Introduction

Specimen Studies

0.1.1 | 0.1.2 | 0.1.3 | 0.1.4 | 0.1.5Methods

0.2.1 | 0.2.2The Structure of this Dissertation

0.3.1Tuberculosis' Visual Culture

Visual Practices in Medical Culture

1.1.1 | 1.1.2 | 1.1.3Seeing and Settling in the Sanatorium Movement

1.2.1 | 1.2.2 | 1.2.3 | 1.2.4 | 1.2.5Teaching Public Health

1.3.1 | 1.3.2 | 1.3.3 | 1.3.4 | 1.3.5Representing Doctors in Tuberculous Contexts

1.4.1 | 1.4.2Using Human Specimens in the Study of Tuberculosis

Seeing Disease in Methyl Violet

2.1.1 | 2.1.2 | 2.1.3 | 2.1.4Case Histories

2.2.1 | 2.2.2 | 2.2.3 | 2.2.4Visceral Processes

2.3.1 | 2.3.2Relation

2.4.1 | 2.4.2 | 2.4.3Arts-Based Inquiry

Introduction

3.1.1 | 3.1.2 | 3.1.3 | 3.1.4Terminal Imaginaries & Tuberculous Imaginaries

3.2.1 | 3.2.2 | 3.2.3 | 3.2.4 | 3.2.5 | 3.2.6Dermographic Opacities

3.3.1 | 3.3.2 | 3.3.3 | 3.3.4Tactical Pretensions

3.4.1 | 3.4.2 | 3.4.3Designing Opacity

A Shift towards the Anticolonial

4.1.1 | 4.1.2 | 4.1.3 | 4.1.4Refusals and Opacities

4.2.1 | 4.2.2 | 4.2.3 | 4.2.4Digital and Ethical Workflows

4.3.1 | 4.3.2 | 4.3.3 | 4.3.4 | 4.3.5Conclusion

4.4.1Coda

Prometheus Undone

5.1.1 | 5.1.2 | 5.1.3 | 5.1.4Appendix

The Tuberculosis Corpus

X.1.1 | X.1.2 | X.1.3Web Design

X.2.1 | X.2.2 | X.2.3 | X.2.4Installation Materials

X.3.1 | X.3.2 | X.3.3Index

Pathology depends on two conceptual frameworks. The first, described by Michel Foucault in The Birth of the Clinic, is the clinical gaze—which contrasts the patient’s body against an idealized imagination of human anatomy to see difference as disease, and disease as difference (1.1.2; 2.2.2).1 The second is that in order to understand the cause of the pathological phenomenon, there needs to documentation surrounding the body from which the specimen examined in a pathological study was extracted. There is a need for a history (2.2.3).

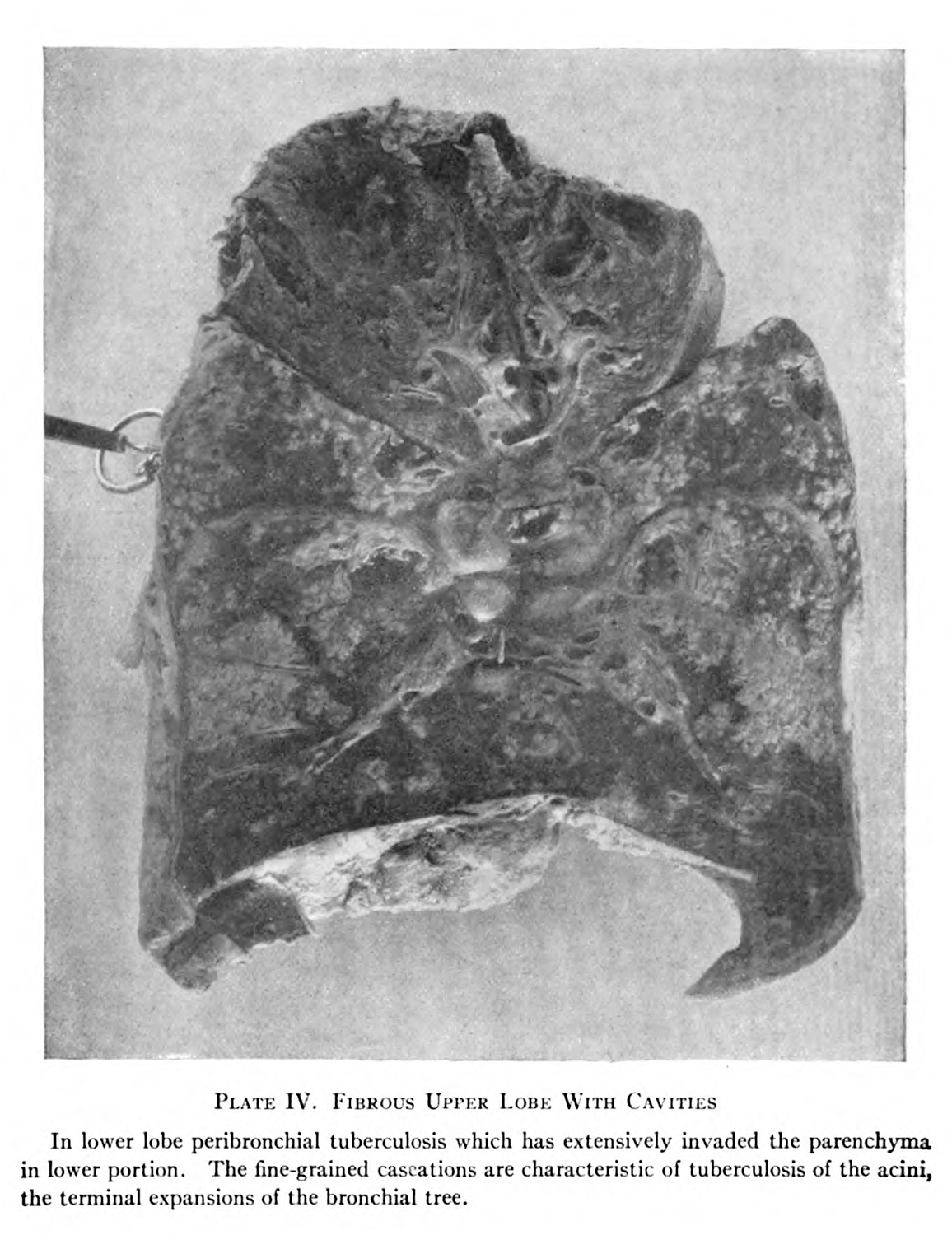

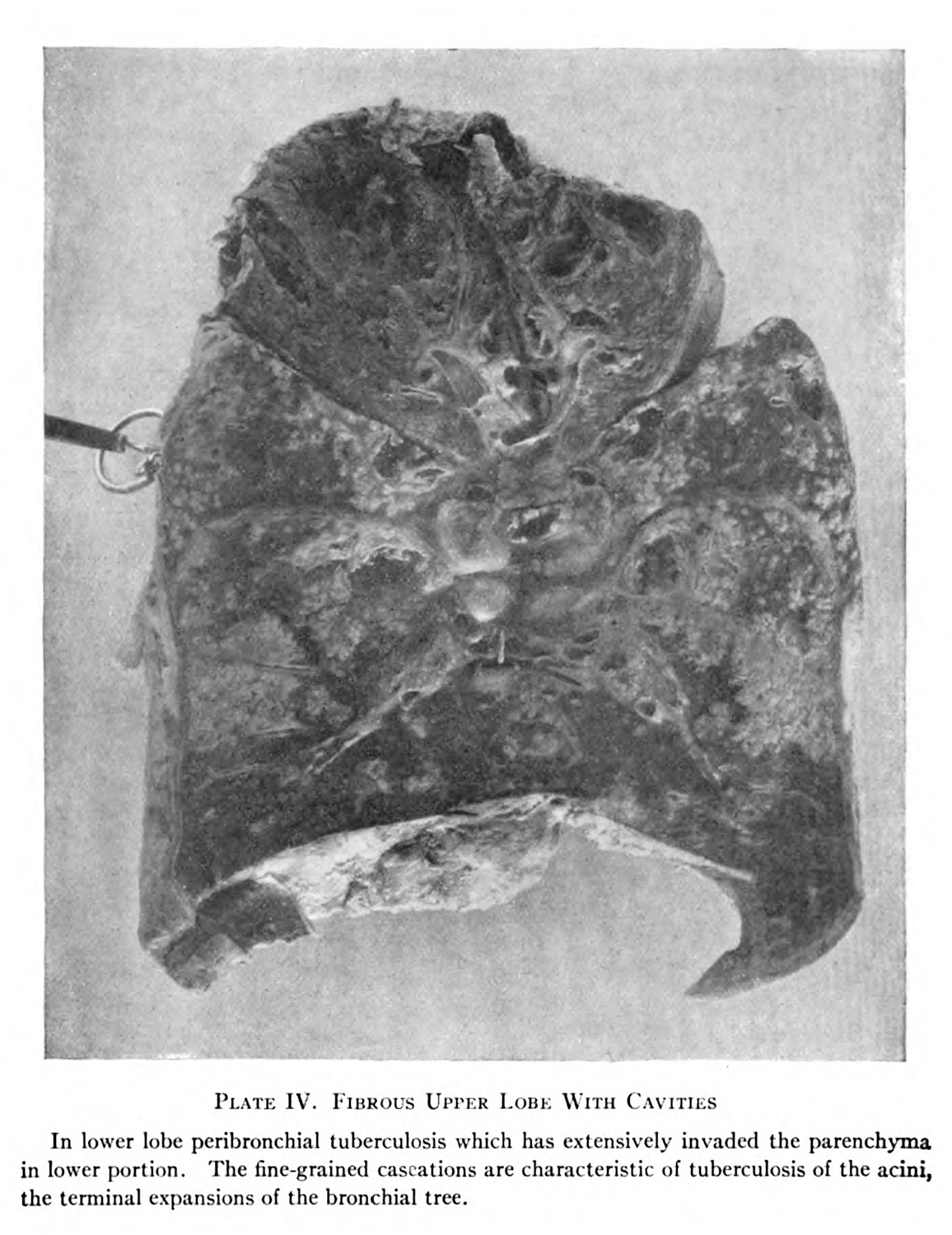

Throughout this dissertation, I have articulated the specimen as something that is constructed, something that is framed, something that is used to articulate an argument. What I want to stress is that this process of faming operates on systems of epistemic and ideological privilege: what is deemed important is what is allowed to remain, what is framed, what is described. To create a lung specimen like the one described in the previous section (2.3.1) (fig. 1), there is an excision of superfluous material: it is brought out of the body, taken out of its natural context, and the human viscera that would obscure vision is carefully taken away. The patient’s history is treated in the same manner: only the important parts matter and everything else can be allowed to slough down the drain (2.2.3).

The reduction of the subject is a necessary function, partly because it focuses the creation of the research object. A whole preserved cadaver would be a poor tool to describe a unique kidney pathology. Reduction distills concrete elements, and with that, something which can be known in isolation. Botanist and Indigenous scholar Robin Wall Kimmerer summarizes this reduction, writing,

I did learn another language in science, though, one of careful observation, an intimate vocabulary that names each little part. To name and describe you first must see, and science polishes the gift of seeing. I honor the strength of the language that has become a second tongue to me. But beneath the richness of its vocabulary and its descriptive power, something is missing, the same something that swells around you and in you when you listen to the world. Science can be a language of distance which reduces a being to its working parts; it is a language of objects. The language scientists speak, however precise, is based on a profound error in grammar, an omission, a grave loss in translation from the native language of these shores.2

For Kimmerer, who uses sciences as a contrast to the language of her people, the Potawatomi, to describe how central animism is for communicating in their culture. The separation of objects from one another in scientific language distills and disciplines them in such a manner that makes them causally distinct for specific arguments. The scale of separation, from body to organ to cell to chemical reaction, happens differently in different discourses, but the implicit idea that they can be reduced or that they can be isolated is part and parcel of scientific argument.

What is important for pathology is that the reduction from singular object with a history to a representative object—that which represents a tuberculous lung—brings with it a generalizability. It is not a patient’s lung, it is tuberculosis of the lung as it presents in a certain context. The distillation simplifies into a single representation that is decidedly unique: it is collectable, valuable, and useful (0.1.4).

This process of creation emphasizes the description and representation of a naturally occurring phenomena. While some arms of medical knowledge, like physiology, focuses on experimental science, where phenomena are reduced and reproduced, pathology at the turn of the twentieth century is more descriptive: it collects samples and finds its arguments in the aggregate.

-

Foucault, Michel. The Birth of the Clinic: An Archeology of Medical Perception. Translated by A. M. Sheridan Smith. New York: Vintage Books, 1994. ↩

-

Kimmerer, Robin Wall. Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants. Minneapolis: Milkweed Editions, 2013. 48-49. ↩