Introduction

Specimen Studies

0.1.1 | 0.1.2 | 0.1.3 | 0.1.4 | 0.1.5Methods

0.2.1 | 0.2.2The Structure of this Dissertation

0.3.1Tuberculosis' Visual Culture

Visual Practices in Medical Culture

1.1.1 | 1.1.2 | 1.1.3Seeing and Settling in the Sanatorium Movement

1.2.1 | 1.2.2 | 1.2.3 | 1.2.4 | 1.2.5Teaching Public Health

1.3.1 | 1.3.2 | 1.3.3 | 1.3.4 | 1.3.5Representing Doctors in Tuberculous Contexts

1.4.1 | 1.4.2Using Human Specimens in the Study of Tuberculosis

Seeing Disease in Methyl Violet

2.1.1 | 2.1.2 | 2.1.3 | 2.1.4Case Histories

2.2.1 | 2.2.2 | 2.2.3 | 2.2.4Visceral Processes

2.3.1 | 2.3.2Relation

2.4.1 | 2.4.2 | 2.4.3Arts-Based Inquiry

Introduction

3.1.1 | 3.1.2 | 3.1.3 | 3.1.4Terminal Imaginaries & Tuberculous Imaginaries

3.2.1 | 3.2.2 | 3.2.3 | 3.2.4 | 3.2.5 | 3.2.6Dermographic Opacities

3.3.1 | 3.3.2 | 3.3.3 | 3.3.4Tactical Pretensions

3.4.1 | 3.4.2 | 3.4.3Designing Opacity

A Shift towards the Anticolonial

4.1.1 | 4.1.2 | 4.1.3 | 4.1.4Refusals and Opacities

4.2.1 | 4.2.2 | 4.2.3 | 4.2.4Digital and Ethical Workflows

4.3.1 | 4.3.2 | 4.3.3 | 4.3.4 | 4.3.5Conclusion

4.4.1Coda

Prometheus Undone

5.1.1 | 5.1.2 | 5.1.3 | 5.1.4Appendix

The Tuberculosis Corpus

X.1.1 | X.1.2 | X.1.3Web Design

X.2.1 | X.2.2 | X.2.3 | X.2.4Installation Materials

X.3.1 | X.3.2 | X.3.3Index

The term clinical vision refers to a mode of seeing which is trained in doctors. An influential critique of medical epistemics and its entanglement with the field’s curative practices, the term was described in The Birth of the Clinic as a part of a sociotechnical shift in the history of medicine, born out of post-revolutionary France. The clinical gaze was the result of a number of entwined shifts in medical science and diagnostic practice. Doctors began to look at the bodies of patients in aggregate, tracking symptom progression in multiple subjects with the same afflictions. This causal linkage between similar symptoms was supported by posthumous observation, whereby a patient was autopsied following their death to inspect organs for aberrant formations or differences from the “normal” conception of that organ.1

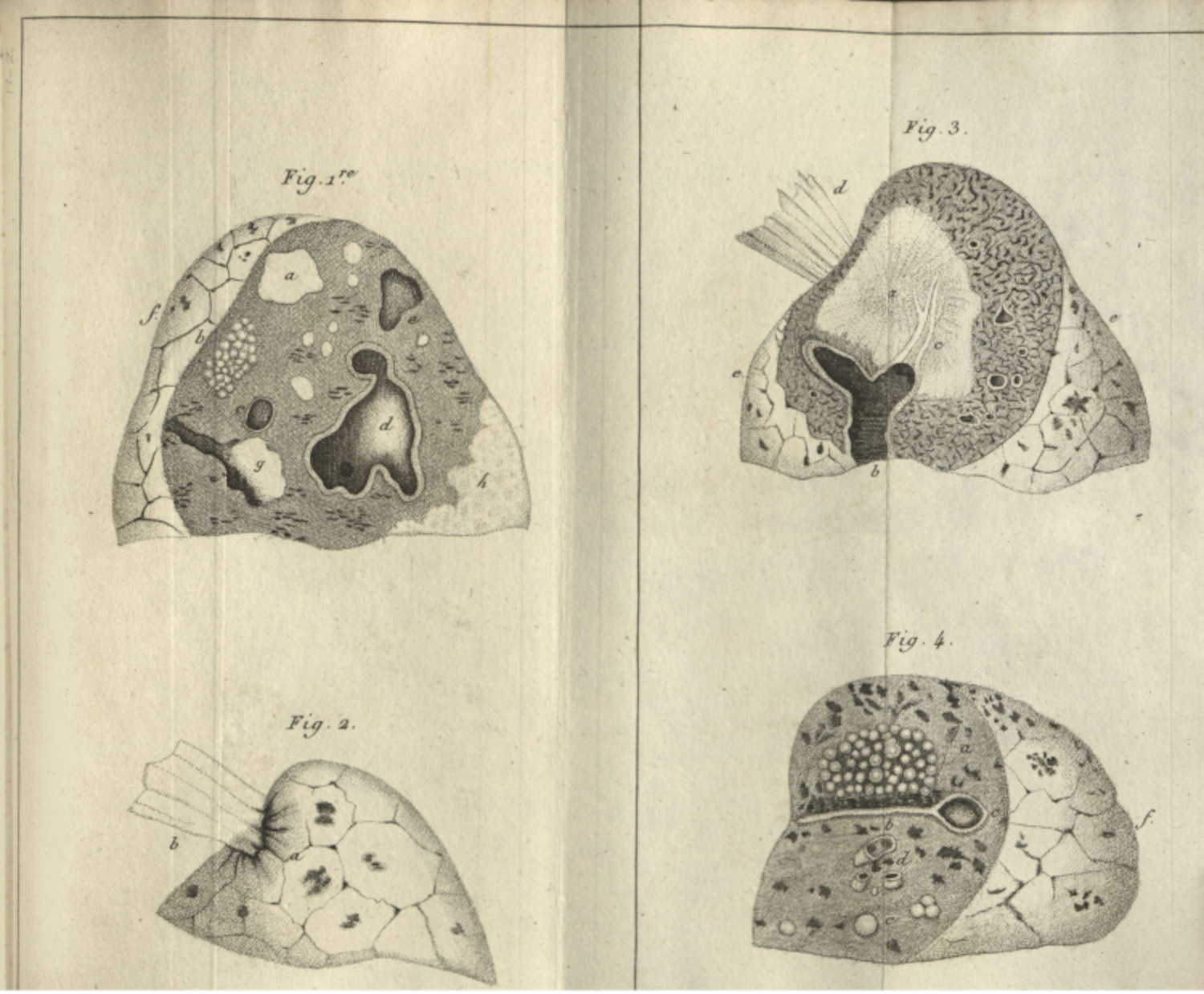

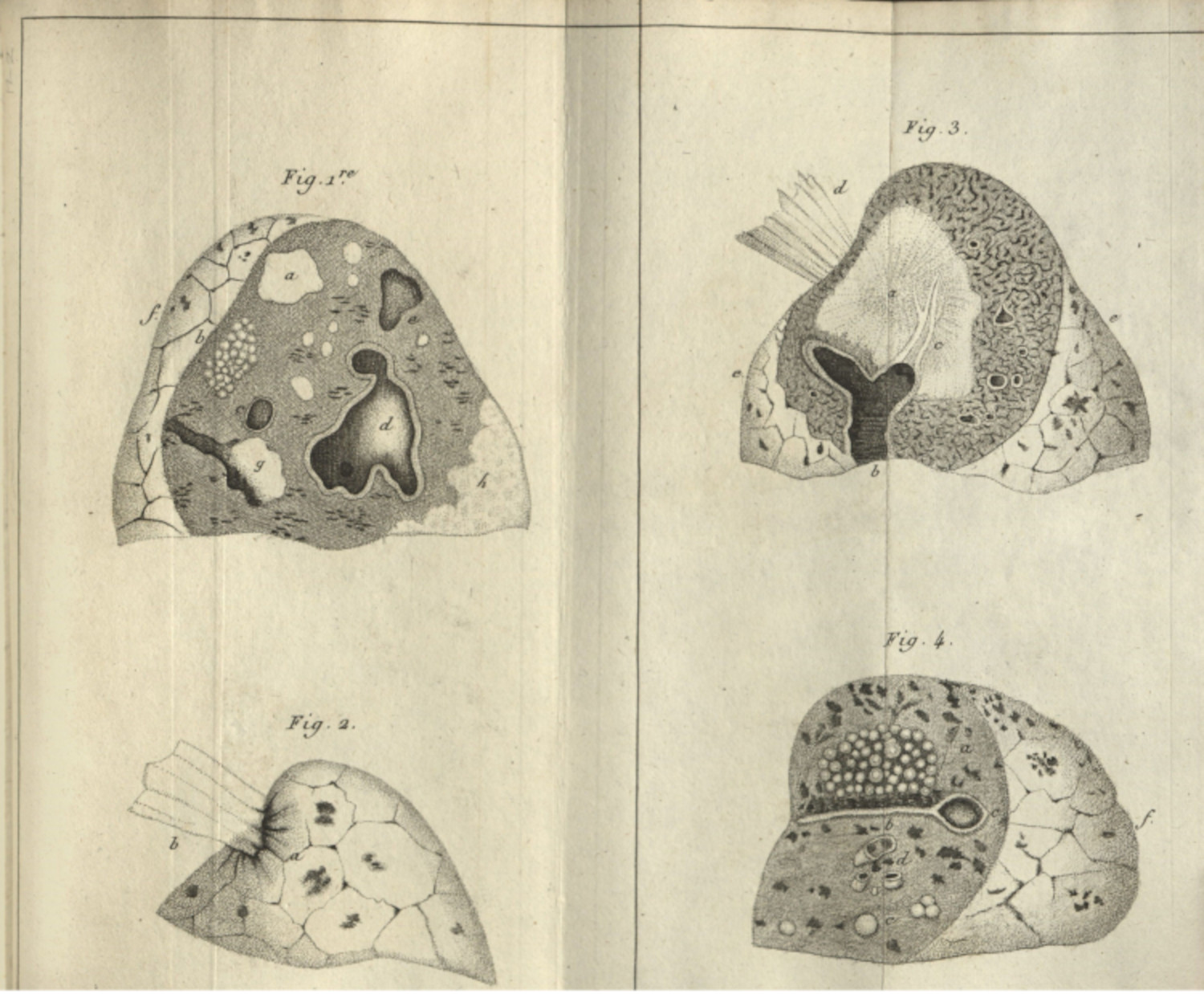

This clinical method is best exemplified in the work of René Theophile Hyacinthe Laënnec. The French doctor used these same methods to link the tubercle—a small hardened mass the size of millet that would form in the lungs of patients with tuberculosis—to phthisis, or consumption (fig. 1). Viewing patients at the Hôspital Neker and diagnosing them with consumption, Laënnec then autopsied the patient’s body after their death, looking for aberrations in normal anatomy that might be linked to the symptoms the doctor observed. Finding these hardened masses in the lungs of his consumptive patients, and not in patients who had died of other conditions, the French doctor was able to convincingly argue the relationship between the tubercle and consumption.2

This emphasis on disease through symptom-focused analysis and its relation to anatomy creates an epistemic problem: in order to see disease, doctors would need to project onto a patient’s body what the doctors assumed to be a “normal” anatomical body. To create disease, medicine first needed to imagine an idealized human subject,3 and then use that figure to see contrasts on the body of the patient. Important for this mode of vision is an implicit dehumanization of the sick patient: the doctor is not trained to see the patient, but the disease as it manifests in their body. The problem of the clinical gaze is that sickness is always construed as abnormal and it is always defined from and through the bodies of the sick, dead and dying.

More contemporary scholars have engaged with medical vision to describe how different technologies have expanded upon or complicated Foucault’s original concept. In media studies, scholars like Catherine Waldby and Jose van Djick have described how clinical vision is linked to technologies of transparency, which reveal the insides of the opaque body. Responding to x-ray, MRI, and other penetrative visual technologies, van Djick notes the continual quest for transparency as an epistemic ideal; she describes an ideology in medicine that idealizes perfect, penetrative vision as a mode to better diagnoses and disease treatments.4 This transparency also becomes an aesthetic within which more perfect anatomies can be made. Waldby, criticizing the Virtual Human Project from the 1990s, describes the construction of a supposedly perfect anatomical dataset, through digital scanning, photography, and the slow destruction and liquification of two human subjects, one male and one female.5 For these two scholars, technology extends and refines Foucault’s ocular practices: always creating more avenues to see difference and more perfect representations of supposedly “normal” human anatomy.

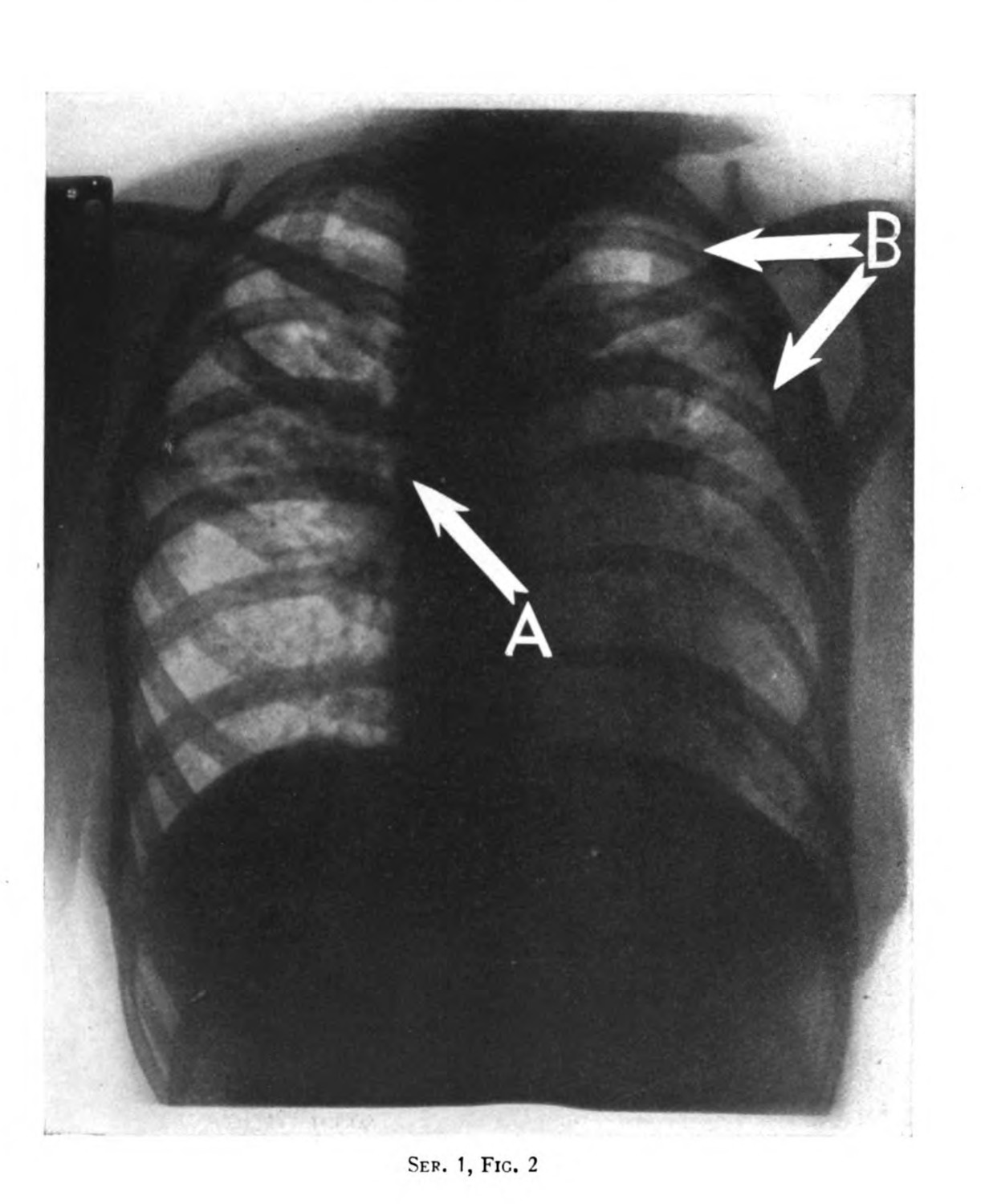

At the turn of the twentieth century, these modes of transparency were just developing. Wilhelm Röntgen had only started to demonstrate the use of radiation in viewing the human body; x-rays would become a key diagnostic practice for future tuberculosis workers, but this would take decades of experimentation before standards would be developed.6 Photography was still being experimented with as a potential practice for medical research and diagnosis. Erin O’Connor describes the use of photography to catalog and reproduce rare pathologies for the use of lay doctors at the turn of the twentieth century. The technology of the photograph extended clinical vision in ways that better trained doctors in the period.7 It became a medium that encouraged and expanded scientific collection practices,8 which conceived of creating an exhaustive archive of potential maladies, pathologies, and embodied symptoms.9 Photography, and later film, helped study specific phenomena which these media could easily capture.

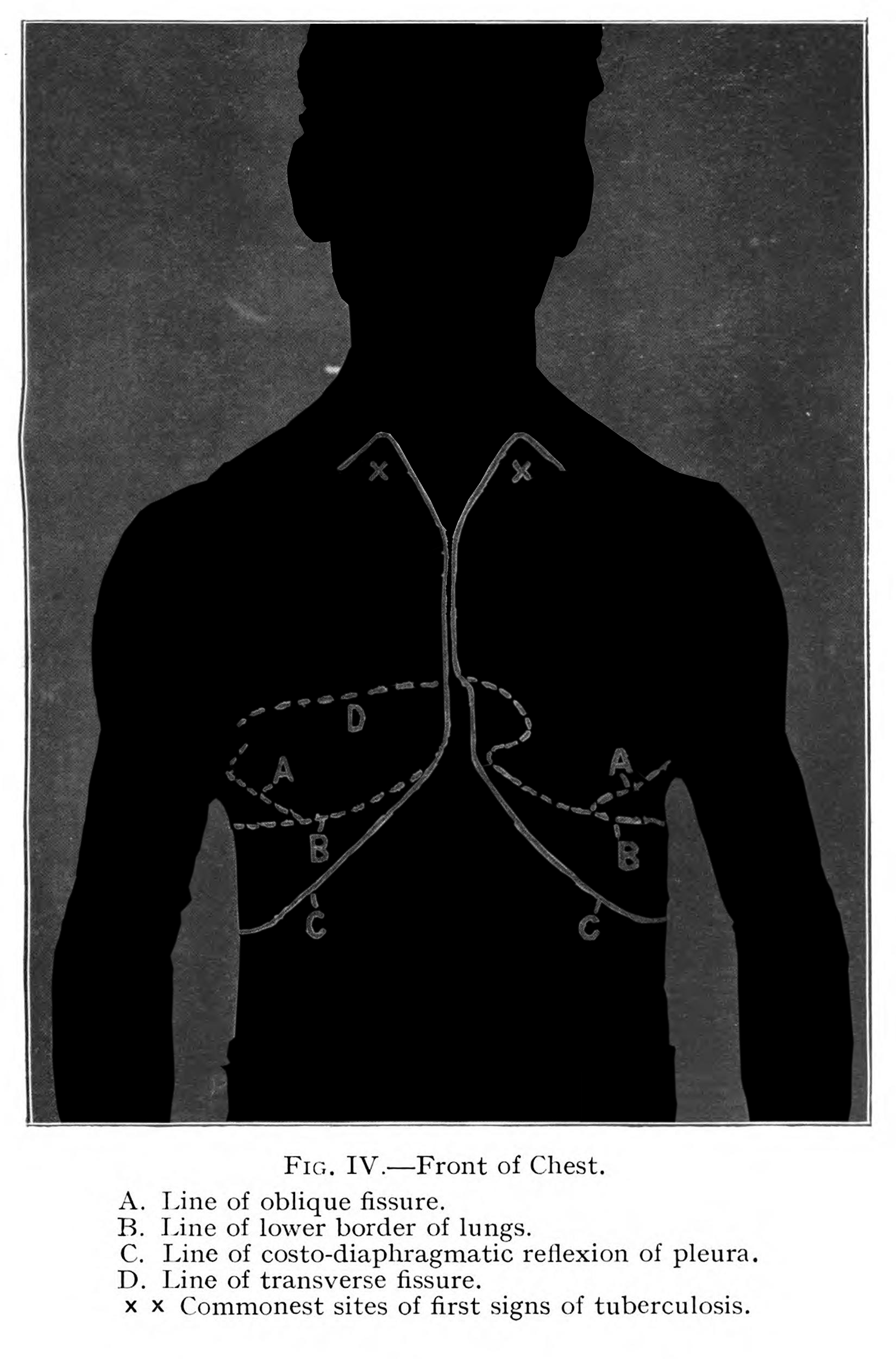

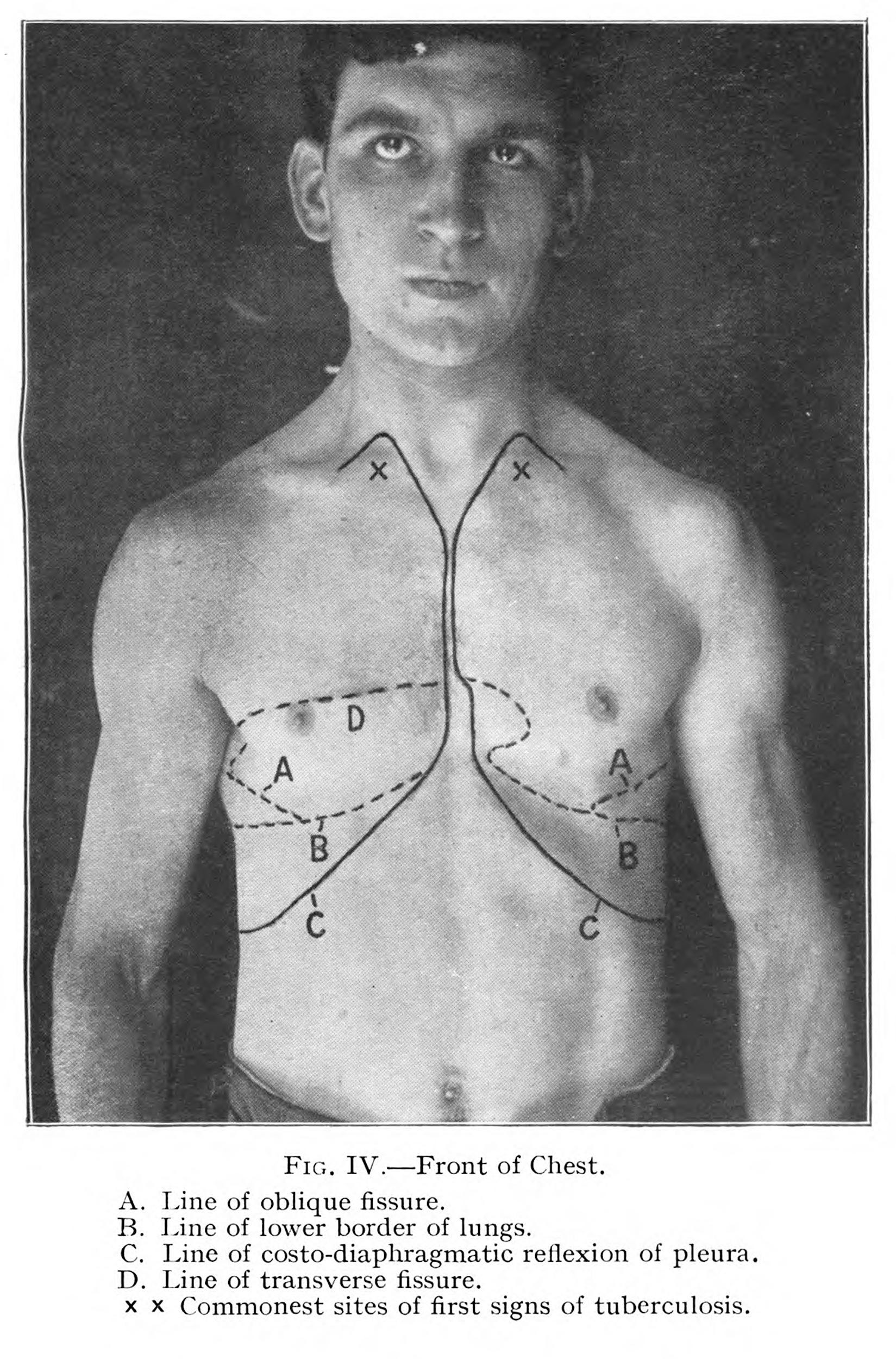

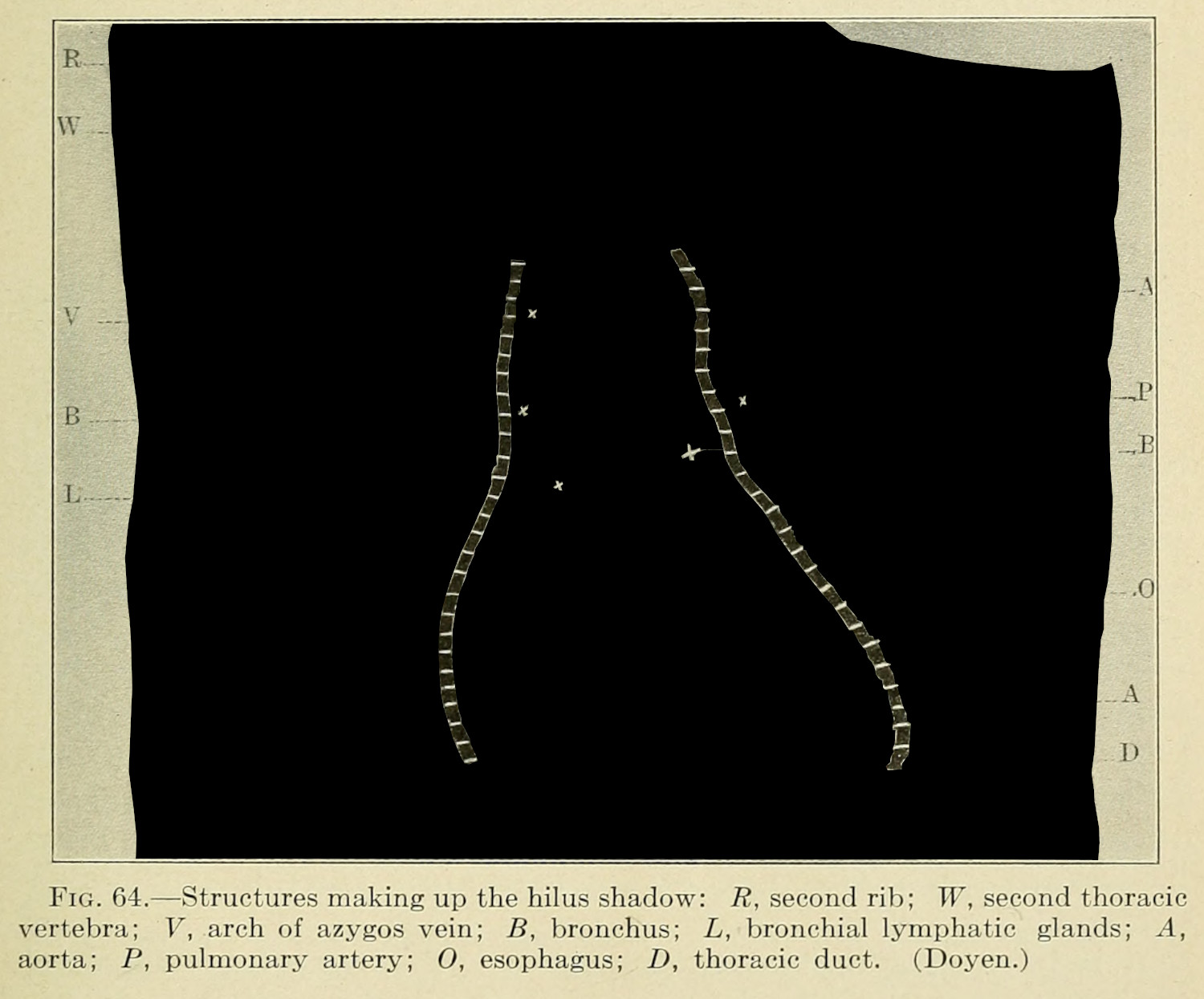

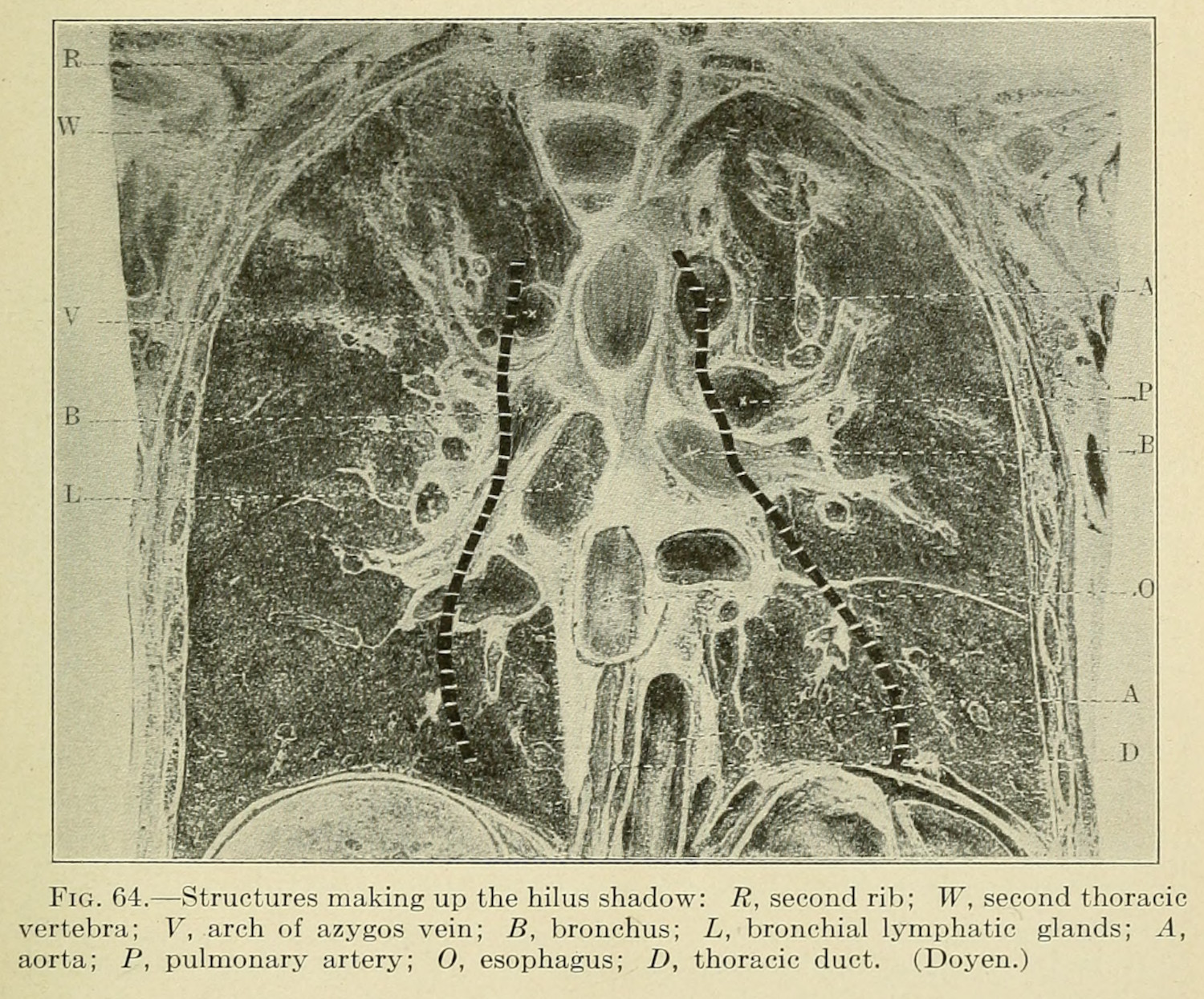

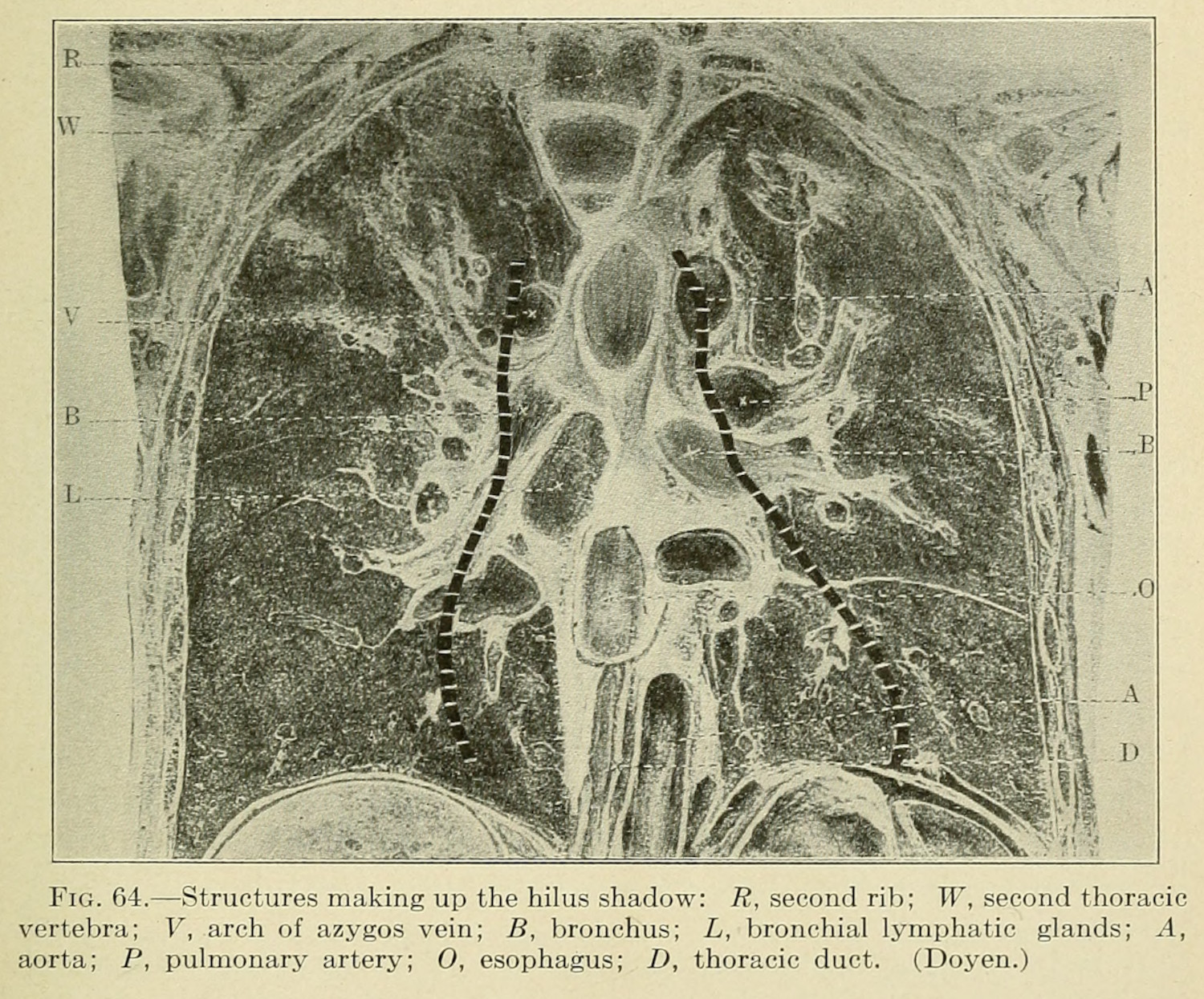

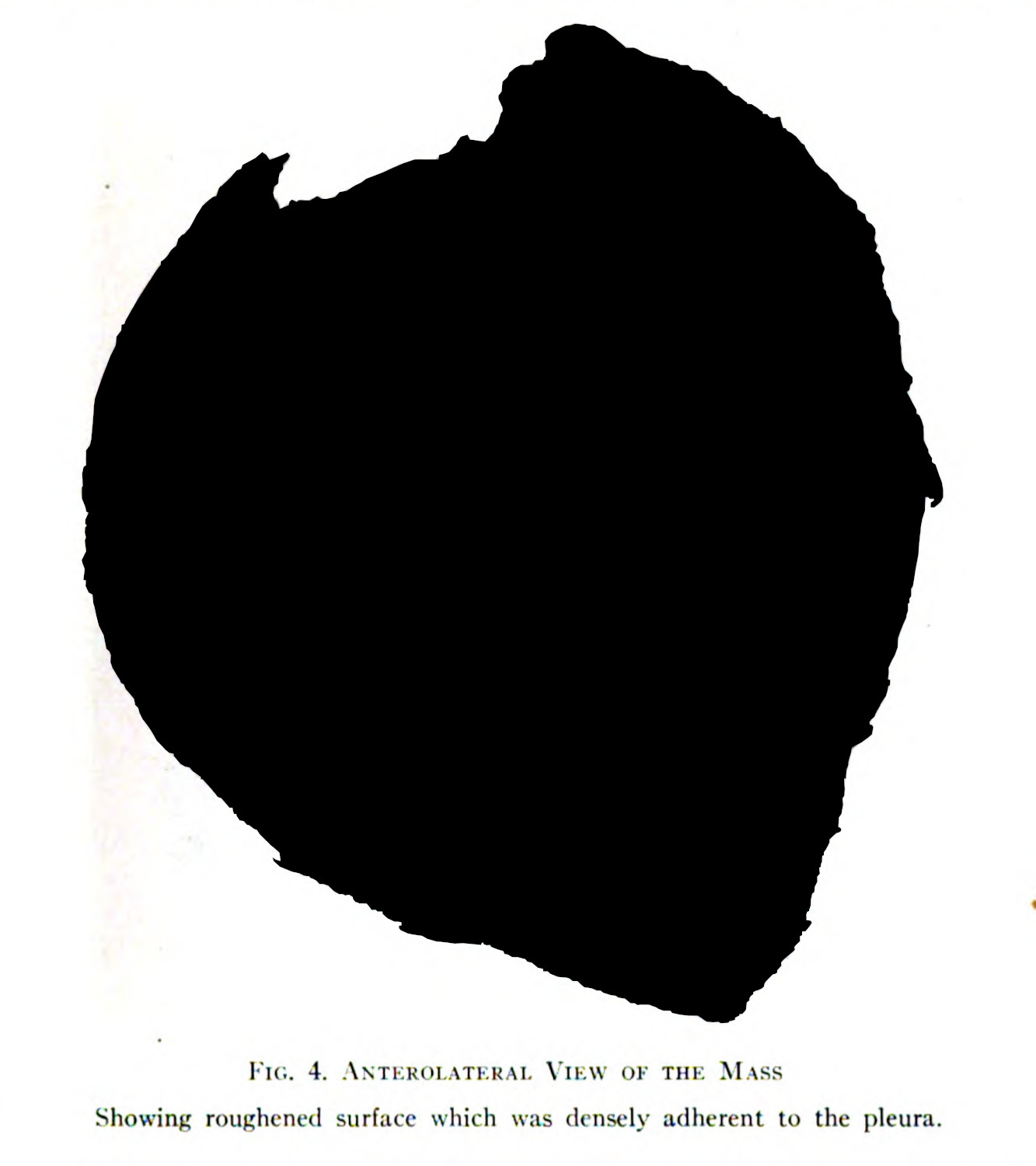

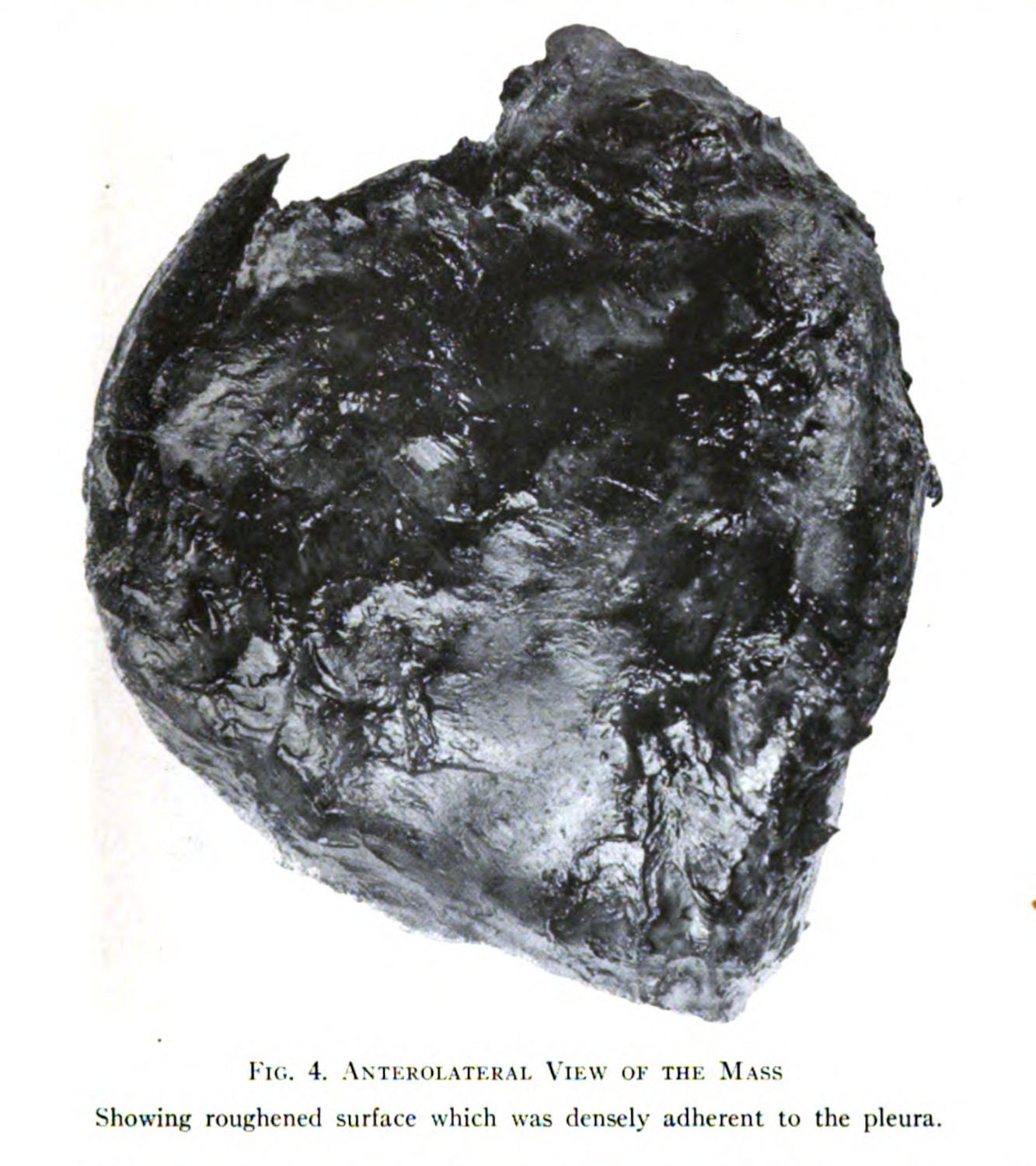

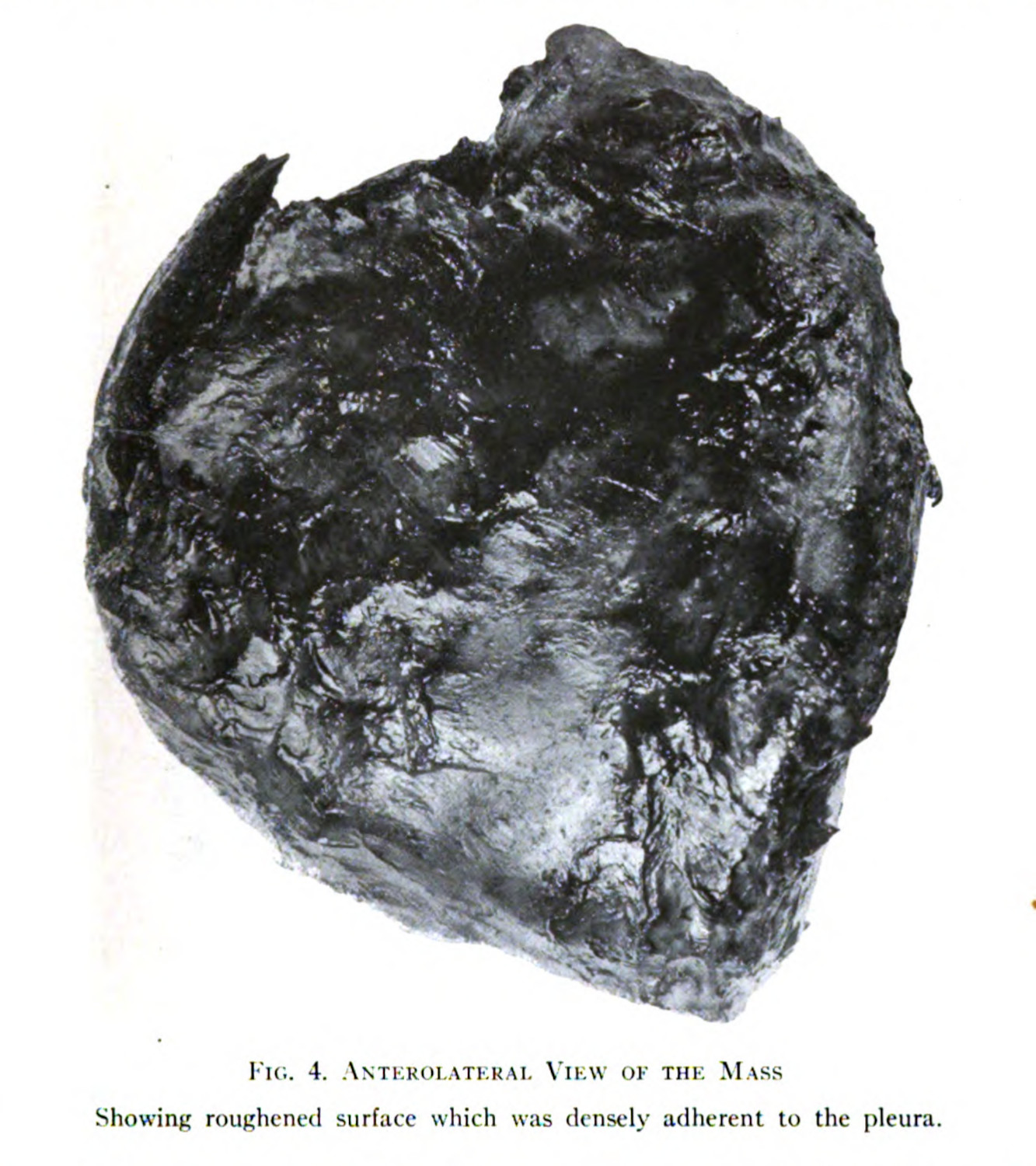

One limitation for these scholars is an overcommitment to Foucault’s clinical vision. The clinical gaze is trained and evoked in various practices and technologies, but it is not the only ocular practice at play in medical science and medical culture (1.1.2). Scott Curtis, who has researched medical film in Germany at the turn of the twentieth century, provides two useful frameworks to extend and complicate medicine’s visualities. First, the visual training employed in medical education was not just an alienating mode of seeing the patient, it was also constructed as a way to maintain epistemic and cultural superiority. Doctors were trained to see the natural, as it was constructed for them through various media, from film, to photograph (fig. 2), to wet specimen (fig. 4), to x-ray (fig. 3), to stained histological samples (1.1.3). Curtis writes, “[t]he ‘objectivity’ of the scientific eye arose not merely out of professionalization but also in contrast to the ‘subjectivity’ of the untrained other. That is, disciplinary modes of viewing relied on class distinctions, as well as professional training.”10 The ability to read these images, obdurate and unyielding as they are, within the discourses already established, produced a means to distinguish medical doctors as experts and make clinical training valuable.

Second, in addition to this ocular professionalization, there are certain practices that co-opt and control technologies for biomedical research. Curtis also argues that it is not just the doctor who is trained in particular ways, the patient and the measuring apparatuses must be trained as well.11 For photographic representations of disease, patients had to be held still (1.4.2), and different technologies, like microphotography or histochemistry, had to be developed and evoked (2.1.1; 2.1.3).

These robust visual models provide helpful frameworks to think about medical vision; however, these modes of seeing, training, and making visible, depend on a top-down framework. They ask, what did the doctors want to see? How did they want to see it? And how did they make their visions possible? These are certainly questions I am trying to answer, but I want to add a secondary layer of analysis: How did these representational methods and frameworks produce value for researchers in their fields? How did these representations get made from the bodies of patients (2.2.4; 2.3.1)? How did the patient’s lived experience, and embodied history, become central in the articulation of biomedical claims (2.2.3)? Importantly, the patient is a crucial interlocutor in this analysis, as all of these questions have to be asked using their bodies, their histories, and their remains (2.1.4; 2.2.3; 2.2.4).

I describe representation in these questions to connect the concerns with visual culture and new materialism to media studies and science and technology studies (STS). I evoke different theoretical frames to stress that 1) specimens are an extractive technology that depend on patients; 2) specimens are a representational technology to convey arguments in the medical sciences (0.1.3); and 3) that media studies is uniquely equipped to navigate the ideological, cultural, historical, and epistemic problems which undergird medical research.12

I stress that the specimens are not literal manifestations of disease, but that they are images that can be understood as representing a disease to a trained medical professional (0.1.3).13 These are inscriptions—the written documents that form the backbone of scientific labor14—which are made through the exquisite and intricate mounting for a camera, for a microphotographic apparatus, for an illustrator, or for an x-ray (2.2.1). Following Bruno Latour, these visual objects are staged:

What we are really dealing with is the staging of a scenography in which attention is focused on one set of dramatized inscriptions. The setting works like a giant optical device that creates a new laboratory, a new type of vision, and a new phenomenon to look at.15

The representational practices which were developed, in the case of histochemistry (2.1.3), or deployed, in wet tissue specimens (2.2.1; 2.3.1), were done so in a context where they would be believed without needing additional discursive training. Fundamentally, the images as they appear in this chapter never had to exist as they do, because the scientific believability of these images is tied less to the object displayed so much as the manner and context that they were made. While Latour framed his discussion of representation in science in the metaphor of war—conscription, reinforcement, victory16—I argue that these practices were also moments of discursive value. Value, as I use it, corresponds to something of worth that can be leveraged with, borrowed on, or capitalized upon, which is accrued in the context of social capital,17 but which is also something that confers a kind of material wealth (0.1.4).

An important limitation in Latour’s representational framework, and early STS assumptions of scientific argument, is that they tend to evacuate the natural to focus entirely on the constructedness of scientific argument. The field has a long history attending to this issue, with Latour himself being central in the development of ontologies that consider the non-human in the production of human cultures (2.4.1; 2.4.2).18 My emphasis on the specimen as a representational practice is meant to focus on the social construction of the medical research object, while also being cognizant of its necessary linkage as an index to a real phenomenon, from a real, living person (2.2.3; 2.2.4; 2.4.2).

I use the term “index” to evoke the work Roland Barthes and his emotive reading of photography. His book, Camera Lucida, while being a meditation on photography, spends a lot of time reflecting on death. The back half of the deeply personal monograph looks to a photograph of Barthes’ recently deceased mother, a photograph that had been taken when she was young. For Barthes, and only Barthes, the photograph is important, because it depicts a figure of someone who is lost, and signals the grief that erupts in the process of mourning. Photographs, for the French philosopher, are inherently tragic, because they carry with them an inevitability. They imagine people in such a way as to also, necessarily, refer to their death.

Reflecting on an 1865 photograph of Lewis Payne, a would-be assassin, taken by Alexander Gardener right before Payne’s hanging, Bathes writes

The photograph is handsome, as is the boy: that is the studium. But the punctum is: he is going to die. I read this at the same time: This will be and this has been; I observe with horror an anterior future of which death is at stake. . . . Whether or not the subject is already dead, every photograph is this catastrophe.19

Barthes’ reading of photographs is an empathic one, driven by the impossibility of the image. He spends a great deal of time in the book wrestling with the hermeneutics of the photograph, coming to a model of analysis: The studium refers to the everyday interest in what a photograph might show, and the way they may be studied, which contrasts with the prick or punctum which stirs an excitement, engagement, or eroticism of a few unique images.20 The academic engagement with this technology is at a loss when what is imaged becomes personal and Barthes is enveloped in grief.

I go to Barthes because of how important mourning is in his understanding of photographs, and how absent mourning is in the any of the discourses described in this chapter. Photographs of organs are a strange thing because in many cases they fall outside the future as death problem which plagues the subjects of Barthes’ analysis (fig. 5). Many of these organs were most likely taken from dead subjects. While I could point my finger to this gap in Barthes’ theoretical framework, note its deficit, and proclaim a new, improved model, I want to instead trace back the empathic origins of his study, and loop them into a different understanding of these images. The catastrophe of photography is a result of its index of life and the recognition of an other who has lived, and who has already died or will die in time.

I want to use Barthes to propose a counter reading of the clinical image. While doctors were trained to view their research subjects in particular ways, and medical historians, health humanists, and medical media studies scholars are trained to understand and convey these historically, culturally, and discursively structured visual practices, we harm ourselves and our academic conversations by reducing our own viewing practices to only comprehend our research object; we become complicit in them (2.3.1; 4.3.4). Our analyses circumvent the most basic epistemic fact of medical knowledge: it depends on human subjects. Every image in this section was taken from someone, someone who was suffering from some disease, someone who had died from that malady or is dead now.

Published a decade after Camera Lucida ,Susan Sontag’s Regarding the Pain of Others examined the genre of refugee photos to untangle a similar problem. She asks why these images are so popular while also not resulting in any meaningful political change, articulating a metacritique of these photographs. There is a privilege which is exposed when a subject’s suffering is made into an object. She writes,

To speak of reality becoming a spectacle is a breathtaking provincialism. It universalizes the viewing habits of a small, educated population living in the rich part of the world, where news has been converted into entertainment—that mature style of viewing which is a prime acquisition of ‘the modern,’ and a prerequisite for dismantling traditional forms of party-based politics that offer real disagreement and debate. It assumes that everyone is a spectator. It suggests, perversely, unseriously, that there is no real suffering in the world.21

Sontag notes the privilege of viewing suffering, of seeing it while flipping through a newspaper or magazine, of nonchalantly consuming it. I would be doing harm if I were to do the same with the broad, distanced perspective which populate the tuberculosis corpus and image data set (X.1.1; X.1.3).

Specimen photographs are portraits: portraits of disease, but this is a smaller part of what they are. Specimen photographs are indexes of people: people who lived and died and whose afterlife is caught in medical journals. This reality is both denied in the visual practices which produce and reproduce these objects, and in the context of Foucauldian clinical vision, they are inexorably connected to their epistemic value.

This link is not just an epistemic one, for both Barthes and me, but it is also an ethical one. I am obligated, by my relation to these subjects, to tend and care for them (0.1.5; 2.4.3). I cannot separate myself from the person who lived, was sick, and died, because that separation is what produces the idea that the specimen is an object, and not a person, in the first place(0.1.4). Keeping the patient in view at every step is necessary for my analysis.

-

Foucault, Michel. The Birth of the Clinic: An Archeology of Medical Perception. Translated by A. M. Sheridan Smith. New York: Vintage Books, 1994. ↩

-

An interesting note here, is that Laënnec’s practices were not as visually dominated as Foucault would argue, as Laënnec was the projenitor of the stethoscope and the practice of asculculation as a method to diagnose tuberculosis.

Laënnec’s introduced the use of auscultation in diagnosis, as well as the auditory tool of the stethoscope; however, for the sake of this argument, my interest is particularly drawn by his use of postmortem analysis to make medical observations. ↩

-

The ramifications of this practice are myriad, and still impact the lives of individuals who do not fit within contemporary assumptions concerning the ideal (white, male) human subject. ↩

-

Dijck, José van. The Transparent Body: A Cultural Analysis of Medical Imaging. Seattle & London: University of Washington Press, 2005. ↩

-

Waldby, Catherine. The Visible Human Project: Informatic Bodies and Posthuman Medicine. London & New York: Routledge, 2000. ↩

-

National Tuberculosis Association. “Improvement in X-Ray Technique.” In 20 Years of Medical Research, 44–48. National Tuberculosis Association, 1943. ↩

-

O’Connor, Erin. “Camera Medica.” History of Photography 23, no. 3 (1999): 232–44. ↩

-

Tucker, Jennifer. Nature Exposed: Photography as Eyewitness in Victorian Science. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005. ↩

-

O’Connor, Erin. “Camera Medica.” ↩

-

Curtis, Scott. The Shape of Spectatorship: Art, Science, and Early Cinema in Germany. New York: Columbia University Press, 2015. 95. ↩

-

Curtis, Scott. The Shape of Spectatorship: Art, Science, and Early Cinema in Germany. New York: Columbia University Press, 2015. 37-44. ↩

-

The last of these concerns is what has kept me in media studies, as I have moved to a much more interdisciplinary framework. While media studies began in a trajectory of English turned film studies, its frameworks are much more mutable than only focusing on popular, industrial, image-based representational technologies.

I lean toward media archaeology partly because it blows apart the hierarchy of media technologies making the bespoke and mundane technologies equally interesting for scholarly analysis.

Huhtamo, Erkki, and Jussi Parikka, eds. Media Archaeology: Approaches, Applications, and Implications. Berkeley, Los Angeles & London: University of California Press, 2011; Parikka, Jussi. What Is Media Archaeology? Cambridge: Polity, 2012; Gitelman, Lisa. Paper Knowledge: Toward a Media History of Documents. Duke University Press, 2014; Ernst, Wolfgang. Digital Memory and the Archive. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2012. ↩

-

Lynch, Michael, and Steve Woolgar. “Introduction: Sociological Orientations to Representational Practice in Science.” In Representation in Scientific Practice, edited by Michael Lynch and Steve Woolgar. Cambridge & London: The MIT Press, 1990. 11. ↩

-

Latour, Bruno, and Steve Woolgar. Laboratory Life: The Construction of Scientific Facts. 2nd ed. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1986. ↩

-

Latour, Bruno. “Drawing Things Together.” In Representation in Scientific Practice, edited by Michael Lynch and Steve Woolgar, 19–68. Cambridge & London: The MIT Press, 1990. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Bourdieu, Pierre. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1984; Bourdieu, Pierre. The Field of Cultural Production: Essays on Art and Literature. New York: Columbia University Press, 1993. ↩

-

Latour, Bruno. “Agency at the Time of the Anthropocene.” New Literary History 45, no. 1 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1353/nlh.2014.0003; Latour, Bruno. “Drawing Things Together.” In Representation in Scientific Practice, edited by Michael Lynch and Steve Woolgar, 19–68. Cambridge & London: The MIT Press, 1990. ↩

-

Barthes, Roland. Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography. Translated by Richard Howard. New York: Hill and Wang, 1981. 96. ↩

-

Ibid. 25-27. ↩

-

Sontag, Susan. Regarding the Pain of Others. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2003. 110. ↩