Introduction

Specimen Studies

0.1.1 | 0.1.2 | 0.1.3 | 0.1.4 | 0.1.5Methods

0.2.1 | 0.2.2The Structure of this Dissertation

0.3.1Tuberculosis' Visual Culture

Visual Practices in Medical Culture

1.1.1 | 1.1.2 | 1.1.3Seeing and Settling in the Sanatorium Movement

1.2.1 | 1.2.2 | 1.2.3 | 1.2.4 | 1.2.5Teaching Public Health

1.3.1 | 1.3.2 | 1.3.3 | 1.3.4 | 1.3.5Representing Doctors in Tuberculous Contexts

1.4.1 | 1.4.2Using Human Specimens in the Study of Tuberculosis

Seeing Disease in Methyl Violet

2.1.1 | 2.1.2 | 2.1.3 | 2.1.4Case Histories

2.2.1 | 2.2.2 | 2.2.3 | 2.2.4Visceral Processes

2.3.1 | 2.3.2Relation

2.4.1 | 2.4.2 | 2.4.3Arts-Based Inquiry

Introduction

3.1.1 | 3.1.2 | 3.1.3 | 3.1.4Terminal Imaginaries & Tuberculous Imaginaries

3.2.1 | 3.2.2 | 3.2.3 | 3.2.4 | 3.2.5 | 3.2.6Dermographic Opacities

3.3.1 | 3.3.2 | 3.3.3 | 3.3.4Tactical Pretensions

3.4.1 | 3.4.2 | 3.4.3Designing Opacity

A Shift towards the Anticolonial

4.1.1 | 4.1.2 | 4.1.3 | 4.1.4Refusals and Opacities

4.2.1 | 4.2.2 | 4.2.3 | 4.2.4Digital and Ethical Workflows

4.3.1 | 4.3.2 | 4.3.3 | 4.3.4 | 4.3.5Conclusion

4.4.1Coda

Prometheus Undone

5.1.1 | 5.1.2 | 5.1.3 | 5.1.4Appendix

The Tuberculosis Corpus

X.1.1 | X.1.2 | X.1.3Web Design

X.2.1 | X.2.2 | X.2.3 | X.2.4Installation Materials

X.3.1 | X.3.2 | X.3.3Index

In stressing the necessary epistemic continuity between clinical history and the wet tissue specimen, I also attend to the political valences between the dying and the dead in medical research. Biomedical research depends on the continuity between living subject, their lives, and the index of their life, dying, and death as it explored at autopsy (2.2.2; 2.2.3). The relationship that medical scientists have to their subjects is framed by an overarching discursive and cultural understanding of death—its death culture.1

This concept is borrowed from death studies, an interdisciplinary field that examines various human relationships with death. Scholars in this academic conversation have thought about how medical systems both frame and produce death for human subjects. Some of the most formative scholarship in this field, like the work of Phillipe Ariés, Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, and Cicely Saunders, has criticized the medicalization of death.2 Central in these scholars’ critique is that the institutionalization of death by medical actors leads to both homogenized experiences of death—which undermines the value and ritual of death in certain cultures and contexts—as well as the alienation of patients in hospitals.3 Ariés, the historian of this group of scholars, argues that in the twentieth century medically-mediated deaths became the dominant mode by which western individuals experienced the end of their lives, which overshadowed other cultural understandings concerning death.4

There are two limitations to the way death studies has engaged with the medicalization of death. First, is that by critiquing this practice, there is less emphasis on how and why subjects became medicalized in the first place. A subject who is dying of lung cancer in hospice may experience a good death,5 but their death may have been impacted by broader industrial malfeasance regarding air pollution and tobacco use. There is a continuity between the social, political, and structural forces outside of the hospital which need attention. Second, the emphasis on human death and its experience circumvents the more prominent role death factors into the creation of culture at large (2.1.4).6 Death is an inescapable interlocutor in the maintenance of life, and in the context of modern, western culture, death proliferates for humans and non-humans alike at a global scale.7 Death culture cannot and should not be isolated to the medical or human contexts. As I have written elsewhere, “What is key here is who and what dies, for whom and for what purpose do they die and who and what survives.”8

I adopt this turn to critique a form of necropolitics articulated by death scholar John Troyer. While other parts of Troyer’s scholarship are exceptional, his redefinition of Achille Mbembe’s necropolitics circumvents and ignores the Cameroonian postcolonialist thinker’s highly influential use of the term. Troyer writes, in a footnote, that Mbembe’s necropolitics is defined “as a politics of death. Necropolitics is more accurately, I argue, a political field that involves not the act of death itself but instead the already dead.”9 By making a semantic argument, Troyer neglects to engage with Mbembe’s definition of necropolitics—the structural ways the death of unwanted populations is built into a society, and the technologies that produce death at higher rates for those same populations.10

Mbembe’s necropolitics is an extremely helpful framework to discuss inequities in health especially, as it is a way to explain the huge losses of life by gay men in the AIDS epidemic or the current problem regarding the Black maternal death rate. While I chastise Troyer for undermining a prominent postcolonial theorist, I must also admit that there are aspects of his work that have been helpful in my thinking. Necropolitics, as it is formulated by Troyer, reinvents the term with particular care to the technology and social construction of the corpse. This term builds upon Troyer’s formulation of the ‘postmortem subject’—a socio-historical actor that is the result of a confluence of scientific and cultural developments during the mid-nineteenth century, which specifically transform the corpse into a kind of technologized and commodifiable thing.11 Necropolitics, out of this way of thinking, is an extension of the capitalized technology of embalming and its connection to the funerary industry that affords an engagement with politics of the corpse in a broader sense.

Revising and building upon this conceptual ground, Troyer leverages a distinction made from the greek root nekros to emphasize that necropolitics is a politics of the already dead, describing the technological-cultural apparatuses of care, maintenance and control over the human corpse. Building from Georgio Agemben’s engagement with the concentration camp,12 the control over the corpse becomes political in the ways it hides the production of death. Necropolitics in this context is a means to covertly explain away those death making processes: “when the authorities overseeing a camp decide that a dead body is not a living body made dead by the authorities in change, rather a dead body produced by an always-possible ‘natural death,’ then no wrongful act ever occurred.”13

My interest in both of these necropolitics is in how they engage with the dead at different levels and moments, and that they see death and the corpse as being produced by specific cultural actors for specific ideological reasons. Harriet Washington has noted that research hospitals are usually located within heavily black inner-city neighborhoods, harvesting research subjects from these communities at larger rates, doing research on these patients, affording a higher rate of exposure to potentially harmful research.14 Megan Rosenbloom succinctly describes the relationship that is formed by this research subject acquisition:

The rich invest in hospitals; the poor get treated; the knowledge gained by the doctors through observation of the poor can be used to better treat the rich. The clinical gaze extended to the way the collective body of the sick was viewed as a commodity.15

These necropolitical frameworks help stress why the specimen was created, how it is useful, and how its very being is usually tied to extractive processes which disproportionately affect poor, racialized, and otherwise othered communities in the United States. Tuberculosis researchers would not have specimens overfilling their museums (0.1.1) if there was not a large enough population that had been shunted into derelict, poorly ventilated housing, and if those same subjects were not chastised for their hygiene as a kind of moral failing (1.3.1; 1.3.3; 1.3.4).

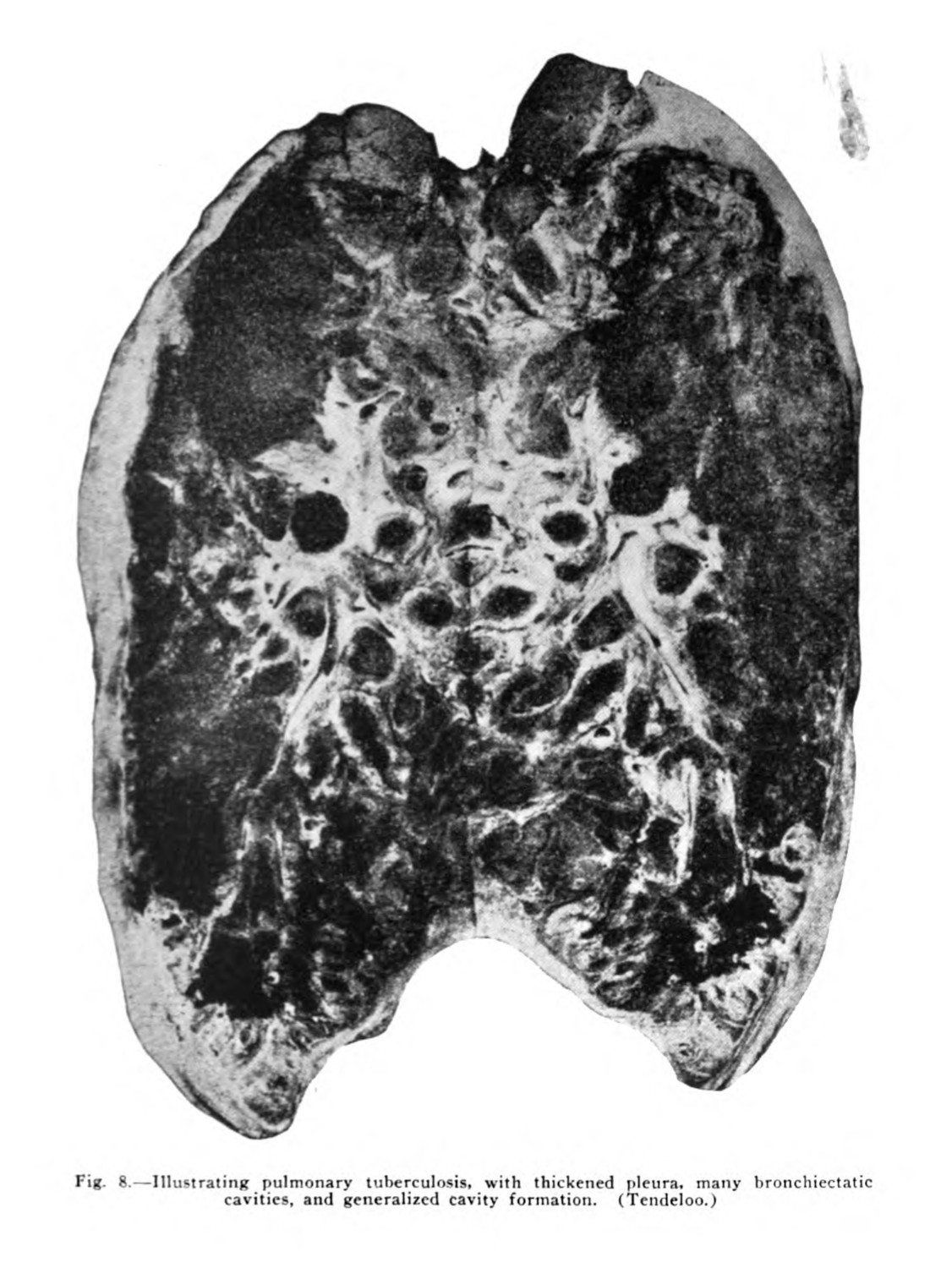

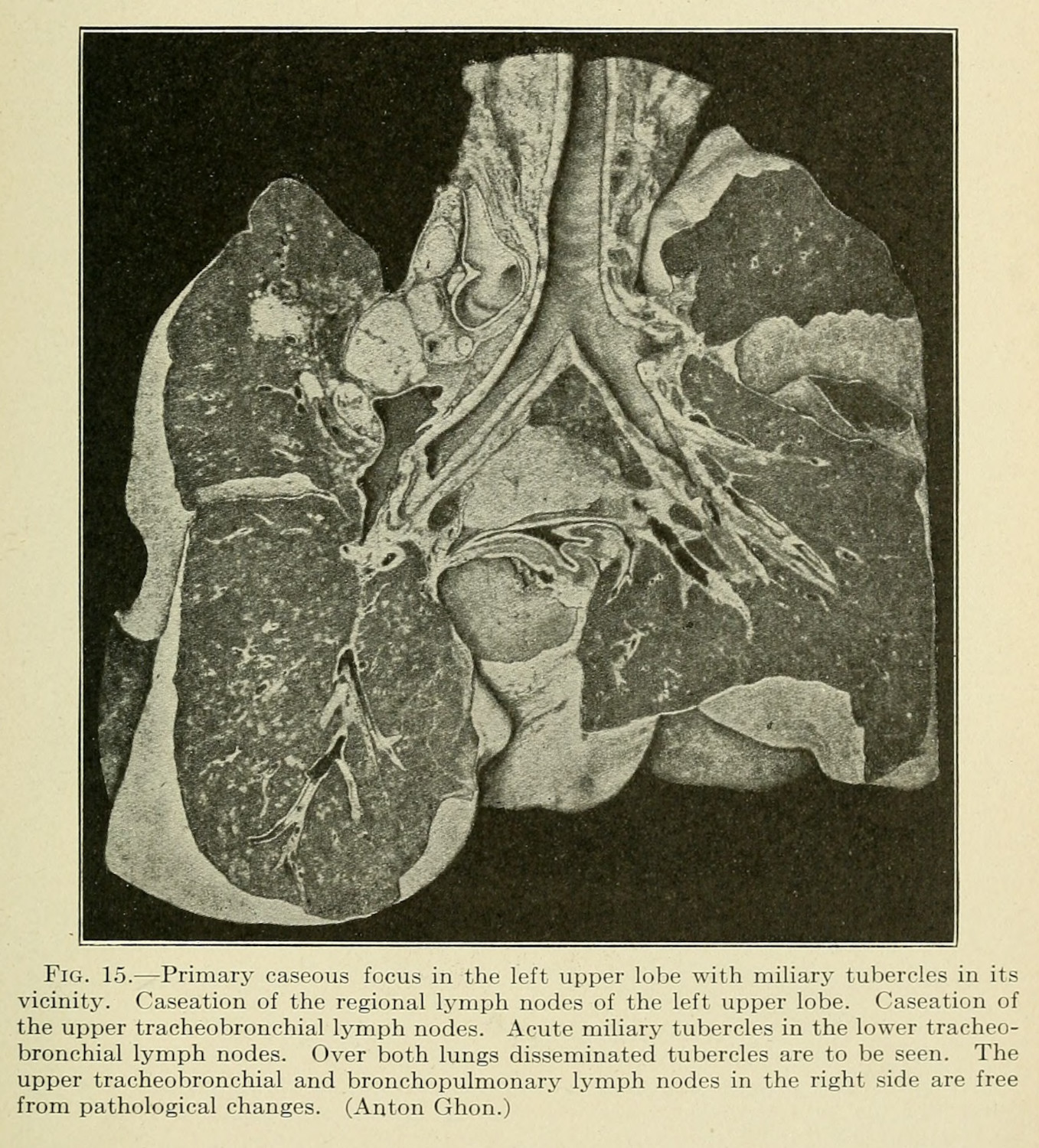

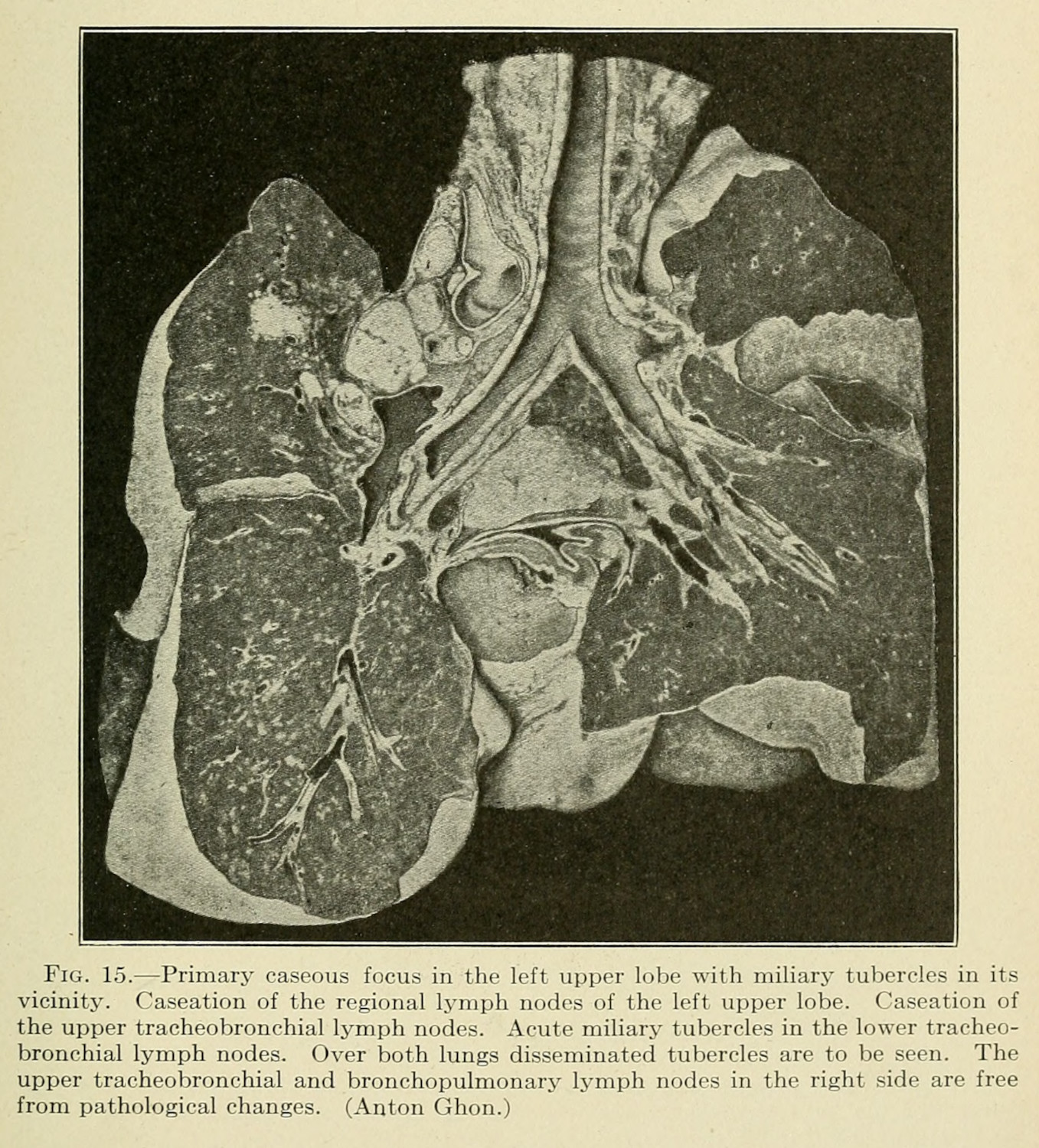

In order for a doctor to remove a tuberculous lung from a dead patient—in order to extract, cut it, submerge it in alcohol, and make it visible for scientific argument (fig. 1 & 2) (2.3.1)—the patient had to first die, and the production of that death is interlinked with structural imbalances which produce death for unwanted actors in a given culture. Most simply, the way a subject dies is deeply political, and often the production of that death is formulated in a Mbembian necropolitical calculation by actors in a given political moment. The production of a specimen from their corpse is the result of a Troyerian necropolitical relationship, insomuch as the technologies which produce and maintain the corpse are leveraged in a certain way to reveal and hide certain elements of the subject—revealing their malady and hiding their identity (2.3.1; 2.3.2).

Medical science depends on the body of the patient and sees the body as a resource. The patient’s body is valuable because of how it experienced illness, and because of this the continuity between life and death is epistemically central to its use in medical argument (2.2.3). The ways death was produced, either by bacterium, systemic neglect, or a confluence of attenuating factors, is of importance to understanding a given specimen. In this context, the images that I attend to have longer histories than the moment of their visual capture. There is always some living subject from which it was drawn, and the production of that specimen is not entirely determined by the will of a medical researcher, but also an entwined network of social, cultural, historical, and biological actors.16 The specimens have a life history that precedes their rhetorical utility in scientific research (2.2.1).17

-

I have written about death cultures in other contexts.

Purcell, Sean. “Dermographic Opacities.” Epoiesen, 2022. http://dx.doi.org/10.22215/epoiesen/2022.1. ↩

-

Some of these conversations tend to take an idyllic approach to premodern life and death practices.

Ariés, Philippe. Western Attitude toward Death: From the Middle Ages to the Present. Translated by Patricia M. Ranum. Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1975; Kübler-Ross, Elisabeth. On Death & Dying: What the Dying Have to Teach Doctors, Nurses, Clergy & Their Own Families. New York: Scribner, 1969; Saunders, Cicely, and Mary Baines. Living with Dying: The Management of Terminal Disease. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1983. ↩

-

Loftland, Lyn. The Craft of Dying: The Modern Face of Death. 40th Anniversary Edition. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2019. ↩

-

Ariés, Philippe. Western Attitude toward Death: From the Middle Ages to the Present. Translated by Patricia M. Ranum. Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1975. ↩

-

The ‘good death’ and ‘happy death’ movements have an impact in this discussion. In the past decade death studies has had a popular following, largely thanks to the work of mortician Caitlin Doughty, and her popular Youtube series Ask a Mortician. https://www.youtube.com/@AskAMortician ↩

-

Casid, Jill H. “Doing Things with Being Undone.” Journal of Visual Culture 18, no. 1 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1177/1470412919825817. ↩

-

Latour, Bruno. “Agency at the Time of the Anthropocene.” New Literary History 45, no. 1 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1353/nlh.2014.0003; Chakrabarty, Dipesh. “Humanities in the Anthropocene: The Crisis of an Enduring Kantian Fable.” New Literary History 47, no. 2–3 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1353/nlh.2016.0019. ↩

-

Purcell, Sean. “Rendering in Analog Games: Dissected Puzzles and Georgian Death Culture.” Game Studies 23, no. 1 (2023). ↩

-

Troyer, John. Technologies of the Human Corpse. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2020. 190. ↩

-

Mbembe, Achille. “Necropolitics.” Translated by Libby Meintjes. Public Culture 15, no. 1 (2003): 11–40. Mbembe, Achille. Necropolitics. Translated by Steven Corcoran. Duke University Press, 2019. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1131298. ↩

-

Troyer, John. “Embalmed Vision.” Mortality 12, no. 1 (2007): 22–47. ↩

-

Agamben, Giorgio. Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life. Translated by Daniel Heller-Roazen. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1998. ↩

-

Troyer, John. Technologies of the Human Corpse. 130. ↩

-

Washington, Harriet A. Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present. New York: Harlem Moon & Broadway Books, 2006. 6-7. ↩

-

Rosenbloom, Megan. Dark Archives: A Librarian’s Investigation into the Science and History of Books Bound in Human Skin. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2020. 46. ↩

-

Fitzgerald, Des, and Felicity Callard. “Entangling the Medical Humanities.” In The Edinbgurgh Companion to the Critical Medical Humanities, edited by Anne Whitehead and Angela Woods, 35–49. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2016. ↩

-

Kopytoff, Igor. “The Cultural Biography of Things: Commoditization as Process.” In The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspectives, edited by Arjun Appadurai, 64–91. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986. ↩