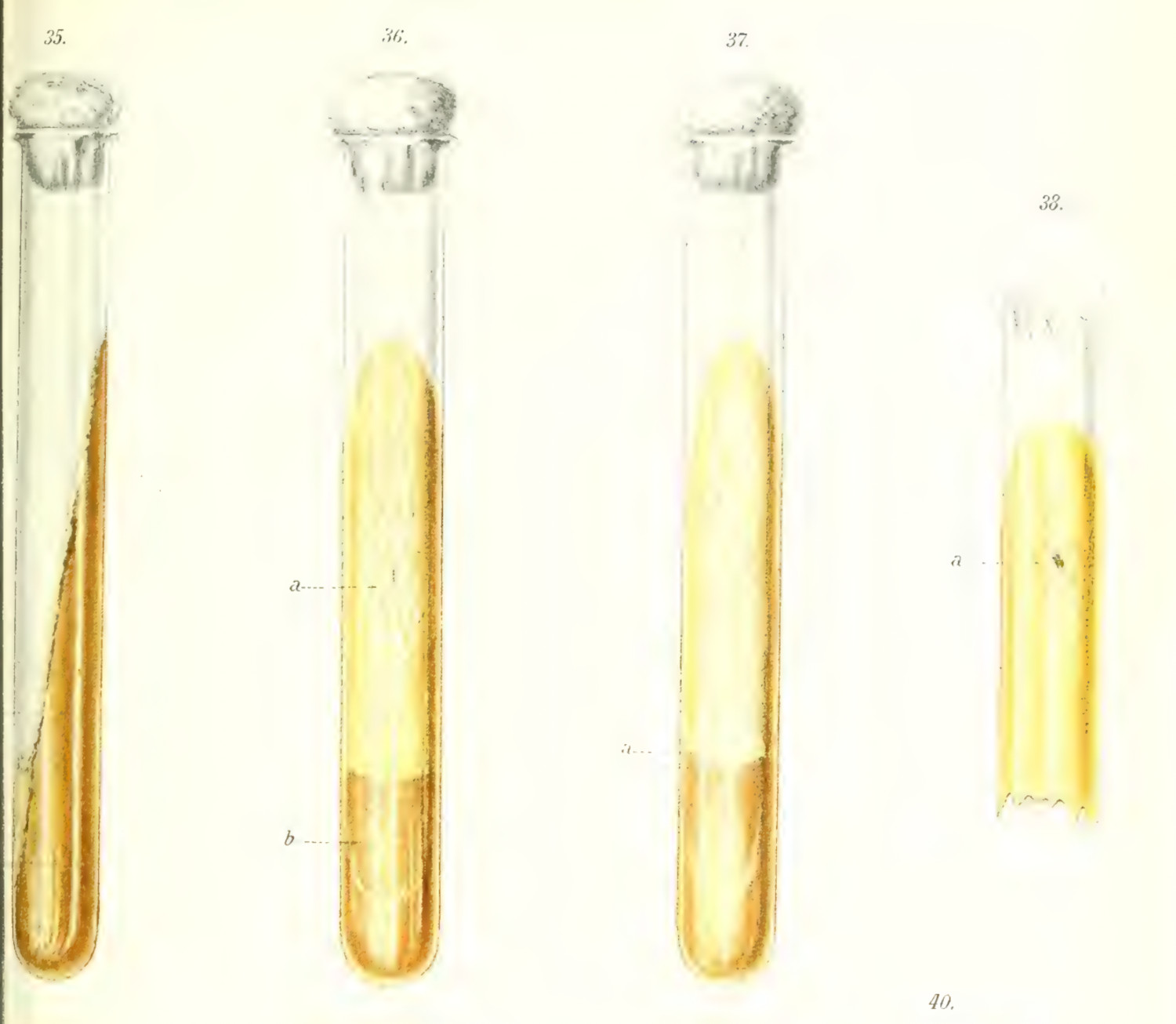

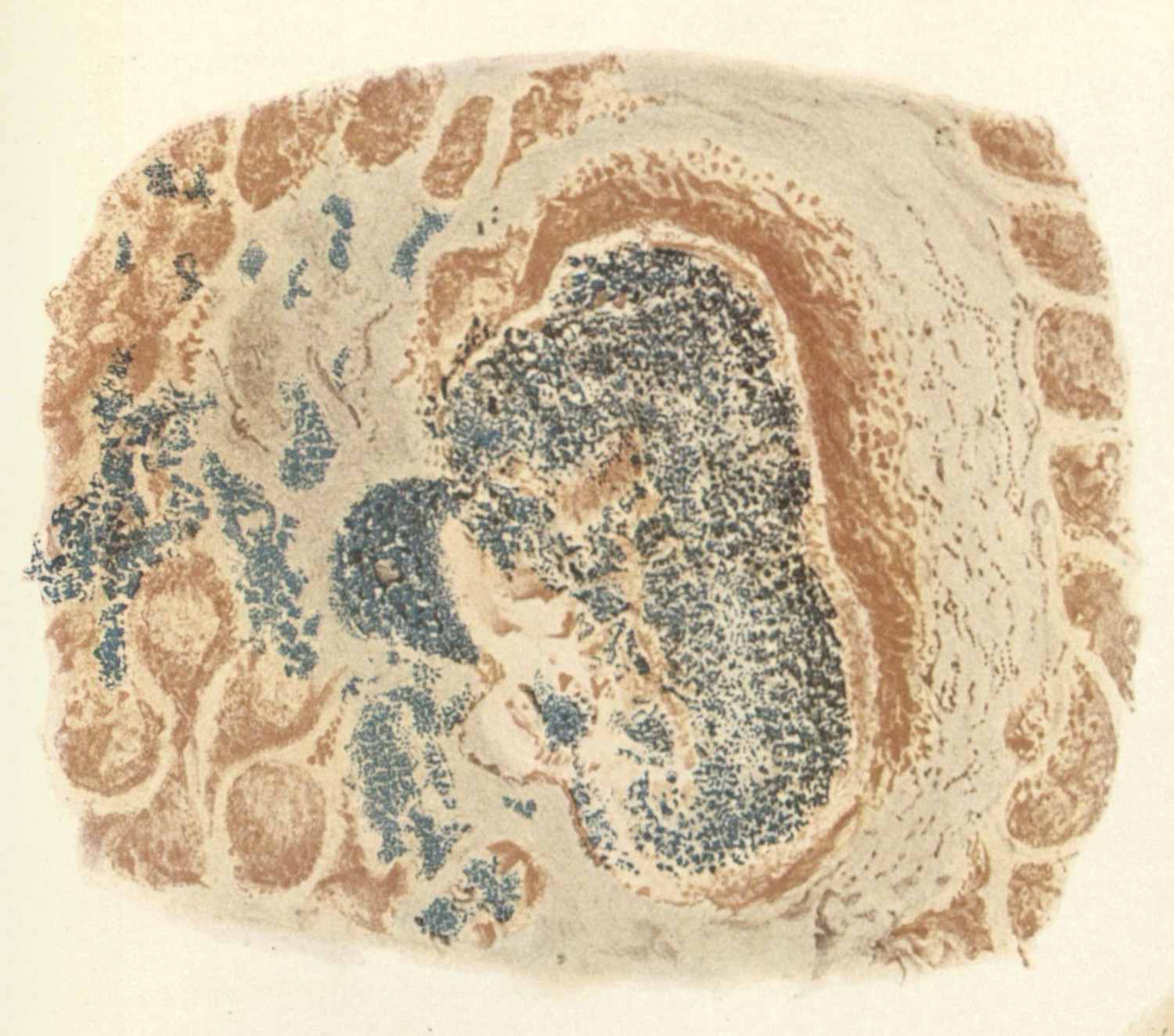

With Koch’s postulates there was a conceptual and theoretical grounding for the work in the paper, but there was a bigger issue: the German bacteriologist was working to convince a group of his peers—the hostile scientists of the German academy—of the legitimacy of germ theory. To address potential concerns, Koch presented his essay with two hundred prepared demonstrations (2.1.1).2 These demonstrations showed the process of his work, and let his colleagues experience, first-hand, the validity of the research. He showed his research step-by-step: the visible pathology of tuberculosis found in lab animals at autopsy, which correspond to the presence of bacterial colonies in the sterilized serum—itself a visual representation of the isolated germ (fig. 1)—and the resulting materials extracted from animals injected with the isolated serum.3

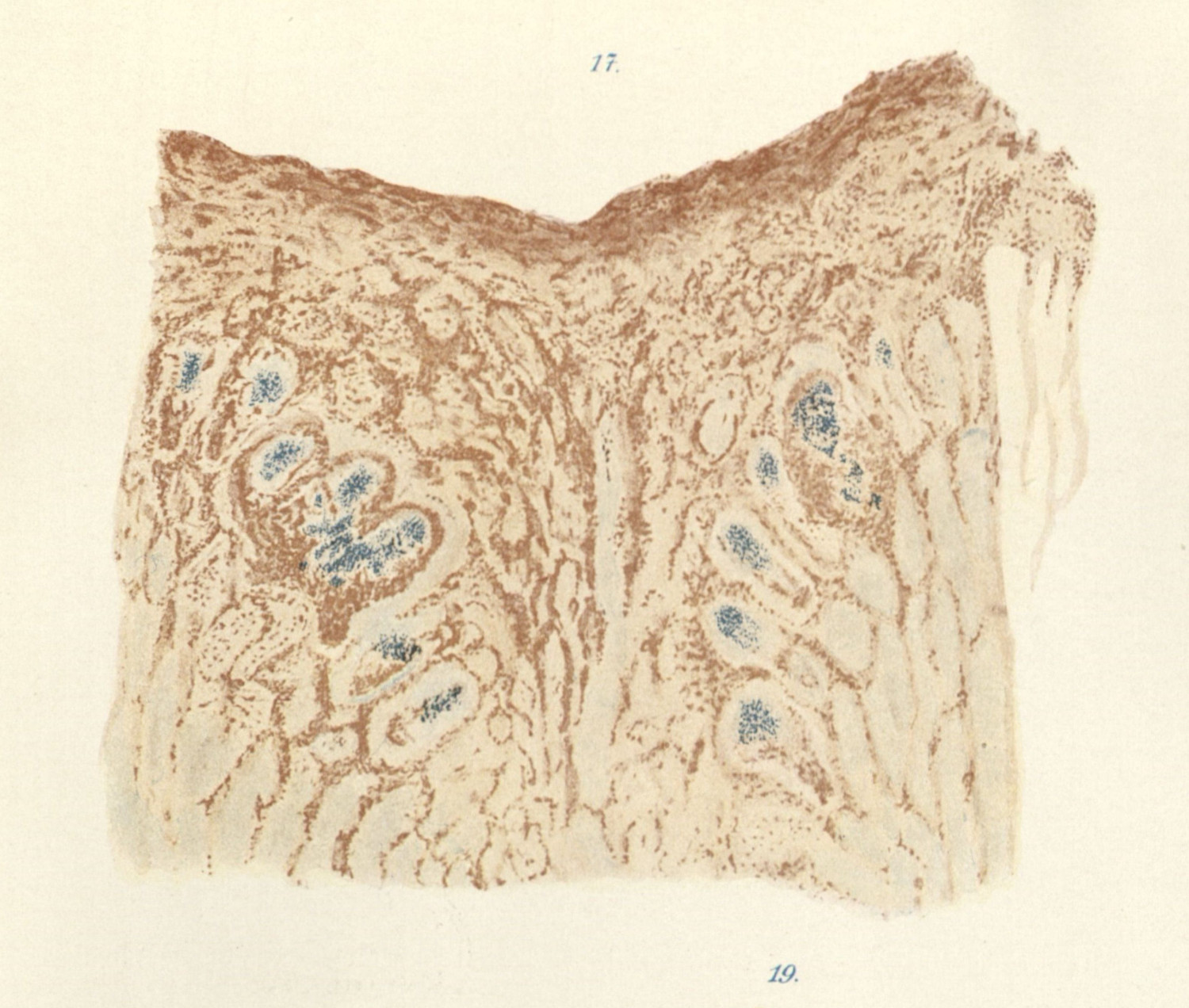

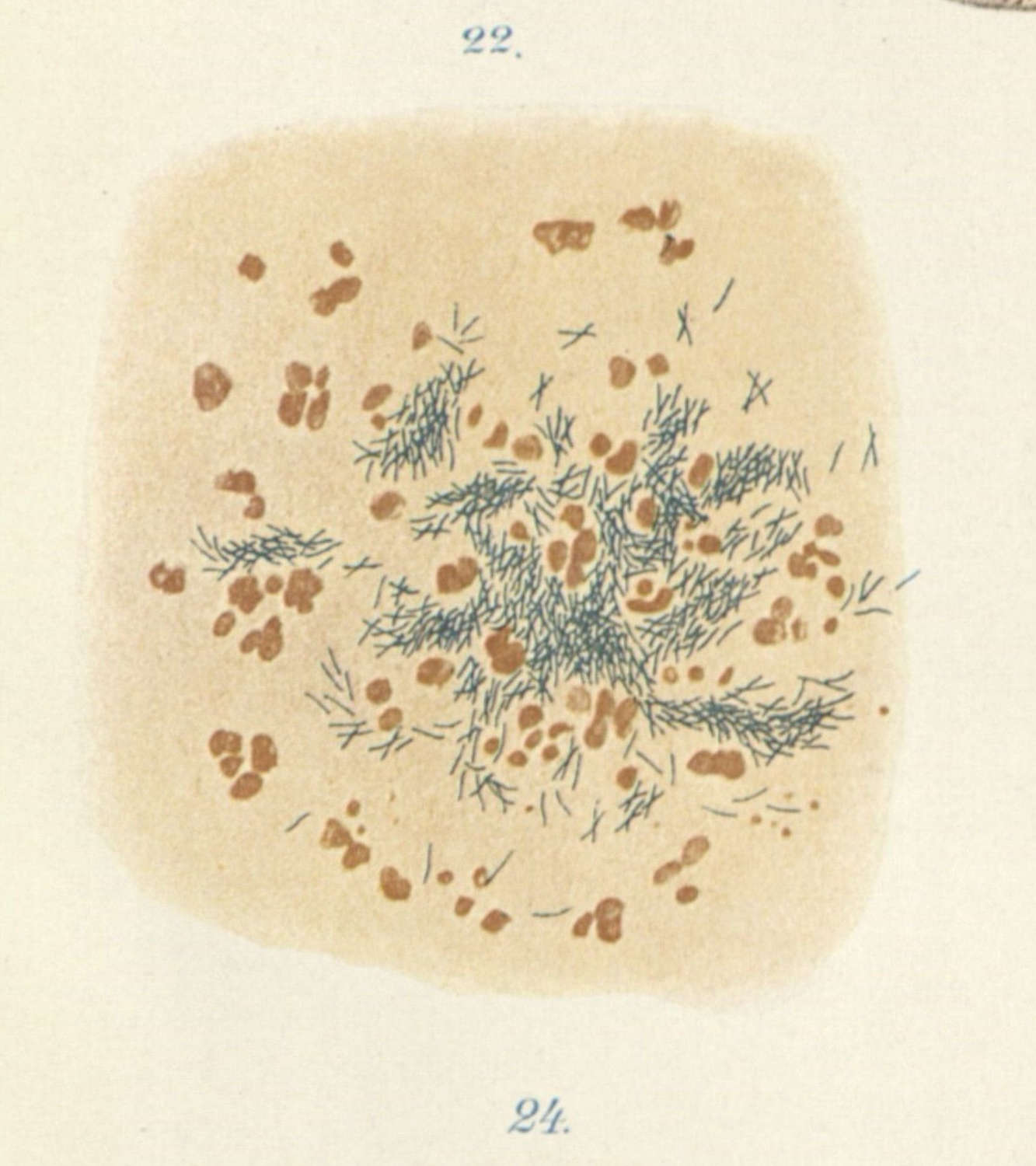

What I want to stress here is Koch’s reliance on external objects, and the obvious visibility in these transformations. Mycobacterium tuberculosis may be traced by symptoms between one test animal and another, but there is always a visual register that confirms its presence: either in the slow growth of a bacterial colony in pure culture which can be spotted by the naked eye, or by the obvious presence of the bacteria when dyed inspected under the microscope (figs. 1 -2) (2.1.3).

An embodied material history was required for the specimen to function: an observer was assumed to be able link the continuity between a series of guinea pigs, the bacteria which propagated inside them, which was cultured in isolation, reintroduced to new guinea pigs, and then displayed again upon their death (2.1.4; 2.2.4). The proof was dependent on an interconnected history, which is distilled in concrete moments of visual examination (2.2.3). Koch’s proof rests not only the intricately dyed Mycobacterium tuberculosis which bloomed under the microscope (fig. 3-4) (2.1.3), but also on a continuity between observable phenomena which tied together the experiment’s narrative.

The kind of experimental and rhetorical apparatus which Koch deployed corresponds with the approach to the sciences described by Steven Shapin and Simon Schaffer in Leviathan and the Air-Pump, where the political sphere is dispelled in a scientific demonstration, so that only the natural object can be inspected and understood.4 Important here was that Koch’s demonstrations played into an acutely visual realm, relying as he did on the technology of the microscope. In this context, then, the representational practice of acquiring, staining, displaying, and reading examples of the microbial world becomes significant, so as to further underline the logical framework of Koch’s postulates. Each move, from sick animal, to pure sample, to inoculation, to examination, required an acceptance of, and agreement on, the phenomena that had been produced for the scientific observer.5

-

Koch, Robert. “Die Aetiologie Der Tuberculose.” Translated by Berna Pinner and Max Pinner. American Review of Tuberculosis, no. 25 (1932): 306. Quoted in Daniel, Thomas M. Captain of Death: The Story of Tuberculosis. New York: University of Rochester Press, 1997. 81.

I use this quote to point to Daniel’s succinct summary of Koch’s work. Daniel’s monograph helps show a nuance which I am unable to address in this study regarding Koch’s distillation of the work of his mentor, Jacob Henle. ↩

-

Daniel, Thomas M. Captain of Death: The Story of Tuberculosis. New York: University of Rochester Press, 1997. 82.

Moreover as René and Jean Dubos note, Koch “presented records of bacteriological studies on ninety-eight cases of human and thirty-four cases of animal tuberculosis. He inoculated four hundred and ninety-six experimental animals, recovered forty-three pure bacillary cultures, and tested their virulence in two hundred animals.”

Dubos, René, and Jean Dubos. The White Plague: Tuberculosis, Man, and Society. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1952. 105. ↩

-

Dubos, René, and Jean Dubos. The White Plague: Tuberculosis, Man, and Society. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1952. 103. ↩

-

Shapin, Steven, and Simon Schaffer. Leviathan and the Air-Pump: Hobbes, Boyle, and the Experimental Life. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 1985. ↩

-

I will not go into detail about the social history of microscopy in this chapter. The scholars who have examined this history have shared how the relationship between microscopy and scientific use was both technological and cultural.

Bennett, J. A. “The Social History of the Microscope.” Journal of Microscopy 155, no. 3 (1989): 267–80; Bracegirdle, Brian. “J. J. Lister and the Establishment of Histology.” Medical History 21 (1977): 187–91; Bracegirdle, Brian. “The History of Histology: A Brief Survey of Sources.” History of Science 15 (1977): 77–101; Gooday, Grame. “‘Nature’ in the Laboratory: Domestication and Discipline with the Microscope in Victorian Life Science.” The British Journal for the History of Science 24, no. 3 (1991): 307–41; Jacyna, L. S. “‘A Host of Experienced Microscopists’: The Establishment of Histology in Nineteenth-Century Edinburgh.” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 75, no. 2 (2001): 225–53; La Berge, Ann. “The History of Science and the History of Microsopy.” Perspectives on Science 7, no. 1 (1999); Wick, Mark. “Histochemistry as a Tool in Morphological Analysis: A Historical Review.” Annals of Diagnostic Pathology 16 (2012): 71–76. ↩