Introduction

Specimen Studies

0.1.1 | 0.1.2 | 0.1.3 | 0.1.4 | 0.1.5Methods

0.2.1 | 0.2.2The Structure of this Dissertation

0.3.1Tuberculosis' Visual Culture

Visual Practices in Medical Culture

1.1.1 | 1.1.2 | 1.1.3Seeing and Settling in the Sanatorium Movement

1.2.1 | 1.2.2 | 1.2.3 | 1.2.4 | 1.2.5Teaching Public Health

1.3.1 | 1.3.2 | 1.3.3 | 1.3.4 | 1.3.5Representing Doctors in Tuberculous Contexts

1.4.1 | 1.4.2Using Human Specimens in the Study of Tuberculosis

Seeing Disease in Methyl Violet

2.1.1 | 2.1.2 | 2.1.3 | 2.1.4Case Histories

2.2.1 | 2.2.2 | 2.2.3 | 2.2.4Visceral Processes

2.3.1 | 2.3.2Relation

2.4.1 | 2.4.2 | 2.4.3Arts-Based Inquiry

Introduction

3.1.1 | 3.1.2 | 3.1.3 | 3.1.4Terminal Imaginaries & Tuberculous Imaginaries

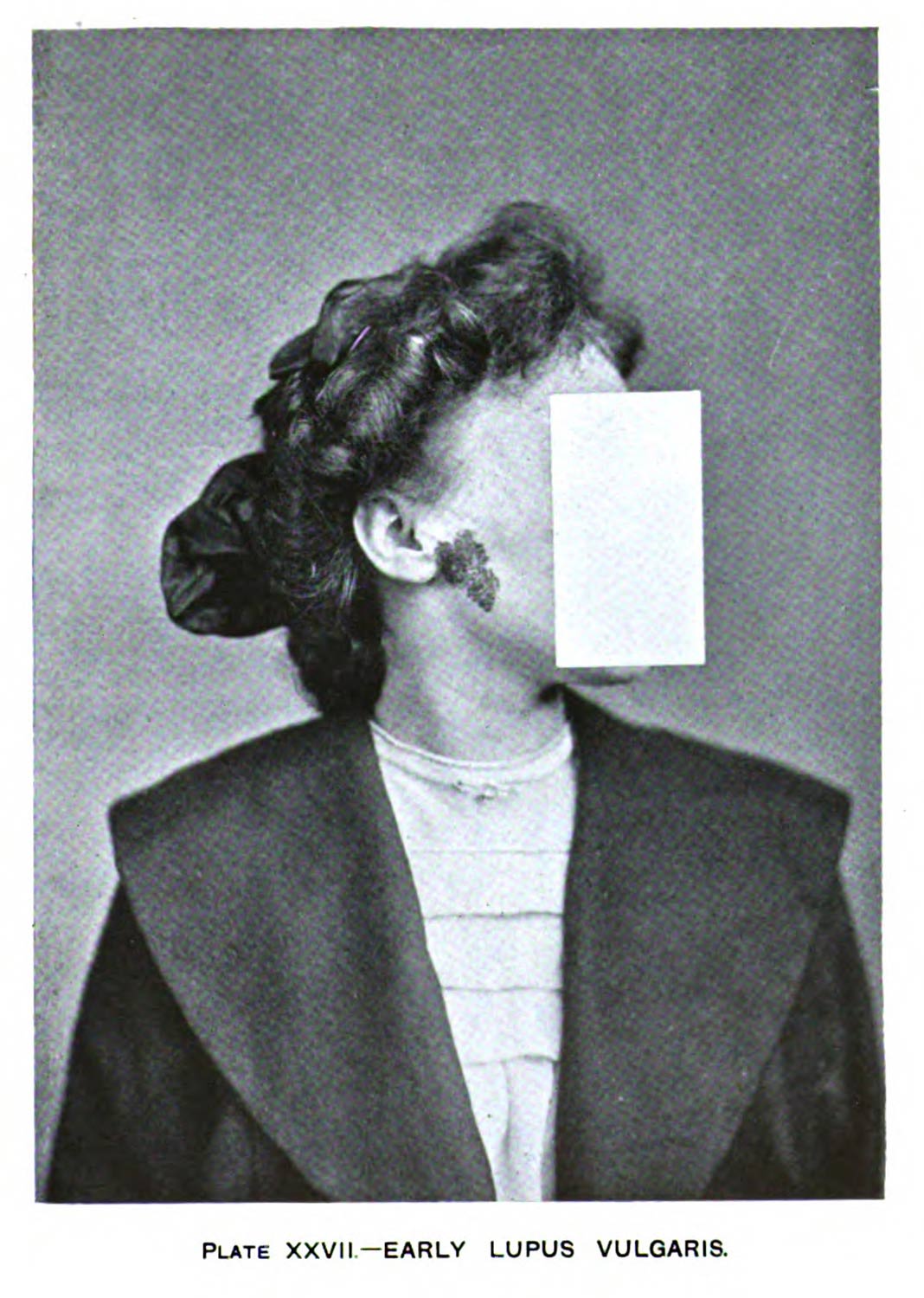

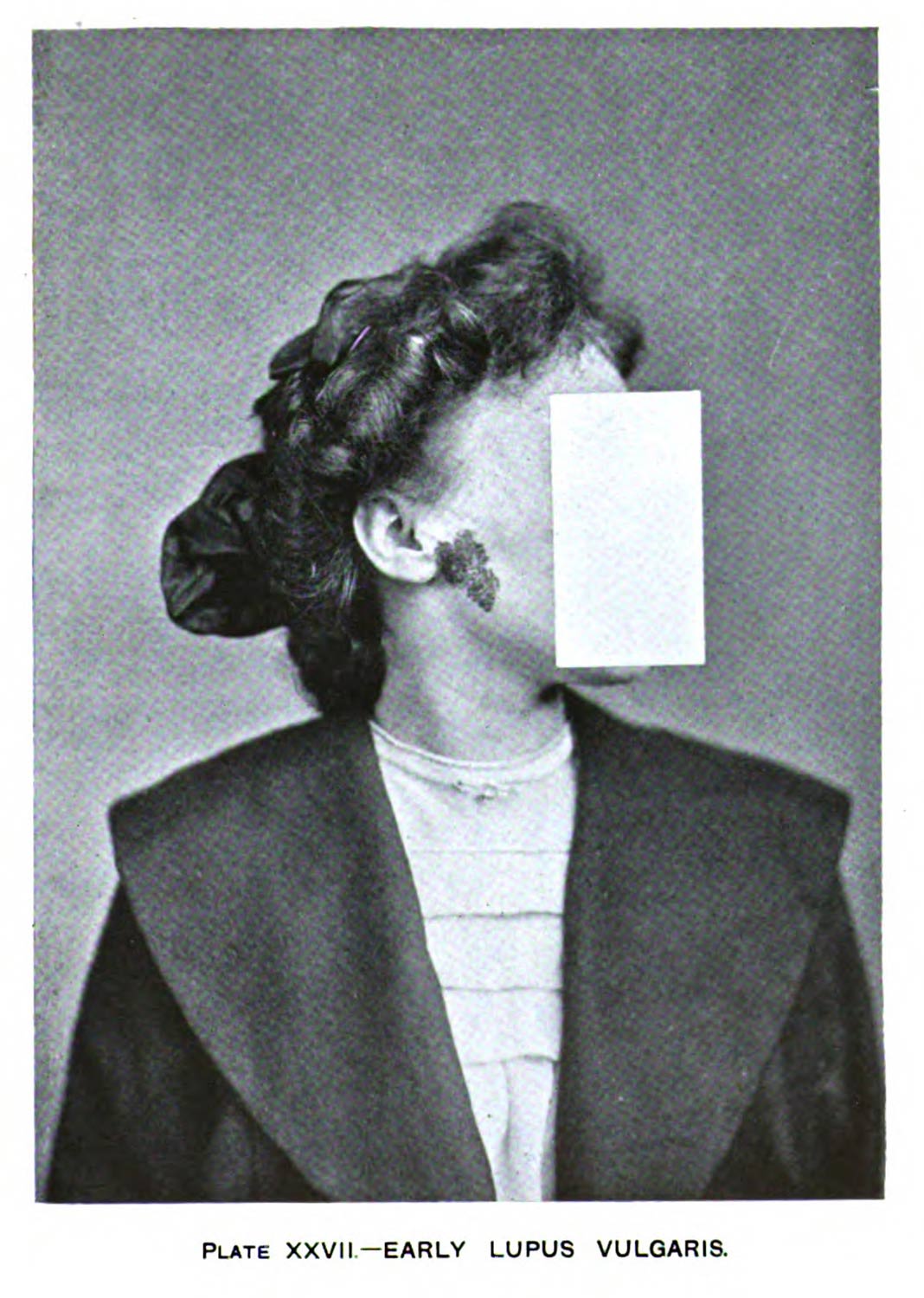

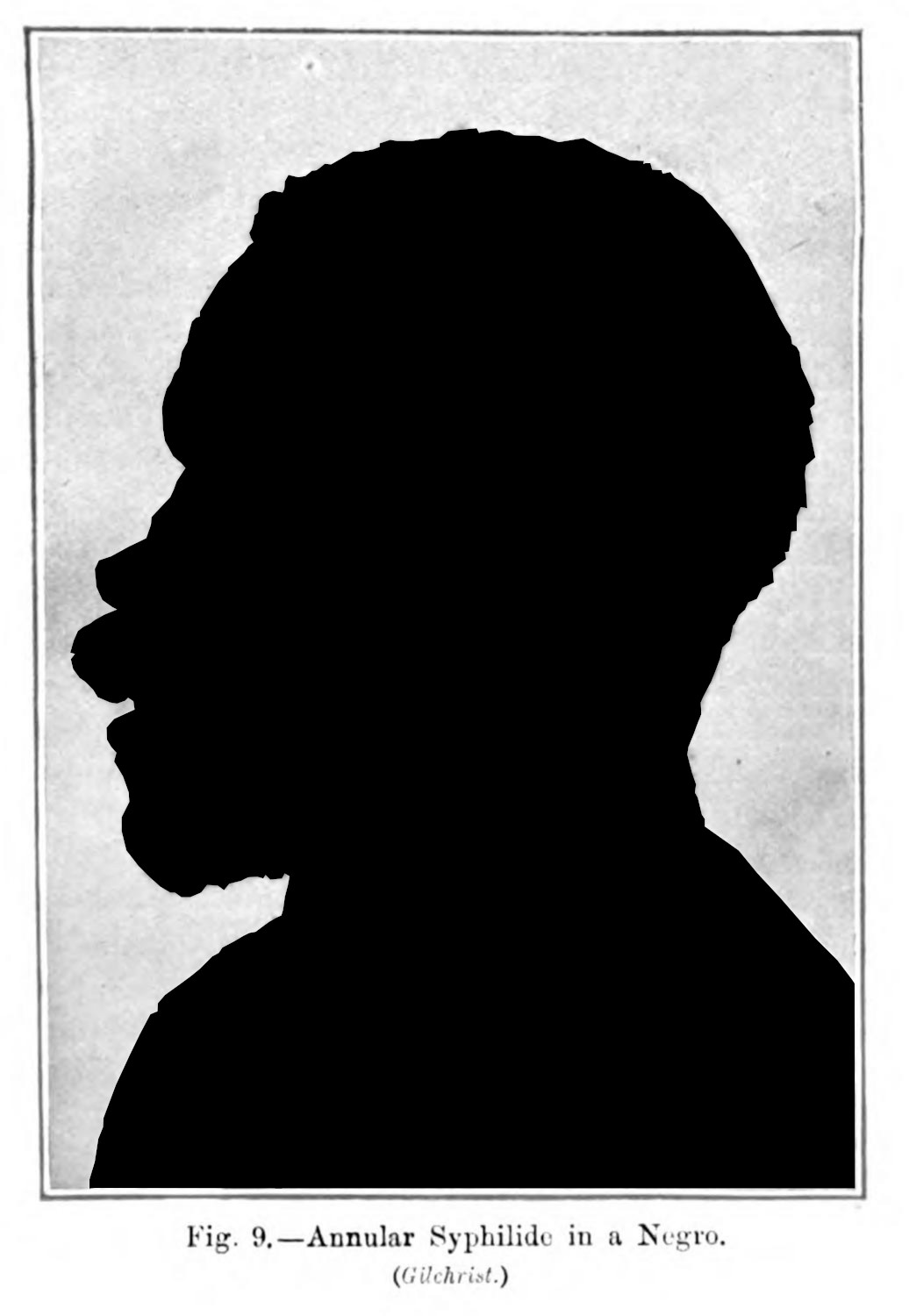

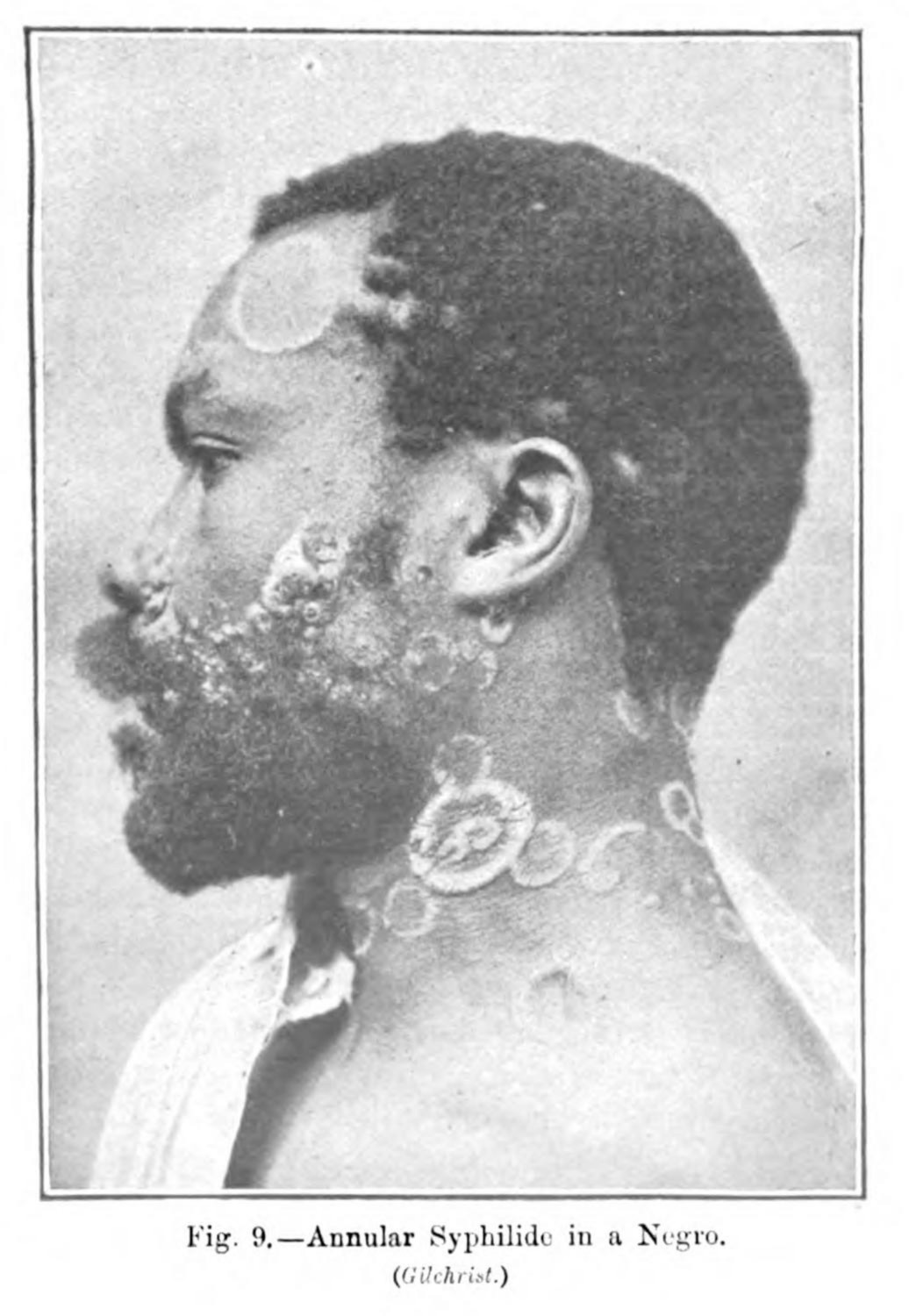

3.2.1 | 3.2.2 | 3.2.3 | 3.2.4 | 3.2.5 | 3.2.6Dermographic Opacities

3.3.1 | 3.3.2 | 3.3.3 | 3.3.4Tactical Pretensions

3.4.1 | 3.4.2 | 3.4.3Designing Opacity

A Shift towards the Anticolonial

4.1.1 | 4.1.2 | 4.1.3 | 4.1.4Refusals and Opacities

4.2.1 | 4.2.2 | 4.2.3 | 4.2.4Digital and Ethical Workflows

4.3.1 | 4.3.2 | 4.3.3 | 4.3.4 | 4.3.5Conclusion

4.4.1Coda

Prometheus Undone

5.1.1 | 5.1.2 | 5.1.3 | 5.1.4Appendix

The Tuberculosis Corpus

X.1.1 | X.1.2 | X.1.3Web Design

X.2.1 | X.2.2 | X.2.3 | X.2.4Installation Materials

X.3.1 | X.3.2 | X.3.3Index

Reflecting on the Terminal Imaginaries installation (3.2.1), I can concede multiple errors of scope. The production of this installation was driven by an interest to 1) learn more about medicine’s visual culture, 2) build on an interest in dermatology, 3) learn how to make a spatial video installation, and 4) to build in a public facing component. Some of these asks were framed by certain funding expectations,1 while others were personal desires.

I wanted to learn video art, in a desire to move away from my more traditional training in film and television production. In the five years following the completion of my MFA, I had become more and more disillusioned with the prospects of the cinema.2 Distancing myself from this medium entirely, however, felt too far a stretch,3 so I had moved to video art installation as a stepping stone to explore the spatial, non-theatrical engagements with moving images.

I wanted to use an art project to get a better sense of a prospective dissertation project, which I knew had something to do with medicine, but which lacked definition. As with many emerging scholars at the phase between their qualifying exams and the prospectus, I was still trying to define a specific research object.

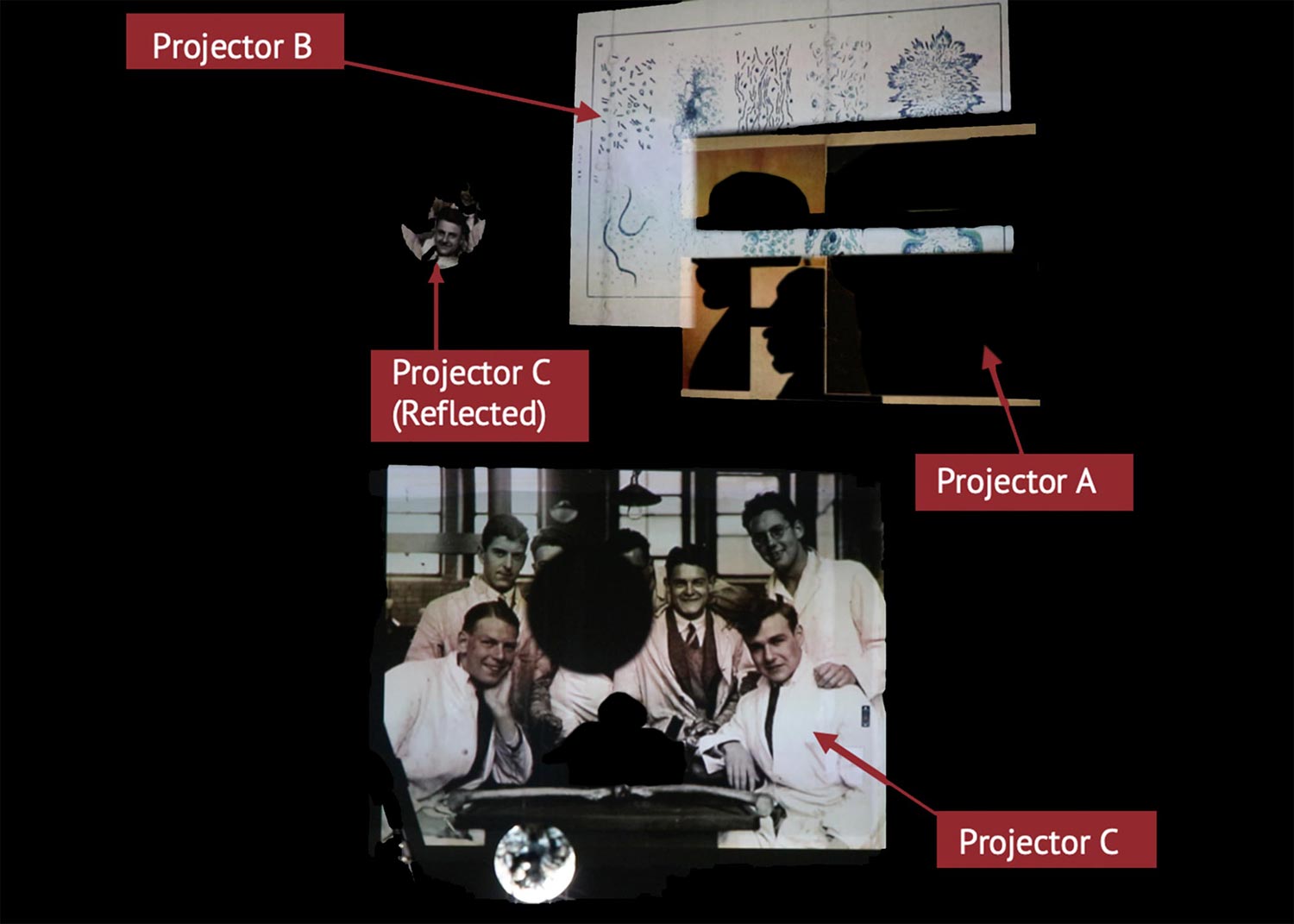

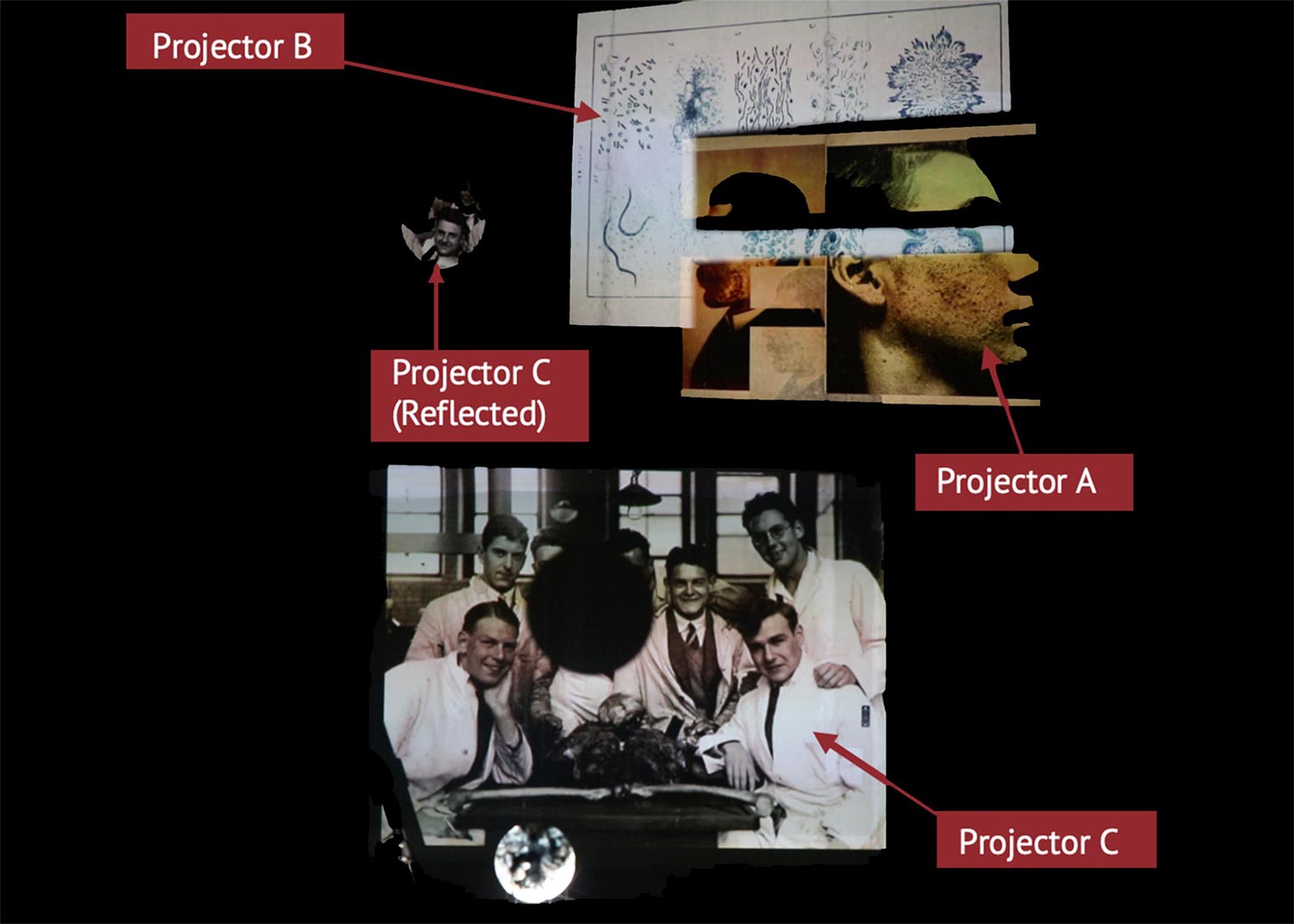

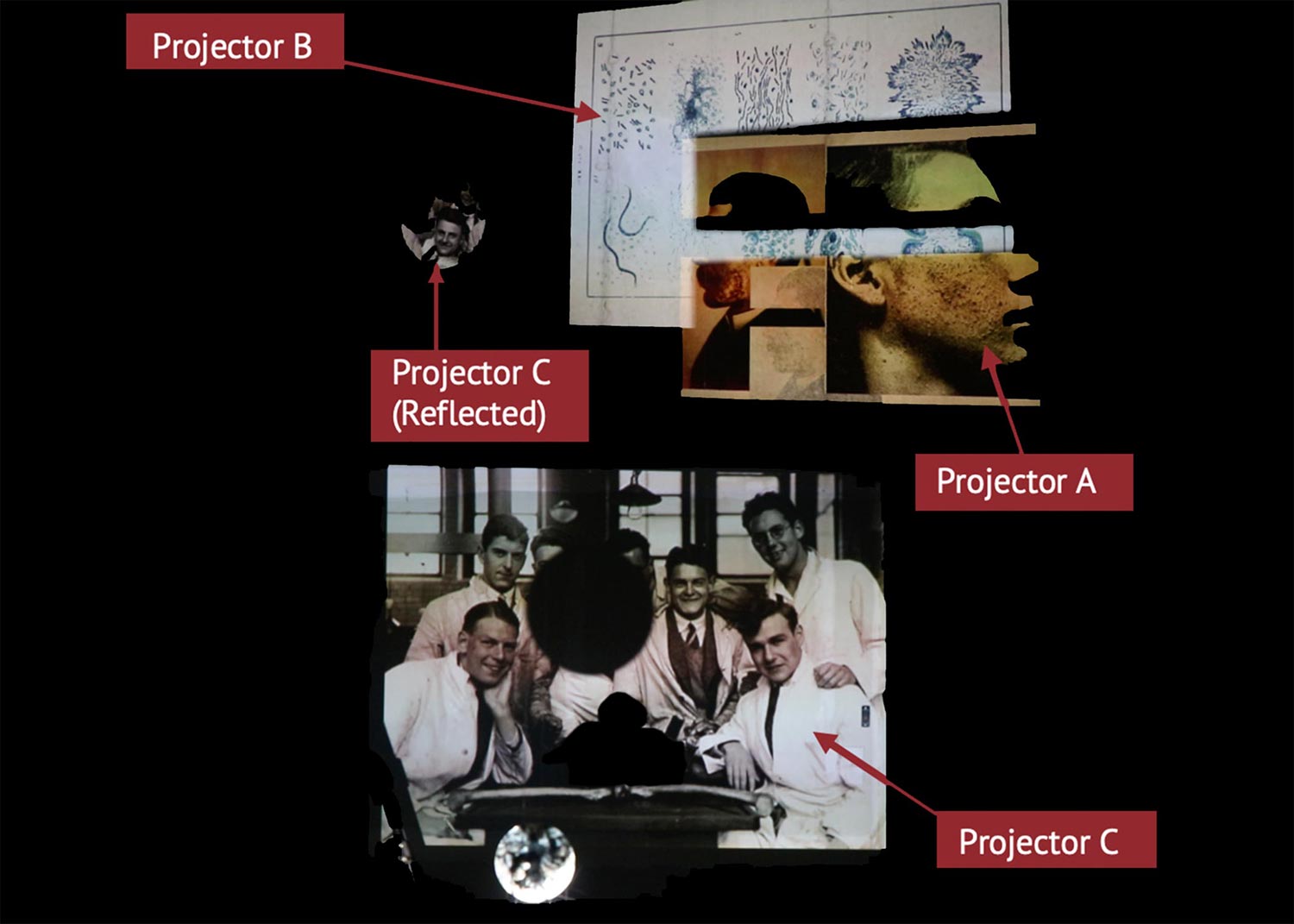

These scoping problems are common, especially for large-scale projects in and adjacent to the digital humanities.4 Terminal Imaginaries, while overtly broad, helped me narrow the project from one that addressed the entire field of medicine circa 1900 to a few specific interests, with each projector displaying a different kind of source material (fig. 1): one looked at anatomy, another looked at dermatology, and the last looked at doctor’s portraits. Each projector spoke to an interest, either explicitly stated on the project’s website, or found through reflection.

Projectors A and B overlapped, with Projector A drawing from dermatological atlases. I wrote, on the Terminal Imaginaries website,

The materials used for this installation were drawn from turn of the twentieth century medical textbooks, and they show a pre-Nuremberg visual logic concerning the anonymity of the sitter. But they also show the bodies from which medical knowledge was gleaned: from the bodies of the poor, the othered, and those who could not afford to say ‘no’ to a medical man.5

Projector B, looked at anatomical atlases. Again, from the website,

Projector B borrows images from Gray’s seminal anatomical atlas, and a few other textbooks from the period in contrast to the images found on Projector A. Where the clinical photograph indexes disease from and through the index of an instant in time, the anatomical image (while drawn from a specific subject) dislodges the index of its origin, affirming a means of seeing the human body abstractly. This process dehumanizes, and deindividualizes the matter from which it was pulled: the anatomical image loses its origin, and instead conveys a body that is perfect, whole and abstractly human.6

These two projectors overlapped, with the third projector (Projector C) casting the image on the opposite wall, and to where the audience would be funneled through:

Projector C is the only one that is pointed toward the audience: to illuminate the standing viewer, while also casting its image on the wall. Part of my desire was to imbricate those who come to see the installation: to have themselves be cast in the light of a history that they take for granted. It is a ground which has, in the century since, been capitalized upon again and again; a ground which I myself (a sick child at birth) would not exist without, but which maintains a certain relationship with the ill and their doctor.7

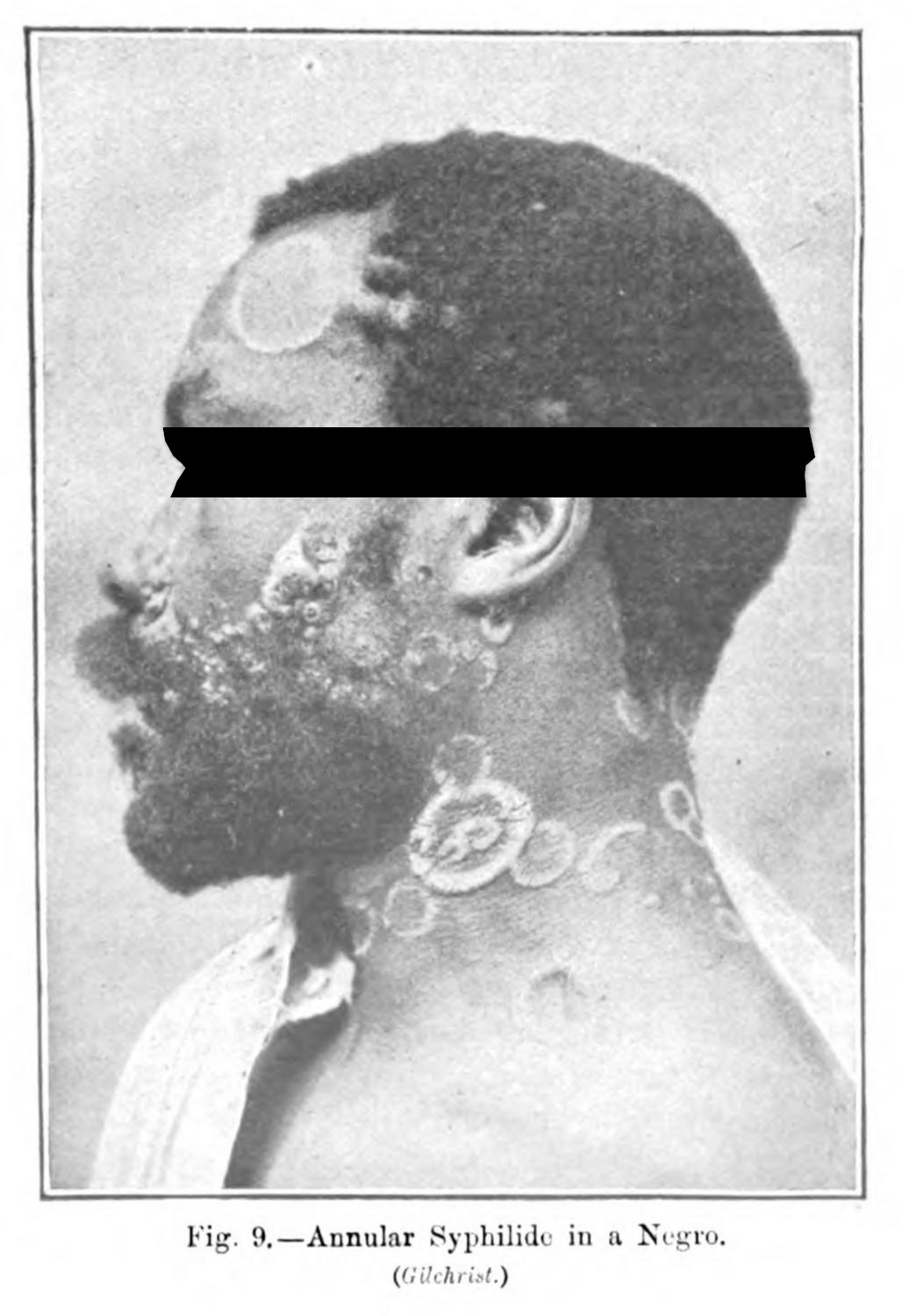

Overlapping projectors A and B (fig. 1) created an opportunity to think about the juxtaposition of the two image types. The kinds of dermatological images shown through projector A has a series of nested relationships with the anatomical, illustrative image of projector B. I had wanted to include some physical barriers between the projector and the screen, desiring a kind of physicality of the screen that seems so much a immaterial thing.8 What I realized, save for the mirror which cuts and recasts projector C, is that the physical implement did less to cut the light so much as order the space. Adding the black bar across the eyes of dermatological portraits (fig. 2) in the editing platform produced the desired effect without needing the finicky, too light, and poorly constructed flags.

I had begun to think about this erasure of the subject’s eyes in the way the unnamed narrator in Chris Marker’s Sans Soleil talked about censorship. In the English translation of the quasi-documentary-travelogue, the narrator argues, over images of Japanese television that edit out nudity, that, “[c]ensorship is not the mutilation of the show, it is the show. The code is the message. It points to the absolute by hiding it.”9 In the context of the film, the narrator, speaking through and about a semi-fictional filmmaker modelled after Marker, is thinking about the televisual image, and the ways it has its own kind of language.

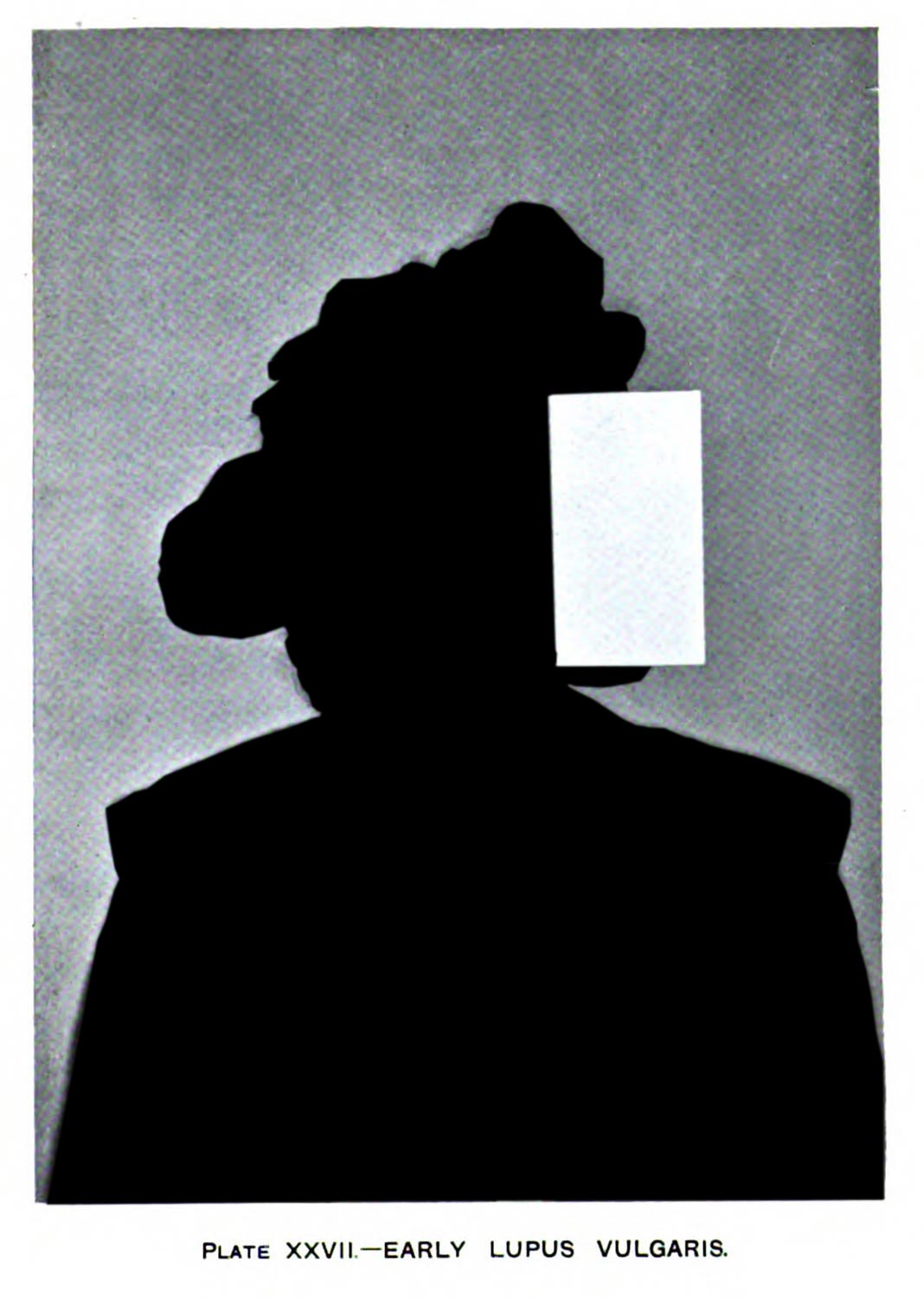

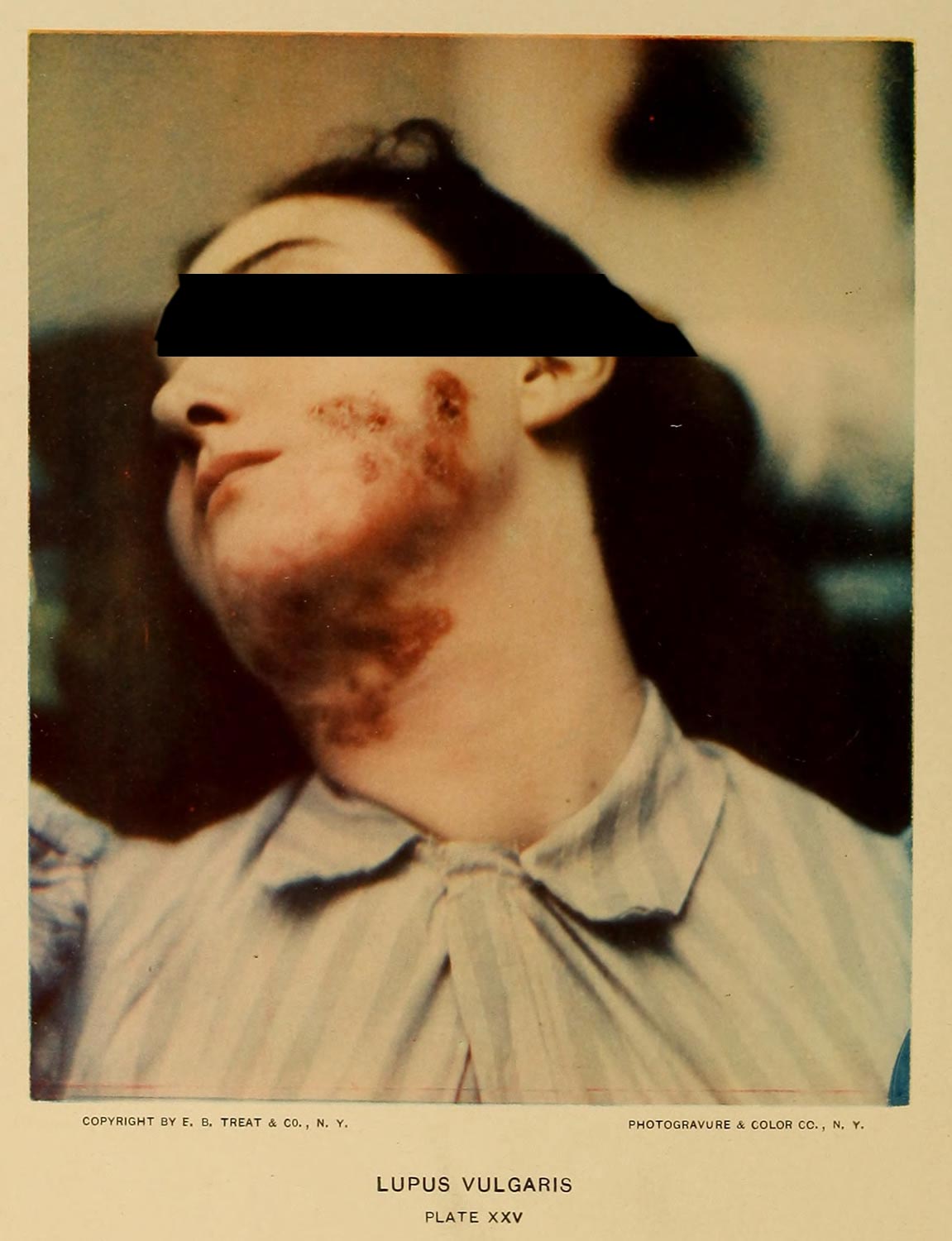

For my own work, I think this censorship as a critical praxis, a means to subvert the image through my intervention, drawing to focus on what made me so uncomfortable: the doctors never seemed to care as to the personhood of their subjects. When they did offer some anonymity, as with the woman with lupus vulgaris (fig. 3), it some how made my ethical concerns more concrete. Why give one subject the privilege of anonymity, when another seems so obviously disempowered by the clinician (figs. 3 - 5)?

In the three years since I completed Terminal Imaginaries, I have read work that complicates the assumptions I made. In some cases, patients may have had some agency about whether their bodies were put to film.10 As I will discuss in the next section (3.2.3), the project’s broad critique brings with it a set of problems which weakens the piece and the scholarship associated with it.

What is important is that in doing this project I began to think about how a concerted effort in the removal of data could be used as a means to point to and make explicit the systemic, aesthetic violence that permeates medicine’s research objects. In a moment of increasingly open data, in the egregious flush of access, conscious refusal is a critical praxis (2.4.3; 4.1.3; 4.2.3).11 The active engagement with the material and the willingness to transform that material in ways where it is less legible, became a method for this project and for the one that followed it. This enabled a way for me to think through the materials differently, and, in the context of exploratory research, afforded a specific kind of critique with which I continued to iterate.

These erasures point to the notion of opacity—or an ethics of refusal by a subject within western culture’s extractivist ideologies regarding the production of knowledge (3.3.1; 4.1.4)—which became the visual practice that guided “Dermographic Opacities” (3.3.1; 3.3.3)12 and this dissertation’s web platform (4.1.3; 4.2.4). It creates friction against dominant epistemic ideologies, and produces ways of understanding the past which an written or strictly academic analysis would have more difficulty describing.

-

Terminal Imaginaries was made possible through funding by Indiana University’s Institute for Digital Arts and Humanities and College Arts and Humanities Institute. As part of these grant applications, I was expected to produce something that interlinked arts practices and digital humanities practices. While I suspect that I did not have to do all of what I proposed, I felt obligated to try to fulfil these asks to the best of my ability. ↩

-

Scrambling as a wannabe filmmaker in Los Angeles, especially as one with an avant gardist streak like me, was something that seemed impossible when I graduated in 2016. The for profit cinema, so overbearing in the public consciousness of the city, felt like the only end, and one in which I could not and would not be able to flourish. ↩

-

This is, at least, considering my curriculum vitae, and the apocalyptic job market. ↩

-

One of my student academic appointments during the research for this dissertation was with the Institute for Digital Arts and Humanities (IDAH). My duties included assisting in consults with scholars interested in pursuing a project in the digital humanities. One of the main themes we saw with many of our consultees, was a misunderstanding of scope for digital projects, but also a need for further refinement of research questions. ↩

-

Purcell, Sean. “The Clinical Photograph.” Terminal Imaginaries Website (blog), 2021. https://terminalimaginaries.com/projector-a/

This site no longer exists. ↩

-

Purcell, Sean. “The Body Anatomized.” Terminal Imaginaries Website (blog), 2021. https://terminalimaginaries.com/projector-b/

This site no longer exists. ↩

-

Purcell, Sean. “The Anatomist’s Portrait.” Terminal Imaginaries Website (blog), 2021. https://terminalimaginaries.com/projector-c/

This site no longer exists. ↩

-

This claim is, perhaps, wrong. Scholars like Guiliana Bruno has interrogated the histories of media art and video art in ways that maintain and reinforce the materiality of the light—the film of the projected image.

Bruno, Giuliana. Surface: Matters of Aesthetics, Materiality, and Media. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016. ↩

-

Chris Marker. Sans Soleil, 1984. ↩

-

Rawling, Katherine D. B. “‘She Sits All Day in the Attitude Depicted in the Photo’: Photography and the Psychiatric Patient in the Late Nineteenth Century.” Medical Humanities 43, no. 2 (2017): 99–110. ↩

-

Christen, Kimberly. “Does Information Really Want to Be Free?: Indigenous Knowledge Systems and the Question of Openness.” International Journal of Communication 6 (2012): 2870–93; Christen, Kimberly. Gone Digital: Aboriginal Remix and the Cultural Commons.” International Journal of Cultural Property 12 (2005): 315–45. ↩

-

Purcell, Sean. “Dermographic Opacities.” Epoiesen, 2022. http://dx.doi.org/10.22215/epoiesen/2022.1. ↩