Introduction

Specimen Studies

0.1.1 | 0.1.2 | 0.1.3 | 0.1.4 | 0.1.5Methods

0.2.1 | 0.2.2The Structure of this Dissertation

0.3.1Tuberculosis' Visual Culture

Visual Practices in Medical Culture

1.1.1 | 1.1.2 | 1.1.3Seeing and Settling in the Sanatorium Movement

1.2.1 | 1.2.2 | 1.2.3 | 1.2.4 | 1.2.5Teaching Public Health

1.3.1 | 1.3.2 | 1.3.3 | 1.3.4 | 1.3.5Representing Doctors in Tuberculous Contexts

1.4.1 | 1.4.2Using Human Specimens in the Study of Tuberculosis

Seeing Disease in Methyl Violet

2.1.1 | 2.1.2 | 2.1.3 | 2.1.4Case Histories

2.2.1 | 2.2.2 | 2.2.3 | 2.2.4Visceral Processes

2.3.1 | 2.3.2Relation

2.4.1 | 2.4.2 | 2.4.3Arts-Based Inquiry

Introduction

3.1.1 | 3.1.2 | 3.1.3 | 3.1.4Terminal Imaginaries & Tuberculous Imaginaries

3.2.1 | 3.2.2 | 3.2.3 | 3.2.4 | 3.2.5 | 3.2.6Dermographic Opacities

3.3.1 | 3.3.2 | 3.3.3 | 3.3.4Tactical Pretensions

3.4.1 | 3.4.2 | 3.4.3Designing Opacity

A Shift towards the Anticolonial

4.1.1 | 4.1.2 | 4.1.3 | 4.1.4Refusals and Opacities

4.2.1 | 4.2.2 | 4.2.3 | 4.2.4Digital and Ethical Workflows

4.3.1 | 4.3.2 | 4.3.3 | 4.3.4 | 4.3.5Conclusion

4.4.1Coda

Prometheus Undone

5.1.1 | 5.1.2 | 5.1.3 | 5.1.4Appendix

The Tuberculosis Corpus

X.1.1 | X.1.2 | X.1.3Web Design

X.2.1 | X.2.2 | X.2.3 | X.2.4Installation Materials

X.3.1 | X.3.2 | X.3.3Index

I want to point to Actor Network Theory (ANT) as an example to make more clear my ethical concerns with posthuman ontologies. ANT is characterized by the non-hierarchical structure of a network, built by relationships between nodes but not superiority of any node in the system. The structure and relation of its argument is devised precisely to do away with spatial metaphor and the hierarchies that develop in the process. If I were to describe Robert Koch or Louis Pasteur without ANT, I may say that Koch is the better scientist, or that Pasteur’s work has more direct cultural impacts, and by doing so, I imply, intentionally or otherwise, that one is superior to the other. The notion of ‘first’ or ‘better’ has cultural and discursive significance that makes the claim into a value judgement. ANT challenges scholars to think about how we might make arguments if Koch and Pasteur are related, but not better or worse than one another. It gives space for actors who may not have political, cultural, or social capital to enter the conversation. Latour’s emphasis on the absence of hierarchy gives him a powerful rhetorical position to stand on, especially in relation to the science wars which he and his colleagues weathered, and because his philosophical ideas rally against the hierarchies implicit in the dominant philosophical discourse.

While very productive, Latour’s work is filled with these ‘smarter than thou’ rhetorical gestures, which are devised as gambits to prove his constructivist viewpoints in an antagonistic scholarly domain. He, and colleague Steve Woolgar, claim at the end of Laboratory Life that their work is “‘entirely unconvincing’” to stress that their arguments have no authority above the scientific epistemics they worked to undermine (3.4.1).1 ANT’s logic is built on an infinitely nested fractalism: everything is a network, which is interconnected by every actor within it, and meaning, itself a part of the network, is derived from its interlinkages between actors. Latour writes,

Actor-networks do connect, and by connecting with one another provide an explanation of themselves, the only one there is for ANT. What is an explanation? The attachment of a set of practices that control or interfere in one another. No explanation is stronger or more powerful than providing connections among unrelated elements or showing how one element holds many others.2

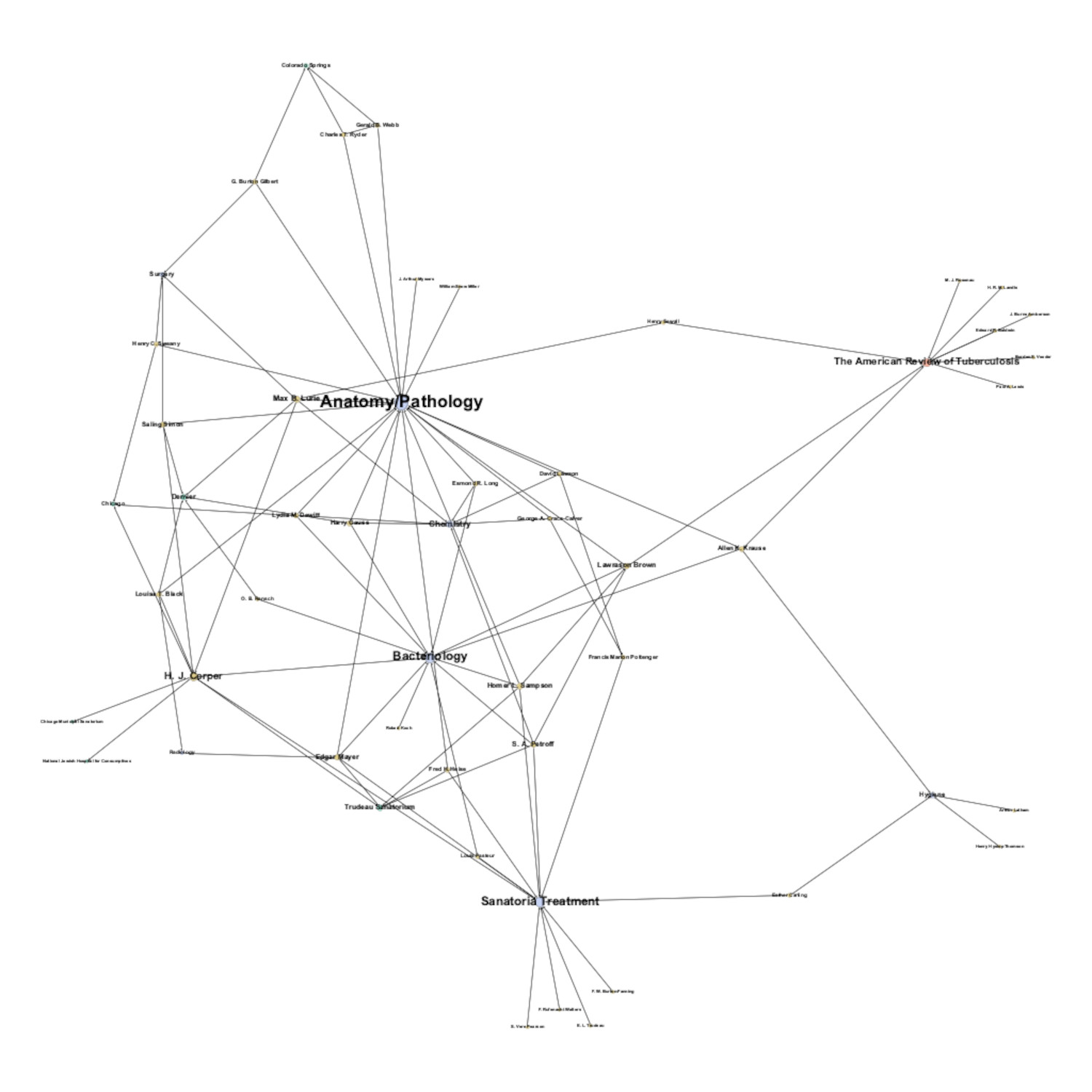

The connections that build ANT can be mapped to any subject. Take, for example, a simple network graph based on some important actors in tuberculosis corpus (X.1.1) (table 1). The nodes—the nouns in a network, represented by circles—include prominent researchers associated with the American Review of Tuberculosis, a few sanatoria, the places those institutions and doctors worked, and the broad scholarly discourses in which they wrote. The edges—the lines that connect nodes—are formed from the relationship these nodes share: H. J. Corper is related to bacteriology; Louisa T. Black is related to radiology. The connections in actor network theory are always constructed by the researcher, so they always carry some amount of arbitrariness. What a network reveals, through its emphasis on connection, is that some actors that may seem significant—like H. J. Corper, who has dozens of publications—do not have prominence in the graph. Corper is connected, but no more connected than Lawrason Brown or Allen K. Krauss or Louisa T. Black.

The fractalism of Latour’s theory provides a canny defense from critique. ANT devours everything into a complex tangle of interrelations, which researchers navigate to construct their arguments. One cannot critique ANT because a critique assumes a hierarchical, semiotic turn where the theory contains an explicit cultural meaning. Latour can just argue that, in a network, ANT is connected to all of these other objects, ideas, materials, concepts, people, publications, whose relation and interlinkage makes the theory operate. Latour’s work is intentionally slippery, which conveys an idealized pure theoretical framework which is often, obviously impossible.

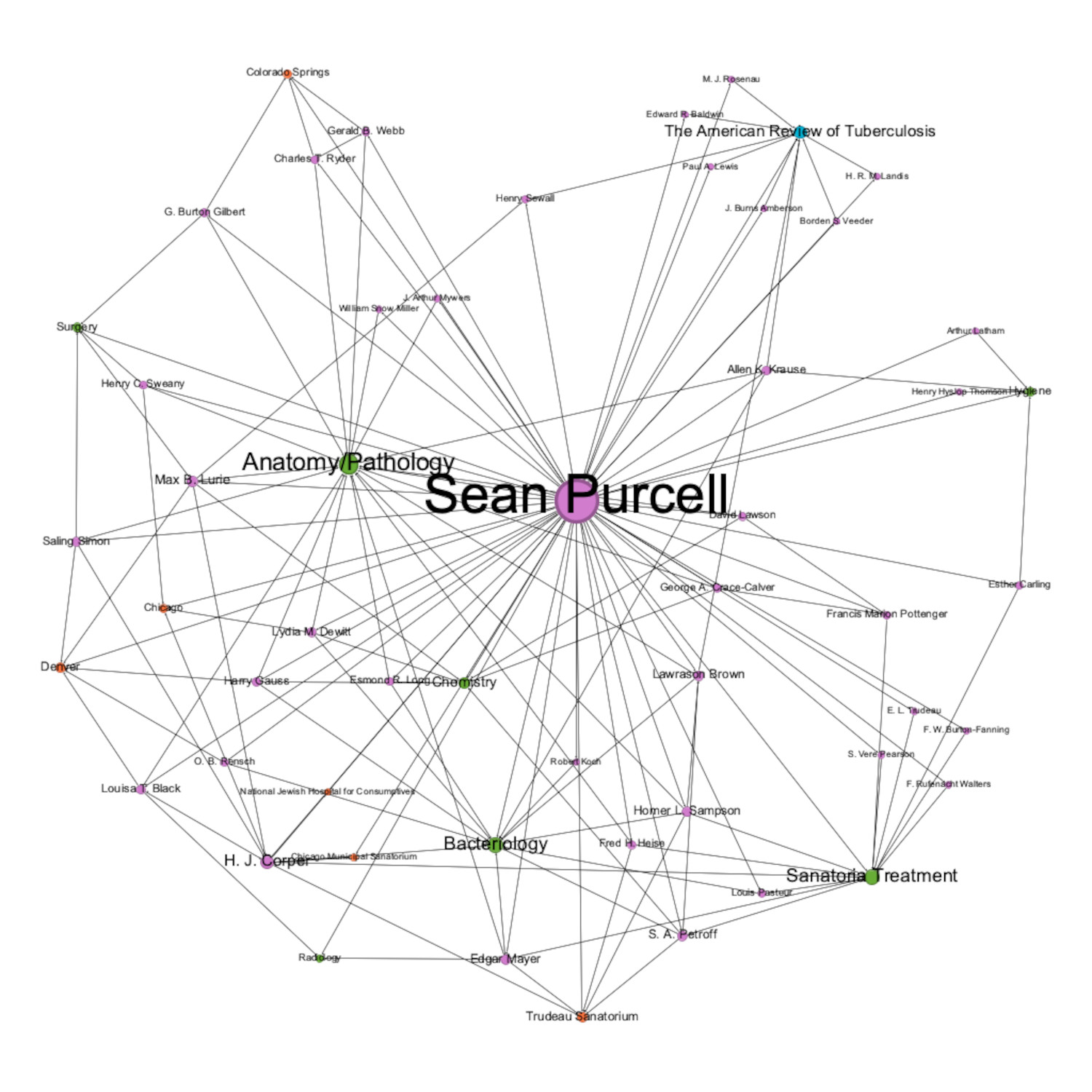

The problem with ANT and other material-minded theories is two-fold: 1) it is well and good to theorize radical approaches to philosophical problems, but they do no good if they do not give people and communities the tools to improve their lives,3 and 2) ANT provides a helpful framework to think about relationality, but every node is bound by an implicit relationship that is points back to the researcher. While Latour implies this, stressing the theory’s semantic constructiveness, and thus the subjectivity of any network, a network cannot function as an analytical tool if every point connects back to the researcher in question (table 2). The researcher’s absence maintains a central hierarchy in western thought: one in which the researcher maintains power over their research object. ANT challenges the centrality of the human, but maintains the value of the researcher themselves.

My hope here is not to throw the baby out with the bathwater, but to point to how the theoretical underpinnings of new materialist thinking tend to get too precious about their rhetorical standing to the detriment of their potential political and social interventions. What is missing in these frameworks is an ethics of responsibility, reciprocity and relationality.

I use the term relationality to refer to an array of interrelated epistemic, ontological, methodological and axiological frameworks shared by Indigenous peoples and researchers.4 As I argued in the introduction, relationality in research refers to the ways academics build relationships with their interlocutors (0.1.5). Interlocutor, here, is very abstract, because it could mean people—like Koch or a patient—as well a place, a history, a research object, or a concept.5

This relationship makes a researcher obligated to their interlocutors: to take care of, to support, to be empathetic toward, to engage with on a level of equality.6 Obligation means trying to piece out the various interrelated material, cultural, ideological, historical, conceptual, and epistemic connections that bind those interlocutors to one another, as well as to the researcher themselves, and in understanding these connections caring for all of those made into relation with one another.7

As I mentioned above, the problem that I have is that the researcher is evacuated in much of western thought, and that there is an ideology that supposes their research is necessary, meaningful, and productive for the functioning of society. In the case of medical science, every essay published after Koch’s microbial discoveries can be seen as necessary for the articulation of knowledge about tuberculosis; however, as those essays have essentially been lost to time, and their utility being only valuable for medical historians, their value is at best suspect. Moreover, considering that the bulk of essays published in peer review journals in the twenty-first century, both in the sciences and the humanities, will not be read by anyone except for the journal editors, I am skeptical as to the supreme, unquestionable authority of this knowledge assumption.

One of my goals throughout this dissertation is to deflate the value of knowledge in bulk, calling for instead careful, conscious, ethical approaches to research (3.4.2; 5.1.3). To do this requires the dissolution of the hierarchy of knowledge as articulated in academic institutions, because so much of that hierarchy is built out of exclusion of subaltern ideas, perspectives, and epistemologies.8 Moreover, this supposed superiority is articulated in ways that make researchers have power over their research subjects and objects (0.1.4).

-

Latour, Bruno, and Steve Woolgar. Laboratory Life: The Construction of Scientific Facts. 2nd ed. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1986. 284. ↩

-

Latour, Bruno. “On Actor-Network Theory: A Few Clarifications Plus More Than a Few Complications.” Soziale Welt 47 (1996): 375. ↩

-

Hale, Charles R. “Activist Research v. Cultural Critique: Indigenous Land Rights and the Contradictions of Politically Engaged Anthropology.” Cultural Anthropology 21, no. 1 (2006): 96–120. ↩

-

I use these four terms to speak to relate the way Shawn Wilson articulates Indigenous knowledge practices. As my own project revolves around questions of epistemology, methodology, and ethics, I will not be referencing the other valences which Indigenous viewpoints shift and structure knowledge.

Further, Édouard Glissant’s work also posits a kind of relationally, which rhymes with, but does not entirely correspond to indigenous frameworks. His scholarship is indebted to Afro-Carribean practices and cultures, which are distinct from Indigenous cultures.

Wilson, Shawn. Research Is Ceremony: Indigenous Research Methods. Halifax & Winnipeg: Fernwood Publishing, 2008.

Glissant, Édouard. Poetics of Relation. Translated by Betsy Wing. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1997. ↩

-

Wilson, Shawn. Research is Ceremony. ↩

-

TallBear, Kim. “Standing With and Speaking as Faith: A Feminist-Indigenous Approach to Inquiry.” Journal of Research Practice 10, no. 2 (2014). ↩

-

Liboiron, Max, Emily Simmonds, Edward Allen, Emily Wells, Jessica Melvin, Alex Zahara, Charles Mather, and All Our Teachers. “Doing Ethics with Cod.” In Making & Doing: Activating STS through Knowledge Expression and Travel, edited by Gary Lee Downey and Teun Zuiderent-Jerak, 137–53. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2021. ↩

-

Bhimull, Chandra, Gabrielle Hecht, Edward Jones-Imhotep, Chakenetsa Mavhunga, Lisa Nakamura, and Asif Saddiqi. “Systemic and Epistemic Racism in the History of Technology.” Technology and Culture 63, no. 4 (2022): 935–52. ↩