Introduction

Specimen Studies

0.1.1 | 0.1.2 | 0.1.3 | 0.1.4 | 0.1.5Methods

0.2.1 | 0.2.2The Structure of this Dissertation

0.3.1Tuberculosis' Visual Culture

Visual Practices in Medical Culture

1.1.1 | 1.1.2 | 1.1.3Seeing and Settling in the Sanatorium Movement

1.2.1 | 1.2.2 | 1.2.3 | 1.2.4 | 1.2.5Teaching Public Health

1.3.1 | 1.3.2 | 1.3.3 | 1.3.4 | 1.3.5Representing Doctors in Tuberculous Contexts

1.4.1 | 1.4.2Using Human Specimens in the Study of Tuberculosis

Seeing Disease in Methyl Violet

2.1.1 | 2.1.2 | 2.1.3 | 2.1.4Case Histories

2.2.1 | 2.2.2 | 2.2.3 | 2.2.4Visceral Processes

2.3.1 | 2.3.2Relation

2.4.1 | 2.4.2 | 2.4.3Arts-Based Inquiry

Introduction

3.1.1 | 3.1.2 | 3.1.3 | 3.1.4Terminal Imaginaries & Tuberculous Imaginaries

3.2.1 | 3.2.2 | 3.2.3 | 3.2.4 | 3.2.5 | 3.2.6Dermographic Opacities

3.3.1 | 3.3.2 | 3.3.3 | 3.3.4Tactical Pretensions

3.4.1 | 3.4.2 | 3.4.3Designing Opacity

A Shift towards the Anticolonial

4.1.1 | 4.1.2 | 4.1.3 | 4.1.4Refusals and Opacities

4.2.1 | 4.2.2 | 4.2.3 | 4.2.4Digital and Ethical Workflows

4.3.1 | 4.3.2 | 4.3.3 | 4.3.4 | 4.3.5Conclusion

4.4.1Coda

Prometheus Undone

5.1.1 | 5.1.2 | 5.1.3 | 5.1.4Appendix

The Tuberculosis Corpus

X.1.1 | X.1.2 | X.1.3Web Design

X.2.1 | X.2.2 | X.2.3 | X.2.4Installation Materials

X.3.1 | X.3.2 | X.3.3Index

There is a logical fallacy which pathology perpetuates: that the unique phenomena embodied in a patient which is used in a case study can be isolated and generalized. The processes of isolation, extraction, and distillation are dependent on a subject’s broader embedded historical and cultural context.

In making my argument for this chapter, I have rallied discourses around a number of fields from new materialism (2.1.4) to death studies (2.2.4) to Indigenous critiques of science (2.3.2). Doing this I find myself needing to link my own project to this same conceptual fallacy: I too have distilled, isolated, and simplified these research objects with deep, entangled histories.

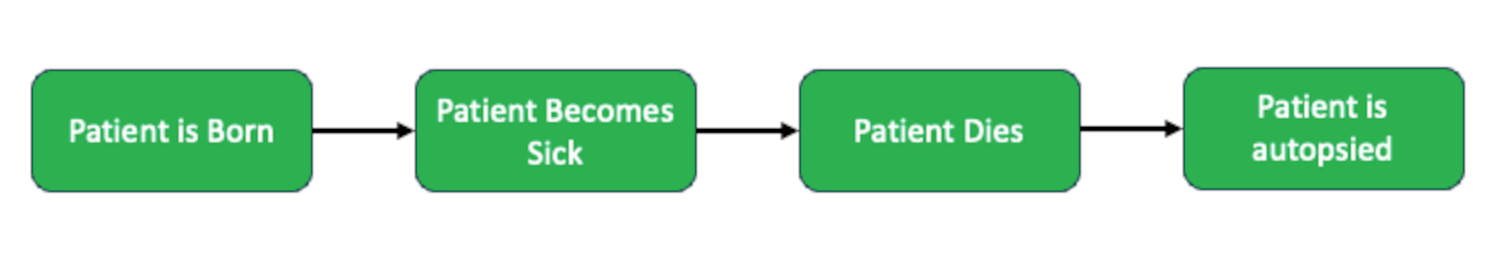

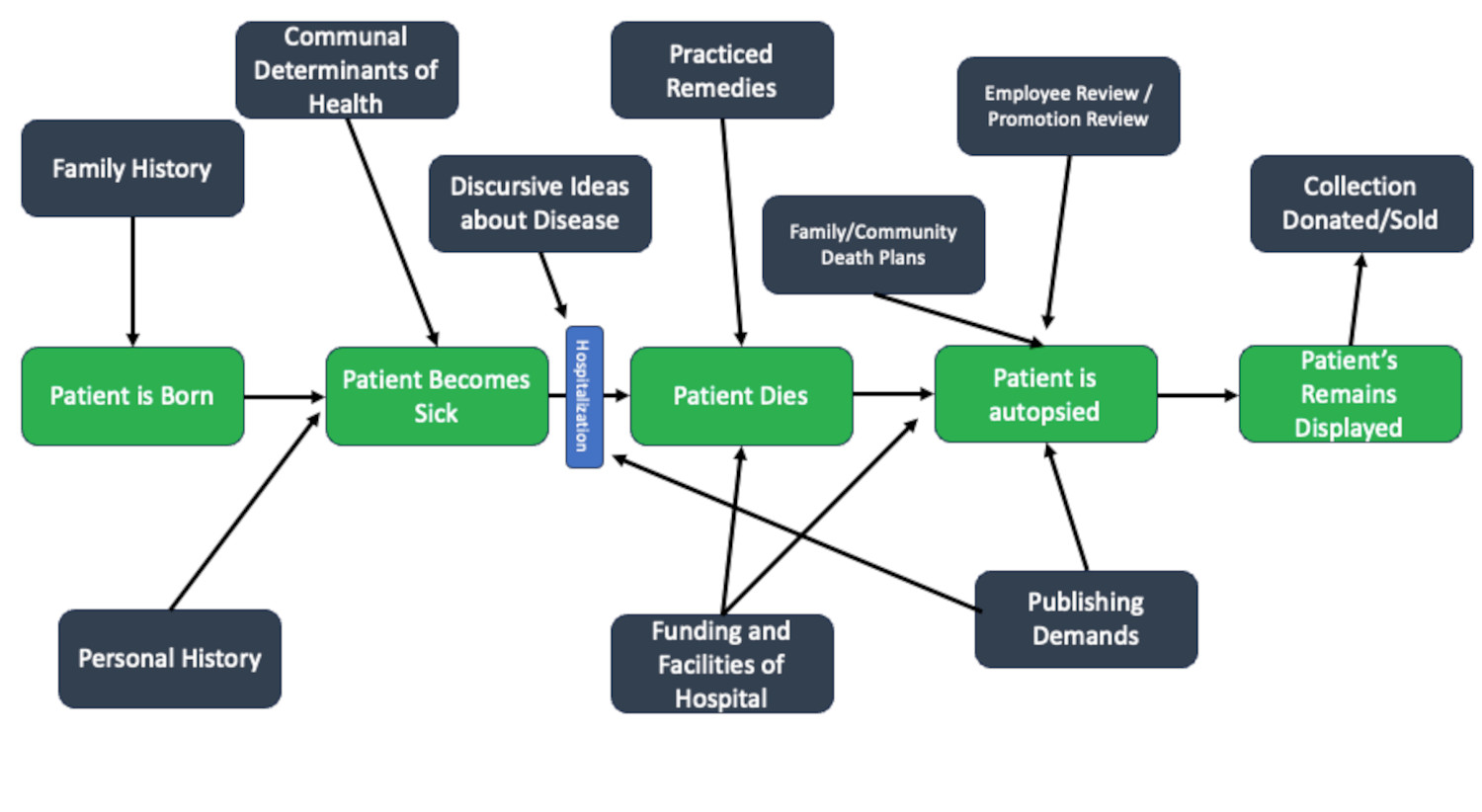

Much of my argument depends on a new materialist presumption that the technologies which surround representational practices have their own non-human agencies, histories, and interdependencies (2.1.4). The human subject is not severable from the specimen because its various embodied, material exigencies are the very stuff from which scientists make their claims. To use a simple diagram, I have argued a causal link between disease progression as a patient history (2.2.2), the extraction of an organ at autopsy (2.3.1) and the epistemic foundations of pathological argumentation (2.3.2). I can represent it as a sequential process: a timeline (table 1).

I could conceive this as a life history of a specimen, which attends to the various moments, cultural valencies, and material transformations which contextualize a research object in a given culture.1 New materialists have articulated a limitation with a life history model, insomuch as these objects do not just arbitrarily appear in culture, nor do they disappear (2.2.1).2 To produce any material culture artifact requires a detailed linkage of processes which are each also dependent on even more complex interrelations. In new materialism the turn away from human-centric models was met, in part, by an evacuation of anthropocentrism in humanistic knowledge production: there are entire universes which humans may touch but do not deterministically control.3

The ecologically minded, posthumanist shift of thinkers like Bruno Latour, Graham Harmon, Jane Bennet, and Karen Barad have helped me move away from thinking about representation as being something for humans and between humans.4 They have pushed me to think of all of the nuances, traces, and contacts between multiple non-human actors, as well as between humans and the non-human world. At the same time, the limitations of these approaches are obvious for the current project, as this dissertation is interested in the impact of human practices on human lives and human bodies. But there is a second larger problem: new materialism tends to circumvent the human, cultural problems which undergird and oppress many actors within human cultures. Lane Nooney summarizes this problem:

[w]hile many of the most provocative and innovative materialist media theories attempt to productively short circuit the subject-object division by displaying how media are active agents in the world, these efforts often wind up simply rearranging actor-network deck chairs, envisioning histories and theories without corporeal or discursive bodies.5

New materialist ideas are provocative, but they seem best at opening new terrains for future research, affording new extractive possibilities for humanists, while often ignoring the very human needs of othered subjects within our cultures (5.1.2; 5.1.3).

Importantly, for this dissertation and for this chapter, frameworks like object-oriented ontology (OOO) and actor network theory (ANT) share an ethical problem: they evacuate the human and in doing so evacuate the responsibility researchers have to their research interlocutors, research subjects, and research objects. They create a new isolated environment to perform new forms of research (2.4.2).

Returning to the timeline above, I can break it down hierarchically and temporally to think about the complexity between humans and nonhumans in that basic timeline (table 2). A pathological specimen depends on both the human subject and their history as well as on the agency of Mycobacterium tuberculosis; it depends on the technologies of scalpels, and glassmaking, and spirit production (2.1.3); it depends on aesthetic categories defined within the biomedical discourse (2.1.3); it depends on processes of preservation and distribution. Attending to parts of this larger network of biomedical representation enabled me to make the claims that I do, but there is a bigger problem: in making this argument I do nothing to address the ethical center of this dissertation. I can talk about the creation of specimens. I can argue that they have a causal link with a human subject who was probably denied consent to use their bodies in this way, but I also become complicit in this process.

-

Kopytoff, Igor. “The Cultural Biography of Things: Commoditization as Process.” In The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspectives, edited by Arjun Appadurai, 64–91. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986. ↩

-

Guins, Raiford. Game After: A Cultural Study of Video Game Afterlife. The MIT Press, 2014. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt9qf8c8; Purcell, Sean. “Rendering in Analog Games: Dissected Puzzles and Georgian Death Culture.” Game Studies 23, no. 1 (2023). ↩

-

Barad, Karen. Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Durham & London: Duke University Press, 2007; Bennett, Jane. “Systems and Things: A Response to Graham Harman and Timothy Morton.” Source: New Literary History 43, no. 2 (2012): 225–33; Harman, Graham. “Object-Oriented Ontology.” In Palgrave Handbook of Posthumanism in Film and Television, edited by MIcchael Hauskeller, Michael Carbonell, and Thomas D. Philbeck. London & New York: Palgrave MacMillan Limited, 2016. ↩

-

Harman, Graham. “Object-Oriented Ontology.” In Palgrave Handbook of Posthumanism in Film and Television, edited by MIcchael Hauskeller, Michael Carbonell, and Thomas D. Philbeck. London & New York: Palgrave MacMillan Limited, 2016; Bennett, Jane. “Systems and Things: A Response to Graham Harmon and Timothy Morton.” Source: New Literary History 43, no. 2 (2012): 225–33; Barad, Karen. Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Durham & London: Duke University Press, 2007. ↩

-

Nooney, Laine. “A Pedestal, A Table, A Love Letter: Archaeologies of Gender in Videogame History.” Game Studies 13, no. 2 (2013). ↩