Introduction

Specimen Studies

0.1.1 | 0.1.2 | 0.1.3 | 0.1.4 | 0.1.5Methods

0.2.1 | 0.2.2The Structure of this Dissertation

0.3.1Tuberculosis' Visual Culture

Visual Practices in Medical Culture

1.1.1 | 1.1.2 | 1.1.3Seeing and Settling in the Sanatorium Movement

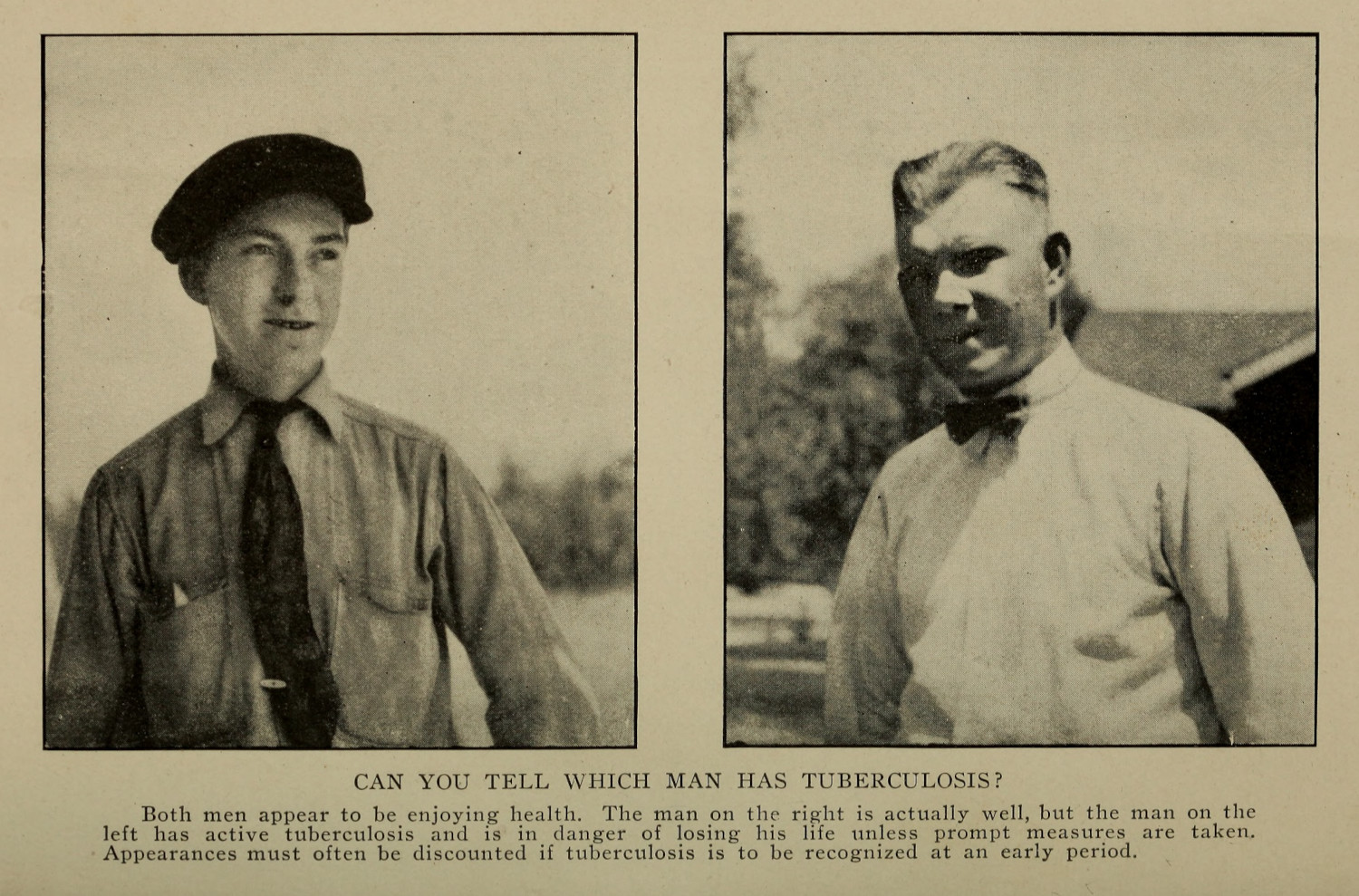

1.2.1 | 1.2.2 | 1.2.3 | 1.2.4 | 1.2.5Teaching Public Health

1.3.1 | 1.3.2 | 1.3.3 | 1.3.4 | 1.3.5Representing Doctors in Tuberculous Contexts

1.4.1 | 1.4.2Using Human Specimens in the Study of Tuberculosis

Seeing Disease in Methyl Violet

2.1.1 | 2.1.2 | 2.1.3 | 2.1.4Case Histories

2.2.1 | 2.2.2 | 2.2.3 | 2.2.4Visceral Processes

2.3.1 | 2.3.2Relation

2.4.1 | 2.4.2 | 2.4.3Arts-Based Inquiry

Introduction

3.1.1 | 3.1.2 | 3.1.3 | 3.1.4Terminal Imaginaries & Tuberculous Imaginaries

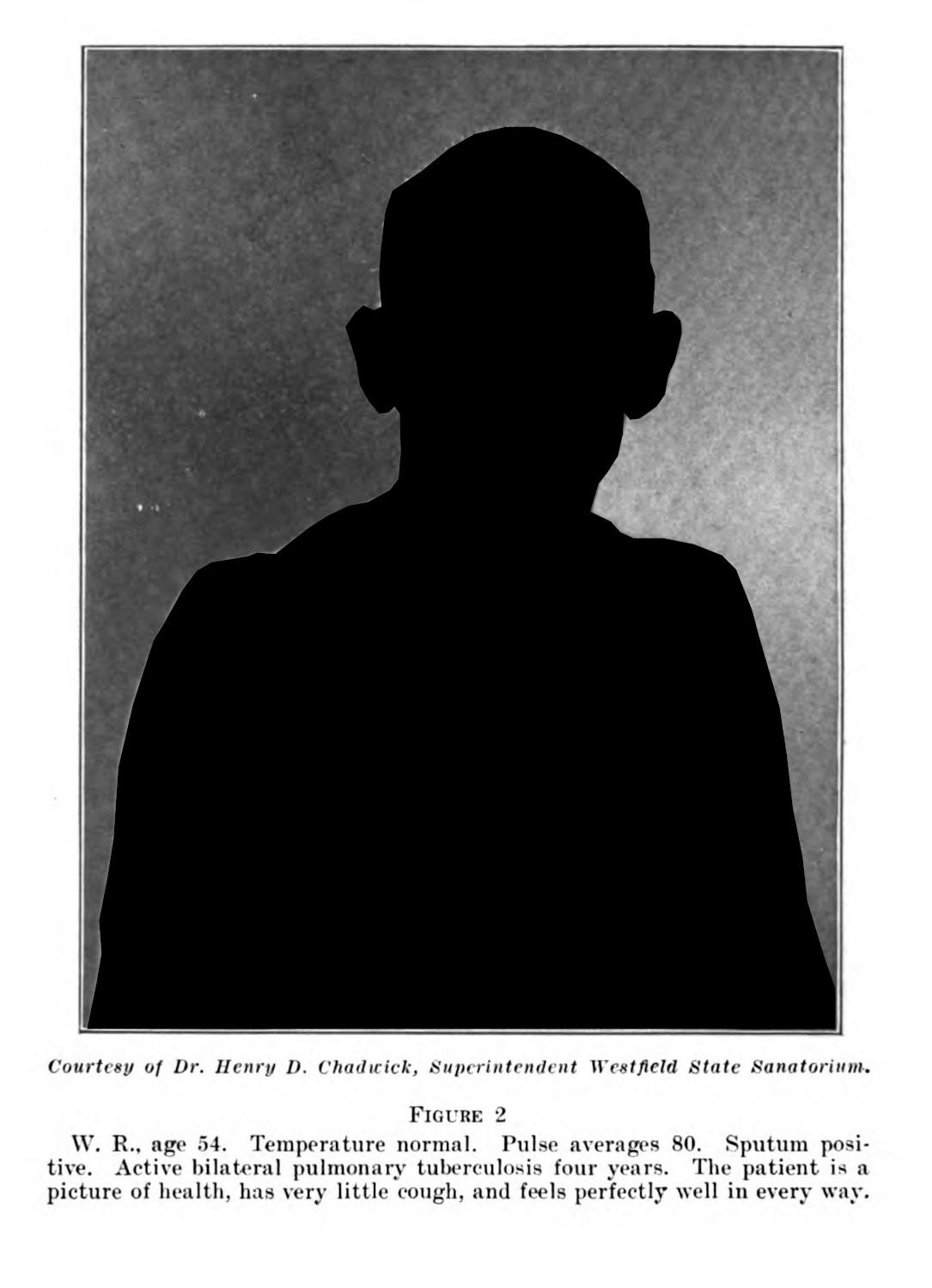

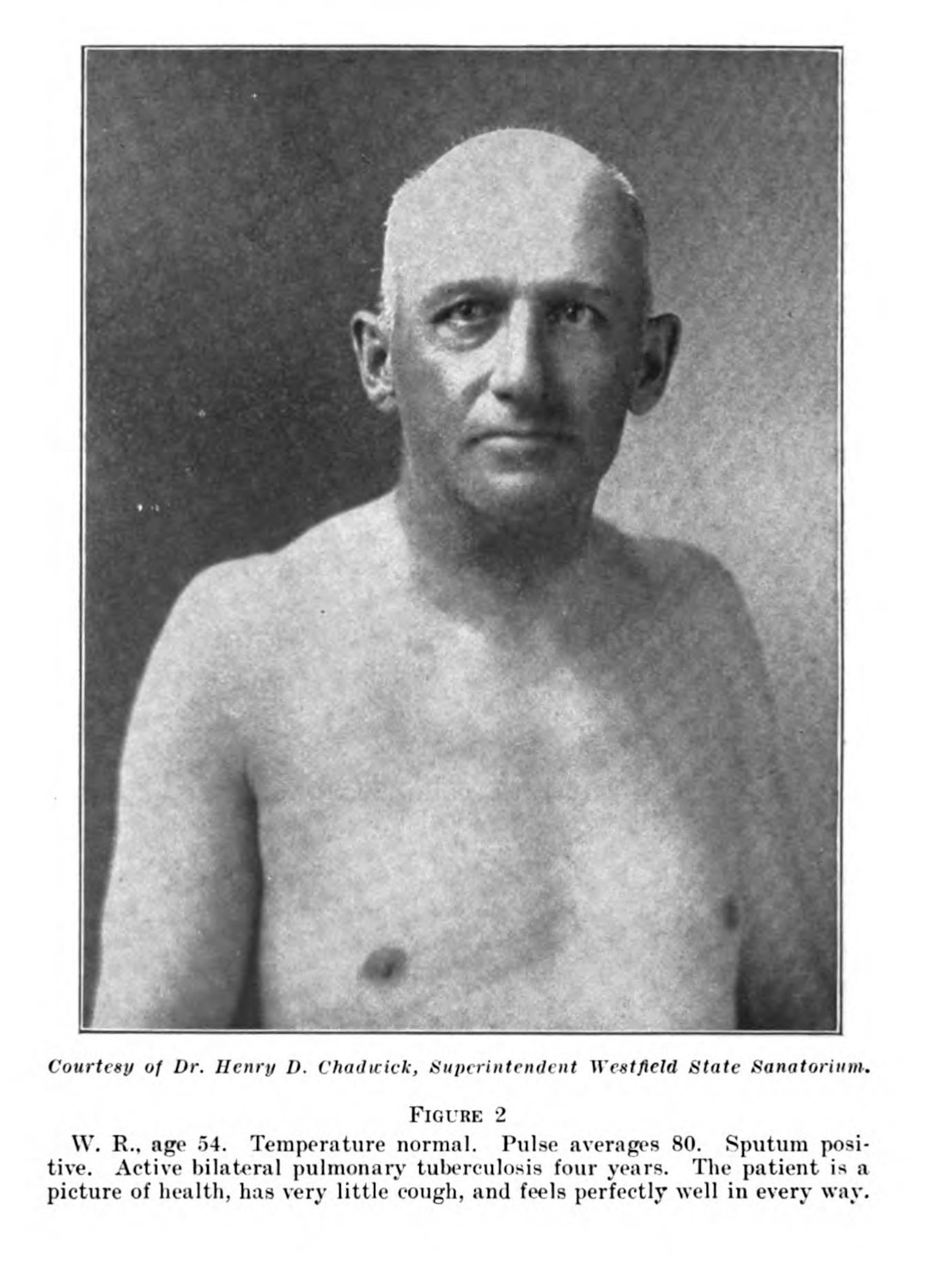

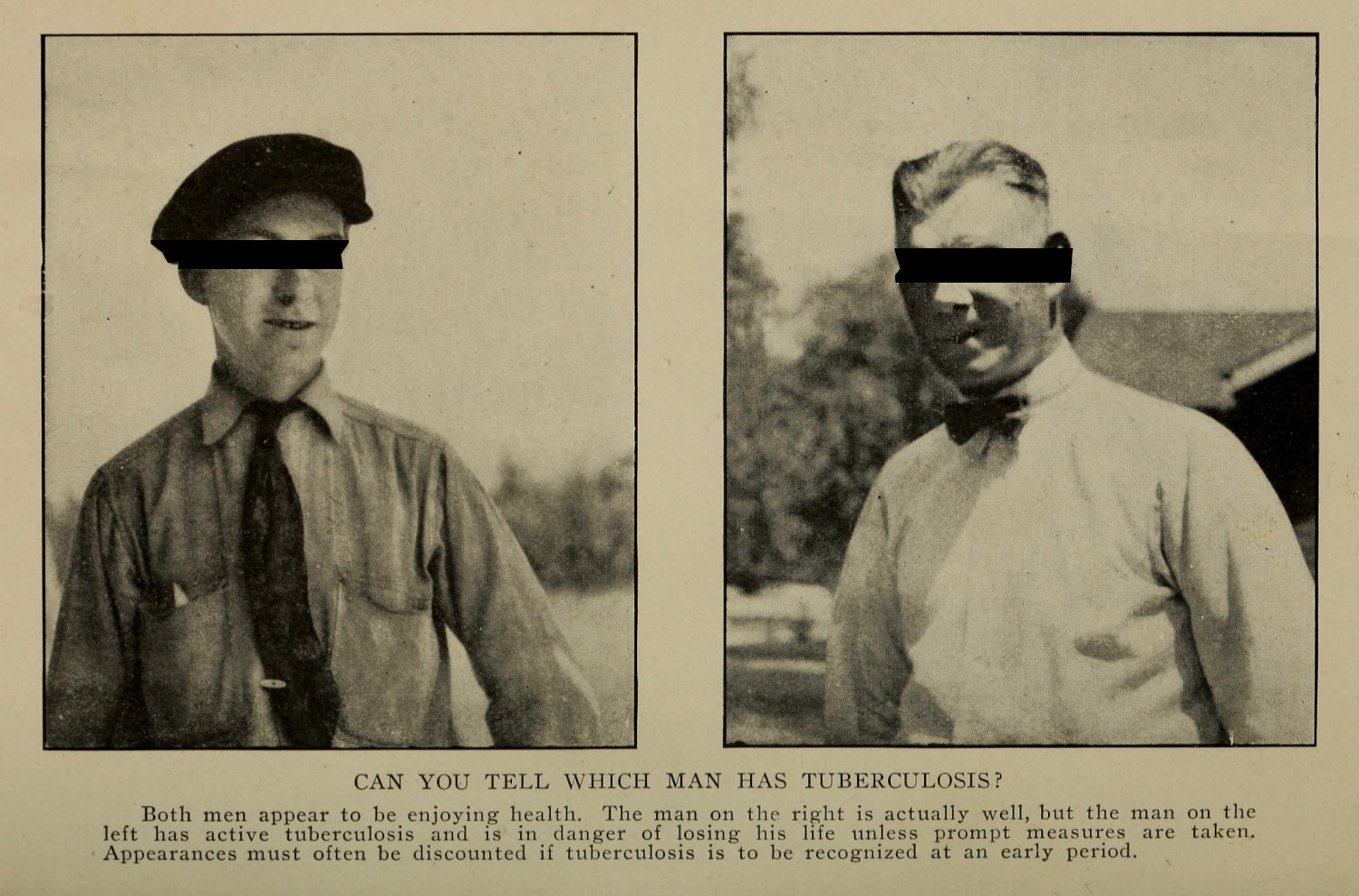

3.2.1 | 3.2.2 | 3.2.3 | 3.2.4 | 3.2.5 | 3.2.6Dermographic Opacities

3.3.1 | 3.3.2 | 3.3.3 | 3.3.4Tactical Pretensions

3.4.1 | 3.4.2 | 3.4.3Designing Opacity

A Shift towards the Anticolonial

4.1.1 | 4.1.2 | 4.1.3 | 4.1.4Refusals and Opacities

4.2.1 | 4.2.2 | 4.2.3 | 4.2.4Digital and Ethical Workflows

4.3.1 | 4.3.2 | 4.3.3 | 4.3.4 | 4.3.5Conclusion

4.4.1Coda

Prometheus Undone

5.1.1 | 5.1.2 | 5.1.3 | 5.1.4Appendix

The Tuberculosis Corpus

X.1.1 | X.1.2 | X.1.3Web Design

X.2.1 | X.2.2 | X.2.3 | X.2.4Installation Materials

X.3.1 | X.3.2 | X.3.3Index

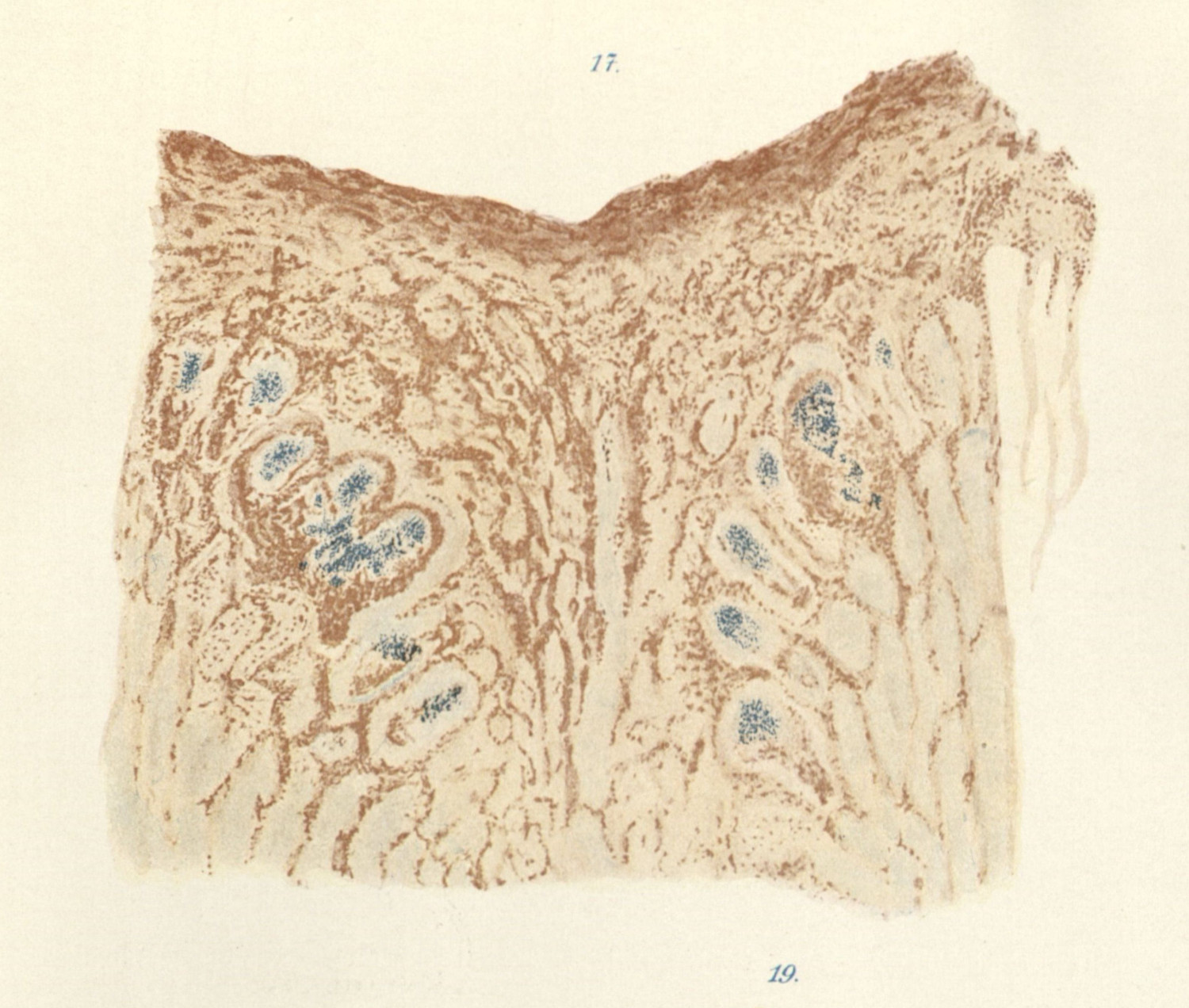

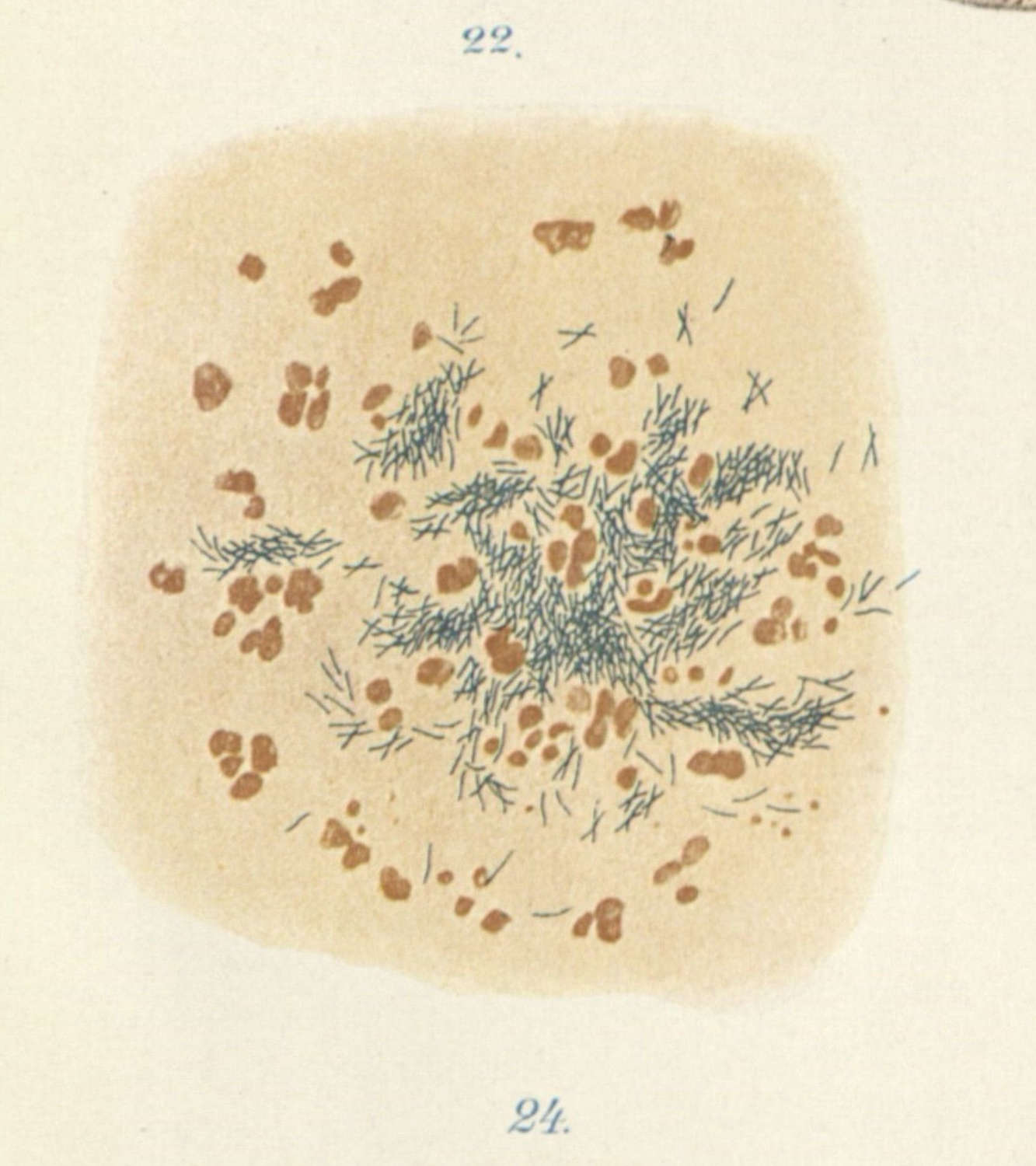

Koch made the transmissions of bacteria between research animals visible through the application of chemical dyes. The dying process, with its specialized labor and its reliance on relatively new chemical compounds, resulted in a research object that appeared legible to the discerning gaze of the German academy. Where Koch’s postulates stressed a logical framework to understand the presence of a bacterium in a sample, this theoretical framework elides the material labor which was required to display the presence of the germ: it had to be cultured, maintained in live animals,1 passed between animals and cultures, and then made visible to the most skeptical of observers. For this section I will go into detail as to the material and chemical interactions which enable Koch’s arguments to be seen, with specific care to outline Koch’s staining process.

To stain a tuberculous sample, Koch took a small, thin piece of tissue extracted from a test animal—either extracted from an animal presenting with tuberculosis of the eye, or taken from their lungs at autopsy—and pressed it against a glass slide. Koch was most interested in the tubercle—the hardened mass that is emblematic of a tuberculosis infection (2.2.2)—and would crush this growth onto the glass of a slide or petrie dish. This segment was dried, and then gently heated by carefully passing the slide over a bunsen burner three times.2

The coloring mixture contained 100 milliliters of aniline water, 11 milliliters of alcoholic methyl violet or fuchsine, and 10 milliliters of absolute alcohol.3 The specimen was submerged in this solution for twelve hours and following this bath it was washed with diluted nitric acid, washed again with a 60% alcohol solution, and colored again using a diluted vesuvian solution or methylene blue. The slides were finally washed in alcohol, brightened with cedar oil, and encased in Canada balsam.4

This whole process takes advantage of a property of a specific strain of bacteria known as acid-fast bacteria (AFB). These microorganisms, which fit under the genuses Mycobacterium and Nocardia, include tuberculosis and leprosy, and they are resistant to decoloration by acid, meaning that they keep the original shade that they are dyed in the first twelve-hour soak. Koch’s process first stained the entire sample the same color, and then used acid to wash away any dyes in the cells that lack the acid-fast property. After this process, what was left was the strikingly contrasting cells of Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

What is significant for Koch, and for my argument, is that on top of this chemical process, there was an aesthetic process. Making Mycobacterium tuberculosis real for his scientific audience meant making it contrast with the other objects in the microscopic frame. Koch writes this multiple times in his essay, but an exceptional example can be found in his section on staining:

Even in the closest masses of grains and in the midst of broken down cells, which often take all possible forms, from the smallest little points and micrococci like forms, to the longish staff-like forms, one can with absolute certainty distinguish single tuberculous bacilli from these closely similar forms by means of their dark blue color, which in the brown-colored surrounding and owing to the light-absorbing power of the brown ground appear as staffs almost colored black.5

Koch’s language was one of isolation through contrast: the bacterium’s figure appears in such a way as to frame itself, to make itself known to the discerning gaze of the viewer. Koch writes, a few pages later, that “[t]he bacilli do not show themselves in their full number until after their coloring: they may be distinguished not only on the thinnest spots of the preparation, but everywhere with full certainty, even among the thick heaps of cells.”6 Staining makes sense of a noisy frame, making the presence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis legible in a stark and obvious way. The argument becomes simple because it is seen, and it becomes impossible, for the anti-germ scientists in the room, to refute it.

I use this case study to point to a kind of visual rhetoric which was present in Robert Koch’s research (1.1.2; 2.2.2). Koch provided the method for producing multiple potential stains—methyl violet or fuchsine for the first bath, and vesuvian solution or methylene blue for the second rinse—as he was already thinking about the different visual compositions of different samples:

In order to obtain as striking a contrast as possible, between the coloring of the bacilli and the cell-grains, a yellow or light brown is chosen for the supplementary coloring material when the bacilli are blue; a green or blue is chosen when they are red.7

Koch notes, in developing these staining methods, that he was unable to image the bacteria using microphotography, which he had developed in his previous work on anthrax. The attention and detail in the staining process was always leveraged toward what would be most legible to the human observer.

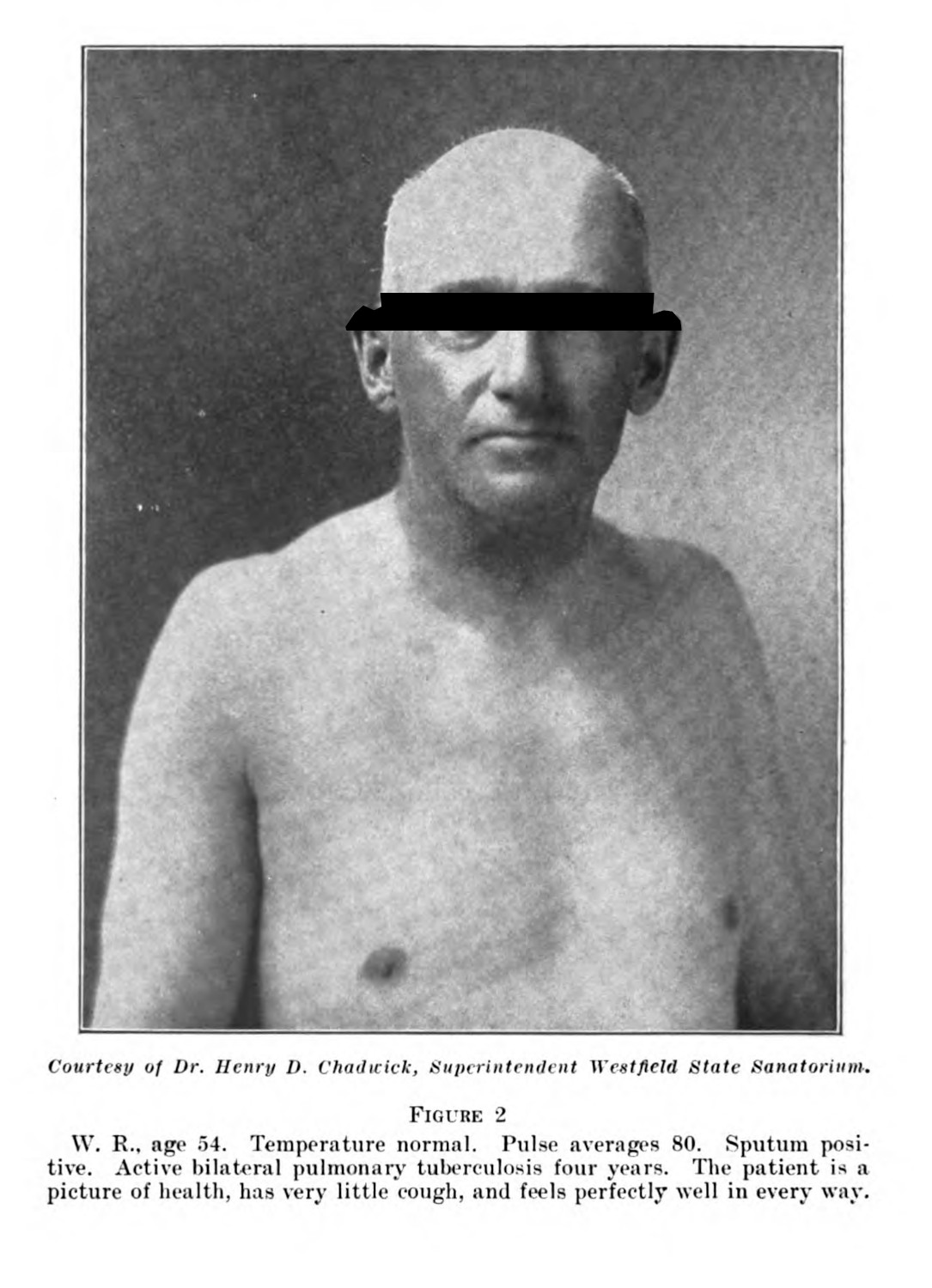

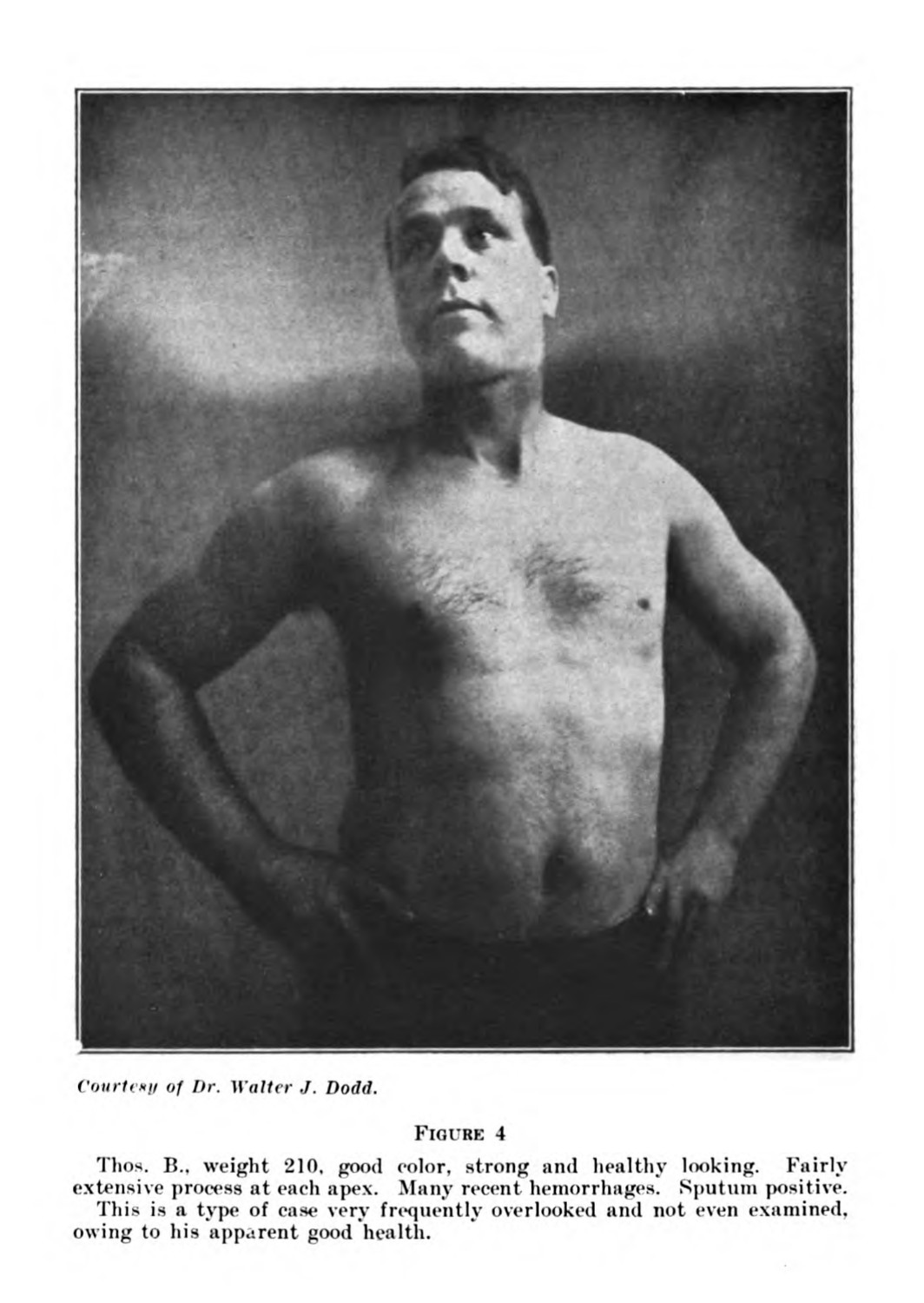

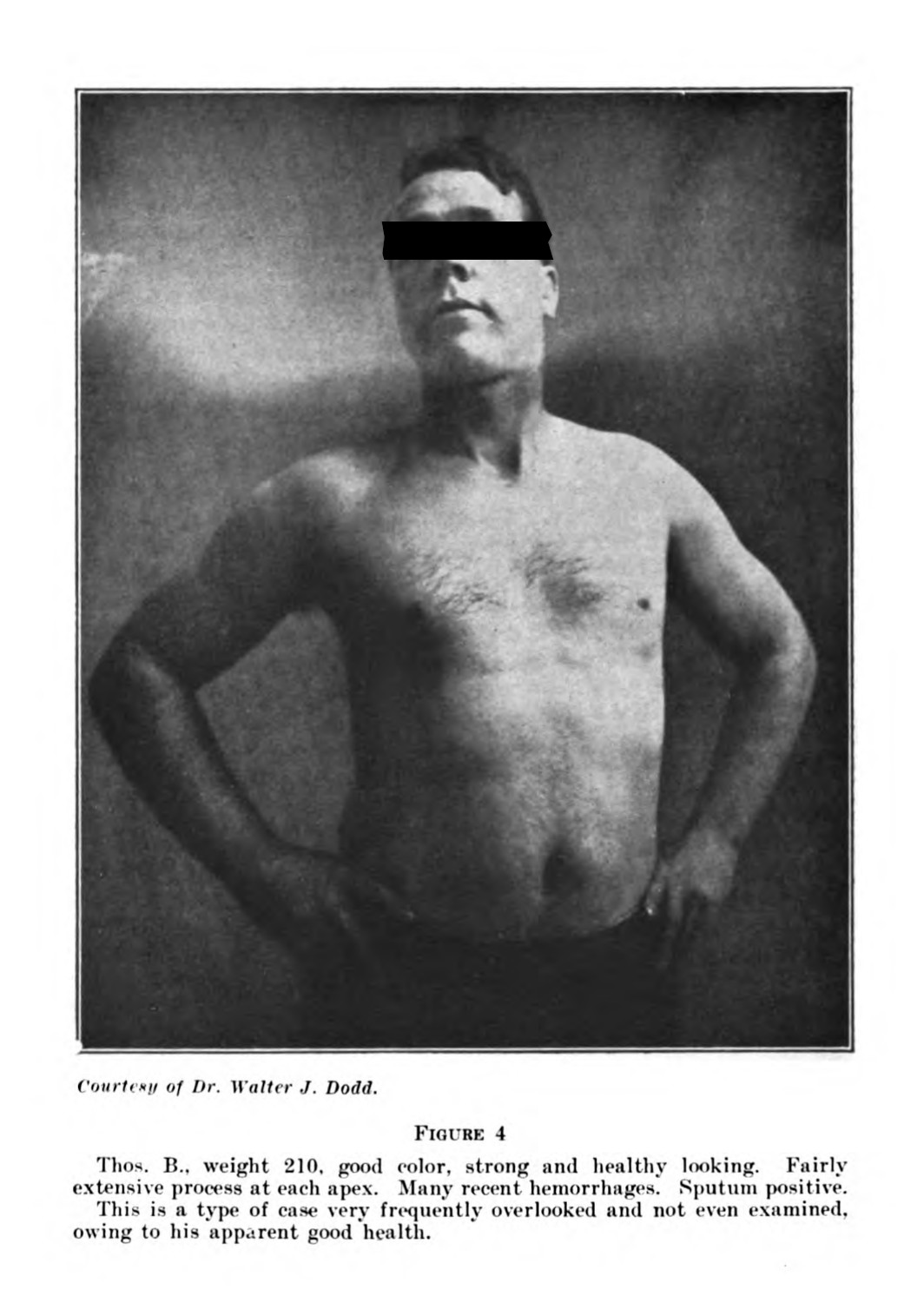

Prior to the use of x-rays in diagnosis, which would become common in the 1920s and after, doctors relied on a sputum test, which used a histochemical process to look for tuberculosis in expectorated pleghm. Sanatoria used the presence of a lab as a selling point to the validity and modernity of their facilities (1.2.3). Koch’s visual argument shifted from the presence of tuberculosis as a germ to the presence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in the body of a given patient. The histological and histochemical process changed how doctors understood and addressed maladies in the human body, and altered how doctors looked at and treated patients with tuberculosis. The clinical gaze was, in the context of a sputum test, not a practice of authority, but something that had to be verified through biochemical examination—a gaze which itself required specific, but different, kinds of training (figs. 3 - 5) (1.1.2; 2.2.2).8 Koch’s work created new understandings for the study of tuberculosis, but it also enshrined these specialized gazes, the technologies associated with them, and the practices that would be employed by medical scientists in the decades and century to follow.

-

Edward Livingston Trudeau notes how difficult it was to raise guinea pigs in the Adirondacks. He eventually settled on rabbits for his experiments, because they could survive winter in upstate New York.

Trudeau, Edward Livingston. An Autobiography. Garden City & New York: Doubleday, Doran & Company, Inc., 1944. ↩

-

Koch, Robert. Aetiology of Tuberculosis. Translated by T. Saure. Transactions of the Massachusetts Medical Association. New York: William R. Jenkins, 1890. 13. ↩

-

Koch’s units relied on cubic centimeters, which translate to milliliters. ↩

-

Koch, Robert. Aetiology of Tuberculosis. 13. ↩

-

Koch, Robert. Aetiology of Tuberculosis. Translated by T. Saure. Transactions of the Massachusetts Medical Association. New York: William R. Jenkins, 1890. 14. ↩

-

Ibid., 18. ↩

-

Ibid., 12. ↩

-

Curtis, Scott. “Photography and Medical Observation.” In The Educated Eye, edited by Nancy Anderson and Michael R. Dietrich, 68–93. Hanover: Dartmoth College Press, 2016. ↩