Introduction

Specimen Studies

0.1.1 | 0.1.2 | 0.1.3 | 0.1.4 | 0.1.5Methods

0.2.1 | 0.2.2The Structure of this Dissertation

0.3.1Tuberculosis' Visual Culture

Visual Practices in Medical Culture

1.1.1 | 1.1.2 | 1.1.3Seeing and Settling in the Sanatorium Movement

1.2.1 | 1.2.2 | 1.2.3 | 1.2.4 | 1.2.5Teaching Public Health

1.3.1 | 1.3.2 | 1.3.3 | 1.3.4 | 1.3.5Representing Doctors in Tuberculous Contexts

1.4.1 | 1.4.2Using Human Specimens in the Study of Tuberculosis

Seeing Disease in Methyl Violet

2.1.1 | 2.1.2 | 2.1.3 | 2.1.4Case Histories

2.2.1 | 2.2.2 | 2.2.3 | 2.2.4Visceral Processes

2.3.1 | 2.3.2Relation

2.4.1 | 2.4.2 | 2.4.3Arts-Based Inquiry

Introduction

3.1.1 | 3.1.2 | 3.1.3 | 3.1.4Terminal Imaginaries & Tuberculous Imaginaries

3.2.1 | 3.2.2 | 3.2.3 | 3.2.4 | 3.2.5 | 3.2.6Dermographic Opacities

3.3.1 | 3.3.2 | 3.3.3 | 3.3.4Tactical Pretensions

3.4.1 | 3.4.2 | 3.4.3Designing Opacity

A Shift towards the Anticolonial

4.1.1 | 4.1.2 | 4.1.3 | 4.1.4Refusals and Opacities

4.2.1 | 4.2.2 | 4.2.3 | 4.2.4Digital and Ethical Workflows

4.3.1 | 4.3.2 | 4.3.3 | 4.3.4 | 4.3.5Conclusion

4.4.1Coda

Prometheus Undone

5.1.1 | 5.1.2 | 5.1.3 | 5.1.4Appendix

The Tuberculosis Corpus

X.1.1 | X.1.2 | X.1.3Web Design

X.2.1 | X.2.2 | X.2.3 | X.2.4Installation Materials

X.3.1 | X.3.2 | X.3.3Index

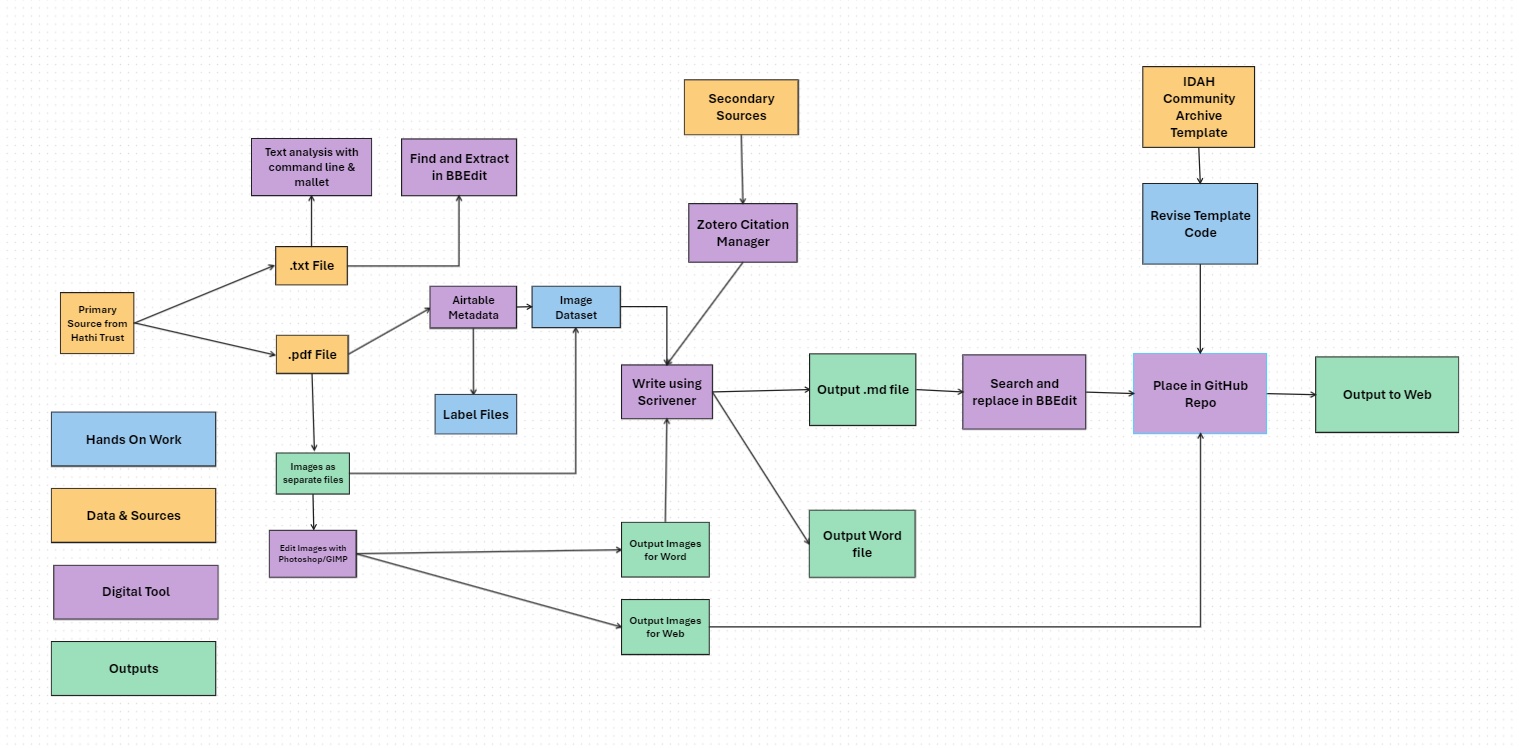

One of the problems that arises in publishing this dissertation on the Opaque Online Publishing Platform (OOPP) is that it required quite a bit of workflow management. For the text, I write it in Scrivener and export it into two file types: to Word (.docx), for review by the dissertation committee, and to markdown (.md), for it to be readable online. For images, I work from .pdf files, using an image editor—Adobe Photoshop or GIMP—to scale, crop, and alter them to be usable on the platform (4.3.3; 4.3.4) (table 1). This can be quite time consuming, and so for most of my drafts, I waited until the last possible moment to do the double export. This means that my committee has been asked to work with partial materials; however, given the scale of any dissertation project, this is to be expected no matter the medium.

What ends up happening in this process is a series of passes, not unlike drafting from an outline to a rough draft, to a finer draft, to a finished publication. While labor intensive, this kind of work affords another view of workflow: additional steps can be intentionally added based on the needs of the project. While I have spent many hours editing and prepping the images that have been used in this dissertation, I cannot do the same for my written words. I need to have the finished product before I can apply opacity to my semantic arguments. Because of this, the last edits to the markdown (.md) file are the addition of the “opaque-lines” and “partial-lines” span classes (X.2.1).

The text opacity filter is much simpler than the image one. I flag a line of text using the two different span classes, defined for partial opacity as

<span class=“partial-lines”></span>

and for full opacity as

<span class=“opaque-lines”></span>

These read as hypertext markup language (.html) span classes, which are compatible with markdown, and correspond with the associated cascading style sheet (.css) or sassy cascading style sheet (.scss) class.1 Any text that occurs between these classes will become crossed out for the partial class and blacked out for the fully opaque class, depending on which button is toggled. Importantly, these classes are often overlapping, as anything that would be opaque, would also necessarily be partially opaque.

The application of these final span classes to each markdown file provides an interesting tension which comes in at the end of every chapter: How much of my argument is going to be lost to the opacity filter? How will that argument change?

What I found, in doing this, is that my argument, and my understanding of the implicit exploitations which still inform this research project, continued to need to be addressed (4.2.5). Even at a medium-range—where I do not work with specific subjects, but instead a larger discourse—so much of my assumptions depended at least in some way on an extractivist position. For example, I found, when adding the opaque line span classes to the first chapter, that I needed to readdress my data set. Even though the chapter was about non-specimen images, most of my data practices depended on stolen, unethical materials to give context. In order to say that a percentage of the images in the data set (X.1.3) were of sanatoria, I needed to recognize that the other unseen part of that argument was dependent on exploitative practices.

I do not have an easy answer to this bigger problem about what to do about broad data-sets with some fraction of pilfered images, nor do I feel entirely comfortable in just publishing the work as is. In having to return to my own work, I am able to reflexively react to my own assumptions, and to try to alter and adjust my argument in a way that still affords a finished project, and which makes legible my unease with the project as a whole.

One of the reasons why I developed the OOPP was to have levels of opacity, as opposed to a single binarist switch, is that I wanted to encourage scholars to think about these refusals as being flexible: they can be applied based on the needs of the materials, project, and communities involved (4.2.3). Moreover, as evidenced in my own arts practices, I find the completion of a project to be a productive moment to reassess and reflect (3.2.4). I see the same recursive structure—of doing, reflecting, and doing differently—associated with practice-based research, as a potential method for finishing (3.2.3). Rather than being complete, there are still opportunities to reflect and reassess, without necessarily destroying the finished project. This latter notion is scaffolded on a practical concern: I cannot go back and redo this work. I do not have the time, or resources, or ability to reassess. Instead, this imperfect work can provide value for like-minded scholars as a tool, a foil, or a scaffolding for their own research.

What the opacity span classes afford, when added at this very late moment, is an ethics audit.2 This is a moment, before the publication of a project, where a researcher or team of researchers can look over their work and reassess the ethical position of their arguments. This reappraisal of their scholarship is not meant to negate it but, through a recursive tactic, acknowledge potential limitations within the project (4.1.3). The opacity function for this dissertation, especially with the written product, oscillates between an acknowledgement that certain discursive needs demand the inclusion of unethical materials—to which the opacity function works to flag and contest—as well as the limitations as a scholar to fully grasp the needs of an ethical position. Max Liboiron and their colleagues talk about this impossible footing in their community-based work, writing of the obligations (0.1.5; 2.1.4) which researchers bear:

Intervening in material processes in the world as feminist and anticolonial scientists means that we engender specific relations and thus specific obligations. These obligations come from where we are from, including our Métis, Kablunangajuk, local settler, and come-from-away settler positions. These obligations also come from our research, both as scientists and as STS scholars, as feminists and as anticolonialists. Yet as you may have anticipated, these obligations are sometimes at odds with one another. Thus, our obligations and relations are often compromised, meaning we are beholden to some over others, and reproduce problematic parts of dominant frameworks while reproducing good relations at other scales. Compromise is not a mistake or a failure—it is the condition for action in a diverse field of relations.3

What Liboiron and their colleagues are navigating are the various scales of violence that can be enacted while doing research: damage that can be done at the hyper local—the harm done to cod when killing it with a dull knife4—to the damage that is done at the regional, epistemic, or cultural level. The goal is never to ethically pure, so much as to be conscious to the various harms which research enacts, reflecting in such a manner as to not cause the same harms again.

My interest in this moment of reflection afforded in the ethics audit is that it helps better attune the work to the implicit functions of power in research. Power, here, refers to the all-encompassing definitional knowledge systems described by Michel Foucault:

The individual is no doubt the fictitious atom of an ‘ideological’ representation of society; but he is also a reality fabricated by this specific technology of power that I have called ‘discipline;. We must cease once and for all to describe the effects of power in negative terms: it ‘excludes’, it ‘represses’. it ‘censors’, it ‘abstracts’, it ‘masks’, it ‘conceals’. In fact, power produces; it produces reality; it produces domains of objects and rituals of truth.5

Foucault’s notions of power are not universal, nor intransigent; instead, they are historical, performed, and have potentials for change. What Foucauldian scholars tend to omit in their research is the fact that they too are articulating within a disciplining discipline, without fully reconceptualizing the very constructed boxes in which they inhabit and reproduce (3.1.1).6 An ethics audit encourages scholars to reflect on the kinds of arguments, objects, and assumptions which undergird their research, which may not be possible to change entirely ahead of publication, but which should be addressed in future projects. The ethics audit, then, is a moment of reflection to address the ethical limitations of the project’s discursive and epistemic order: to acknowledge limitations with the desire to continue to work.

-

The difference between these two is regarding the complexity of modern .css files.

Kalani Craig developed this functionality. ↩

-

Thanks to Kalani Craig for coming up with the specific term. ↩

-

Liboiron, Max, Emily Simmonds, Edward Allen, Emily Wells, Jessica Melvin, Alex Zahara, Charles Mather, and All Our Teachers. “Doing Ethics with Cod.” In Making & Doing: Activating STS through Knowledge Expression and Travel, edited by Gary Lee Downey and Teun Zuiderent-Jerak, 137–53. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2021. ↩

-

They use this example specifically, because this manner of killing the fish meant its death would be a prolonged, gruesome affair for both the researcher and the fish. ↩

-

Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. New York: Vintage Books, 1995. 194. ↩

-

Wynter, Sylvia. “Human Being as Noun? Or Being Human as Praxis? Toward the Autopoetic Turn/Overturn: A Manifesto” Slideshare (August 25, 2007). ↩